The Autonomous Administration: A Judicial Approach to Understanding the Model and Experience

As the central state authority declined, in favor of the emergence of sub-state formations including ethnic and religious ones, along with international and regional interventions, several local governance models have emerged across Syria as reflected by the dynamic military map. This led to the disappearance of some models and the decline of others, whereas other models achieved relative and cautious stability. In this regard, the “Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria” falls within the last category as it developed through several phases until it reached its current model. Although many years have passed since the actual declaration of the Autonomous Administration with its various institutions and bodies, the level of governance and nature of administration in these institutions and bodies remain problematic and questionable. Thus, this study seeks to explore the nature of the administration and the level of governance in this developing model using the judicial authority as an entry point, as it is considered one of the most prominent indicators. The impact of court processes is not limited to the judicial field, nor does it reflect the legal interest alone; it also offers several indicators on the political, administrative, security, economic, and social levels. Therefore, the study examines the judiciary system of the AA, its structure, various institutions, legal foundations, in addition to the employees working in and running those institutions and their qualifications. The study also attempts to explore the effectiveness, efficiency, and working mechanisms of this system, as well as its impact on North-Eastern Syria, in addition to the complex problems in that region (political, tribal, ethnic and “terrorism”).

Control and Influence Changes After Operation "Peace Spring"

This report examines, in numbers and charts, the developments in the northern region of Syria after the commencement of operation “Peace Spring" by the Turkish military and the Syrian National Army (SNA). The report highlights the following points:

- The current map of control and influence in northern Syria and other provinces that are geographically connected to the north;

- The map of the international and local actors in general, without detailing their influence or the extent of their control;

- Who is controlling the most important resources and infrastructure in the northern region (the most important international roads - International border crossings and their situation).

(Who's/What) controlling the Syrian north region

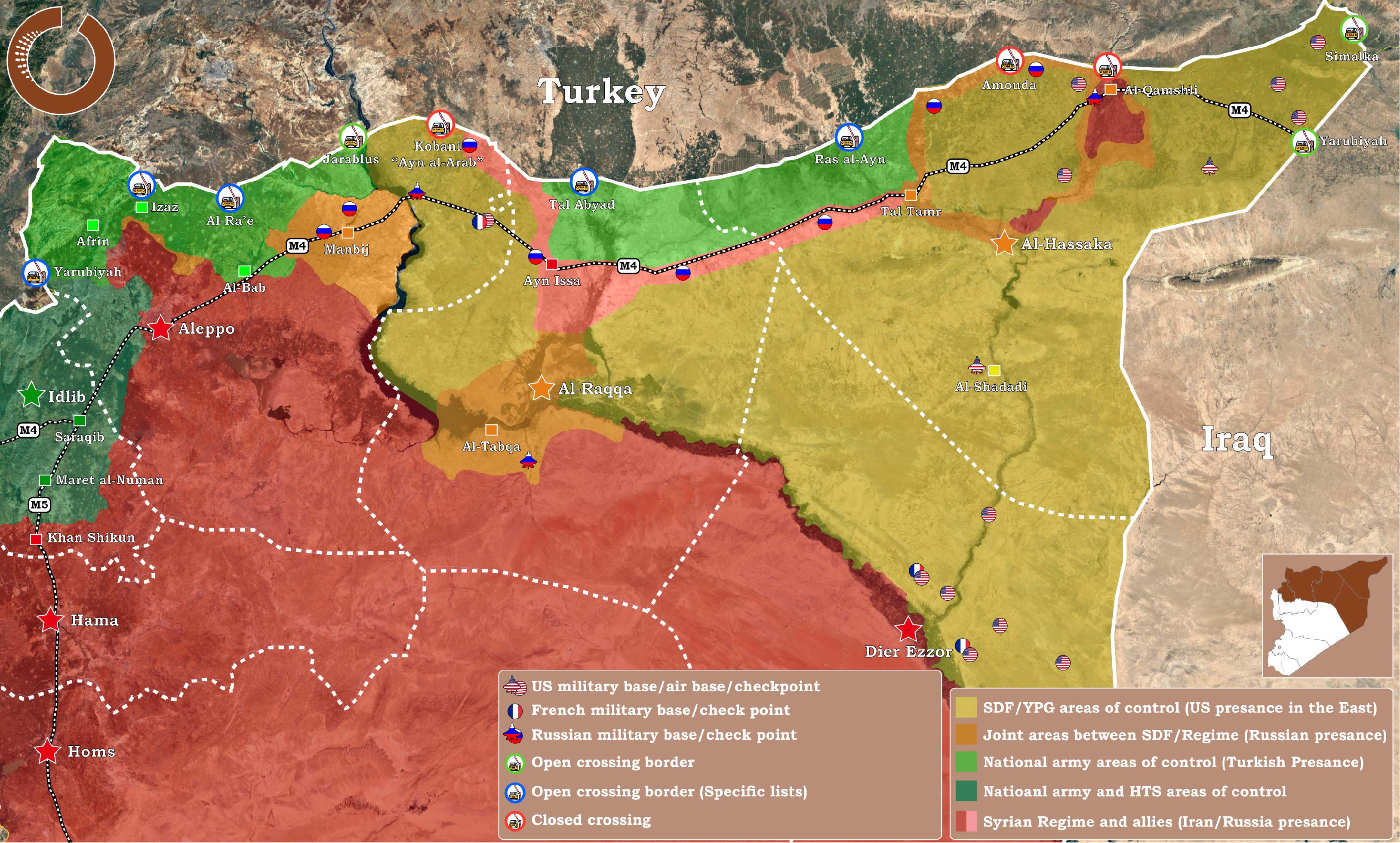

Map 1: Updated areas of control and influence in the Northern region of Syria – 12 December 2019

Map 1: Updated areas of control and influence in the Northern region of Syria – 12 December 2019

| USA | France | Russia | Iran | Turkey | |

| Al-Hassaka | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Al-Raqqa | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Aleppo | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Idlib | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table 1: International direct/indirect presence s in the Northern provinces in Syria – (General look)

| Province Area km2 | Regime Forces | Joint area (Regime & SDF) | SDF | Opposition Forces (SNA) | HTS | |

| Al-Hassaka | 23.334 km² | 4% | 5% | 83% | 8% | - |

| Al-Raqqa | 19.616 km² | 36% | 12% | 42% | 10% | - |

| Aleppo | 18.482 km² | 51% | 11% | 9% | 23% | 6% |

| Idlib | 6.097 km² | 22% | - | - | 33% | 45% |

Table 2: Local forces updated percentage of control in the north provinces in Syria

| M4 Length (Km) | Regime Forces | Joint area (Regime & SDF) | SDF | Opposition Forces (SNA) | HTS | |

| Al-Hassaka | 230 Km | 37% | 5% | 58% | - | - |

| Al-Raqqa | 103 Km | 76% | 24% | - | - | - |

| Aleppo | 195 Km | 22% | 30% | 20% | 17% | 11% |

| Idlib | 73 Km | 14% | - | - | 33% | 57% |

Table 3: Who's controlling M4 road from Iraq (Kurdistan) border to the administrative borders between Idlib and Hama provinces

| Province | Between | Local Forces | International Influence | Crossing situation | |

| Yarubiyah | Al-Hassaka | Syria-Kurdistan (Iraq) | SDF | USA | Open (Aid- US military) |

| Simalka | Al-Hassaka | Syria-Kurdistan (Iraq) | SDF | USA | Open (Aid-Civilians-US military- Journalist) |

| Al-Qamishli | Al-Hassaka | Syria-Turkey | Regime Forces | Russia | Closed |

| Amouda | Al-Hassaka | Syria-Turkey | Joint Presence (Regime/SDF) | Russia | Closed |

| Ras al-Ayn | Al-Hassaka | Syria-Turkey | SNA (Opposition) | Turkey | Open (Aid- TSK) ([1]) |

| Tall Abyad | Al-Raqqa | Syria-Turkey | SNA (Opposition) | Turkey | Open (Aid- TSK-Journalist) |

| Kobani | Aleppo | Syria-Turkey | Joint Presence (Regime/SDF) | Russia/Iran | Closed |

| Jarabulus | Aleppo | Syria-Turkey | SNA (Opposition) | Turkey | Open (Aid-Civilians- Journalist) |

| Al-Ra’e | Aleppo | Syria-Turkey | SNA (Opposition) | Turkey | Open (Aid-TSK) |

| Bab al-Salma | Aleppo | Syria-Turkey | SNA (Opposition) | Turkey | Open (Aid-Syrian Interim Government) |

| Hemame | Aleppo | Syria-Turkey | SNA (Opposition) | Turkey | Open (Aid) |

Table 4: Situation of the international crossing border in the Northern provinces in Syria

Transformations of the Syrian Military: The Challenge of Change and Restructuring

Executive Summary

- Throughout its history, the Syrian military has gone through a number of stages in its structural and functional evolution. These include processes undertaken based on the need to develop the military’s professional and technical capacity, or as required for the domination and control of the regime over the army, or as dictated by the war conditions. But since Hafez al-Assad took power, the military has become a major actor in local “conflicts,” whether as a result of the social composition of the military and the sectarian engineering efforts started by Hafez al-Assad and continued by Bashar al-Assad, the special privileges granted to military members, or as a result of the military doctrine that is customized for the preservation of the regime and not based on national ideals. Some of the most significant structural and human changes in the history of the Syrian military took place between 2011 and 2018. These shifts included the entry of auxiliary non-Syrian forces, both individuals and groups, which completely changed the role of the “army” from that of a traditional national army into a force used primarily to protect the ruling regime.

