The topic of early recovery is currently a focal point among UN circles and donor entities, as well as among Syrian parties, individuals, institutions, and organizations. In this context, the United Nations, through the Office of the Humanitarian Coordinator in Damascus, announced its approach to establishing an Early Recovery Fund. This announcement has been accompanied by leaks and rumors regarding the fund, its operational mechanisms, and its funding size. Additionally, the announcement has sparked reactions and discussions among donors and Syrians alike. This situation necessitates an initial analysis of this proposal, examining the opportunities it presents and the risks it entails, ultimately leading to recommendations that could guide the fund's operations and ensure the achievement of its intended goals.

Early Recovery: A Problematic Concept and a Syrian Perspective

The concept of early recovery in post-conflict areas is highly debated within humanitarian circles, NGOs, and among donors, primarily due to the absence of a standardized recovery framework for post-conflict scenarios. This gap contrasts sharply with the well-established frameworks for post-disaster recovery. The varying perspectives and distinct demands of stakeholders on early recovery in Syria contribute to its dynamic nature, and continuously shaped by both political and humanitarian considerations throughout the stages of conflict. This puts forward a unique opportunity for Syrians to develop an approach that reflects their specific realities in a more holistic methodology.

In 2008, the United Nations Early Recovery Cluster published its initial Guidance Note on Early Recovery, defining it as "a multidimensional recovery process initiated from a humanitarian context, guided by development principles aimed at leveraging humanitarian programs to foster sustainable development opportunities. The objective is to cultivate self-reliance mechanisms, uphold national ownership, and ensure resilience throughout the post-crisis recovery phase. This process includes the restoration of all essential services such as livelihoods, shelter, governance, security, rule of law, and environmental and social dimensions, with a particular focus on the reintegration of displaced populations(1)Also, TheGlobal Cluster for Early Recovery (GCER) offered an expanded definition, describing early recovery not merely as a phase but as “a thorough, multidimensional process that commences early in the humanitarian response. It focuses on bolstering resilience, restoring, or enhancing capacities, and addressing enduring issues that contributed to the crisis rather than exacerbating them, alongside a suite of programs designed to aid the transition from humanitarian relief to development.(2)While The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) characterized early recovery as “an approach that meets recovery needs emerging during the humanitarian phase of an emergency, where saving lives remains a critical and immediate priority. Early recovery initiatives support affected communities in safeguarding and reinstating essential systems and service delivery, building upon initial response efforts, and establishing a foundation for prolonged recovery. The outcomes of these early recovery efforts include creating robust foundations for resilience post-crisis, fostering sustainable development solutions led by national or local entities, and rebuilding community capacities(3).

From these definitions, it is evident that Early Recovery is a multidimensional approach that builds on humanitarian response, aiming to stabilize communities and enhance their adaptive capacities. However, there is debate about the content and scope of early recovery. De Vries and Specker argue that early recovery is a period between the humanitarian phase during and immediately after a conflict and the medium to long-term development phase. While some researchers and humanitarian agencies define the first three years after the end of a conflict as the timeframe for early recovery, according to the UNDP program, early recovery can begin even before the conflict parties reach a political settlement(4).

Early recovery in post-conflict situations is closely associated with the stakeholders involved in recovery and their interests. This makes the transition from conflict to peace not merely a technical approach and practice but a highly political process in which principles, priorities, and concepts vary. This variability is highly evident in the Syrian context and explains the diversity of approaches to this concept. Some argue that the early recovery process should begin once the conflict has ended, in response to attempts by the Syrian regime to initiate this process before achieving a political solution. It aims to establish peace and stabilize “state institutions” through a mix of different policies. There are at least four main threads that form the foundational concepts of “early recovery.(5)

- Humanitarian aid frameworks;

- Economic growth and development;

- Peacebuilding and human security;

- Governance models and state-building.

