The Syrian Badia: A Map of Influence, Control, and Ambiguous Operations

Following its “defeat” in 2019, the Islamic State (ISIS) adapted in response to both the new scope of its capabilities and the intensified determination of its adversaries. by transitioning from consolidation of power and territorial dominance under a centralized leadership, to a decentralized strategy, relying on autonomous cells and rapid, agile operations. These operations vary in their intensity, patterns, and frequency, depending on the geographic regions and the nature of the forces in control. Operations for which ISIS officially claimed responsibility coincided with other ambiguous operations carried out under its name without an official claim of responsibility. The latter operations targeted both civilian and military individuals and groups through kidnappings and killings.

Although various areas of control have witnessed this type of ambiguous operations, the Syrian desert represented the main stage for it. The period between the 2019 and 2024 saw an increase in operations targeting civilian groups from Arab tribes, especially in the southern desert of Aleppo, which is connected to the desert of Hama, the desert of Homs, as well as the deserts of Al-Rusafa in Al-Raqqa, and Deir Ezzor. Some of these attacks resulted in mass killings that claimed the lives of hundreds of members of tribes in the region, such as Bani Khalid, Al-Amoor, Al-Dulaim, Al-Boshaban, Al-Hadedeen, Al-Gomlan, and Al-Uqaydat tribes. Furthermore, sporadic attacks targeted individuals and groups of shepherds and their livestock, and truffle hunters, rendering the truffle season in the desert deadly.

Several factors contributed to the ambiguity surrounding these operations, notably: the presence of various controlling forces and militias with divergent interests, including ISIS cells that utilized parts of the desert as sanctuaries for launching rapid assaults. The majority of these mass killings transpired on the main highway networks, which is either controlled by Iranian backed militias or is located within areas of their strategic interest, especially in proximity to various energy resources (such as oil, gas, and phosphate) within the region. Moreover, ISIS did not claim responsibility for most of these operations, and their nature differed from what those that ISIS has previously claimed. in terms of tactics and the nature of the targets. Notably, local tribes have accused other forces of being involved in these attacks, particularly the Iranian-backed militias in the region.

The following map highlights the main areas of control in the Syrian desert, as well as key transportation routes, vital energy fields, and areas that have seen ISIS cell activity, and attacks, massacres, and ambiguous operations carried out in ISIS' name between 2019 and 2024.

and to view the map in high resolution: https://bit.ly/44fzTuI

Access the full study (in Arabic) via the Omran Center here: https://bit.ly/3VmhdXC.

Workshop | The Security structures in the liberated areas

On November 28, 2019, in Gaziantep, the Stabilization Committee in partnership with KALmec (Kalyoncu Middle East Research Center) has held a workshop entitled ‘’the Security structure in the liberated areas’’.

In the second section the Executive Director of Omran for Strategic Studies Dr. Ammar Kahf, talked about the security structure in the region. He asserted that the figures given in the presentation prepared by the Stabilization Committee are correct; he said we are sure because we have been working for two years now to collect information on bombings and terrorist attacks taking place in the region. He also said we should work to regulate relationship and strengthen coordination between the military, police and civilians through focused sessions on reference, governance, transparency, organization and administrative control.

The Workshop attended by the Syrian Interim Government’s Minister of Justice and the representative of Syrian Interim Government’s Interior Ministry, alongside Heads of Local Councils, representatives of civil & military police forces, representatives of Military factions, lawyers, Judges and CSO representatives in the northern countryside of Aleppo. As they are directly concerned with the security issues in the liberated areas in North of Syria.

What’s Next for the Opposition After Aleppo

Abstract: The fall of Aleppo is not the end of the opposition in Syria, but perhaps marks the beginning of a Russian attempt to consolidate spheres of influence that are controlled by its regional allies and then push for a political track within its interpretation of political transition. What all actors understand is that it is no longer an option to return to the conditions prior to 2011. The Syrian opposition and its allies still have important cards to play including the empowerment of Local Administration Councils that gain legitimacy from the electorate and able to conduct stabilization programs that are essential during the transition. The opposition still control key strategic locations that should be empowered or a managed cease fire should be implemented to stop the misbalancing of powers.

