Articles

Syrian Refugee Employment in Turkey

According to official statistics, the Turkish Republic hosts nearly 3.5 million Syrian refugees, more than any other country. A number of studies show that a vast majority of these refugees will remain in Turkey permanently, even if the situation in Syria becomes stable and return becomes a possibility. Despite this trend, however, government institutions and organizations have failed to establish a sustainable framework for integrating Syrian refugees into Turkish society. Although the Turkish government addresses some specific areas of need, many refugees must take responsibility for securing their own livelihoods. Due to a gradual decrease in international aid and the long-term presence of Syrians in Turkey, it has become more difficult for refugees to find suitable employment opportunities. Whereas issues of housing, education, health, and food are related to problems of capacity and bureaucracy, the issue of livelihoods is more closely linked to the legal framework and the perception of Syrian refugee employment among Turkish citizens. This problem is not only a humanitarian issue but a political one, both nationally and globally.

For Syrian refugees, employment is more than a job. It has a significant and sustainable impact on an individual’s life, future, and ability to integrate into a new society. Unemployment, however, is a significant problem in Turkey. Some estimates indicate that working-age people in Turkey account for more than 50 percent of the population, yet the unemployment rate exceeds 17 percent, according to the Livelihood Observatory. Moreover, in response to the influx of Syrian refugees in Turkey, an insufficient amount of funds has been allocated to livelihoods sector to enable Syrians to build their livelihoods in Turkey. According to the 2016-2017 plan of Syria's humanitarian response, the amount of funding available for the livelihoods sector was $11 million (USD), but the funding requirement was $92 million (USD). As a result, the Turkish government has faced significant challenges, creating employment opportunities for Syrian refugees, integrating and organizing refugees in the labor market, and addressing problems between refugees and their employers.

There are a number of obstacles that prevent Syrian refugees from developing their livelihoods. Most notably, legal procedures related to the employment of Syrian refugees lack clarity and integrity. In addition, there is poor communication between Syrian civil society organizations and the Turkish government, as well as a lack of representative bodies demanding employment rights for refugees.

Most Syrians live in Turkey under temporary protected status, which fails to ensure certain protections. In fact, Turkish labor laws that apply to Syrian refugees are inadequate and inefficient. Due to difficult financial conditions, refugees are vulnerable to exploitation, including unfair compensation. In addition, refugees performing physical labor at work face a higher risk of injury, yet some employers do not provide them with health or social insurance.

To overcome existing obstacles, all actors in the livelihoods sector should collaborate to create appropriate mechanisms that enable Syrian refugees to secure jobs and develop their livelihoods. Specifically, the Turkish government should create a database, accessible to all relevant parties, for Syrian employment opportunities and establish appropriate mechanisms to assess the qualifications of Syrian refugees. In addition, the government should implement vocational training programs for secured employment and establish a union for Syrian workers under the supervision of the Turkish Workers Syndicate. The government also should support Syrian refugee recruitment agencies and provide them with necessary funding and facilities. To support small business and micro-enterprisesfor Syrian refugees, government agencies should provide appropriate facilities. They also should facilitate banking and investment procedures for Syrians to expand their ventures and create new jobs, and they should utilize the financial resources and expertise of Syrians abroad in order to develop Syrian livelihoods in Turkey. In addition, the government should establish joint large-scale industrial projects connecting Syrian and Turkish investors.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) should identify and develop mechanisms to sustain livelihood programs and ensure their growth. They should establish a cooperative fund to provide small grants to entrepreneurs, and they should conduct community awareness and education campaigns to inform Syrian refugees about their rights and responsibilities in the labor market. In addition, NGOs should establish programs to help at-risk refugees find employment opportunities. They also should create sustainable initiatives that enable coordination and cooperation between Syrian and Turkish employers. These programs should produce joint economic projects in all sectors and support vocational training and rehabilitation programs for Syrian refugees. In addition, these programs should ensure that Syrian refugees are not exploited due to legal status or physical condition.

With the significant and lasting presence of Syrian refugees in Turkey, temporary solutions are no longer viable, especially as more and more refugees enter the labor market. Unless concerned parties in the Turkish government work to develop sustainable solutions, refugees and their host communities will face serious problems, such as increased tension between refugees and the local population, as well as social and economic instability. On the other hand, the employment of refugees will benefit the Turkish workforce and economy, while ensuring a promising future for Syrians in Turkey.

Workshop in Geneva:"Strategies for State Building in Syria"

Omran for Strategic Studies and Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP) hosted in Geneva a workshop entitled ‘Strategies for State Building in Syria,’ for a focus on centralisation and decentralisation formulas that fit post-war Syria. The workshop is part of the Syria and Global Security Project, jointly run by the GCSP and Omran. The project aims to offer a platform for collective informed discussions on Syria that could build bridges between experts and researchers in order to bring peace and security to Syria and the region.

The workshop brought together 21 experts and researchers from Germany, Norway, Russia, Syria, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States. The participants gathered for two days on 1-2 February, 2018 to exchange views on potential trajectories of state building in Syria. The workshop discussed the geo-strategic context for political reform, as well as, political, administrative, financial and security aspects of centralisation and decentralisation.

For more details, a report on the workshop is planned to be published soon on this website.

Meeting entitled “Local Councils and Security Sector Reform in Syria”

The representatives of various public institutions and diplomats serving in the Embassies in Ankara attended the meeting as well as OMRAN and ORSAM representatives. Two reports prepared by OMRAN Center experts with respect to the local councils and security sector in Syria were presented at the meeting.

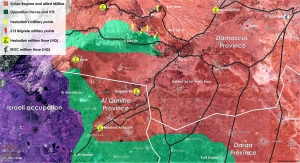

Territorial Control Map - Qunitra - 21 Dec. 2017

Iran has continued its attempts to expand in southern Syria despite international agreements aimed at curbing its role in the area. Russian and American the influential countries in southern Syria consider the arrival of Iranian militias to the Jordanian-Syrian border and the border of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights to be “a red line,” which has necessitated direct interventions. Despite this, Iran has continued its expansion as part of the encirclement, which it has pursued in recent months.

Quneitra Front and Western Ghouta Battle Timeline (November – December)

- November 3, Regime Forces and Hezbollah repelled a large attack of HTS, in "Hadr" city in the northern side of the Golan Heights.

- 17 November, Israeli tank attacks Hezbollah “Qars Nafal” position between "Hadr" & "Ain Teenah" position, in the western side of Quneitra.

- 23 November, Hezbollah takes control of South "Beit Tima" after taking control of "Halef shor" and "Tell Al Teen."

- 30 November, Hezbollah and Regime forces established full control over the strategic hills of "Taloul Barda’yah" near the occupied Golan Heights.

- 10 December, Hezbollah and Regime forces have secured their recent gains in the Beit Jinn pocket in southern Syria.

- 13 December, According to pro-regime Medias, Regime forces, and allies will continue their operations in the area until they liberate the entire pocket or local militants accept a withdrawal agreement to Idlib.

- 17 December, Members (HTS) have reportedly started withdrawing from the village of "Maghr Al Meer" to the town of "Beit Jinn" in southern Syria.

- 19 December, According to pro-regime sources, Regime Forces, and Allies reached the eastern entrance to the village of "Maghar Al Meer." However, they were not able to enter the village because they failed to capture the nearby height – Tal Marwan (Marwan Hill).

Brigade 313 "IRGC New Military Formation"

In November 2017, Daraa province has witnessed surprising competition between Iran and Regime forces around the conscription of Syrian young men from the province, as well as the formation of a new force, Brigade 313, which is under the authority of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.

Despite the Iranian-led brigade only being around for a number of months, it has attracted more than 200 young men; members who were conscripted for the formation were young men from Daraa who were known to work on behalf of the regime, who were currently promoting the force based on its benefits, and the salary, which its members received.

Enlistment takes place at the Brigade 313 headquarters in the city of Sa'Sa', and new members receive an ID, which has the logo of the Revolutionary Guard, ensuring his ability to pass through Regime forces checkpoints.

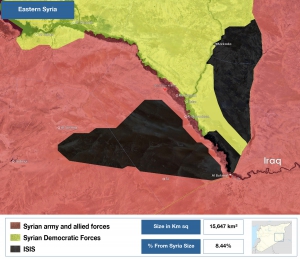

Why Reports of ISIS’ Demise Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

During the same week the U.S. and Russia declared victory over ISIS in Syria, the militant group launched a series of surprise attacks around the country. Despite the triumphant claims of world leaders, these offensives suggest such statements are a little premature.

The same day that President Vladimir Putin declared victory over the so-called Islamic State, the militant group launched a surprise offensive against government forces in Deir Ezzor province, killing up to 31 pro-government fighters in the following three days.

“In just over two years, Russia’s armed forces and the Syrian army have defeated the most battle-hardened group of international terrorists,” Putin told Russian forces on Monday during a visit to Russia’s Hmeimim air base in Syria, before ISIS attacked government positions north of the town of Boukamal, a former key stronghold for the militants.

U.S. President Donald Trump made similar victory claims on Tuesday while signing the National Defense Authorization Act into law. The bill, he said, “authorizes funding for our continued campaign to obliterate ISIS. We’ve won in Syria … but they [ISIS] spread to other areas and we’re getting them as fast as they spread.”

The following day, however, ISIS militants engaged in clashes with a Pentagon-backed rebel group near a U.S. base in al-Tanf in southwest Syria. Militants near the Palestinian Yarmouk camp south of Damascus also launched an attack on government positions in the nearby al-Tadamon neighborhood, seizing 12 buildings. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights described it as the largest offensive south of the capital “in months.”