Conversely, The Operations and Policy Center (OPC) defines early recovery by comparing it to the concept of reconstruction as: “An activity that lies between the prevalent approach focused on basic humanitarian aid (food, shelter, water and sanitation services, hygiene) on one side and reconstruction on the other. Its priorities are arranged according to humanitarian needs, similar to other forms of humanitarian aid, which are planned and implemented by relief organizations, whether they are centralized under a single administrative authority like the United Nations or individual organizations.” Meanwhile, a study by The Day After (TDA) adopts the following definition for early recovery: “All the humanitarian and developmental efforts made by local and international entities to improve the economic and social conditions across the country, in addition to the efforts made in enhancing the effectiveness of institutions involved in improving these conditions. Thus, early recovery activities include supporting essential services such as health and education, projects supporting private sector work and employment opportunities, and initiatives promoting social cohesion.(6)

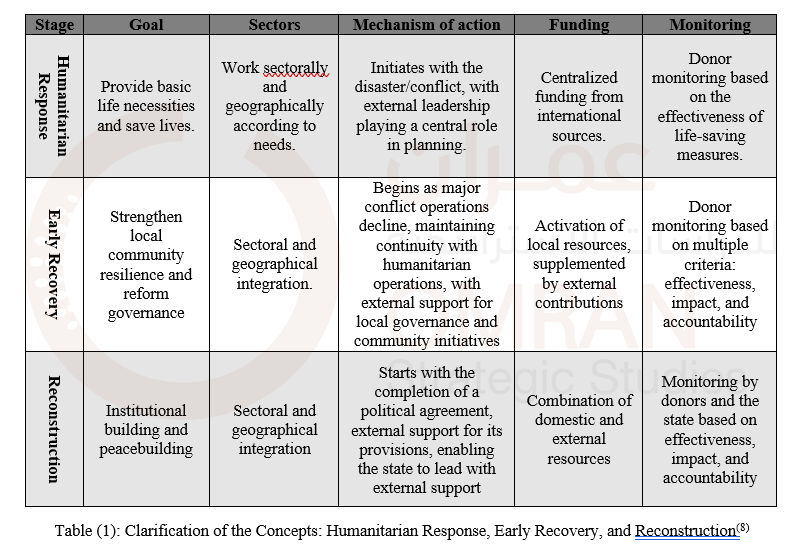

To clarify the concept, it is necessary to delineate the boundaries between early recovery and related concepts such as reconstruction and humanitarian response, which can be summarized in the table below.(7)

Based on the above, early recovery is considered a late stage of humanitarian intervention that commences as major military operations wind down. It increasingly depends on local communities and governance structures to manage the planning, funding, and implementation processes, with support from external actors. The primary objective of early recovery is to enhance the stability and adaptive capacity of local communities through projects that are integrated both sectorally and geographically. These projects are evaluated based on criteria of effectiveness, impact, accountability, and transparency(9)

