The Security Situation in Syria and Ways to Manage It

Executive Summary

This paper evaluates and scrutinizes the various security apparatuses in Syria, starting with areas under the political control of the regime, then delving into those held by the opposition, and finally looking into the administratively autonomous regions. Elucidating the measures that must be taken to bring the security services under control, the paper presents a preliminary proposal that describes the security sector, it function, and relationship with the center and the periphery. The proposal seeks to strengthen the conditions of local empowerment while also protecting the stability and unity of the country.

First: The Security Situation in Areas Under the Political Control of the Regime

From the time that allied foreign militias began pouring into Syria and local military groups overseen by senior regime officials began to coalesce, the security apparatuses in regime-held areas could no longer be viewed as cohesive and subject to a regulated and centralized security force. The accumulation of the state security apparatuses’ failures and their inability to face the growing uprising helped to push the regime to take a series of measures that eroded its central hold over the security services. This process began with the formation of auxiliary local militias backed by either the Syrian army or state security services. These policies replaced the regime – and its concentrated authority within the military and security establishments – with mercenaries from among the local population belonging to armed militias that have grown and expanded in both size and influence over the past three years.

These groups represent a real danger to the regime if they slip from its control. For instance, if they develop a large base of followers on the ground and establish strong ties with the local community, this could enable them to both negotiate with the regime for control and influence and work with international groups to further their own special interests, which may conflict with those of the regime. Thus, in 2016, the regime made containing these groups a top priority by restricting the institutionalization of these groups and ensuring their loyalty as a way to safeguarding its own survival and achieving both balance and stability. In general, these measures have had the following consequences:

-

Granting local militias with the power to police the local population and carry out military missions among them.

-

Permitting militias’ security and military functions to grow beyond their localities, allowing most to become centralized militias with departments and branches.

-

Militarizing the community and linking its fate to the regime’s survival and continuity. This has increased the scale of the abuses and violations committed in the name of the state and its citizenry.

-

Institutionalizing these militias by virtue of economic necessity and transforming them into entities that encompass both military strategy and centralized security.

-

Creating military wings for political parties loyal to the Ba’ath Party and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP). This has strengthened these parties’ local authority and rendered them partner security forces linked to the state’s centralized security force through shared benefits and interests.

We Find that the Main Security Apparatuses in Regime-Held Areas are the Following:([1]

1. National Defense Forces (NDF)

Formed in summer 2012 and considered to be by far the largest militia to back the regime, the NDF now encompasses over 100,000 volunteers and is comprised of units spread throughout the country that are overseen by the Syrian army and led by General Hawash Mohammed. The NDF started by organizing and training hundreds of volunteers in People’s Committees. These NDF-trained militias resembled the volunteer Basij militia in the Iranian Revolutionary Guard (IRG), which has given rise to the belief that they were created under the guidance of the leader of the Quds Force in the IRG, Qasem Soleimani.

2. Suqur al-Sahara

Established as an “elite force” by Mohammad Jaber – a businessman closely tied to the regime – the Suqur al-Sahara operates in desert areas and is known to have both participated in the al-Qaryatayn offensive and help recover Kessab village on the Syrian coast. The militia is made up of Alawite and Shiite operatives (as well as individuals from the al-Shaitat clan) and is largely dedicated to fighting ISIS. Comprised of trained operatives – including both current and retired army officers as well as young Syrian volunteers – Suqur al-Sahara is the foremost militia specializing in ambushes and carrying out challenging special operations. Moreover, the militia specializes in protecting oil and gas wells as well as the largest weapons stockpile in the country: theMahin Arms Depot.

3. Al-Bustan Militias

These militias are commanded by the director of the Bustan Charitable Association, which established a security branch that attracts Alawites from Syria’s coast. Functionally and administratively, these militias fall under the purview of the local army divisions in their areas of operation and coordinate their operations with the 18th Division. The most prominent of these militias is Kata’ib al-Jabalawi. Operating in both Homs and Ghouta, it is the most independent of the National Defense militias. Another of these militias is the Leopards of Homs, which was in operation between 2013 and 2015 founded by Shadi Jum’a – a confidant of officer Abu Ja’afar (also known as the Scorpion), who founded the Khyber Brigade, one of the NDF’s militias in Homs. The Leopards of Homs preside over the National Shield forces, which coordinate with the Shiite Zulfiqar militias in Damascus.