- As a result of the unexpected outbreak of military operations across the country against a popular uprising, there was a significant increase in the number of amendments made to laws governing the military establishment in order to address gaps in those laws. Some of the laws were ignored in favor of custom and tradition. This was reflected in the promotion and evaluation of officers based on sectarian or regional affiliations. The introduction of a partial mobilization in Syria without official certification of the decision as a result of the events starting in 2011, and the issuance of a new mobilization law at the end of 2011, supported the regime's efforts to distribute mobilization tasks to all state institutions and departments. Previously, the last law on mobilization had been issued in 2004.

- At the outset of the uprising in Syria, the military's deployments were characterized by complete chaos. The regime's use of local and foreign militias, in addition to the Iranian and Russian regimes, transformed this deployment from complete chaos to a more organized chaos. The regime was able to recapture many villages and cities based on a strategy of collective punishment, scorched earth offensives, and guerrilla warfare. The Syrian regime's use of local and foreign militias led to an imbalance in the structure and responsibilities of the army during the revolution, so that the military became a more Alawite-dominated institution because of its reliance on its Alawite members. Most of the officers were corrupt, and that corruption became much worse during the years of revolution, causing the military to become increasingly distant and isolated from society. This pushed the officers to collude with corrupt networks within the regime and to exploit them to achieve further gains and accumulate wealth.

- In 2018, the military landscape witnessed many major transformations, most notably the division of the country into three main international spheres of influence, each of which contained a diverse mix of local political powers. In the first sphere controlled by the regime, there were indicators of increased Iranian and Russian influence, as well as an attempt to consolidate the militia scene, with some being dissolved and others linked to Iran being integrated and merged with others. In the second sphere: includes the armed opposition forces in northern Syria backed by Ankara, the map of relevant armed actors became more disciplined and contained under the framework of the Astana talks. Opposition forces displaced from southern and central Syria were restructured by Ankara in support of the Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch operations. In the third sphere: the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) continued to perform their security and military functions under the self-administration project and its legal framework. At the same time, their negotiations with the Assad regime continued, leaving their options wide open and making it more likely that the situation would get more complicated because of the lack of a clear policy from the Americans who supported the SDF on the one hand and pushed for further negotiations on the other.

- The regime’s attempts to reduce and contain the roles carried out by Iranian and local militias were not comprehensive or well organized. On one hand, many Iran-backed militias became integrated into the official regime military structure following the formalization of Iranian operations in Syria, which did not reduce or contain its power or impact. On the other hand, the overall reintegration strategy was not adhered to especially with regards to local militias or groups that settled through reconciliation agreements, as the objective of conducting operations against opposition forces is still prevalent and dominating deployments. This process of reintegration will face further obstacles that will greatly hinder any restructuring process as a result of the deep infiltration of such militias and the diverse roles they play in society and within the security sector.

- The data and indicators examined by the papers contained in this book highlight the deep and significant impact of transformations in the military institution both in the medium and long terms. These transformations are observed in the structural and functional imbalances of the military institution especially as it faces a deficit of power, capacity, and resources. Furthermore, the regime’s military institution has become one of many other actors in the scene and often held hostage to local and international networks of power, whether it is the Russian or Iranian or other local groups. It is also restricted in its capacity because its imbalanced societal composition, has not adopted political neutrality, and the ideological party doctrine that dominates. All this necessitates a rebuilding strategy that is absent from the current regime’s agenda as well as its allies in favor for superficial rehabilitation for the purpose of regaining control of territory and society.

- In the face of the current frame of reference that guide the reform course of the military institution, the absence of a national agenda or vision should be noted. This vision should stipulate the requirements for the reform process, most important of which is the political process and change, depoliticizing the military institution, protecting political life from military interferences, and the reinforcement of healthy and normal civil-military relations that enhance its performance.

Introduction

Based upon the need to redefine the roles of the Syrian military institution in light of the profound transformations in the concept of nation-state, Omran Center for Strategic Studies launched this research project to further analyze those transformation and address the challenge of change and restructuring. The approach first deconstructs and assesses the functions and structures of the Syrian army, its doctrine, and causes behind its involvement and interference in social and political affairs in accordance with the regime’s philosophical vision of domination and totalitarian control. The papers contributed by researchers in the first phase of this project are as follows:

- The Syrian Army 2011-2018: Roles and Functions

- Military Actors and Structures in Syria in 2018

- Stability and Change: The Future of the Military in Syria

- Annex Report 1: Significant Transformations in the Army: 1945-2011

- Annex Report 2: Laws and Regulations Governing the Military After 2011.

The outputs of papers and reports in this book assess indicators of instability in the map of military actors and measure its impact on the centrality of defense and security functions and the future end game for the nodes of power within the military after possible reintegration processes. It also focuses on the relationship between the military and political spheres, in the sense that it evaluates the potential for military actors to contribute to various avenues of reform, including the redistribution of power in a legally decentralized manner. Similarly, it also looks at the changing political situation and the positions taken by regional and international backers of armed groups, which influence the decisions of military actors, leaving them with limited options.

This book first outlines the main historical developments in the Syrian military in order to establish a more comprehensive understanding of the shortfalls in the military structures and how they developed. It also looks at the most important laws and amendments related to the military establishment and how they have evolved over time. The book also describes how the military leadership used these laws after the start of the Syrian revolution to recruit fighters to the military that were completely loyal to the ruling regime.

The papers and reports in this book try to answer a number of key questions such as: does the military in its current state embody features of effectiveness, adopt a national outlook, have the capacity and ability required to preserve and promote the outputs of a political process, and able to create and promote conditions for stability? Addressing these questions necessitated first to recognize the positioning of reform policies within the current and future military institution agenda, and to assess the presence or lack of a cohesive and stable structure after the profound transformations it witnessed. Finally, the book outlines an initial vision for a framework for reform that would allow this institution to be a catalyst for societal cohesion and adopt a politically neutral position to become a source of stabilization is Syria.

Omran Center plans to launch a second phase with additional papers to be based on the outcomes of papers contained in this book as well as discussion and feedback received from participants in the workshop held in Istanbul on October 25th, 2018 to focus potentially on the following topics:

- Sectarianization mechanisms in the Syrian military.

- Power nodes and networks in the Syrian military.

- Management of surplus manpower: a case study of the 4th and 5th corps.

- The military judicial system.

- Non-technical challenges in the reform of the military establishment.

For More Click here

Centralization and Decentralization in Syria: Concepts and Practices

Introduction

After seven years of conflict between the people and the Assad regime, Syria is now going through a difficult phase. The nature of the conflict has transformed whereby the role and effectiveness of local actors has been greatly maringalized compared to an increasing role for international state and non-state actors. The role of armed opposition factions has diminished as international military, administrative, and political influence has grown. These armed opposition actors are also in a phase of turmoil as they struggle to survive or integrate under direct international custodianship, after having previously received support from the Northern or Southern Operations Rooms. This process follows the series of meetings in Astana and Sochi, and after the political bodies were domesticated into official negotiating bodies that support the interests of countries with direct influence over them. At the same time, direct Russian influence came to dominate the political, military, economic, and administrative spheres. As a result, the concept of the unified framework of the "regime platform" versus the "opposition platform" in accordance with the Geneva II concept was discarded through the creation of several negotiating platforms on the sides of the opposition, the regime, and the Syria Democratic Forces (SDF).

At the same time as these political changes were happening, the areas of influence and control on the ground were consolidated in 2018 into the north and northwestern portion under Turkish control, the northeast under the U.S. and SDF control, and southwestern Syria under the influence of the U.S. and Jordan, allowing Israel to strike any sites that it deems threatening. The areas of siege and opposition group control have been eliminated. International and regional influence has thus become more distinct, as efforts to control and integrate both armed opposition and pro-government groups continue.

This new phase is characterized by a complex series of partial deals that build on one another, and the arrangements among the state actors are developing in a "step by step" policy approach. The "counter-terrorism" framework that was used to justify the entry of these countries into Syria, is no longer a justification for their continued presence and influence: the U.S. is increasingly focused on the "Iranian threat;" Turkey is focused on "fighting the PKK" and security its borders; Israel justifies its interventions with the need to protect its borders against the "Iranian threat" and to prevent the transfer of weapons and fighters toward its borders; and Jordan is now also interested in protecting itself against the “Shi’ite crescent".

In light of this new landscape, contributing writers to this book discuss several aspects of Syria's current form of governance and how experiences on the ground in the different areas of influence converge or diverge from the concepts of centralization and decentralization, both vertically and horizontally. Towards this end, the chapters of this book first clarify the concepts and forms of decentralization and the way they are applied in post-conflict countries. They highlight the important role that agreeing on the form of governance and power sharing is an important factor in maintaining territorial unity and in shepherding negotiations to a more relevant stage of the new post-conflict reality. Next, the authors delineate decentralization in terms of its political, security, financial, and developmental functions, and review the constitutional and legal foundations of administrative and political decentralization in Syria. Finally, the authors present the experiences and applications of governance since 2011 in the regime-controlled areas and opposition-controlled areas, as well as in the SDF-controlled in northeast areas of the Democratic Autonomous Administration. Woven throughout the book are comparative descriptions of the experiences from Iraq, Lebanon, and other countries emerging from conflict, to see what lessons can be learned from the ways that these countries have negotiated the distribution of powers between central and local administrative units.

