Introduction

Following the fall of the Assad regime, a critical opportunity has emerged to conduct thorough and methodical security vetting operations targeting all commercial enterprises. These operations, grounded in official documentation issued by state ministries, aim to uncover companies linked to former regime officers and other human rights violators—whether registered in their own names or under those of family members. The process includes tracing the assets and financial flows of these entities, followed by the freezing of their holdings as a necessary interim measure. This would allow for a comprehensive legal review and the adoption of appropriate decisions regarding their status, ultimately ensuring the protection of national resources and their redirection toward serving the public interest ([1]).

The Assad regime’s security apparatus long sought to maintain strict secrecy around itself. However, this veil of secrecy began to erode following the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, as defections and leaks exposed a significant documents and information. These disclosures made it possible to trace both the formal and informal networks of the regime and to better understand the nature of relationships among its officers—within state institutions and beyond.

Before the regime's collapse, a substantial body of verified data had already been collected—particularly concerning officers under international sanctions([2]). The findings revealed that many of these individuals owned companies operating across various sectors, either directly or through relatives. This stands in clear violation of the previous Military Service Law, which explicitly prohibited voluntary military personnel from engaging in commercial activities, whether directly or by proxy. These findings suggest that some of these companies may have been established under official direction, as part of a systematic exploitation of power for personal gain or to serve the interests of the regime itself ([3]).

This paper seeks to establish a framework for addressing commercial activities linked to officers of the Assad regime and their family members. It does so by analyzing the motivations behind the creation of these enterprises and the objectives they were intended to serve. In addition, the paper outlines proposed future measures—including asset freezes and the redirection of resources toward national development. It also includes case documentation of several companies involving relatives of officers implicated in human rights violations.

Notably, the establishment of these companies was not merely a response to temporary economic hardship. Rather, it was driven by a combination of factors aimed at securing personal financial interests for regime officers and generating alternative revenue streams to sustain the regime amid declining official resources and mounting sanctions pressure. These companies also formed part of a broader strategy to ensure the continuity of power—by circumventing sanctions and reinforcing the regime’s intertwined networks of economic and security influence.

The Economic and Strategic Objectives Behind Establishing These Companies

The companies linked to regime officers were not merely conventional economic ventures. Rather, they served multiple functions—generating profit, providing protection, and advancing the regime’s security interests. This is evident in a set of underlying objectives :

Money Laundering

The scale of violations and crimes committed by the Assad regime—through its officers and security personnel—is no longer in question. These abuses extended far beyond systematic killing and torture to include widespread financial extortion and the imposition of informal levies, including the blackmail of detainees’ families. Such practices became a primary source of income for regime officer([4]).

These commercial enterprises played a significant role in laundering money under a legal veneer on behalf of regime officers. The funds laundered through these companies stemmed from a range of illicit sources—including extortion, bribery, administrative and financial corruption, and the systematic looting of abandoned cities, commonly referred to as “area custodianship” following the forced displacement of residents. This also included proceeds from smuggling operations conducted both within and beyond Syria’s borders, as well as from the drug trade—particularly captagon—which has become one of the regime’s most prominent sources of illicit financing.

Monopoly and the Elimination of Competitors

These companies contributed to consolidating monopolistic control over state-linked contracts and tenders, with security influence playing a pivotal role in awarding such deals to businesses owned by regime officers or their commercial fronts. Competing firms were systematically excluded, enabling these companies to reap enormous profits at the expense of public resources—under a legal framework that appeared procedurally sound.

The pervasive lack of financial transparency—both within these companies and across state institutions—further obstructed access to reliable data on executed contracts, significantly limiting efforts to trace transactions or hold those involved accountable.

Security Dimensions of Concealment

The establishment of some of these companies served clear security objectives—namely, concealment and operating on behalf of the regime. Certain contracts with state institutions, particularly those involving security agencies, required the involvement of front companies that maintained a high degree of apparent credibility. This structure enabled the concealment of direct ties between these entities and security institutions, allowing them to evade sanctions by exploiting the lack of detailed knowledge about such affiliations in several countries.

For instance (see appendix), “Sahar Mahmoud” and “Aya Hassan” established a company named ShamCoders, which specializes in software development and technology imports([5]). In reality, the company is owned by the wife and daughter of Major General Kamal Hassan, the long-standing head of Military Intelligence, who has been under U.S. sanctions for years. Those behind the company leveraged this structure to bypass international monitoring and continue their commercial activities out of public view.

