Why Reports of ISIS’ Demise Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

During the same week the U.S. and Russia declared victory over ISIS in Syria, the militant group launched a series of surprise attacks around the country. Despite the triumphant claims of world leaders, these offensives suggest such statements are a little premature.

The same day that President Vladimir Putin declared victory over the so-called Islamic State, the militant group launched a surprise offensive against government forces in Deir Ezzor province, killing up to 31 pro-government fighters in the following three days.

“In just over two years, Russia’s armed forces and the Syrian army have defeated the most battle-hardened group of international terrorists,” Putin told Russian forces on Monday during a visit to Russia’s Hmeimim air base in Syria, before ISIS attacked government positions north of the town of Boukamal, a former key stronghold for the militants.

U.S. President Donald Trump made similar victory claims on Tuesday while signing the National Defense Authorization Act into law. The bill, he said, “authorizes funding for our continued campaign to obliterate ISIS. We’ve won in Syria … but they [ISIS] spread to other areas and we’re getting them as fast as they spread.”

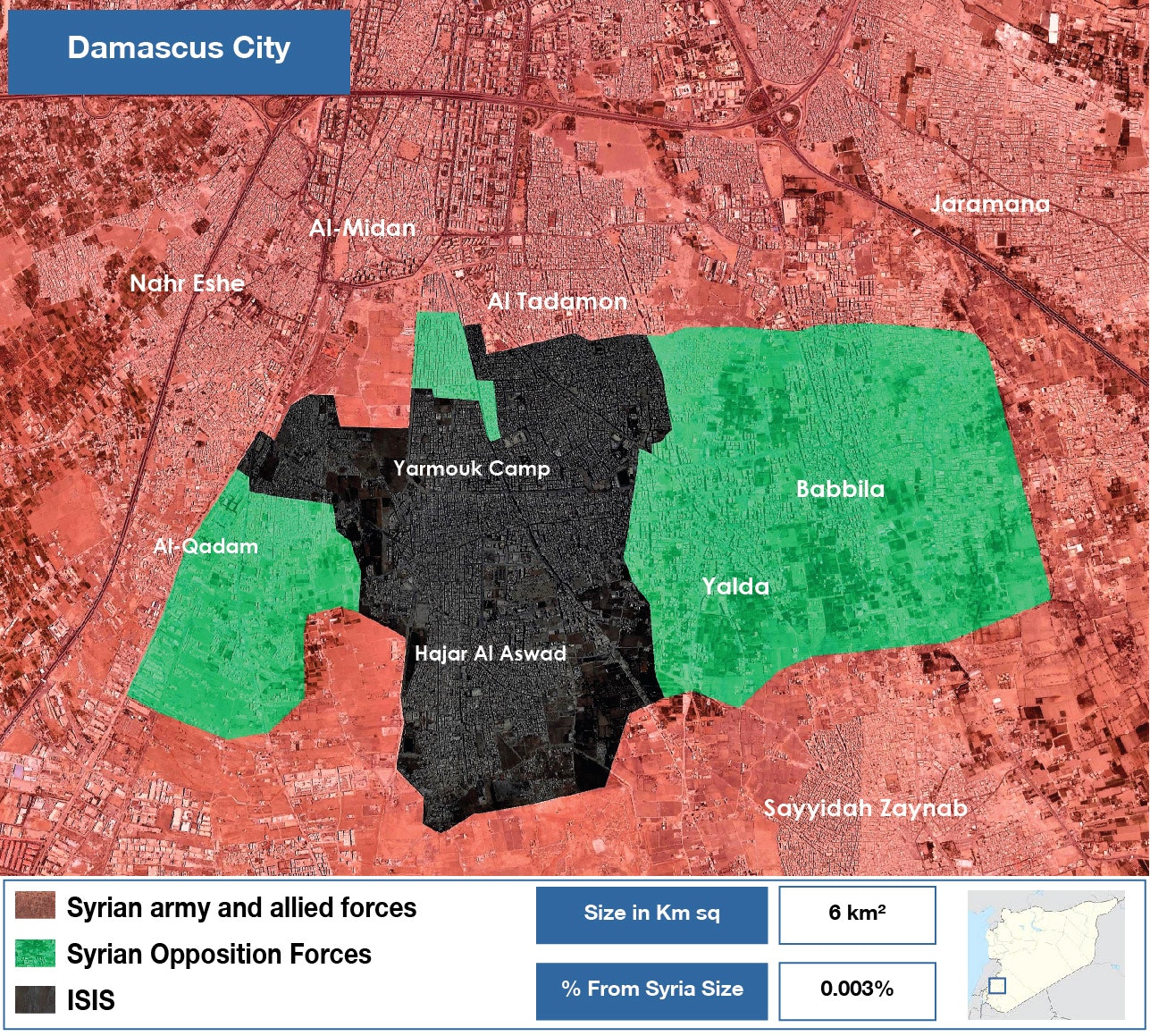

The following day, however, ISIS militants engaged in clashes with a Pentagon-backed rebel group near a U.S. base in al-Tanf in southwest Syria. Militants near the Palestinian Yarmouk camp south of Damascus also launched an attack on government positions in the nearby al-Tadamon neighborhood, seizing 12 buildings. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights described it as the largest offensive south of the capital “in months.”

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS south of the Syrian capital, Damascus.

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS south of the Syrian capital, Damascus.

By Omran for strategic studies -Nawar Oliver

While it’s unclear if ISIS timed the attacks as a response to the U.S. and Russian statements, the militant’s new offensives serve as a reminder that it may be too soon to sound the death knell for ISIS in Syria, experts said.

At the height of its power in 2015, ISIS commanded territory in Iraq and Syria larger than the size of Ireland. This year, however, separate Russian and U.S. military campaigns pushed militants out of all their major strongholds across the two countries. While Putin and Trump call this a complete defeat others remain skeptical.

“I think that there’s a bit of ambiguity and confusion with regard to what a defeat might look like,” Simon Mabon, a lecturer in international relations at Lancaster University and co-author of The Origins of ISIS, told Syria Deeply.

“Whilst some will talk of a military defeat and the liberation of Syrian-Iraqi territory, the bigger and arguably much trickier struggle is about defeating the ideology and preventing the group – or a manifestation of it – from re-emerging,” Mabon said.

Earlier this month, Sergei Rudskoi, a senior Russian military officer claimedthat “not a single village or district in Syria under the control of ISIL.”

According to the SOHR, ISIS still controls 3 percent of Syrian territory, or 5,600 square kilometers (2,162 square miles). ISIS is present in southern Damascus, in “large parts” of the Yarmouk camp as well as in parts of the al-Tadamon and al-Hajar al-Aswad neighborhoods, where they are battling government forces.

