Papers

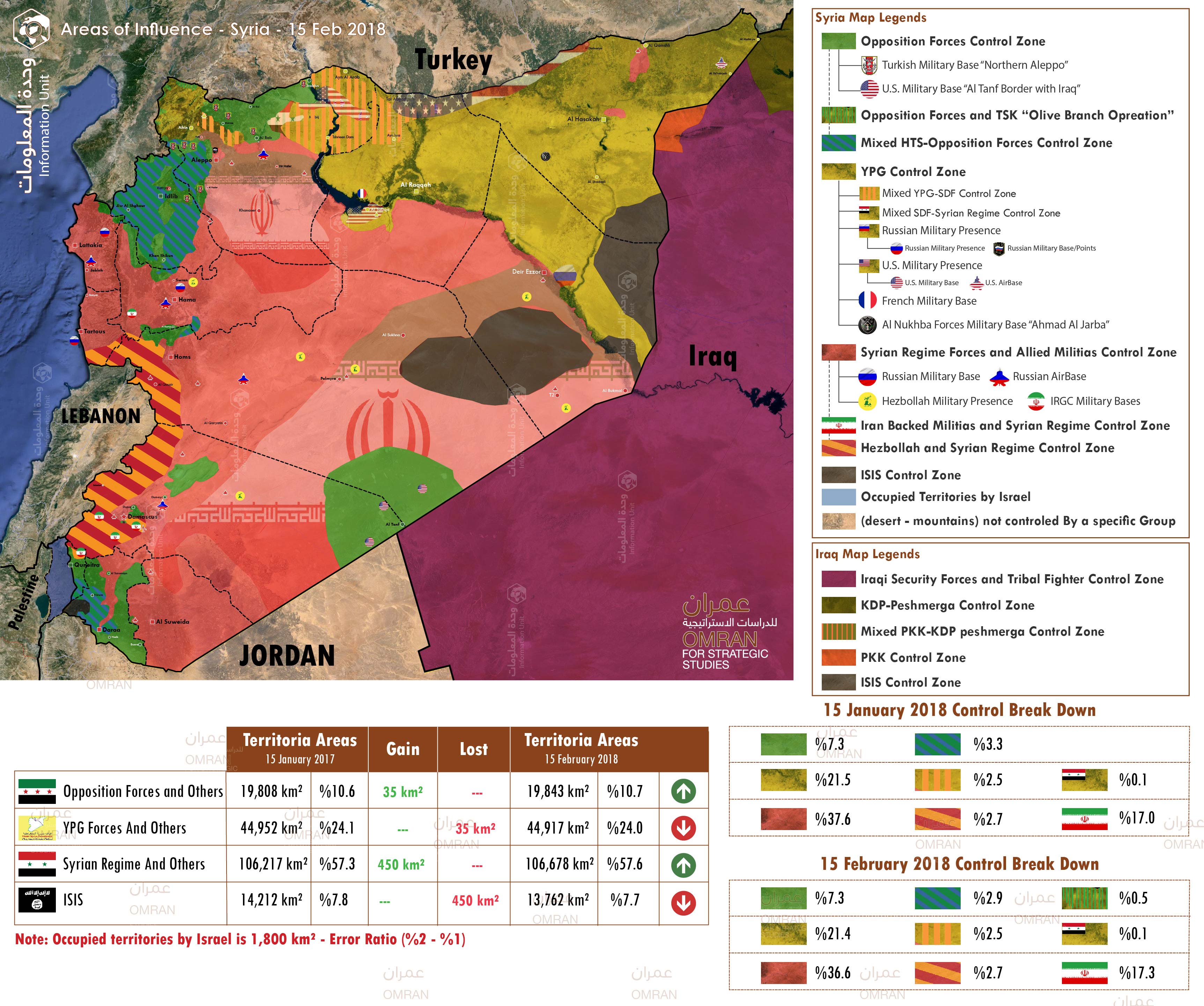

Map of Control and Influence in Syria February 16, 2018

Map of Control and Influence in Syria:

- Turkish Armed Forces (TAF) and the Free Syrian Army (FSA) captured several locations in the western region of Afrin from the YPG/YPJ. Separately, reports emerged claiming that the TAF and the FSA had deployed additional troops and equipment west of the Jandaris district indicating an upcoming offensive.