4. Coastal Shield Brigade Militia

A statement from the Syrian Republican Guard (SRG) in May 2015 announced the formation of the Coastal Shield Brigade. Comprised of recruits paid a salary of up to 40,000 Syrian Lira, this brigade protects the regime’s main stronghold and maintains its readiness to take in new volunteers to serve in the brigade’s ranks for either two years or an indefinite period of time. Rami Makhlouf and the SRG’s Major General Hassan Mustafa have been tasked with leading the militia with the goal of protecting Alawite villages in the coastal areas. The brigade is made up of defectors from mandatory military enlistment and army reserve service, as well as a number of criminals, who are spread out among the villages of Sanobar – outside of Jableh – and Asitamo.

5. Al-Jazeera and Euphrates Assembly

This is a militia that was formed in the Veterans Hall in Damascus. Sources indicate that this assembly comprises citizens of Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa, and Hasakah and is headed by Riyadh Arsan, who is from Deir ez-Zor but resides in Damascus.

6. Political Militias

These militias arose from political parties and have sought to mobilize their volunteers using partisan and political slogans. The most prominent of these militias are:

-

Ba’ath Brigades: This group was formed by Ba’ath Party members in Aleppo by Commander Hilal Hilal in summer 2012 after rebels managed to enter Eastern Aleppo. These brigades later sprang up in Latakia, Tartus, and even have operations in Damascus.

-

The Eagles of the Whirlwind: This group symbolizes the slogan of the Lebanese SSNP, which, in contrast to the national Ba’ath Party, subscribes to the “Greater Syria” ideology. Approximately 8,000 operatives from the Eagles of the Whirlwind, both Syrian and Lebanese alike, take part in operations in Syria. While their main focus is on Homs and Damascus, they maintain a larger presence in the Suwayda Province than the Syrian army.

-

The Arab National Guard: Formed in 2013 as a national militia made up of nearly 1,000 operatives, the Arab National Guard is stationed in Aleppo, Damascus, Daraa, Homs, and al-Quneitra and made up of nationals from several Arab countries, including Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, Tunisia, Syria, and Yemen. The militia is staffed by several generals as well, including: Wadih Haddad (a Palestinian Christian), Haider al-Amaali (a Lebanese intellectual), Mohammad Borhami (a Tunisian politician), and Julius Jamal.

-

The Syrian Resistance: Formerly named the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Sanjak of Iskandarun, this militia is loyal to the regime and follows a Marxist-Leninist ideology. The militia is led by the Alawite Turk Mihraç Ural (formerly known as Ali Kayyali), who possesses Syrian citizenship and is known for carrying out the Bayda and Baniyas massacres.

7. Sectarian Militias (Christian and Druze)

The most notable include:

- Jaysh al-Muwahhideen: This Druze militia declared its establishment at the start of 2013 and operates specifically in Suwayda, Daraa, Damascus, and other Druze areas. Initially founded to protect the Druze community, the militia now, under the leadership of Ismail Ibrahim al-Tamimi, more broadly supports the Bashar al-Assad regime.

-

Sootoro Forces: Comprised of Syriac Christians and a few Armenians, this is a local militia located in Qamishli in Hasakah Province.

-

The Christian Quwat al-Ghadab: Established in March 2013 in al-Suqaylabiyah Province in the Homs countryside to protect the city and its outskirts, this militia is closely affiliated with the SRG.