The Syrian uprising has witnessed several phases each with different features and challenges. They ranged from the non-violent resistance phase, to the militarization, to the spread of cross-border ideological radical groups, to the internationalization of the conflict, the Russian intervention, and finally the consolidation of spheres of influence and control. Political negotiations can be characterized to have gone through phases beginning with the Geneva Communique in 2012, which calls for the formation of a transitional governing body with full executive powers, then the Geneva I, II, and II talks took place starting January 2014 until 2016 where negotiation rounds were stalled every time because of the insistence of the Assad regime to frame the talks for fighting terrorism and not the formation of a transitional governing body with full executive powers. Towards the end of 2015 and throughout 2016, there were a series of meetings called for by Russia and the United States in Vienna and other European capitals where a new international group was formed called the International Syria Support Group (ISSG) that called for a cessation of hostilities as a first step to re-start political negotiations with four main tracks: Humanitarian, Security, Refugee Resettlement, and civil society. A joint commission was formed by Russia and the US to oversee the cessation of hostilities process and the cease-fire agreements. During this process the United Nations Security Council approved the Russia-US agreement in the ISSG and issued UNSC Resolution 2254 calling for political negotiations with a strict timeline, where a cease fire takes place and ISIS and Jabhat Nusra will be targeted, political negotiations to reach a transitional body that ratifies a new constitution and holds elections to inaugurate a political transition. So far the UNSC 2254 has not been on schedule and that brings us to the last phase where Russia, Iran and Turkey met in

December 2016 and issued the Moscow Declaration. The agreement comes after the fall of Aleppo and puts out a more serious attempt to push a political transition process.

This expert brief argues that the fall of Aleppo was a result of a systematic policy by Russia to consolidate territories under the regime control, the Euphrates Shield zone, the Southern Front, the Kurdish controlled zones, then propose a political track according to its interpretation of “political transition”. In the face of the Russian policy, there was no other well-planned policy, underpinned by necessary means, implemented by other local, regional or international powers. The role of Iran is limited within the scope of the Russian policy, yet remains critical and strong on the ground, especially in its control of transportation routes to Lebanon. Additionally, the Russian diplomacy is far more aggressive and consistent with a clear determination for a political track without a regime change paradigm.

For Syrian opposition groups, the fall of Aleppo also puts forward a set of critical challenges and offers fewer options for diplomatic maneuvering while maintaining the balance of power through a freezing of hostilities or a nationwide cease-fire that freezes spheres of influence and control thus creating ground for negotiations. The Syrian opposition should adapt to the new conditions by generating new tools and mechanisms to deal with the new phase. Supporters of the Syrian opposition should also create conditions where Syrian “agency” and local actors are involved in the peace-making and stabilization process from the bottom-up.

The fall of Aleppo was a coordinated effort allegedly aiming at creating new conditions for a political track to be approached according to the Russian terms. This effort can be characterized by the following features:

1. A consistent marginalization of societal demands and aspirations while prioritizing a security based approach at any price, including forced evacuations of residents in Aleppo as well as Daraya, Zabadani and other regions. Local agency is often ignored and assumed to be a “proxy” to outside forces. This is why Russia has attempted to create a “Moscow 1 Syrian opposition”([1]) and “Homaimim opposition”([2]) to legitimize a “political track”; while realizing these groups’ inability to represent relevant Syrian actors in control of territories and borders.

2. The priority of the regime and its allies was to re-gain control of Aleppo at any price while postponing efforts to fight ISIS in order to freeze zones of influence and presumably reach a political agreement that would then focus on fighting ISIS and Jabhat Fath al-Sham. This explains the minimal reaction by the regime and Russia to ISIS re-capturing Palmyra.

3. The “Grozny” approach([3]) during the latest military operation to regain Aleppo after over two years of failed attempts by the Assad regime ends a phase that was featured by the maintenance of the balance of power approach in the management of the conflict. While it was clear the opposition failed to present governance solutions to address security threats, the current scenario puts excessive political and military pressure on the opposition to offer concessions and agree to a Russian framed political track. This will lead to further radicalization and for increased recruitment by terrorist groups who manipulate a victimized narrative.

Additionally, this will lead to further chaos and fragmentation of opposition held areas making it incapable of implementing any transitional programs.

Opposition’s options

The opposition choices are very limited. They need to be empowered to exercise self-criticism and review its positions and strategies of addressing the political track, including not falling in haphazard mergers between armed groups without a clear agreement on roles and responsibilities as well as relationships with local societal actors. It is of strategic importance now more than ever to empower Local Administration Council that are the only representative bodies in Syria today, as they are structured from the bottom up([4]). Field research shows a high positive correlation between citizen involvement and participation in local councils and the ousting of terrorist groups([5]). Moreover, Local Councils are service providers with clear political roles in representing citizens’ views and limit the control and influence of armed groups. Stabilization programs should rely on local councils and civil society organization more than on armed groups.