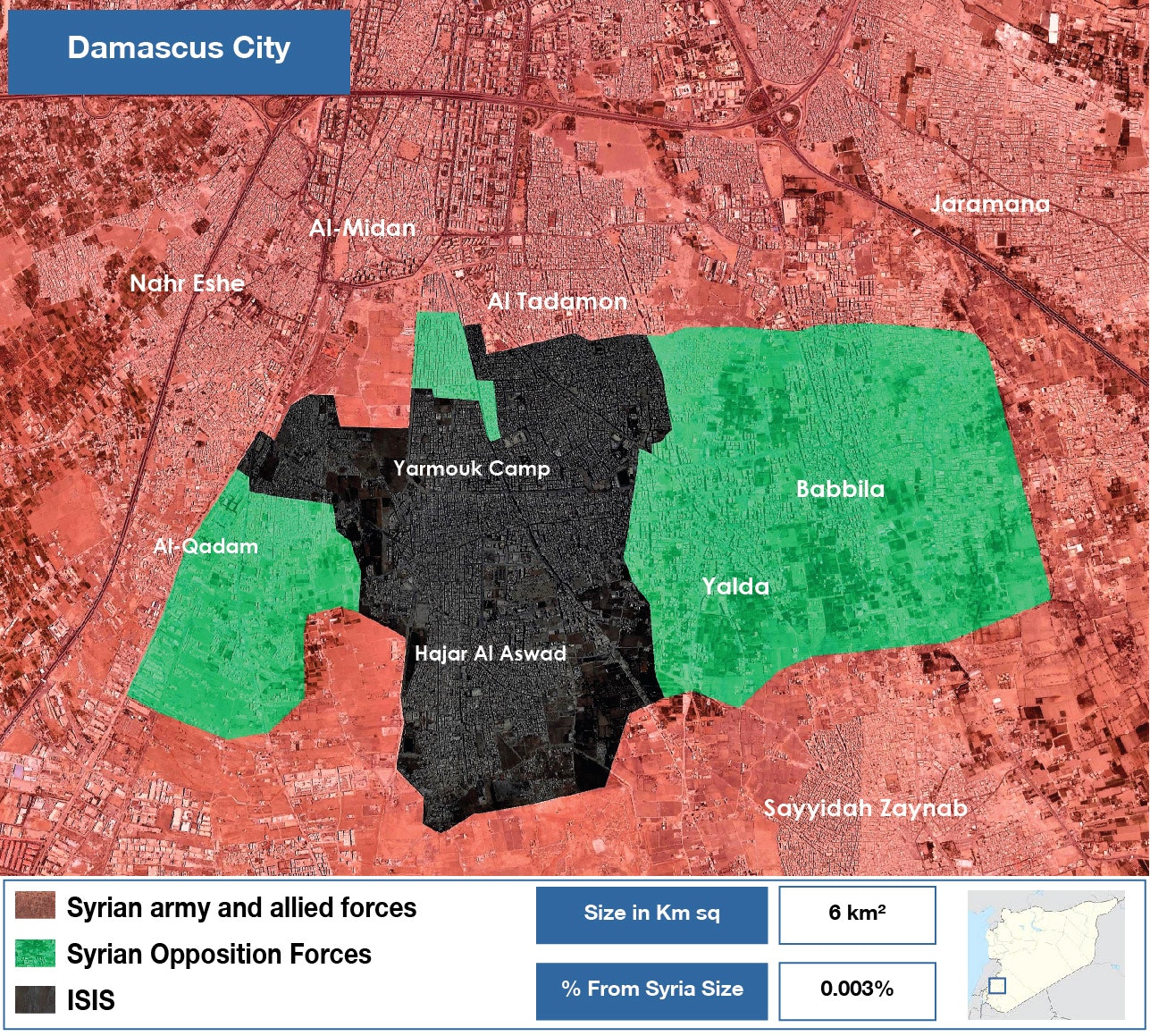

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS south of the Syrian capital, Damascus.

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS south of the Syrian capital, Damascus.

By Omran for strategic studies -Nawar Oliver

While it’s unclear if ISIS timed the attacks as a response to the U.S. and Russian statements, the militant’s new offensives serve as a reminder that it may be too soon to sound the death knell for ISIS in Syria, experts said.

At the height of its power in 2015, ISIS commanded territory in Iraq and Syria larger than the size of Ireland. This year, however, separate Russian and U.S. military campaigns pushed militants out of all their major strongholds across the two countries. While Putin and Trump call this a complete defeat others remain skeptical.

“I think that there’s a bit of ambiguity and confusion with regard to what a defeat might look like,” Simon Mabon, a lecturer in international relations at Lancaster University and co-author of The Origins of ISIS, told Syria Deeply.

“Whilst some will talk of a military defeat and the liberation of Syrian-Iraqi territory, the bigger and arguably much trickier struggle is about defeating the ideology and preventing the group – or a manifestation of it – from re-emerging,” Mabon said.

Earlier this month, Sergei Rudskoi, a senior Russian military officer claimedthat “not a single village or district in Syria under the control of ISIL.”

According to the SOHR, ISIS still controls 3 percent of Syrian territory, or 5,600 square kilometers (2,162 square miles). ISIS is present in southern Damascus, in “large parts” of the Yarmouk camp as well as in parts of the al-Tadamon and al-Hajar al-Aswad neighborhoods, where they are battling government forces.

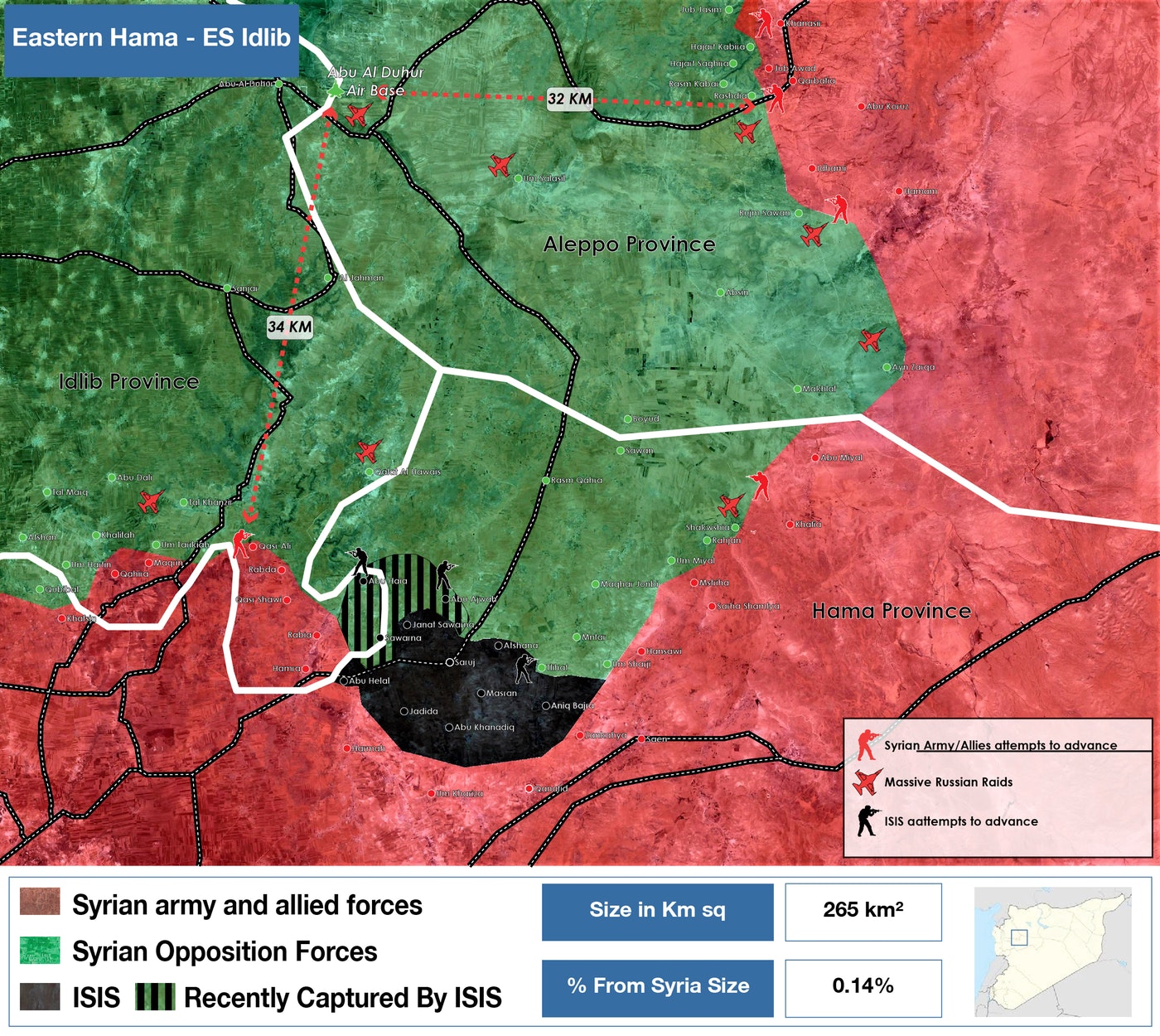

ISIS is also active in desert regions east of the government-held town of Sukhana in Homs province as well as in a small enclave in northeast Hama, where it is engaged in fighting with the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham alliance.

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS in Hama province.