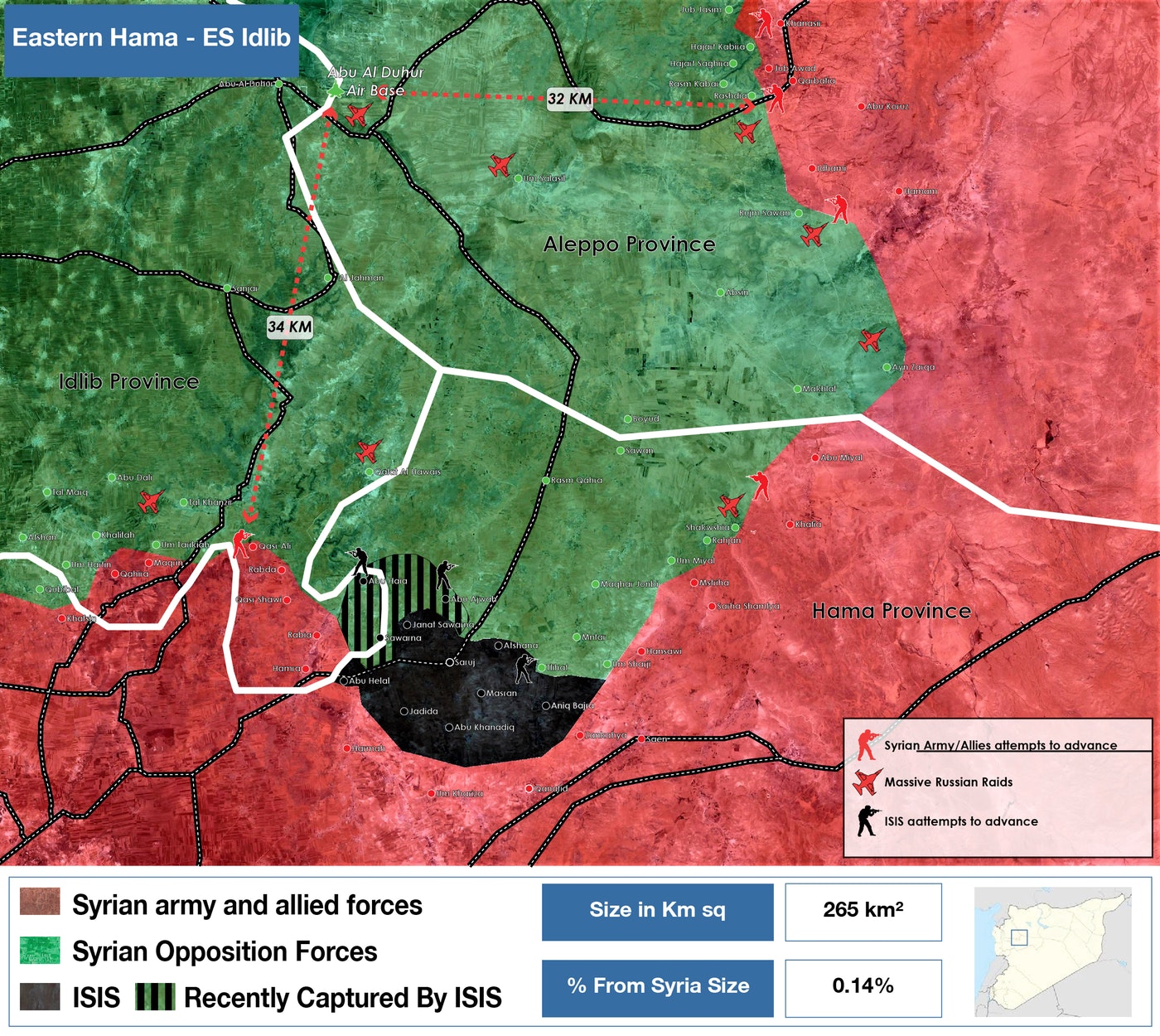

ISIS is also active in desert regions east of the government-held town of Sukhana in Homs province as well as in a small enclave in northeast Hama, where it is engaged in fighting with the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham alliance.

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS in Hama province.

