Executive Summary

- The uprising in Al-Suwayda Governorate reached its eighth month by April 2024, advocating for economic improvements and political transition in Syria through the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 2254. The protests called for the overthrow of the regime and the removal of its security hold over the city, including demands to shut down Ba'ath Party headquarters. The extent of the protests has fluctuated, expanding, and contracting in response to shifts in the dynamics of the movement in Al-Suwayda and the varying positions of spiritual and religious authorities after the first month. The three religious’ leaders, Hikmat Al-Hijri, Hamoud Al-Hannawi, and Yousef Al-Jarbou, unanimously agreed on the necessity of economic reforms. However, Sheikh Yousef Al-Jarbou's stance more closely aligned with the Assad regime's narrative in the governorate. He also led the Druze religious authority during regime events, coinciding with his regular meetings with leaders of several militias opposing the movement in the governorate.

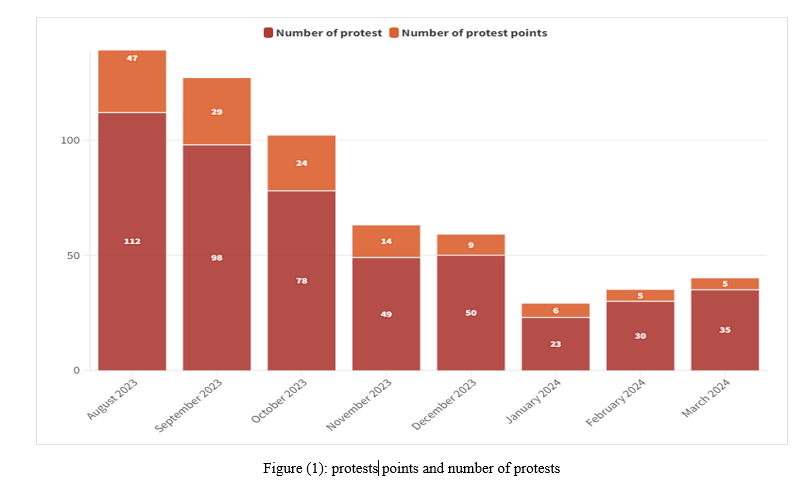

- The protests peaked in August 2023 but gradually subsided, eventually concentrating in Karama Square in Al-Suwayda and the towns of Al-Qrayya and Salkhad. The decline can be attributed to the shift of people from the rural areas of the city towards the main squares to intensify the gatherings. Additionally, militias active in the eastern and western rural areas of the governorate resumed their involvement in drug trafficking to the Jordanian borders. These militias have threatened the movement several times, fearing that the protests might threaten their trade or that they might later be targeted by the protesters themselves.

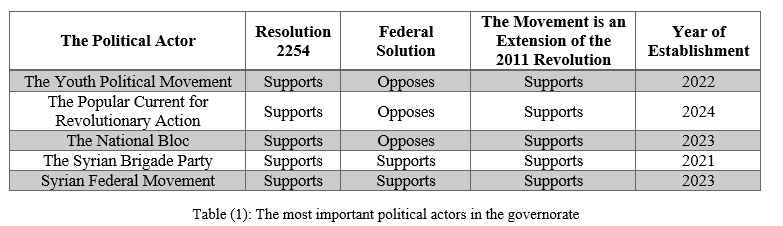

- The disagreement among the political factions in the governorate manifested in the proposed administrative structure of Al-Suwayda. All political factions in the governorate agreed on the necessity of economic reforms. However, the suggestion by the Syrian Brigade Party and Syrian Federal Movement to federalize Al-Suwayda was a point of contention for the other factions, who viewed it as an attempt to impose a political vision on the movement that would lead to a partial political solution not encompassing other Syrian provinces.