This book aims to help lay out a path towards the restoration of the legitimacy lost by all parties in Syria through the organization of local governance tools based on the experience of local councils. Local councils have tended neither towards excessive forms of decentralization nor to authoritarian centralization, but have instead followed a path that strengthens local structures and sets limits to central state authorities by granting powers rather than delegating them. At this stage, it is essential to work in parallel on strengthening the central government while also safeguarding and reinforcing the gains of the local councils through constitutional guarantees and a new local governance law. This book also stems from recognition of the need to shift away from limited centralized negotiations among the two “sides of the conflict” through a constitutional process followed by general elections, towards a negotiation based on power-sharing arrangements. Local governing bodies and other local actors should be engaged in the process of deciding which functions and authorities are mandated to the central institution versus the local governing units.

The chapters of this book were contributed by several researchers who differ in their approaches, but they all agree on the need to develop a decentralized Syrian model that avoids the reductive binary approach of political decentralization / administrative decentralization or federalism, and one that is based on the sharing of powers and functions, thus transitioning Syria’s system of governance from local administration to local governance. There is no doubt that further development and discussion of these ideas is required, but we present this effort as a starting place for a dialogue in the Syrian community on the most authentic or locally developed form of governance for Syria, which after years of adhoc decentralization, has become more localized than ever before.

Finally, it is important to note that most chapters were written in late 2017 and early 2018, which was before the change of control of Damascus suburb, northern Homs and the southern front. The arguments for a tailored and customized Syria-centric decentralization model put forth are still valid regardless of the controlling armed party.

Executive Summary

Chapter one of the book focuses on the concept of decentralization and illustrates the differences among countries when it comes to choosing how they exercise administrative authority. Every country’s approach to governance is influenced by its political and social conditions, as well as the maturity and depth of its democratic practices. The need to shift towards a decentralized system becomes apparent after examining factors related to a state’s nature, size, and degree of political stability. Decentralization becomes a necessity for stability in some countries because of its core idea: the distribution of power and functions of state institutions between the central governments and local administrative units. This conceptualization reaffirms the fact that the transformation to fully decentralized system may be risky for many governments, despite the promise that decentralization holds as the solution for most conflicts in developing countries such as those in the Arab world. Chief among these problems is the need to expand the political and economic participation of citizens. Still, given the ethnic and sectarian diversity and complex nature of countries, decentralization can be a threat to state unity.

Chapter two describes political functions of the state in a decentralized system and how it is practiced in different versions of decentralization. Political functions of the state take many forms depending on the degree of decentralization and mode of local governance. The far end of a decentralized governance system continuum appears in the practice of full political decentralization (full federalism), where provinces and regions have their individual constitutions and laws, exercise special legislative, executive, and judicial powers, and influence federal government policy through a political oversight authority and through their representatives in the legislative branch councils. Local governments, meanwhile, exercise specific roles in these functions under the partial political decentralization within their constitutionally-vested authority. These roles are primarily related to domestic policy-making and the development of local rules and regulations that do not contradict federal legislations. In administrative decentralization modes of governance, the practice of political functions and duties is reduced to a great extent as it focusses exclusively on administrative and executive functions of local governing institutions. Local administrative units would then be fully subordinated and controlled by the central administration in the capital. In partial administrative decentralization modes of local governance, political functions completely disappear from local units.

According to chapter three of this book, the exercise of legislative and judicial functions within a decentralized system will require reforms in the Syrian judicial branch, such as: the restructuring of the Supreme Judicial Council to ban the executive branch from holding membership in it and stop its interference, and the repeal of laws that encroach on public rights and freedoms with judicial not executive branch oversight. Assessing the current form and content of the Syrian Constitution in terms of centralized or decentralized approaches highlights centralism as highly visible and grants authority to the presidency (which has broad constitutional powers) to override all other authorities and functions of the state. Instead, the principles of separation and distribution of powers should be applied to three independent bodies in order to create balance and cooperation between them. With regard to legislative duties in Syria, this paper shows that the Constitution has broadly granted legislative duties to the People's Council of Syria (Parliament) and the President of the Republic, transforming the mandate of the Parliament from drafting laws to ratification of presidential laws. Reforming this imbalanced structure requires redefining the scope and mandate of the Parliament, abolishing the broad powers granted to the President, and reducing the centrality of legislation process and parliament. There needs to be a shift toward some kind of decentralization that divides future legislative functions in a balanced approach between the exclusive jurisdiction of the legislative branch, and the jurisdiction of the executive branch for all that is not stated in text of the constitution.

The fourth chapter focuses on security functions in decentralized systems. In the context of conflict-ridden or post-conflict countries, it is critical and necessary to re-assess national security functions: their applications, mechanisms for implementation and governance, and how security roles are distributed at different levels of government. This paper emphasizes that the redistribution of security duties and authorities in decentralized countries (in accordance with the lessons from stable and unstable countries) may result in a more efficient and coherent security architecture depending on who and how such a process is executed and whether by means of national actors, cross boarder actors, or international actors. In the search for a governing framework of the Syrian security sector within a decentralized system, independent intelligence agencies should have a clear mandate of intelligence gathering only (except for police forces and anti terrorism units that can arrest citizens) and an identified geographical jurisdiction. Local governing bodies should be constitutionally mandated to provide local security services and conduct police functions and duties locally. The assessment and identification of security threats and risks and the counter strategy to such risks should be developed locally and shared with central agencies for coordination.

The fifth chapter highlights the dialectical relationship between decentralization and its role in local development in countries emerging from conflict. Local development is one of the most important determining factors in whether or not decentralization is adopted in these cases. While some of post-conflict countries have reached acceptable rates of economic and social development after moving to a decentralized system, others have not. This disparity may be due to factors linked to each country’s particular local development process and adopted form of decentralization. This paper emphasizes that in the context of the Syrian situation, the country has suffered from the absence of a clear developmental model for decades. This has led to major developmental imbalances at the central state level, which are most evident in the developmental disparities between Syrian governorates. The adoption of a model of administrative decentralization in Syria will help to mitigate this disparity by empower local communities to participate in the local development process.

The sixth chapter, which deals with financial decentralization, emphasizes the fact that the successful implementation of decentralized systems of government in post-conflict countries depends largely on their ability to establish regulatory frameworks for financial decentralization and mechanisms for the collection, distribution, and disbursement of financial resources at various levels of government and administration. Successful implementation also requires substantial reforms in fiscal policy in general and in spending policies in particular. This paper finds that that the model for allocating financial resources to the local administrative units out of the state budget in Syria has many flaws. It is necessary to grant administrative units greater financial independence and to define metrics for successful financial decentralization to measure whether these units are meeting developmental requirements and making effective contributions to economic and social stability in their regions.

The seventh chapter examines the reality of local administration in regime-controlled areas. It illustrates the dominance of the central government in the local administration systems in regime-controlled areas, the growing influence of the Baath party, and the increasing influence of local Iran-backed forces in the operations of some local administrative units. This paper finds that the service sector crises in the areas of local administration units are indicative of their lack of funding, dysfunctional mechanisms, and insufficient personnel, forcing them to rely on the central government to conduct their affairs. It also argues that the regime is not interested in decentralization – which runs counter to its desire to retain centralized control – but it does use decentralization politically as a bargaining chip for negotiations with the international community, particularly the Europeans. The regime also attempted to manipulate the boundaries of the electoral constituency of administrative units to change administrative districts and weaken opposition areas by preventing them from winning elections in their areas while rewarding loyalists.

The eighth chapter focuses on the reality of governance in Syrian opposition-controlled areas. It reaches several conclusions, the most important of which is that local councils have undergone changes in terms of structure, mechanisms of formation, and function, as their organizational structures have stabilized and they rely increasingly on the elections for their membership. They have also been able to consolidate their service roles, compared to their role in local security and politics. The financial file is one of the primary challenges facing local councils as they cope with growing financial deficits, due both to the nature of revenues and expenditures, and also their lack of financial systems or laws regulating their budgets. This chapter explains how the long duration of the conflict, the transformations in its nature, the push towards coexistence, and the survival of the regime have all stimulated competition between local actors, of which the local councils were one of the most prominent players due to their political value and local legitimacy. As a result of the way the local councils have dealt with these challenges and threats, they face one of three scenarios in the foreseeable future: vanishing entirely, forming regional or cross-regional self-administrations, or continuing the current independent local units structures.

The ninth chapter analyzes the reality of governance in the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. It shows that lack of transparency is a key feature of service delivery, financial administration, and the management of strategic resources within the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. The process of forming legislative councils (mandated to pass laws) in these areas was based on partisan consensus that relied primarily on the literature and system of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM). Laws passed by these legislative councils, such as laws related to self-defense, changes to school curricula, and civil status laws, are problematic. A review of the structure of the DAA and its legislative and executive bodies, shows the presence of a partisan political project that is being forced on the local population through its security and military apparatuses. This paper concludes that the DAA, though able to impose a unique governance model, still suffers from problems of representation, legitimacy within its population, and a lack of competent personnel, and it has failed to eliminate the local and regional concerns arising from this project.