The recapture of Aleppo by militias allied with Bashar Assad was not possible without the air support of the Russian Air Force. The forces allied with the regime are very fragmented and disorganized that they could not alone recapture the city of Aleppo([6]). There were several attempts during the past 12 months to recapture the city but none was successful precisely because the Russians had different calculations and did not trust the ability of ground troops to take full control. The amount of military warfare waged on Aleppo was unprecedented and excessive, thus indicating a difficult front they were unable to previously capture without its full destruction and evacuation of all its citizens. The Assad regime remains very fragmented and does not have a monopoly to the “use of force” anymore thus suffering from diminished legitimacy. Information from the ground indicate that the Aleppo operation was fully managed by Russian and Iranian officers, while marginalizing Syrian-regime militias from decision making circles([7]).

Assad in fact has regained a city of rubble devoid of its native population. This poses important questions regarding the upcoming negotiations processes and the place of the evacuated residents in it. Great uncertainty covers the refugees return before the start of any political process, hence affecting the legitimacy of the process. Indeed, Aleppo was strategically very important to the opposition, but it is not the end of the struggle. The opposition is still in control of most borders, major transportation routes, the Southern Front, Euphrates Shield zone, and Idlib. Numbers of armed forces in opposition areas are not to be taken lightly.

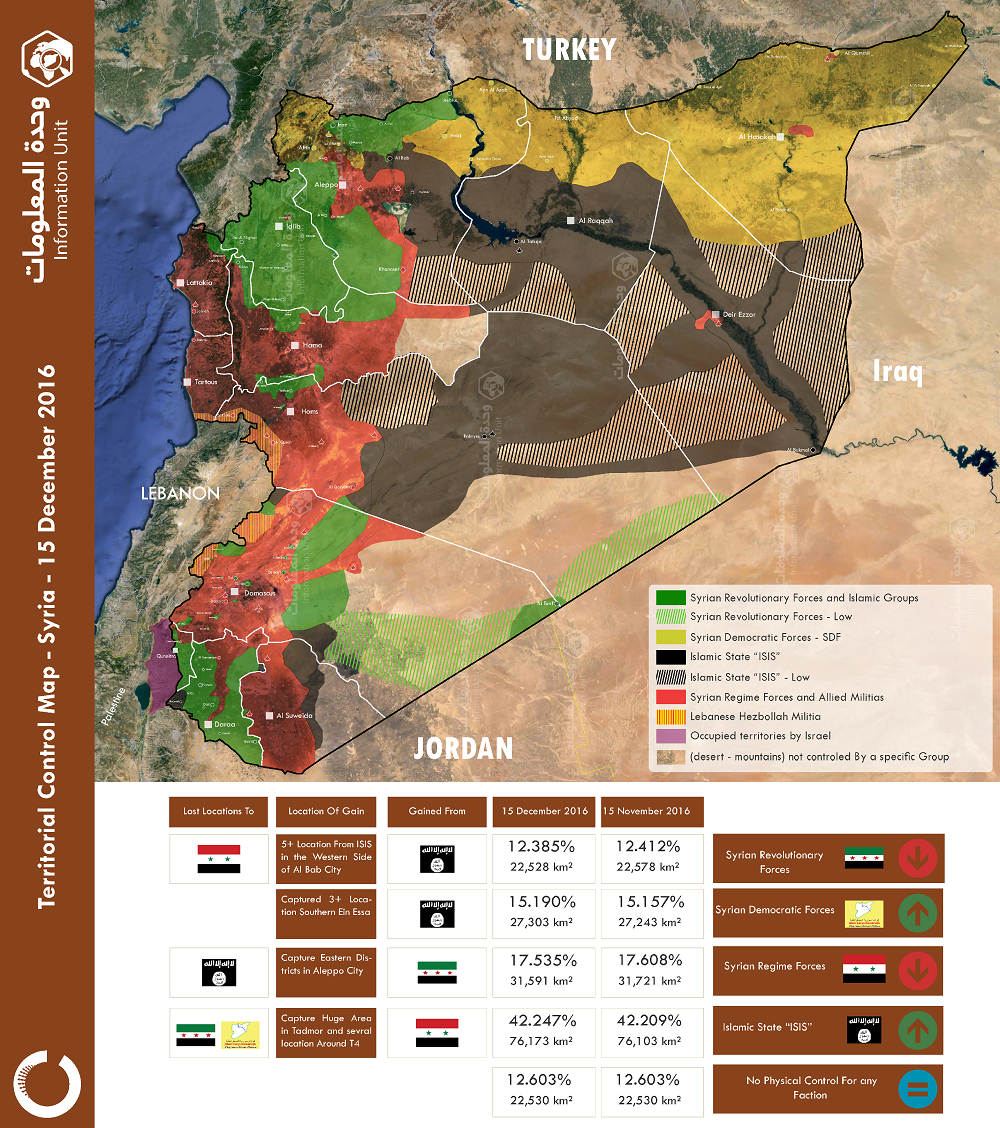

Territorial Control Map - Syria - 15 DEC 2016, No (1)

Another element to be considered is the new evolving Turkish role that focused on securing its borders and national security through the Euphrates Shield operations that are now close to Al-Bab. These forces draw the limits of Turkish military options to the objective of fighting ISIS and ending any possibility of PYD connecting the area between its Kobane and Afrin cantons, hence creating a territorially contiguous Kurdish enclave along Turkey’s borders. While Aleppo has historic, political and economic significance to Turkey, the Turkish role shifted to become a mediator to help create a ceasefire agreement and support on humanitarian efforts. Perhaps the best scenario is a controlled and consolidated territory in the north of Syria where no foreign fighters or other radical Islamist fighters can operate. This serves the objective of stabilizing the conflict and providing new options for a political settlement. This also requires an empowerment of local councils in these zones that provide local services and empowering civilians against militants which seeds for democratic values and institutions.

The Moscow Declaration and the Challenges Ahead