By Omran for strategic studies -Nawar Oliver

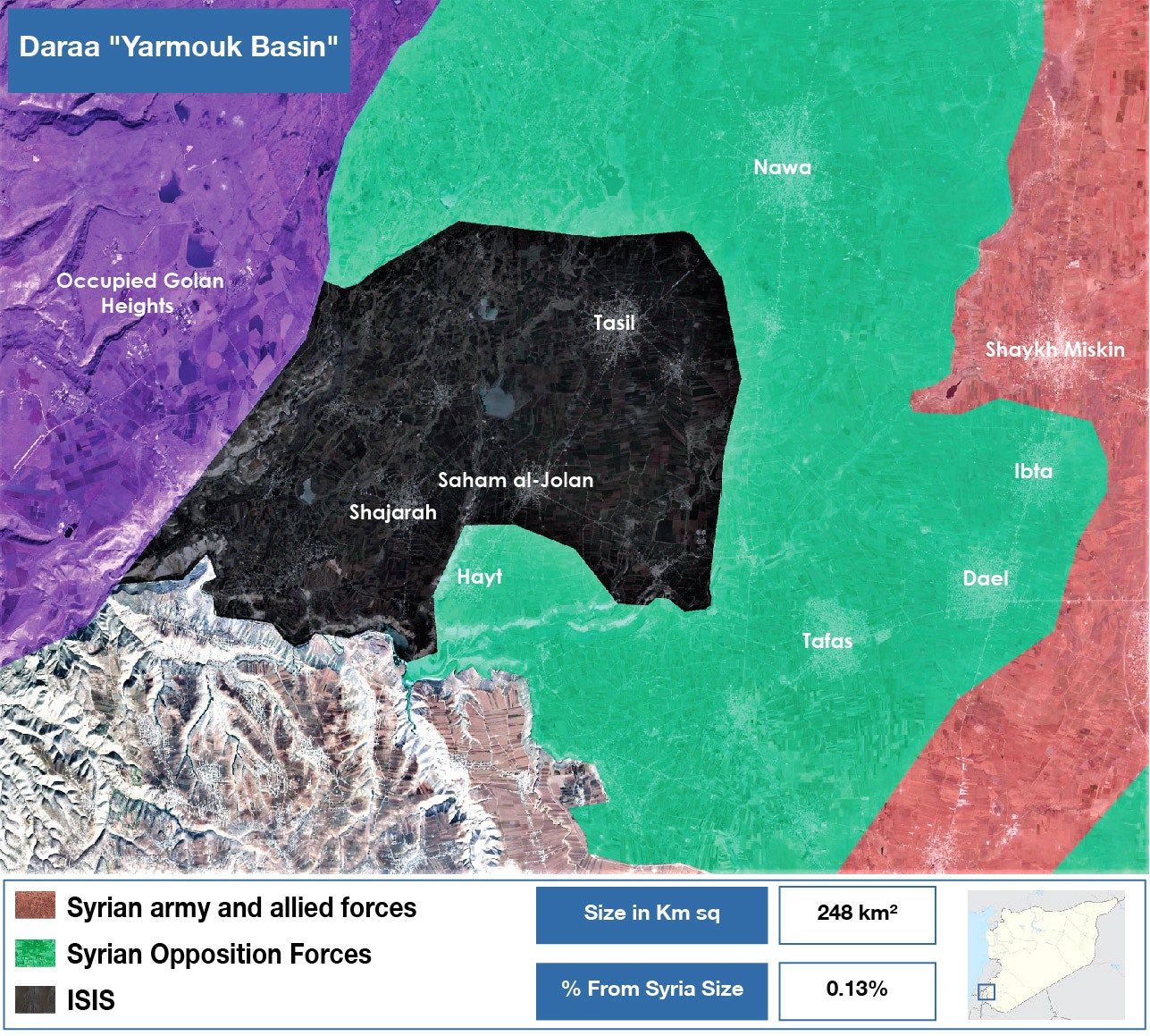

Militants also control at least 18 towns and villages in Deir Ezzor province, where it is battling both the Syrian government and the U.S. backed Syrian Democratic Forces. In Syria’s southern province of Daraa, ISIS controls a small enclave close to the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, where it has previously clashed with rebel forces.

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS in the southern province of Daraa.

By Omran for strategic studies -Nawar Oliver

Some White House staff and French President Emmanuel Macron said they were wary of Russia’s claim of victory on the ground. “We think the Russian declarations of ISIS’ defeat are premature,” an unidentified White House National Security Council spokeswoman told Reutersin a report published Tuesday.

“We have repeatedly seen in recent history that a premature declaration of victory was followed by a failure to consolidate military gains, stabilize the situation, and create the conditions that prevent terrorists from reemerging,” she said.

The militant’s last vestiges of territory are coming under severe strain by a wide array of rivals. It is only a matter of time before militants are driven to rugged hideouts in Homs and in the Euphrates Valley region. But as military battles subside across the country, a slow-grinding and methodical campaign should kick off to prevent an ISIS resurgence.

“To properly talk of a victory over the group, the conditions that gave rise to them must be eradicated. By that, I mean that people must improve their living conditions, be granted better access to political structures and to be able to exert their agency in whatever way they wish,” Mabon said.

“To fully defeat ISIS, such conditions must be addressed, preventing grievances from emerging that force people to turn to groups such as ISIS as a means of survival,” he added.

However, with military operations against militants still underway, there has yet to be any significant attempt to battle the ideological residues of the group or address the grievances that led to its emergence.

In an attempt at countering ISIS’ ideology, activists and Islamic scholars set up the Syrian Counter Extremism Center (SCEC)in the countryside of Aleppo in October. However, the so-called terrorist rehabilitation center has limited funding, giving it little ability to prevent the return of ISIS, especially after hundreds of ISIS-affiliated militants and defectors flocked to opposition-held areas in northern Syria in recent months.

Iraq, whose military also declared victory over ISIS this month after driving militants from their major strongholds, is already confronting a possible return of the extremist organization, in a further indication that claims of victory are premature.

According to the Iraq Oil Report, a new armed group, hoisting a white flag that bears a lion’s head, has recently appeared in disputed territories in northern Iraq. Citing local leaders and Iraqi intelligence, the report claimed that some members of the new group are known to have been members of ISIS. This has given rise to fears that ISIS may be “regrouping and rebranding for guerrilla warfare,” the report said.

A regrouping of ISIS would not come as a surprise, especially since militants can still capitalize on grievances in marginalized Sunni communities across Iraq and Syria.

“Across both states, Sunnis had been persecuted and marginalized, politically and economically, along with the physical threat to their very survival,” Mabon said.

“Whilst many are fearful and angry of ISIS, the deeper issues of marginalization and persecution remain.”

Russia’s Brittle Strategic Pillars in Syria

With unreliable allies and a lack of experience with local power dynamics, Russia’s influence in Syria is built on fragile foundations

With political control fragmented among local powerbrokers in Syria, Russia’s overreliance on the Assad regime to protect its interests is a strategic threat. Despite current intersecting interests, neither the regime nor its Iranian allies are reliable partners. Competing and conflicting interests may finally come to a head once a political solution begins to take shape and Syria embarks on reconstruction, particularly in light of new regional arrangements.

Belying Vladimir Putin’s claim during his surprise visit to Syria that Russia is pulling back, these factors have in fact driven Russia to work to develop new tools that will enable it to maximize its gains and safeguard its interests in Syria.

Russian strengths and weaknesses

Russia reportedly has seven military bases housing approximately 6,000 individuals in Syria, and an estimated 1,000 Russian military police spread throughout the de-escalation zones and areas recently reclaimed from the opposition as a result of reconciliation agreements. Russia has also entrusted several private security forces with the task of carrying out special missions ostensibly in its war against ISIS and with protecting Russian energy installations and investment projects; these include the paramilitary group, ChVK Vagner, which, according to sources, has around 2,500 individuals on the ground in Syria.

But Russia realizes that it is not strong enough to guarantee its interests in Syria on its own and that it must rely on local partners to do so. Hence, Moscow is making efforts on two separate fronts. One is vertical – aiming to establish lasting influence within state institutions, particularly the military and security apparatus – by investing in influential decision makers, such as General Ali Mamlouk, director of the Baath Party’s National Security Bureau, and General Deeb Zeitoun, head of Syria’s General Intelligence Directorate, two of the most prominent security men.

The other is horizontal in nature. Russia is keen to develop relationships with local powerbrokers directly in order to build inroads with local communities with a view to balancing Iran’s growing influence within Syrian society. These relationships could be used as leverage to sway political negotiations towards Russian interests, while also recruiting them as local partners and guarantors for Russian investments.

Reaching out

The Russian Reconciliation Centre for Syria at Hmeimim Airbase plays a key role in communications with local powerbrokers; however, the communication mechanism and those responsible for it vary according to who controls the relevant areas. In coordination with the National Security Bureau, Russia has been able to engage with local powerbrokers in regime-controlled areas, including various political parties, local dignitaries and religious and tribal leaders, through Reconciliation Centre staff. It has also been able to communicate with the Kurds via military and security channels like Hmeimim Airbase and the Russian Ministry of Defence or via political channels managed by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in coordination with Hmeimim.

But Russia faces a dilemma communicating with local powerbrokers in opposition controlled areas and dealing with the influence of multiple regional actors. To overcome those challenges, it has employed several mechanisms to communicate with these groups in an attempt to co-opt them, using important political figures such as Ahmad Jarba to communicate with local leadership in besieged areas like Homs and Eastern Ghouta, and resorting to local reconciliation committees (primarily made up of local dignitaries and technocrats associated with the regime) that possess their own communication channels that can be used to communicate with the local opposition, as was the case in Al-Tel shortly before the Free Syrian Army’s withdrawal.

According to an activist from northern Homs, Russia is also very much dependent on cadres of Chechen Muslim military police, fluent in Arabic, to communicate with local leaderships. In addition, Moscow has used Track II diplomacy to network with local powerbrokers and open up back channels through relationships with regional powers.