The tenth and final chapter of this book proposes a unique Syria-customized decentralized framework, one that takes into account the importance of achieving stability. It highlights the importance of refocusing international negotiations on two parallel tracks: negotiations policies to strengthen central state institutions in order to create conditions for peace and stability, and empowering local governance models through local negotiations on power sharing of authorities and functions of the central state with local administrative units. They must also revisit the basic Geneva Communiqué according to the principle of power sharing agreements between the center and periphery and not only a central agreement where the opposition and regime share authority. This means prioritizing internationally-monitored elections over any other track, beginning with local administration elections.

In order to ensure the success of the elections, essential actions are required from the different parties with regards to the restoration of the functionality of police and local courts. It is therefore necessary to begin drafting a new law for local administration (decentralization) to allow locally-elected authorities to have full control over the work of the police and administration of local courts.

The opportunity exists for local councils to legitimize their structures and negotiate new authorities, guaranteeing a decentralized model that provides expanded authorities to the councils and governorates, based on the strength of their electoral legitimacy. This chapter emphasizes the need to empower the tools and foundations of local governance both constitutionally and legally, and to ensure that the countries with a presence on Syrian soil help push the negotiations to a peace-building stage and guarantee relative stability on the ground until an agreement on the various security arrangements is concluded.

for More Click Here: http://bit.ly/2B2Vxqd

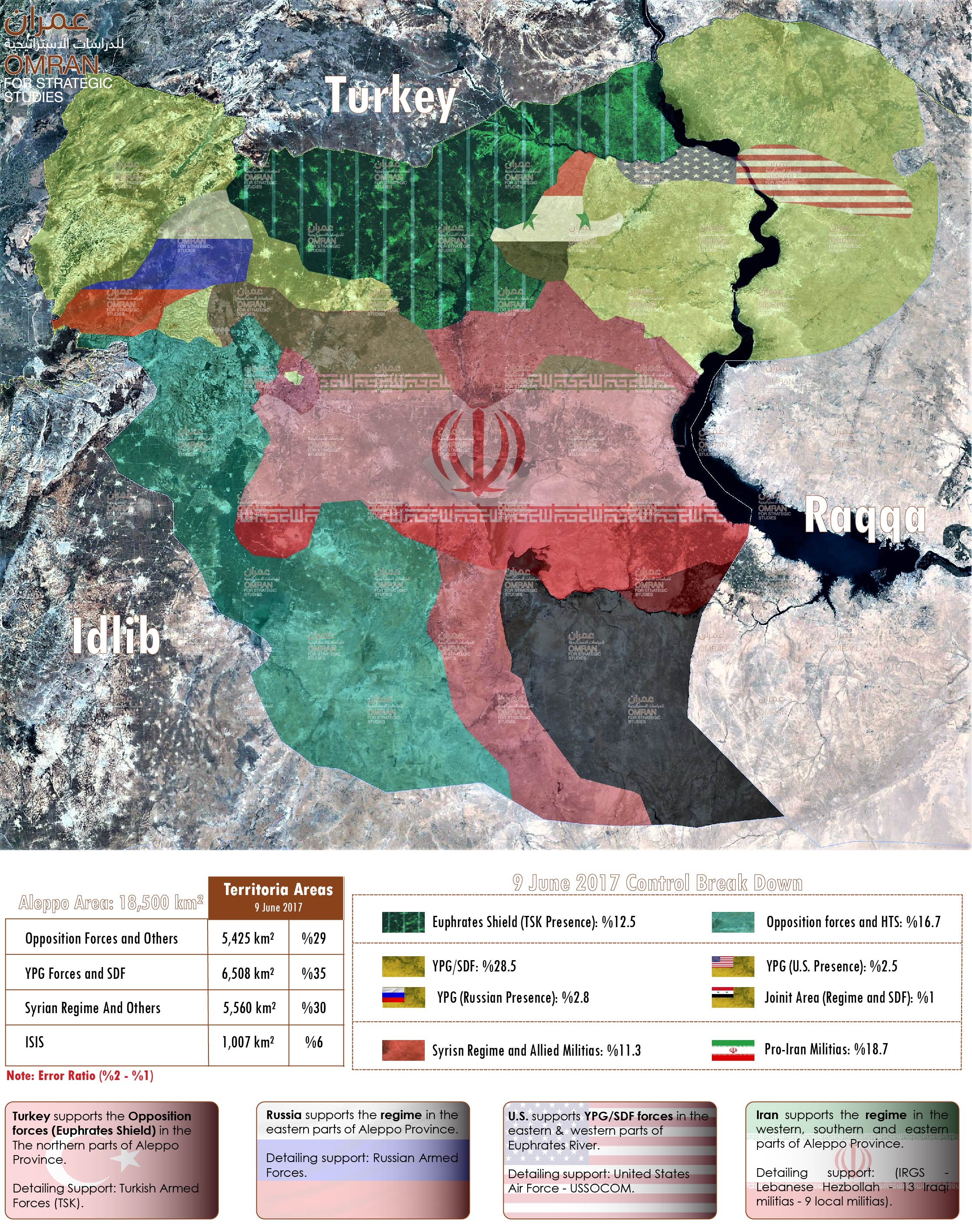

Map of Control and Influence: Aleppo Province "9 June 2017"

Battle of Deir ez-Zor & Raqqah September & October 2017

- October 9, Syrian Democratic Forces reportedly continued their advance in the eastern Deir-Ez-Zor governorate, capturing Mweileh town in Sur subdistrict, located north of Sur city.

- October 10, Syrian Regime offensive is largely dependent on Russian aerial coverage; the Russian Foreign Ministry announced that 150 daily Russian airstrikes had targeted ISIS bases in Mayadin city.

- October 15, SDF spokesperson announced that all willing combatants have evacuated the city; however, the likely destination of potential ISIS-affiliated evacuees is currently unknown. Furthermore, the SDF-led ‘Wrath of Euphrates’ operation against ISIS has led to SDF control over most neighborhoods in Ar-Raqqa city amidst heavy aerial support by the U.S.-led coalition, resulting in a high rate of civilian displacement.

- October 15, Syrian Regime forces and Allied Militias, supported by Russian aerial and ground forces, continued their advance south of Deir-Ez-Zor city, Syrian Regime forces, advanced into Al Mayadin city, Al Mayadin subdistrict, located 43.8 km south of Deir-Ez-Zor city.

- October 17, About 400 Islamic State (ISIS) members, including foreign fighters, have in recent weeks surrendered to U.S. backed forces in ISIS former Syrian stronghold Raqqa; inside source confirmed that the ISIS Syrian fighters were transferred to "Ayn Issa" Camp, while the foreign fighters were transferred to "Suluk" Military headquarter.

- October 18, Syrian Democratic Forces reportedly captured the several villages from ISIS, 7 KM eastern side of Deir-Ez-Zor City.

Important Note: As of the end of September, nearly 708,000 individuals are reported to still remain in ISIS-held communities in Deir-Ez-Zor governorate. This includes approximately 120,000 individuals in ISIS-held northern Deir-Ez-Zor governorate between Tabni, Tabni subdistrict, Deir-Ez-Zor City and the Euphrates River; 68,000 individuals in the ISIS-controlled western Deir-Ez-Zor governorate from Khasham in Khasham subdistrict to Markada across Khabour River; 120,000 in southern Deir-Ez-Zor governorate from Hajin to Abukamal; and nearly 400,000 individuals in the central Deir-Ez-Zor governorate.

