Articles

Syrian refuges in Turkey and the current security situation

Navvar Saban, Omran Center military expert and the Information Unit manager participated in a workshop on 20June 2019, about Syrian refuges in Turkey and the current security situation, which is the main reason behind the large number of refugees in Turkey. The workshop title was (The Integration of Syrian Refugees in Turkey) and was organized by (The German Marshall Funds of the United State (GMF) & the Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey (TEPAV)

Saban gave a brief introduction about the security and military situation in Syria in the beginning of his session, and went on to give a deeper clearer idea about:

1) Who are the Syrian refugees (ethnic, socioeconomic, and background)

2) Conditions forced them to leave Syria.

3) Problems they face in Turkey. Why they don’t want to go back.

4) Issues faced in regards integration

Hezbollah’s International Financing Operation: From Economic Resistance to Criminal Endeavor

Executive Summary

-

Hezbollah has been heavily reliant on Iran’s generosity, to fund its operation, with Tehran’s aid estimated at around USD 700 million in 2008.

-

The organization has nonetheless increasingly diversified its revenue base, getting involved in drug trade, counterfeiting operations, arms trade and money laundry operations, in the US, the Caribbean, Europe, and Africa.

-

Hezbollah has also been involved in licit ventures such as construction and various trading businesses in Africa.

-

In Lebanon and Israel, Hezbollah has mostly relied on dealing drugs to extort information from Israeli military or recruit new agents. However in recent years, more and more Hezbollah members has been involved in drug and other illicit trade scandals, as well as racketeering schemes, the organization having difficulty in cracking down on corruption.

Introduction

Originally, a southern Lebanese group focused on fighting the Israeli occupation (1982 to 2000), Hezbollah has morphed into a powerful paramilitary force with military activities throughout the Middle East region. Today, the Iran-backed militant group is firmly entrenched at all levels of the Lebanese political system including the government (the ministerial cabinet, i.e. majlis al wozara), the various state institutions, and the parliament. Hezbollah’s growing local and regional influence can be attributed to the astuteness of its leadership, its military prowess, and its substantial financial resources, including a yearly budget allocated by Iran.

The Israeli army estimated in 2018 that Hezbollah received between USD 700 million - 1 billion per year from Tehran.([1]) Sources within Hezbollah who spoke to the author added that the group has been diversifying its revenue stream through both licit and illicit funding. In recent years, drug and money laundering scandals have been linked to Hezbollah in South America, the United States, Europe, and Africa. In Lebanon, media reports and interviews with Hezbollah members have pointed to the involvement of figures in and close to the organization in drug and money laundering scheme scandals and in the grey economy.

Locally, much ambiguity surrounds the debate around Hezbollah’s involvement in the drug trade for several reasons including but not only because of widespread support the organization enjoys within its community. First, according to interviews conducted by the author in Lebanon, Hezbollah is mostly known to have directly dealt in drugs schemes with members of the Israeli military in exchange for information, also called “drug-for-intelligence”.([2]) Second, with the exception of a few situations, Hezbollah has been indirectly linked to illicit activity, via its supporters and donors. Another reason for the ambiguity is that in South America, radical Islamists whether affiliated with the Palestinian Jihad, Iran, and Hezbollah are often bundled together without clear distinction. Finally, Hezbollah members directly involved with illicit activity in Lebanon often use the coverage provided by their status in the organization to operate as free business agents, which highlights Hezbollah’s growing internal corruption.([3])

Taking all of these nuances into consideration, this paper will examine Hezbollah’s various revenue streams. In a first section, the paper looks into Hezbollah’s sprawling structure and its relationship with Iran. The second section will look at Hezbollah’s international illicit activity. The final section will focus on the organization’s illicit activity in Lebanon and Syria. This paper relied primarily on interviews conducted by the author with current and former Hezbollah members as well as experts and individuals close to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

-

Hezbollah’s Structure and Financial Relationship with Iran

In the late 1970’s, when southern Lebanon was engulfed in a war against Israel, a Shiite group known as The Amal Movement rose to power. The group, founded by Sayed Musa Sadr, supported the Palestinian struggle against Israel. In 1982, the organization split after its new leader Nabih Berry – now incumbent speaker of the Lebanese Parliament – decided not to fight Israel’s advance into Lebanon. This decision was contested by the Amal party’s Islamic branch, which defected as a result. The latter faction was trained by Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corp (IRGC) forces, which had been sent to Lebanon to stop the progress of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).([4]) With the support of Iran, a politico-military command structure bringing Islamists and former Amal cadres together and an ideological platform known as the ‘Manifesto of the Nine’ were forged for the nascent resistance, marking the foundation of Hezbollah.([5]) The platform called for jihad against Israel, emphasized Islam as the movement’s doctrine, and declared the signatories’ adherence to the Iranian wilayat al-faqih ideology.

Iran realized that in order to protect its military gains in Lebanon, it had to capture the hearts and minds of its proxy’s popular base. With Iran’s assistance, Hezbollah built an extensive network of social services in Lebanon.([6]) According to a report by the Middle East Policy Council (MEPC), Hezbollah developed a highly organized system of health and social service organizations under the umbrella of its Social Unit, Education Unit, and Islamic Health Unit. According to the MEPC, Hezbollah’s Social Unit includes four organizations: the Jihad Construction Foundation (Jihad al-Binaa), the Martyrs’ Foundation, the Foundation for the Wounded, and the Khomeini Support Committee. In the early 2000’s, the Jihad Construction Foundation delivered water to about 45 percent of the residents of Beirut's southern suburbs and led reconstruction efforts in the southern suburbs after the 2006 war with Israel. In an interview with the author, Annahar columnist and Hezbollah expert Brahim Beyram estimated that Iran provided Hezbollah with $200-300 million a year. However in 2017, the IDF assessed that Hezbollah was receiving around $830 million per year from Iran,([7]) with the expansion of the Lebanese Hezbollah operations into Syria, where over 7,000 fighters were at the time intermittently deployed. A figure that is believed to have dropped significantly with winding down of the conflict.

A source close to Hezbollah’s fighters told the author that “besides being financed by Iran, Hezbollah has diversified its money stream and is trying to be more autonomous financially.” This could explain growing accusations against Hezbollah about its involvement in illicit activities. According to Dr. David Asher, a senior fellow at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (FDD),([8]) Hezbollah’s drugs-for-intelligence program has evolved into a massive drugs-for-profit initiative. “Hezbollah, partnered with Latin American cartels and paramilitary partners, is now one of the largest exporters of narcotics from South and Central America to West Africa into Europe and is perhaps the world’s largest money laundering organization,” said Asher in a 2017 congressional testimony in front of the House Foreign Affairs Committee.([9])

-

Hezbollah’s International Illicit Activities

Hezbollah relies on a sprawling global network of members engaged in various illicit activities. Much of this effort is focused in Latin America. Hezbollah’s illicit activity in South America appears to be focused on two main areas. Through supporters within its popular Shiite base in keys areas such as the tri-border area (TBA) of Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina, as well as in Colombia and Venezuela. “Hezbollah’s drug trafficking operations in Latin America are spread over a number of places. The TBA is one; Colombia is another; there also important centers of trade that are used for money laundering purposes and smuggling, such as free trade zones there,” said Dr. Emanuele Ottolenghi, a senior fellow at FDD, working on the Iran program.([10]) In addition, Hezbollah’s activities have also expanded to other countries and regions such as the U.S. and Europe.

- The Tri-Border Area

In 2004, Assad Barakat was described by the U.S. Department of the Treasury as “one of the most prominent and influential members” of Hezbollah, according to a paper by Matt Levitt, an expert on terrorism and security at the Washington Institute For Near East policies.([11]) Barakat’s import-export store at the Galeria Page shopping center in Paraguay was reportedly used for various nefarious activities ranging from counterfeit currency operations to drug running. Levitt’s paper described the 2006 arrest of Farouk Omairi by the Brazilian Federal Police in Operation ‘Camel,’ for providing travel support to cocaine smugglers. Omairi was believed to be acting as regional coordinator for Hezbollah and was involved in trafficking narcotics between South America, Europe, and the Middle East.

