Emerging Security Dynamics and the Political Settlement in Syria

Omran Center for Strategic Studies collaboration with The Syracusa International Institute, held a workshop on “Emerging Security Dynamics and the Political Settlement in Syria” in Syracusa, Italy, on 18-19 October.

The workshop brought together experts from UN, EU, France, Germany, Switzerland, US and many regional countries. The vibrant discussion tackled various issues including: future of the DMZ agreement in the north, the logic of the Iranian presence in Syria, the political economy of militias, and local security imperatives impact on peacebuilding.

This workshop is the one of many workshops hold under "The Syria and Global Security Project" who is co-run by Omran Center for Strategic Studies and Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP). It aims to offer a platform to build common ground and bridge the gap between the main stakeholders in the Syrian conflict.

Centralization and Decentralization in Syria: Concepts and Practices

Introduction

After seven years of conflict between the people and the Assad regime, Syria is now going through a difficult phase. The nature of the conflict has transformed whereby the role and effectiveness of local actors has been greatly maringalized compared to an increasing role for international state and non-state actors. The role of armed opposition factions has diminished as international military, administrative, and political influence has grown. These armed opposition actors are also in a phase of turmoil as they struggle to survive or integrate under direct international custodianship, after having previously received support from the Northern or Southern Operations Rooms. This process follows the series of meetings in Astana and Sochi, and after the political bodies were domesticated into official negotiating bodies that support the interests of countries with direct influence over them. At the same time, direct Russian influence came to dominate the political, military, economic, and administrative spheres. As a result, the concept of the unified framework of the "regime platform" versus the "opposition platform" in accordance with the Geneva II concept was discarded through the creation of several negotiating platforms on the sides of the opposition, the regime, and the Syria Democratic Forces (SDF).

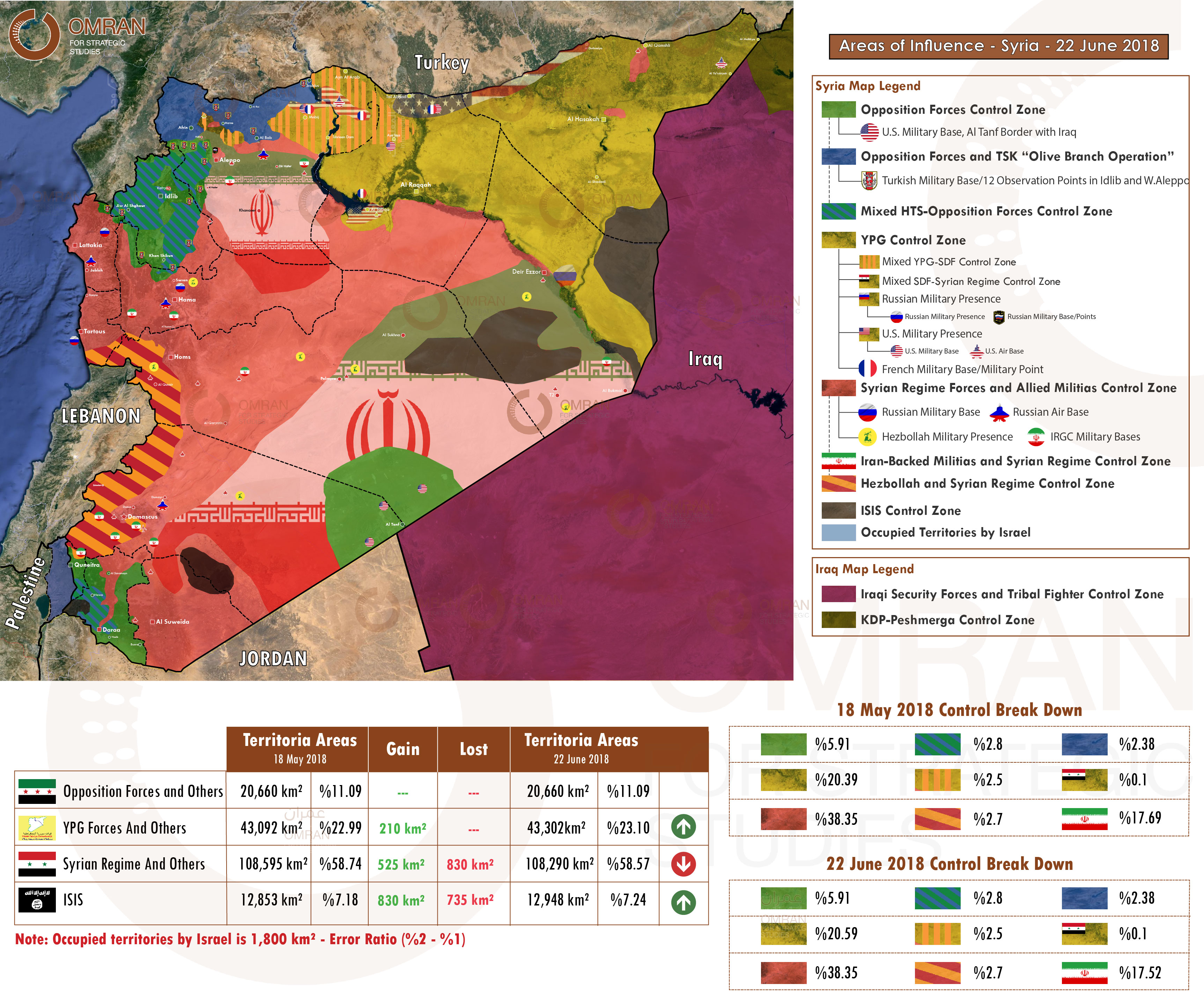

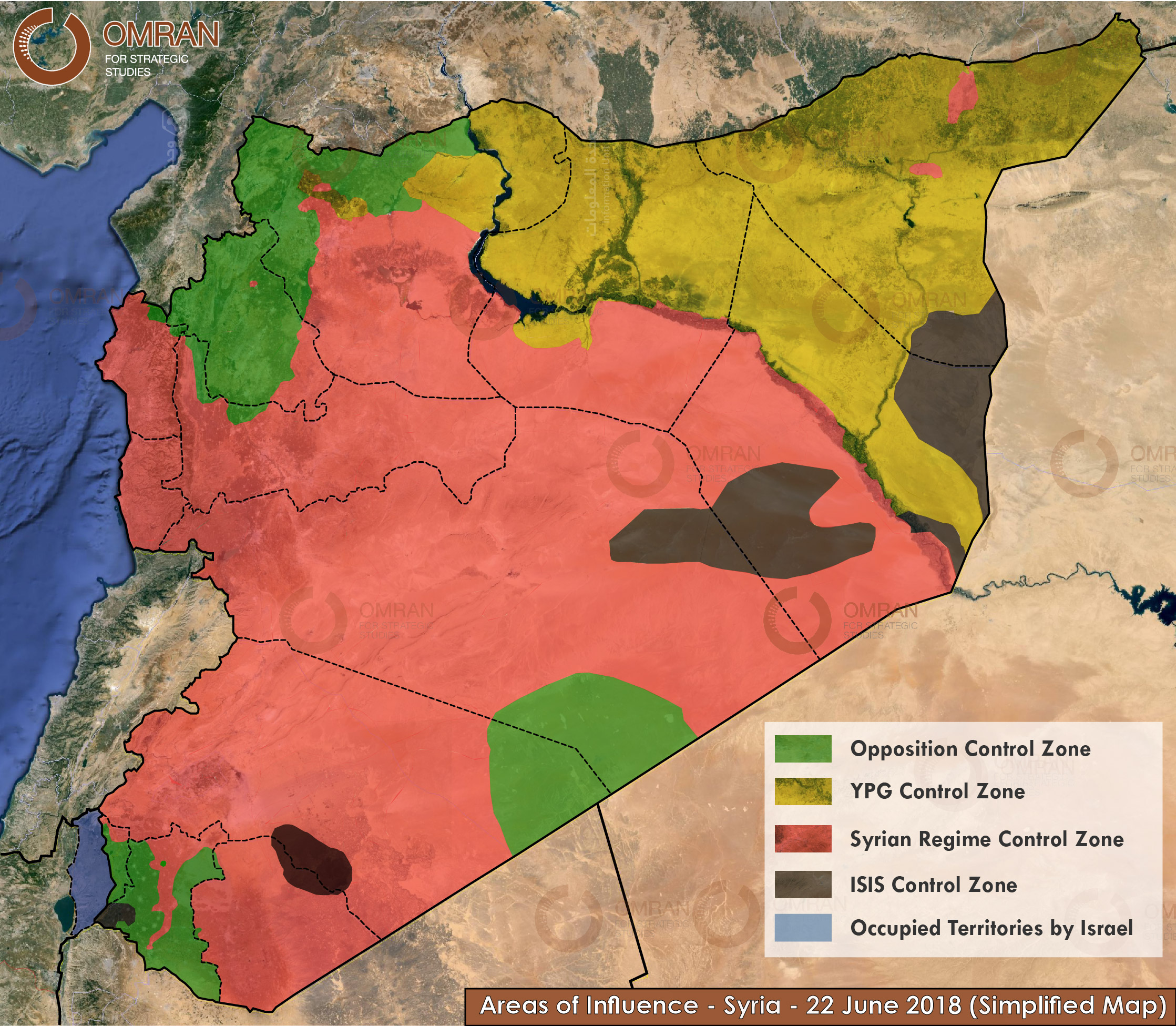

At the same time as these political changes were happening, the areas of influence and control on the ground were consolidated in 2018 into the north and northwestern portion under Turkish control, the northeast under the U.S. and SDF control, and southwestern Syria under the influence of the U.S. and Jordan, allowing Israel to strike any sites that it deems threatening. The areas of siege and opposition group control have been eliminated. International and regional influence has thus become more distinct, as efforts to control and integrate both armed opposition and pro-government groups continue.