Pro-YPG sources said that Kurdish forces had repelled Turkish attacks in the districts of Rajo and Bulbul, and claimed that more than 20 Turkish-backed fighters were reportedly killed there.

February 5: A massive Kurdish military convoy entered the Afrin region to support the YPG in its fight against the Turks. As a result, many issues were raised:

- The number of vehicles that left Manbij was 36, but 41 entered Afrin, meaning five extra vehicles joined the convoy from areas controlled by pro-Iran forces.

- After the convoy entered Afrin from a checkpoint in Nubl and Zahraa, areas controlled by pro-Iran forces, multiple Iranian weapons were spotted in the possession of Kurdish forces. Below is a full list of these weapons.

2. Syrian regime and pro-Iran forces, as well as US-backed forces, are reportedly amassing troops and fortifying their positions in the Euphrates region. According to both pro-opposition and pro-government sources, the two sides are preparing for possible skirmishes in the area.

3. February 10: Israeli airstrikes destroyed nearly half of the Syrian regime’s air defenses, according to the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, which cited “senior Israeli Defense Forces officials” in the article on February 14. An Israeli F-16 was shot down during the airstrike; however, Israeli officials considered the operation a success.

February 12: AnIsraeli military official said that an Iranian drone shot down 10 February 2018, ago was based on a US stealth RQ-170 UAV, which was captured by Iran in 2011. Iran started production of this drone in 2016.

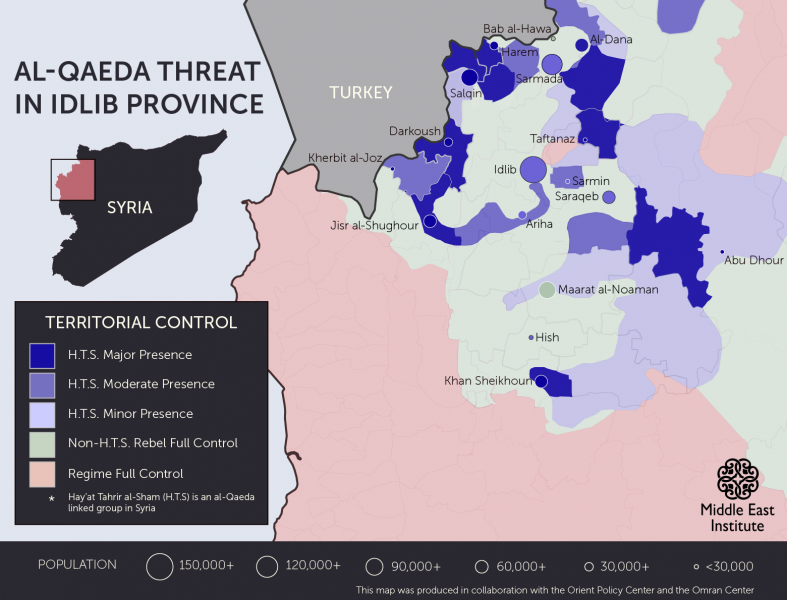

Al-Qaeda Affiliate and Ahrar al-Sham Compete for Control in Idlib

"This special report was published byMiddle East Institute , in collaboration with Omran for Strategic Studies, andOPC- Orient Policy Center"

Idlib is currently the site of increasing competition between the two most dominant armed coalitions, the al-Qaeda-linked Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (H.T.S.) and Ahrar al-Sham. The province has witnessed limited airstrikes since a de-escalation agreement, which came into effect on May 5, was brokered by Russia, Turkey, and Iran at the Astana talks. Idlib was one of four areas labeled as a de-escalation zone.

The agreement has, however, prompted a contest between H.T.S. and Ahrar al-Sham, with both groups vying to increase their influence and control new areas. The competition between them has three dimensions: military, economic, and social.

For strategic, economic, and military reasons, H.T.S. has focused efforts on controlling vital towns, specifically along the Syrian-Turkish border on the western side of the province. H.T.S. fighters that shifted to the region from losses in Aleppo and Homs were deployed carefully in areas where the al-Qaeda affiliate wanted to increase influence, particularly along the northwestern border.