Paraguay has reportedly arrested Moussa Ali Hamdan in 2010 for providing material support to Hezbollah by selling counterfeit goods, money, and passports.([12]) In 2013, Wassim Fadel was arrested in Ciudad del Este, Paraguay after he had used a 21-year-old Paraguayan girl as a “drug mule” to smuggle narcotics to Europe. The girl was caught with 1.1 kilos of cocaine in her stomach. According to a statement by Paraguayan police published by MEE, Fadel reportedly transferred the money he made from both narco-trafficking and the pirating of CDs and DVDs into bank accounts owned by people connected to Hezbollah located in Turkey and Syria. In May 2018, Foreign Policy reported that Paraguayan authorities raided Unique SA, a currency exchange house in Ciudad del Este, Paraguaya, and arrested its owner Nader Farhat for his role in an alleged $1.3 million drug money laundering scheme.([13]) “Farhat is alleged to be a member of the Business Affairs Component, the branch of Hezbollah’s External Security Organization in charge of running overseas illicit finance and drug trafficking operations,” said the article.

2. Venezuela

In 2008, the U.S. Department of Treasury sanctioned Hezbollah supporter Ghazi Nasr al-Din, a former Chargé d' Affaires at the Venezuelan Embassy in Damascus.([14]) Hezbollah maintained a friendly and close relationship with the Venezuelan government led by Hugo Chavez, which evolved “into a tight ideological and business partnership,” according to an article published by Now Lebanon.([15]) The same article, quoting Lebanese Hezbollah expert Kassem Kassir, underlined that “a number of students and young men went [to Venezuela] to participate in festivals, conferences and workshops. There were some consultants of Chavez who came to Beirut and visited Hezbollah officials.”

According to U.S. authorities, Venezuela acts as a safe heaven and a source of funding for Hezbollah members and supporters. In 2015, ABC International reported that Nasr al-Din maintained a close relationship with Tarek Aissami,([16]) former vice president of Venezuela who was accused by the U.S. of facilitating drug shipments out of Venezuela and of drug trafficking, and together they attended a meeting with members of the Cartel of the Suns, a powerful network of Venezuela traffickers. In 2009, Nasr al-Din was also linked to the transportation of 400 kilos of cocaine from Venezuela to Lebanon via Damascus, transported by Conviasa, the Venezuelan flag carrier.

“Spanish investigative journalist, Antonio Salas who covered extensively the subject, has emphasized that a group of Hezbollah members linked to the Nasr al-Dingroup have engaged in drug trafficking under protection of Aissami. These people enjoyed a special (privileged) relation with the state,” underlined expert Douglas Farah, in an interview with the author.([17])

3. Colombia

In 2008, U.S. and Colombian investigators dismantled an international cocaine smuggling and money laundering ring that allegedly used part of its profits to finance Hezbollah.([18]) At the heart of the case was a kingpin in Bogota, Colombia, named Chekry Harb, who went by the alias "Taliban." According to the LA Times, Harb's group paid Hezbollah 12 percent of its profits, much of it in cash. “Harb brags about his uncle in the court documents being a senior member of Hezbollah,” said Ottolonghi to the author.

In December 2011, U.S. authorities accused Lebanese drug kingpin Aymen Jomaa, operating out of Medellin, Colombia, of allegedly helping to smuggle large amounts of cocaine into the U.S. and laundering more than $250 million for the Mexican drug cartel Los Zetas.([19]) Aymen Jomaa worked with at least nine other people and 19 entities to smuggle cocaine out of Colombia, then launder the drug-related proceeds from Mexico, Europe, West Africa, and Colombia through a Lebanese bank. Sometimes part of that money was sent to Mexico City in cash shipments to be delivered to Los Zetas. The U.S. investigation also linked a money-laundering scheme to Elissa and Ayash Exchange,([20]) and to the Lebanese Canadian Bank, which were sanctioned under the USA Patriot Act 311. “The link between Aymen Jomaa and Hezbollah was made because the money was directly traced back to Hezbollah controlled accounts although Jomaa was known mostly to be a supporter of the militant group,” said Farah. “Jomaa laundered on average 200 million dollars a month for drug cartels. Based on a number of other cases, we know that Hezbollah facilitators take 15-20 percent share a year. That means that the Jomaa operation alone would generate more than 400 million a year alone for this organization,” said Ottolonghi in an interview with the author.

Investigators believe that some of the drug profits money was laundered through a used car trade-based scheme from the United States to West Africa. According to a report by the U.S. Department of the treasury,([21]) figures close to Hezbollah were believed to be involved with a drug merchandise and money laundering operation where products were transported across the Togo and Ghana borders on their way from Benin to the airport in Accra, and the cash was then shipped by Middle East Airlines to Lebanon. Hezbollah affiliates deposit bulk cash into the financial exchange houses with the money then routed through the Lebanese Canadian Bank and other financial institutions and subsequently wire transferred to the United States so the used-car businesses can purchase vehicles. The vehicles were then shipped to West Africa for resale, said the report.

4. The Caribbean

In 2009, 17 people were reportedly arrested in Curacao for alleged involvement in a drug trafficking ring with connections to Hezbollah.([22]) The police underlined that some of the proceeds, funneled through informal Middle Eastern banks, went toward supporting groups linked to Hezbollah in Lebanon. "We have been able to establish that this group has relations with international criminal organizations that have connections with the Hezbollah," prosecutor Ludmila Vicento said to the Guardian. The amount confiscated by the police was significant and included two shipments of cocaine totaling 2,000 kilograms (4,400 pounds). The traffickers used cargo ships and speedboats to import the drugs from Colombia and Venezuela for shipment to Africa and beyond to Europe, according to Curacao authorities.

5. The United States

According to a report by Matthew Levitt, in 2009 the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency revealed a series of Hezbollah criminal schemes in the U.S., which ranged from stolen laptops, passports, and gaming consoles to selling stolen and counterfeit currency, procuring weapons, and a wide range of other types of material support.([23]) “In those cases, senior Hezbollah officials from both the organization's public and covert branches played hands-on roles in the planning and execution of many of the criminal schemes,” said Levitt. In July 2015, Lebanese National Ali Hassan Mansour, was arrested pursuant to a provisional arrest warrant issued in the Southern District of Florida by French authorities through diplomatic channels.([24]) Mansour, a money launderer based in Beirut, was charged with multiple counts of money laundering over the course of a narcotics conspiracy. The report labeled Mansour as being a key money launderer and drug trafficker for Hezbollah’s External Security Office, and Business Affairs Component (BAC) global illicit network.

In 2017, another Lebanese man accused of trying to use his ties to Hezbollah to further a scheme to launder drug money pleaded guilty in New York.([25]) Joseph Asmar worked with Lebanese businesswoman Iman Kobeissi, who had boasted she could use her Hezbollah connections to provide security for drug shipments. Kobeissi, who had been arrested earlier, had admitted she had friends in Hezbollah who wanted to purchase cocaine, weapons, and ammunition, according to the complaint.([26]) Kobeissi said her associates in Africa could provide security for planeloads of cocaine heading to the U.S. and other countries. She was also accused by prosecutors of having laundered hundreds of thousands of dollars in illegal drug money through transactions in European and Lebanese banks. “The Iman Kobeissi case is one of the cases that have directly linked senior Hezbollah leadership to drug trafficking activities,” said Ottolenghi

6. Europe

In January 2016, ‘Operation Cedar’ raids targeted Hezbollah operations in France, Germany, Italy, and Belgium, led by local law enforcement and supported by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.([27]) These raids resulted in the arrest of over a dozen individuals involved in international criminal activities such as drug trafficking and drug proceed money laundering. During the raids, several millions in assets and cash were seized that were believed to be linked to drug proceeds that were collected by money launderers throughout Europe. ”These actions specifically targeted Lebanese Hezbollah criminal operations in Europe,” said Asher at the time.([28]) For Ottolenghi, Operation Cedar is another case that directly tied Hezbollah leadership to illegal activities.([29]) “Europe is a booming market for cocaine. Hezbollah taps that market by facilitating multi-ton shipments of cocaine from Latin America into Europe. Hezbollah operatives are involved in laundering its revenues there on behalf of local criminal syndicates,” he noted.