- The anticipated scenarios for the movement fall within three main axes: The first is the proposal by the Syrian Brigade Party to implement federalization in Al-Suwayda as an administrative solution for the governorate. This solution is seen as a threat to the movement because it is associated with the experience of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Northeast Syria, which opened a confrontation front with the Turkish government, as it threatens Turkish national security. Additionally, the movement is regarded as another separatist attempt in southern Syria, giving the Assad regime a pretext to use violence in the governorate. The second scenario involves the movement's ability to create shared spaces either with other regions, aiming to align local demands with national demands that extend beyond the geography of the provinces outside regime control, or even to initiate dialogue with neighboring countries concerning their security concerns, such as the production and smuggling of Captagon, particularly concerning Jordan. The third scenario sees the regime continuing to operate on a no solution basis while the effectiveness of Captagon smuggling routes in the governorate continues. This, combined with the lack of expansion of the movement, might prompt militias involved in the trade to destabilize the city's security if the movement becomes a threat to their smuggling operations.

Introduction

The uprising in Al-Suwayda Governorate continued into its eighth month by April 2024, demanding economic improvements and political transition in Syria through the implementation of Resolution 2254. The protests have called for the overthrow of the regime and an end to its security grip on the city, including demands to close the Ba'ath Party headquarters. This paper aims to examine the events in Al-Suwayda from July 2023 to March 2024, analyze the map of actors influencing the movement, understand its extension and response to security changes in the region, evaluate the role of religious authorities, and explore future directions for the field scenario in Al-Suwayda.

Changing Intensity of Protests and Multiple Factors

Since the beginning of the uprising, the extent of the protests in Al-Suwayda has varied, influenced by changing security and field events that the movement has undergone. Additionally, the varying stances of the spiritual authorities after the first month have influenced some of the movement's demands. These authorities have unanimously agreed on the necessity of economic reforms in the governorate, while their positions on the political demands related to political reform and the implementation of Resolution 2254 have differed.

Sheikh Youssef Al-Jarbou's position has closely aligned with the regime's narrative in the governorate(1). He criticized the political demands of the demonstrators as incorrect and led the Druze religious authority during the regime’s events and activities from August 2023 to February 2024. On October 12, 2023, he participated in the morning of the martyrs of the Military College in Homs.(2) Sheikh Youssef also held frequent meetings with Safwan Abu Saad, the governor of the Damascus countryside, who is originally from Suwayda, and dealt with local militias that posed a threat to the movement and protesters in the city. His dealings with the leaders of the Saif al-Haq militia, Radwan and Muhannad Mazhar, who were heavily involved in drug trafficking and security unrest, were of particular importance(3).

While Sheikhs Hamoud Al-Hannawi and Hikmat Al-Hijri's positions were closer to the popular movement, they varied in their opposition to the regime's authority in the governorate. Sheikh Hamoud Al-Hannawi participated in several protests and supported the public demands, urging people to demand their rights in a clear and bold voice. Meanwhile, Sheikh Hikmat Al-Hijri remained committed to his narrative that the political and economic demands of the protesters must be met, alongside his calls for local factions to protect the movement, thereby preserving civil peace and preventing the protests from turning into violent conflicts between the protesters and the regime forces in Al-Suwayda. The divergence in the positions of religious authorities, on the one hand, and the Assad regime's choice of a no-solution strategy, relying on time to diminish the movement after the protests failed to expand beyond Al-Suwayda to Daraa or other regime-controlled cities, on the other hand, led to a shift in the momentum of the protests in terms of number and spread across the villages of the governorate.

Figure (1) shows that the protests peaked in August 2023, after which the protest sites gradually receded to concentrate mainly in Karama Square in Al-Suwayda and the towns of Al-Qrayya and Salkhad. The decline is attributed to people moving from the rural areas of the city towards the main squares to intensify gatherings, especially on Fridays. Additionally, militias active in the eastern and western rural areas of the governorate returned to their activities in drug trafficking and its transfer to the Jordanian borders. These militias have threatened the movement several times, fearing that the protests might jeopardize their trade or that they might later be targeted by the demonstrators themselves.