The “smuggling” route along the border from Harem to Darkoush is totally controlled by H.T.S., which uses it to transport oil and other goods. The mountainous nature of the area and its many caves also allow H.T.S. to thwart any attack or attempts by Ahrar or any other group to assert control in those territories.

Though H.T.S. controls military bases in the area, such as Taftanaz, to the northeast of Idlib, and Abu Dhour, southeast of Idlib, the group faces challenges in governance. Lacking communal support and strong governing skills, H.T.S. can’t fully control major cities like Idlib, Maarat al-Noaman, and Saraqib. Even in smaller towns like Kafranbel, where civil society has been active, H.T.S. has also failed to maintain a tight grip.

The experience of Maarat al-Noaman is an example of how local communities have played a major role in confronting H.T.S. Since February 2016, civil society has actively mobilized against al-Qaeda’s presence, first against Jabhat al-Nusra, as they were called at the time, and later against present-day H.T.S. The group was unable to control the city or defeat armed opposition groups largely due to the local community’s support for the armed groups. “It is not the armed groups there that protected civil society and the local community, it’s the community that prevented H.T.S. from defeating the armed opposition inside the city,” said Basel al-Junaidy, director of Orient Policy Center.

The only large city H.T.S. has been able to control is Jisr al-Shughour, in part because the armed groups surrounding the city are loyal to Abu Jaber, the former leader of Ahrar al-Sham who defected to H.T.S. earlier this year.

Following increasing pressure from Turkey to protect its borders, H.T.S. delegated to Ahrar al-Sham control over parts of the northwestern border near the town of Salqin. However, H.T.S. still enjoys influence there, and Ahrar still needs H.T.S. approval to appoint the leader of the group assigned to watch the border in that area.

Yet the current map could also be misleading. There are areas where H.T.S. has presence, but struggles to maintain control, and there are areas where it does not yet have a presence, but could expand power if threatened. For example, the main border crossing between Idlib and Turkey is Bab al-Hawa. It is controlled by Ahrar al-Sham, but H.T.S. controls the route leading to the crossing through several checkpoints, and has the capability to attack the border crossing and seize control at will.

In the north, Sarmada is becoming the economic capital of Idlib. H.T.S. controls most of the decision-making there with regards to regulations like money transfers, the exchange rate, and the prices of commodities like metal and oil. On the other hand, H.T.S. is weakest in southern Idlib, from the borders of the Hama province to Ariha, the social base for Ahrar al-Sham.

H.T.S. governs through its General Directorate of Services, which competes with several other entities to provide services. These competitors include Ahrar al-Sham’s Commission of Services, local councils under the umbrella of the opposition interim government, independent local councils, and civil society organizations. A recent study conducted by the Omran Center shows that there are 156 local councils in the province of Idlib; 81 of them are in areas where H.T.S. has a strong presence. As highlighted above, however, H.T.S. doesn’t enjoy equal control over all of these councils. While in some instances the group has comprised whole councils—as in Harem, Darkoush, and Salqin—in other councils, H.T.S. is only able to influence some members.

Due to the de-escalation zones agreement, H.T.S. currently finds itself in a challenging position. When the Nusra Front established its presence in Syria, it promoted itself as the protector of the people. Escalating violence helped the group gain legitimacy and sympathy, and many armed groups found a strong ally in the al-Qaeda affiliate as battles raged against the regime. As front lines become quieter, H.T.S. is beginning to lose its appeal.

The H.T.S. alliance also faces internal threats. The dynamics are changing between Nusra and the Nour al-Din al-Zenki movement, the second largest component of H.T.S. On June 2, Hussam al-Atrash, a senior leader of Zenki, tweeted that areas out regime control should be handed over to the opposition interim government, and all armed groups should dissolve. Atrash justified his suggestion as the only way for the Sunni armed opposition forces to survive. The comments irritated H.T.S. leadership, which referred Atrash to the H.T.S. judiciary. The tweets disappeared shortly thereafter.

Following that incident, H.T.S. banned all fighters from mentioning any subgroup names, like Zenki, to enforce unity. However, it is unlikely that H.T.S. will be able to maintain long-term enforcement. No opposition military alliance has been able to survive throughout the Syrian conflict, and subgroups continue to migrate from one umbrella to another for tactical reasons, seeking military protection and/or new funding opportunities.

