Centralization and Decentralization in Syria: Concepts and Practices

Introduction

After seven years of conflict between the people and the Assad regime, Syria is now going through a difficult phase. The nature of the conflict has transformed whereby the role and effectiveness of local actors has been greatly maringalized compared to an increasing role for international state and non-state actors. The role of armed opposition factions has diminished as international military, administrative, and political influence has grown. These armed opposition actors are also in a phase of turmoil as they struggle to survive or integrate under direct international custodianship, after having previously received support from the Northern or Southern Operations Rooms. This process follows the series of meetings in Astana and Sochi, and after the political bodies were domesticated into official negotiating bodies that support the interests of countries with direct influence over them. At the same time, direct Russian influence came to dominate the political, military, economic, and administrative spheres. As a result, the concept of the unified framework of the "regime platform" versus the "opposition platform" in accordance with the Geneva II concept was discarded through the creation of several negotiating platforms on the sides of the opposition, the regime, and the Syria Democratic Forces (SDF).

At the same time as these political changes were happening, the areas of influence and control on the ground were consolidated in 2018 into the north and northwestern portion under Turkish control, the northeast under the U.S. and SDF control, and southwestern Syria under the influence of the U.S. and Jordan, allowing Israel to strike any sites that it deems threatening. The areas of siege and opposition group control have been eliminated. International and regional influence has thus become more distinct, as efforts to control and integrate both armed opposition and pro-government groups continue.

This new phase is characterized by a complex series of partial deals that build on one another, and the arrangements among the state actors are developing in a "step by step" policy approach. The "counter-terrorism" framework that was used to justify the entry of these countries into Syria, is no longer a justification for their continued presence and influence: the U.S. is increasingly focused on the "Iranian threat;" Turkey is focused on "fighting the PKK" and security its borders; Israel justifies its interventions with the need to protect its borders against the "Iranian threat" and to prevent the transfer of weapons and fighters toward its borders; and Jordan is now also interested in protecting itself against the “Shi’ite crescent".

In light of this new landscape, contributing writers to this book discuss several aspects of Syria's current form of governance and how experiences on the ground in the different areas of influence converge or diverge from the concepts of centralization and decentralization, both vertically and horizontally. Towards this end, the chapters of this book first clarify the concepts and forms of decentralization and the way they are applied in post-conflict countries. They highlight the important role that agreeing on the form of governance and power sharing is an important factor in maintaining territorial unity and in shepherding negotiations to a more relevant stage of the new post-conflict reality. Next, the authors delineate decentralization in terms of its political, security, financial, and developmental functions, and review the constitutional and legal foundations of administrative and political decentralization in Syria. Finally, the authors present the experiences and applications of governance since 2011 in the regime-controlled areas and opposition-controlled areas, as well as in the SDF-controlled in northeast areas of the Democratic Autonomous Administration. Woven throughout the book are comparative descriptions of the experiences from Iraq, Lebanon, and other countries emerging from conflict, to see what lessons can be learned from the ways that these countries have negotiated the distribution of powers between central and local administrative units.

This book aims to help lay out a path towards the restoration of the legitimacy lost by all parties in Syria through the organization of local governance tools based on the experience of local councils. Local councils have tended neither towards excessive forms of decentralization nor to authoritarian centralization, but have instead followed a path that strengthens local structures and sets limits to central state authorities by granting powers rather than delegating them. At this stage, it is essential to work in parallel on strengthening the central government while also safeguarding and reinforcing the gains of the local councils through constitutional guarantees and a new local governance law. This book also stems from recognition of the need to shift away from limited centralized negotiations among the two “sides of the conflict” through a constitutional process followed by general elections, towards a negotiation based on power-sharing arrangements. Local governing bodies and other local actors should be engaged in the process of deciding which functions and authorities are mandated to the central institution versus the local governing units.

The chapters of this book were contributed by several researchers who differ in their approaches, but they all agree on the need to develop a decentralized Syrian model that avoids the reductive binary approach of political decentralization / administrative decentralization or federalism, and one that is based on the sharing of powers and functions, thus transitioning Syria’s system of governance from local administration to local governance. There is no doubt that further development and discussion of these ideas is required, but we present this effort as a starting place for a dialogue in the Syrian community on the most authentic or locally developed form of governance for Syria, which after years of adhoc decentralization, has become more localized than ever before.

Finally, it is important to note that most chapters were written in late 2017 and early 2018, which was before the change of control of Damascus suburb, northern Homs and the southern front. The arguments for a tailored and customized Syria-centric decentralization model put forth are still valid regardless of the controlling armed party.

Executive Summary

Chapter one of the book focuses on the concept of decentralization and illustrates the differences among countries when it comes to choosing how they exercise administrative authority. Every country’s approach to governance is influenced by its political and social conditions, as well as the maturity and depth of its democratic practices. The need to shift towards a decentralized system becomes apparent after examining factors related to a state’s nature, size, and degree of political stability. Decentralization becomes a necessity for stability in some countries because of its core idea: the distribution of power and functions of state institutions between the central governments and local administrative units. This conceptualization reaffirms the fact that the transformation to fully decentralized system may be risky for many governments, despite the promise that decentralization holds as the solution for most conflicts in developing countries such as those in the Arab world. Chief among these problems is the need to expand the political and economic participation of citizens. Still, given the ethnic and sectarian diversity and complex nature of countries, decentralization can be a threat to state unity.

Chapter two describes political functions of the state in a decentralized system and how it is practiced in different versions of decentralization. Political functions of the state take many forms depending on the degree of decentralization and mode of local governance. The far end of a decentralized governance system continuum appears in the practice of full political decentralization (full federalism), where provinces and regions have their individual constitutions and laws, exercise special legislative, executive, and judicial powers, and influence federal government policy through a political oversight authority and through their representatives in the legislative branch councils. Local governments, meanwhile, exercise specific roles in these functions under the partial political decentralization within their constitutionally-vested authority. These roles are primarily related to domestic policy-making and the development of local rules and regulations that do not contradict federal legislations. In administrative decentralization modes of governance, the practice of political functions and duties is reduced to a great extent as it focusses exclusively on administrative and executive functions of local governing institutions. Local administrative units would then be fully subordinated and controlled by the central administration in the capital. In partial administrative decentralization modes of local governance, political functions completely disappear from local units.