This new phase is characterized by a complex series of partial deals that build on one another, and the arrangements among the state actors are developing in a "step by step" policy approach. The "counter-terrorism" framework that was used to justify the entry of these countries into Syria, is no longer a justification for their continued presence and influence: the U.S. is increasingly focused on the "Iranian threat;" Turkey is focused on "fighting the PKK" and security its borders; Israel justifies its interventions with the need to protect its borders against the "Iranian threat" and to prevent the transfer of weapons and fighters toward its borders; and Jordan is now also interested in protecting itself against the “Shi’ite crescent".

In light of this new landscape, contributing writers to this book discuss several aspects of Syria's current form of governance and how experiences on the ground in the different areas of influence converge or diverge from the concepts of centralization and decentralization, both vertically and horizontally. Towards this end, the chapters of this book first clarify the concepts and forms of decentralization and the way they are applied in post-conflict countries. They highlight the important role that agreeing on the form of governance and power sharing is an important factor in maintaining territorial unity and in shepherding negotiations to a more relevant stage of the new post-conflict reality. Next, the authors delineate decentralization in terms of its political, security, financial, and developmental functions, and review the constitutional and legal foundations of administrative and political decentralization in Syria. Finally, the authors present the experiences and applications of governance since 2011 in the regime-controlled areas and opposition-controlled areas, as well as in the SDF-controlled in northeast areas of the Democratic Autonomous Administration. Woven throughout the book are comparative descriptions of the experiences from Iraq, Lebanon, and other countries emerging from conflict, to see what lessons can be learned from the ways that these countries have negotiated the distribution of powers between central and local administrative units.

This book aims to help lay out a path towards the restoration of the legitimacy lost by all parties in Syria through the organization of local governance tools based on the experience of local councils. Local councils have tended neither towards excessive forms of decentralization nor to authoritarian centralization, but have instead followed a path that strengthens local structures and sets limits to central state authorities by granting powers rather than delegating them. At this stage, it is essential to work in parallel on strengthening the central government while also safeguarding and reinforcing the gains of the local councils through constitutional guarantees and a new local governance law. This book also stems from recognition of the need to shift away from limited centralized negotiations among the two “sides of the conflict” through a constitutional process followed by general elections, towards a negotiation based on power-sharing arrangements. Local governing bodies and other local actors should be engaged in the process of deciding which functions and authorities are mandated to the central institution versus the local governing units.

The chapters of this book were contributed by several researchers who differ in their approaches, but they all agree on the need to develop a decentralized Syrian model that avoids the reductive binary approach of political decentralization / administrative decentralization or federalism, and one that is based on the sharing of powers and functions, thus transitioning Syria’s system of governance from local administration to local governance. There is no doubt that further development and discussion of these ideas is required, but we present this effort as a starting place for a dialogue in the Syrian community on the most authentic or locally developed form of governance for Syria, which after years of adhoc decentralization, has become more localized than ever before.

Finally, it is important to note that most chapters were written in late 2017 and early 2018, which was before the change of control of Damascus suburb, northern Homs and the southern front. The arguments for a tailored and customized Syria-centric decentralization model put forth are still valid regardless of the controlling armed party.

Executive Summary

Chapter one of the book focuses on the concept of decentralization and illustrates the differences among countries when it comes to choosing how they exercise administrative authority. Every country’s approach to governance is influenced by its political and social conditions, as well as the maturity and depth of its democratic practices. The need to shift towards a decentralized system becomes apparent after examining factors related to a state’s nature, size, and degree of political stability. Decentralization becomes a necessity for stability in some countries because of its core idea: the distribution of power and functions of state institutions between the central governments and local administrative units. This conceptualization reaffirms the fact that the transformation to fully decentralized system may be risky for many governments, despite the promise that decentralization holds as the solution for most conflicts in developing countries such as those in the Arab world. Chief among these problems is the need to expand the political and economic participation of citizens. Still, given the ethnic and sectarian diversity and complex nature of countries, decentralization can be a threat to state unity.

Chapter two describes political functions of the state in a decentralized system and how it is practiced in different versions of decentralization. Political functions of the state take many forms depending on the degree of decentralization and mode of local governance. The far end of a decentralized governance system continuum appears in the practice of full political decentralization (full federalism), where provinces and regions have their individual constitutions and laws, exercise special legislative, executive, and judicial powers, and influence federal government policy through a political oversight authority and through their representatives in the legislative branch councils. Local governments, meanwhile, exercise specific roles in these functions under the partial political decentralization within their constitutionally-vested authority. These roles are primarily related to domestic policy-making and the development of local rules and regulations that do not contradict federal legislations. In administrative decentralization modes of governance, the practice of political functions and duties is reduced to a great extent as it focusses exclusively on administrative and executive functions of local governing institutions. Local administrative units would then be fully subordinated and controlled by the central administration in the capital. In partial administrative decentralization modes of local governance, political functions completely disappear from local units.

According to chapter three of this book, the exercise of legislative and judicial functions within a decentralized system will require reforms in the Syrian judicial branch, such as: the restructuring of the Supreme Judicial Council to ban the executive branch from holding membership in it and stop its interference, and the repeal of laws that encroach on public rights and freedoms with judicial not executive branch oversight. Assessing the current form and content of the Syrian Constitution in terms of centralized or decentralized approaches highlights centralism as highly visible and grants authority to the presidency (which has broad constitutional powers) to override all other authorities and functions of the state. Instead, the principles of separation and distribution of powers should be applied to three independent bodies in order to create balance and cooperation between them. With regard to legislative duties in Syria, this paper shows that the Constitution has broadly granted legislative duties to the People's Council of Syria (Parliament) and the President of the Republic, transforming the mandate of the Parliament from drafting laws to ratification of presidential laws. Reforming this imbalanced structure requires redefining the scope and mandate of the Parliament, abolishing the broad powers granted to the President, and reducing the centrality of legislation process and parliament. There needs to be a shift toward some kind of decentralization that divides future legislative functions in a balanced approach between the exclusive jurisdiction of the legislative branch, and the jurisdiction of the executive branch for all that is not stated in text of the constitution.

The fourth chapter focuses on security functions in decentralized systems. In the context of conflict-ridden or post-conflict countries, it is critical and necessary to re-assess national security functions: their applications, mechanisms for implementation and governance, and how security roles are distributed at different levels of government. This paper emphasizes that the redistribution of security duties and authorities in decentralized countries (in accordance with the lessons from stable and unstable countries) may result in a more efficient and coherent security architecture depending on who and how such a process is executed and whether by means of national actors, cross boarder actors, or international actors. In the search for a governing framework of the Syrian security sector within a decentralized system, independent intelligence agencies should have a clear mandate of intelligence gathering only (except for police forces and anti terrorism units that can arrest citizens) and an identified geographical jurisdiction. Local governing bodies should be constitutionally mandated to provide local security services and conduct police functions and duties locally. The assessment and identification of security threats and risks and the counter strategy to such risks should be developed locally and shared with central agencies for coordination.

The fifth chapter highlights the dialectical relationship between decentralization and its role in local development in countries emerging from conflict. Local development is one of the most important determining factors in whether or not decentralization is adopted in these cases. While some of post-conflict countries have reached acceptable rates of economic and social development after moving to a decentralized system, others have not. This disparity may be due to factors linked to each country’s particular local development process and adopted form of decentralization. This paper emphasizes that in the context of the Syrian situation, the country has suffered from the absence of a clear developmental model for decades. This has led to major developmental imbalances at the central state level, which are most evident in the developmental disparities between Syrian governorates. The adoption of a model of administrative decentralization in Syria will help to mitigate this disparity by empower local communities to participate in the local development process.

The sixth chapter, which deals with financial decentralization, emphasizes the fact that the successful implementation of decentralized systems of government in post-conflict countries depends largely on their ability to establish regulatory frameworks for financial decentralization and mechanisms for the collection, distribution, and disbursement of financial resources at various levels of government and administration. Successful implementation also requires substantial reforms in fiscal policy in general and in spending policies in particular. This paper finds that that the model for allocating financial resources to the local administrative units out of the state budget in Syria has many flaws. It is necessary to grant administrative units greater financial independence and to define metrics for successful financial decentralization to measure whether these units are meeting developmental requirements and making effective contributions to economic and social stability in their regions.