Expansion into International Institutions and Circumvention of Sanctions

The activities of regime-affiliated companies were not limited to the domestic market. Many expanded their reach to penetrate international institutions and circumvent sanctions regimes through commercial fronts and complex economic networks that are difficult to trace. These companies engaged in the following practices:

Contracting with International Organizations

A significant number of these companies benefited from United Nations procurement contracts. Several UN agencies purchased supplies or paid for services provided by these firms, despite being aware of their connections to regime security officers. Over the years([6]), these officers exerted subtle pressure on UN agencies and personnel—ranging from implicit threats to direct intimidation, as well as exploiting corruption among certain staff members or leveraging personal relationships with officers.

One notable example is the daughter of Major General Hussam Louka, then-head of the General Intelligence under the Assad regime. She was employed by the UN in Syria([7]), reflecting a broader pattern of security influence embedded within international institutions.

Furthermore, according to UN procurement databases, the organization contracted with companies linked to high-ranking officers from Syria’s security services (see appendix). These include Al Daraja Al Oula (First Class), a company owned by Nazhat Mamlouk, the youngest son of Major General Ali Mamlouk—former head of the National Security Bureau and top security advisor to Bashar al-Assad. Contracts also involved companies owned by the son of Brigadier General Khalil Zgheibi, an officer in the Military Intelligence Directorate.

What is particularly alarming is that the United Nations does not consistently disclose the names of all companies it contracts with in Syria. Some are listed under the generic classification of “unknown vendors.” Statistics indicate that this category accounts for approximately 18.5% of total procurement activities([8]), representing a serious transparency gap and heightening the risk that some of these companies may be linked to suppliers implicated in human rights violations.

Exploiting Reconstruction Projects and Evading Sanctions

Evasion of Western sanctions was a primary driver behind the establishment of these companies. Regime officers often created businesses under the names of relatives or close associates, using them as commercial fronts that made legal accountability significantly more difficult. This tactic complicated the efforts of both the new Syrian administration and international actors seeking to enforce sanctions, as tracking structural changes within these companies or proving their links to sanctioned officers or their family members became increasingly challenging.

Illicit enrichment operations extend beyond companies officially registered in the names of officers or their relatives. They also include expansive networks of commercial fronts operating under the influence and control of these officers. A prominent example is the business empire run by businessman Khodr Ali Taher—also known as “Abu Ali Khodr”—on behalf of Maher and Asma al-Assad, with ties extending to Bashar al-Assad himself and his advisor Yasar Ibrahim. The latter oversees a wide network of companies operating across multiple, intertwined layers of the economy, often with the help of his proxy, Ali Najib Ibrahim([9]).

These economic networks have served as a central tool for the regime to circumvent international sanctions, enabling officers and officials to continue generating vast illicit profits. This strategy allowed the regime to expand its economic reach, secure additional funding to reinforce its core power structures, and mitigate the impact of sanctions by relying on opaque commercial fronts and complex networks that are difficult to trace.

If these commercial activities are not exposed, many of these companies may eventually position themselves to benefit from Syria’s post-war reconstruction projects. By obscuring their direct links to security officers, they could gain access to lucrative contracts—allowing their owners, who played a central role in the country’s destruction by supporting the regime’s military and security approach since 2011, to profit from the rebuilding of the very infrastructure they helped dismantle.

Mechanisms for Uncovering Officer-Owned Companies and Networks

In the wake of the political shifts following the fall of the Assad regime, economic and security investigations have emerged as essential tools for dismantling the financial structures tied to regime officers and influential figures. These investigations are not solely aimed at legal accountability—they also seek to protect public resources and prevent the continued operation of looting networks and exploitative economic structures.