While H.T.S. faces these internal and external challenges, it is also evolving. Its leadership clearly realized the importance of building stronger connections with local communities in order to compete with Ahrar al-Sham. H.T.S. adopted new tactics in governing. Instead of appointing foreigners or military leaders, H.T.S. has appointed local civilians as its representatives in most of the towns under its control in Idlib.

H.T.S. and Ahrar will continue to compete in governance and service provision, which is key to building loyalty, increasing influence, and widening public support. The groups are also cautiously following regional and international developments as they prepare for different scenarios. If the de-escalation agreement collapses or an external force intervenes in Idlib, all dynamics will certainly change. Ahrar and H.T.S. might confront each other, become allies, or re-shuffle their respective coalitions. The situation in Idlib is far from stable.

Geopolitical Realignments around Syria: Threats and Opportunities

Abstract: The Syrian uprising took the regional powers by surprise and was able to disrupt the regional balance of power to such an extent that the Syrian file has become a more internationalized matter than a regional one. Syria has become a fluid scene with multiple spheres of influence by countries, extremist groups, and non-state actors. The long-term goal of re-establishing peace and stability can be achieved by taking strategic steps in empowering local administration councils to gain legitimacy and provide public services including security.

Introduction

Regional and international alliances in the Middle East have shifted significantly because of the popular uprisings during the past five years. Moreover, the Syrian case is unique and complex whereby international relations theories fall short of explaining or predicting a trajectory or how relevant actors’ attitudes will shift towards the political or military tracks. Syria is at the center of a very fluid and changing multipolar international system that the region has not witnessed since the formation of colonial states over a century ago.

In addition to the resurrection of transnational movements and the increasing security threat to the sovereignty of neighboring states, new dynamics on the internal front have emerged out of the conflict. This commentary will assess opportunities and threats of the evolving alignments and provide an overview of these new dynamics with its impact on the regional balance of power.

The Construction of a Narrative

Since March 2011, the Syrian uprising has evolved through multiple phases. The first was the non-violent protests phase demanding political reforms that was responded to with brutal use of force by government security and military forces. This phase lasted for less than one year as many soldiers defected and many civilians took arms to defend their families and villages. The second phase witnessed further militarization of civilians who decided to carry arms and fight back against the aggression of regime forces towards civilian populations. During these two phases, regional countries underestimated the security risks of a spillover of violence across borders and its impact on the regional balance of power. Diplomatic action focused on containing the crisis and pressuring the regime to comply with the demands of the protestors, freeing of prisoners, and amending the constitution and several security based laws.

On the other hand, the Assad regime attempted to frame a narrative about the uprising as an “Islamist” attempt to spread terrorism, chaos and destruction to the region. Early statements and actions by the regime further emphasized a constructed notion of the uprising as a plot against stability. The regime took several steps to create the necessary dynamics for transnational radical groups (both religious and ethnic based) to expand and gain power. Domestically, it isolated certain parts of Syria, especially the countryside, away from its core interest of control and created pockets overwhelmed by administrative and security chaos within the geography of Syria where there is a “controlled anarchy”. It also amended the constitution in 2012 with minor changes, granted the Kurds citizenship rights, abolished the State Security Court system but established a special terrorism court that was used for protesters and activists. The framing of all anti-regime forces into one category as terrorists was one of the early strategies used by the regime that went unnoticed by regional and international actors. At the same time, in 2011 the regime pardoned extremist prisoners and released over 1200 Kurdish prisoners most of whom were PKK figures and leaders. Many of those released later took part in the formation of Jabhat al-Nusra, ISIS, and YPG forces respectively. This provided a vacuum of power in many regions, encouraging extremist groups to occupy these areas thus laying the legal grounds for excessive use of force in the fight against terrorism.

The third phase witnessed a higher degree of military confrontations and a quick “collapse” of the regime’s control of over 60% of Syrian territory in favor of revolutionary and opposition forces. Residents in 14 provinces established over 900 Local Administration Councils between 2012 and2013. These Councils received their mandate and legitimacy by the consensus or election of local residents and were tasked with local governance and the administration of public services. First, the Syrian National Council, then later the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces were established as the official representative of the Syrian people according to the Friends of Syria group. The regime resorted to heavy shelling, barrel bombing and even chemical weapons to keep areas outside of its control in a state of chaos and instability. This in return escalated the level of support for revolutionary forces to defend themselves and maintain the balance of power but not to expand further or end the regime totally.