By Omran for strategic studies -Nawar Oliver

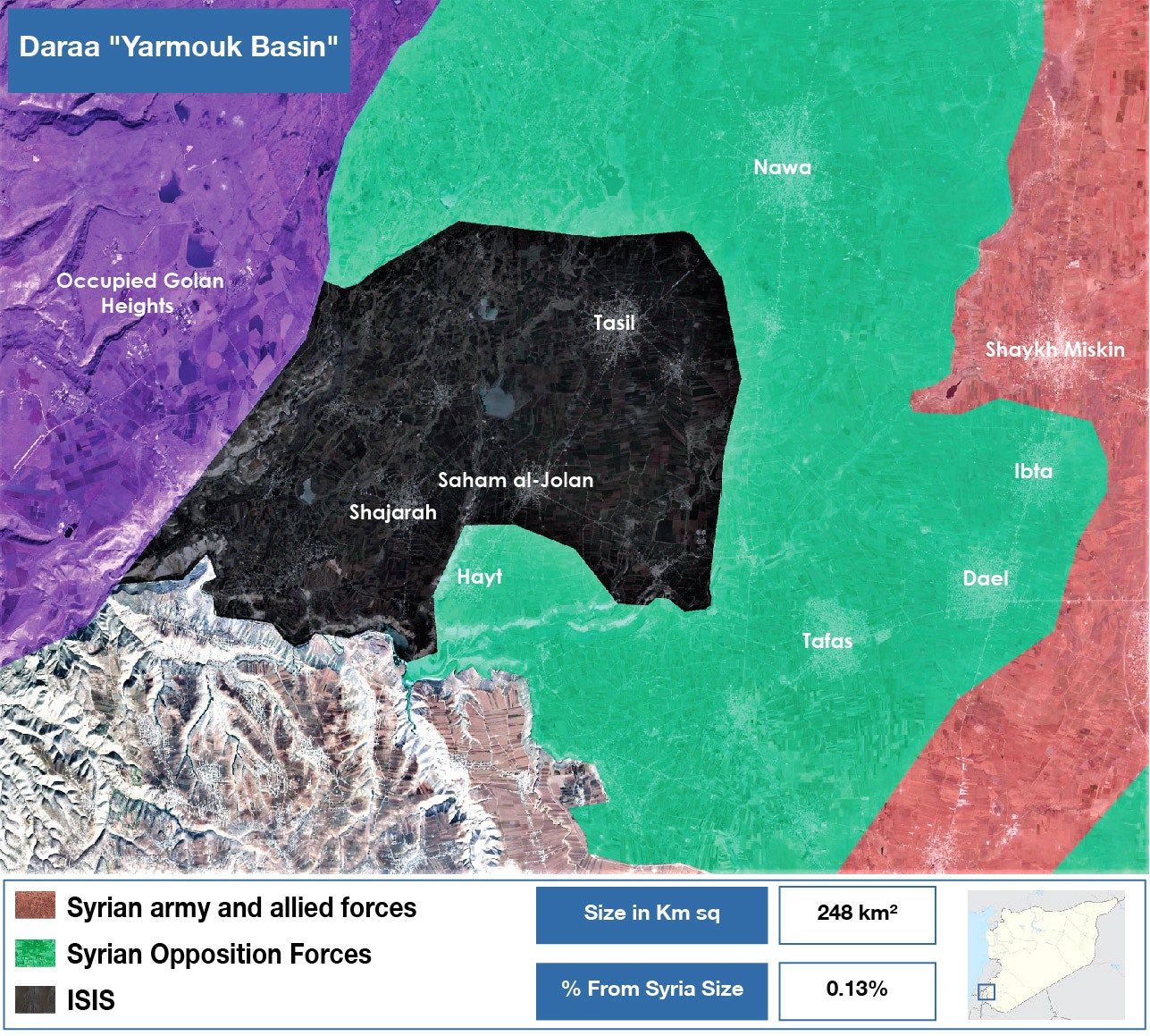

Militants also control at least 18 towns and villages in Deir Ezzor province, where it is battling both the Syrian government and the U.S. backed Syrian Democratic Forces. In Syria’s southern province of Daraa, ISIS controls a small enclave close to the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, where it has previously clashed with rebel forces.

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS in the southern province of Daraa.

By Omran for strategic studies -Nawar Oliver

Some White House staff and French President Emmanuel Macron said they were wary of Russia’s claim of victory on the ground. “We think the Russian declarations of ISIS’ defeat are premature,” an unidentified White House National Security Council spokeswoman told Reutersin a report published Tuesday.

“We have repeatedly seen in recent history that a premature declaration of victory was followed by a failure to consolidate military gains, stabilize the situation, and create the conditions that prevent terrorists from reemerging,” she said.

The militant’s last vestiges of territory are coming under severe strain by a wide array of rivals. It is only a matter of time before militants are driven to rugged hideouts in Homs and in the Euphrates Valley region. But as military battles subside across the country, a slow-grinding and methodical campaign should kick off to prevent an ISIS resurgence.

“To properly talk of a victory over the group, the conditions that gave rise to them must be eradicated. By that, I mean that people must improve their living conditions, be granted better access to political structures and to be able to exert their agency in whatever way they wish,” Mabon said.

“To fully defeat ISIS, such conditions must be addressed, preventing grievances from emerging that force people to turn to groups such as ISIS as a means of survival,” he added.

However, with military operations against militants still underway, there has yet to be any significant attempt to battle the ideological residues of the group or address the grievances that led to its emergence.

In an attempt at countering ISIS’ ideology, activists and Islamic scholars set up the Syrian Counter Extremism Center (SCEC)in the countryside of Aleppo in October. However, the so-called terrorist rehabilitation center has limited funding, giving it little ability to prevent the return of ISIS, especially after hundreds of ISIS-affiliated militants and defectors flocked to opposition-held areas in northern Syria in recent months.

Iraq, whose military also declared victory over ISIS this month after driving militants from their major strongholds, is already confronting a possible return of the extremist organization, in a further indication that claims of victory are premature.

According to the Iraq Oil Report, a new armed group, hoisting a white flag that bears a lion’s head, has recently appeared in disputed territories in northern Iraq. Citing local leaders and Iraqi intelligence, the report claimed that some members of the new group are known to have been members of ISIS. This has given rise to fears that ISIS may be “regrouping and rebranding for guerrilla warfare,” the report said.

A regrouping of ISIS would not come as a surprise, especially since militants can still capitalize on grievances in marginalized Sunni communities across Iraq and Syria.

“Across both states, Sunnis had been persecuted and marginalized, politically and economically, along with the physical threat to their very survival,” Mabon said.

“Whilst many are fearful and angry of ISIS, the deeper issues of marginalization and persecution remain.”

Russia’s Brittle Strategic Pillars in Syria

With unreliable allies and a lack of experience with local power dynamics, Russia’s influence in Syria is built on fragile foundations

With political control fragmented among local powerbrokers in Syria, Russia’s overreliance on the Assad regime to protect its interests is a strategic threat. Despite current intersecting interests, neither the regime nor its Iranian allies are reliable partners. Competing and conflicting interests may finally come to a head once a political solution begins to take shape and Syria embarks on reconstruction, particularly in light of new regional arrangements.

Belying Vladimir Putin’s claim during his surprise visit to Syria that Russia is pulling back, these factors have in fact driven Russia to work to develop new tools that will enable it to maximize its gains and safeguard its interests in Syria.

Russian strengths and weaknesses

Russia reportedly has seven military bases housing approximately 6,000 individuals in Syria, and an estimated 1,000 Russian military police spread throughout the de-escalation zones and areas recently reclaimed from the opposition as a result of reconciliation agreements. Russia has also entrusted several private security forces with the task of carrying out special missions ostensibly in its war against ISIS and with protecting Russian energy installations and investment projects; these include the paramilitary group, ChVK Vagner, which, according to sources, has around 2,500 individuals on the ground in Syria.

But Russia realizes that it is not strong enough to guarantee its interests in Syria on its own and that it must rely on local partners to do so. Hence, Moscow is making efforts on two separate fronts. One is vertical – aiming to establish lasting influence within state institutions, particularly the military and security apparatus – by investing in influential decision makers, such as General Ali Mamlouk, director of the Baath Party’s National Security Bureau, and General Deeb Zeitoun, head of Syria’s General Intelligence Directorate, two of the most prominent security men.

The other is horizontal in nature. Russia is keen to develop relationships with local powerbrokers directly in order to build inroads with local communities with a view to balancing Iran’s growing influence within Syrian society. These relationships could be used as leverage to sway political negotiations towards Russian interests, while also recruiting them as local partners and guarantors for Russian investments.

Reaching out

The Russian Reconciliation Centre for Syria at Hmeimim Airbase plays a key role in communications with local powerbrokers; however, the communication mechanism and those responsible for it vary according to who controls the relevant areas. In coordination with the National Security Bureau, Russia has been able to engage with local powerbrokers in regime-controlled areas, including various political parties, local dignitaries and religious and tribal leaders, through Reconciliation Centre staff. It has also been able to communicate with the Kurds via military and security channels like Hmeimim Airbase and the Russian Ministry of Defence or via political channels managed by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in coordination with Hmeimim.

But Russia faces a dilemma communicating with local powerbrokers in opposition controlled areas and dealing with the influence of multiple regional actors. To overcome those challenges, it has employed several mechanisms to communicate with these groups in an attempt to co-opt them, using important political figures such as Ahmad Jarba to communicate with local leadership in besieged areas like Homs and Eastern Ghouta, and resorting to local reconciliation committees (primarily made up of local dignitaries and technocrats associated with the regime) that possess their own communication channels that can be used to communicate with the local opposition, as was the case in Al-Tel shortly before the Free Syrian Army’s withdrawal.

According to an activist from northern Homs, Russia is also very much dependent on cadres of Chechen Muslim military police, fluent in Arabic, to communicate with local leaderships. In addition, Moscow has used Track II diplomacy to network with local powerbrokers and open up back channels through relationships with regional powers.

Russia has so far employed the ‘carrot and stick’ model when communicating with local powerbrokers to ensure its influence, offering up benefits like security protection and financing, while guaranteeing them a place at the negotiating table and a share of reconstruction revenue. But based on past form, more heavy-handed measures to pressure local powerbrokers, such as making them targets of future military operations or playing on local rivals to marginalize or giving preference to one group over another in a political solution and reconstruction arrangements, remain on the table.

Enduring challenges

Although it has made strides stabilizing its military presence and legitimizing its security arm in Syria, Russia still faces challenges generating leverage within state institutions and Syrian society where Iran opposes Russia's efforts. The regime’s many centres of power, reliance on militias and weak institutions limit Russia’s efforts to consolidate its influence in the rest of Syria. Similarly, Moscow is finding it difficult to communicate with Syria’s many powerbrokers and differentiate between their demands, references and allegiances to other regional powers – making Russia’s strategic pillars in Syria all the more fragile.

Workshop on Cooperation Prospects in Institutional Reform and Restoring Stability in Syria

Omran Center for Strategic Studies organized a workshop in partnership with and hosted by the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP). The workshop discussed international cooperation prospects on institutional reforms necessary to restore stability in Syria. This workshop took place at GCSP on 21-22 September 2017.

The workshop brought together 35 experts and researchers from the US, Russia, Germany, the UK, France, Australia, Switzerland, and Syria. The participants gathered for two days to exchange views on stability in post-war Syria.

The vibrant discussions focused on the place of Syria in the West-Russia global power contest; institutional reforms within the political transition; prospects of cooperation on reconstruction; local governance; de-radicalization and counter-terrorism; and disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR).

The workshop is part of the Syria and Global Security project, jointly run by Omran and GCSP. It is an initiative to offer a platform for collective informed discussions on Syria that eventually could build bridges between experts and researchers in order to bring peace and security to Syria, and the region.

Mr. Yaser Tabbara poses the question of international accountability in Syria's war

Mr. Yaser Tabbara Researcher at Omran Center for Strategic Studies, poses the question of international accountability in Syria's war, after a regime soldier has been prosecuted for a war crime. Mohammed Abdullah claimed asylum in Sweden in 2015. But activists recognized him from online photo, smiling, surrounded by dead bodies. So, instead of receiving refuge, he got an eight-month prison sentence for mistreating corpses.