These prominent cases linked to Hezbollah’s illicit activity, and others not described here, demonstrate that networks linked to the Lebanese militant group were clearly operating at an international level. Project Cassandra, which was unveiled last year in 2017 by Politico magazine,([30]) was launched in 2008 by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to target Hezbollah’s illicit funding streams. The project showed that cocaine shipments – some traveling from Latin America to West Africa and on to Europe and the Middle East, and others through Venezuela and Mexico to the U.S. – were all connected to a line of dirty money, laundered through used car schemes that were shipped to Africa. The FBI believed at the time that the Hezbollah network was collecting $1 billion a year from drug and weapons trafficking, money laundering, and other criminal activities.

-

Hezbollah’s Legalized Financing

Hezbollah does not rely on illicit trade alone for financing, as the organization also has revenue from legitimate businesses in Lebanon and Africa. “Part of Hezbollah’s attempt to diversify its revenue stream is the organization’s licit enterprises. Hezbollah uses front figures to operate legitimate businesses mostly involved in construction, car dealing as well as gas stations in Lebanon, and trading activities in Africa,” said a source close to the party to the author.

In recent years, Hezbollah-linked businesses have been targeted by U.S. law enforcement organizations for money laundering activity. In 2018, the U.S. Treasury designated six individuals and seven entities pursuant to Executive Order (E.O.) 13224,([31]) which targets terrorists and those providing support to terrorists or acts of terrorism. Specifically, they designated Lebanon-based Jihad Muhammad Qansu, Ali Muhammad Qansu, Issam Ahmad Saad, and Nabil Mahmoud Assaf, and Iraq-based Abdul Latif Saad and Muhammad Badr-Al-Din for acting for or on behalf of Hezbollah member and financier Adham Tabaja or his company, Al-Inmaa Engineering and Contracting. The U.S. also designated Sierra Leone-based Blue Lagoon Group LTD and Kanso Fishing Agency Limited, Ghana-based Star Trade Ghana Limited, Liberia-based Dolphin Trading Company Limited (DTC), Sky Trade Company, and Golden Fish Liberia LTD, and Lebanon-based Golden Fish S.A.L. (Offshore) for being owned or controlled by Ali Muhammad Qansu. Adham Tabaja had already been previously sanctioned in 2015, along with Kassem Hijaj and Husein Ali Faoud.([32]) “The DEA has identified Adham Tabaja as one Hezbollah‘s most senior member within the organization’s Business Component Affairs,” said Ottolenghi. Tabaja is also known to be a majority owner of the Lebanon-based real estate development and construction firm Al-Inmaa Group for Tourism Works. The company’s subsidiaries include Al-Inmaa Engineering and Contracting, which operates in Lebanon and Iraq, as well as Lebanon-based Al-Inmaa for Entertainment and Leisure Projects. In 2018, Tabaja is believed to have used the Iraqi branches of Al-Inmaa Engineering and Contracting to obtain oil and construction development contracts in Iraq. Kassem Hijaj was also accused of investing in infrastructure that Hezbollah uses in both Lebanon and Iraq.

Another man, Husayn Ali Faour, was accused of being a member of Hezbollah’s Islamic Jihad, which is believed to be the unit responsible for carrying out the group’s overseas terrorist activities.([33]) Faour managed the Lebanon-based Car Care Center, a front company used to supply Hezbollah’s vehicle needs. Faour worked with Tabaja to secure and manage construction, oil, and other projects in Iraq for Al-Inmaa Engineering and Contracting. A new wave of sanctions in 2019, targeted Hassan Tabaja, the brother of Adham and Wael Bazzi for facilitating Hezbollah financial operations.([34])

A source close to Hezbollah members told the author that in addition to car, trading, and construction activity, the organization is also involved in the diamond and gold trade in Africa. The expert Douglas Farah concurs, adding that Africa was a good collection point for Hezbollah, whose activity ranges from blood diamond trade to Europe, especially to Antwerp, in Belgium.

Diamond and trade are not the only business Hezbollah members are involved in. In 2012, Reuters reported that the Democratic Republic of Congo had awarded forestry concessions to the Trans-M company, which was subject to sanctions by the U.S. for being a front company used by Hezbollah.([35]) Reuters explained that the concessions covered a 25-year lease for hundreds of thousands of hectares of rainforest in the central African country. “The concessions are capable of generating hundreds of millions of dollars in revenues over 25 years, if fully exploited,” forestry experts told Reuters. Trans-M was controlled by businessman Ahmed Tajideen, known to also be the owner of Congo Futur, a company that manages sawmills and is accused by the U.S. government of being a front for Hezbollah.

-

The Debate Around Hezbollah’s Criminal Enterprises and its Illicit Lebanese and Syrian Activities

Allegations of Hezbollah’s illicit activity schemes have been denounced by many Hezbollah members as well as by Lebanese experts privy to the organization’s internal workings. “Members of Hezbollah are known to be honorable and dedicated to the cause, this has made the success of the organization since its inception,” said Ahmad, a Hezbollah fighter who spoke to the author on the condition of anonymity. Despite the amount of attention they received in the press, several cases, such as that of Chekry Harb, are in many ways circumstantial. Harb was accused of cooperating with Hezbollah and having family relations with some of its members. A nephew of a Hezbollah operative, Harb donated large amounts to the organization. In the cases of Hamdan and Fadel there was little hard evidence of a clear link with Hezbollah. “While some people arrested in South America were directly linked to Hezbollah, many individuals involved in illicit activities are actually either sympathetic to Hezbollah or were intimidated by them into giving them donations,” said Farah. In addition, Farah underlines that in South America, no distinction is made between Iranian and Hezbollah operators, which adds to the general confusion.

Nonetheless, other cases such as Kobeissi, Farhat, Barakat, and Omairi, show a clear and direct connection between Hezbollah members and criminal entrepreneurs. In the above mentioned cases, even when the organization was not directly responsible for the illicit trade, it facilitated it and covered it. In addition, Hezbollah knowingly received money from shady business figures or drug dealers sympathetic to its cause.

For Annahar’s columnist and Hezbollah expert, Ibrahim Bayram, the U.S. accusations against Hezbollah and its supposed involvement in the drug trade are farfetched and political in nature. “There is a clear American agenda against Hezbollah and these drug trade allegations are there to support it,” said Bayram.([36])

However, at the local level in Lebanon, Hezbollah members appear to be directly involved in criminal enterprises including drug dealing, racketeering, production of counterfeited money and medication, both with or without the knowledge of the top leadership. “Hezbollah’s direct dealing with drugs is solely for political and security reasons. Most drug deals are connected to the drug-for-intelligence and information scheme it has run with members of the Israeli army,” said Hassan, a Hezbollah fighter who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Since its creation, Hezbollah has been using drug dealers, to pursue the organization’s intelligence and military objectives.([37]) Hezbollah was known to employ drug dealers for advancing its political interests, taking advantage of its control over Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, which is known for its lucrative poppy and hashish production to infiltrate the Israeli military. The organization gave drug dealers political protection as long as they provided the organization with information on Israel. Over the years, a number of Israeli military officers have been charged with drug smuggling or dealing from Lebanon and providing information to Hezbollah.([38]) Hezbollah has also relied on drug dealers to recruit agents among Israeli Arabs.