-

Valley Lions Brigade: This brigade is led by Beshr al-Yaziji and centrally located in the Krak Des Chevaliers and Wadi al-Nasara areas and their outskirts where they recruit local youth supportive of the regime, often enlisting them to spy on their peers in the opposition. This group purports to protect Christians, who populate over 33 villages in the area. Al-Yaziji maintains a number of security relations, the most important being with Major General Jamil Hassan, and also coordinates with both Brigadier General Haythem Dayoub from the Military Intelligence Directorate (MID) and Colonel Mufeed Warda leader of the Mazhar Haider militia, which is directly linked to the state security services. Every fighter in the brigade is a volunteer that receives his or her salary from the state and is treated like a normal soldier or officer in the armed forces. The brigade uses the SSNP’s Marmarita bureau as a headquarters for coordinating its operations, a meeting place, and a center for both processing volunteer requests and enlisting new volunteers under the supervision of party members. In addition, a large number of the brigade’s members participate in combat operations, some of whom have died in battle, including: Fadi al-Shami and Tony Othman from al-Hawash, Firas Massouh from Marmarita, and Ghassoub Awad from al-Tal.

8. Palestinian Militias

These pro-regime militias were formed by Palestinian refugees both prior to and after the outbreak of the uprising. The Palestinian militias and factions that formed within refugee camps and have been active since the beginning of the uprising include:

-

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) – General Leadership: The role of the PFLP under the leadership of Ahmed Jibril stood out for its suppression of demonstrations in Yarmouk Camp at the beginning of the uprising. The PFLP also supported the Syrian army in its assault on Syrian protestors.

-

Fatah al-Intifada: Established in 1983, this militia is led by Colonel Said al-Muragha.

-

As-Sa’iqa: This group represents the Ba’athist wing of the armed Palestinian factions. It is tied to the Syrian Ba’ath Party and is a member of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).

In addition to these factions, the Palestinian Popular Struggle Front and the Palestinian Democratic Union (including the Return and Liberation Brigades) are also active. Likewise, the regime has assembled Palestinian militias within Syria. Some of these include:

-

Galilee Forces: Comprising nearly 4,800 Palestinian operatives, the Galilee Forces are led by Fadi al-Mallah and trained by the Syrian army and Hezbollah. Having fought in the Battle of Qalamoun, members describe themselves as Syrians by affiliation, Palestinians by nationality, and resistance fighters by faith.

-

Liwa al-Quds: Established in October 2013 and led by Muhammad al-Sa’eed (also known as “The Engineer”), Liwa al-Quds is linked to the Air Force Intelligence Directorate (AFID) and is made up predominantly of Palestinians from Aleppo refugee camps, particularly Al-Nayrab Camp. Their last battle was for control over Handarat Camp in Aleppo.

-

Palestine Liberation Army (PLA): The PLA is led by Tareq al-Khadraa and differs from the Palestine Liberation Army that is subordinate to the PLO in that it has participated in a number of battles within Syria. The group’s most prominent battle took place in Adra, while its most recent was in northern Suwayda, during which it lost 13 fighters. The PLA has also fought battles in Darayya and Tell Souane and has participated in the sieges of Muadamiyat al-Sham and al-Zabadani. With regards to structure, the PLA comprises three brigades: “Hattin Forces” headquartered in the city of Qatana in Rif Dimashq, “Ajnadayn Force” headquartered in Mount Hermon, and “al-Qadissiyah Forces,” which are deployed near the city of Suwayda in southern Syria. Theoretically subordinate to the PLO leadership, in practice the PLA serves the Syrian government. Consequently, when a number of officers and personnel refused early on to enter into the Syrian conflict, they were executed in the field.

9. Druze Militias (in special cases they are absorbed within local authorities)

Suwayda Governorate’s neutrality has helped strengthen local militias, which have begun to take control of civilian life in the area. Checkpoints within the governorate are not all subordinate to the government, as some are administered by NDF militias, set up by People’s Committees, or run by an assortment of operatives from the Humat ad-Diyar militia, the SSNP, and the Ba’ath Brigades. According to local observers, these mixed checkpoints are divided up into gateways used to smuggle fuel into ISIS-controlled areas on the northeastern and south-southwestern borders of the governorate. These checkpoints are important sources of looting, collecting royalties from smuggling operations, and trading black market fuel, flour, and cigarette. Also active within the governorate is a militia with a religious veneer controlled by Nazih Jarbou that, along with other armed militias linked to the regime, is tasked with protecting the local community. Those belonging to this militia fall into three main groups: traders, fuel station owners, and those who need their interests protected.