Yaser Said: 8 month for something so horrific is a little bit more than a slap on the rest, but still it is significant being the first incident of international accountability for such crimes, he added that the lack of evidence are considered a major problem and a weak link for the universal jurisdiction. He answered the question of "what about the head commander committing these crimes?"; International criminal justice lacks enforceability, the Russian and Chinese have been putting the main obstacles to the international criminal court, that is purely because political reasons.

Yaser ended the interview saying that not all soldiers should be banned from asylum, it's all depend on their acts on the ground and on what they were force to do while the regime was committing his crimes, and to attain absolute justice is something most of the Syrian have given up on

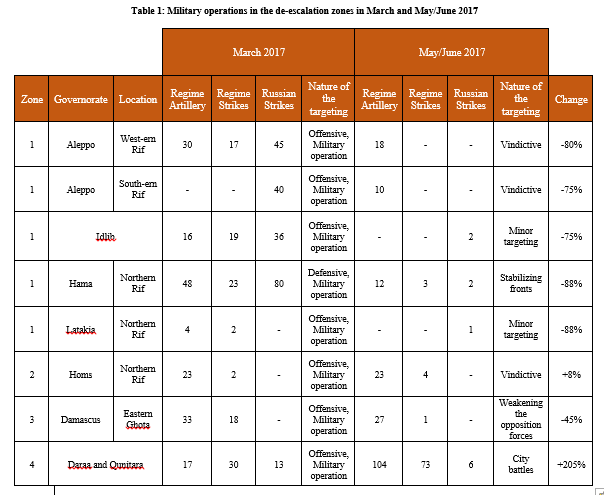

De-escalation Zones: A Cloak to Refocus on the East

Executive Summary

-

The de-escalation zones from the latest Astana meeting on Syria aimed to freeze the conflict on the western fronts in order to deploy the regime and its allies’ forces to prevent a total loss of the eastern territories to the American-led Kurds and opposition forces. Securing Tehran-Baghdad-Damascus-Beirut free passage is strategically more important compared to Idlib or Ghota at the moment.

-

The agreement was largely observed by all parties (Russia, Turkey, and Iran) and resulted in an immediate reduction in military operations in the selected zones. Compared to the level of operations in March 2017, May/June 2017 witnessed an 80% reduction in western Rif of Aleppo, 75% in Eastern Rif of Aleppo, 97% in Idlib, 88% in Hama, 80% in Latakia, and 45% in Ghota of Damascus. There was a slight rise in military operations in Homs (8%) and a radical increase in Daraa (205%) but that increase was mainly attributed to vindictive offenses like in Homs, or tactical deterrence to the opposition as in Daraa’s al-Manshia district.

-

The latest Geneva talks ended with no significant outcome, probably in anticipation of settling the current competition over Raqqa and Dir Ezzor. It is unlikely for Geneva to restore its significance before stabilizing the military situation and before the US and Russia move towards a serious political settlement.

-

It is still too early to determine if the de-escalation zones can serve as a basis for a Russian strategy to stabilize the situation on the ground and foster an environment conducive to a political solution. The outcome of the battles on the ground in the East and the sustainability of ceasefire in the West will determine such an outcome. Neither easy nor quick dominance in the East is in sight for either side. Particularly because of the proxy nature of the operations, lack of cohesion between the participating forces, and unprofessionalism of the local forces aligned with the Americans (Kurds and opposition forces) and Russians (tribal forces and Fifth Corps).

-

Nor will there be a clam west, as HTS (al-Nusra coalition) will aim to expand and exhaust the moderate forces with potential reactions from the latter. Accelerated foreign contact, including by the Russians, with the Local Administration Councils (LACs) in the de-escalation zones is expected in order to secure influence during the transition period.

-

This paper argues that the political opposition should unite its negotiations delegations and increase its capacity and legitimacy. The military opposition should support the political process and provide views on its role in the future. The LACs should focus on their service delivery role and improve their capacity to meet the tasks of reconstruction and return of refugees. More important for the Local Councils is to avoid local politicization and alignment with either regional or global actors in order to protect their neutrality as guarantors of a stable future for Syria.

-

The US and EU should support forming a united negotiation delegation for the opposition as a political solution might be looming on the horizon, especially after the situation in a post-ISIS Raqqa and Dir Ezzor settles down. Notably, engagement in Russian-led Astana talks is important to develop critical ideas on a US-EU/Russia cooperation in the transitional period.

-

Russia should support the legitimacy of the opposition delegations and refrain from undermining their efforts to effectively represent their Syrian constituency. More strategically, Russia should approach to the Local Councils, support their professional service delivery, and coordinate with their EU sponsors to assure fruitful cooperation in preserving their role in the future.

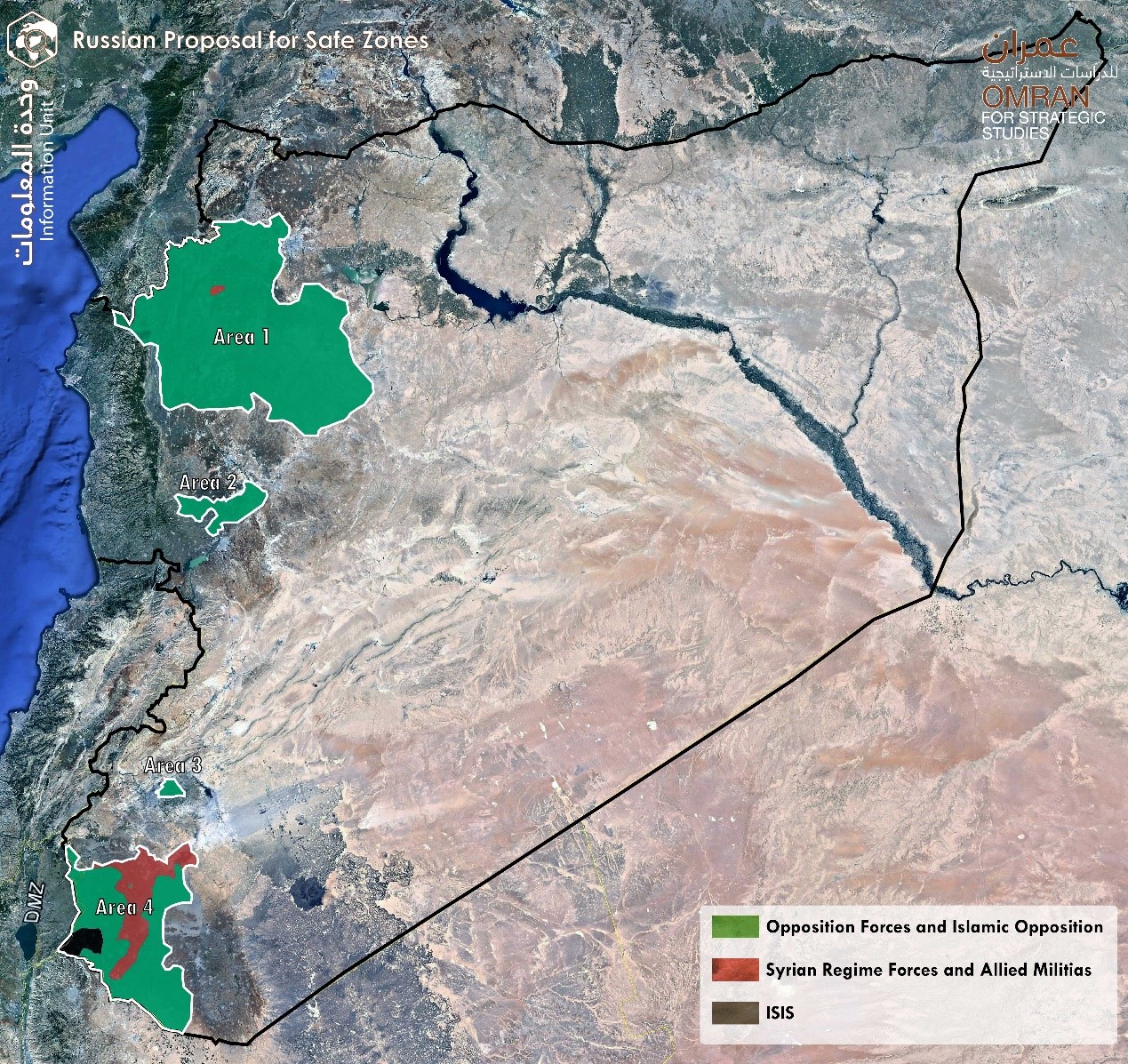

Map No. (1) Russian Proposal for Safe Zones

Introduction

The latest two peace negotiation rounds on Syria ended with postponing the serious discussions until after the dust settles in the east of Syria. The Astana meeting in Kazakhstan produced an agreement on de-escalation zones, supported by Russia, Turkey, and Iran and opposed by Syrian opposition representatives. Not surprisingly, the Geneva talks did not break the low ceiling of expectations and ended where it started. The de-escalation zones serve Russian interests on many fronts, the most important of which is freezing the West “hot spots” (Idlib, Hama and Homs) to focus on the eastern front where Russia aims to disturb the American-led operations to recapture Raqqa and Dir Ezzor on the border with Iraq. The post-ISIS-controlled areas constitute the next battleground and are, to a large extent, the determinant of the final balance of power among all parties in future negotiations. While the eastern fronts will be fluid and hardly stable, the western fronts will not be calm either.

A few weeks before signing the agreement in Astana, there was an immediate reduction in military operations in the selected zones. Compared to the level of operations in March 2017, May witnessed an 80% reduction in western Rif of Aleppo, 75% in Eastern Rif of Aleppo, 97% in Idlib, 88% in Hama, 80% in Latakia, and 45% in Ghota of Damascus, according to the information unit at Omran Center. Some exceptions to the main reduction in hostilities were observed in Homs (8%) and Daraa (205%), with some vindictive offenses in Homs and tactical deterrence of the opposition forces occurred in Daraa.

The opposition forces (i.e., HTS, Ahrar al-Sham, and some MOC-affiliated militias) in late April has occupied al-Manshiya district in southern-Daraa and threaten to advance further into the regime controlled areas in Daraa; therefore, the regime aims to stop their advancement by redeploying forces from around Damascus after solving the problem of Qaboon and Barza cities. The Ghaith al-Dalla forces of the fourth division have joined the Shite militias in the south (Hizbullah, Iranian Revolutionary Guard IRG, and the Fatimioun brigades) to stop the opposition advancement beyond al-Manshiya using aggressive, rather tactical, deterrence offenses. (see Table 1 for more details).