According to Hezbollah fighters interviewed by the author, Hezbollah’s involvement in the drug trade in Lebanon is no longer driven solely by political or military interests. Sources explain that today, some Hezbollah commanders are tapping into the lucrative drug market for their own personal benefit. This has happened as the organization’s clout has grown in recent years, with its consolidation of power in Lebanon in 2006, and its entry into the Syrian war in 2011. The author could not confirm or invalidate these allegations.

“Hezbollah turns a blind eye to the drug plantations around its training camps, and drug dealers provides it with significant contributions from their proceeds,” said a source close to the organization’s members, on the condition of anonymity. The Lebanese army has long been instructed not to approach spots where Hezbollah is known to host its training camps in the Bekaa, which is the hub of Lebanon’s drug production. One Hezbollah commander hailing from the Bekaa told the author that some members of the organization were involved in abetting dealers involved in the transfer of cocaine into Lebanon to be smuggled into Syria, an accusation the author could not confirm independently. According to a source involved in the drug trade, cocaine is smuggled into Lebanon where it is processed and sent to Syria, and from there to the Gulf.

Machines used in the production of the drug captagon are smuggled into Lebanon illegally via the port of Beirut where Hezbollah is influential. “Hezbollah commanders also facilitate through their control of Lebanese borders with Syria their export of drugs such as captagon,” added the Bekaa commander interviewed by the author and asked to remain anonymous. Lebanon is a large exporter of captagon, sent through the Beirut port or across the Syrian border, with the goal of reaching Gulf countries, explained a source close to the drug dealing networks on the condition of anonymity.

Hezbollah fighters, who spoke to the author for this report, accused the organization’s commanders of covering up illicit business dealings. “Hezbollah’s leadership is often aware of the dealings but has seem reluctant to reign on them because of the high military or political status many commanders have acquired within the organization, especially after the war against Israel in 2006 and currently in Syria,” complained one fighter. It is important to understand why Hezbollah is not doing anything about its members’ illicit activity and rampant corruption, because of its reliance on these commanders for its external operations.

In addition to the drug trade, members of Hezbollah are also involved in the production of counterfeited money in the Lebanese suburb of Dahieh, explained the Bekaa Hezbollah commander in an interview by the author. The counterfeit bills are in turn traded via an international network, which is why Lebanon is known to be a producer of counterfeited money. In 2016, the New York Post reported that a large money-counterfeiting ring was busted when a Lebanese man was arrested for allegedly selling hundreds of thousands of dollars in counterfeit U.S. currency to a global network of clients in Iran, Malaysia, and elsewhere.([39]) According to the Post, between 2012 and 2014, Louay Ibrahim Hussein and other members of the ring sold more than $620,000 in high-quality fake $100 bills and €150,000 in fake Euros to undercover agents. Hussein had allegedly claimed to undercover agents that he had access to as much as $800 million in high-quality counterfeit currency.

Other illicit dealings by Hezbollah members are connected to Iranian aid to Lebanon. One fighter also speaking on condition of anonymity explained that since 2006, food aid given by Iran to Hezbollah, often ended up being sold on the Lebanese market instead of being distributed free. In 2013, a warrant was issued against the brother of the Lebanese Minister of State for Administrative Reform, Mohammad Fneish Abdul Latif Fneish, in connection to a case of illegally imported medications.([40]) “The brother of another Hezbollah minister has also been accused of running a Captagon production facility in Dahieh, every one of us is aware of the issue,” said the Hezbollah commander hailing from the Bekaa and who spoke on condition of anonymity. The author could not independently confirm the accusations.

The Syria war has been another financial boon for Hezbollah commanders, said a Hezbollah fighter speaking on condition of anonymity to the author. “A lot of the weapons seized from Syrian ‘terrorists’ or from ISIS is not given to the Syrian army but sold on the black market ( in Lebanon), which has contributed for the decline of weapons prices such as Kalashnikov, PKC and B7 on the Lebanese market,” said a source close to Hezbollah fighters. The Syrian war has flooded the region with weapons being smuggled into the country. In 2016, a team of reporters from the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) and the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) uncovered discreet sale of more than €1 billion worth of weapons in the past four years to Middle Eastern countries that were known to ship arms to Syria.([41]) Thousands of assault rifles such as AK-47s, mortar shells, rocket launchers, anti-tank weapons, and heavy machine guns were being routed through an arms pipeline from the Balkans to the Arabian Peninsula and countries bordering Syria.

“There might have one or two accusations of corruption with the war in Syria but these are exceptional and individual cases linked to the conflict there. Hezbollah has very strict rules about anything seized in war theaters and even during battle we were forced to do a detailed inventory of what we seized, and we are obliged to report any mismanagement,” said one Hezbollah commander, commenting on Hezbollah’s alleged illicit activity.

Sources close to Hezbollah admit that its members have been promised lucrative infrastructure contracts in Syria, specifically in Homs and Aleppo. Sometimes, Hezbollah members sponsor Lebanese businessmen getting these contracts in return for a cut of the profits. “The same scenario is taking place in areas under Hezbollah control such as Dahieh. Hezbollah commanders are involved in the parallel economy of providing electricity, satellite connection and water, leaving the government with failing services,” said the source close to the fighters.

Conclusion

Despite the circumstantial nature of the evidence in some cases, Hezbollah’s involvement in large international criminal enterprises is difficult to dismiss. Reports and investigations all point to Hezbollah’s direct or indirect involvement in illicit activity at the international level. At the local level, the organization’s growing clout and the rampant climate of corruption prevailing in Lebanon have been conducive to the increasing involvement of Hezbollah-linked figures in illicit activity.

Although Western accusation of Hezbollah’s corruption and involvement in criminal activity do not appear to have much influence over the organization’s popular base of support, stronger sanctions are taking a toll, forcing the organization to try to make cuts in it budget or attempt to outsource some services to Lebanese government ministries. There are anecdotal reports of members of Hezbollah’s popular base complaining of cuts in aid to the families of martyrs and challenges faced by Hezbollah members in accessing the organization’s health services. With de-escalation agreement in effect in Syria, Hezbollah has been able to bring back a large number of its fighters, thus limiting its military expenditures. The organization’s members have also been slapped by a number of U.S. sanctions. “This nonetheless does not affect Hezbollah which does not resort to the official financial system,” said Bayram. However, sanctions have impacted Hezbollah’s capability to launder its money via front individuals and companies. A U.S. based financial consultant working on countering money laundering activities told the author that U.S. correspondent banks are forcing Lebanese banks to closely monitor and close accounts suspected of laundering money for Hezbollah, with dozens of accounts terminated as a result. A high-level source in a Lebanese public financial institution explained that the Lebanese Central Bank has applied strict measures to prevent Hezbollah’s use of the banking sector. “The use of Hezbollah in construction, car rental, luxury store as fronts is nonetheless a possibility,” says the official.

Besides the challenge posed by increased sanctions, Hezbollah is faced with a growing conundrum linked to corruption. The organization’s promise to focus on fighting corruption in the Bekaa Valley during the electoral campaign prior to the May parliamentary elections is an indirect admission of the poor state of affairs when it comes to governance issues and deep dissatisfaction of its popular base. Corruption among Hezbollah members is not the only grievance of Shiites, whose complaints focus more on Lebanon’s general state of affairs. Hezbollah previously claimed that it focused only on its resistance activities and Lebanon’s military defense, but with its participation in successive national governments since 2008, this argument no longer holds. Furthermore, deteriorating economic conditions are challenging Hezbollah, with sources within Hezbollah reporting a growing dissatisfaction due to severe pay cuts. It seems that financial sanctions, led to a decline in the organization’s revenues, coupled with increased corruption scandals and an extended truce period with Hezbollah’s nemesis Israel, could prove more detrimental to the group on the longer run.

([1])Top general sees increased Iran spending on foreign wars, Dan Williams, Reuters, January second 2018:

https://reut.rs/2XMMm63

([2]) Israel soldier among arrested 'Hezbollah spies, , BBC, 20 June 2010 , https://www.bbc.com/news/10462662

([3]) Interview with Hezbollah commander, by author, Dahieg, February 2018,

([4])Nicholas Blanford, Warriors of God: Hezbollah’s Thirty Year Struggle against Israel (2011).