During this phase, the internal fronts witnessed many victories against regime forces that was not equally reflected on the political progress of the Syria file internationally. International investment and interference in the Syrian uprising increased significantly on the political, military and humanitarian levels. It was evident that the breakdown of the Syrian regime during this phase would threaten the status quo of the international balance of power scheme that has been contained through a complex set of relations. International diplomacy used soft power as well as proxy actors to counter potential threats posed by the shifting of power in Syria. Extremist forces such as Jabhat al-Nusra, YPG and ISIS had not yet gained momentum or consolidated territories during this phase. The strategy used during this phase by international actors was to contain the instability and security risk within the borders and prevent a regional conflict spill over, as well as prevent the victory of any internal actor. This strategy is evident in the UN Security Council Resolution 2042 in April 2012, followed by UNSCR 2043, which call for sending in international observers, and ending with the Geneva Communique of June 2012. The Geneva Communique had the least support from regional and international actors and Syrian actors were not invited to that meeting. It can be said that the heightened level of competition between regional and international actors during this phase negatively affected the overall scene and created a vacuum of authority that was further exploited by ISIS and YPG forces to establish their dream states respectively and threaten regional countries’ security.

The fourth phase began after the chemical attack by the regime in August of 2013 where 1,429 victims died in Eastern Damascus. This phase can be characterized as a retreat by revolutionary military forces and an expansion and rise of transnational extremist groups. The event of the chemical attack was a very pivotal moment politically because it sent a strong message from the international actors to the regional actors as well as Syrian actors that the previous victories by revolutionary forces could not be tolerated as they threatened the balance of power. Diplomatic talks resulted in the Russian-US agreement whereby the regime signed the international agreement and handed over its chemical weapons through an internationally administered process. This event was pivotal as it signified a shift on the part of the US away from its “Red Line” in favor of the Russian-Iranian alignment, which perhaps was their first public assertion of hegemony over Syria. The Russian move prevented the regime’s collapse and removed the possibility of any direct military intervention by the United States. It is at this point that regional actors such as Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia began to strongly promote a no-fly zone or a ‘safe zone’ for Syrians in the North of Syria. During this time, international actors pushed for the first round of the Geneva talks in January 2014, thus giving the Assad regime the chance to regain its international legitimacy. Iran increased its military support to all of Hezbollah and over 13 sectarian militias that entered Syria with the objective of regaining strategic locations from the opposition.

The lack of action by the international community towards the unprecedented atrocities committed by the Syrian regime, along with the administrative and military instability in liberated areas created the atmosphere for cross-border terrorist groups to increase their mobilization levels and enter the scene as influential actors. ISIS began gaining momentum and took control over Raqqa and Deir Azzour, parts of Hasaka, and Iraq. On September 10, 2014, President Obama announced the formation of a broad international coalition to fight ISIS. Russia waited on the US-led coalition for one year before announcing its alliance to fight terrorism known as 4+1 (Russia, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Hezbollah) in September 2015. The Russian announcement came at the same time as ground troops and systematic air operations were being conducted by the Russian armed forces in Syria. In December 2015, Saudi Arabia announced the formation of an “Islamic Coalition” of 34 largely Muslim nations to fight terrorism, though not limited to ISIS.

These international coalitions to fight terrorism further emphasized the narrative of the Syrian uprising which was limited to countering terrorism regardless of the internal outlook of the agency yet again confirming the regime’s original claims. As a result, the Syrian regime became the de facto partner in the war against terrorism by its allies while supporters of the uprising showed a weak response. The international involvement at this stage focused on how to control the spread of ISIS and protect each actor from the spillover effects. The threat of terrorism coupled with the massive refugee influx into Europe and other parts of the world increased the threat levels in those states, especially after the attacks in the US, France, Turkey and others. Furthermore, the PYD-YPG present a unique case in which they receive military support from the United States and its regional allies, as well as coordinate and receive support from Russia and the regime, while at the same time posing a serious risk to Turkey’s national security. Another conflictual alliance is that of Baghdad; it is an ally of Iran, Russia and the Syrian regime; but it also coordinates with the United States army and intelligence agencies.