Russia has so far employed the ‘carrot and stick’ model when communicating with local powerbrokers to ensure its influence, offering up benefits like security protection and financing, while guaranteeing them a place at the negotiating table and a share of reconstruction revenue. But based on past form, more heavy-handed measures to pressure local powerbrokers, such as making them targets of future military operations or playing on local rivals to marginalize or giving preference to one group over another in a political solution and reconstruction arrangements, remain on the table.

Enduring challenges

Although it has made strides stabilizing its military presence and legitimizing its security arm in Syria, Russia still faces challenges generating leverage within state institutions and Syrian society where Iran opposes Russia's efforts. The regime’s many centres of power, reliance on militias and weak institutions limit Russia’s efforts to consolidate its influence in the rest of Syria. Similarly, Moscow is finding it difficult to communicate with Syria’s many powerbrokers and differentiate between their demands, references and allegiances to other regional powers – making Russia’s strategic pillars in Syria all the more fragile.

Al-Qaeda Affiliate and Ahrar al-Sham Compete for Control in Idlib

"This special report was published byMiddle East Institute , in collaboration with Omran for Strategic Studies, andOPC- Orient Policy Center"

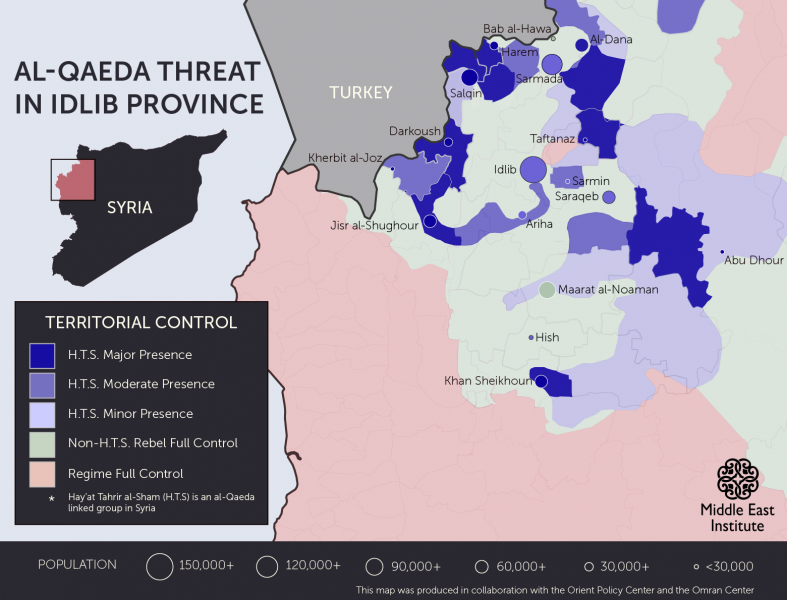

Idlib is currently the site of increasing competition between the two most dominant armed coalitions, the al-Qaeda-linked Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (H.T.S.) and Ahrar al-Sham. The province has witnessed limited airstrikes since a de-escalation agreement, which came into effect on May 5, was brokered by Russia, Turkey, and Iran at the Astana talks. Idlib was one of four areas labeled as a de-escalation zone.

The agreement has, however, prompted a contest between H.T.S. and Ahrar al-Sham, with both groups vying to increase their influence and control new areas. The competition between them has three dimensions: military, economic, and social.

For strategic, economic, and military reasons, H.T.S. has focused efforts on controlling vital towns, specifically along the Syrian-Turkish border on the western side of the province. H.T.S. fighters that shifted to the region from losses in Aleppo and Homs were deployed carefully in areas where the al-Qaeda affiliate wanted to increase influence, particularly along the northwestern border.

The “smuggling” route along the border from Harem to Darkoush is totally controlled by H.T.S., which uses it to transport oil and other goods. The mountainous nature of the area and its many caves also allow H.T.S. to thwart any attack or attempts by Ahrar or any other group to assert control in those territories.

Though H.T.S. controls military bases in the area, such as Taftanaz, to the northeast of Idlib, and Abu Dhour, southeast of Idlib, the group faces challenges in governance. Lacking communal support and strong governing skills, H.T.S. can’t fully control major cities like Idlib, Maarat al-Noaman, and Saraqib. Even in smaller towns like Kafranbel, where civil society has been active, H.T.S. has also failed to maintain a tight grip.

The experience of Maarat al-Noaman is an example of how local communities have played a major role in confronting H.T.S. Since February 2016, civil society has actively mobilized against al-Qaeda’s presence, first against Jabhat al-Nusra, as they were called at the time, and later against present-day H.T.S. The group was unable to control the city or defeat armed opposition groups largely due to the local community’s support for the armed groups. “It is not the armed groups there that protected civil society and the local community, it’s the community that prevented H.T.S. from defeating the armed opposition inside the city,” said Basel al-Junaidy, director of Orient Policy Center.

The only large city H.T.S. has been able to control is Jisr al-Shughour, in part because the armed groups surrounding the city are loyal to Abu Jaber, the former leader of Ahrar al-Sham who defected to H.T.S. earlier this year.

Following increasing pressure from Turkey to protect its borders, H.T.S. delegated to Ahrar al-Sham control over parts of the northwestern border near the town of Salqin. However, H.T.S. still enjoys influence there, and Ahrar still needs H.T.S. approval to appoint the leader of the group assigned to watch the border in that area.

Yet the current map could also be misleading. There are areas where H.T.S. has presence, but struggles to maintain control, and there are areas where it does not yet have a presence, but could expand power if threatened. For example, the main border crossing between Idlib and Turkey is Bab al-Hawa. It is controlled by Ahrar al-Sham, but H.T.S. controls the route leading to the crossing through several checkpoints, and has the capability to attack the border crossing and seize control at will.

In the north, Sarmada is becoming the economic capital of Idlib. H.T.S. controls most of the decision-making there with regards to regulations like money transfers, the exchange rate, and the prices of commodities like metal and oil. On the other hand, H.T.S. is weakest in southern Idlib, from the borders of the Hama province to Ariha, the social base for Ahrar al-Sham.

H.T.S. governs through its General Directorate of Services, which competes with several other entities to provide services. These competitors include Ahrar al-Sham’s Commission of Services, local councils under the umbrella of the opposition interim government, independent local councils, and civil society organizations. A recent study conducted by the Omran Center shows that there are 156 local councils in the province of Idlib; 81 of them are in areas where H.T.S. has a strong presence. As highlighted above, however, H.T.S. doesn’t enjoy equal control over all of these councils. While in some instances the group has comprised whole councils—as in Harem, Darkoush, and Salqin—in other councils, H.T.S. is only able to influence some members.

Due to the de-escalation zones agreement, H.T.S. currently finds itself in a challenging position. When the Nusra Front established its presence in Syria, it promoted itself as the protector of the people. Escalating violence helped the group gain legitimacy and sympathy, and many armed groups found a strong ally in the al-Qaeda affiliate as battles raged against the regime. As front lines become quieter, H.T.S. is beginning to lose its appeal.