([5]) Marc Devore, Exploring the Iran-Hezbollah Relationship: A Case Study of How State Sponsorship Affects Terrorist Group Decision-Making, Perspective on terrorism, Vol 6, No 4-5 (2012), http://www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/218/html

([6]) Shawn Teresa Flanigan, Mounah Abdel-Samad, Hezbollah's Social Jihad: Nonprofits as Resistance Organizations, volume 16 Middle East Policy Council.

([7]) Ahronheim Anna, Iran pays $830 million to Hezbollah, September 15 2017, Jerusalem Post , https://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Iran-News/Iran-pays-830-million-to-Hezbollah-505166

([8]) https://www.cnas.org/people/david-asher

([9]) Asher David, Attacking Hezbollah, financial networks , June 8 2017, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA00/20170608/106094/HHRG-115-FA00-Wstate-AsherD-20170608.PDF

([10]) Interview with Emanuel Ottolonghi by the author, June 2018.

([11]) Levitt Matt, Hezbollah narco-terrorism, September 2012, IHS Defense, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Levitt20120900_1.pdf and https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/js1720.aspx

([12]) Spetjens Peter, Paraguay: Is Israel's latest 'best friend' also a Hezbollah haven?, may 21 2018, Middle East Eye (MEE)

([13])Ottolonghi Emanuele, Lebanon is protecting Hezbollah’s cocaine trade in Latin America, June 15 2018, Foreign policy, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/06/15/lebanon-is-protecting-hezbollahs-cocaine-and-cash-trade-in-latin-america/

([14])Treasury Targets Hezbollah in Venezuela, June 2008, US Department of treasury, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/hp1036.aspx

([15]) https://now.mmedia.me/lb/en/reportsfeatures/how_much_does_venezuela_matter_to_hezbollah

([16])Blasco Emily, El FBI investiga la conexión entre el narcoestado venezolano y Hizbolá, January 31 2015, ABC, https://www.abc.es/internacional/20150130/abci-venezuela-droga-201501302321.html

([17]) Douglas Farah is a national security consultant and analyst, the president of IBI Consultants, and a Senior Fellow at the International Assessment and Strategy Center.

([18])Chris Kraul and Sebastian Rotella, Drug probe finds Hezbollah link, october 22 2008, LA ztimes, http://articles.latimes.com/2008/oct/22/world/fg-cocainering22

([19]) Longmire Sylvia, DEA Arrests Hezbollah Members For Allegedly Laundering Cartel Money, February 5 2016, Homeland Security https://inhomelandsecurity.com/dea-arrests-hezbollah-members-allegedly-laundering-cartel-money/ and https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/pages/tg1035.aspx

([20]) “Attacking Hezbollah’s financial network: policy options” June 8, 2017 statement of Derek S. Maltz, United States House of Representatives House Committee on Foreign Affairs.

([21]) Finding that the Lebanese Canadian Bank SAL is a Financial Institution of Primary Money Laundering Concern, Department of the Treasury, https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/LCBNoticeofFinding.pdf

([22]) https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/apr/29/curacao-caribbean-drug-ring-hezbollah

([23]) Levitt, Matt, Hezbollah's Criminal Networks: Useful Idiots, Henchmen, and Organized Criminal Facilitators, October 2016, National Defense University https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/hezbollahs-criminal-networks-useful-idiots-henchmen-and-organized-criminal

([24]) Asher Danid, Tracking Hezbollah’s Financial Network, June 8 2017, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA00/20170608/106094/HHRG-115-FA00-Wstate-AsherD-20170608.PDF

([25])Stemple Jonathan, U.S. says Hezbollah associate pleads guilty to money laundering conspiracy, June 27, 2017, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/usa-crime-hezbollah-asmar/u-s-says-hezbollah-associate-pleads-guilty-to-money-laundering-conspiracy-idUSL1N1IS1K2

([26]) Ya libnan, 2 Lebanese charged with laundering money for Hezbollah, October 10, 2015 http://yalibnan.com/2015/10/10/2-lebanese-charged-with-laundering-money-for-hezbollah/

([27]) Asher David, Tracking Hezbollah’s Financial Network, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA00/20170608/106094/HHRG-115-FA00-Wstate-AsherD-20170608.PDF

([28]) Asher David, Tracking Hezbollah’s Financial Network, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA00/20170608/106094/HHRG-115-FA00-Wstate-AsherD-20170608.PDF

([29]) Interview with Emaniel Ottolonghi, by the author June 2018

([30]) The secret backstory of how Obama let Hezbollah off the hook, December 2017, Politico, https://www.politico.com/interactives/2017/obama-hezbollah-drug-trafficking-investigation/

([31]) https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0278

([32]) Wilson Center, US sanctions target Businesses close to Hezbolllah, June 10, 2015 https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/us-sanctions-target-businesses-linked-to-hezbollah

([33]) Treasury Sanctions Hezbollah Front Companies and Facilitators in Lebanon And Iraq, Treasury Department, October 2015

([34]) US issues new Hezbollah-related sanctions, April 24 2019, Al-Jazeera, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/04/issues-hezbollah-related-sanctions-190424175927380.html

([35])Mahatani Dino, Exclusive: Congo under scrutiny over Hezbollah business links, March 16 2012, Reuters https://www.reuters.com/article/us-congo-democratic-hezbollah/exclusive-congo-under-scrutiny-over-hezbollah-business-links-idUSBRE82F0TT20120316

([36]) Interview with Brahim, Beyram, Beirut, March 2018.

([37]) Melman, Yossi, Hezbollah’s drug trail, October 72016, the Jersualem Post https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Analysis-Hezbollahs-drug-trail-469616

([38]) Israel soldier among arrested 'Hezbollah spies, June 2010, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/10462662

([39]) Eustaseuwich Lia, Lebanon man accused of selling counterfeited money abroad, July 26, 2016, New York Post, https://nypost.com/2016/07/26/lebanese-man-accused-of-selling-counterfeit-us-currency-abroad/

([40]) http://www.naharnet.com/stories/en/72039

([41]) https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/27/weapons-flowing-eastern-europe-middle-east-revealed-arms-trade-syria

Syria and Global Security Project

Omran Center for Strategic Studies launched the outcome of its research project, which began on 3 January 2018, entitled "Syria and Global Security", this project aimed to generate substantive knowledge on the positions and expectations of each party involved in Syria, in order to assess and develop avenues for peacemaking and post-war state building. This multilateral dialogue project is co-run by Omran Centre for Strategic Studies and the Geneva Centre for Security Policy . The workshops associated with the project offer a platform for experts and researchers to develop a common understanding of one another’s concerns and build the mutual trust that is necessary to resolve the crisis.

Discussion Papers

-

“Prospects of cooperation on restoring stability and institutional reform in Syria” Geneva, 21-22 September 2017

- "The emerging security dynamics and the political settlement in Syria", Syracuse, Italy, 18-19 October 2018

- Russian military police in Syria: function and prospects (EN)-Discussion Paper 1

- Russian military police in Syria: function and prospects (RU)-Discussion Paper 1

- Russian military police in Syria: function and prospects (AR)-Discussion Paper 1

- Iran in Syria: Decision-Making Actors, Interests and Priorities (EN) -Discussion Paper 2

- Iran in Syria: Decision-Making Actors, Interests and Priorities (RU)-Discussion Paper 2

- Iran in Syria: Decision-Making Actors, Interests and Priorities (AR)- Discussion Paper 2

- Isis and Nusra Funding and the Ending of the Syrian War (EN)- Discussion Paper 3

- Isis and Nusra Funding and the Ending of the Syrian War (AR)- Discussion Paper 3

- Reforming the Syrian Arab Army: Russia’s vision (EN) -Discussion Paper 4

- Reforming the Syrian Arab Army: Russia’s vision (AR) -Discussion Paper 4

- “The Politics and Modalities of Reconstruction in Syria”, Geneva, Switzerland, 7-8 February 2019

- Waiting for no one: prospects and consequences of bottom-up reconstruction in Syria (EN) -Discussion Paper 5

- Waiting for no one: prospects and consequences of bottom-up reconstruction in Syria (AR) -Discussion Paper 5

- Turkish experience with refugees returns to Syria (EN)- Discussion Paper 6

- Turkish experience with refugees returns to Syria (AR)- Discussion Paper 6

The Future of Syria: Towards Inclusive Peacebuilding

Today, Dr. Sinan Hatahet participated on the conference which was organizing by Chatham House to brings together policymakers, experts, academics and civil society leaders to identify the main institutional and Stabilization in Syria, and to offer policy recommendations in support of an inclusive peacebuilding process.