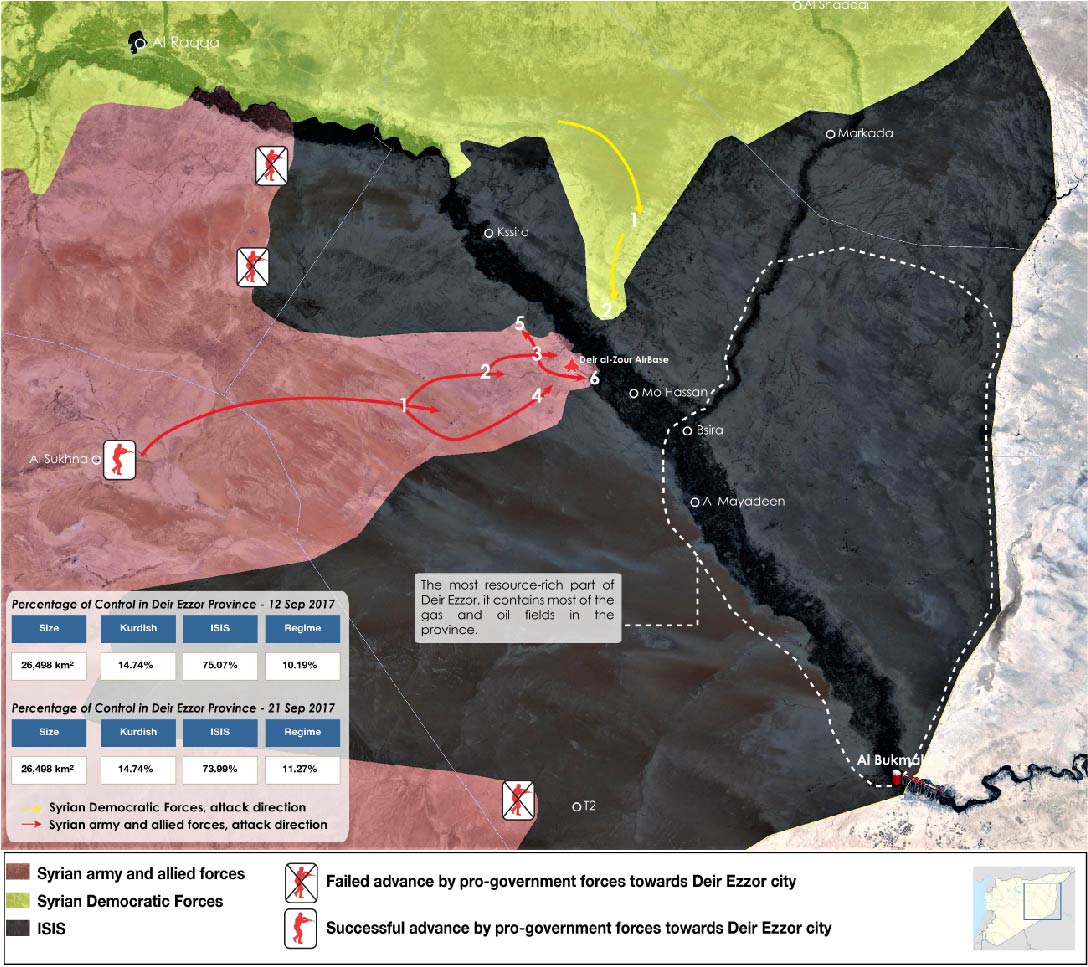

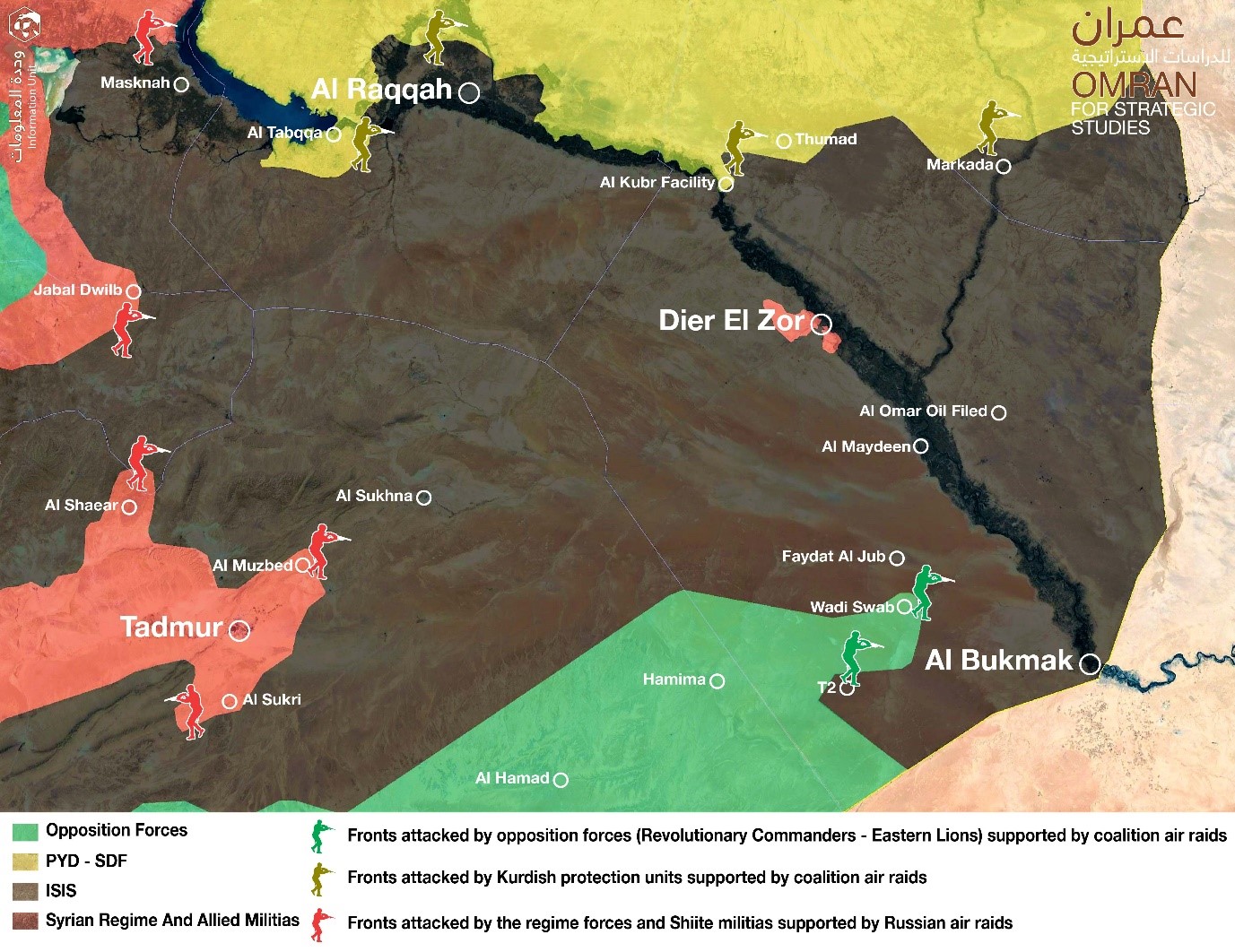

Mapping the Battle Against ISIS in Deir Ezzor

In recent weeks, the so-called Islamic State has suffered a string of defeats in eastern Syria. It has lost swaths of territory in Deir Ezzor city to advancing pro-Syrian government forces and has been driven from villages and oil fields on the eastern banks of the Euphrates River by a U.S.-backed paramilitary group.

The two simultaneous but separate offensives by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and Syrian government loyalists may have resulted in quick gains in their first few weeks, but fighting is ongoing in many parts of the province, much of which remains under complete militant control.

ISIS still controls roughly 74 percent of the Deir Ezzor province and commands two main strongholds in the areas of Boukamal and Mayadin, south of the provincial capital. The group also controls a resource-rich region east of the Euphrates River that contains most of the oil and gas fields in the province.

With a long and grueling campaign still underway to expel the militant group from its last bastion in Syria, Syria Deeply examines the battle for Deir Ezzor by looking at the main groups, their objectives and their advances in the region.