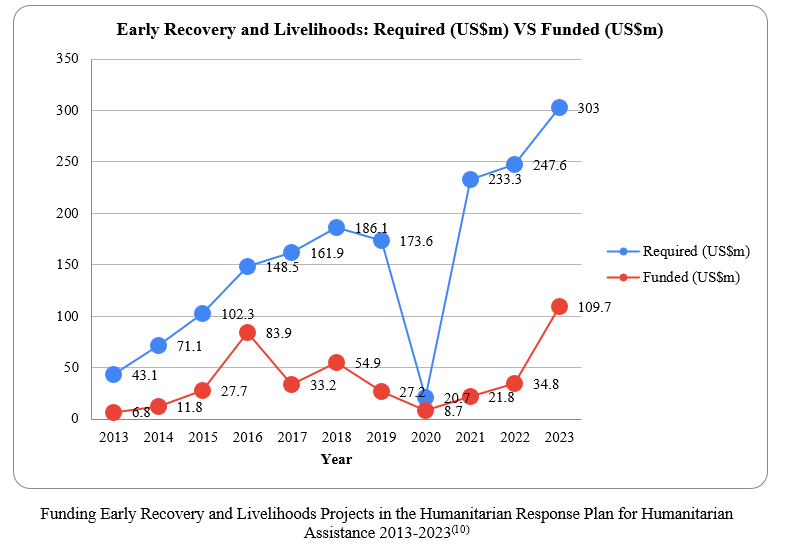

The Early Recovery Trust Fund (ERTF): A UN Initiative with Political Content

Political negotiations among actors in the Syrian crisis, alongside the associated risks and repercussions of regional and international crises, have placed early recovery for Syria on the agendas of the United Nations and its donors. This has led to the development of a UN strategy to establish a trust fund for early recovery, although some aspects of this strategy are still being refined. Since 2013, early recovery and livelihoods have been recognized as a distinct cluster within the Syrian Humanitarian Assistance Response Plan (SHARP). From that year until 2023, the total funds requested for these projects amounted to approximately $1.691 billion, of which $420.5 million, or 24.8% of the total required, has been funded.

Funding for early recovery and livelihood projects between 2013-2023 has been limited by Western countries and the United States. They have adhered to the three "Nos": NO normalization with the Syrian regime, NO lifting of sanctions, and NO engagement in reconstruction without a political transition according to UN resolutions. This stance likely stems from their desire to continue pressuring the regime to advance the political negotiation process toward a resolution. This is in conjunction with existing humanitarian response mechanisms, exemplified by the cross-border aid mechanism established in 2014 under UN Security Council Resolution 2156.

Since 2020, discussions on early recovery have shifted due to a decrease in major military operations, the impact of political negotiations among actors in the Syrian crisis through various pathways and initiatives, and objective considerations related to the growing humanitarian needs amidst declining funding for the Syrian crisis. Moscow exerted pressure to modify the cross-border aid mechanism, initially reducing it to two crossings (Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salam/Resolution 2504), and later to just one (Bab al-Hawa/Resolution 2533), with a focus on early recovery projects as defined by Security Council Resolutions 2585/July 2021, 2642/July 2022, and 2672/January 2023. These resolutions identified early recovery sectors including water and sanitation, healthcare, education, shelter, and electricity, providing early recovery efforts with a legal framework and UN legitimacy. Since 2021, attempts at normalization with the Syrian regime have gained momentum, characterized by the "step-by-step" approach, which was conceptualized by some think tanks and supported by Jordan and UN Special Envoy Geir Pedersen, where early recovery was one of its focal points(11)

The following determinants and objectives laid the groundwork for the UN proposal of the Early Recovery Trust Fund:

- Exploring solutions to a deadlock in the political process, especially as the Constitutional Committee meetings stalled since 2022, and the UN's interest in testing an economic-humanitarian approach to achieve a political breakthrough and advance the stalled negotiation process;

- Managing challenges of the Syrian crisis, particularly with the suspension of the cross-border aid mechanism since July 2023, and declining funding for humanitarian response at a time when humanitarian needs are expected to rise (UN estimates that 16.7 million people in Syria will need assistance in 2024), possibly linked to changing donor priorities under the pressure of regional and international crises;

The relaxed stance of the US administration towards Arab efforts to normalize and communicate with the Syrian regime, and the exceptions granted from sanctions (June 2021, May 2022, February 2023), and earlier flexibility with Russian demands to include early recovery in Security Council resolutions, which provided leeway for Arab initiatives towards Damascus, indicating the possibility of funding early recovery projects if Damascus complies with specific steps.(12)

Humanitarian diplomacy to overcome sanctions and activate the Arab role: This was evident in the aftermath of the February 2023 earthquake and the diplomacy of disasters through the role of the UAE as a mediator, achieving a bilateral agreement between the UN and the Syrian regime to introduce UN aid through border crossings with Turkey outside the UN mandate(13)as well as the UAE's use of the earthquake disaster to circumvent sanctions imposed on the regime and send aid to it, thereby laying the groundwork for proposing a secure and legitimate mechanism under a UN umbrella for Arab donors to support early recovery projects, away from the constraints of US and European sanctions, as indicated by the UN Coordinator for Humanitarian Affairs in Syria, Adam Abdelmoula(14)

- Conversations led by Martin Griffiths, Deputy Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, with the Syrian regime post the February 2023 earthquake framed the UN proposal for the Early Recovery Trust Fund initiative, culminating in a decision by the UN Secretary-General in June 2023, directing the UN team in Syria to prepare a five-year early recovery program, including a clear plan for securing its funding. The war on Gaza and concerns about its implications for regional stability, specifically Syria, the regime's stance towards it, and what can be relied upon from the Early Recovery Trust Fund to influence the relationship between the regime and its allies, particularly Iran, were factors that paved the way for the UN proposal, overcoming any US or Western opposition.