Commemorating 8 years of the Syrian revolution

In Washington 9 March, Dr.Ammar Kahf from Omran For Strategic Studies talked about the importance of nurturing independent civil societies at Syrian American Council's event on Commemorating 8 years of the Syrian revolution.

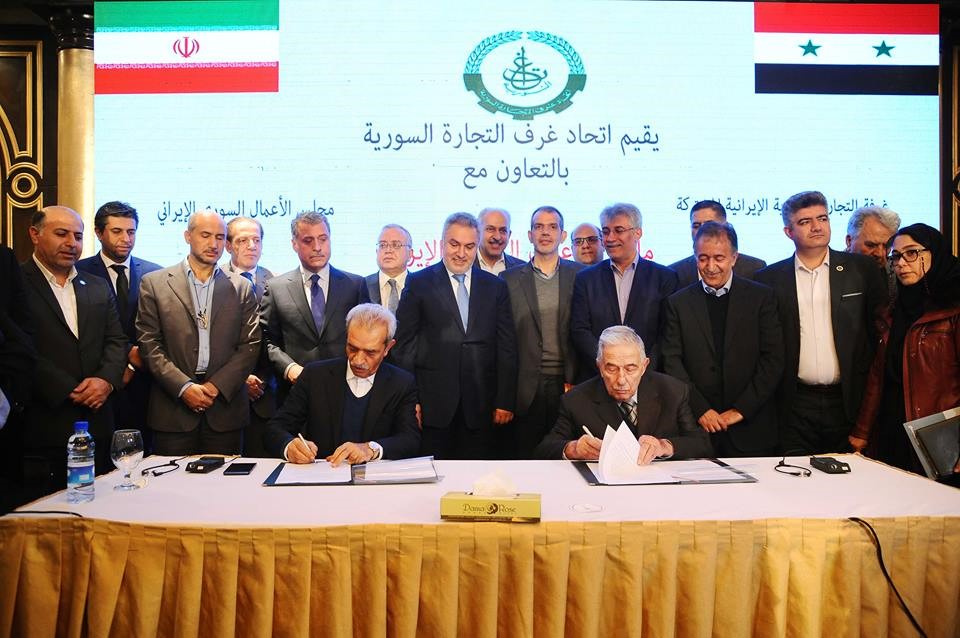

Official business visits between Iran and Syria 2019-18

Executive Summary

-

The Syrian-Iranian Business Forum opened in Damascus in January 2019. In attendance were Ishaq Jahangiri, the first vice president of the Islamic Republic of Iran, and Syrian Prime Minister Imad Khamis, as well as a broad swathe of businessmen and company representatives from both countries. This was the first official economic meeting between the two countries that took place in Syria in 2019.

-

In October 2018, a delegation of Syrian businessmen headed by Mohammad Hamsho, secretary-general of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce, traveled to Tehran. There they met with deputy minister of roads and construction for the Iranian cities of Akbar, Fakhri, and Kashan to discuss ways to expand cooperation between the private sectors in Syria and Iran in various economic, developmental, and industrial fields.

-

The 2018 delegation and the 2019 Business Forum events are the key pillars for the development of a stronger economic relationship between Iran and Syria.

-

An economic relationship between Iran and Syria did exist in previous years, but it was largely conducted quietly behind the scenes due to the challenging political and military conditions. With the improving conditions and the re-emergence of the Syrian-Iranian Business Forum, it has become easier for Iran to increase its economic role in Syria.

-

The Syrian-Iranian Business Forum is expected to play an influential role in Syria in 2019. Iran will increase its dependency on local Syrian brokers to do its business in the country so that its activities will not be detected and targeted by sanctions.

This report will provide a brief overview of the October 2018 and January 2019 economic visits between Syria and Iran and what resulted from them. Future reports will focus in greater depth on the Syrian-Iranian Business Forum activities in Syria in 2019.

The Re-emergence of the Syrian-Iranian Business Forum

In October 2018, a 50-person delegation of Syrian businesspersons and Parliament members visited Iran to participate in the Syrian-Iranian Business Forum. The delegation, which was headed by Mohamed Hamsho, Secretary General of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce, met with Iranian officials to discuss customs, investment, stock exchange, development projects, and free trade agreements.

This visit was the first of its kind since 2011. It happened after the Iranian ambassador to Damascus put significant pressure on the Syrian regime to stimulate economic relations and commercial trade between Syria and Iran, especially after the reopening of Syria’s southern Nasib border crossing with Jordan. Tehran wants to use Syria as a terminal to export Iranian goods to Arab markets through the Nasib crossing.

Iran also hopes to build relationships with prominent pro-regime Syrian merchants in order to establish business partnerships and apply for investment contracts. One example is the growing partnership between Iran and the businessman Mohamed Hamsho following the latter's purchase of the Sultan Company's share in the Syrian-Iranian automotive manufacturing company "Siamco.

The Syrian delegation to Tehran followed a number of preparatory visits by Iranian economic and political delegations to Damascus. It also followed a visit by the Syrian Minister of Electricity to Tehran, during which he announced the conclusion of various agreements related to the construction and maintenance of power plants in Latakia, Aleppo, and Deir Ezzor.

One of the most important outcomes of that visit to Tehran was the signing of an MOU between the Syrian delegation and the Tehran Chamber of Commerce for cooperation in various fields. The Syrian delegation also obtained initial approval from the Iranian side to reduce tariffs on 88 different Syrian exports from 4% to 0%.

| Position | State | Name |

| Secretary-general of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | Syria | Muhammad Hamsho |

| Member of Syrian parliament | Syria | Hussein Ragheb |

| Manager of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | Syria | Firas Jijkli |

| Businessman | Syria | Hassan Zaidou |

| Syrian Ambassador in Iran | Syria | Adnan Mahmoud |

| Member of Syrian Exporters Union | Syria | Iyad Muhammad |

| Member of Syrian parliament | Syria | Muhammad Kheir Suriol |

| Chairman of the Supreme Committee for Investors in the Free Zone | Syria | Fahd Darwish |

Syrian businessmen who attending the Syrian-Iranian business council meeting

Syria and Iran sign 11 agreements and memorandum of understanding

A number of Iranian officials and private sector representatives visited Damascus in January 2019 for the 14th session of the Syrian-Iranian High Joint Committee. Prior to this meeting, a number of Syrian officials and businesspersons had visited Tehran in preparation. The committee session in Damascus produced 11 signed agreements and memorandums of understanding (MOU) in various sectors:

-

Investment: An MOU for cooperation between the Syrian Investment Commission (SIC) and the Iranian Organization for Investment, Economic and Technical Assistance.

-

Transportation: An MOU between the General Establishment of Syrian Railways and the Iranian railways.

-

Economic: An agreement on long-term strategic economic cooperation.

-

Government: An MOU regarding the meetings of the High Joint Committee.

-

Trade: An MOU between the Syrian Ministry of Economy and Foreign Trade and the Iranian Ministry of Industry, Trade and Mine.

-

Construction: An MOU related to public works and construction.

-

Geomatics: An MOU between the Syrian General Organization for Remote Sensing and the Iranian National Geographical Organization.