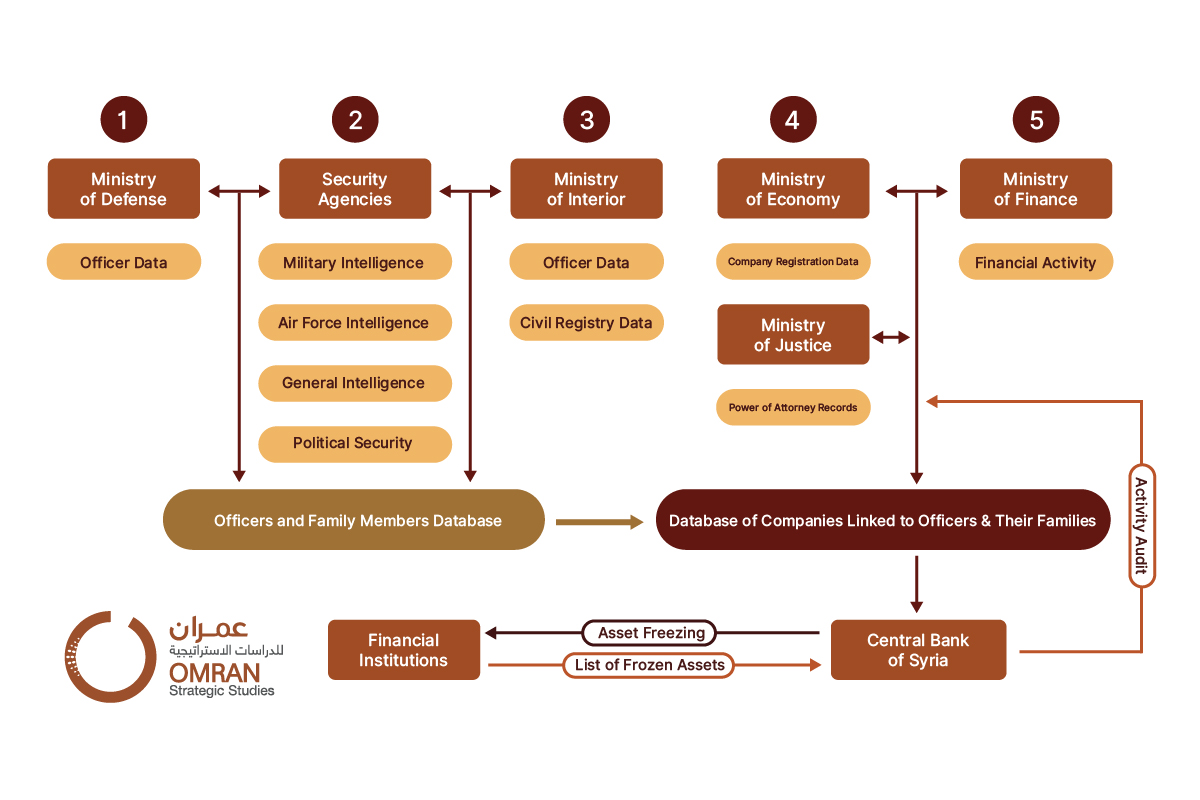

This mechanism begins with the collection of officer data from official databases—particularly those maintained by the Ministries of Defense and Interior, as well as the intelligence services. These entities serve as the primary sources for identifying officers and their official positions.

The next phase involves cross-referencing this information with civil registry records, in order to identify individuals related to these officers, including spouses, children, and siblings. This process enables the construction of a unified database linking officers to their family members, which can then be used to trace companies owned or partially controlled by them—whether directly or through indirect affiliations.

Data held by the Ministry of Economy—specifically the Directorate of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection, which is responsible for issuing business licenses. These names are then matched against the Ministry of Justice’s database to identify any corresponding legal powers of attorney. This intersection of data reveals companies owned by officers or their family members, many of which operate as fronts.

Once these companies are identified, detailed lists are forwarded to the Central Bank of Syria, which is then tasked with freezing their bank accounts and related assets as a precautionary measure, pending further investigation into their activities.

The Ministries of Finance and Economy play a joint role in this process by reviewing the financial and tax activities of the identified companies and investigating any violations or suspicious affiliations. If it is confirmed that these companies are linked to officers implicated in human rights violations—or to their family members—or that legal instruments authorize them to manage or sell assets, the relevant legal procedures are initiated to confiscate these assets in accordance with the state’s established mechanisms.

Figure (1): Mechanism for Identifying Officer-Owned Companies and Networks

This effort requires the establishment of an institutional framework that adopts the proposed mechanism and ensures coordination among relevant ministries and state institutions, drawing on data available in their official records. The objective is to create a unified database of companies registered in the names of officers, human rights violators, and their family members.