The draft conceptual note for the UN’s ERTF defined it as an additional mechanism alongside existing ones (Syria Humanitarian Fund (SHF), Syria Cross-border Humanitarian Fund (SCHF)). The objective of ERTG would be to secure funding outside the humanitarian response plan for early recovery projects over five years (until 2028) based on the following priorities that would help build the adaptive capacity of local communities: health and nutrition, education, water services and sanitation facilities, livelihoods, and electricity. The fund consists of a steering committee, a technical committee, and a secretariat initially based in Beirut, with the Resident Coordinator and the UN Coordinator for Humanitarian Affairs in Syria leading and coordinating the overall management of the fund in consultation with donor entities and participating organizations. As for funding the fund, governments, international governmental and non-governmental organizations, and private sector organizations were identified as contributors to this fund, with several sources indicating that the initial ceiling of the fund would be $500 million over five years, noting a lack of enthusiasm from the United States and Europeans to fund this initiative. However, many points remain subject to questioning, especially regarding the role of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the World Bank in managing this fund, the possibility of increasing the funding ceiling in the future, the stance of Gulf countries towards this fund, as well as the role of the Syrian regime in this fund, and the fair distribution of early recovery projects across influence zones.

ERTF: Identifying Risks and the Need for Guiding Principles and Standardized Frameworks

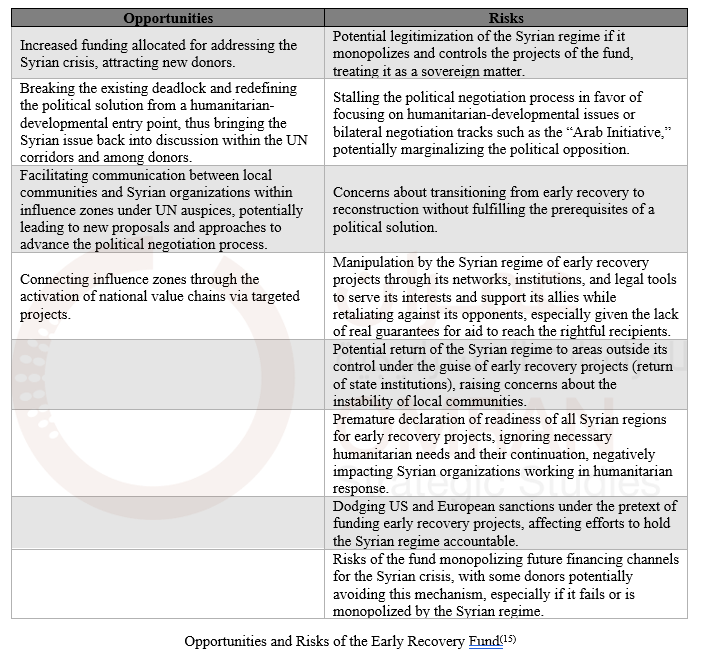

ERTF offers significant opportunities but also encompasses considerable risks, necessitating the implementation of guiding principles and standard frameworks for fund governance to ensure its effective contribution to achieving stability and advancing the political negotiation process. Concerns raised by numerous Syrian experts, organizations and political bodies, intersect with those by some donors regarding the fund's operation and its expected outcomes. These concerns stem from the UN’s previous experiences in Syria, marked by diminished transparency and manipulation by the Syrian regime to further its own interests.

The opportunities and risks of the fund can be summarized in the following table:

Strategies to Ensure Effective Implementation of ERTF

United Nations:

- Govern and manage the ERTF in a wise, neutral manner and seriously consider a neutral location for the fund, ensuring that projects cover all geographical areas of Syria without restrictions and guarantee the involvement and utilization of Syrian organizations’ capacities in the process, including monitoring, guiding, and implementing.