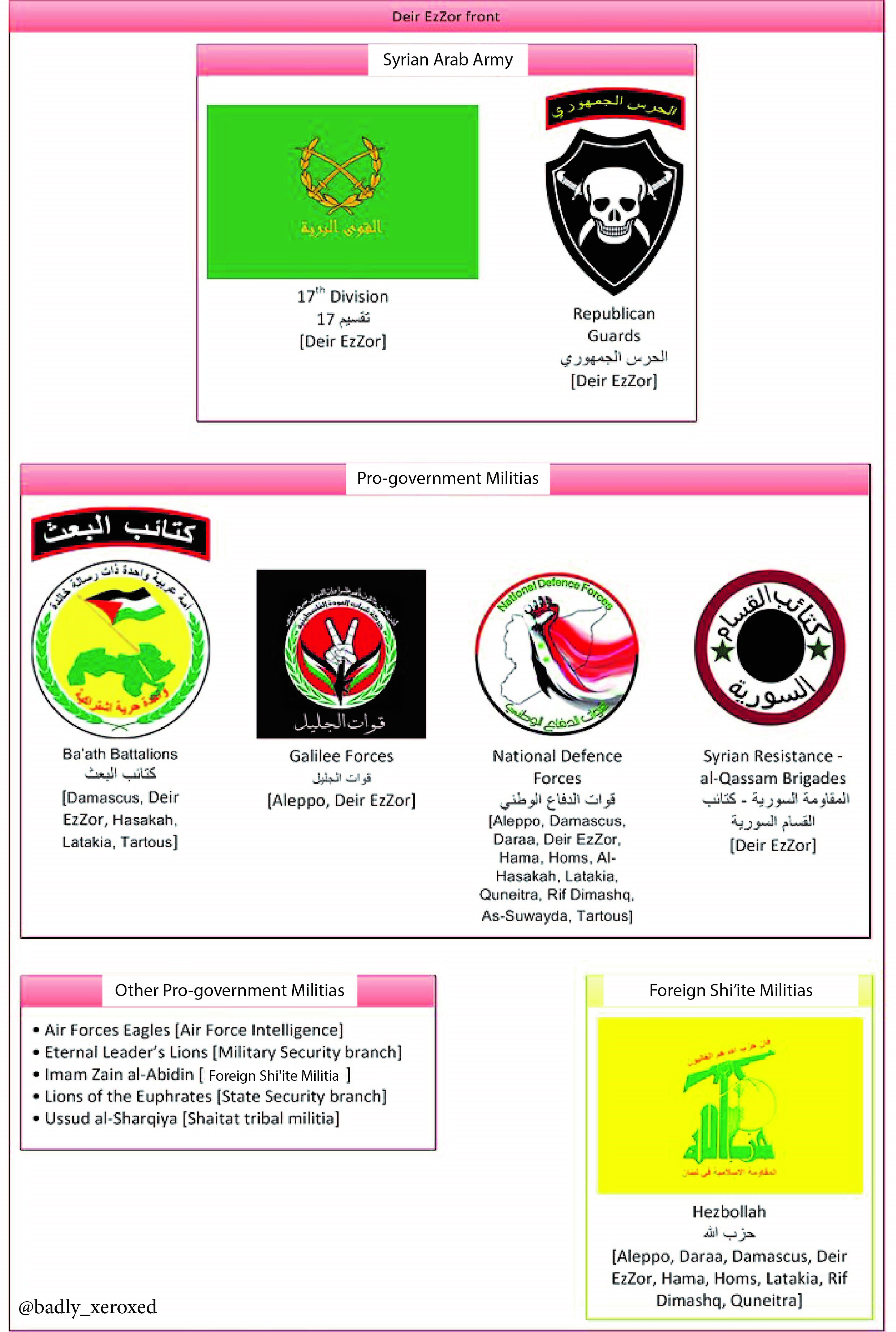

Who Is Fighting in Deir Ezzor

Syrian government loyalists are the main fighting force in Deir Ezzor city and the surrounding countryside. Their forces consist of two specialized Syrian army divisions: the Republican Guard and the 17th Reserve Division, which is responsible for northern and eastern Syria.

A number of pro-government militias are assisting, including the Baath Battalions, a Syrian paramilitary group that fought rebels in Aleppo province last year. The Galilee Forces (a Palestinian militia), the National Defense Forces(one of the largest pro-government militias operating in Syria), and the Syrian al-Qassam group’s elite forces.

The Lebanese Hezbollah and a number of other Iran-backed groups are also fighting alongside the Syrian army in Deir Ezzor, as are a number of local tribes, most notably the al-Shaitat tribe. Russian warplanes are providing aerial cover for pro-government advances, and Moscow announced on Thursday that it has deployed special forces to assist the Syrian army.

Infographic breaking down the multiple groups fighting alongside the Syrian army in Deir Ezzor. (Nawar Oliver)

On the eastern banks of the Euphrates River, a contingent of the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces, known as the Deir Ezzor military council, is also fighting ISIS. It is supported by U.S.-led coalition warplanes and U.S. special forces embedded within its ranks. The Deir Ezzor military council is made up mostly of Arab fighters from Deir Ezzor, but is supported by Kurdish fighters of the SDF.

The Race for Deir Ezzor

Although the SDF and the Syrian government have framed their respective operations in Deir Ezzor as primarily a battle against ISIS, each side has other objectives.

For the Syrian government, recapturing Deir Ezzor has been a main priority since the start of 2017, and gaining complete control over Deir Ezzor city, the largest city in eastern Syria, would be a symbolic victory.

Control over the oil-rich region on the southeastern flanks of Deir Ezzor province would also secure key natural resource revenues for the Syrian government.

The province is located along part of Syria’s border with Iraq, so controlling the area would help the government reassert its authority over the quasi-totality of its frontier with its southeastern neighbor. Increased government influence in Deir Ezzor would also help Iran secure a land bridge between Iraq and Syria, especially via the city of Mayadin, which provides a land route from Damascus to Iraq.

The government’s push in Deir Ezzor is also aimed at preventing a Raqqa scenario. In other words, the Syrian government is trying to keep U.S.-backed forces in Syria from carving out a zone of influence in the eastern province after ISIS withdraws.

For the SDF and its primary backer, Washington, the battle for Deir Ezzor is largely posturing against Assad’s forces. The group announced its operation in Deir Ezzor only days after pro-government forces breached ISIS’ siege on parts of the city, signaling to the government that its advance in the province would not go uncontested.

Although the SDF has said it would not enter Deir Ezzor city and would leave the area to pro-government forces, the group is seeking to expand its influence in the oil-rich parts of the province on the eastern banks of the Euphrates and in ISIS strongholds near the border with Iraq. This push is driven by Washington’s aim to secure the Iraqi border and prevent Iran from gaining a foothold in the region.

Tracing Government Advances

In recent weeks, pro-government forces have pushed into Deir Ezzor city from the west, along the al-Sukhna-Deir Ezzor highway, and achieved significant territorial victories in the provincial capital and its countryside. They have pushed ISIS militants back from areas around a military garrison known as Brigade 137, have breached a three-year siege of Deir Ezzor’s military airbase and a number of adjacent neighborhoods, and have also secured the strategic Deir Ezzor-Damascus highway.

Map of control for Deir Ezzor province that also shows advances by pro-government forces and the SDF. (Nawar Oliver)

The Syrian army said over the weekend that its forces have captured at least 44 villages and towns since launching the assault on Deir Ezzor earlier this month. According to the Syria Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), pro-government forces control roughly 64.3 percent of the provincial capital, while ISIS militants control 35.7 percent. Russia’s Defense Ministry, however, said last week that pro-government forces are in control of at least 85 percent.

They have also made significant gains on the western banks of the Euphrates, in Deir Ezzor’s northwestern countryside, where they have captured more than 60 miles (100km) of former ISIS territory, the SOHR said last week.

Pro-government forces also crossed into the eastern bank of the Euphrates last week, reaching within 3 miles (5km) of SDF-held positions.

The government’s advance suggests three short-term objectives. By expanding control on the western and eastern banks of the Euphrates, the Syrian government is trying to seal the eastern and western gateways to the city, thereby besieging ISIS in a pocket in the provincial capital.

It is also trying to complicate SDF advances in the region by preventing the group from reaching ISIS positions on the western axis while also blocking any potential SDF push down the east bank of the Euphrates.

The advance on the eastern banks of the Euphrates is also driven by an attempt to secure oil and gas fields in the area, most notably the al-Omar oil field, Syria’s largest and most lucrative field.

Current advances, however, do not signal an imminent push south toward ISIS strongholds in Boukamal and Mayadin. It would appear then that the real battle in ISIS’ best-fortified stronghold is delayed.

Tracing SDF Advances

Over the past two weeks, the SDF has pushed into Deir Ezzor province from the northeast using the Hassakeh-Deir Ezzor Highway, gaining full control of Deir Ezzor’s industrial zone and capturing a major gas field in the area.

The Conoco gas plant, Syria’s largest, came under full SDF control on Saturday, after days of fighting ISIS militants in the area. The plant had the largest capacity of any in Syria prior to the conflict, producing up to 459 million cubic feet (13 million cubic meters) of natural gas a day.

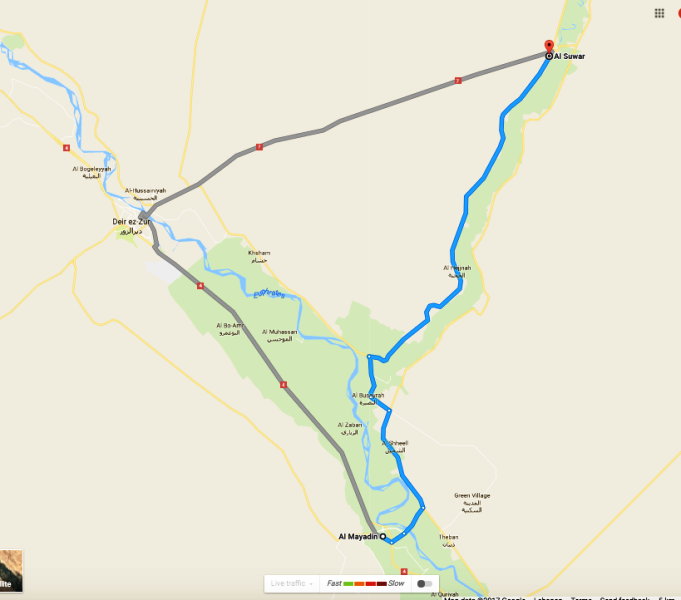

SDF forces are now moving away from Deir Ezzor city and advancing toward the Iraqi border. On Sunday, the push to capture the town of al-Suwar began, according to the SOHR. The area is a strategic junction which provides land and supply routes connecting SDF positions to ISIS strongholds in Boukamal and Mayadin. A coalition spokesman said over the weekend that these two ISIS strongholds, some 50 miles (80km) west of the Iraqi border, are the SDF’s eventual goal.

Risk of Confrontation

The race for gas and oil fields in the eastern banks of the Euphrates has increased tensions between Russia, the U.S. and their respective allies over resource-rich parts of Deir Ezzor.

The SDF said on Monday that Russian warplanes bombed their positions in the Conoco gas field, killing one SDF fighter and wounding two others, just two days after the U.S.-backed forces captured the area.

That same day Moscow blamed U.S. policy in Syria for the death of Russian Lt. Gen. Valery Asapov in ISIS shelling near Deir Ezzor one day earlier.

“The death of the Russian commander is the price, the bloody price, for two-faced American policy in Syria,” Russian deputy foreign minister Sergei Ryabkov said. “The American side declares that it is interested in the elimination of [ISIS] … but some of its actions show it is doing the opposite and that some political and geopolitical goals are more important for Washington.”