The process also necessitates technical and analytical support from specialized research centers with expertise in tracking networks of influence and commercial fronts. In this context, coordination with international bodies becomes essential to facilitate access to assets held abroad and to address the role of cross-border companies used to circumvent sanctions. The significance of this methodology lies in its contribution to transitional justice—through the dismantling of the economic structures underpinning the repressive apparatus and the prevention of their reconstitution in the future.

Future Measures to Determine the Fate of Regime-Affiliated Companies

Addressing the economic activities linked to former regime officers and officials requires a comprehensive strategic approach aimed at dismantling the networks that sustained the regime’s power. Commercial enterprises registered under the names of officers’ relatives or linked to them cannot be viewed as entities separate from the regime’s structure, nor should they be dismissed as “non-relevant” operations. Rather, these ventures operated within political and economic frameworks explicitly designed to reinforce regime control and secure its resources.

Accordingly, once these companies are identified in the initial phase, a series of follow-up measures can be initiated, including but not limited to the following:

Asset Freezing and Investigation of Economic Networks

The first step in addressing the economic activities linked to regime officers is the freezing of suspicious assets held by them and their family members. This measure should be implemented in coordination with international actors such as the United Nations and global financial institutions to ensure that both domestic and overseas assets are included.

It is recommended that a specialized legal and economic unit be established within the government to manage this file and carry out asset freezes effectively.

Reviewing Past Contracts and Projects

Reviewing the contracts and projects that have benefited these companies—particularly those linked to the state or international organizations—is a priority to prevent continued funding of these networks or their participation in future recovery and reconstruction efforts.

It is recommended that the aforementioned committee be tasked with auditing both government and international contracts signed since 2011.

Managing Frozen Assets

A clear and transparent plan must be developed for managing frozen assets in a manner that ensures their reinvestment in national development. Available options include: confiscating the assets and transferring their ownership to the state for use in development projects; restructuring the assets by converting them into productive enterprises that serve the public under government supervision; or redistributing the proceeds from asset sales to support public services such as education and healthcare. Alternatively, these funds could be directed toward reparations programs within the framework of transitional justice.

International Cooperation

The government should coordinate with United Nations agencies and countries supporting Syria’s political transition to ensure that assets located abroad are accurately identified and included in accountability efforts. This coordination may involve requesting technical and legal assistance to trace and freeze concealed assets. It is also advisable to broaden the scope of these efforts to include cooperation with international financial institutions to track financial flows linked to the former regime and ensure they are not used for illicit purposes.

Conclusion

These measures should be embedded within the broader framework of transitional justice, which seeks to achieve accountability and prevent impunity for perpetrators of violations—while focusing on dismantling the networks of corruption and exploitation that served as pillars of the former regime. The transitional phase provides the legal and moral foundation for addressing these companies and their beneficiaries, whether through judicial investigations, asset recovery mechanisms, or economic policies aimed at preventing the reemergence of financial influence rooted in the machinery of repression.

Moreover, integrating these efforts within the framework of transitional justice ensures transparency and accountability, while safeguarding the rights of all parties within fair legal standards. The ultimate goal of this process goes beyond accountability—it also includes protecting public resources and redirecting them toward national development. This requires the adoption of rigorous, data-driven methodologies and comprehensive investigations capable of uncovering companies linked to officers and officials implicated in human rights violations in Syria.

Appendix:

Interactive Figure (1), showcases examples of companies linked to security agencies, the military, and their family members.