According to chapter three of this book, the exercise of legislative and judicial functions within a decentralized system will require reforms in the Syrian judicial branch, such as: the restructuring of the Supreme Judicial Council to ban the executive branch from holding membership in it and stop its interference, and the repeal of laws that encroach on public rights and freedoms with judicial not executive branch oversight. Assessing the current form and content of the Syrian Constitution in terms of centralized or decentralized approaches highlights centralism as highly visible and grants authority to the presidency (which has broad constitutional powers) to override all other authorities and functions of the state. Instead, the principles of separation and distribution of powers should be applied to three independent bodies in order to create balance and cooperation between them. With regard to legislative duties in Syria, this paper shows that the Constitution has broadly granted legislative duties to the People's Council of Syria (Parliament) and the President of the Republic, transforming the mandate of the Parliament from drafting laws to ratification of presidential laws. Reforming this imbalanced structure requires redefining the scope and mandate of the Parliament, abolishing the broad powers granted to the President, and reducing the centrality of legislation process and parliament. There needs to be a shift toward some kind of decentralization that divides future legislative functions in a balanced approach between the exclusive jurisdiction of the legislative branch, and the jurisdiction of the executive branch for all that is not stated in text of the constitution.

The fourth chapter focuses on security functions in decentralized systems. In the context of conflict-ridden or post-conflict countries, it is critical and necessary to re-assess national security functions: their applications, mechanisms for implementation and governance, and how security roles are distributed at different levels of government. This paper emphasizes that the redistribution of security duties and authorities in decentralized countries (in accordance with the lessons from stable and unstable countries) may result in a more efficient and coherent security architecture depending on who and how such a process is executed and whether by means of national actors, cross boarder actors, or international actors. In the search for a governing framework of the Syrian security sector within a decentralized system, independent intelligence agencies should have a clear mandate of intelligence gathering only (except for police forces and anti terrorism units that can arrest citizens) and an identified geographical jurisdiction. Local governing bodies should be constitutionally mandated to provide local security services and conduct police functions and duties locally. The assessment and identification of security threats and risks and the counter strategy to such risks should be developed locally and shared with central agencies for coordination.

The fifth chapter highlights the dialectical relationship between decentralization and its role in local development in countries emerging from conflict. Local development is one of the most important determining factors in whether or not decentralization is adopted in these cases. While some of post-conflict countries have reached acceptable rates of economic and social development after moving to a decentralized system, others have not. This disparity may be due to factors linked to each country’s particular local development process and adopted form of decentralization. This paper emphasizes that in the context of the Syrian situation, the country has suffered from the absence of a clear developmental model for decades. This has led to major developmental imbalances at the central state level, which are most evident in the developmental disparities between Syrian governorates. The adoption of a model of administrative decentralization in Syria will help to mitigate this disparity by empower local communities to participate in the local development process.

The sixth chapter, which deals with financial decentralization, emphasizes the fact that the successful implementation of decentralized systems of government in post-conflict countries depends largely on their ability to establish regulatory frameworks for financial decentralization and mechanisms for the collection, distribution, and disbursement of financial resources at various levels of government and administration. Successful implementation also requires substantial reforms in fiscal policy in general and in spending policies in particular. This paper finds that that the model for allocating financial resources to the local administrative units out of the state budget in Syria has many flaws. It is necessary to grant administrative units greater financial independence and to define metrics for successful financial decentralization to measure whether these units are meeting developmental requirements and making effective contributions to economic and social stability in their regions.

The seventh chapter examines the reality of local administration in regime-controlled areas. It illustrates the dominance of the central government in the local administration systems in regime-controlled areas, the growing influence of the Baath party, and the increasing influence of local Iran-backed forces in the operations of some local administrative units. This paper finds that the service sector crises in the areas of local administration units are indicative of their lack of funding, dysfunctional mechanisms, and insufficient personnel, forcing them to rely on the central government to conduct their affairs. It also argues that the regime is not interested in decentralization – which runs counter to its desire to retain centralized control – but it does use decentralization politically as a bargaining chip for negotiations with the international community, particularly the Europeans. The regime also attempted to manipulate the boundaries of the electoral constituency of administrative units to change administrative districts and weaken opposition areas by preventing them from winning elections in their areas while rewarding loyalists.

The eighth chapter focuses on the reality of governance in Syrian opposition-controlled areas. It reaches several conclusions, the most important of which is that local councils have undergone changes in terms of structure, mechanisms of formation, and function, as their organizational structures have stabilized and they rely increasingly on the elections for their membership. They have also been able to consolidate their service roles, compared to their role in local security and politics. The financial file is one of the primary challenges facing local councils as they cope with growing financial deficits, due both to the nature of revenues and expenditures, and also their lack of financial systems or laws regulating their budgets. This chapter explains how the long duration of the conflict, the transformations in its nature, the push towards coexistence, and the survival of the regime have all stimulated competition between local actors, of which the local councils were one of the most prominent players due to their political value and local legitimacy. As a result of the way the local councils have dealt with these challenges and threats, they face one of three scenarios in the foreseeable future: vanishing entirely, forming regional or cross-regional self-administrations, or continuing the current independent local units structures.

The ninth chapter analyzes the reality of governance in the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. It shows that lack of transparency is a key feature of service delivery, financial administration, and the management of strategic resources within the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. The process of forming legislative councils (mandated to pass laws) in these areas was based on partisan consensus that relied primarily on the literature and system of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM). Laws passed by these legislative councils, such as laws related to self-defense, changes to school curricula, and civil status laws, are problematic. A review of the structure of the DAA and its legislative and executive bodies, shows the presence of a partisan political project that is being forced on the local population through its security and military apparatuses. This paper concludes that the DAA, though able to impose a unique governance model, still suffers from problems of representation, legitimacy within its population, and a lack of competent personnel, and it has failed to eliminate the local and regional concerns arising from this project.