Efforts to Organize the Movement and the Interwoven Demands

Some community elements in Al-Suwayda began organizing themselves into political entities with the onset of the Syrian revolution in 2011, but most remained inactive due to the specific conditions imposed by the city on Assad's regime behavior towards it. The regime avoided direct confrontation with local factions or religious authorities to ensure that a southern opposition pocket comprising Al-Suwayda, Daraa, and Al-Qunaitra did not form against it. Additionally, these entities did not join the traditional opposition represented initially by the Syrian National Council and later by the Syrian Coalition. However, as the movement in Al-Suwayda crystallized over several waves, the longest of which began in August 2023, some political components in the governorate became more active, and their demands became clearer, organized around three axes: the administrative structure of the governorate and its relationship with the central authority in Damascus, the nature of the required political reforms, and the extent to which the demands align with those of the 2011 revolution and international resolutions, especially Resolution 2254, which mandates a political transition in Syria.

Table (1) illustrates the key political actors in the governorate and their positions on the previously mentioned axes. It shows a consensus among political entities on the necessity of political transition, affirming that the popular movement in the governorate is part of the broader narrative of the 2011 popular movement with similar political and economic demands. However, the political disagreement among these components lies in their divergent views on Al-Suwayda's role within Syria's governance structure. The Syrian Brigade Party, established in 2021, believes that federalization is the most effective solution for political reform in Syria. This view is supported by several local political currents in the governorate, along with the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) based in Northeast Syria, which welcomes the proposal. This proposal aligns with their broader vision of implementing a federal solution in Syria and exporting it to other regions like Al-Suwayda, thus potentially strengthening the SDC narrative if it can export its model to other areas with unique ethnic or racial characteristics. (4)

The popular movement has sustained its demands for political change and necessary economic reforms, alongside efforts to disassociate the Ba'ath Party from the state apparatus in the governorate. Protesters have moved towards permanently closing the party's headquarters or even converting some into public service facilities. This is juxtaposed with a strong emphasis on the need to protect state service institutions, which should remain neutral and not become entangled or influenced by the ongoing protests.

Protesters have closed several Ba'ath Party headquarters in Al-Suwayda city and its countryside, totaling 27 headquarters by the beginning of March 2024. Ten of these were transformed into service centers for the citizens of the governorate(5)In response, the Assad regime maintained its narrative that the presence of the party's headquarters is linked to the presence of service institutions in the city, which led it to reduce the operational capacity of its service institutions as a reaction to the closure of the party's headquarters. As the popular movement continued, demonstrators gathered in front of some service institutions and closed some of them in protest against their nominal and ineffective role in the governorate(6).

Regarding the stance of political actors in the movement, they attempted to protect state institutions, emphasizing their neutrality, and ensuring they were not targeted. However, some political currents sought to create alternative service and security bodies in the city. The Syrian Brigade Party initially established a Counter-Terrorism Force led by Samer Al-Hakim, but this initiative was met with a security campaign by the regime's Military Security, which resulted in the disbanding of the force and the killing of Al-Hakim in June 2023. Subsequently, the party announced the establishment of several service offices such as a water authority, a rapid medical intervention office, and civil defense. These establishments were part of the Brigade's efforts to introduce the concept of self-administration to the movement, capitalizing on the service vacuum left by the regime's absence in the city. However, the idea of these institutions did not gain popularity among other political currents due to their rejection of a partial political solution limited to Al-Suwayda rather than extending to other Syrian provinces.

Local Scenarios within a Turbulent Regional Environment

Since its inception, the Al-Suwayda movement has been closely tied to rapidly changing regional dynamics, manifesting in three main areas: first, the trade and production of Captagon; second, the normalization process with the Assad regime; and third, the presence of Iranian forces in Syria and the increasing frequency of Israeli attacks on these forces. Future regional changes could also influence the expansion or contraction of the movement based on the positions of neighboring countries regarding the proposed scenarios. On the local level, the potential scenarios include three possibilities: the risks associated with proposing self-governance, the movement's ability to open new spaces for cooperation both internally and externally, and the potential for the movement to be dominated and redirected.