Second: The Security Structure in Opposition-Held Areas

The decentralization of security bodies in areas held by opposition factions has developed as an alternative model to that of the strict authoritarian system that was in its place when the regime held control. Whereas a number of these security bodies have disappeared, others remain active and continue to provide security services. The first authorities that sought to take on security threats were the local councils, as their leaders were forced to deal early on with a number of issues that arose from the country’s new reality, including those related to security. Among these councils’ tasks was the maintenance of public order and the protection of public property.

The local councils’ role in maintaining security eventually faded for three main reasons:

-

Regime military incursions into areas that had fallen out of its control, which led to a collapse of the initial structure of local governance.

-

The increased militarization of the rebel movement and different factions’ assumption of security and military administration.

-

The emergence of experimental policing units formed by defectors from the security establishment.

Generally, local councils’ preference to leave security duties to competent authorities was driven by the following reasons:

-

The need to reorganize their priorities and refocus on services, particularly with the deterioration of the humanitarian situation and service provisions.

-

An unwillingness to cause friction with opposition military factions.

-

The lack of resources necessary to form security bureaus.

Following is a review of the most important security actors in the opposition controlled areas:([2])

First: Rebel Police

The police forces have experienced a marked increase in defections in comparison to the military and security apparatuses, as an estimated 500 officers and thousands of other personnel have defected. Whereas a portion of defectors withdrew from security detail, a number of them have joined opposition security apparatuses in rebel-held areas. These rebel factions have worked in cooperation with civilians, particularly with the increase in popular discontent caused by the rise in theft, crime, and encroachment on public property. By the end of 2011 and start of 2012, the following policing experiments had begun to manifest throughout the country: The Judicial Police in Huraytan and Tell Rifaat, the Revolutionary Security Bureau, and the Revolutionary Outposts in most regions outside of regime control.

This policing experiment became more organized by mid-2012 as a number of these experimental units are still in operation. The most notable include:

-

Free Police in Aleppo and Idlib

-

Police Command in Eastern Ghouta

-

Police Command in Eastern Qalamun and Badia

-

Police Experiment in Homs (internal security)

While there are many experimental units that operate under various names (such as the Maintaining Order Forces, the Revolutionary Outposts, Public Security, Security Councils, and the Judicial Police, there remain local experimental units that never developed a clear institutional structure that went beyond their sectors or regions.

Second: Local Judiciary

In the absence of courts operated by the state judiciary, alternatives have emerged that differ with regards to legal authority, formation mechanisms, work methods, and the nature of jurisdiction and subordination. These include:

-

High Judicial Council in Aleppo

-

Islamic Commission Courts for the Administration of Liberated Areas

-

Judiciary Council in Eastern Ghouta

-

Courthouse in Horan

-

High Court in the Northern Homs Countryside

-

Fateh al-Sham (al-Nusra) Front Courts (previously called Courthouses)

Third: Faction Security Bureaus

From their inception, opposition military factions have formed miniature Security Committees that are tasked with gathering and analyzing information and compiling a list of goals to be worked towards. These experimental committees continued to develop and were placed within the framework of Security Bureaus housed within the structure of the opposition factions themselves. These bureaus can be placed into four categories:

-

Armed Opposition Faction Security Bureaus, including: al-Jabha al-Shamiyya, Jaysh al-Mujahidin, Nur ad-Din Zengi, Rahman Corps, Southern Front Factions, Jaysh al-Nasr, and the Authenticity and Development Front.

-

National Islamic Faction Security Bureaus, including: Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiyya, Army of Islam, and Sham Legion.

-

Security Bureaus Arising from Military Alliances, including: Army of Conquest’s Executive Power, Free Idlib Army’s Security Bureau, Descendants of Hamza and Abu Amara Brigades’ Joint Security Bureau, and the Homs Operations Room.

-

Supranational Jihadist Faction Security Bureaus, such as Jabhat Fateh al-Sham.