-

Entertainment: An MOU for enhanced cooperation between the General Establishment for Cinema in Syria and Iran’s Cinema Organization.

-

Culture: An executive program for cultural cooperation was signed between the Syrian Ministry of Culture and the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance for the years 2019, 2020, and 2021.

-

Banking: An MOU regarding information exchange related to money laundering and terrorism financing was signed between the Syrian Anti-money Laundering and Counter-terrorist Financing Commission and the Iranian Money Transfer Unit.

-

Education: An executive program in the educational field was signed for the years 2019, 2020, and 2021.

Navvar Shaban | What can be achieved by the US Turkey joint patrols near Manbij

On the 09 th of November, Omran Dirasat military expert Navvar Shaban participated in TRT strait Talk show talking about:Turkey has stepped up its attacks on YPG targets in northern Syria, while also conducting joint patrols with the US in areas where the terror group operates.

Emerging Security Dynamics and the Political Settlement in Syria

Omran Center for Strategic Studies collaboration with The Syracusa International Institute, held a workshop on “Emerging Security Dynamics and the Political Settlement in Syria” in Syracusa, Italy, on 18-19 October.

The workshop brought together experts from UN, EU, France, Germany, Switzerland, US and many regional countries. The vibrant discussion tackled various issues including: future of the DMZ agreement in the north, the logic of the Iranian presence in Syria, the political economy of militias, and local security imperatives impact on peacebuilding.

This workshop is the one of many workshops hold under "The Syria and Global Security Project" who is co-run by Omran Center for Strategic Studies and Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP). It aims to offer a platform to build common ground and bridge the gap between the main stakeholders in the Syrian conflict.

Centralization and Decentralization in Syria: Concepts and Practices

Introduction

After seven years of conflict between the people and the Assad regime, Syria is now going through a difficult phase. The nature of the conflict has transformed whereby the role and effectiveness of local actors has been greatly maringalized compared to an increasing role for international state and non-state actors. The role of armed opposition factions has diminished as international military, administrative, and political influence has grown. These armed opposition actors are also in a phase of turmoil as they struggle to survive or integrate under direct international custodianship, after having previously received support from the Northern or Southern Operations Rooms. This process follows the series of meetings in Astana and Sochi, and after the political bodies were domesticated into official negotiating bodies that support the interests of countries with direct influence over them. At the same time, direct Russian influence came to dominate the political, military, economic, and administrative spheres. As a result, the concept of the unified framework of the "regime platform" versus the "opposition platform" in accordance with the Geneva II concept was discarded through the creation of several negotiating platforms on the sides of the opposition, the regime, and the Syria Democratic Forces (SDF).

At the same time as these political changes were happening, the areas of influence and control on the ground were consolidated in 2018 into the north and northwestern portion under Turkish control, the northeast under the U.S. and SDF control, and southwestern Syria under the influence of the U.S. and Jordan, allowing Israel to strike any sites that it deems threatening. The areas of siege and opposition group control have been eliminated. International and regional influence has thus become more distinct, as efforts to control and integrate both armed opposition and pro-government groups continue.

This new phase is characterized by a complex series of partial deals that build on one another, and the arrangements among the state actors are developing in a "step by step" policy approach. The "counter-terrorism" framework that was used to justify the entry of these countries into Syria, is no longer a justification for their continued presence and influence: the U.S. is increasingly focused on the "Iranian threat;" Turkey is focused on "fighting the PKK" and security its borders; Israel justifies its interventions with the need to protect its borders against the "Iranian threat" and to prevent the transfer of weapons and fighters toward its borders; and Jordan is now also interested in protecting itself against the “Shi’ite crescent".

In light of this new landscape, contributing writers to this book discuss several aspects of Syria's current form of governance and how experiences on the ground in the different areas of influence converge or diverge from the concepts of centralization and decentralization, both vertically and horizontally. Towards this end, the chapters of this book first clarify the concepts and forms of decentralization and the way they are applied in post-conflict countries. They highlight the important role that agreeing on the form of governance and power sharing is an important factor in maintaining territorial unity and in shepherding negotiations to a more relevant stage of the new post-conflict reality. Next, the authors delineate decentralization in terms of its political, security, financial, and developmental functions, and review the constitutional and legal foundations of administrative and political decentralization in Syria. Finally, the authors present the experiences and applications of governance since 2011 in the regime-controlled areas and opposition-controlled areas, as well as in the SDF-controlled in northeast areas of the Democratic Autonomous Administration. Woven throughout the book are comparative descriptions of the experiences from Iraq, Lebanon, and other countries emerging from conflict, to see what lessons can be learned from the ways that these countries have negotiated the distribution of powers between central and local administrative units.

This book aims to help lay out a path towards the restoration of the legitimacy lost by all parties in Syria through the organization of local governance tools based on the experience of local councils. Local councils have tended neither towards excessive forms of decentralization nor to authoritarian centralization, but have instead followed a path that strengthens local structures and sets limits to central state authorities by granting powers rather than delegating them. At this stage, it is essential to work in parallel on strengthening the central government while also safeguarding and reinforcing the gains of the local councils through constitutional guarantees and a new local governance law. This book also stems from recognition of the need to shift away from limited centralized negotiations among the two “sides of the conflict” through a constitutional process followed by general elections, towards a negotiation based on power-sharing arrangements. Local governing bodies and other local actors should be engaged in the process of deciding which functions and authorities are mandated to the central institution versus the local governing units.

The chapters of this book were contributed by several researchers who differ in their approaches, but they all agree on the need to develop a decentralized Syrian model that avoids the reductive binary approach of political decentralization / administrative decentralization or federalism, and one that is based on the sharing of powers and functions, thus transitioning Syria’s system of governance from local administration to local governance. There is no doubt that further development and discussion of these ideas is required, but we present this effort as a starting place for a dialogue in the Syrian community on the most authentic or locally developed form of governance for Syria, which after years of adhoc decentralization, has become more localized than ever before.

Finally, it is important to note that most chapters were written in late 2017 and early 2018, which was before the change of control of Damascus suburb, northern Homs and the southern front. The arguments for a tailored and customized Syria-centric decentralization model put forth are still valid regardless of the controlling armed party.

Executive Summary

Chapter one of the book focuses on the concept of decentralization and illustrates the differences among countries when it comes to choosing how they exercise administrative authority. Every country’s approach to governance is influenced by its political and social conditions, as well as the maturity and depth of its democratic practices. The need to shift towards a decentralized system becomes apparent after examining factors related to a state’s nature, size, and degree of political stability. Decentralization becomes a necessity for stability in some countries because of its core idea: the distribution of power and functions of state institutions between the central governments and local administrative units. This conceptualization reaffirms the fact that the transformation to fully decentralized system may be risky for many governments, despite the promise that decentralization holds as the solution for most conflicts in developing countries such as those in the Arab world. Chief among these problems is the need to expand the political and economic participation of citizens. Still, given the ethnic and sectarian diversity and complex nature of countries, decentralization can be a threat to state unity.

Chapter two describes political functions of the state in a decentralized system and how it is practiced in different versions of decentralization. Political functions of the state take many forms depending on the degree of decentralization and mode of local governance. The far end of a decentralized governance system continuum appears in the practice of full political decentralization (full federalism), where provinces and regions have their individual constitutions and laws, exercise special legislative, executive, and judicial powers, and influence federal government policy through a political oversight authority and through their representatives in the legislative branch councils. Local governments, meanwhile, exercise specific roles in these functions under the partial political decentralization within their constitutionally-vested authority. These roles are primarily related to domestic policy-making and the development of local rules and regulations that do not contradict federal legislations. In administrative decentralization modes of governance, the practice of political functions and duties is reduced to a great extent as it focusses exclusively on administrative and executive functions of local governing institutions. Local administrative units would then be fully subordinated and controlled by the central administration in the capital. In partial administrative decentralization modes of local governance, political functions completely disappear from local units.