The seventh chapter examines the reality of local administration in regime-controlled areas. It illustrates the dominance of the central government in the local administration systems in regime-controlled areas, the growing influence of the Baath party, and the increasing influence of local Iran-backed forces in the operations of some local administrative units. This paper finds that the service sector crises in the areas of local administration units are indicative of their lack of funding, dysfunctional mechanisms, and insufficient personnel, forcing them to rely on the central government to conduct their affairs. It also argues that the regime is not interested in decentralization – which runs counter to its desire to retain centralized control – but it does use decentralization politically as a bargaining chip for negotiations with the international community, particularly the Europeans. The regime also attempted to manipulate the boundaries of the electoral constituency of administrative units to change administrative districts and weaken opposition areas by preventing them from winning elections in their areas while rewarding loyalists.

The eighth chapter focuses on the reality of governance in Syrian opposition-controlled areas. It reaches several conclusions, the most important of which is that local councils have undergone changes in terms of structure, mechanisms of formation, and function, as their organizational structures have stabilized and they rely increasingly on the elections for their membership. They have also been able to consolidate their service roles, compared to their role in local security and politics. The financial file is one of the primary challenges facing local councils as they cope with growing financial deficits, due both to the nature of revenues and expenditures, and also their lack of financial systems or laws regulating their budgets. This chapter explains how the long duration of the conflict, the transformations in its nature, the push towards coexistence, and the survival of the regime have all stimulated competition between local actors, of which the local councils were one of the most prominent players due to their political value and local legitimacy. As a result of the way the local councils have dealt with these challenges and threats, they face one of three scenarios in the foreseeable future: vanishing entirely, forming regional or cross-regional self-administrations, or continuing the current independent local units structures.

The ninth chapter analyzes the reality of governance in the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. It shows that lack of transparency is a key feature of service delivery, financial administration, and the management of strategic resources within the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. The process of forming legislative councils (mandated to pass laws) in these areas was based on partisan consensus that relied primarily on the literature and system of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM). Laws passed by these legislative councils, such as laws related to self-defense, changes to school curricula, and civil status laws, are problematic. A review of the structure of the DAA and its legislative and executive bodies, shows the presence of a partisan political project that is being forced on the local population through its security and military apparatuses. This paper concludes that the DAA, though able to impose a unique governance model, still suffers from problems of representation, legitimacy within its population, and a lack of competent personnel, and it has failed to eliminate the local and regional concerns arising from this project.

The tenth and final chapter of this book proposes a unique Syria-customized decentralized framework, one that takes into account the importance of achieving stability. It highlights the importance of refocusing international negotiations on two parallel tracks: negotiations policies to strengthen central state institutions in order to create conditions for peace and stability, and empowering local governance models through local negotiations on power sharing of authorities and functions of the central state with local administrative units. They must also revisit the basic Geneva Communiqué according to the principle of power sharing agreements between the center and periphery and not only a central agreement where the opposition and regime share authority. This means prioritizing internationally-monitored elections over any other track, beginning with local administration elections.

In order to ensure the success of the elections, essential actions are required from the different parties with regards to the restoration of the functionality of police and local courts. It is therefore necessary to begin drafting a new law for local administration (decentralization) to allow locally-elected authorities to have full control over the work of the police and administration of local courts.

The opportunity exists for local councils to legitimize their structures and negotiate new authorities, guaranteeing a decentralized model that provides expanded authorities to the councils and governorates, based on the strength of their electoral legitimacy. This chapter emphasizes the need to empower the tools and foundations of local governance both constitutionally and legally, and to ensure that the countries with a presence on Syrian soil help push the negotiations to a peace-building stage and guarantee relative stability on the ground until an agreement on the various security arrangements is concluded.

for More Click Here: http://bit.ly/2B2Vxqd

Navvar Saban "Oliver": "There is no final agreement and no final disagreement"

Navvar Saban "Oliver", the Information Unit manager at Omran Center, recent interview entitled "Battle for Syria's last major rebel bastion on hold as Putin and Erdogan meet to discuss next moves" by Borzou Daragahi, published in the Independent

“There are 12 observation points were equipped with limited military equipment and their main role was to monitor the agreement done in Astana. at the moment when the regime started to mobilise its forces around Idlib, Turkey started to send reinforcements to some of these points.”

he also added the follwing , for the second week in a row, thousands of Syrians in the province took to the streets in peaceful, colourful demonstrations that recalled the first months of the 2011 uprising against the Assad family’s decades-long dictatorship. “For the time being, everything is postponed,” at the end he said. (There is no final agreement and no final disagreement.)

Independen: thttps://goo.gl/QxMjgt

Dr. Ammar Kahf, Commented on latest developments in southern Syria

On the 25th of July, Dr. Ammar Kahf, the executive director of the Omran, commented on latest developments in southern Syria to USA Today, by stating that the regime’s territorial gains in Daraa has put Iran and Hezbollah closer to being a threat to Israel and regional powers.

This development will increase the likelihood of greater conflict in the Middle East. Developments in Daraa are also signs of a new era in the Syrian conflict, where domestic actors have largely disappeared and given way to international and non-state actors using Syria for their own agenda.

Dr. Kahf has stated that “The story of the armed Syrian opposition is over, Iran and Hezbollah are much stronger today than a month ago and closer to the southern front. I think this (Syrian conflict) will continue to escalate.”

Special thanks to the co-writers of the Article, Jacob Wirtschafter and Gilgamesh Nabeel.

Source: https://usat.ly/2NPpBc6

The Autonomous Administration in Northern Syria: Questions of Legitimacy and Identity

Executive Summary

- The Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) project faces a number of challenges, including repeated failed attempts at gaining legitimacy and recognition by different actors within the Syrian conflict. Despite the success of the DAA’s military wing—the People’s Protection Units (YPG)—in fighting the so-called Islamic State group (ISIS) and becoming America’s main ally on the ground for the international coalition; their alliance with the US did not gain them additional political recognition. Nor did it protect them from parties to the conflict such as Turkey that view their project as a major threat, in response to which it launched Operation Olive Branch. The Assad regime in Damascus also views them as a threat to its national sovereignty and threatened to wage a non-stop war on areas under control of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and to push for public uprising and protests against them in Raqqa, Manbij, and Hasaka.

- The DAA has been unable to garner support from the local communities under its control, both Arab and Kurdish populations, for a number of reasons including their lack of a clear identity. On one hand, the DAA is “Kurdish-centric when needed,” and on the other hand, it preaches a “Democratic Nation Theory” that transcends ethnicity and religion. This is reflected in the “Social Contract,” it imposes, which contains some concepts that can be regarded as general Syrian demands after years of war and killing, such as the idea of strengthening local governance and decentralizing power. But at the same time the “Social Contract” details a number of concepts that overstep central state authority, and alter local social norms and practices based on a partisan ideological background.

- Difficulties in implementing the “Social Contract” and a new political program in different geographical regions of Syria with a variety of ethnic, cultural, and religious identities, resulted in a number of conflicts within the SDF alliance on several occasions.([1]) Furthermore, the Democratic Union Party (PYD) was unable to convince the majority of the Kurdish public to adopt the DAA project either. Despite their security grip on the DAA areas, there have been several protests held by the Kurdish National Council (KNC), criticizing various issues such as the forced implementation of Kurdish as the only language used in schools in Kurdish majority areas.

- In terms of resource management, the DAA’s governance suffers a lack of transparency with respect to its mechanisms for managing institutional income expenditures. DAA’s assets are administered by the Executive Committee of the cantons, which act in place of typical government ministries and operate independently. Despite the relative stability in large areas under DAA control, they have not successfully achieved a level of administration that is proportionate to the amount of resources and assets available to them.

- Despite having characteristics of a functioning governance system, the DAA still suffers from a number of key deficiencies, notably: a lack of transparency and clarity, the absence of a clear strategic plan or set of policies, the marginalization of civil society, a lack of bureaucratic and technocratic expertise.

Introduction

The Syrian Revolution created conditions that allowed non-state actors to emerge across the Syrian map including the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its umbrella, the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM), which together along with other smaller parties established the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA). From mid-2012 until present day, the PYD tried to keep feet in both camps (to remain neutral – supporting neither the regime nor the opposition) while working to strengthen its own project. The DAA project went through a number of phases, from times of relative stability to times like the battle for Kobani in January 2015. They continued to gain power and territory until Turkey launched Operation Olive Branch, which resulted in the DAA losing Afrin, one of its most critical cantons.

During the development of the DAA, challenges arose at the political, legal, executive, and administrative levels, operations and take away from its legitimacy to govern. These issues are explained at length in this analytical paper.

The DAA: Acceptance and Recognition

The DAA originated—and emerged from its dominant group, the PYD—in a political and social context in which people were looking to undermine the legitimacy of the Assad regime in all its forms. The main political force, the Democratic Union Party (PYD as a party formed at 2004), comes from within the DAA itself. They existed in a political reality in which people were looking to discredit any legitimacy for the Assad regime. The DAA failed to get any guarantees during its fight against ISIS that would safeguard its political gains afterwards. Despite the PYD’s extensive efforts to stabilize its project, the DAA still suffers from a lack of recognition from key actors: first from a large slice of its primary constituency the Kurds; second, from the Assad regime; and finally, Syrian opposition groups differ in their evaluation of the DAA, some because of their differing standards of local administration and others due to their regional alliances.