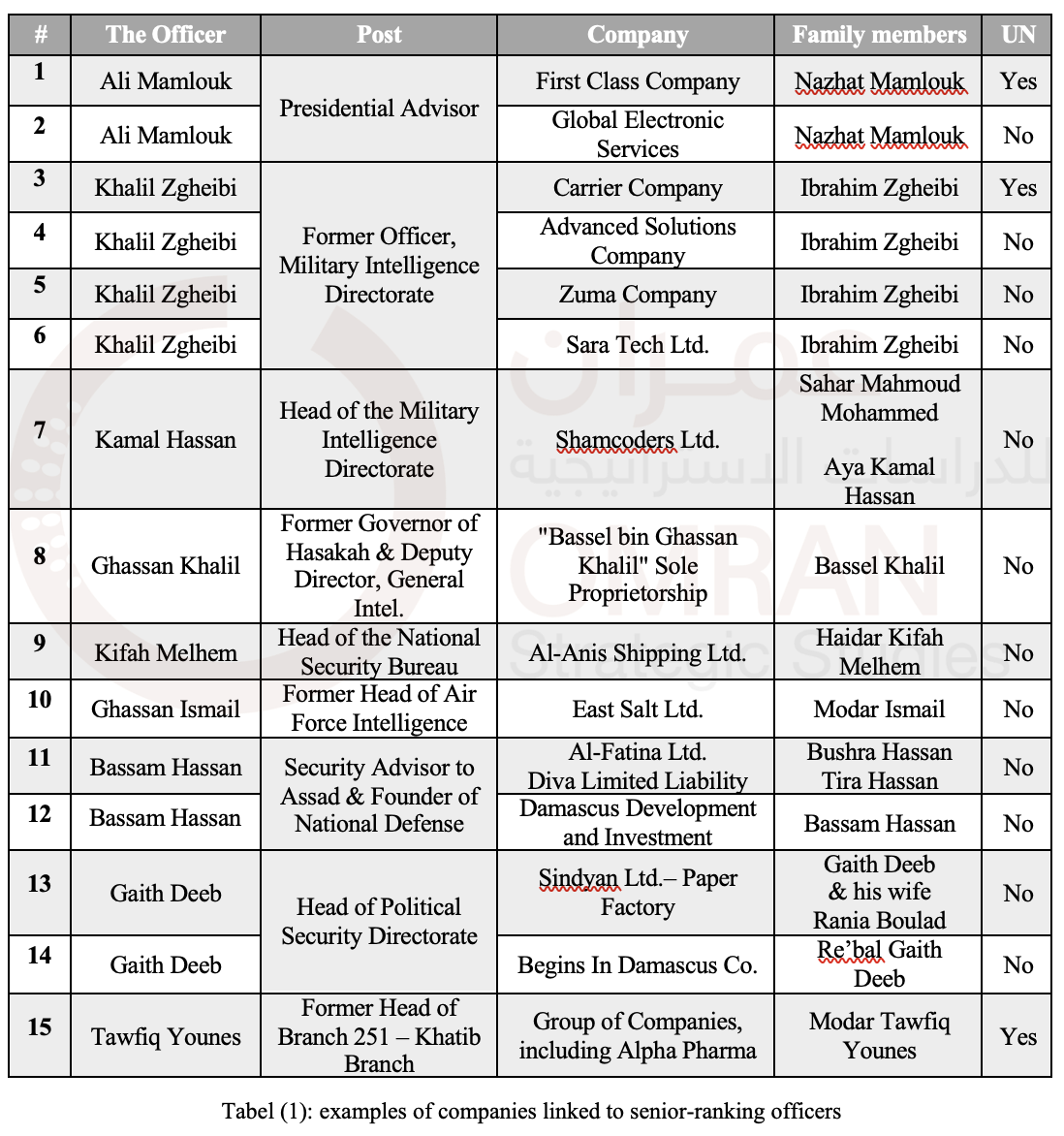

The following table provides examples of companies associated with senior-ranking officers from the security agencies, the military, and their family members:

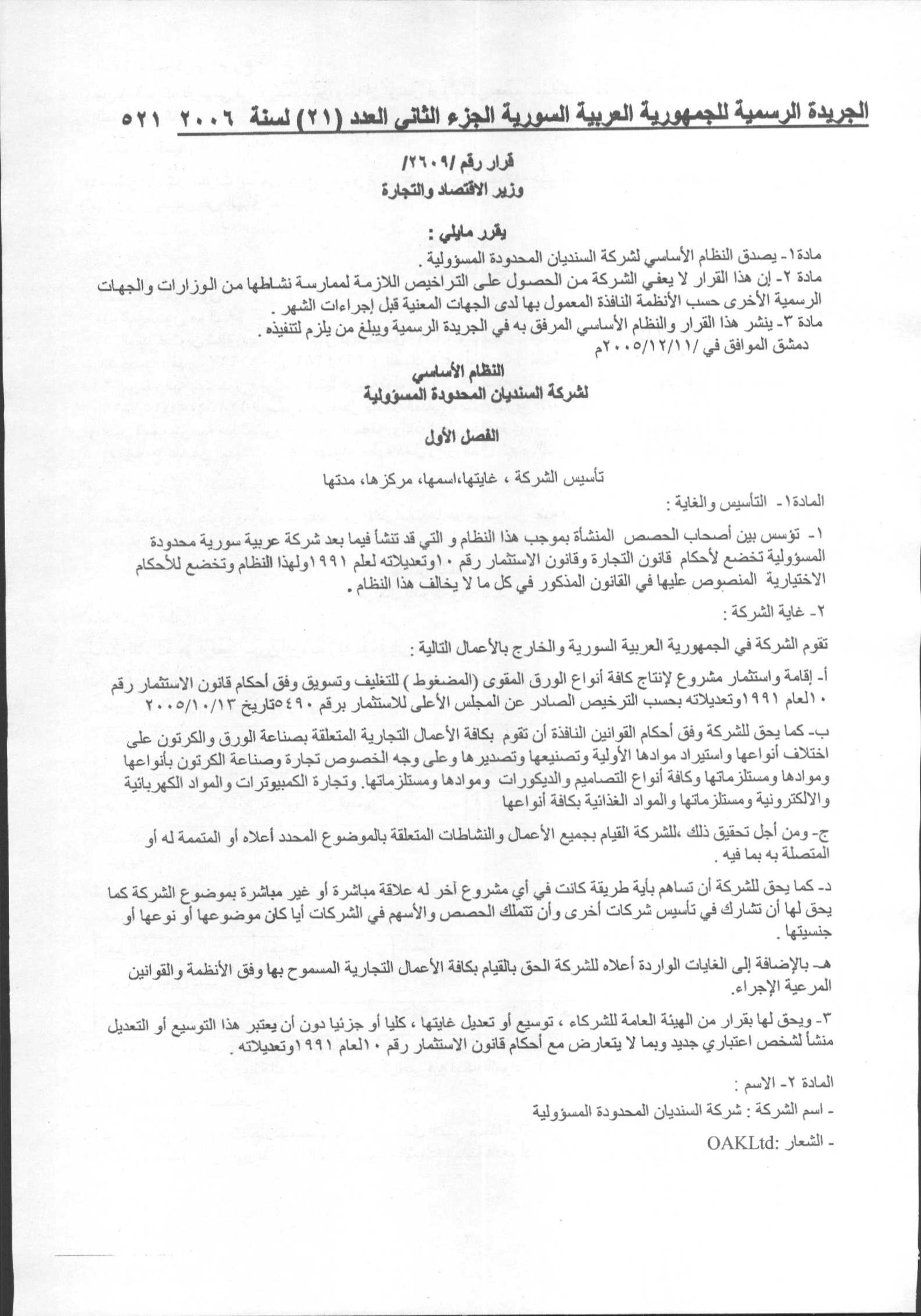

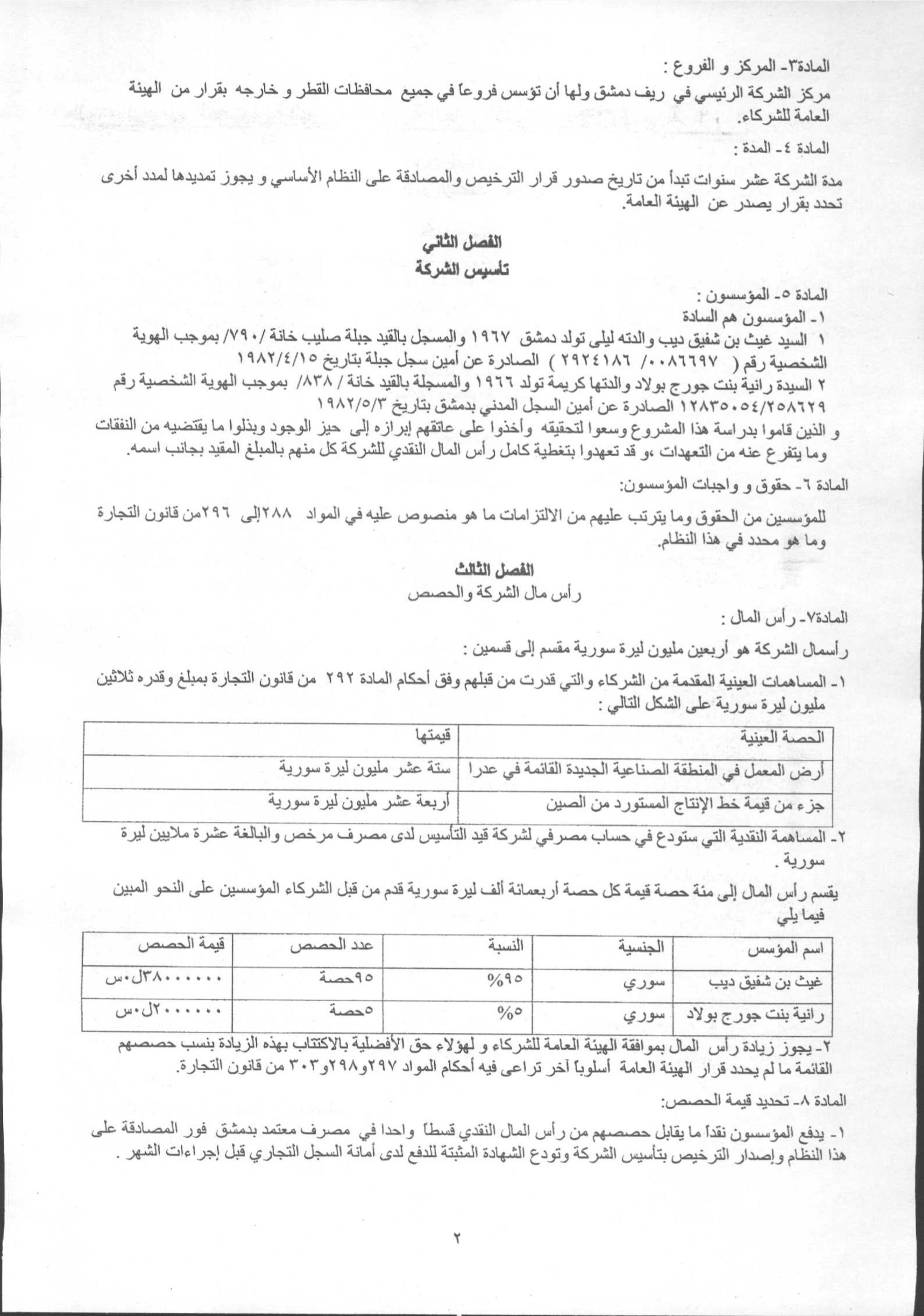

An example of one such company is Sindyan Ltd, owned by Major General Gaith Deeb and his wife, Rania Boulad. Established as a paper manufacturing plant in late 2005, the company’s initial capital exceeded one million USD—at a time when the exchange rate stood at approximately 50 Syrian pounds to the dollar. Notably, Gaith Deeb, who then held the rank of lieutenant colonel, had a monthly salary that did not exceed 200 USD at best.

An official document issued in the Official Gazette – Part II – Issue No. 21 of 2006

([1]) “Syria Orders Freezing of Bank Accounts Linked to Assad Regime” Al Jazeera Net, published on 23/01/2025. Link: https://bit.ly/4hvv9Xg

([2]) The Syria Sanctions Policy Program (SSPP) 2023–2024: An initiative by the Syrian Forum aimed at enhancing the effectiveness of Western sanctions on the Assad regime. Implemented in cooperation with the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks and the Omran Center for Strategic Studies. Link: https://bit.ly/42pam3o

([3]) “Legislative Decree No. 18 of 2003 – Military Service Law”, Syrian Parliament, published on 21/04/2003. Link: https://bit.ly/3GyL0Cq

([4]) “Fraud and Financial Extortion of Families of Detainees and the Forcibly Disappeared” , Association of Detainees and the Missing in Sednaya Prison (ADMSP), published on 16/11/2021. Link: https://bit.ly/40NGufH

([5]) “Shamcoders LLC,” Official Gazette, Issue No. 24, Part 2, dated 22 June 2023. Syria Report. Link: https://bit.ly/3PS8317

([6]) “UN Procurement Contracts in Syria: A Network of Corruption?” Observatory of Political and Economic Networks and the Syrian Legal Development Program, published in November 2022. Link: https://bit.ly/4hroi0Q

([7]) Diana Rahima, “How the Syrian Regime Pressures the UN to Hire Relatives of Its Officials”,Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, published on 10/03/2023. Link: https://bit.ly/4hxclXO

([9]) “A Syrian Craft: Assad’s Regime Uses Shell Companies to Evade Sanctions”, Syria TV, published on 22/03/2022. Link: https://bit.ly/3CnF0zA