The H.T.S. alliance also faces internal threats. The dynamics are changing between Nusra and the Nour al-Din al-Zenki movement, the second largest component of H.T.S. On June 2, Hussam al-Atrash, a senior leader of Zenki, tweeted that areas out regime control should be handed over to the opposition interim government, and all armed groups should dissolve. Atrash justified his suggestion as the only way for the Sunni armed opposition forces to survive. The comments irritated H.T.S. leadership, which referred Atrash to the H.T.S. judiciary. The tweets disappeared shortly thereafter.

Following that incident, H.T.S. banned all fighters from mentioning any subgroup names, like Zenki, to enforce unity. However, it is unlikely that H.T.S. will be able to maintain long-term enforcement. No opposition military alliance has been able to survive throughout the Syrian conflict, and subgroups continue to migrate from one umbrella to another for tactical reasons, seeking military protection and/or new funding opportunities.

While H.T.S. faces these internal and external challenges, it is also evolving. Its leadership clearly realized the importance of building stronger connections with local communities in order to compete with Ahrar al-Sham. H.T.S. adopted new tactics in governing. Instead of appointing foreigners or military leaders, H.T.S. has appointed local civilians as its representatives in most of the towns under its control in Idlib.

H.T.S. and Ahrar will continue to compete in governance and service provision, which is key to building loyalty, increasing influence, and widening public support. The groups are also cautiously following regional and international developments as they prepare for different scenarios. If the de-escalation agreement collapses or an external force intervenes in Idlib, all dynamics will certainly change. Ahrar and H.T.S. might confront each other, become allies, or re-shuffle their respective coalitions. The situation in Idlib is far from stable.

TRT World Interview with Ammar Kahf about on the latest in Aleppo

Dr. Ammar Kahf Talks about on the latest in Aleppo

TRT World Interview with Ammar Kahf about cessation deal reached by US and Russia

Dr. Ammar Kahf Talks about cessation deal reached by US and Russia

Geopolitical Realignments around Syria: Threats and Opportunities

Abstract: The Syrian uprising took the regional powers by surprise and was able to disrupt the regional balance of power to such an extent that the Syrian file has become a more internationalized matter than a regional one. Syria has become a fluid scene with multiple spheres of influence by countries, extremist groups, and non-state actors. The long-term goal of re-establishing peace and stability can be achieved by taking strategic steps in empowering local administration councils to gain legitimacy and provide public services including security.

Introduction

Regional and international alliances in the Middle East have shifted significantly because of the popular uprisings during the past five years. Moreover, the Syrian case is unique and complex whereby international relations theories fall short of explaining or predicting a trajectory or how relevant actors’ attitudes will shift towards the political or military tracks. Syria is at the center of a very fluid and changing multipolar international system that the region has not witnessed since the formation of colonial states over a century ago.

In addition to the resurrection of transnational movements and the increasing security threat to the sovereignty of neighboring states, new dynamics on the internal front have emerged out of the conflict. This commentary will assess opportunities and threats of the evolving alignments and provide an overview of these new dynamics with its impact on the regional balance of power.

The Construction of a Narrative

Since March 2011, the Syrian uprising has evolved through multiple phases. The first was the non-violent protests phase demanding political reforms that was responded to with brutal use of force by government security and military forces. This phase lasted for less than one year as many soldiers defected and many civilians took arms to defend their families and villages. The second phase witnessed further militarization of civilians who decided to carry arms and fight back against the aggression of regime forces towards civilian populations. During these two phases, regional countries underestimated the security risks of a spillover of violence across borders and its impact on the regional balance of power. Diplomatic action focused on containing the crisis and pressuring the regime to comply with the demands of the protestors, freeing of prisoners, and amending the constitution and several security based laws.

On the other hand, the Assad regime attempted to frame a narrative about the uprising as an “Islamist” attempt to spread terrorism, chaos and destruction to the region. Early statements and actions by the regime further emphasized a constructed notion of the uprising as a plot against stability. The regime took several steps to create the necessary dynamics for transnational radical groups (both religious and ethnic based) to expand and gain power. Domestically, it isolated certain parts of Syria, especially the countryside, away from its core interest of control and created pockets overwhelmed by administrative and security chaos within the geography of Syria where there is a “controlled anarchy”. It also amended the constitution in 2012 with minor changes, granted the Kurds citizenship rights, abolished the State Security Court system but established a special terrorism court that was used for protesters and activists. The framing of all anti-regime forces into one category as terrorists was one of the early strategies used by the regime that went unnoticed by regional and international actors. At the same time, in 2011 the regime pardoned extremist prisoners and released over 1200 Kurdish prisoners most of whom were PKK figures and leaders. Many of those released later took part in the formation of Jabhat al-Nusra, ISIS, and YPG forces respectively. This provided a vacuum of power in many regions, encouraging extremist groups to occupy these areas thus laying the legal grounds for excessive use of force in the fight against terrorism.

The third phase witnessed a higher degree of military confrontations and a quick “collapse” of the regime’s control of over 60% of Syrian territory in favor of revolutionary and opposition forces. Residents in 14 provinces established over 900 Local Administration Councils between 2012 and2013. These Councils received their mandate and legitimacy by the consensus or election of local residents and were tasked with local governance and the administration of public services. First, the Syrian National Council, then later the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces were established as the official representative of the Syrian people according to the Friends of Syria group. The regime resorted to heavy shelling, barrel bombing and even chemical weapons to keep areas outside of its control in a state of chaos and instability. This in return escalated the level of support for revolutionary forces to defend themselves and maintain the balance of power but not to expand further or end the regime totally.

During this phase, the internal fronts witnessed many victories against regime forces that was not equally reflected on the political progress of the Syria file internationally. International investment and interference in the Syrian uprising increased significantly on the political, military and humanitarian levels. It was evident that the breakdown of the Syrian regime during this phase would threaten the status quo of the international balance of power scheme that has been contained through a complex set of relations. International diplomacy used soft power as well as proxy actors to counter potential threats posed by the shifting of power in Syria. Extremist forces such as Jabhat al-Nusra, YPG and ISIS had not yet gained momentum or consolidated territories during this phase. The strategy used during this phase by international actors was to contain the instability and security risk within the borders and prevent a regional conflict spill over, as well as prevent the victory of any internal actor. This strategy is evident in the UN Security Council Resolution 2042 in April 2012, followed by UNSCR 2043, which call for sending in international observers, and ending with the Geneva Communique of June 2012. The Geneva Communique had the least support from regional and international actors and Syrian actors were not invited to that meeting. It can be said that the heightened level of competition between regional and international actors during this phase negatively affected the overall scene and created a vacuum of authority that was further exploited by ISIS and YPG forces to establish their dream states respectively and threaten regional countries’ security.