The tenth and final chapter of this book proposes a unique Syria-customized decentralized framework, one that takes into account the importance of achieving stability. It highlights the importance of refocusing international negotiations on two parallel tracks: negotiations policies to strengthen central state institutions in order to create conditions for peace and stability, and empowering local governance models through local negotiations on power sharing of authorities and functions of the central state with local administrative units. They must also revisit the basic Geneva Communiqué according to the principle of power sharing agreements between the center and periphery and not only a central agreement where the opposition and regime share authority. This means prioritizing internationally-monitored elections over any other track, beginning with local administration elections.

In order to ensure the success of the elections, essential actions are required from the different parties with regards to the restoration of the functionality of police and local courts. It is therefore necessary to begin drafting a new law for local administration (decentralization) to allow locally-elected authorities to have full control over the work of the police and administration of local courts.

The opportunity exists for local councils to legitimize their structures and negotiate new authorities, guaranteeing a decentralized model that provides expanded authorities to the councils and governorates, based on the strength of their electoral legitimacy. This chapter emphasizes the need to empower the tools and foundations of local governance both constitutionally and legally, and to ensure that the countries with a presence on Syrian soil help push the negotiations to a peace-building stage and guarantee relative stability on the ground until an agreement on the various security arrangements is concluded.

for More Click Here: http://bit.ly/2B2Vxqd

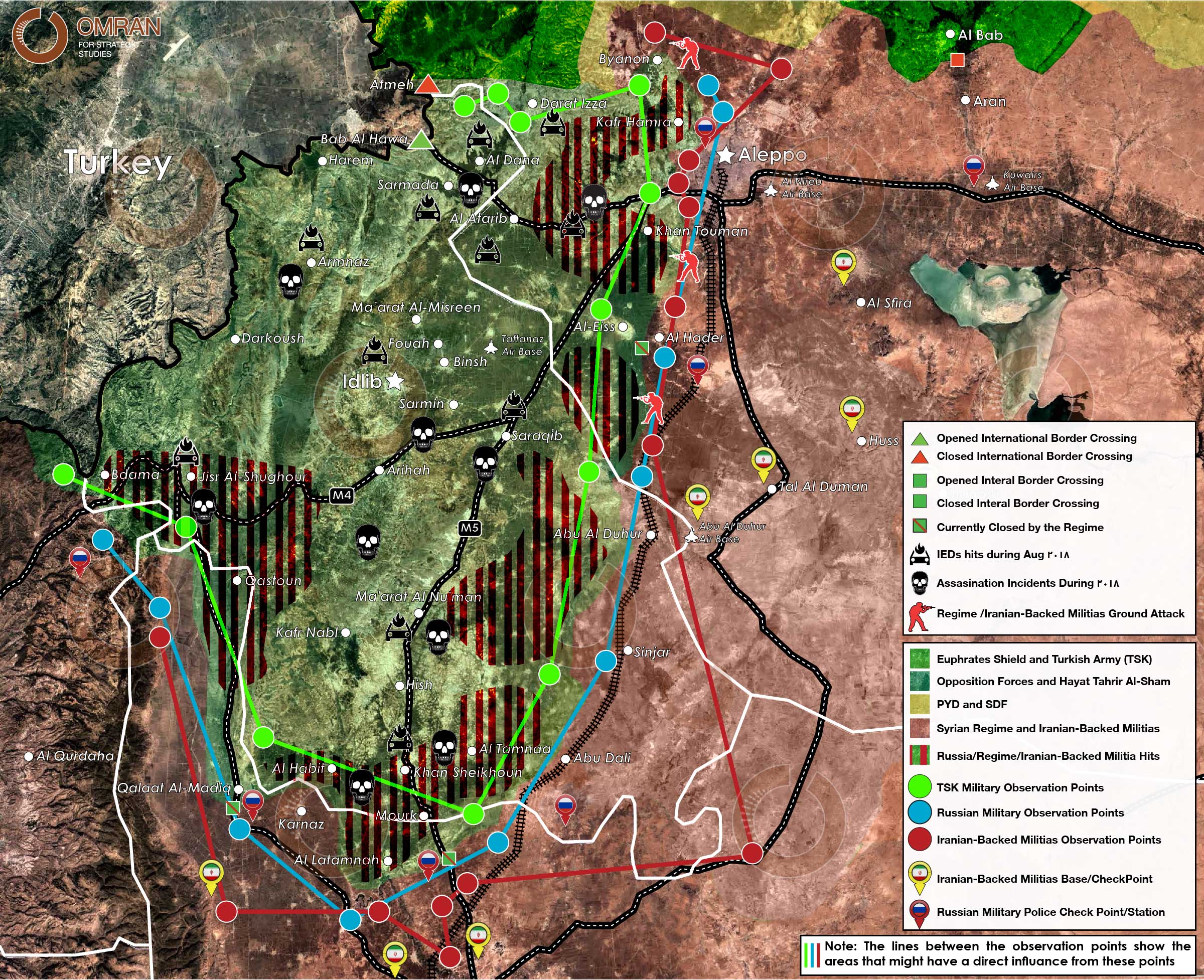

Area of influence Map of Idlib and its surroundings

Map 1: Updated situation map of Idlib, western Aleppo and northern Hama

- Iranian-backed militias’ military bases.

- Russian military police checkpoints around Idlib province.

- International Highways crossing Idlib province (M4 and M5).

- International border crossings with their current operating status and internal border crossings with their current operating status.

- Areas targeted by regime forces, Russian air force, and Iranian-backed militias’ artillery in August 2018.

- Sites of IEDs and assassination incidents that occurred in Idlib and western Aleppo Province in August 2018.

Notes:

- M4 and M5 highways are considered one of the main strategic targets for any possible attacks from the Regime and his Iranian allies.