This paper addresses the context of the de-escalation zones and provides an overview of the situation in all of the active fronts in the east and west of Syria. It also includes three sets of recommendations to the Syrian opposition (Political, Military, and LACs), as well as recommendations to 1) the US and the EU and 2) Russia.

The analysis concludes that both the Russians and Americans rely on forces that lack central coordination, professionalism, and discipline. Such characteristics weaken control over the operations, hence making it almost impossible to predict their outcome and trajectory. This turbulent and cloudy situation will dominate for an extended period, given the absence of a political framework to accommodate ISIS members after their organization collapses and they escape to new havens. In turn, the western fronts will be busy with HTS attempts to expand geographically and weaken the moderate opposition politically. There also will be an international and regional race to influence the LACs, considered the black horse in any future efforts for stabilization in the de-escalation zones through humanitarian aid, the management of the return of refugees, and reconstruction shall security guarantees are offered.

Information Support Unit, Omran Centre for Strategic Studies

De-escalation in the West, Escalation in the East

While attention is refocused on Raqqa and Dir Ezzor in the east of Syria, the latest agreement signed in Astana helps to freeze the western fronts in order to reallocate resources and concentrate forces for the upcoming battles in the East. The fall of both Raqqa and Dir Ezzor to America’s proxies limits Damascus’ control over the borders, cuts Iranian routes from Tehran to Beirut through Baghdad and Damascus, and empowers America’s grip over both Iraq and Syria.

The protracted war has exhausted the regime forces and devastated its capabilities, and the long line of active fronts in the West has distracted its allies’ attention to the slow developments in the East. The advancement of the Syrian Democratic Forces towards Raqqa and the Southern Front opposition forces towards Dir Ezzor alerted the regime to a near loss of the borders with Iraq. There was a severe need to reallocate the regime from Idlib and Homs, where they can revert to them later, to the eastern fronts, where it is more pressing to secure a foothold.

The new battle needs more manpower and expertise. For these, the Russians and Iranians rushed to organize the tribal forces and integrate them into the Fifth Corps under Russian command. Hizbullah has recently, and rather quickly, given its positions in the South to the Russians and its positions on the Syrian-Lebanese borders to the Lebanese Army; Hizbullah redeployed their forces close to Palmyra. The latest efforts of Hizbullah serve two purposes: 1) to release tension with Israel and hence avert an Israeli attack on Hizbullah inside Syria, and 2) to use its shrinking manpower more strategically to protect its supply line from Tehran.

Recent news coming from Syria was dominated by the American alliance strikes against a military convoy for the Shia militias approaching al-Tanaf crossing, which was captured recently by the American-led forces. Days later, and in a sign of resolve, the alliance forces air-dropped brochures that “advises” the Shia militias to refrain from further approaching opposition-controlled areas. Russia might have to negotiate with the Americans to secure a place on the borders for the Iranians, but that will come at a high price and only if the Russians succeed in interrupting the connection between the Kurds coming from the North and the Opposition groups advancing from the South.

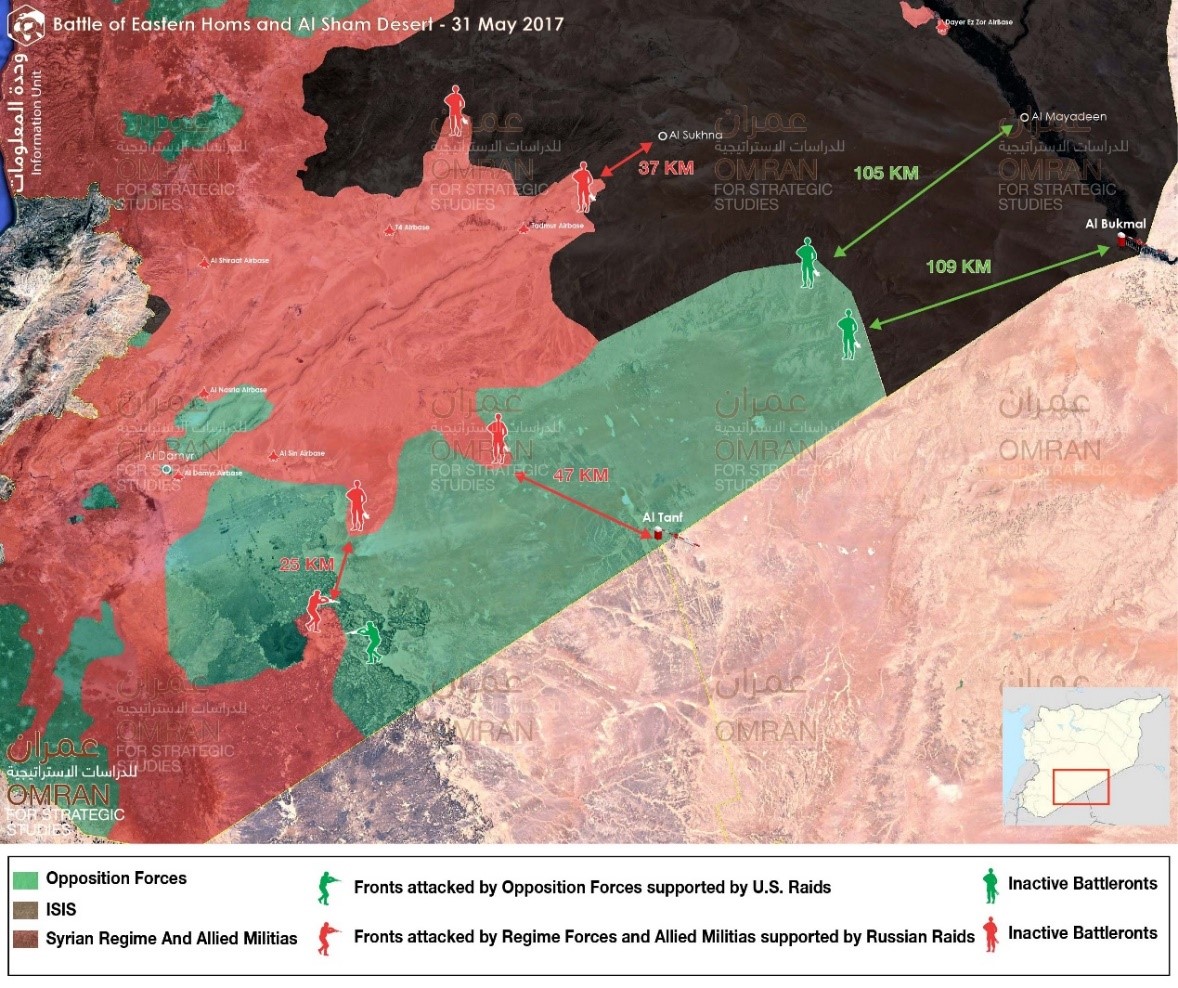

Map No. (2) Battle of Eastern Homs and Al Sham Desert- 31 May 2017

Map No. (2) Battle of Eastern Homs and Al Sham Desert- 31 May 2017

This context shows that the de-escalation zone agreement was neither a Russian secret plan to divide Syria, nor a Russian trap for the U.S. and its allied groups. It actually reflects a pressing need for Russia to freeze the conflict for six to twelve months in the areas that have no strategic urgency, such as Ghota in the South, where Israel is concerned, or where in-fighting and Turkish influence will shape the situation in a less costly way compared to a direct intervention, like in Idlib. At this moment, Dir Ezzor is strategically more important than Idlib, and Nura is less of a threat compared to losing the borders with Iraq to the Americans.

Controlling the borders will change many equations for the regime and its allies: it will challenge its attempts to reclaim control over all of the Syrian territories; it will block the Iranian routes to Hizbullah; and it will give Americans the upper hand in both Syria and Iraq. Russians have tried to avoid confrontations with the Americans since their intervention in 2015, and such a scenario with American-proxy domination of the East and South might lead to undesirable tensions. More important, it is possible that at any moment the pressure of American proxies from the East and South on the regime areas will reverse the military vulnerability that Russia has successfully avoided in Syria so far. Consequentially, it is possible that Russia will be forced to accept a settlement that is not optimal to its interests.

The details of the agreement promise a successful implementation, but the absence of any follow-up or enforcement mechanisms make any euphoria disappear. There are sections of the agreement on international forces and monitoring mechanisms, guarantors, humanitarian access, refugees return, and reconstruction—all dependent on moderate forces restoring security and fighting terrorist groups. The possibility that moderates will be blamed for future acts of terrorists may cause rifts. The moderates will have to either essentially self-destruct by intensifying the in-fighting or face the threat of invasion or bombing by the Russians and the regime. The latest coalitions of HTS (al-Nusra coalition) will not be weakened or reversed before reaching a comprehensive political solution that could encourage small groups and individuals to defect and motivate the militia as an overall body to engage in a national Syrian military and political effort that meets its expectations.

Within the context, rather than the text, of the agreement, Turkey has agreed with Russia to deal with HTS in Idlib, an arduous task. Without a political settlement, Turkey will find itself facing increasingly disgruntled military groups that have the capacity to threaten the depth of the Turkey. There is little in the agreement that justifies the Turkish presence or its acceptance of the Iranian guarantees. However, given the Turkish sensitivities towards any expansion of the Syrian Democratic Forces, which is dominated by the YPG and its PKK connections, Turkish cooperation with Russia becomes less questionable. The Turks have an interest in depriving the Kurds from having a seat at the negotiating table to determine Syria’s future. Moreover, with current challenges in Turkish-American relations, any increase in U.S. presence in both Syria and Iraq potentially diminish the regional influence of Turkey. The Turks find themselves implicitly allying with the Russians and Iranians, against the Kurds and the Americans.

The US and the EU did not pay attention to the Astana conference from the beginning in order to avoid reducing the importance of Geneva to Russian-led talks and to comply with their Iran marginalization policy. Militarily, The Americans did not respond to Aleppo’s fall or Idlib’s suffer because there were considered out of their strategic influence zones. Alternatively, Americans invested heavily in the Kurds and the southern groups in cooperation with the UK and Jordan in order to capture ISIS-dominated areas in the East. That will not only increase the areas under their control but also will increase the US legitimacy as successful forces in fighting terrorism. The US hope that strategy will create a new situation that will force the regime and its allies to negotiate seriously, by American terms, in Geneva or otherwise. In the meanwhile, the Europeans did not break their silence on Astana either. The EU focuses only on Geneva and is suspicious of Russia’s efforts. The Russians failed to buy their support to Astana despite the incentives inserted in the agreement by promising the return of refugees and reconstruction.