The fourth phase began after the chemical attack by the regime in August of 2013 where 1,429 victims died in Eastern Damascus. This phase can be characterized as a retreat by revolutionary military forces and an expansion and rise of transnational extremist groups. The event of the chemical attack was a very pivotal moment politically because it sent a strong message from the international actors to the regional actors as well as Syrian actors that the previous victories by revolutionary forces could not be tolerated as they threatened the balance of power. Diplomatic talks resulted in the Russian-US agreement whereby the regime signed the international agreement and handed over its chemical weapons through an internationally administered process. This event was pivotal as it signified a shift on the part of the US away from its “Red Line” in favor of the Russian-Iranian alignment, which perhaps was their first public assertion of hegemony over Syria. The Russian move prevented the regime’s collapse and removed the possibility of any direct military intervention by the United States. It is at this point that regional actors such as Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia began to strongly promote a no-fly zone or a ‘safe zone’ for Syrians in the North of Syria. During this time, international actors pushed for the first round of the Geneva talks in January 2014, thus giving the Assad regime the chance to regain its international legitimacy. Iran increased its military support to all of Hezbollah and over 13 sectarian militias that entered Syria with the objective of regaining strategic locations from the opposition.

The lack of action by the international community towards the unprecedented atrocities committed by the Syrian regime, along with the administrative and military instability in liberated areas created the atmosphere for cross-border terrorist groups to increase their mobilization levels and enter the scene as influential actors. ISIS began gaining momentum and took control over Raqqa and Deir Azzour, parts of Hasaka, and Iraq. On September 10, 2014, President Obama announced the formation of a broad international coalition to fight ISIS. Russia waited on the US-led coalition for one year before announcing its alliance to fight terrorism known as 4+1 (Russia, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Hezbollah) in September 2015. The Russian announcement came at the same time as ground troops and systematic air operations were being conducted by the Russian armed forces in Syria. In December 2015, Saudi Arabia announced the formation of an “Islamic Coalition” of 34 largely Muslim nations to fight terrorism, though not limited to ISIS.

These international coalitions to fight terrorism further emphasized the narrative of the Syrian uprising which was limited to countering terrorism regardless of the internal outlook of the agency yet again confirming the regime’s original claims. As a result, the Syrian regime became the de facto partner in the war against terrorism by its allies while supporters of the uprising showed a weak response. The international involvement at this stage focused on how to control the spread of ISIS and protect each actor from the spillover effects. The threat of terrorism coupled with the massive refugee influx into Europe and other parts of the world increased the threat levels in those states, especially after the attacks in the US, France, Turkey and others. Furthermore, the PYD-YPG present a unique case in which they receive military support from the United States and its regional allies, as well as coordinate and receive support from Russia and the regime, while at the same time posing a serious risk to Turkey’s national security. Another conflictual alliance is that of Baghdad; it is an ally of Iran, Russia and the Syrian regime; but it also coordinates with the United States army and intelligence agencies.

The allies of the Assad regime further consolidated their support of the regime and framing the conflict as one against terrorism, used the refugee issue as a tool to pressure neighboring countries who supported the uprising. On the other hand, the United States showed a lack of interest in the region while placing a veto on supporting revolutionary forces with what was needed to win the war or even defend themselves. The regional powers had a small margin between the two camps of providing support and increasing the leverage they have on the situation inside Syria in order to prevent themselves from being a target of such terrorism threats of the pro-Iran militias as well as ISIS.

In Summary, the international community has systematically failed to address the root causes of the conflict but instead concentrated its efforts on the conflict's aftermath. By doing so, not only has it failed to bring an end to the ongoing conflict in Syria, it has also succeeded in creating a propitious environment for the creation of multiple social and political clashes, hence aggravating the situation furthermore. The different approaches adopted by both the global and regional powers have miserably failed in re-establishing balance and order in the region. By insisting on assuming a conflictual stance rather than cooperating in assisting the vast majority of the Syrian people in the creation of a new balanced regional order, they have assisted the marginalized powers in creating a perpetual conflict zone for years to come.

Security Priorities

The security priorities of regional and international actors have been in a realignment process, and the aspirations of regional hegemony between Turkey, Arab Gulf states, Iran, Russia and the United States are at odds. This could be further detailed as follows:

• The United States: Washington’s actions are essentially a set of convictions and reactions that do not live up to its foreign policy frameworks. The “fighting terrorism” paradigm has further rooted the “results rather than causes” approach, by sidelining proactive initiatives and instead focusing on fighting ISIS with a tactical strategy rather than a comprehensive security strategy in the region.

• Russia: By prioritizing the fight against terror in the Levant, Moscow gained considerable leverage to elevate the Russian influence in the Arab region and an access to the Mediterranean after a series of strategic losses in the Arab region and Ukraine. Russia is also suffering from an exacerbating economic crisis. Through its Syria intervention, Russia achieved three key objectives:

1. Limit the aspirations and choices of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey in the new regional order.

2. Force the Iranians to redraft their policies based on mutual cooperation after its long control of the economic, military and political management of the Assad regime.

3. Encourage Assad’s allies to rally behind Russia to draft a regional plan under Moscow’s leadership and sphere of influence.

• Iran: Regionally, Iran intersects with Washington and Moscow’s prioritizing of fighting terrorism over dealing with other chronic political crises in the region. It is investing in fighting terrorism as a key approach to interference in the Levant. The nuclear deal with Iran emerged as an opportunity to assign Tehran as the “regional police”, serving its purpose of exclusively fighting ISIS. The direct Russian intervention in Syria resulted in Iran backing off from day-to-day management of the Syrian regime’s affairs. However, it still maintains a strong presence in most of the regional issues – allowing it to further its meddling in regional security.

• Turkey: Ankara is facing tough choices after the Russian intervention, especially with the absence of US political backing to any solid Turkish action in the Levant. It has to work towards a relative balance through small margins for action, until a game changer takes effect. Until then, Turkey’s options are limited to pursuing political and military support of the opposition, avoiding direct confrontation with Russia and increasing coordination with Saudi Arabia to create international alternatives to the Russian-Iranian endeavors in the Levant. Turkey’s options are further constrained by the rise of YPG/PKK forces as a real security risk that requires full attention.

• Saudi Arabia: The direct Russian intervention jeopardizes the GCC countries’ security while it enhances the Iranian influence in the region, giving it a free hand to meddle in the security of its Arab neighbors. With a lack of interest from Washington and the priority of fighting terror in the Levant, the GCC countries are only left with showing further aggression in the face of these security threats either alone or with various regional partnerships, despite US wishes. One example is the case in Yemen, where they supported the legitimate government. Most recently in Lebanon, it cut its financial aid and designated Hezbollah as a terrorist organization. Riyadh is still facing challenges of maintaining Gulf and Arab unity and preventing the plight of a long and exhausting war.

• Egypt: Sisi is expanding Egyptian outreach beyond the Gulf region, by coordinating with Russia which shares Cairo’s vision against popular uprisings in the Arab region. He also tries to revive the lost Egyptian influence in Africa, seeking economic opportunities needed by the deteriorating Egyptian economic infrastructure.