The allies of the Assad regime further consolidated their support of the regime and framing the conflict as one against terrorism, used the refugee issue as a tool to pressure neighboring countries who supported the uprising. On the other hand, the United States showed a lack of interest in the region while placing a veto on supporting revolutionary forces with what was needed to win the war or even defend themselves. The regional powers had a small margin between the two camps of providing support and increasing the leverage they have on the situation inside Syria in order to prevent themselves from being a target of such terrorism threats of the pro-Iran militias as well as ISIS.

In Summary, the international community has systematically failed to address the root causes of the conflict but instead concentrated its efforts on the conflict's aftermath. By doing so, not only has it failed to bring an end to the ongoing conflict in Syria, it has also succeeded in creating a propitious environment for the creation of multiple social and political clashes, hence aggravating the situation furthermore. The different approaches adopted by both the global and regional powers have miserably failed in re-establishing balance and order in the region. By insisting on assuming a conflictual stance rather than cooperating in assisting the vast majority of the Syrian people in the creation of a new balanced regional order, they have assisted the marginalized powers in creating a perpetual conflict zone for years to come.

Security Priorities

The security priorities of regional and international actors have been in a realignment process, and the aspirations of regional hegemony between Turkey, Arab Gulf states, Iran, Russia and the United States are at odds. This could be further detailed as follows:

• The United States: Washington’s actions are essentially a set of convictions and reactions that do not live up to its foreign policy frameworks. The “fighting terrorism” paradigm has further rooted the “results rather than causes” approach, by sidelining proactive initiatives and instead focusing on fighting ISIS with a tactical strategy rather than a comprehensive security strategy in the region.

• Russia: By prioritizing the fight against terror in the Levant, Moscow gained considerable leverage to elevate the Russian influence in the Arab region and an access to the Mediterranean after a series of strategic losses in the Arab region and Ukraine. Russia is also suffering from an exacerbating economic crisis. Through its Syria intervention, Russia achieved three key objectives:

1. Limit the aspirations and choices of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey in the new regional order.

2. Force the Iranians to redraft their policies based on mutual cooperation after its long control of the economic, military and political management of the Assad regime.

3. Encourage Assad’s allies to rally behind Russia to draft a regional plan under Moscow’s leadership and sphere of influence.

• Iran: Regionally, Iran intersects with Washington and Moscow’s prioritizing of fighting terrorism over dealing with other chronic political crises in the region. It is investing in fighting terrorism as a key approach to interference in the Levant. The nuclear deal with Iran emerged as an opportunity to assign Tehran as the “regional police”, serving its purpose of exclusively fighting ISIS. The direct Russian intervention in Syria resulted in Iran backing off from day-to-day management of the Syrian regime’s affairs. However, it still maintains a strong presence in most of the regional issues – allowing it to further its meddling in regional security.

• Turkey: Ankara is facing tough choices after the Russian intervention, especially with the absence of US political backing to any solid Turkish action in the Levant. It has to work towards a relative balance through small margins for action, until a game changer takes effect. Until then, Turkey’s options are limited to pursuing political and military support of the opposition, avoiding direct confrontation with Russia and increasing coordination with Saudi Arabia to create international alternatives to the Russian-Iranian endeavors in the Levant. Turkey’s options are further constrained by the rise of YPG/PKK forces as a real security risk that requires full attention.

• Saudi Arabia: The direct Russian intervention jeopardizes the GCC countries’ security while it enhances the Iranian influence in the region, giving it a free hand to meddle in the security of its Arab neighbors. With a lack of interest from Washington and the priority of fighting terror in the Levant, the GCC countries are only left with showing further aggression in the face of these security threats either alone or with various regional partnerships, despite US wishes. One example is the case in Yemen, where they supported the legitimate government. Most recently in Lebanon, it cut its financial aid and designated Hezbollah as a terrorist organization. Riyadh is still facing challenges of maintaining Gulf and Arab unity and preventing the plight of a long and exhausting war.

• Egypt: Sisi is expanding Egyptian outreach beyond the Gulf region, by coordinating with Russia which shares Cairo’s vision against popular uprisings in the Arab region. He also tries to revive the lost Egyptian influence in Africa, seeking economic opportunities needed by the deteriorating Egyptian economic infrastructure.