The Moscow Declaration established a new set of expectations by actors who are present on the ground as compared to previous attempts by a larger setting such as in Vienna and Geneva. The Declaration also increases the importance of creating a platform for Syrian opposition groups to avoid previous mistakes and consolidate their bodies and decision-making processes. The new phase requires different diplomatic and military tools and mechanisms; and the current Syrian opposition structures and negotiation strategies fall short of meeting the challenges of the current phase.

The moment also requires a plan to deal with Jabhat Fath al-Sham (previously known as Nusra Front). Syrian groups should end all communications and coordination with this group, and work to push them out of inhabited areas of Idlib. This could be done by highlighting the role of representative local councils as the civilians “horses for peace”, while pushing the militias to be regulated under the new civilian administration in order to deliver security. Holding elections as means to re-establish localized governance is a stepping-stone to stabilization programs. This also requires the limiting of armed groups interferences in public life and the provision of public services. The model presented by the Euphrates Shield in re-organizing Free Syrian Army groups, professionalizing them, and limiting their mandate to fighting terrorism can be adopted at least temporally. These programs should not wait a political track. It should serve the purpose of consolidating opposition areas, countering terrorism, and re-establishing order and rule of law. This will empower the opposition to be better equipped as a “state” not as “opposition” to enter negotiations as a reliable partner. Many claim this is unrealistic, but I claim that a political will and a paradigm shift by opposition groups, local councils, and armed groups can make this a reality.

For a sustainable peace plan to be maintained, all relevant actors on the ground should be involved and not treated as a “proxy” with countries “guaranteeing” positions on their behalf. Assuming that a resolution could be reached by forming a government with members from different “sides” of the conflict overlooks the true societal nature of the uprising and assumes that citizens can go back to the former rules of governance and the former forged social contract. A new social pact based on decentralization of governance and administration should be agreed upon by Syrians. This means all foreign fighters beginning with the 41 militias([8]) supported by Iran including Hezbollah and their re-located foreign families should leave Syria. This requires a systematic process and a full plan that does not only rely on hard power and use of force. Syrian actors should be empowered to take responsibility of their local cities and towns and not allow them to operate freely. Additionally, the fight against ISIS and al-Qaeda affiliates cannot be won without a unified Syria, an end of the current system of governance, a new military-security philosophy, and the exit of Shia militias that reinforce the ISIS narrative and increase its recruitment world-wide. The presence of these terrorist militias is the main reason for the imbalance of power in Syria that lead among other reasons to the spread of ISIS.