• Jordan: It aligns its priorities with the US and Russia in fighting terrorism, despite the priorities of its regional allies. Jordan suffices with maintaining security to its southern border and maintaining its interests through participating in the so-called “Military Operation Center - MOC”. It also participates and coordinates with the US-led coalition against terrorism.

• Israel: The Israeli strategy towards Syria is crucial to its security policy with indirect interventions to improve the scenarios that are most convenient for Israel. Israel exploits the fluidity and fragility of the Syrian scene to weaken Iran and Hezbollah and exhaust all regional and local actors in Syria. It works towards a sectarian or ethnic political environment that will produce a future system that is incapable of functioning and posing a threat to any of its neighbors.

During the recent Organization of Islamic Cooperation conference in Istanbul the Turkish leadership criticized Iran in a significant move away from the previous admiration of that country but did not go so far as cutting off ties. One has to recognize that political realignments are fluid and fast changing in the same manner that the “black box” of Syria has contradictions and fragile elements within it. The new Middle East signifies a transitional period that will witness new alignments formulated on the terrorism and refugee paradigms mentioned above. Turkey needs Iran’s help in preventing the formation of a Kurdish state in Syria, while Iran needs Turkey for access to trade routes to Europe. The rapprochement between Turkey and the United Arab Emirates as well as other Gulf States signifies a move by Turkey to diffuse and isolate polarization resulting from differences on Egypt and Libya and building a common ground to counter the security threats.

Opportunities and Policy Alternatives

The political track outlined in UNSC 2254 has been in place and moving on a timeline set by the agreements of the ISSG group. The political negotiations aim to resolve the conflict from very limited angles that focus on counter terrorism, a permanent cease-fire, and the maintenance of the status quo in terms of power sharing among the different groups. This political track does not resolve the deeper problems that have caused instability and the regional security threat spillover. This track does not fulfill the security objectives sought by Syrian actors as well as regional countries.

Given the evolving set of regional alignments that has struck the region, it is important to assess alternative and parallel policies to remain an active and effective actor. It is essential to look at domestic stabilizing mechanisms and spheres of influence within Syria that minimize the security and terrorism risks and restore state functions in regions outside of government control. Local Administration Councils (LAC) are bodies that base their legitimacy on the processes of election and consensus building in most regions in Syria. This legitimacy requires further action by countries to increase their balance of power in the face of the threat of terrorism and outflow of refugees.

A major priority now for regional power is to re-establish order and stability on the local level in terms of developing a new legitimacy based on the consensus of the people and on its ability to provide basic services to the local population. The current political track outlined by the UNSC 2254 and the US/Russian fragile agreements can at best freeze the conflict and consolidate spheres of influence that could lead to Syria’s partition as a reality on the ground. The best scenario for regional actors at this point in addition to supporting the political track would be to support and empower local transitional mechanisms that can re-establish peace and stability locally. This can be achieved by supporting and empowering both local administration councils and civil society organizations that have a more flexible work environment to become a soft power for establishing civil peace. Any meaningful stabilization project should begin with the transitioning out of the Assad regime with a clear agreed timetable.

Over 950 Local Councils in Syria were established during 2012-2013, and the overwhelming majority were the result of local electing of governing bodies or the consensus of the majority of residents. According to a field study conducted by Local Administration Councils Unit and Omran Center for Strategic Studies, at least 405 local councils operate in areas under the control of the opposition including 54 city-size councils with a high performance index. These Councils perform many state functions on the local level such as maintaining public infrastructure, local police, civil defense, health and education facilities, and coordinating among local actors including armed groups. On the other hand, Local Councils are faced with many financial and administrative burdens and shortcomings, but have progressed and learned extensively from their mistakes. The coordination levels among local councils have increased lately and the experience of many has matured and played important political roles on the local level.

Regional powers need domestic partners in Syria that operate within the framework of a state institution not as a political organization or an armed group. Local Councils perform essential functions of a state and should be empowered to do that financially but more importantly politically by recognizing their legitimacy and ability to govern and fill the power vacuum. The need to re-establish order and peace through Local Councils is a top priority that will allow any negotiation process the domestic elements of success while achieving strategic security objectives for neighboring countries.

Published In The Insight Turkey, Spring 2016, Vol. 18, No. 2

TRT World - Interview with Dr. Sinan Hatahet on a Political Solution in Syria

Dr. Sinan Hatahet Talks About the Sieges in Syria and the Opposition in Geneva

TRT World - Interview with Dr. Ammar Kahf on Russian Airstrikes in Syria

Dr. Ammar Kahf from Omran for Strategic Studies discusses Russia's Airstrikes on Hospitals and Civilians in Syria

On the US-Russian Agreement on Cessation of Hostilities in Syria

Abstract: The statement on the cessation of hostilities in Syria released on February 22, 2016 following meetings between Kerry and Lavrov indicate the continuance of a joint US-Russian policy to push for a political process that excludes all “rebel” parties. This proposition reinforces new rules to push forward a political transition in Syria devoid of any political or legal guarantees that would end an era of state terrorism. The statement further entrenches the Russians in the Syrian file by graduating them from an ally of the regime to an internationally sanctioned sponsor of the political process and ultimately an overseer of the ceasefire with rights to strike “other groups” not specified in the agreement

Overview of the Statement

• Enhancing the position of Russian leadership in setting the conditions for a final settlement in Syria: the statement issued by the ISSG Ceasefire Task Force, established by the Munich Communique in February 11, 2016, led by the US and Russia, indicates the complete delegation of executable details of the final settlement from Washington to Moscow. Kerry has been committed to the Russian vision which has been repeatedly revealed in Lavrov’s public statements since the Vienna meetings last year. In turn, Russia is given a free hand to target any opponent to its proposal under the pretext of the fight against terrorism while at the same time ensuring the safety and security of all other groups not designated as terrorist organizations. This premise is evident in the exclusion of all groups who do not express commitment to the cessation of hostilities in addition to excluding ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra and any other group designated by the UN Security Council as terrorist groups in Syria.

• Presenting the Syrian regime military as the only legitimate force of the Syrian state: the statement reiterated the legitimacy of the Syrian regime forces and militias as “the Armed Forces of the Syrian Arab Republic”. It further grants the Syrian Armed Forces exclusive rights to fight terrorism and Syrian opposition revolutionary forces. According to the statement, the regime forces become the guarantors of establishing peace and security in Syria. Meanwhile, all other Syrian forces; including the national moderate opposition, the Syrian democratic forces and the YPG units, are not allowed to fight ISIS or other groups designated as terrorists without authorization from the Syrian regime. Furthermore, the Syrian regime, with international support, is thus allowed classify the national moderate opposition forces as opponents of the regime’s state in the case they reject the cessation of hostilities, and therefore target and attack these forces without any legal or political deterrents.