• Jordan: It aligns its priorities with the US and Russia in fighting terrorism, despite the priorities of its regional allies. Jordan suffices with maintaining security to its southern border and maintaining its interests through participating in the so-called “Military Operation Center - MOC”. It also participates and coordinates with the US-led coalition against terrorism.

• Israel: The Israeli strategy towards Syria is crucial to its security policy with indirect interventions to improve the scenarios that are most convenient for Israel. Israel exploits the fluidity and fragility of the Syrian scene to weaken Iran and Hezbollah and exhaust all regional and local actors in Syria. It works towards a sectarian or ethnic political environment that will produce a future system that is incapable of functioning and posing a threat to any of its neighbors.

During the recent Organization of Islamic Cooperation conference in Istanbul the Turkish leadership criticized Iran in a significant move away from the previous admiration of that country but did not go so far as cutting off ties. One has to recognize that political realignments are fluid and fast changing in the same manner that the “black box” of Syria has contradictions and fragile elements within it. The new Middle East signifies a transitional period that will witness new alignments formulated on the terrorism and refugee paradigms mentioned above. Turkey needs Iran’s help in preventing the formation of a Kurdish state in Syria, while Iran needs Turkey for access to trade routes to Europe. The rapprochement between Turkey and the United Arab Emirates as well as other Gulf States signifies a move by Turkey to diffuse and isolate polarization resulting from differences on Egypt and Libya and building a common ground to counter the security threats.

Opportunities and Policy Alternatives

The political track outlined in UNSC 2254 has been in place and moving on a timeline set by the agreements of the ISSG group. The political negotiations aim to resolve the conflict from very limited angles that focus on counter terrorism, a permanent cease-fire, and the maintenance of the status quo in terms of power sharing among the different groups. This political track does not resolve the deeper problems that have caused instability and the regional security threat spillover. This track does not fulfill the security objectives sought by Syrian actors as well as regional countries.

Given the evolving set of regional alignments that has struck the region, it is important to assess alternative and parallel policies to remain an active and effective actor. It is essential to look at domestic stabilizing mechanisms and spheres of influence within Syria that minimize the security and terrorism risks and restore state functions in regions outside of government control. Local Administration Councils (LAC) are bodies that base their legitimacy on the processes of election and consensus building in most regions in Syria. This legitimacy requires further action by countries to increase their balance of power in the face of the threat of terrorism and outflow of refugees.

A major priority now for regional power is to re-establish order and stability on the local level in terms of developing a new legitimacy based on the consensus of the people and on its ability to provide basic services to the local population. The current political track outlined by the UNSC 2254 and the US/Russian fragile agreements can at best freeze the conflict and consolidate spheres of influence that could lead to Syria’s partition as a reality on the ground. The best scenario for regional actors at this point in addition to supporting the political track would be to support and empower local transitional mechanisms that can re-establish peace and stability locally. This can be achieved by supporting and empowering both local administration councils and civil society organizations that have a more flexible work environment to become a soft power for establishing civil peace. Any meaningful stabilization project should begin with the transitioning out of the Assad regime with a clear agreed timetable.

Over 950 Local Councils in Syria were established during 2012-2013, and the overwhelming majority were the result of local electing of governing bodies or the consensus of the majority of residents. According to a field study conducted by Local Administration Councils Unit and Omran Center for Strategic Studies, at least 405 local councils operate in areas under the control of the opposition including 54 city-size councils with a high performance index. These Councils perform many state functions on the local level such as maintaining public infrastructure, local police, civil defense, health and education facilities, and coordinating among local actors including armed groups. On the other hand, Local Councils are faced with many financial and administrative burdens and shortcomings, but have progressed and learned extensively from their mistakes. The coordination levels among local councils have increased lately and the experience of many has matured and played important political roles on the local level.

Regional powers need domestic partners in Syria that operate within the framework of a state institution not as a political organization or an armed group. Local Councils perform essential functions of a state and should be empowered to do that financially but more importantly politically by recognizing their legitimacy and ability to govern and fill the power vacuum. The need to re-establish order and peace through Local Councils is a top priority that will allow any negotiation process the domestic elements of success while achieving strategic security objectives for neighboring countries.

Published In The Insight Turkey, Spring 2016, Vol. 18, No. 2