- Internal border crossings are trading hubs between areas under regime control and areas under opposition control. Currently these borders are closed by the regime for different reasons, except "Qalat Al-Madiq" in Sahel Al-Ghab was partially opened in the last few days to allow the last IDPs convoy from the south to enter Idlib.

- On 13 August, Russian Military Police took over both "Qalat Al-Madiq and Mourek" corresponding internal border crossing sites in regime areas replacing the Syrian Army’s 4th Division (Affiliated with Iran).

Dr. Ammar kahf talking about Turkey's Idlib Operation

Dr. Ammar Al Kahf on 7th of October talking about Turkey's Idlib Operation, he said that there was a delay of the operation in order to contain elements from HTS "Al Qaida" and not to start a fight with them in order to save many life's of civilians, he added that the Astana agreement and three partners "Turkey, Russia and Iran" have different objective and this is not a strategic alliance in any way, but a very tactical step by step approach on containing the HTS forces at the time been, on the issue of Assad there is a political process that’s under going, and he is already lost credibility because of the fact that Russia and Iran are speaking on behalf of the regime and the his not on the table, he ended saying that there are life to save in Idlib and the agreement in Astana says that no Iranian or Russian troops will enter Idlib but they will be in charge of the border control of the de-escalation zone, he also added that one of the major objective in Idlib is to block any SDF advancement from Afrin.

De-escalation Zones: A Cloak to Refocus on the East

Executive Summary

-

The de-escalation zones from the latest Astana meeting on Syria aimed to freeze the conflict on the western fronts in order to deploy the regime and its allies’ forces to prevent a total loss of the eastern territories to the American-led Kurds and opposition forces. Securing Tehran-Baghdad-Damascus-Beirut free passage is strategically more important compared to Idlib or Ghota at the moment.