This is not the first time that the two sides have traded jabs over attacks in east Syria. Earlier this month, the SDF and the Pentagon accused Russia of shelling an SDF position in Deir Ezzor’s industrial zone. Last week, Russia said that it would target SDF positions in east Syria if pro-government forces come under fire from the group.

Moscow’s warning came after Russia accused the SDF of opening fire on Syrian troops and allied forces on the eastern bank of the Euphrates twice last week. Moscow has also accused the SDF of hindering government advances in the area by opening upstream dams to prevent its allies from crossing.

In an attempt to prevent an outbreak of clashes, U.S. and Russian generals held a face-to-face meeting to discuss operations in Deir Ezzor last week.

“The discussions emphasized the need to share operational graphics and locations to ensure … prevention of accidental targeting or other possible frictions that would distract from the defeat of ISIS,” Col. Ryan Dillon said.

Monday’s attack undermines earlier talks and signals that the U.S. and Russia have yet to reach an agreement over the oil-rich zone coveted by all sides. With Monday’s attacks, it would seem that oil-rich areas east of the Euphrates will serve as a testing ground for U.S. and Russian de-confliction arrangements.

If the two sides fail to delineate areas of respective control then sporadic fighting will continue to obstruct the campaign against ISIS in the area and will leave both sides vulnerable to militant counterattacks.

Published In The Syria Deeply, 26 Sep. 2017,

Written byHashem Osseiran, Nawar Oliver

ISIS and the Strategic Vacuum- The Dilemma of Role Distribution- The Raqqa Model

Executive Summary

- The Raqqa operation closely mirrors the Mosul operation both politically and militarily. Politically, it was launched amid disagreements and a lack of clarity about which local and international forces would participate and who would govern the city post liberation. Militarily, ISIS used the same strategy it used in Mosul aiming to exhaust the attacking forces with the use of improvised explosive devices instead of direct combat. ISIS also retreated from positions near the borders of Raqqa and took more fortified positions inside neighborhoods with narrow streets in an attempt to change the battle into an urban combat nature.

- The battle uncovered critical weaknesses in the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and its ability to fight alone. The SDF required heavy cover fire from Coalition forces as well as direct involvement of American and French forces, which deployed paratroopers in the area and changed the course of the battle by taking control of the Euphrates Dam and Tabqa Military Airport.

- The tense political environment and the various interests of regional and international players will significantly impact the battle for Raqqa and future battles against ISIS in Syria.

- This paper projects four scenarios about how the Raqqa operation and future operations could play out.

- First, the United States’ continued dependence on YPG-dominated SDF forces as its sole partner, which will exacerbate tensions with Turkey.

- Second, a new agreement or arrangement between Turkey and the U.S.

- Third, a new arrangement between Russia and the U.S. in Raqqa, similar to what took place in Manbij.([1])

- Fourth, the latest Astana agreement, which could set the groundwork for the U.S. to open the way for all Astana parties to participate in the Raqqa battle.

- The most important contribution of the U.S. in Syria was undermining the “post-Aleppo status quo”([2]) established by Russia in an attempt to create an environment more consistent with an American policy that is more involved in the Middle East, especially in Syria.

Introduction

On May 18, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), of which the predominately Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG or PYD) form the main fighting force, launched an operation with a few American and French Special Forces and International Coalition air support to take Raqqa from ISIS control. According to the SDF, the battle ended on May 31, 2016, due to fierce resistance by ISIS fighters and the widespread use of mines in the rural areas surrounding Raqqa. At that time, the battle for Manbij was announced. The SDF seized control of Manbij on August 12, 2016, after which the battle for Raqqa was relaunched. In its first three phases, the battle for Raqqa achieved its desired goals: cutting off supply routes and lines of communication between ISIS’s Iraqi and Syrian branches, isolating and besieging Raqqa, and finally preparing for the offensive attack on besieged Raqqa, which is the fourth and final phase of the current operation.

The Raqqa operation closely mirrors the Mosul operation both politically and militarily. Politically, it was launched amid disagreements and a lack of clarity about which local and international forces will participate and who will govern the city post liberation. Militarily, ISIS used the same strategy it used in Mosul aiming to exhaust the attacking forces with the use of improvised explosive devices instead of direct combat. ISIS also retreated from positions near the borders of Raqqa and took more fortified positions inside neighborhoods with narrow streets in an attempt to change the battle into an urban combat nature. Furthermore, the battle uncovered critical weaknesses in the SDF’s ability to carry out the fight alone. The SDF required heavy air support from Coalition forces, as well as direct involvement of American and French forces, which deployed paratroopers in the area and changed the course of the battle by taking control of the Euphrates Dam and Tabqa Military Airport.

This paper analyzes the various political contexts surrounding the battle for Raqqa and breaks down the interests of the local and international actors involved. Furthermore, this paper projects scenarios about the governance of Raqqa post liberation, which is expected to have a significant impact on a political settlement and the future Syrian state.

Political Climate Preceding the Battle

The U.S.-led International Coalition decided to launch the battle for Raqqa depending solely on the SDF. Other groups that had previously been excluded from operations in Syria—until now—rejected the Coalition’s decision. However, similar to the way the US led international coalition initiated the operation in Mosul, their decision reflected two things: 1) the Coalition’s need to open a battle front in Syria in support of the Mosul operations, and 2) the desire for the operation to focus on fighting ISIS without allowing any participating party to exploit the battle for its own interests. Therefore, it seems that America’s choice of the YPG as the main fighting force of the SDF in Syria secured American interests, particularly by enabling Kurdish forces to participate, and created more obstacles for Turkey and Russia, whose participation in the battle remains a sore point. The battle for Raqqa is yet to begin, but the circumstances, as they are, force Turkey and Russia to align their interests more closely with America’s in the fight against ISIS if they want to participate in the fight—and in shaping the future Syrian state.

Interestingly, the dilemma of choosing partners and distributing roles is more difficult for the U.S. in the battle for Raqqa than it was in the battle for Mosul due to a number of political and military factors that make Syria different from Iraq.

A. Military Factors

The battle for Raqqa will be one of the toughest for the International Coalition because ISIS has lost significant territory in Iraq and thus will put more effort into maintaining the major cities it still controls in Syria, such as Raqqa. Furthermore, the SDF’s role in the first phases of the operation to surround Raqqa revealed that the group is not capable of carrying out the fight against ISIS in Syria on its own. This is especially concerning due to the SDF’s large numbers, with some sources estimating around 30,000 fighters. Even if we accept this inflated estimate, 30,000 fighters is significantly smaller than the force of 120,000 that is participating in the battle for Mosul, which is yet to be completed. Considering these factors, it is questionable as to how a 30,000-person force could take on ISIS in Syria.

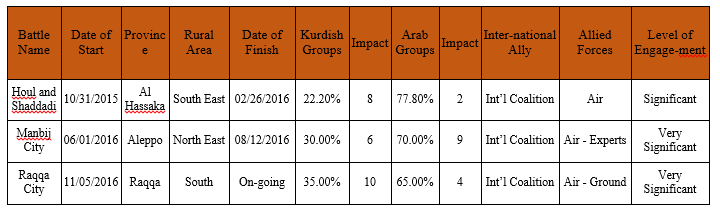

Major SDF Battles with ISIS 2016 - 2017

Measure of Level of Participation from 1 – 10

Table No. 1 Source: Monitoring Unit at Omran Center for Strategic Studies

B. Political Factors

Regional and international political interests are more aligned in Syria than they are in Iraq; however, participation of local actors is much less in Syria than in Iraq. Additionally, the government of Iraq maintains a national military, international legitimacy, and a reasonable level of national sovereignty to a much greater extent than the Assad-led government in Syria. Furthermore, the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq is a successful political project that poses little threat to other Iraqi forces. The PYD in Syria, however, is a militia that has its own political project and thus poses a threat. Furthermore, the number of international and regional actors in Iraq is far fewer than that in Syria. In Iraq, competition between international and regional actors is limited to the framework of a crisis between Turkey and Iran, and the Russian-American row is almost nonexistent; however, these complications are amplified in Syria.

The factors described above and the various interests of regional and international actors will significantly impact the battle for Raqqa and future battles against ISIS in Syria. This was clearly reflected in the reactions of various players to the announcement of the battle for Raqqa as described below.