There are three identifiable sources of legitimacy in Syria today: the Syrian people and their cultural and political activity; the regime, due to the international community’s continued recognition of the Assad government as the Syrian state; and the Syrian opposition due to the international community’s recognition of its coalition institutions. The DAA will continue to suffer from a lack of legitimacy if it does not secure recognition from one or all of these sources.

On a local “Kurdish” level, the DAA’s legitimacy is contingent on a number of factors, the most important of which is the success of its security operations in keeping armed conflict out of urban areas under its control. Other factors include its success in the fight against terrorism, and its ability to delay Turkish intervention deeper into DAA territory. The DAA has been able to effectively use these issues in developing its political narrative, often exploiting developments in the situation of Kurds in Iraq and Turkey. For example, the PYD used the fighting against Turkish army in Kurdish populated Turkish cities in 2016 to spread fear among the public by broadcasting details of the fighting through the DAA’s media channels. Promoting an “external threat against the Kurds” narrative in its political rhetoric has been a key strategy for the DAA since it first took control of territory in northern Syria. The fear of instability is one of the most important reasons that the population continues to overlook other practices, in some cases human rights violations, by the DAA.

With the end of ISIS’s military power in sight, there is a growing need for the DAA to gain legitimacy in a the eyes of much larger cohort of non-Kurdish Syrians, especially after taking control of places like Raqqa and rural Deir Ezzor. The events of Manbij City, with increasing calls for protest against “Kurdish” control of the city, have revealed the size of the imbalance between security and local support. Recent assassination attempts in Manbij targeting the DAA’s civil and military leaders, including members of the US-led international coalition, highlight the local population’s low tolerance for DAA practices.([2]) It is worth noting that the regime has tried to capitalize on these negative sentiments towards the DAA and reintroduce itself as the legitimate governance structure northeast of the Euphrates River. The regime has funded and supported Hussam Katerji, a local businessman and Member of the People’s Assembly, to form the so-called “Popular Resistance in Raqqa,” with the stated goal of ending what it refers to as the American occupation. The group has called on locals in Raqqa to protest in support of Assad and to demand that the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and others coordinating with the US-led international coalition leave the city.([3])

Internationally, the PYD has worked hard to gain recognition from three key stakeholders: Russia, the United States, and some EU member states. The PYD traditionally enjoyed strong ties with Moscow due to the historic relationship between the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) and the Soviet Union, but made recent efforts to get closer to Washington for a number of reasons. The most important of these was to hinder a Turkish intervention, especially as they approached the brink of armed confrontation with the Turkish military. The PYD’s relationship with the US began during the siege of Kobani, and later developed into a partnership on the ground fighting ISIS. The People’s Protection Units (YPG) succeeded in convincing the Pentagon to depend on them exclusively by quickly adapting to America’s regional priorities. This was facilitated by the Syrian opposition’s insistence on fighting both the Assad regime and ISIS simultaneously, an approach that Washington rejected, arguing that it did not want to be distracted from critical anti-terror operations.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) was eager to work with the YPG, but put pressure on them to merge into a new group called the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in order to avoid potential legal issues due to the designation of PKK as a terrorist organization by the US. The SDF’s literature does not refer to any ideological affiliation with the PKK and does not preclude Arabs or other non-Kurdish people from joining. Instead, the SDF actually encouraged Arab armed groups to join them in full, with their fighters and equipment, in order to show their ethnic and political diversity makeup of the new formation at the behest of the Americans. Regardless, the new group and its all of its subsequent mergers maintained a framework dominated by the YPG, which controls all decision-making mechanisms and power structures within the SDF.

Despite the flexibility towards the American demands demonstrated by the PYD’s leadership in Qandil ( The PKK has bases in the Qandil mountain area of Iraq([4])) and at the local level in Syria, their relationship with Washington remained limited to military cooperation between the SDF and the international coalition, without translating to any sort of political recognition. Instead, the Americans put significant political pressure on the PYD leadership to break ties with Qandil. This culminated in the creation of the new “Future Syria” party as an ideological partner to the SDF without direct connection to the PKK or related institutions.

The lack of US political recognition of the DAA in Syria pushed it to keep some remnants of positive relations with both Tehran and Damascus, and to maintain their historic relations with Moscow. Russia recognized the DAA’s interests in pursuing relations with Russia despite its military coordination with the US. The DAA’s relations with the US did not deter Russia from using the DAA to serve its own political agenda in Syria. Russia allowed the DAA to open a representative office in Moscow, and invited the group to participate in international forums and negotiations for a peaceful political solution. Russia also used its unique relationship with the DAA to put pressure on both Turkey and the United States at certain times of the conflict. Russian political recognition of the DAA was coupled with security cooperation after Russia’s military intervention in Syria. They supported YPG offensives to take control of Tel Rif’at, Menagh Airbase, and other villages in northern Aleppo, and sent Russian military detachments to serve as a buffer zone in Afrin. Ultimately, Russian interests came to align more closely with Turkish security priorities, especially in Operation Euphrates Shield and Operation Olive Branch, which were both results of military and security arrangements made during the Astana process.

The DAA’s relationship with EU member states offered them opportunities to open political missions in a number of European capitals including Brussels, Stockholm, Paris, and Berlin. These missions do not have official political recognition from their host countries and their legal presence is limited to registration as non-governmental organizations. However, these missions are directly managed and operated by PYD representatives.

As described above, despite its political and military maneuvering, the DAA was unable to overcome the obstacle it faces in gaining societal, national, and international acceptance and recognition. In reality, its activities did not extend beyond portraying a façade of a formal structure with little space for local participation. On a national level, the two sides of the conflict—both the regime and the opposition—have hostile relations with the DAA until today. On an international level, the changing political context and its impact on the political process means that behavioral shifts are a key characteristic of the actors. For this reason, any legitimacy or recognition the DAA attains is temporary and could change at any moment.

A Social Contract in a Fluid Political and Military Context

A group of parties affiliated with TEV-DEM, and several other related organizations, together announced the formation of the DAA on January 21, 2014.([5]) The announcement followed a series of failed meetings and attempts to form the Council of Western Kurdistan, negotiated in Erbil.([6]) The DAA announced a special social contract, which would act as the foundation of a constitution. Later on, this social contract became the cornerstone of “The Social Contract of the Democratic Federation of Rojava – Northern Syria,” a DAA project that evolved from the Syrian Democratic Council that was formed on October 12, 2015. A draft of the social contract for the federation was circulated June 28, 2016 in the city of Malkiyeh. The document was approved by the DAA’s Constituent Assembly on December 29, 2016, under the name “The Social Contract of the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (DFNS),” after the word “Rojava” was removed from the title. The “Social Contract” document raises a number of challenges related to legitimacy, including questions surrounding the political representation of key actors of northern Syria, issues related to the absence of a capacity to measure popular support, the absence of approval of the “Social Contract” from the Syrian central government or any other government.

The “Social Contract” does not specify the borders of the DFNS. Instead, the text of the preamble refers to a “geographic concept, and political and administrative decentralization within a unified Syria.” The concept of political decentralization is unclear and vague, and the text appears to confuse the concepts of the rights of entities within a confederation —which is more like a union of sovereign states—and federalism, which is a looser term that cannot be defined by one particular model.([7])

Through its new constitution, the DAA granted itself authorities of a central government. In article 22 of the DAA’s “Social Contract”, it not only recognized the right of self-determination, but also appointed itself as the executor of this right without a national agreement with other components in specifically northeast Syria or other parts. Additionally, it contradicts itself when it recognizes the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Syria and at the same time unilaterally declares the right of self-determination to all groups and components of Syria. Articles 54 to 84 describe the governance structures and institutions of the DFNS starting with the smallest structure—the commune—all the way to the committees and executive councils of the cantons, as well as the executive council of the DFNS. The same articles explain how the councils and committees are formed, including the election commission and the defense council. The Executive Committees of the cantons includes 16 offices and the Executive Committee of the DFNS has 18 general councils. The total number reaches 33 executive bodies without taking into account the neighborhood councils. Despite the fact that the “Social Contract” stresses principles of democracy and freedom, it created a fertile ground for local dictatorship and a crippling bureaucracy by obligating all citizens to serve in at least one neighborhood commune office.

Article 66 states that “every region can develop and strengthen its own diplomatic, economic, social, and cultural relations with the neighboring people and countries, provided they do not contradict with the ‘Social Contract’ of the DFNS or with the Syrian state.”([8]) Yet, the DAA has itself opened offices and developed relationships, including the opening of foreign missions, as an effort to secure its political interests. Interestingly, hosting foreign militaries in a territory is an act usually undertaken by a formal state, and is therefore incompatible with Article 66. In response to such criticisms, the Co-President of the Council of the Federation of Northern Syria, Hadia Yousef, said during a presentation at the Kurdish Center in Egypt on July 20, 2016 that:

- The federal system detailed in the document does not call for the division of or separation of northern Syria, instead we accept to live in a state that protects the rights of the people who live in it.

- Federalism is the only solution to the Syrian issue, and if they desired to separate, they would have already done so.