-

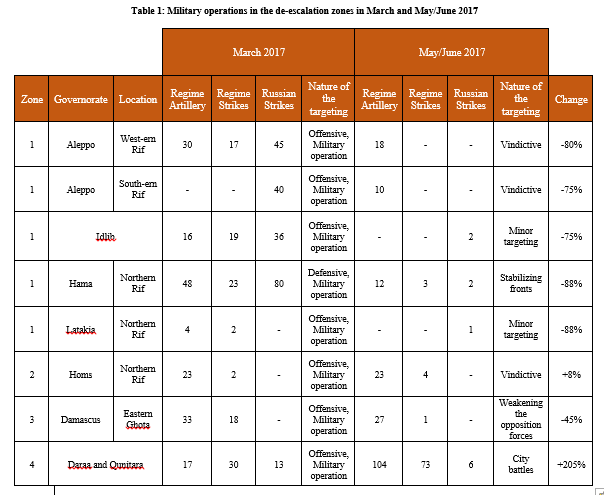

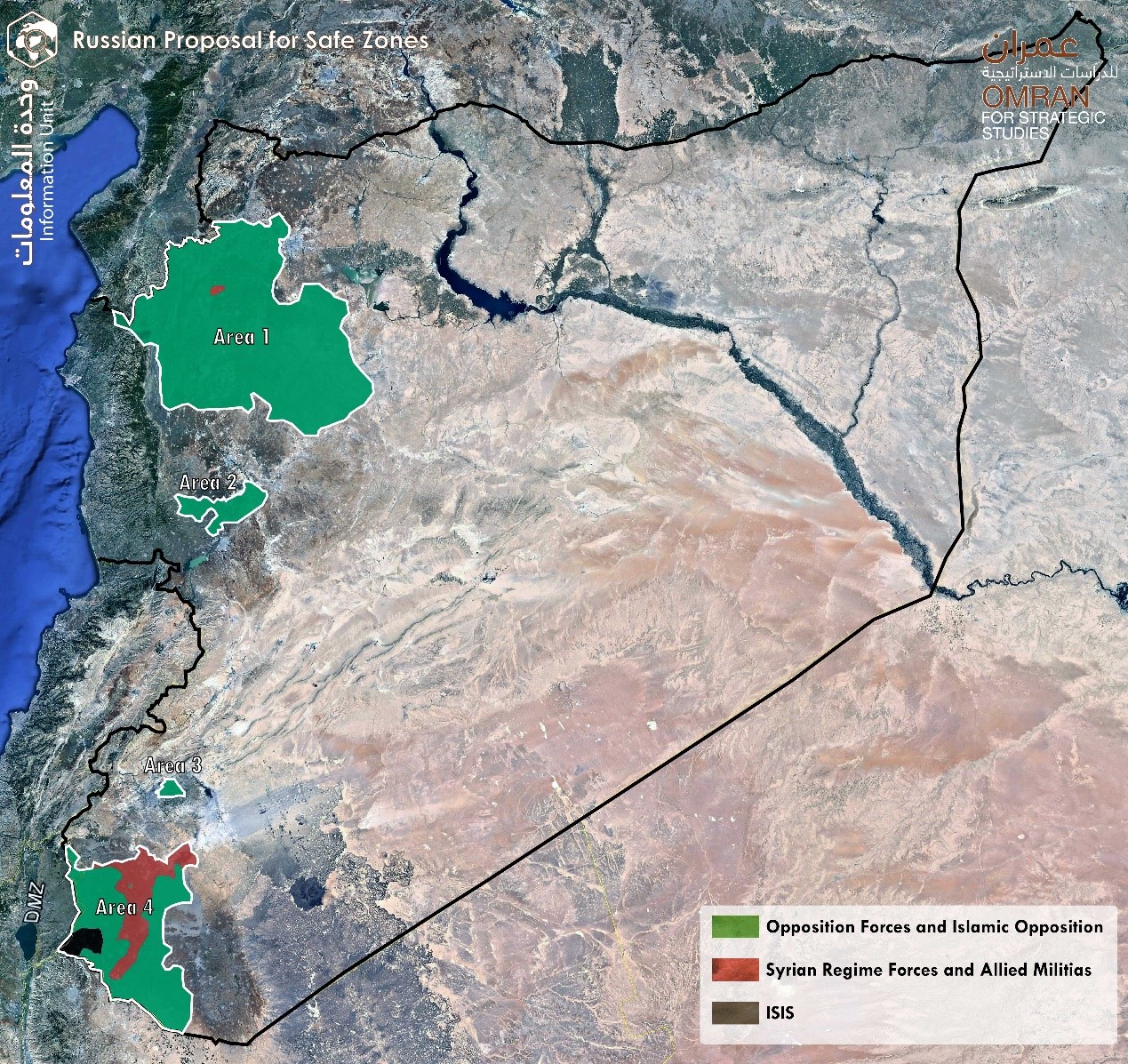

The agreement was largely observed by all parties (Russia, Turkey, and Iran) and resulted in an immediate reduction in military operations in the selected zones. Compared to the level of operations in March 2017, May/June 2017 witnessed an 80% reduction in western Rif of Aleppo, 75% in Eastern Rif of Aleppo, 97% in Idlib, 88% in Hama, 80% in Latakia, and 45% in Ghota of Damascus. There was a slight rise in military operations in Homs (8%) and a radical increase in Daraa (205%) but that increase was mainly attributed to vindictive offenses like in Homs, or tactical deterrence to the opposition as in Daraa’s al-Manshia district.

-

The latest Geneva talks ended with no significant outcome, probably in anticipation of settling the current competition over Raqqa and Dir Ezzor. It is unlikely for Geneva to restore its significance before stabilizing the military situation and before the US and Russia move towards a serious political settlement.

-

It is still too early to determine if the de-escalation zones can serve as a basis for a Russian strategy to stabilize the situation on the ground and foster an environment conducive to a political solution. The outcome of the battles on the ground in the East and the sustainability of ceasefire in the West will determine such an outcome. Neither easy nor quick dominance in the East is in sight for either side. Particularly because of the proxy nature of the operations, lack of cohesion between the participating forces, and unprofessionalism of the local forces aligned with the Americans (Kurds and opposition forces) and Russians (tribal forces and Fifth Corps).

-

Nor will there be a clam west, as HTS (al-Nusra coalition) will aim to expand and exhaust the moderate forces with potential reactions from the latter. Accelerated foreign contact, including by the Russians, with the Local Administration Councils (LACs) in the de-escalation zones is expected in order to secure influence during the transition period.

-

This paper argues that the political opposition should unite its negotiations delegations and increase its capacity and legitimacy. The military opposition should support the political process and provide views on its role in the future. The LACs should focus on their service delivery role and improve their capacity to meet the tasks of reconstruction and return of refugees. More important for the Local Councils is to avoid local politicization and alignment with either regional or global actors in order to protect their neutrality as guarantors of a stable future for Syria.

-

The US and EU should support forming a united negotiation delegation for the opposition as a political solution might be looming on the horizon, especially after the situation in a post-ISIS Raqqa and Dir Ezzor settles down. Notably, engagement in Russian-led Astana talks is important to develop critical ideas on a US-EU/Russia cooperation in the transitional period.

-

Russia should support the legitimacy of the opposition delegations and refrain from undermining their efforts to effectively represent their Syrian constituency. More strategically, Russia should approach to the Local Councils, support their professional service delivery, and coordinate with their EU sponsors to assure fruitful cooperation in preserving their role in the future.

Map No. (1) Russian Proposal for Safe Zones

Introduction

The latest two peace negotiation rounds on Syria ended with postponing the serious discussions until after the dust settles in the east of Syria. The Astana meeting in Kazakhstan produced an agreement on de-escalation zones, supported by Russia, Turkey, and Iran and opposed by Syrian opposition representatives. Not surprisingly, the Geneva talks did not break the low ceiling of expectations and ended where it started. The de-escalation zones serve Russian interests on many fronts, the most important of which is freezing the West “hot spots” (Idlib, Hama and Homs) to focus on the eastern front where Russia aims to disturb the American-led operations to recapture Raqqa and Dir Ezzor on the border with Iraq. The post-ISIS-controlled areas constitute the next battleground and are, to a large extent, the determinant of the final balance of power among all parties in future negotiations. While the eastern fronts will be fluid and hardly stable, the western fronts will not be calm either.

A few weeks before signing the agreement in Astana, there was an immediate reduction in military operations in the selected zones. Compared to the level of operations in March 2017, May witnessed an 80% reduction in western Rif of Aleppo, 75% in Eastern Rif of Aleppo, 97% in Idlib, 88% in Hama, 80% in Latakia, and 45% in Ghota of Damascus, according to the information unit at Omran Center. Some exceptions to the main reduction in hostilities were observed in Homs (8%) and Daraa (205%), with some vindictive offenses in Homs and tactical deterrence of the opposition forces occurred in Daraa.

The opposition forces (i.e., HTS, Ahrar al-Sham, and some MOC-affiliated militias) in late April has occupied al-Manshiya district in southern-Daraa and threaten to advance further into the regime controlled areas in Daraa; therefore, the regime aims to stop their advancement by redeploying forces from around Damascus after solving the problem of Qaboon and Barza cities. The Ghaith al-Dalla forces of the fourth division have joined the Shite militias in the south (Hizbullah, Iranian Revolutionary Guard IRG, and the Fatimioun brigades) to stop the opposition advancement beyond al-Manshiya using aggressive, rather tactical, deterrence offenses. (see Table 1 for more details).

This paper addresses the context of the de-escalation zones and provides an overview of the situation in all of the active fronts in the east and west of Syria. It also includes three sets of recommendations to the Syrian opposition (Political, Military, and LACs), as well as recommendations to 1) the US and the EU and 2) Russia.

The analysis concludes that both the Russians and Americans rely on forces that lack central coordination, professionalism, and discipline. Such characteristics weaken control over the operations, hence making it almost impossible to predict their outcome and trajectory. This turbulent and cloudy situation will dominate for an extended period, given the absence of a political framework to accommodate ISIS members after their organization collapses and they escape to new havens. In turn, the western fronts will be busy with HTS attempts to expand geographically and weaken the moderate opposition politically. There also will be an international and regional race to influence the LACs, considered the black horse in any future efforts for stabilization in the de-escalation zones through humanitarian aid, the management of the return of refugees, and reconstruction shall security guarantees are offered.