Evaluating Security Work in Areas Held by the Armed Opposition

Decentralization is the dominant feature of security administration in areas held by armed rebel factions. This is due to there being no central reference point for administering security. The decentralized security authorities lack institutional character for the following reasons:

-

Multiplicity of authorities: This leads to the creation of conflicting functions, clashing interests, and a lack of both consistency and integration.

-

Lack of manpower and specialized skills.

-

Lack of equipment and logistical support.

-

Lack of strategic planning.

The escalation of chaos in Syria’s rebel-held areas stems not only from a lack of institutionalization and limited capabilities, but also from an increase in threats from rebel opponents. Indeed, there are signs that the security situation in these areas is only growing worse, as indicated by the rise in assassinations and explosions, as well as the increase in criminal activities, such as theft, looting, robbery, and crimes against public decency. This bleak picture is further bolstered by the persistence of detainment, forced disappearances, torture, and the spread of armed gangs, drug dealers, smugglers, and the sale of stolen merchandise. The experimental security units outlined above assume a critical role in both curbing the retreat of viable security mechanisms and fighting terrorist groups, such as ISIS, particularly Aleppo, Rif Dimashq, and Qalamun. This is apparent in their relentless efforts to institutionalize and codify their operations through ongoing coordination with local councils, which are more representative and legitimate than other governing bodies.

Third: The Security Structure in “Administratively Autonomous” Areas

The occupations of security personnel in administratively autonomous areas closely resemble analogous position in regime-held areas before the uprising. Both sets of occupations subscribe to a model of community policing that is commensurate with the political ideology of the ruling party, condones the legitimacy of political detention and community militarization, and that links security directives to the central governing authority. However, Syria’s security establishment suffers from deep conflicts within its institutions as well as duplicity among authorities spread out between regime- and Democratic Union Party (PYD)-controlled areas. Perhaps the greatest danger threatening public security is the PYD’s ideological connection with military and security branches and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which is both separatist and hostile to neighboring countries.

With the outbreak of the uprising, the PYD formed organized cells, some of which were structured as units called the “Revolutionary Youth Movement” led by Xebat Derik, a former commander in the PKK who was affiliated with a number of its institutions and was the first commander of the People’s Protection Units. With the development of the conflict, the PYD’s military and security organizations proliferated, some of which include.([3])

1. People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units

These units rely on volunteer forces and lead major military operations in rural and urban areas that the PYD seeks to gain control of. The general structure of the YPG’s military hierarchy’s is comprised of a general command leadership, followed by a military council and field commanders drawn from different brigades, companies, and regions. In the past, the units’ military legitimacy rested on Article 15 of the “Charter of the Social Contract for Autonomous Democratic Rule” (ratified in the PYD’s first session on 01/06/2014), which states that the YPG comprise the only national institution responsible for defense and the preservation of both territorial sovereignty and peace in provincial lands. Moreover, the YPG serves the interests of the people by defending their objectives and national security. It is estimated that the number of fighters serving in the YPG ranges between 20,000 and 30,000.

2. Self-Defense Forces (HPX)

The Social Contract also ratified the formation of the Self-Defense and Protection Authority on 01/21/2014. Later, on 07/13/2014, the Legislative Council approved the Self-Defense Law, which states that each family is obliged to put forth one of its family members between the ages of 18 and 30 to perform “self-defense duty” lasting six months (nine months as of January 2016). The authority’s mission is to implement laws pertaining to the mandatory conscription of Kurds and is carried out by the PYD in areas under its control. Meanwhile, groups allied with the PYD, such as al-Sanadid Forces formed by the Shammar tribe, implement the policy in their own areas.

3. Core Defense Forces (HPC)

These forces draw their missions and duties from the needsof the autonomous Kurdish region by protecting areas and neighborhoods from attacks. For instance, they set up checkpoints on the main roads leading into neighborhoods, gather information about suspicious individuals in the area, support the People’s and Women’s Protection Units in combat operations, and coordinate with Asayish forces and other security services active in the area.