Indetermination in the East, and slow fire in the West

Against the clarity of the parties’ plans, the realities on the ground might tell a different story. Looking more closely at the formation of the competing forces racing towards Raqqa and Dir Ezzor, it appears that they are neither professional nor disciplined nor coherent in their composition or end goals. That will likely result in a non-linear path towards domination, lasting a long time and resulting in a high number of civilian causalities. The Syrian Democratic Forces are perceived to be YPG-dominated, which may provoke an armed resistance by the Arabs of Raqqa, especially in cases of brutal conduct against civilians conducted by the YPG. That scenario will slow the SDF’s advancement towards the South and will force it to prematurely withdraw leaving a power and governance vacuum behind. The rest of the American-supported groups, such as Maghawer al-Thawra, the Lions of Sharkia, Shahid Ahmed Abdou Brigades, and Ahmed al-Garba forces in al-Hassaka, are no more disciplined and will bring the same problems.

The situation for the Assad regime and Hizbullah might look brighter, but threats of American air attacks and Russia’s decision to refrain from a direct confrontation will neutralize this advantage. The rest of the regime-aligned forces will include the nascent groups working under the Fifth Corps, such as the tribal forces, whose capabilities are still questionable. The Russians bet on filling the vacuum in Dir Ezzor after the failure of the American-led forces to establish control. That gamble indicates that the battle will not be settled any time soon and its outcome is uncertain.

The distraction from the western fronts does not exclude them from the spot light. HTS (al-Nusra coalition) will try to expand geographically and attract more groups and individuals to its coalition in order to weaken the moderates’ body. That might be countered if the newly formed Turkish-led forces succeed in uniting all moderates under the Euphrates Shield zone and advances into Idlib. Other interesting events include the race to contact and empower the LACs in Idlib and northern Aleppo as a humanitarian and development player in a future political transition or a stable ceasefire. Europeans and Americans have been a strategic partner of the LACs, and now also the Russians are looking for a place in Idlib and other de-escalation zones. All powers will seek to improve the capacity and legitimacy of the LACs, but competing over the political alignment of the LACs is counterproductive. The use of LACs as political tools for any party will undermine their role as professional service providers and as a popular medium between the government and the local population.

Recommendations for the opposition and international players:

1- The political opposition: Starkly, there were no Syrian signatories to the agreement, neither the government nor the opposition. This suggests that Syrians have lost control over the trajectory of the war in their own country. In Astana, the Syrians are observers rather than participants in any discussions concerning their cause, a position in Astana that disregards them no less than in Geneva. It is of interest to all parties, except for the Assad regime and Iran, to support the opposition in both conference. For that, there is a need to increase the capacity and legitimacy of the delegations. This can be achieved through:

- Uniting the delegations of both Astana and Geneva in consultation with the opposition allies. Merging the military weight of the Astana delegation with the regional and international recognition of the Geneva delegation will make one solid front in both venues. This will not happen without a show of will from the two delegations and without some pressure on the allies—specifically Turkey and Saudi Arabia. These efforts entail recalibrating the current political and military establishments of the opposition in order to accommodate such overdue restructuring.

- Increasing the technical capabilities of the delegation. Ever since Geneva I meetings in 2012, the opposition has needed to boost its capacity to conduct negotiations with the regime regarding myriad issues from humanitarian coordination to security reform, from reconstruction to the return of refugees. It is a mistake to assume that a constitution and elections will dominate the discussions. For example, the current de-escalation zones agreement includes minute details on the observers’ mechanisms and the international force composition and mandate, which are often out of the ream of expertise of unspecialized military officers. The failure to provide such capabilities will lead the delegation to blindly agree to unfavorable terms or unwittingly refuse to sign potentially favorable agreements.

- Increasing the legitimacy of the united delegation. Two dilemmas face the Syrian delegations in both Astana and Geneva: one is weak communication with their wider constituencies inside and outside of Syria; the other is the disconnect among local actors in the opposition-controlled area.

- Communicate with Syrians inside and outside of Syria. There is a need to improve the level and means of communication with Syrians in general, and especially those who count as natural constituency inside and outside of Syria. Direct messages 1) before negotiation rounds to explain the goals, 2) during the negotiations to elaborate on the development, and 3) after the end of rounds to summarize and hint on the future steps. It is possible to lose the message when there are too many delegations, each claiming to represent the Syrian cause.

- Communication with local elements in Syria. The more local support the more legitimacy is secured in the eyes of the international community. In Astana, the militias represent power brokers on the ground, but they still cannot speak for other elements like local councils. Geneva talks represent political elements and regional clout where more players on the ground are excluded. The political body of the opposition is responsible for securing the physical needs of its constituency and representing its demands. The failure to play that role casts doubt on its legitimacy.

2- The military opposition: The political opposition might look incompetent and unrepresentative to Syrians on the ground who have made significant sacrifices, but without the opposition it would be doubtful to receive political acknowledgement from the international community and hence weaken the possibility to transform the military achievements of Syrians on the ground into an institutionalized political gain. The military factions have hard tasks as they are responsible for defending their territories, as well as supporting the political process at once. The overall weight of the Syrian opposition does not give room for more than one delegation. Therefore, we recommend the following:

- Pressuring to unite the negotiations delegation. The political opposition needs the militias’ help to coordinate the efforts and to lobby the allies in order to support merging the two delegations.

- Providing a vision for the militias’ role in the transition period and the future Syria. Specific answers about the militias’ willingness and ability to professionally deliver security during the transition period, disarmament conditions, and integration in one united Syrian Army are much needed. Without clear and detailed answers to these questions, the negotiations process will be harder and all of the opposition’s sacrifices will be wasted. That eventually will transform the discontented fighter into a ticking time bomb in the future.

3- The Local Councils: The LACs are an important Syrian asset for future stabilization and should be preserved at any cost. Therefore, we suggest the following:

- Focus on professionalism in delivering services indiscriminately to all Syrians regardless of their faith, gender, and ideology.

- Boost the LACs legitimacy by observing the elections cycles and avoid any political or ideological aligning.

- Assure transparency in all transactions with donors to avoid any side deals with any harmful regional or international coalitions in the future.

4- The US and the EU: Both entities can enhance the substance of the current negotiations in Astana and Geneva, as well as facilitate the institutional transition through the following:

- Stepping up the US and the EU involvement in Astana on the political and technical level to assure better agreements in terms of implementation and following-up mechanisms. That would make it harder to be ignored and will reemphasize the US and EU’s responsible position towards the Syrian cause.

- Supporting efforts to unite the Syrian delegations, both financially and technically. It is worth noting the importance of building a Syrian expertise base instead of the unsustainable reliance on costly and unproductive western consultancy companies.

- Respect the professional and neutral aspects of the LACs and avoid pushing them into a polarized regional and international muddy field.

5- Russia: There is a big room for Russia to reach quick and more effective results in resolving the conflict, improving the substance and outcome of the ongoing negotiations in Astana and Geneva, and facilitating the institutional transition through the following:

- Avoiding undermining the legitimacy of the opposition and show goodwill by not targeting their local constituencies and deterring the regime and the Iranians from the same. A strong and legitimate opposition can uphold the agreements and assure their implementation, while a weakened one is a guarantee for instability and prolonged war.

- Facilitating access of humanitarian aid to the opposition areas to build trust with Syrian citizens and also to support the legitimacy of the opposition in their eyes.

- Establishing a communication protocol with the opposition delegation to Astana and Geneva in order to improve the substance and outcome of the negotiation rounds. The opposition delegation should obtain all necessary information that enables it to effectively represent its cause and transform the outcome into concrete results.

- Respect the popular representation nature of the LACs and support their role as a professional service and security provider. Avoid any miscommunication that would result in delegitimizing them in the eyes of their constituency or their main sponsors. Russia can be a positive force to bring stability into the opposition areas by securing an environment conducive to the return of refugees and the reconstruction of infrastructure.

- Cooperate with European countries and the US on supporting the LACS. This can be a good venue for trust-building and de-escalation between the US and Russia in Syria.

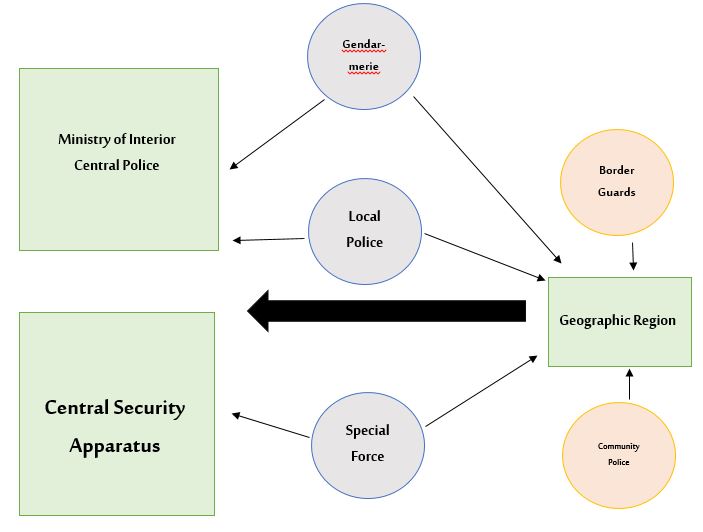

The Security Situation in Syria and Ways to Manage It

Executive Summary

This paper evaluates and scrutinizes the various security apparatuses in Syria, starting with areas under the political control of the regime, then delving into those held by the opposition, and finally looking into the administratively autonomous regions. Elucidating the measures that must be taken to bring the security services under control, the paper presents a preliminary proposal that describes the security sector, it function, and relationship with the center and the periphery. The proposal seeks to strengthen the conditions of local empowerment while also protecting the stability and unity of the country.

First: The Security Situation in Areas Under the Political Control of the Regime

From the time that allied foreign militias began pouring into Syria and local military groups overseen by senior regime officials began to coalesce, the security apparatuses in regime-held areas could no longer be viewed as cohesive and subject to a regulated and centralized security force. The accumulation of the state security apparatuses’ failures and their inability to face the growing uprising helped to push the regime to take a series of measures that eroded its central hold over the security services. This process began with the formation of auxiliary local militias backed by either the Syrian army or state security services. These policies replaced the regime – and its concentrated authority within the military and security establishments – with mercenaries from among the local population belonging to armed militias that have grown and expanded in both size and influence over the past three years.