According to chapter three of this book, the exercise of legislative and judicial functions within a decentralized system will require reforms in the Syrian judicial branch, such as: the restructuring of the Supreme Judicial Council to ban the executive branch from holding membership in it and stop its interference, and the repeal of laws that encroach on public rights and freedoms with judicial not executive branch oversight. Assessing the current form and content of the Syrian Constitution in terms of centralized or decentralized approaches highlights centralism as highly visible and grants authority to the presidency (which has broad constitutional powers) to override all other authorities and functions of the state. Instead, the principles of separation and distribution of powers should be applied to three independent bodies in order to create balance and cooperation between them. With regard to legislative duties in Syria, this paper shows that the Constitution has broadly granted legislative duties to the People's Council of Syria (Parliament) and the President of the Republic, transforming the mandate of the Parliament from drafting laws to ratification of presidential laws. Reforming this imbalanced structure requires redefining the scope and mandate of the Parliament, abolishing the broad powers granted to the President, and reducing the centrality of legislation process and parliament. There needs to be a shift toward some kind of decentralization that divides future legislative functions in a balanced approach between the exclusive jurisdiction of the legislative branch, and the jurisdiction of the executive branch for all that is not stated in text of the constitution.

The fourth chapter focuses on security functions in decentralized systems. In the context of conflict-ridden or post-conflict countries, it is critical and necessary to re-assess national security functions: their applications, mechanisms for implementation and governance, and how security roles are distributed at different levels of government. This paper emphasizes that the redistribution of security duties and authorities in decentralized countries (in accordance with the lessons from stable and unstable countries) may result in a more efficient and coherent security architecture depending on who and how such a process is executed and whether by means of national actors, cross boarder actors, or international actors. In the search for a governing framework of the Syrian security sector within a decentralized system, independent intelligence agencies should have a clear mandate of intelligence gathering only (except for police forces and anti terrorism units that can arrest citizens) and an identified geographical jurisdiction. Local governing bodies should be constitutionally mandated to provide local security services and conduct police functions and duties locally. The assessment and identification of security threats and risks and the counter strategy to such risks should be developed locally and shared with central agencies for coordination.

The fifth chapter highlights the dialectical relationship between decentralization and its role in local development in countries emerging from conflict. Local development is one of the most important determining factors in whether or not decentralization is adopted in these cases. While some of post-conflict countries have reached acceptable rates of economic and social development after moving to a decentralized system, others have not. This disparity may be due to factors linked to each country’s particular local development process and adopted form of decentralization. This paper emphasizes that in the context of the Syrian situation, the country has suffered from the absence of a clear developmental model for decades. This has led to major developmental imbalances at the central state level, which are most evident in the developmental disparities between Syrian governorates. The adoption of a model of administrative decentralization in Syria will help to mitigate this disparity by empower local communities to participate in the local development process.

The sixth chapter, which deals with financial decentralization, emphasizes the fact that the successful implementation of decentralized systems of government in post-conflict countries depends largely on their ability to establish regulatory frameworks for financial decentralization and mechanisms for the collection, distribution, and disbursement of financial resources at various levels of government and administration. Successful implementation also requires substantial reforms in fiscal policy in general and in spending policies in particular. This paper finds that that the model for allocating financial resources to the local administrative units out of the state budget in Syria has many flaws. It is necessary to grant administrative units greater financial independence and to define metrics for successful financial decentralization to measure whether these units are meeting developmental requirements and making effective contributions to economic and social stability in their regions.

The seventh chapter examines the reality of local administration in regime-controlled areas. It illustrates the dominance of the central government in the local administration systems in regime-controlled areas, the growing influence of the Baath party, and the increasing influence of local Iran-backed forces in the operations of some local administrative units. This paper finds that the service sector crises in the areas of local administration units are indicative of their lack of funding, dysfunctional mechanisms, and insufficient personnel, forcing them to rely on the central government to conduct their affairs. It also argues that the regime is not interested in decentralization – which runs counter to its desire to retain centralized control – but it does use decentralization politically as a bargaining chip for negotiations with the international community, particularly the Europeans. The regime also attempted to manipulate the boundaries of the electoral constituency of administrative units to change administrative districts and weaken opposition areas by preventing them from winning elections in their areas while rewarding loyalists.

The eighth chapter focuses on the reality of governance in Syrian opposition-controlled areas. It reaches several conclusions, the most important of which is that local councils have undergone changes in terms of structure, mechanisms of formation, and function, as their organizational structures have stabilized and they rely increasingly on the elections for their membership. They have also been able to consolidate their service roles, compared to their role in local security and politics. The financial file is one of the primary challenges facing local councils as they cope with growing financial deficits, due both to the nature of revenues and expenditures, and also their lack of financial systems or laws regulating their budgets. This chapter explains how the long duration of the conflict, the transformations in its nature, the push towards coexistence, and the survival of the regime have all stimulated competition between local actors, of which the local councils were one of the most prominent players due to their political value and local legitimacy. As a result of the way the local councils have dealt with these challenges and threats, they face one of three scenarios in the foreseeable future: vanishing entirely, forming regional or cross-regional self-administrations, or continuing the current independent local units structures.

The ninth chapter analyzes the reality of governance in the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. It shows that lack of transparency is a key feature of service delivery, financial administration, and the management of strategic resources within the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. The process of forming legislative councils (mandated to pass laws) in these areas was based on partisan consensus that relied primarily on the literature and system of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM). Laws passed by these legislative councils, such as laws related to self-defense, changes to school curricula, and civil status laws, are problematic. A review of the structure of the DAA and its legislative and executive bodies, shows the presence of a partisan political project that is being forced on the local population through its security and military apparatuses. This paper concludes that the DAA, though able to impose a unique governance model, still suffers from problems of representation, legitimacy within its population, and a lack of competent personnel, and it has failed to eliminate the local and regional concerns arising from this project.

The tenth and final chapter of this book proposes a unique Syria-customized decentralized framework, one that takes into account the importance of achieving stability. It highlights the importance of refocusing international negotiations on two parallel tracks: negotiations policies to strengthen central state institutions in order to create conditions for peace and stability, and empowering local governance models through local negotiations on power sharing of authorities and functions of the central state with local administrative units. They must also revisit the basic Geneva Communiqué according to the principle of power sharing agreements between the center and periphery and not only a central agreement where the opposition and regime share authority. This means prioritizing internationally-monitored elections over any other track, beginning with local administration elections.

In order to ensure the success of the elections, essential actions are required from the different parties with regards to the restoration of the functionality of police and local courts. It is therefore necessary to begin drafting a new law for local administration (decentralization) to allow locally-elected authorities to have full control over the work of the police and administration of local courts.

The opportunity exists for local councils to legitimize their structures and negotiate new authorities, guaranteeing a decentralized model that provides expanded authorities to the councils and governorates, based on the strength of their electoral legitimacy. This chapter emphasizes the need to empower the tools and foundations of local governance both constitutionally and legally, and to ensure that the countries with a presence on Syrian soil help push the negotiations to a peace-building stage and guarantee relative stability on the ground until an agreement on the various security arrangements is concluded.

for More Click Here: http://bit.ly/2B2Vxqd

Navvar Saban "Oliver": "There is no final agreement and no final disagreement"

Navvar Saban "Oliver", the Information Unit manager at Omran Center, recent interview entitled "Battle for Syria's last major rebel bastion on hold as Putin and Erdogan meet to discuss next moves" by Borzou Daragahi, published in the Independent

“There are 12 observation points were equipped with limited military equipment and their main role was to monitor the agreement done in Astana. at the moment when the regime started to mobilise its forces around Idlib, Turkey started to send reinforcements to some of these points.”

he also added the follwing , for the second week in a row, thousands of Syrians in the province took to the streets in peaceful, colourful demonstrations that recalled the first months of the 2011 uprising against the Assad family’s decades-long dictatorship. “For the time being, everything is postponed,” at the end he said. (There is no final agreement and no final disagreement.)

Independen: thttps://goo.gl/QxMjgt