4. Asayish Internal Security Organization – Rojava

Subordinate to the General Authority, this group operates in al-Jazira and Kobani Provinces under the joint leadership of Commanders Jawan Ibrahim and Ayten Farhad. In the approximately four years since its inception, Asayish has developed the public security services in Rojava by leaps and bounds, now carrying out all security duties and possessing security apparatuses that carry out a multitude of functions. These include the: Traffic Directorate (tirafik), Anti-Terror Forces (HAT), Women’s Asayish, Checkpoints Administration, Public Security Directorate, and Organized Crime Directorate. By the end of 2016, the Public Security Directorate possessed 45 centers, 21 of which were located in al-Jazira, 5 in Kobani, 19 in Afrin, as well as over 195 permanent checkpoints throughout Rojava. There are 4,000 to 5,000 personnel and operatives serving in these different apparatuses.

There are other reserve forces as well, the most important including the Internationalist Freedom Brigade and an assortment of western advisors, which were formed because of the influx of foreign personnel to join the YPG after the battle against ISIS in Kobani. On 06/10/2015 the 25-person brigade officially announced its establishment in Ras al-Ayn (Sere Kaniye) and attracted foreign personnel of various nationalities, however most were Turkish leftists from the Marxist-Leninist Communist Party (MLKP) of Turkey, PKK, Villagers for Turkey’s Salvation (which is the military branch of the MLKP that dates back to 1973), and individuals from Eastern European leftist movements. At this time, a number of organizations began to form and were filled by newly arrived operatives to Rojava. At this time, the brigade divided into two parts: the Bob Crow Brigade (BCB), after the British union leader, and the Henri Krasucki Brigade, after the French communist leader. The Internationalist Freedom Brigade is led by a 30-year-old Kurdish woman named Deniz and is comprised of approximately 200 to 300 fighters.

The western presence in the Kurdish territories is not limited to volunteer fighters, but also includes a sizeable number of advisors who initially came to train YPG fighters, but went on to train the Syrian Democratic Force (SDF) as well. These advisors include French, Americans, as well as a small number of Brits, nearly 500 of which direct the international coalition’s airstrikes against ISIS. The PYD is a strategic ally of the United States and, as their relations have developed, the latter has constructed five or six military bases in the outskirts of the oil city of Rmeilan, Mabrouka in western Qamishli, Tell Beydar in the northern outskirts of Hasakah, as well as a base headquarters near Ayn Issa and a base for American forces in the former French Lafarge cement factory.

Fourth: Security Fundamentals and Imperatives

The general unraveling of the security establishment in Syria clues us in to some of the fundamental forces that will act upon the shape of the future public security apparatuses in the country. These include:

-

Differences in political, ideological, and military terms of references.

-

International actors’ inconsistency in supporting the security services.

-

Disparities in political projects and ambitions pertaining to security.

-

Inability of any centralized government to regulate security services using integrated mechanisms because of the highly decentralized nature of the services.

-

Additional hidden security threats will surface the moment that a political transition occurs that does not take into account the nature of Syria’s security situation.

-

Inadequacy of the characterization that regions under regime political control have a coherent security structure.

-

Doubt in the regime’s ability to reign in the security establishment.

-

Increase in security threats throughout Syria.

-

Need for the security transformation process to be consistent with data on the public security situation.

-

Various and conflicting regional and international security breaches.

The Primary Arrangements Needed to Build an Integrated Security Sector

This refers to the group of measures and arrangements needed to transition from a less fluid security system to one that is more disciplined and in line with a central security strategy. The following recommendations speak to these needs:

-

Implement a group of constitutional principles that outline the new security doctrine’s adherence to the concept of administrative decentralization, link security to the nation and its citizenry, and put an end to the security services’ interference in politics.

-

Expel all foreign militias from Syria under the pretenses that they represent a real security threat.

-

Have international and regional actors agree to support security stability, organize with the central government, and offer up the expertise and support needed to develop security service manpower.

-

Dissolve all local militias and hand their weapons over to the state as a strategic necessity. Otherwise, have the security services regulate the security performance of these militias by enforcing codes of conduct and the security objectives expected of them. This can include a timetable for handing over arms and disbanding militias.