These groups represent a real danger to the regime if they slip from its control. For instance, if they develop a large base of followers on the ground and establish strong ties with the local community, this could enable them to both negotiate with the regime for control and influence and work with international groups to further their own special interests, which may conflict with those of the regime. Thus, in 2016, the regime made containing these groups a top priority by restricting the institutionalization of these groups and ensuring their loyalty as a way to safeguarding its own survival and achieving both balance and stability. In general, these measures have had the following consequences:

-

Granting local militias with the power to police the local population and carry out military missions among them.

-

Permitting militias’ security and military functions to grow beyond their localities, allowing most to become centralized militias with departments and branches.

-

Militarizing the community and linking its fate to the regime’s survival and continuity. This has increased the scale of the abuses and violations committed in the name of the state and its citizenry.

-

Institutionalizing these militias by virtue of economic necessity and transforming them into entities that encompass both military strategy and centralized security.

-

Creating military wings for political parties loyal to the Ba’ath Party and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP). This has strengthened these parties’ local authority and rendered them partner security forces linked to the state’s centralized security force through shared benefits and interests.

We Find that the Main Security Apparatuses in Regime-Held Areas are the Following:([1]

1. National Defense Forces (NDF)

Formed in summer 2012 and considered to be by far the largest militia to back the regime, the NDF now encompasses over 100,000 volunteers and is comprised of units spread throughout the country that are overseen by the Syrian army and led by General Hawash Mohammed. The NDF started by organizing and training hundreds of volunteers in People’s Committees. These NDF-trained militias resembled the volunteer Basij militia in the Iranian Revolutionary Guard (IRG), which has given rise to the belief that they were created under the guidance of the leader of the Quds Force in the IRG, Qasem Soleimani.

2. Suqur al-Sahara

Established as an “elite force” by Mohammad Jaber – a businessman closely tied to the regime – the Suqur al-Sahara operates in desert areas and is known to have both participated in the al-Qaryatayn offensive and help recover Kessab village on the Syrian coast. The militia is made up of Alawite and Shiite operatives (as well as individuals from the al-Shaitat clan) and is largely dedicated to fighting ISIS. Comprised of trained operatives – including both current and retired army officers as well as young Syrian volunteers – Suqur al-Sahara is the foremost militia specializing in ambushes and carrying out challenging special operations. Moreover, the militia specializes in protecting oil and gas wells as well as the largest weapons stockpile in the country: theMahin Arms Depot.

3. Al-Bustan Militias

These militias are commanded by the director of the Bustan Charitable Association, which established a security branch that attracts Alawites from Syria’s coast. Functionally and administratively, these militias fall under the purview of the local army divisions in their areas of operation and coordinate their operations with the 18th Division. The most prominent of these militias is Kata’ib al-Jabalawi. Operating in both Homs and Ghouta, it is the most independent of the National Defense militias. Another of these militias is the Leopards of Homs, which was in operation between 2013 and 2015 founded by Shadi Jum’a – a confidant of officer Abu Ja’afar (also known as the Scorpion), who founded the Khyber Brigade, one of the NDF’s militias in Homs. The Leopards of Homs preside over the National Shield forces, which coordinate with the Shiite Zulfiqar militias in Damascus.

4. Coastal Shield Brigade Militia

A statement from the Syrian Republican Guard (SRG) in May 2015 announced the formation of the Coastal Shield Brigade. Comprised of recruits paid a salary of up to 40,000 Syrian Lira, this brigade protects the regime’s main stronghold and maintains its readiness to take in new volunteers to serve in the brigade’s ranks for either two years or an indefinite period of time. Rami Makhlouf and the SRG’s Major General Hassan Mustafa have been tasked with leading the militia with the goal of protecting Alawite villages in the coastal areas. The brigade is made up of defectors from mandatory military enlistment and army reserve service, as well as a number of criminals, who are spread out among the villages of Sanobar – outside of Jableh – and Asitamo.

5. Al-Jazeera and Euphrates Assembly

This is a militia that was formed in the Veterans Hall in Damascus. Sources indicate that this assembly comprises citizens of Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa, and Hasakah and is headed by Riyadh Arsan, who is from Deir ez-Zor but resides in Damascus.

6. Political Militias

These militias arose from political parties and have sought to mobilize their volunteers using partisan and political slogans. The most prominent of these militias are:

-

Ba’ath Brigades: This group was formed by Ba’ath Party members in Aleppo by Commander Hilal Hilal in summer 2012 after rebels managed to enter Eastern Aleppo. These brigades later sprang up in Latakia, Tartus, and even have operations in Damascus.

-

The Eagles of the Whirlwind: This group symbolizes the slogan of the Lebanese SSNP, which, in contrast to the national Ba’ath Party, subscribes to the “Greater Syria” ideology. Approximately 8,000 operatives from the Eagles of the Whirlwind, both Syrian and Lebanese alike, take part in operations in Syria. While their main focus is on Homs and Damascus, they maintain a larger presence in the Suwayda Province than the Syrian army.

-

The Arab National Guard: Formed in 2013 as a national militia made up of nearly 1,000 operatives, the Arab National Guard is stationed in Aleppo, Damascus, Daraa, Homs, and al-Quneitra and made up of nationals from several Arab countries, including Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, Tunisia, Syria, and Yemen. The militia is staffed by several generals as well, including: Wadih Haddad (a Palestinian Christian), Haider al-Amaali (a Lebanese intellectual), Mohammad Borhami (a Tunisian politician), and Julius Jamal.

-

The Syrian Resistance: Formerly named the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Sanjak of Iskandarun, this militia is loyal to the regime and follows a Marxist-Leninist ideology. The militia is led by the Alawite Turk Mihraç Ural (formerly known as Ali Kayyali), who possesses Syrian citizenship and is known for carrying out the Bayda and Baniyas massacres.

7. Sectarian Militias (Christian and Druze)

The most notable include:

- Jaysh al-Muwahhideen: This Druze militia declared its establishment at the start of 2013 and operates specifically in Suwayda, Daraa, Damascus, and other Druze areas. Initially founded to protect the Druze community, the militia now, under the leadership of Ismail Ibrahim al-Tamimi, more broadly supports the Bashar al-Assad regime.

-

Sootoro Forces: Comprised of Syriac Christians and a few Armenians, this is a local militia located in Qamishli in Hasakah Province.

-

The Christian Quwat al-Ghadab: Established in March 2013 in al-Suqaylabiyah Province in the Homs countryside to protect the city and its outskirts, this militia is closely affiliated with the SRG.

-

Valley Lions Brigade: This brigade is led by Beshr al-Yaziji and centrally located in the Krak Des Chevaliers and Wadi al-Nasara areas and their outskirts where they recruit local youth supportive of the regime, often enlisting them to spy on their peers in the opposition. This group purports to protect Christians, who populate over 33 villages in the area. Al-Yaziji maintains a number of security relations, the most important being with Major General Jamil Hassan, and also coordinates with both Brigadier General Haythem Dayoub from the Military Intelligence Directorate (MID) and Colonel Mufeed Warda leader of the Mazhar Haider militia, which is directly linked to the state security services. Every fighter in the brigade is a volunteer that receives his or her salary from the state and is treated like a normal soldier or officer in the armed forces. The brigade uses the SSNP’s Marmarita bureau as a headquarters for coordinating its operations, a meeting place, and a center for both processing volunteer requests and enlisting new volunteers under the supervision of party members. In addition, a large number of the brigade’s members participate in combat operations, some of whom have died in battle, including: Fadi al-Shami and Tony Othman from al-Hawash, Firas Massouh from Marmarita, and Ghassoub Awad from al-Tal.

8. Palestinian Militias

These pro-regime militias were formed by Palestinian refugees both prior to and after the outbreak of the uprising. The Palestinian militias and factions that formed within refugee camps and have been active since the beginning of the uprising include:

-

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) – General Leadership: The role of the PFLP under the leadership of Ahmed Jibril stood out for its suppression of demonstrations in Yarmouk Camp at the beginning of the uprising. The PFLP also supported the Syrian army in its assault on Syrian protestors.

-

Fatah al-Intifada: Established in 1983, this militia is led by Colonel Said al-Muragha.

-

As-Sa’iqa: This group represents the Ba’athist wing of the armed Palestinian factions. It is tied to the Syrian Ba’ath Party and is a member of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).

In addition to these factions, the Palestinian Popular Struggle Front and the Palestinian Democratic Union (including the Return and Liberation Brigades) are also active. Likewise, the regime has assembled Palestinian militias within Syria. Some of these include:

-

Galilee Forces: Comprising nearly 4,800 Palestinian operatives, the Galilee Forces are led by Fadi al-Mallah and trained by the Syrian army and Hezbollah. Having fought in the Battle of Qalamoun, members describe themselves as Syrians by affiliation, Palestinians by nationality, and resistance fighters by faith.

-

Liwa al-Quds: Established in October 2013 and led by Muhammad al-Sa’eed (also known as “The Engineer”), Liwa al-Quds is linked to the Air Force Intelligence Directorate (AFID) and is made up predominantly of Palestinians from Aleppo refugee camps, particularly Al-Nayrab Camp. Their last battle was for control over Handarat Camp in Aleppo.

-

Palestine Liberation Army (PLA): The PLA is led by Tareq al-Khadraa and differs from the Palestine Liberation Army that is subordinate to the PLO in that it has participated in a number of battles within Syria. The group’s most prominent battle took place in Adra, while its most recent was in northern Suwayda, during which it lost 13 fighters. The PLA has also fought battles in Darayya and Tell Souane and has participated in the sieges of Muadamiyat al-Sham and al-Zabadani. With regards to structure, the PLA comprises three brigades: “Hattin Forces” headquartered in the city of Qatana in Rif Dimashq, “Ajnadayn Force” headquartered in Mount Hermon, and “al-Qadissiyah Forces,” which are deployed near the city of Suwayda in southern Syria. Theoretically subordinate to the PLO leadership, in practice the PLA serves the Syrian government. Consequently, when a number of officers and personnel refused early on to enter into the Syrian conflict, they were executed in the field.