Syrian Organizations:

- Enhance the capacities of Syrian organizations to respond to early recovery projects, and incorporating this even in their humanitarian response.

- Ensure the voice of Syrian organizations in early recovery through: 1) Launching advocacy campaigns in major capitals at all levels to prevent the Syrian regime from monopolizing the process and redirecting it towards its interests, 2) Organizing workshops and events to discuss early recovery and formulate a common ground on the issue, 3) Developing an index to classify regions based on their needs and readiness for inclusion in early recovery projects, with continuous updates and sharing results with relevant entities, 4) Integrating the roles of Syrian organizations concerning early recovery, and their efforts to build alliances across influence zones to ensure a positive impact on this process.

Donors:

- Avoid granting the Syrian regime free gains without extracting substantial concessions that enhance stability and advance the political negotiation process.

- Bind the United Nations to the following guiding principles for early recovery projects: 1) Aimed at supporting the stability and adaptability of local communities, 2) Capable of connecting influence zones and activating national value chains, 3) Implementing early recovery projects in a decentralized manner that considers the local context of each region, 4) Ensuring that external actors facilitate and support the process, not lead it, enhancing local ownership and engagement.

- Emphasize to donors that while the Early Recovery Fund is an important mechanism to support stabilization efforts, it is insufficient on its own, and the continuity of other response mechanisms for the Syrian crisis must be maintained.

([1])UNDP Policy on Early Recovery, United Nations Development Programme, 22 August 2008. https://bit.ly/31aEU66

([2]) Global Cluster for Early Recovery (GCER), United Nations Development Programme, https://shorturl.at/ntMR1

([3]) Strategic Framework for Early Recovery, Risk Reduction, and Resilience (ER4), USAID'S BUREAU FOR HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE, October 2022, https://shorturl.at/jqtQ5

([4]) Dr. Salam Saeed, Early Economic Recovery in Syria: Challenges and Priorities, in the book Economic Recovery in Syria: Actors Map and Evaluation of Current Policies, Omran Center for Strategic Studies, 25.09.2019. https://shorturl.at/eCDJN

([5])Osama Al-Qadi, Correcting Perceptions. OSHA and "Early Recovery"!", Syria TV, 26.04.2021. https://shorturl.at/cfg79

([6]) Sami Akil, Karam El Shaar, Early recovery and reconstruction in Syria between reality and politics, 07.02.2022. https://shorturl.at/ABL57

([7]) Zaki Mahshi, Mohammed Al-Sattouf, The impact of early recovery and reconstruction projects on housing, land, and property rights in Syria. 30.01.2024. https://shorturl.at/lrzNS

([8]) A workshop hosted by the Omran Center for Strategic Studies, featuring Syrian experts, took place in Istanbul on April 16, 2023.

([9]) See Reference 8

([10]) Financial Tracking Service – OCHA. Syrian Arab Republic Humanitarian Response Plan. https://shorturl.at/rzPY7

([11]) Like, A Path to Conflict Transformation in Syria. A Framework for a Phased Approach. Carter center. Jan 2021. https://bit.ly/3ZDEe8o, and d Raphael Parens and Yaneer Bar Yam. Step by Step to Peace in Syria. New England Complex Systems Institute. 09 Feb 2016. https://bit.ly/3kjb4v1

([12]) Ibrahim Hamidi, Al-Majalla publishes the Jordanian Initiative for Syria... Three phases end with the exit of Iran and Hezbollah, Al-Majalla, June 25, 2023, https://shorturl.at/vEFV9

([13]) Laila Bassam, Ghaida Ghantous, Maya Gebeily and Tom Perry. Exclusive: Assad approved Syria quake aid with a UAE nudge, sources say. Reuters. 23.02.2023. https://shorturl.at/cmGT5

([14]) Muwaffaq Mohammed, extends for 5 years and includes projects including electricity, and is financed through a special fund. And enthusiasm for the contribution of Gulf countries ... Abdel Mawla to Al-Watan: Before the summer, we will launch an early recovery program, Al-Watan, 31.03.2024. https://shorturl.at/djFPZ

([15]) See Reference 8