· The First Scenario involves the Syrian Brigade Party's proposal for federalism in the city, which poses a risk to the movement by associating it with the SDF experience in Northeast Syria, which has opened a confrontation front with the Turkish government. This proposal also raises fears that the movement could be viewed as another separatist attempt in Syria, similar to the SDF's demands for an independent area, thereby strengthening its international stance in advocating for turning Syria into federations. This scenario would provide the Assad regime with a pretext to use violence in the province to assert control over Al-Suwayda under the guise of protecting Syrian territorial integrity. Previously, the Assad regime had no clear justification for using violence against the movement due to the unique demographic composition of the city and its reliance on two elements for the movement's decline. The first is linked to local groups causing security disturbances, and the second bets on time for the movement's recession and cessation if the demonstrators fail to form political forces or establish a national coordinating framework among all regions outside Assad's control.

· The Second Scenario entails the movement's ability to create shared spaces with other areas, aiming to align local demands with national demands that transcend the geography of the provinces outside regime control. This could involve transforming economic and political demands into a unified discourse, potentially revitalizing the political process, or even initiating dialogue with neighboring countries to address their concerns. An example of this is reassuring Jordan, which considers the smuggling of Captagon from Syrian territories as one of the most significant threats to its national security and is seeking solutions to halt its flow across its borders.

· The Third Scenario is based on the regime's reliance on a no-solution approach, while the effectiveness of Captagon smuggling routes continues in the province. With the Al-Suwayda movement not expanding beyond the governorate, local militias linked to the regime and Iran might destabilize the city's security if the movement threatens their smuggling operations. These militias are integral parts of the Captagon supply, production, and smuggling chains.

In conclusion, it is not possible to definitively predict one scenario over others without considering international variables, such as the war on Gaza and the ongoing Israeli raids on Iranian positions in Syria, as well as the perspectives of local political currents on the future of the movement and the city. The proposal for federalization within the movement would face Turkish opposition to prevent the Al-Suwayda movement from becoming a lever that the SDF might later exploit. Additionally, the way Jordan handles the Captagon issue and its potential coordination with local factions like the Men of Dignity Movement (Rijal Al-Karama) could protect the movement and open up other cooperative prospects with Jordan, potentially having economic or political dimensions in later stages. The challenge for the movement's coordinators and local factions remains in their ability to present a political front that reflects their demands and is consistent with the broader Syrian context, particularly as regional countries shift their focus in Syria to security motivations after previously supporting the movement and its political demands.

([1]) Contrary to Druze references: Sheikh Yousef Jarbou confirms his alignment with the Syrian regime, Al-Quds Al-Arabi, 30/08/2023, https://bit.ly/3J4naBg

([2]) Yousef Jarbou in Homs to condole the regime for the casualties of the "Military College," Al-Souria Net, 12/10/2023, https://bit.ly/4cHbGRR

([3])Suwayda: Groups linked to Military Security threaten to suppress the movement, Al-Madina, 09/11/2024, https://bit.ly/3vWaM3q

([4]) SDC supports the demands of Al-Suwayda protesters for self-administration and holds the Syrian government responsible for the deteriorating conditions, Al-Yawm TV, 21/08/2023, https://bit.ly/4aKKa4C

([5]) The pages of political currents, Al-Suwayda 24 page, and several local news networks were monitored, and data was cross-referenced among them during the period from August 2023 to March 2024.

([6])Protesters shut down several government departments and institutions, including the Directorate of Telecommunications and the Directorate of Agriculture, in protest against "the lack of response from government bodies to the demands of the citizens in Suwayda," Al-Suwayda 24 Facebook page, 05/11/2023, https://bit.ly/4aGTqpV