Information Support Unit, Omran Centre for Strategic Studies

De-escalation in the West, Escalation in the East

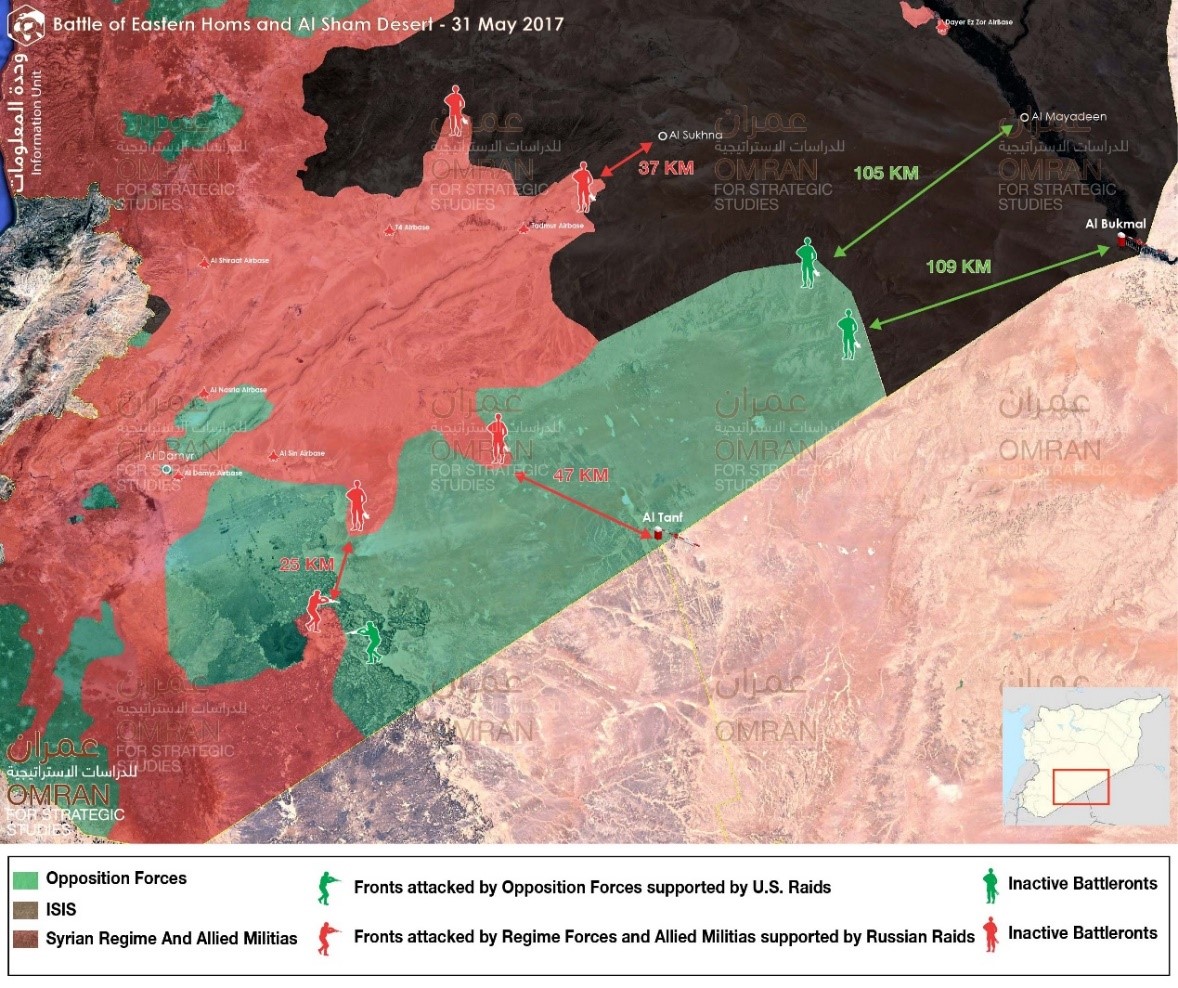

While attention is refocused on Raqqa and Dir Ezzor in the east of Syria, the latest agreement signed in Astana helps to freeze the western fronts in order to reallocate resources and concentrate forces for the upcoming battles in the East. The fall of both Raqqa and Dir Ezzor to America’s proxies limits Damascus’ control over the borders, cuts Iranian routes from Tehran to Beirut through Baghdad and Damascus, and empowers America’s grip over both Iraq and Syria.

The protracted war has exhausted the regime forces and devastated its capabilities, and the long line of active fronts in the West has distracted its allies’ attention to the slow developments in the East. The advancement of the Syrian Democratic Forces towards Raqqa and the Southern Front opposition forces towards Dir Ezzor alerted the regime to a near loss of the borders with Iraq. There was a severe need to reallocate the regime from Idlib and Homs, where they can revert to them later, to the eastern fronts, where it is more pressing to secure a foothold.

The new battle needs more manpower and expertise. For these, the Russians and Iranians rushed to organize the tribal forces and integrate them into the Fifth Corps under Russian command. Hizbullah has recently, and rather quickly, given its positions in the South to the Russians and its positions on the Syrian-Lebanese borders to the Lebanese Army; Hizbullah redeployed their forces close to Palmyra. The latest efforts of Hizbullah serve two purposes: 1) to release tension with Israel and hence avert an Israeli attack on Hizbullah inside Syria, and 2) to use its shrinking manpower more strategically to protect its supply line from Tehran.

Recent news coming from Syria was dominated by the American alliance strikes against a military convoy for the Shia militias approaching al-Tanaf crossing, which was captured recently by the American-led forces. Days later, and in a sign of resolve, the alliance forces air-dropped brochures that “advises” the Shia militias to refrain from further approaching opposition-controlled areas. Russia might have to negotiate with the Americans to secure a place on the borders for the Iranians, but that will come at a high price and only if the Russians succeed in interrupting the connection between the Kurds coming from the North and the Opposition groups advancing from the South.