- Defense and foreign policy will be managed by the central power.([9])

The “Social Contract” of the Federation of Northern Syria faces a number of complex challenges, especially as it expands. There continues to be a lack of representation of the KNC as well as the residents of Raqqa, Manbij, southern rural Hasaka, and Shadadi, all cities that have a majority Arab ethnic makeup. There is also the issue of unilaterally adopting the federal model without consulting other political components in the country, and doing so during a period of political and military fluidity and with increased regional and international intervention.([10])

Administration of Social and Geographic Diversity

Since the start of the Syrian revolution, the PYD (DAA) controlled different and diverse geographic territory in which people from a variety of backgrounds live. Between 2012 and 2015, they had control of 12% of Syrian territory including Afrin, Kobani, and two thirds of Hasaka province.

The area of Afrin, located in the larger Akrad Mountains region,([11]) has plentiful fresh water, fertile mountainous terrain, and strong olive and textiles manufacturing and trade industries. Most of the area’s residents are Kurdish and unaffiliated with tribes. Al-Jazira and Kobani on the other hand, lie on flat plains and are known for their dependence on wheat and cotton cultivation. These two regions suffered from marginalization by the Assad regime as well as a stifling of the private sector. The main cities there are also relatively young, founded at the turn of the last century after demarcation of the current borders between Syria and Turkey.([12])

In addition to the impacts of economic and commercial activity on the social structure and ideological orientation of the cantons, there are other social and political differences within the DAA areas. For example, Afrin’s close proximity to Aleppo is one of the reasons that it had a strong manufacturing sector and an abundance of factories. The manufacturing and commerce-based social structures of Aleppo have also had an influence on Afrin, helping create more stable social dynamics than in the al-Jazira and Kobani regions, which depend more on seasonal crops. The level of attachment to a specific geography is dependent on natural factors. For example, olive trees in Afrin are hundreds of years old, whereas al-Jazira and Kobani were pastoral lands for the inhabitants of nearby cities just 100 years ago – with the exception of historic cities like Amude and Malkiyeh. For the reasons, settlement patterns east of the Euphrates River are different from Afrin. For example, one of the main reasons for the migration of 1.5 million people from al-Jazira to Aleppo and Damascus between 2006 and 2008 was the lack of rainfall.

The diverse make up of these three regions (al-Jazira, Kobani, and Afrin) also affects the political and partisan identities there, as a result of several factors. First, they are influenced by significant Arab cities nearby. Despite high numbers of Kurdish residents in Kobani and Afrin compared to northern al-Jazira, Kurdish nationalism first appeared in full force in Hasaka province in response to the Baath Party’s nationalistic and exploitative policies. Looking closely at the geographic distribution of the political forces in Malkiyeh near the Iraqi border in the east, all the way west to Afrin on the Syrian-Turkish border, it is clear that there are large differences even among the Kurdish political factions themselves. The strongest grassroots support for the Iraqi Kurdistan National Party (KDP) is concentrated in the east, and the PKK’s support base gets stronger towards the west, culminating in their strongest bastion of support in Afrin. Furthermore, the residents of al-Jazira still hold strong tribal affiliations, while this practice is less prominent in Afrin and Kobani.

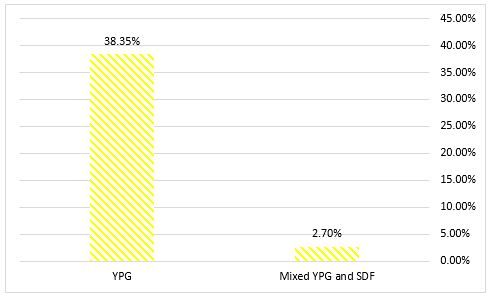

The YPG’s territorial control expanded with the creation of SDF in mid-2015, reaching 24% of Syria’s total territory, more than double the area previously under their control. This increase in territory also significantly increased the number of people as well as the types of cities, towns and villages under the DAA’s control. After having only controlled areas with predominantly Kurdish populations initially, the DAA found itself in control of an area that spread from Kobani in the north, through Raqqa and rural Deir Ezzor, reaching the Iraqi border in the south at Albu Kamal, and from Manbij in the west through Tal Abyad, reaching Malkiyeh in the east. This geographic area is characterized by small Arab cities and towns, vast desert plains, and numerous small hills and villages. The number of inhabitants under the DAA’s control increased from two million to 3.5 million according to some estimates. This also resulted in significantly increased costs related to efforts to protect these territories and people from attacks by ISIS.([13])

The impacts of this geographical expansion on the DAA and its related military and political bodies were not limited to the larger size and higher number of residents. This expansion into southern parts of northern Syria added new Arab elements that the DAA had not dealt with in its initial phase, from 2013 to mid-2015.

The Euphrates River Basin is known to have a large Arab population that still largely retains its tribal traditions. Before the battles for Raqqa and rural Deir Ezzor, the DAA depended on the Kurdish forces as fighters and administrators, and used Kurdish slogans and worldviews to recruit fighters and leaders. This was the most sensitive and volatile issue defining relations between the DAA and the Arab elements coming from a variety of backgrounds and alliances. The Arab tribes in the Euphrates River Valley region in particular have very specific and unique traditions that are unfamiliar to Kurdish members of the DAA. This demographic and social diversity forced the PYD to adopt the idea of a “democratic nation” as a broader worldview in its initial stages, instead of its traditional ethnocentric nationalist worldview. However, this worldview carries with it a number of contradictions to the tribal traditions in the Arab areas, forcing the PYD to constantly reinterpret and redefine their political project according to the orientations of the variety of social groups under their control.

These ideological, political, partisan, and ethnic differences raise the question of the extent to which the idea of a “democratic nation” is influenced by the varied origins of the people living under the DAA. The PYD presented this worldview as a comprehensive solution to achieve justice, equality, and brotherhood for all the people of the east. So what exactly is the “democratic nation,” where did it come from, who suggested it, and how will its problems be solved?

The “democratic nation” as the theoretical basis for the DAA

The “democratic nation” worldview was not created by the DAA. Instead, it is rooted in the evolution of the theory of anarchism by the American thinkers Murray Bookchin and Naom Chomsky. They re-framed anarchism within the existing state structures in a manner that preserves its institutions to avoid total chaos in the absence of governing alternatives. The two thinkers attempted to restrain concepts of anarchism and socialism to recognize the existence and reality of the state in its current framework and then launch its struggle to change this reality away from the workers revolution or the return to natural life.([14])

The PYD describes the “democratic nation” as: “a group of people connected by common ties who practice of democracy to govern themselves.”([15]) Here “democracy” is not used as a governance system and instead as a description for a group of people. This contradicts the Islamic and modern social concepts that adopt religion and nationalism respectively to define the nation’s borders. This understanding is attributable to the socialist and communist rooted traditions of the PKK. After he was arrested, Abdullah Öcalan engaged in revisions to his worldview, and adopted this “democratic nation” concept as a new ideology for his party and followers. In his revisions, Öcalan criticizes previous attempts by himself and the PKK to create a Kurdish state according to modern standards. He developed the concept of the “democratic nation” after an intellectual journey, studying the most significant cultures, religions, and governance structures that existed in the past and today.([16])

The PKK’s members and supporters adopted the “democratic nation” worldview as a roadmap to the “brotherhood of people,” and a key to addressing the problems of the modern nation state. They criticize Marxism and socialism for stopping at dividing society up into competing classes, while its model failed to govern when faced with the capitalist system, which monopolized manufacturing and science and put them under international control in direct violation and oppression of people’s rights. Supporters of the “democratic nation” believe that continued studies and revelations about the shortcomings of past ideologies and philosophies are required in order to develop a new philosophical basis on which to revive critical efforts to deal with the effects of modernization and capitalism.

Öcalan developed the “democratic nation” concept in his early years of captivity. The application of his worldview went into effect in 2003 when alternative local structures emerged to take the place of the central administration of his party. This happened first in order to take the pressure off of his supporters and as a shift away from a Marxist-socialist model towards the model of a “democratic nation.” In terms of application, this approach attempts to enforce the principle of a people’s confederation by shifting central powers away from an authoritarian nationalistic state that gets its legitimacy from external powers. In regard to Kurdistan, its liberation is achieved through the liberation of the Kurdish people. This change does not generate freedom, but rather awareness and revolutionary thinking as the basis of a free society.([17])

Yusuf al-Khaldi, a researcher at the Kurdish Center for Studies, identified two main aspects of the “democratic nation”:

- Local autonomy: This is achieved by allowing local residents to declare their own individual and group identities, with the right to declare themselves as part of a general shared identity capable of representing all the smaller sub-identities as part of the entire nation. Through this reality Kurdish nationalism can transform into an entire nation that shares a semi-independent democratic form.

- General structure: This is achieved by offering widespread freedoms in the diplomatic, legal, social, cultural, and economic sectors within the context of a general state and its borders.

The DAA achieves the principles of semi-democratic independence through two mechanisms:

- An agreement with the nation that controls the modern state apparatus in accordance with a new social contract shared by all aspects and components of society based on their heritage and shared histories in the region, as well as the history of their cultures and relationships.

- The exclusion of any concepts that contain ideas that suggest or refer to policies of integration, dissolution, and exclusion of the other, and complete abandonment of genocidal solutions previously followed by the nation-state which ended in failure. The Kurds should also abandon demands for an independent Kurdish state.