It is not over yet. The opposition still hold several important cards that should be wisely maintained for the best of all parties. There still remains strongholds for the Syrian opposition that require careful negotiations to ensure that it is not lost and does not undergo a similar fate to that of Aleppo, by including them in a nation-wide ceasefire and implementing an agreement for a weapon-free zone with Russian guarantees. These areas including the Eastern Ghouta in Damascus Suburbs, and Idlib as a center for refugee resettlement and economic reconstruction. The liberation of Raqqa will also determine the trajectory of the conflict and the nascent control zones, refugee outflow policies and programs, and counter-terrorism programs. All the forgone are potential cooperation issues between the foreign stakeholders and the Syrian opposition in order to reverse the vicious cycle of conflict.

The conflict in Syria will not end with fall of Aleppo and the new round of political talks unless relevant actors “local agency” is involved and have a buy-in to the transition plan. Local actors include Local Councils and influential figures and civil society groups. The political process cannot proceed without applying the same rule to all sides of the conflict; the exit of all foreign fighters. The weakest element in the equation is the Asad regime that has been deeply fragmented with multiple militias and loyalties within its composition thus making it incapable of fulfilling any agreement they sign on to, without guarantees by Russia and Iran. A true transition plan should address the demands of the local citizens and establish a new beginning for the reconstruction of Syria.

Published In ALSharq Forum, 29/12/ 2016: https://goo.gl/ecsOjf

([1]) The Russian Foreign Ministry hosted Moscow 1 and 2 meetings and invited opposition figures such as former government official Kadri Jamil, with the purpose of creating a legitimate body to take part in political negotiations but with demands limited to democratic changes in government to include more people rather than demands held by protestors. This group can be characterized as a group of individuals with little ties to relevant actors on the ground. This group alone cannot implement a peace truce but were brought to dilute the positions of the “opposition” and show a Russia-aligned group that could be a partner in the future.

([2]) Homaimim Russian base in Syria has been a hub hosted by the Russian Defense Department to bring together Syrian “opposition” that live in regime held areas and create “shell” bodies that represent their limited demand for inclusion and diversity while being more aligned with the Russian narrative of the conflict. These members represent primarily interest groups that are linked with the regime and not any actor that has the power to implement or “sell” an agreement with relevant actors on the ground.

([3]) In 1994-1995, Russian forces invaded the city of Grozny to stop the armed uprising and use lethal force and all destructive tools. Many refer to Grozny as it seemed a policy being implemented in the recapture of Aleppo where the eastern city was fully destroyed without any distinction of those being attacked and using all type of weaponry.

([4]) In the survey conducted by the Local Administration Council’s Unit (LACU) and Omran for Strategic Studies in Summer of 2015, 405 local councils were interviewed and asked about their governance structures. This number reflects those councils we were able to reach, but represents 90% of local councils in operation. About one-third of these interviewed say councils’ members are voted by local constituency and two-thirds by local consensus of local actors and civil society. These Councils are tasked with provision of basic services to local residents, including local governance, permits for NGO’s operation, public infrastructures, local safety, rescue services (White Helmets was started by Local Councils), education, and health services.

([5]) An example could be seen in the Southern Front where there are 76 local councils on the city and village level and the agreement between local councils and armed opposition groups allowed for Nosra to have little if any existence in areas governed by local councils. Another similar example is perhaps, Daraya (Damascus Suburb), and Maarat Noman (Idlib).

([6]) Omran for Strategic Studies Information Unit researchers in Aleppo reported large number of fighters pouring into the military fronts from al-Nujaba Shiaa Militia, and that the ground control command was with Iranian militias with minimal official Syrian Army presence. Also see: http://edition.cnn.com/2016/12/12/middleeast/syria-analysis-tim-lister/

([7]) Personal interview (Mohamad from Homs originally, does not wish to be named) with defected soldier who was stationed in Al-Qusair after its fall, then stationed in Deir Azzour before defecting, interview date August 25, 2016. He revealed that in military operation rooms where Hezbollah officers preceded, they did not allow Alawite Syrian officers to stay in the room during operational planning, and also forced them to taste food cooked before Hezbolla officers eat.

([8]) Omran for Strategic Studies Information Unit map of foreign militias allied with the regime including numbers and training locations, unpublished, dated Nov 25, 2016.

TRT World Interview with Ammar Kahf about on the latest in Aleppo

Dr. Ammar Kahf Talks about on the latest in Aleppo