Map No. (2) Battle of Eastern Homs and Al Sham Desert- 31 May 2017

Map No. (2) Battle of Eastern Homs and Al Sham Desert- 31 May 2017

This context shows that the de-escalation zone agreement was neither a Russian secret plan to divide Syria, nor a Russian trap for the U.S. and its allied groups. It actually reflects a pressing need for Russia to freeze the conflict for six to twelve months in the areas that have no strategic urgency, such as Ghota in the South, where Israel is concerned, or where in-fighting and Turkish influence will shape the situation in a less costly way compared to a direct intervention, like in Idlib. At this moment, Dir Ezzor is strategically more important than Idlib, and Nura is less of a threat compared to losing the borders with Iraq to the Americans.

Controlling the borders will change many equations for the regime and its allies: it will challenge its attempts to reclaim control over all of the Syrian territories; it will block the Iranian routes to Hizbullah; and it will give Americans the upper hand in both Syria and Iraq. Russians have tried to avoid confrontations with the Americans since their intervention in 2015, and such a scenario with American-proxy domination of the East and South might lead to undesirable tensions. More important, it is possible that at any moment the pressure of American proxies from the East and South on the regime areas will reverse the military vulnerability that Russia has successfully avoided in Syria so far. Consequentially, it is possible that Russia will be forced to accept a settlement that is not optimal to its interests.

The details of the agreement promise a successful implementation, but the absence of any follow-up or enforcement mechanisms make any euphoria disappear. There are sections of the agreement on international forces and monitoring mechanisms, guarantors, humanitarian access, refugees return, and reconstruction—all dependent on moderate forces restoring security and fighting terrorist groups. The possibility that moderates will be blamed for future acts of terrorists may cause rifts. The moderates will have to either essentially self-destruct by intensifying the in-fighting or face the threat of invasion or bombing by the Russians and the regime. The latest coalitions of HTS (al-Nusra coalition) will not be weakened or reversed before reaching a comprehensive political solution that could encourage small groups and individuals to defect and motivate the militia as an overall body to engage in a national Syrian military and political effort that meets its expectations.

Within the context, rather than the text, of the agreement, Turkey has agreed with Russia to deal with HTS in Idlib, an arduous task. Without a political settlement, Turkey will find itself facing increasingly disgruntled military groups that have the capacity to threaten the depth of the Turkey. There is little in the agreement that justifies the Turkish presence or its acceptance of the Iranian guarantees. However, given the Turkish sensitivities towards any expansion of the Syrian Democratic Forces, which is dominated by the YPG and its PKK connections, Turkish cooperation with Russia becomes less questionable. The Turks have an interest in depriving the Kurds from having a seat at the negotiating table to determine Syria’s future. Moreover, with current challenges in Turkish-American relations, any increase in U.S. presence in both Syria and Iraq potentially diminish the regional influence of Turkey. The Turks find themselves implicitly allying with the Russians and Iranians, against the Kurds and the Americans.

The US and the EU did not pay attention to the Astana conference from the beginning in order to avoid reducing the importance of Geneva to Russian-led talks and to comply with their Iran marginalization policy. Militarily, The Americans did not respond to Aleppo’s fall or Idlib’s suffer because there were considered out of their strategic influence zones. Alternatively, Americans invested heavily in the Kurds and the southern groups in cooperation with the UK and Jordan in order to capture ISIS-dominated areas in the East. That will not only increase the areas under their control but also will increase the US legitimacy as successful forces in fighting terrorism. The US hope that strategy will create a new situation that will force the regime and its allies to negotiate seriously, by American terms, in Geneva or otherwise. In the meanwhile, the Europeans did not break their silence on Astana either. The EU focuses only on Geneva and is suspicious of Russia’s efforts. The Russians failed to buy their support to Astana despite the incentives inserted in the agreement by promising the return of refugees and reconstruction.

Indetermination in the East, and slow fire in the West

Against the clarity of the parties’ plans, the realities on the ground might tell a different story. Looking more closely at the formation of the competing forces racing towards Raqqa and Dir Ezzor, it appears that they are neither professional nor disciplined nor coherent in their composition or end goals. That will likely result in a non-linear path towards domination, lasting a long time and resulting in a high number of civilian causalities. The Syrian Democratic Forces are perceived to be YPG-dominated, which may provoke an armed resistance by the Arabs of Raqqa, especially in cases of brutal conduct against civilians conducted by the YPG. That scenario will slow the SDF’s advancement towards the South and will force it to prematurely withdraw leaving a power and governance vacuum behind. The rest of the American-supported groups, such as Maghawer al-Thawra, the Lions of Sharkia, Shahid Ahmed Abdou Brigades, and Ahmed al-Garba forces in al-Hassaka, are no more disciplined and will bring the same problems.

The situation for the Assad regime and Hizbullah might look brighter, but threats of American air attacks and Russia’s decision to refrain from a direct confrontation will neutralize this advantage. The rest of the regime-aligned forces will include the nascent groups working under the Fifth Corps, such as the tribal forces, whose capabilities are still questionable. The Russians bet on filling the vacuum in Dir Ezzor after the failure of the American-led forces to establish control. That gamble indicates that the battle will not be settled any time soon and its outcome is uncertain.

The distraction from the western fronts does not exclude them from the spot light. HTS (al-Nusra coalition) will try to expand geographically and attract more groups and individuals to its coalition in order to weaken the moderates’ body. That might be countered if the newly formed Turkish-led forces succeed in uniting all moderates under the Euphrates Shield zone and advances into Idlib. Other interesting events include the race to contact and empower the LACs in Idlib and northern Aleppo as a humanitarian and development player in a future political transition or a stable ceasefire. Europeans and Americans have been a strategic partner of the LACs, and now also the Russians are looking for a place in Idlib and other de-escalation zones. All powers will seek to improve the capacity and legitimacy of the LACs, but competing over the political alignment of the LACs is counterproductive. The use of LACs as political tools for any party will undermine their role as professional service providers and as a popular medium between the government and the local population.