He specifies two ways for the establishment of the “democratic nation”:

- Nationalistic groups should give up their efforts to establish their own states and desire to monopolize the state, and accept a nation state based on semi-democratic independence.

- Kurds should take unilateral steps to move away from trying to establish an ethnocentric nation state and instead adopt the principle of semi-democratic independence.([18])

The philosophical foundations of the “democratic nation” also offer solutions for the problems of women and marriage. According to the theory, the modern capitalist system has failed to understand married life by considering women as the property of men. Instead, the “democratic nation” theory, as opposed to traditional and religious beliefs, views women as productive members of society that are capable of being more productive than men. Addressing women’s problems requires creating a balance in basic tasks and responsibilities in communal life: securing food, safety, and the reproductive process. In the case of the “democratic nation,” the growth of the human population should stop, society must be built between women and men based on "equal life," and gender equality must be fully established.

Resource Management

The reality of the DAA’s rule are further complicated by the lack of transparency of a number of mechanisms related to its resource management and institutional expenditures. The resources available to the DAA are best studied in two phases: the first phase is pre-2015—before they controlled Tal Abyad—and the second phase is from the control of Tal Abyad to present day. Taking control of Tal Abyad brought partial contiguity to the DAA’s territory, connecting the two islands of al-Jazira and Kobani, spanning along the Turkish-Syrian border from Malkiyeh to Manbij. During both phases the nature of the DAA’s resources remained similar:([19])

- Income from public properties: oil and gas in eastern Hasaka province, and grain silos.

- Income from local taxation and customs fees taken at the border crossings.

- Income from service delivery.

- Expats in Iraq and Turkey.

- Local donations.

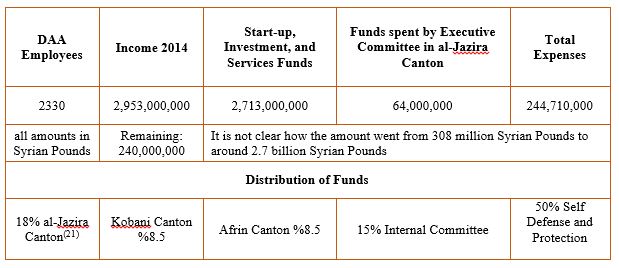

According to Article 53, paragraph 8, of the DAA’s “Social Contract,” the Legislative Committee is responsible for maintaining the administration’s budget. From mid-2012 to 2018 the DAA has publicly shared its finances only once in 2014 and 2015 as part of discussions between the legislative and the executive committees on March 17, 2015.([20]) It is not possible to ascertain the accuracy of the numbers discussed in those meetings. The two budget reports were criticized by members of the councils due to their reliance on lengthy explanations and lack of specific details on revenues and expenditures. The chart below provides details of the DAA’s budget between 2014 and 2015.

It is important here to mention the lack of transparency in oil production and sales, as well as international grants, and the spending of money meant for reconstruction.

Executive Authority

The DAA's finances are managed by an Executive Committee, which was formed at the beginning of 2014. In reality, Executive Committees function in a manner very similar to how sovereign state institutions -such as Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Defense- operate. It extends its legal mandate from the DAA's “Social Contract” and laws passed by the Legislative Committee. From the start of the DAA, TEV-DEM and the PYD both tried to build the Executive Committee on the basis of alliances, creating a coalition-like structure involving a large number of organizations, including those directly linked to them, or allied groups such as the National Arab Committee and the Assyrian Union Party, and other Kurdish, Arab, and Assyrian groups. The PYD tried to monopolize public opinion through these alliances by insisting on commitment to the concept of the "democratic nation." There are 16 Executive Committees in al-Jazira canton, formed by integrating a number of previously existing offices and committees. A study of these facts reveals that there are efforts to present the administrative structures as complete when there are actually serious deficiencies in cadres and their ability to carry out work on the ground, in proportion to the significant territory that the DAA controls.

The Environment and Municipalities Committee tops the list as the most active body in the DAA. The municipalities are mainly tasked with executing a number of projects through their technical and service departments, including:

- Paving of roads inside the cities and the road connecting rural areas with the cities through anonymous bidding. Several tenders are listed in favor of the Zagros Public Roads and Bridges Company, established in 2013.

- Clearing drainage systems and distributing diesel fuel. Distribution of fuel causes tension with many residents due to feelings of preferential treatment and the small amount of fuel provided.

- Establishing city plans for expanding urban areas under their control. Among these efforts was the planning of an industrial zone in Malkiyeh, aimed at keeping the city clean and free of pollutants. The price of a store in the new area was posted as 2.5 to 3 million Syrian Pounds (USD $5500-$6700) depending on the size. Most of the small to medium manufacturers suffered as a result of this decision because they were forced to relocate their shops that they owned to the new location that was unaffordable.Some local manufacturers claim that some businessmen bought all of the real estate in the industrial zone and they now control the prices.([22])

Through taxation, the municipalities bring in large amounts of money for the different services they provide.([23]) They prepare slaughter lots and markets where livestock can be sold, and they tax storeowners for providing protection, cleaning, sidewalk maintenance, and other services. The municipalities suffer from a lack of skilled workers with expertise in city planning, development, and law. Furthermore, the municipalities do not have branches in the Arab areas under DAA control.

The DAA places additional focus on the Education and Development Committee through the passage of a law to change curriculums. The DAA’s control over the education sector was faced with opposition and disagreements by different components of the local population. There is also the issue of the Assad regime retaining control of the main educational institutions. The DAA influences the educational process by paying teacher salaries as well as training and ideological coaching. The seven years of disconnect from a central government, with little hope of reaching a political solution, allowed the PYD to fill the gap by controlling the content of curriculums taught to children in schools, allowing them to preach the ideals and doctrine of PYD ideology based on the teachings of Abdullah Öcalan.([24])

The DAA’s Health Committee faces the biggest set of hurdles as a result of the war. At the top of their list, they struggle from a lack of qualified medical professionals due to the displacement of doctors outside Syria, and the high costs of securing laboratory and hospital equipment. During the time of ISIS’s siege, there was a shortage in the quality and quantity available in the markets. The Tourism and Antiquities Committee is mainly concerned with preventing destructive activities and artifact smuggling. They also conduct environmental protection and preservation projects. The Arts and Culture Commission struggles to use their local branches, theatres, production and distribution of literature effectively. This commission is responsible for organizing rallies, poems, stories, and books based on the teachings of Abdullah Öcalan, the leader of the PKK.([25]) The Defense Commission is the core of the security and military operations in the DAA. It is working to enforce a mandatory military service rule on everyone born in 1986 or later. Over more than three years, the Commission has taken over 20,000 people into compulsory service.

Despite having characteristics of a functioning governance system, the DAA still suffers from a number of key deficiencies, the most important of which are: transparency, clarity, the lack of a clear strategic plan or set of policies, the marginalization of civil society, and the lack of bureaucratic and technocratic expertise.

Conclusion

A number of factors contributed to the DAA’s ability to extend its control across northern Syria. These include the regime’s retreat from areas with a majority Kurdish population in favor of the PYD and its military wing, the YPG. This created a stable and secure environment in which the PYD was able to strengthen its authority. Following the battle of Kobani, the US-led international coalition also contributed to the DAA’s expansion, helping them take control of 24% of Syrian territory. It had previously controlled less than 10% of Syrian territory before joining the US-led international coalition as their partner in the fight against ISIS in Syria. The PYD’s dominance of the military and security sector compared to the other Kurdish parties also contributed to its ability assert its control over the population. The YPG assisted in this by breaking up the armed groups formed by other Kurdish parties, and enforcing strict policies to ensure that there were no competing forces, using the argument that there could not be two competing Kurdish powers.

The DAA faces a number of legal challenges, the most critical of which is their lack of formal recognition by the central government of Syria or any official national agency. The DAA relies solely on its relationship with the US-led international coalition member states for legitimacy. The second legal issue they face is their vague “Social Contract,” that has many ambiguous and overlapping political concepts. The “Social Contract,” in some cases, contradicts the DAA’s traditional ideological and theoretical foundations. On one hand, the DAA claims that it wants to dispose of the authority of a central government, but in reality, it tied all of aspects of social life with its institutions, and established a monopoly on governance through an intricate bureaucracy of the various communes, councils, and a variety of military formations. The revised the “Social Contract” which proclaims the establishment of “The Democratic Federation of Northern Syria,” presents concepts that are unprecedented in Syrian political history, such as the mixing of pagan and monotheistic concepts thought the use phrases like the “the Mother God” and “I Swear by Allah the Most Great” in the same text. The “Social Contract” was ineffective as a constitution for an autonomous or federal region. Instead, it creates a system that acts more like a confederation since the social contract grants political asylum, builds diplomatic relations, and grants the right to self-determination.

Another issue with the “Social Contract,” is rooted in the DAA’s geographic expansion and unilateral establishment of a so-called “federation,” in the absence of willing and capable partners that represent the large populations like the KNC, and of representatives for places that they have recently taken control of in Raqqa city and the northern part of the province, southern rural Hasaka, and Deir Ezzor countryside. These are majority Arab populations that may reject the legitimacy of a majority Kurdish power structure, and existing local administrative bodies will not be easily convinced to accept such an alliance in their local administration. The most obvious of challenges facing the DAA’s project is the fact that Syria is in a state of constant political and military instability, and regional and international powers still disagree on a format or timeline for political transition in Syria.