-

Adopt political measures needed for changing the security establishment while emphasizing the necessity of integration.

-

Have the state adopt governance programs for security work in Syria.

From here, the following points must be emphasized:

-

Dispatch the state security force in an organized fashion throughout regions out of the regime’s control to carry out all security duties, except those related to sovereignty.

-

Integrate all anti-terrorism personnel.

-

Link successful policing experiments institutionally to local governments, particularly in opposition-held areas and the Suwayda Governorate.

-

Put an end to all prevailing legal authorities and bind them to a unified model produced by the state in accordance with the new constitution.

-

Archive security operations in all regions according to a special archive system.

-

Emphasize the necessity that civil society supports, oversees, and protects the transition process.

-

Turn all military apparatuses into local operational security mechanisms that are administratively subordinate to the Ministry of Interior, but granted a high degree of independence.

-

Strengthen the concept of local empowerment by having locals supervise and implement the security plan, carry out security tasks, and maintain their area’s unique character.

-

Issue a general law that organizes the security agenda’s goals and limits. This will also define the security apparatuses’ relation to the central security establishment and oblige security personnel to adhere to the policies both contained within the resolution on Syria’s independence and that guard against fragmentation and division.

-

Ensure that financial, oversight, and administrative policies are consistent with the concepts of administrative decentralization.

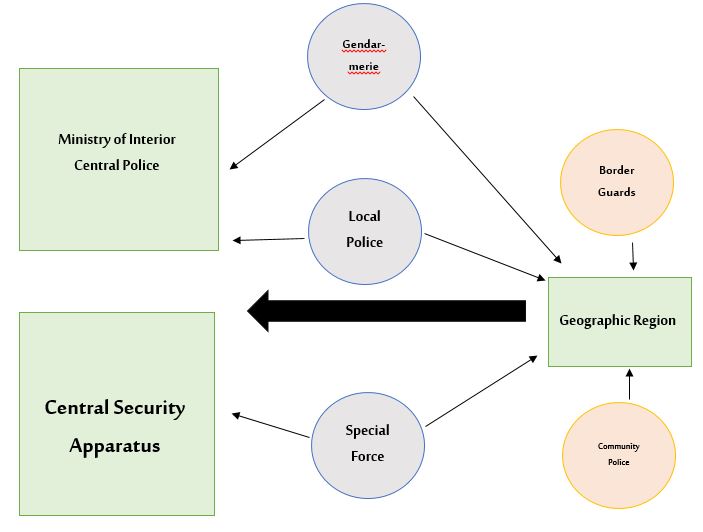

The Figure Below Clarifies the First Recommendation Regarding Sectoral Security Functions:

1. Regional Functions

These are functions granted by the central authority of each geographic region that distribute security forces:

-

Border Guards: These local military units are concerned with border control and crossing.

-

Gendarmerie: These local military units deal with organized crime, smuggling, and gangs.

-

Community Police: These units specialize in community policing and are made up of trained civilian personnel that carry out functions derived from the unique local circumstances of each community.

-

Local Police: While administratively and structurally subordinate to the Ministry of Interior, these units are supervised by local units (Local Councils), which also appoint its staff according to set regulations.

-

Special Force: This unit is integrally related to the central security apparatus and functions as its executive military wing in anti-terrorism operations.

2. Central Security Functions

These relate to security breaches, anti-terrorism, gathering security information and providing it to competent authorities, preserving stability, ensuring law enforcement, and following up on security operations in all districts via legally-regulated relations with local units.

([1]) Maen Tallaa, Power of security centers at the Regime, part of the unpublished research in Omran Center for Strategic Studies, January 2017.

([2])Ayman-Al Dassouky, a study entitled: local councils and local file security: Required Role for a problematic file, a study issued by Omran Center for Strategic Studies, 20 January 2017, Link: https://goo.gl/K9RzKM

([3]) Bader Mulla Rashid, Security infrastructure in SDF/YPG controlled Areas, unpublished paper from Omran Center for Strategic Studies, January 2017