Recommendations for the opposition and international players:

1- The political opposition: Starkly, there were no Syrian signatories to the agreement, neither the government nor the opposition. This suggests that Syrians have lost control over the trajectory of the war in their own country. In Astana, the Syrians are observers rather than participants in any discussions concerning their cause, a position in Astana that disregards them no less than in Geneva. It is of interest to all parties, except for the Assad regime and Iran, to support the opposition in both conference. For that, there is a need to increase the capacity and legitimacy of the delegations. This can be achieved through:

- Uniting the delegations of both Astana and Geneva in consultation with the opposition allies. Merging the military weight of the Astana delegation with the regional and international recognition of the Geneva delegation will make one solid front in both venues. This will not happen without a show of will from the two delegations and without some pressure on the allies—specifically Turkey and Saudi Arabia. These efforts entail recalibrating the current political and military establishments of the opposition in order to accommodate such overdue restructuring.

- Increasing the technical capabilities of the delegation. Ever since Geneva I meetings in 2012, the opposition has needed to boost its capacity to conduct negotiations with the regime regarding myriad issues from humanitarian coordination to security reform, from reconstruction to the return of refugees. It is a mistake to assume that a constitution and elections will dominate the discussions. For example, the current de-escalation zones agreement includes minute details on the observers’ mechanisms and the international force composition and mandate, which are often out of the ream of expertise of unspecialized military officers. The failure to provide such capabilities will lead the delegation to blindly agree to unfavorable terms or unwittingly refuse to sign potentially favorable agreements.

- Increasing the legitimacy of the united delegation. Two dilemmas face the Syrian delegations in both Astana and Geneva: one is weak communication with their wider constituencies inside and outside of Syria; the other is the disconnect among local actors in the opposition-controlled area.

- Communicate with Syrians inside and outside of Syria. There is a need to improve the level and means of communication with Syrians in general, and especially those who count as natural constituency inside and outside of Syria. Direct messages 1) before negotiation rounds to explain the goals, 2) during the negotiations to elaborate on the development, and 3) after the end of rounds to summarize and hint on the future steps. It is possible to lose the message when there are too many delegations, each claiming to represent the Syrian cause.

- Communication with local elements in Syria. The more local support the more legitimacy is secured in the eyes of the international community. In Astana, the militias represent power brokers on the ground, but they still cannot speak for other elements like local councils. Geneva talks represent political elements and regional clout where more players on the ground are excluded. The political body of the opposition is responsible for securing the physical needs of its constituency and representing its demands. The failure to play that role casts doubt on its legitimacy.

2- The military opposition: The political opposition might look incompetent and unrepresentative to Syrians on the ground who have made significant sacrifices, but without the opposition it would be doubtful to receive political acknowledgement from the international community and hence weaken the possibility to transform the military achievements of Syrians on the ground into an institutionalized political gain. The military factions have hard tasks as they are responsible for defending their territories, as well as supporting the political process at once. The overall weight of the Syrian opposition does not give room for more than one delegation. Therefore, we recommend the following:

- Pressuring to unite the negotiations delegation. The political opposition needs the militias’ help to coordinate the efforts and to lobby the allies in order to support merging the two delegations.

- Providing a vision for the militias’ role in the transition period and the future Syria. Specific answers about the militias’ willingness and ability to professionally deliver security during the transition period, disarmament conditions, and integration in one united Syrian Army are much needed. Without clear and detailed answers to these questions, the negotiations process will be harder and all of the opposition’s sacrifices will be wasted. That eventually will transform the discontented fighter into a ticking time bomb in the future.

3- The Local Councils: The LACs are an important Syrian asset for future stabilization and should be preserved at any cost. Therefore, we suggest the following:

- Focus on professionalism in delivering services indiscriminately to all Syrians regardless of their faith, gender, and ideology.

- Boost the LACs legitimacy by observing the elections cycles and avoid any political or ideological aligning.

- Assure transparency in all transactions with donors to avoid any side deals with any harmful regional or international coalitions in the future.

4- The US and the EU: Both entities can enhance the substance of the current negotiations in Astana and Geneva, as well as facilitate the institutional transition through the following:

- Stepping up the US and the EU involvement in Astana on the political and technical level to assure better agreements in terms of implementation and following-up mechanisms. That would make it harder to be ignored and will reemphasize the US and EU’s responsible position towards the Syrian cause.

- Supporting efforts to unite the Syrian delegations, both financially and technically. It is worth noting the importance of building a Syrian expertise base instead of the unsustainable reliance on costly and unproductive western consultancy companies.

- Respect the professional and neutral aspects of the LACs and avoid pushing them into a polarized regional and international muddy field.

5- Russia: There is a big room for Russia to reach quick and more effective results in resolving the conflict, improving the substance and outcome of the ongoing negotiations in Astana and Geneva, and facilitating the institutional transition through the following:

- Avoiding undermining the legitimacy of the opposition and show goodwill by not targeting their local constituencies and deterring the regime and the Iranians from the same. A strong and legitimate opposition can uphold the agreements and assure their implementation, while a weakened one is a guarantee for instability and prolonged war.

- Facilitating access of humanitarian aid to the opposition areas to build trust with Syrian citizens and also to support the legitimacy of the opposition in their eyes.

- Establishing a communication protocol with the opposition delegation to Astana and Geneva in order to improve the substance and outcome of the negotiation rounds. The opposition delegation should obtain all necessary information that enables it to effectively represent its cause and transform the outcome into concrete results.

- Respect the popular representation nature of the LACs and support their role as a professional service and security provider. Avoid any miscommunication that would result in delegitimizing them in the eyes of their constituency or their main sponsors. Russia can be a positive force to bring stability into the opposition areas by securing an environment conducive to the return of refugees and the reconstruction of infrastructure.

- Cooperate with European countries and the US on supporting the LACS. This can be a good venue for trust-building and de-escalation between the US and Russia in Syria.