9. Druze Militias (in special cases they are absorbed within local authorities)

Suwayda Governorate’s neutrality has helped strengthen local militias, which have begun to take control of civilian life in the area. Checkpoints within the governorate are not all subordinate to the government, as some are administered by NDF militias, set up by People’s Committees, or run by an assortment of operatives from the Humat ad-Diyar militia, the SSNP, and the Ba’ath Brigades. According to local observers, these mixed checkpoints are divided up into gateways used to smuggle fuel into ISIS-controlled areas on the northeastern and south-southwestern borders of the governorate. These checkpoints are important sources of looting, collecting royalties from smuggling operations, and trading black market fuel, flour, and cigarette. Also active within the governorate is a militia with a religious veneer controlled by Nazih Jarbou that, along with other armed militias linked to the regime, is tasked with protecting the local community. Those belonging to this militia fall into three main groups: traders, fuel station owners, and those who need their interests protected.

Second: The Security Structure in Opposition-Held Areas

The decentralization of security bodies in areas held by opposition factions has developed as an alternative model to that of the strict authoritarian system that was in its place when the regime held control. Whereas a number of these security bodies have disappeared, others remain active and continue to provide security services. The first authorities that sought to take on security threats were the local councils, as their leaders were forced to deal early on with a number of issues that arose from the country’s new reality, including those related to security. Among these councils’ tasks was the maintenance of public order and the protection of public property.

The local councils’ role in maintaining security eventually faded for three main reasons:

-

Regime military incursions into areas that had fallen out of its control, which led to a collapse of the initial structure of local governance.

-

The increased militarization of the rebel movement and different factions’ assumption of security and military administration.

-

The emergence of experimental policing units formed by defectors from the security establishment.

Generally, local councils’ preference to leave security duties to competent authorities was driven by the following reasons:

-

The need to reorganize their priorities and refocus on services, particularly with the deterioration of the humanitarian situation and service provisions.

-

An unwillingness to cause friction with opposition military factions.

-

The lack of resources necessary to form security bureaus.

Following is a review of the most important security actors in the opposition controlled areas:([2])

First: Rebel Police

The police forces have experienced a marked increase in defections in comparison to the military and security apparatuses, as an estimated 500 officers and thousands of other personnel have defected. Whereas a portion of defectors withdrew from security detail, a number of them have joined opposition security apparatuses in rebel-held areas. These rebel factions have worked in cooperation with civilians, particularly with the increase in popular discontent caused by the rise in theft, crime, and encroachment on public property. By the end of 2011 and start of 2012, the following policing experiments had begun to manifest throughout the country: The Judicial Police in Huraytan and Tell Rifaat, the Revolutionary Security Bureau, and the Revolutionary Outposts in most regions outside of regime control.

This policing experiment became more organized by mid-2012 as a number of these experimental units are still in operation. The most notable include:

-

Free Police in Aleppo and Idlib

-

Police Command in Eastern Ghouta

-

Police Command in Eastern Qalamun and Badia

-

Police Experiment in Homs (internal security)

While there are many experimental units that operate under various names (such as the Maintaining Order Forces, the Revolutionary Outposts, Public Security, Security Councils, and the Judicial Police, there remain local experimental units that never developed a clear institutional structure that went beyond their sectors or regions.

Second: Local Judiciary

In the absence of courts operated by the state judiciary, alternatives have emerged that differ with regards to legal authority, formation mechanisms, work methods, and the nature of jurisdiction and subordination. These include:

-

High Judicial Council in Aleppo

-

Islamic Commission Courts for the Administration of Liberated Areas

-

Judiciary Council in Eastern Ghouta

-

Courthouse in Horan

-

High Court in the Northern Homs Countryside

-

Fateh al-Sham (al-Nusra) Front Courts (previously called Courthouses)

Third: Faction Security Bureaus

From their inception, opposition military factions have formed miniature Security Committees that are tasked with gathering and analyzing information and compiling a list of goals to be worked towards. These experimental committees continued to develop and were placed within the framework of Security Bureaus housed within the structure of the opposition factions themselves. These bureaus can be placed into four categories:

-

Armed Opposition Faction Security Bureaus, including: al-Jabha al-Shamiyya, Jaysh al-Mujahidin, Nur ad-Din Zengi, Rahman Corps, Southern Front Factions, Jaysh al-Nasr, and the Authenticity and Development Front.

-

National Islamic Faction Security Bureaus, including: Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiyya, Army of Islam, and Sham Legion.

-

Security Bureaus Arising from Military Alliances, including: Army of Conquest’s Executive Power, Free Idlib Army’s Security Bureau, Descendants of Hamza and Abu Amara Brigades’ Joint Security Bureau, and the Homs Operations Room.

-

Supranational Jihadist Faction Security Bureaus, such as Jabhat Fateh al-Sham.

Evaluating Security Work in Areas Held by the Armed Opposition

Decentralization is the dominant feature of security administration in areas held by armed rebel factions. This is due to there being no central reference point for administering security. The decentralized security authorities lack institutional character for the following reasons:

-

Multiplicity of authorities: This leads to the creation of conflicting functions, clashing interests, and a lack of both consistency and integration.

-

Lack of manpower and specialized skills.

-

Lack of equipment and logistical support.

-

Lack of strategic planning.

The escalation of chaos in Syria’s rebel-held areas stems not only from a lack of institutionalization and limited capabilities, but also from an increase in threats from rebel opponents. Indeed, there are signs that the security situation in these areas is only growing worse, as indicated by the rise in assassinations and explosions, as well as the increase in criminal activities, such as theft, looting, robbery, and crimes against public decency. This bleak picture is further bolstered by the persistence of detainment, forced disappearances, torture, and the spread of armed gangs, drug dealers, smugglers, and the sale of stolen merchandise. The experimental security units outlined above assume a critical role in both curbing the retreat of viable security mechanisms and fighting terrorist groups, such as ISIS, particularly Aleppo, Rif Dimashq, and Qalamun. This is apparent in their relentless efforts to institutionalize and codify their operations through ongoing coordination with local councils, which are more representative and legitimate than other governing bodies.

Third: The Security Structure in “Administratively Autonomous” Areas

The occupations of security personnel in administratively autonomous areas closely resemble analogous position in regime-held areas before the uprising. Both sets of occupations subscribe to a model of community policing that is commensurate with the political ideology of the ruling party, condones the legitimacy of political detention and community militarization, and that links security directives to the central governing authority. However, Syria’s security establishment suffers from deep conflicts within its institutions as well as duplicity among authorities spread out between regime- and Democratic Union Party (PYD)-controlled areas. Perhaps the greatest danger threatening public security is the PYD’s ideological connection with military and security branches and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which is both separatist and hostile to neighboring countries.

With the outbreak of the uprising, the PYD formed organized cells, some of which were structured as units called the “Revolutionary Youth Movement” led by Xebat Derik, a former commander in the PKK who was affiliated with a number of its institutions and was the first commander of the People’s Protection Units. With the development of the conflict, the PYD’s military and security organizations proliferated, some of which include.([3])

1. People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units

These units rely on volunteer forces and lead major military operations in rural and urban areas that the PYD seeks to gain control of. The general structure of the YPG’s military hierarchy’s is comprised of a general command leadership, followed by a military council and field commanders drawn from different brigades, companies, and regions. In the past, the units’ military legitimacy rested on Article 15 of the “Charter of the Social Contract for Autonomous Democratic Rule” (ratified in the PYD’s first session on 01/06/2014), which states that the YPG comprise the only national institution responsible for defense and the preservation of both territorial sovereignty and peace in provincial lands. Moreover, the YPG serves the interests of the people by defending their objectives and national security. It is estimated that the number of fighters serving in the YPG ranges between 20,000 and 30,000.

2. Self-Defense Forces (HPX)

The Social Contract also ratified the formation of the Self-Defense and Protection Authority on 01/21/2014. Later, on 07/13/2014, the Legislative Council approved the Self-Defense Law, which states that each family is obliged to put forth one of its family members between the ages of 18 and 30 to perform “self-defense duty” lasting six months (nine months as of January 2016). The authority’s mission is to implement laws pertaining to the mandatory conscription of Kurds and is carried out by the PYD in areas under its control. Meanwhile, groups allied with the PYD, such as al-Sanadid Forces formed by the Shammar tribe, implement the policy in their own areas.

3. Core Defense Forces (HPC)

These forces draw their missions and duties from the needsof the autonomous Kurdish region by protecting areas and neighborhoods from attacks. For instance, they set up checkpoints on the main roads leading into neighborhoods, gather information about suspicious individuals in the area, support the People’s and Women’s Protection Units in combat operations, and coordinate with Asayish forces and other security services active in the area.

4. Asayish Internal Security Organization – Rojava

Subordinate to the General Authority, this group operates in al-Jazira and Kobani Provinces under the joint leadership of Commanders Jawan Ibrahim and Ayten Farhad. In the approximately four years since its inception, Asayish has developed the public security services in Rojava by leaps and bounds, now carrying out all security duties and possessing security apparatuses that carry out a multitude of functions. These include the: Traffic Directorate (tirafik), Anti-Terror Forces (HAT), Women’s Asayish, Checkpoints Administration, Public Security Directorate, and Organized Crime Directorate. By the end of 2016, the Public Security Directorate possessed 45 centers, 21 of which were located in al-Jazira, 5 in Kobani, 19 in Afrin, as well as over 195 permanent checkpoints throughout Rojava. There are 4,000 to 5,000 personnel and operatives serving in these different apparatuses.

There are other reserve forces as well, the most important including the Internationalist Freedom Brigade and an assortment of western advisors, which were formed because of the influx of foreign personnel to join the YPG after the battle against ISIS in Kobani. On 06/10/2015 the 25-person brigade officially announced its establishment in Ras al-Ayn (Sere Kaniye) and attracted foreign personnel of various nationalities, however most were Turkish leftists from the Marxist-Leninist Communist Party (MLKP) of Turkey, PKK, Villagers for Turkey’s Salvation (which is the military branch of the MLKP that dates back to 1973), and individuals from Eastern European leftist movements. At this time, a number of organizations began to form and were filled by newly arrived operatives to Rojava. At this time, the brigade divided into two parts: the Bob Crow Brigade (BCB), after the British union leader, and the Henri Krasucki Brigade, after the French communist leader. The Internationalist Freedom Brigade is led by a 30-year-old Kurdish woman named Deniz and is comprised of approximately 200 to 300 fighters.