• Managing exceptions within the agreement and maintaining the fluidity of the military situation: As a whole, the exceptions in this statement and previous UN resolutions maintain the fluidity of the military situation in Syria to the advantage of the regime and its allies. The agreement also excludes from the political process in Syria all of ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra and other groups to be identified later on by the UN Security Council. The statement considers the national forces that reject the agreement as legitimate targets for the international coalition, Russia and regime forces. In contrast, the statement does not exclude from ceasefire arrangements any of the Iran-supported foreign militia. Instead, it considers them as legitimate groups because they fight along the “Syrian Armed Forces”. The national opposition forces are thus forced to stop all of their military actions against regime forces and its allies without exception and no matter the circumstance.

• Seperating ceasefire from negotiations, thereby abolishing the Political Solution: UN Security Council Resolution No. 2254 closely links a nationwide ceasefire with taking real steps towards a transitional process. The draft statement, however, does not maintain any such links and overlooks any of the preconditions to engage in tangible political progress. The statement concludes with a demand that all parties commit to the release of detainees without deeming it a prerequisite for engaging in the political process or a ceasefire. Furthermore, urging all parties to allow easy access for humanitarian assistance is basically the same as the implementation of Security Council Resolutions No. 2139 and 2165 – something the international community has failed to hold the regime accountable for since the passing of these resolutions. Moreover, efforts to force the regime to follow the timetable set out by UN Resolution 2254 are meaningless once the national opposition forces are stripped from their ability to arm themselves and fight the regime and allied forces per the proposed cessation of hostilities agreement.

Procedural Problems within the Text of the Agreement

The statement solidifies the status-quo on the ground prior to the commencement of negotiations, and eliminates any room for objections. Thus, given the reality on the ground, the only way to interpret what the statement means by “preparing the conditions for the peace process” is the surrender of the opposition. The statement includes several problems that will result in its failure and they are as follows:

1. The US and Russia are responsible for defining the non-target areas. Such an arrangements is feasible in the south due the availability of the right conditions, however, the same arrangement is impossible in the Idlib province where the areas held by Jabhat al-Nusra and the national resistance forces are geographically intertwined.

2. There is ambiguity surrounding the final wording which describes the monitoring mechanisms. As it appears, the text maintains the legitimacy of the Russian expansion in northern Syria. It also allows the regime forces and its allies to target the national resistance forces, under the pretext of fighting terrorism, even while conducting investigations into questionable attacks.

3. Accountability mechanisms for breaching the agreement are limited to excluding those who violate the ceasefire from international protection ensured by the statement. This is not achievable except by US-Russian approval – thus granting the regime immunity to pursue its military operations under Russian sponsorship.

4. The statement institutionalizes security and intelligence cooperation and information exchange between the US and Russia but offers no guarantees against the misuse of intelligence of avoiding targeting the headquarters and facilities of national resistance forces. Moreover, it does not compel the implementing parties to disclose their internationally-agreed military objectives.

A Fragile Agreement Jeopardizing Regional Peace and Security

Similar to previous agreements, the US-Russian agreement fails to handle the underlying causes of the ongoing conflict in Syria, namely, the continuation of Bashar Alassad as the head of state and the persistence of systematic violence and terrorist acts against unarmed civilians carried out under the pretext of fighting terrorism with the blessing, support and participation of Russia. The failure of the international community to stop the bloodshed of the Syrian people and the destruction of state institutions led to the fragmentation of the Syrian society. This created a political and institutional vacuum, which was taken advantage of by extremist groups and grew within it. Another result was the development of a stifling humanitarian disaser that led to the largest refugee cisis since WWII.

Regionally, Iran exploited the crumbling regime to control state institutions end secure its presence in the Levant after tightening its grip on Baghdad and Beirut. In turn, Iran improved its political standing and managed to sign a historical nuclear deal with the US. The nuclear deal’s impact is further manifested through the deepening partnership between Tehran and Washington in managing the regional issues militarily and Iran’s increased aggressive interactions with Gulf countries, especially Saudi Arabia. The current US-Russian agreement further enhances the Iranian stance and legitimizes the operations of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard in Syria while also maintaining geographical connections with the Iranian backed militias in Iraq and Hezbollah in Lebanon. Hence, Iran has institutionalized a continuous military presence commensurate with its political influence in the region for the first time since the Islamic revolution in 1979.

As it relates to Turkey, the Syrian dilemma affected the domestic situation in two ways: First, at the humanitarian level, with the nonstop flood of refugees – posing economic and security strains on Turkish state institutions and negatively affecting relations between Ankara and the EU. Secondly, at the security level, the vacuum created by the collapse of the Syrian state resulted in the rise of both ISIS and the separatist Kurdish movements in the north, threatening the Turkish inland. Within a span of four months, Ankara suffered two terrorist explosions by both groups. Istanbul and the border city of Suruc and areas in southeast Turkey suffered similar operations resulting in the deterioration of the security situation and reviving PKK dreams to separate. The current US-Russian agreement on Syria ensures the continuity of the security threats to Turkey as it fails to resolve the crisis of refugees fleeing through Turkey to Europe. It also maintains the status quo along Turkey’s southern border allowing for extremism to continue spreading. Furthermore, the US-Russian deal creates easily accessible equipment and supply routes for the PKK fighters in the border areas with Syria, especially in southeast Turkey where the PKK is most active.

Scenarios for the National Resistance Forces

The proposed formula for the cessation of hostilities in Syria maintains the fluidity of the crisis, both politically and militarily, as established by the Geneva Communiqué. Such uncertainty was exploited by Russia, Iran and the Syrian regime to reset the rules of the game toward their joint interests, end the Syrian national resistance and exploit regional security to enhance their goals. As the international community fails to face the Russian and Iranian aggressive agendas, it is imperative that the political and military opposition to work toward ending the liquidity of the situation in Syria.

The Higher Negotiations Council (HNC) was successful in pursuing a policy of conditional acceptance for the demands laid out by the ISSG in order to look for new ways out of the dilemma imposed on the opposition due to the US’ significant pressure in causing the decrease of financial and logistical support. The HNC also succeeded in maintaining its unity despite many internal elements leaning towards reconciling with the regime. Also, the HNC was able to continue to politically perform and maneuver despite Russia playing one of its last cards in an attempt to eliminate any remaining chance for the Syrian people to achieve a just and sustainable political solution.

Therefore, in order to for the national political opposition to recapture its independent decision making it should:

1. Fully reject the statement and threaten to withdraw from negotiations since all ceasefire conditions in the proposed text entail excluding groups and organizations in geographical locations intertwined with opposition strongholds. The Russians and Americans must offer guarantees to not use such exclusions as pretexts to target the opposition.

2. Insist that the ceasefire takes into consideration all of the opposition’s concerns and make a condition, guaranteed by the ISSG, that a transition without Assad will start immediately. This should be clearly stated in the expected Security Council resolution for this agreement.

3. Work towards more decisive support by the allies of the opposition, both politically and militarily, and the designation of foreign militias supporting the regime as terrorist organizations. In addition to the establishment of a joint crisis chamber that includes the HNC and the national resistance forces.