The PYD has insisted on adoption of the “democratic nation” concept, and promotes it at a regional level as a solution to the Kurdish question and the problems of other groups. Despite some similarities between their project and the confederation system existing in Europe today, it lacks freedom of application or amendment, because the PYD considers it to be complete and only option. This system also lacks the support of any regional political force. Its policies also conflict with the social reality of eastern Syria, where religion governs many aspects of social life. The philosophy of the “democratic nation” is transnational and cross-border in nature, thus distracting attention away from Kurdish national rights within different countries of the region.

The “Democratic Nation” faces a number of obstacles that have emerged on a local level during its implementation, such as the militarization of society through the formation of groups like the Civilian Defense Forces (HPC), an armed civilian volunteer force responsible for neighborhood security. Furthermore, there are disproportionately large military and security forces compared to the areas and population under the DAA’s control.

The DAA also created a centralized bureaucracy that burdens those managing it. Instead of moving away from the former centralized governing system of the regime, they established a new even more centralized system. Its governing domain expanded significantly and disproportional to the size of the territory and the populating living within it. The DAA also contradicted itself by enforcing a uniform “Social Contract” that does not take into consideration the plural norms and belief systems of the local populations.

Given the size of its control and influence on the Syrian map, if the DAA continues in its current form, it will destroy one of the most important pillars of its political theory: the rejection of modern nation states structures and the borders that create divisions between the people. Instead, the DAA today is responsible for cutting ties between people in the city of Raqqa and its southern countryside, Deir Ezzor and its countryside, and parts of the northern Aleppo countryside.

([1]) See Omran Center for Strategic Studies previous report about internal SDF conflicts, “Military and Security Structures of the Autonomous Administration,” https://goo.gl/MX2dmq

([2]) The international coalition announces the killing of two soldiers after being targeted in Manbij, Source: Northern Syria Observer, Date: 30/03/2018, Link: https://goo.gl/Y1SBN4

([3]) The “Popular Resistance” attacks and American military base in Raqqa, Source: Syria News, Date: 02/04/2018, Link: https://goo.gl/7smXXv

([4]) The Kurdish Qandil Mountains, Source: Stratfor orldview., Date: 28/03/2013, Link: https://goo.gl/J2SGz4

([5]) On the second anniversary of its announcement: Opinions about the Autonomous Administration’s works, Source: Buyer Press, Date: 01/21/2016, Link: https://goo.gl/jp1RhC

([6]) The failure of negotiations between TEV-DEM and KNC occurred for many reasons, notably the conflict between the different regional Kurdish factions supporting the two councils.

([7]) Analysis of the Social Contract of the Northern Federation, Source: Omran Center for Strategic Studies, 08/16/2016, Link: https://goo.gl/6fJedS

([8]) Full text of the “Social Contract of the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria” http://vvanwilgenburg.blogspot.com/2017/03/social-contract-of-democratic.html#!/2017/03/social-contract-of-democratic.html

([9]) Program at Kurdish Center: The video shows experts: The Kurds take apart northern Syria, Source: Masr Al Arabiya, Date: 07/20/2016, Link: https://goo.gl/xKCQGM

([10]) In reference to the subject of identity, it is important to note that nation states emerged in the Middle East following the collapse of the empires of past years. The legacy of this experience was that the locals were unable to create a succinct all-encompassing political identity. For example, the Turkish Republic, which has its roots in the legacy of the Ottoman Empire, is unable to overcome the conception of a single ethnicity and accept that the country is made up a multitude of ethnicities. Similarly, the Islamic Republic of Iran is unable to escape the legacy of the Shah, and cannot clearly identify as Persian nor live in peace in a region that is plagued with plentiful ideological differences. Based on this we can observe that the political structures at the bottom of the governance pyramid in the DAA suffer from the lack of a clear identity. The PYD rejects a Kurdish nationalist identity but at the same time calls for holding a “Kurdistan Conference.” The PYD also denies its core relationship with the PKK, while the success of “Rojava” and the Democratic Autonomous Administration are attributed to Abdullah Öcalan personally, the de facto leader of the PKK. The PYD also compromises its own identity when it is politically convenient. For example, the Syrian Democratic Forces are allied with the capitalist United States, putting the PYD in direct contradiction with the Marxist ideology that it still subscribes to.

([11]) Kurdish presence in northern Syria, Akrad Mountains, Afrin, Source: Madarat Kurd, Date: 04/12/2016 https://goo.gl/7upuYf

([12]) The area of Jabal al-Kurd or the Kurds or Old Kordag is in the northernmost corner of the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. It forms the northwest corner of the Fertile Crescent of the State of Syria, and the heights of the end of the southwest of the Taurus Mountains. The mountains of Jabal al-Kurd begin in the upper reaches of the rivers of Afrin and the west of the city of Gaziantep (Kurdish name Delok) within the Turkish border regions, and are a natural extension of the mountains of Reşa and Zagê of the Kurdish areas in the north and east. The peaks take a northerly northward direction with a slight deviation to the west and a length of about 100 km to its southwestern end, west of the town of Gondirasafrin. Its width ranges between 25 and 45 km. Joining this mountainous region, Mount Lilon and Juma Plain, they have historically formed a single, integrated geographical area along the river valley of Afrin.

([13]) Syria’s population 2018, The numbers are estimates due to the lack of viable partners and resources to collect accurate data, Source: World Population Review, Date: 06/04/2018, Link: https://goo.gl/4uX9bc.

([14]) Janet Biehl, Bookchin, Öcalan, and the Dialectics of Democracy, 2012, http://new-compass.net/articles/bookchin-%C3%B6calan-and-dialectics-democracy

([15]) Dana Jalal, Democratic nation is a new human identity, 2011, http://www.ahewar.org/debat/show.art.asp?aid=258651

([16]) He includes in his arguments explanations of the development of the Sumerian priests and the way to democratic civilization as humans. He treat the Sumerians as if they were the first to establish a "state" in history, followed by the Egyptian, Chinese, Buddhist, Confucian, and Greek civilizations, the birth of monotheistic religions, Islam's dismantling of the slave system, reaching the capitalist civilization and world's general state of identity crisis. He concludes that the concept of the “democratic nation” is inclusive of all previous civilizations with their divine and human characteristics, and that it is a nation of multiple identities, cultures, and political entities in the face of the monsters of the nation-state.

([17]) Sihanouk Dibbbo: Towards a democratic solution to the Kurdish issue; a battle between Ra' and Aviv, Source: Fourth Power, Author: Sihanouk Dibo, Date: 08/29/2016, link: https://goo.gl/JXVxAv

([18]) The Democratic Nation, Source: The Center for Kurdish Studies, Author: Yusuf al Khaldi, Date: 06/23/2016, Link: https://goo.gl/tLRtXo

([19]) Local administration in Kurdish Syrian territories: Afrin as a case study, Source: Omran Center for Strategic Studies, Date: 03/07/2015, Link: https://goo.gl/c5MpXp

([20]) The two councils: Legislative and Executive, discuss the yearly budget for 2015 and the expenses of 2014, Source: Buyer Press, Date: 03/17/2015, Link: https://goo.gl/QLvB7e

([21]) The social contract of the democratic autonomous administration in the al-Jazira canton of Syria was approved during session no. 1 on 01/06/2014, Source: Legislative Committee, Link: https://goo.gl/2bgcde

([22]) The Industrial City project in Derik: Between the Municipalities insistence and the factory owners’ rejections!, Source: Qasyoun Agency, Date: 09/16/2017, Link: https://goo.gl/PmYkaD

([23]) PYD aggression unde the guise of taxation from the people’s pockets to the war chests, Source: NSO, Date: 07/20/2017, Link: https://goo.gl/429A2m

([24]) The state of education in the Autonomous Administration, Source: Omran Center for Strategic Studies, Date: 12/15/2016, Link: https://goo.gl/WRn8YP

([25]) The Fifth Arts and Culture Conference in Rojava, Source: Rojava press, Link: https://goo.gl/Kr8U94

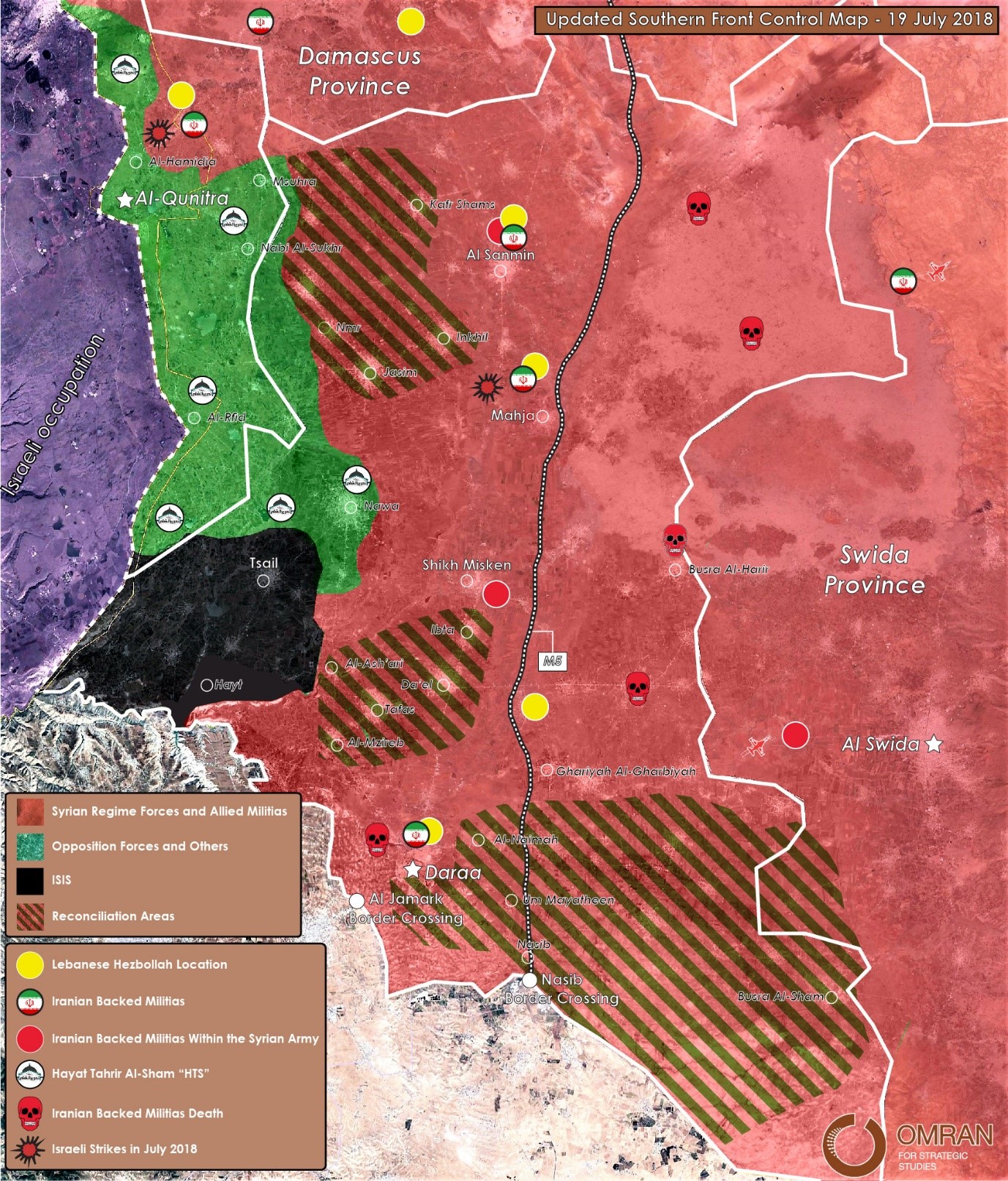

Iranian Involvement in Syria’s Southern Front

This report presents a brief account of latest developments in southern Syria, covering the Daraa and Qunaitera fronts with a specific focus on Iranian involvement from late May until July 17. Prior to the latest escalation along the southern border of Syria, there were reports of an initial agreement between Israel and Russia to push back Iranian and Iranian-backed forces along Syria’s border with Israel. The Iranians reacted by incorporating many of its militias and forces into the Syrian army to continue fighting in the area. Photographs and videos posted on pro-regime media as well as accounts belonging to some of the Iranian-backed militias confirm their involvement. In the final agreement between opposition forces and Russia involving parts of Eastern Daraa and Daraa city, green buses headed to the area to prepare the transportation of a small number of the opposition members to Idlib, while other areas concluded reconciliation agreements. Other areas to the west of Daraa are still going through negotiations to finalize the terms of their agreements. The Russians are pushing for an agreement where minimum number of residents are displaced to Idlib, as a deal to receive them was not concluded with Turkey. At the same time, Iranian forces are pushing for the escalation of attacks to take full control of all southern regions.

Background

In late May 2018, Israel and Russia agreed that Iranian and Iranian-backed forces would vacate areas in southwestern Syria near the Israeli border([1]). Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that due to the Syrian army’s recent advances, foreign forces should withdraw from Syria and mentioned Turkish, American, Iranian and Hezbollah soldiers specifically when asked to clarify. Iranian Foreign Ministry representative Bahram Qassemi responded that Iran would remain in Syria while terrorism exists and for as long as the Syrian government wants Iranian forces there([2]). Nevertheless, in order to reduce pressure from Israel, Iranian-backed forces – including some of Hezbollah members – withdrew from areas in southern Syria only to return as integrated units within the Syrian Army structure. Examples of Iranian-backed forces within the Army include the following:

- 313th Brigade: This brigade is stationed at the Cultural Center in the city of Azra. Brigade fighters withdrew from the city of Daraa in the first week of June and went back to their main base in Sa'Sa.

- Quneitra Hawks: This force is comprised of 200 fighters and was affiliated with Lebanese Hezbollah. It was initially de-mobilized in Khan Arnabeh and then immediately regrouped and joined the 7th Division of the Syrian Army.

- Iranian-backed militias are now stationed in the hills surrounding the towns of Tel Musabah, Tel Arabad, Tel Marz, Tel Ghassem and Tel Ghashim, before they were divided into three units and re-deployed.

- A group of Lebanese Hezbollah fighters were deployed to the town of Khan Arnebeh as part of the 5th Division.

- Al Ghith Forces: This force is affiliated with the 4th Division and was deployed in Khdir Village, on the west side of Majdal Shams.

- Abu al-Fadl al-Abbas Brigade: This brigade withdrew from Eastern Ghouta and moved towards Damascus, only to return after a few days. It is now stationed at Khan Aranbeh and Al-Baath City in Quneitra, at the base of the 10th Brigade in Qantara. Information Unit Sources confirmed the existence of a training camp for the fighters of Abu al-Fadl al-Abbas in Qalmoun, which includes Afghan and Pakistani fighters. The objective of the camp is to send them to the southern front until the Syrian government prepares new identity cards for these fighters as Syrian citizens.

In early June, Russia began deploying troops near territories occupied by Israel, indicating Moscow’s preference for decreased Iranian presence in Syria and despite the dominant presence of Hezbollah in the area. Sources confirmed that Hezbollah was not happy with Russian moves and would demand Russian withdrawal, similar to what happened in Al-Qusir, Homs in the first week of June. Conveying Iranian opinion, Brig. Gen. Masoud Jazayeri told Lebanon’s al-Manar, “Iran and Syria enjoy deep relations that would not be influenced by the propaganda measures of anyone,” adding also that Lebanese militias would not leave Syria([3]).

Attack Stage

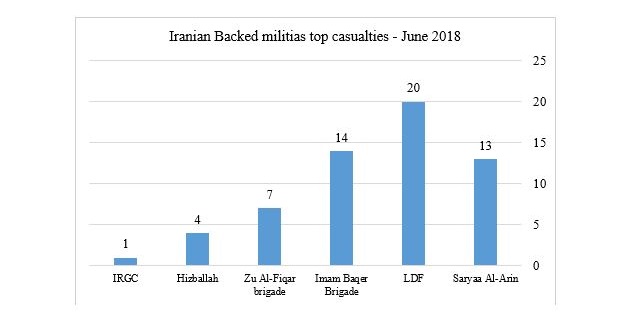

The following is a list of top Iranian-backed militias and forces involved in the escalation of violence in the southern front:

| Militia Name | Origin | Situation in Syria |

| Imam al Baqir Brigade | Syria | Part of LDF |

| Lebanese Hezbollah | Lebanon | Special Forces |

| Saryaa Al-Arin | Syria | Military Security Branch |

| Zu Al-Fiqar Brigade | Iraq | Republican Guard |

| Imam Hussein Brigade | Iraq | Militia |

| Al Quds Brigade | Palestine | Militia |

| Abu Fadl Al-Abba | Iraq | Republican Guard |

| A Taha Regiment | Syria | Tiger Forces |

| Arab National Guard | Mix | Militia |

| Salah Al-Assi groups | Syria | Tiger Forces |

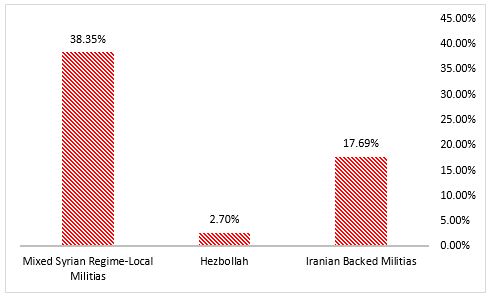

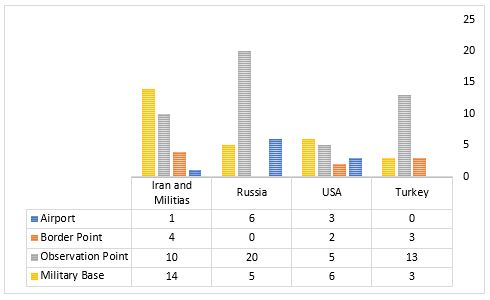

| IRGC | Iran | Military supervision |