1. Turkey - Drawing the line at National Security

For Turkey, the YPG participation in the battle for Raqqa is a red line for its national security. For this reason, Turkey’s president and other officials responded strongly to the announcement of the start of the battle, at one point threatening to close Incirlik Air Base, especially if the International Coalition were to insist that the SDF, of which the YPG makes up the bulk of the forces, leads the battle.([3]) There was also a negative atmosphere left behind due to the U.S. and the Coalition’s lack of support for Turkey’s Operation Euphrates Shield. Instead, Turkey relied on opposition forces, coordinated with Russia, and received minimal assistance from the U.S. These events revealed Turkey’s ability to launch an operation towards Raqqa with Syrian opposition forces without coordinating with the U.S. or the Coalition. Instead, Turkey could coordinate with Russia to prevent the SDF from expanding and taking over more Syrian territory. This is more likely due to statements made by Ankara that indicate its willingness to start new operations in Syria to liberate Raqqa. ([4])

Turkey also announced that it was supporting forces known as the Eastern Shield, made up of groups from eastern Syria currently operating in northern rural Aleppo.([5]) Turkey’s desire to act alone was expected after Washington ignored the Turkish proposals([6]) and after a March 7 meeting in Antalya, Turkey, about who would participate in the battle for Raqqa produced no results. So far, Washington’s position on YPG participation in the battle for Raqqa has proven to be a strong test for its relations with Ankara. Many Turkish officials have stated clearly that Washington’s insistence on the YPG’s participation in the battle will jeopardize relations between the two countries.([7])

2. Russia - Stuck in the Middle

Russia views U.S. involvement in the fight against ISIS and the increased number of American troops in Syria as a threat to its political prowess and its control of the military situation on the ground. This was especially the case during the Obama administration. In fact, launching the battle for Raqqa without coordinating with Moscow, coupled with the U.S.’s refusal to allow regime forces or Iranian-backed militias to participate, which meant Moscow would not be included either. This led Russian officials to make a number of statements demanding to participate in the operations. Moscow indicated its desire to coordinate with the SDF and the International Coalition in the fight to take Raqqa, even after the American strikes on the Sheirat Airbase and after Russia announced its cancellation of military cooperation with the U.S. in Syria. The Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov sent conciliatory messages to the Americans regarding the battle for Raqqa hoping to unite efforts between Russia and the International Coalition in fighting terrorism in Syria.([8]) The U.S. continues to reject Russian attempts to legitimize the Assad regime in the battle of Raqqa. Instead, America has conditioned any Russian role in Raqqa on reaching an understanding about a political solution in Syria that addresses Bashar al Assad’s future role in Syria. Until now, this remains a difficult task to achieve.

Russia is dealing with this American predicament surrounding the battle for Raqqa and must make a decision on who its allies will be. There are possibly two options: either give up its alliance with Iran and Assad and move closer to the U.S. or continue with its Assad/Iran alliance. If Russia chooses the second option, then it will lose any opportunity to be a partner in any internationally endorsed solution. Instead, Russia will be considered part of the problem. At the same time, Moscow is trying its best to create a third option by playing on the disagreement between Turkey and the U.S. regarding the role of the Kurdish militia in the battle for Raqqa. This Russian plan may be the one that appeals to all parties, similar to what happened in Manbij.([9]) The plan aims to encourage the U.S. to coordinate with Russia in the battle for Raqqa by allowing Assad regime forces to be included in the operations. Assad’s forces will enter into certain areas forming a buffer between the SDF and Turkish-backed forces with American and Russian oversight. This plan does not require undoing any existing agreements made after the fall of Aleppo, especially between Russia and Turkey. Turkey is not completely disturbed by the regime’s military activities in northern Syria since the placement of regime forces effectively separates the Kurdish cantons—Qamishli, Ain al Arab, Kobani (east of the Euphrates River), and Afrin (west of the river). This is exactly what Ankara wants.([10]) This would also ensure that Turkish-U.S. relations are not negatively impacted due to the less problematic Kurdish issue, if such a plan succeeds.([11])

3. Iran - Weary of All Parties

Iran rejected the new American presence in Syria. Iran also denied reports that the American incursion into Syria occurred based on an agreement between the two.([12]) Coming from Ali Larijani, chairman of the Parliament of Iran, this position reflected Iran’s fears of not only being excluded from the fight against terror but also a wholesale change in policy against the country, especially by the Trump administration. Trump considers Iran to be the main sponsor of terrorism in the region and considers its official forces and the militias it supports to be in the same camp as the terror groups in Syria. These are critical strategic challenges facing Iran that could change its future role in the region. Iran will specifically find it difficult to manage issues where its interests are in competition with the policies of the new American administration—in Iraq, where Baghdad is cozying up to Washington on the back of the Mosul operations, coupled with the increased American presence in Iraq and Syria, where America has deployed Marines in the North.([13])

Iran is also skeptical of Russia’s regional activities, such as its closer relations with Turkey. Furthermore, Iran is concerned by Turkey sending military forces into northern Syria, which weakens Iran’s ability to expand. Iran is also troubled by Russia’s willingness to sell out Iran and its militias in an American-Russian deal that would protect Russia’s interests. This is especially true after Israel stepped in to pressure both Moscow and Washington to put an end to the presence of Iranian-backed militias in Syria.

4. Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) - Avoiding the Cracks

The PYD is taking advantage of America’s predicament in choosing its best allies by presenting itself as a lesser of two evils for the U.S. The YPG is also trying to show flexibility by complying with American demands, such as including as many Arab fighters as possible in the fight for Raqqa and announcing that Raqqa will be administered by a local council comprising residents of Raqqa while still a part of the “Democratic Nation,” according to Salih Muslim, current co-chair of the PYD.([14]) For its part the YPG and its affiliated militias’ have shown success in the battle of Raqqa their ability to play politics with major regional and international actors while avoiding increased tensions between the US and Turkey, as well as Russia and the U.S. For now, the YPG separatist project depends on agreements made by major players—and what took place in Manbij is the strongest indication of what is possible.

As for its position towards Ankara, the SDF released increasingly stern statements about Turkish participation in the battle for Raqqa. It has tried to force its position on the U.S. On one occasion, Talal Sello, SDF spokesperson, claimed that he informed the U.S. that it was unacceptable for Turkey to have any role in the operation to retake Raqqa.([15]) In response, the U.S.-led International Coalition’s spokesperson John Dorrian failed to make clear whether Turkey would participate. Instead, he suggested that Turkey’s role was still being discussed on both military and diplomatic levels. He added that the Coalition was open to Turkey playing a role in the liberation of Raqqa and that talks would continue until a logical plan was reached.([16])

In response to the SDF’s statements and American ambivalence, Turkey shifted yet again from threatening rhetoric to real movements on the ground similar to what took place in Manbij. There are serious reports about a possible Turkish military operation against the Kurds in northern Syria. Reports show that Turkey has sent significant military assets to the border area. In addition, the Turkish Air Force has been striking PKK([17]) positions in Syria. Under these circumstances, American troops in northern Syria have become monitors to ensure limited military exchanges between YPG and Turkish troops in northern Syria. For this purpose, American troops were deployed to the Turkish-Syrian border to make sure the two sides do not engage. However, this does not necessitate a favorable stance from the U.S. towards the Kurds. The Trump administration is still studying alternatives to Obama’s Raqqa plan, which it believes was full of shortcomings, especially with respect to sidelining Turkey’s armed forces. What we can be sure of regarding American policy on Raqqa is that the U.S. is convinced that the Kurds must leave Raqqa as soon as they clear the city of ISIS forces. The previous U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, who indicated that the Kurds knew that they would have to hand the city over to Arab forces as soon as they took over, confirmed this.

Even Samantha Power, former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, insisted that starting any operation in Raqqa without Turkey would hurt the relationship between the two countries and would put Washington in an embarrassing situation for supporting a group that has conducted terror attacks against a NATO ally.([18])

The Start of the Battle and the Military Situation

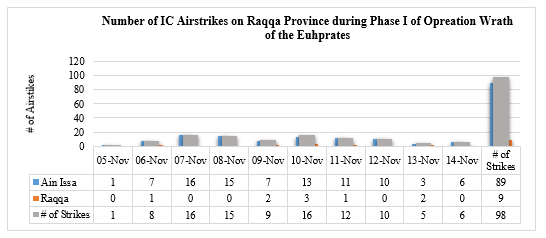

Amid this politically charged environment, the SDF announced the start of its operation to take Raqqa under the name “Wrath of the Euphrates.” Its plan was to isolate the city starting from the southern rural areas of Ain Issa with heavy air support from the U.S.-led international coalition. On November 14, 2016, the SDF announced the end of phase 1 of their operation after taking 500 square kilometers of territory from ISIS.

From its start, the operation focused on the rural areas south of Ain Issa, which are easy to take unlike residential areas. However, the situation was not so simple since ISIS depended on improvised explosive devices (IEDs), which were planted randomly around Ain Issa causing serious damage to the SDF. The presence of IEDs was the main reason for the heavy Coalition strike on areas where there were no ISIS forces present.

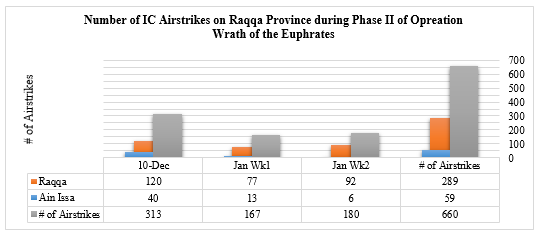

The second phase of Operation Wrath of the Euphrates started on December 10, 2016, aiming to take control of Raqqa’s western rural areas along the banks of the Euphrates River. The most significant development in this phase of the battle was the SDF’s announcement of new parties joining the operation:

- The Elite Forces of the Syrian Future Movement led by Ahmad Al Jarba after his deal with Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM).

- The Military Council of Deir Ezzor.

- Some Arab tribes from the area.

In the announcement came a confirmation by Jihan Sheikh Ahmed, a spokesperson for the Wrath of the Euphrates Operation, of successful coordination with the Coalition in the previous phase and the expectation of continued coordination.

The second phase of the operation lasted until January 16, 2017, during which 2,480 square kilometers were taken over from ISIS, as well as important places such as the historic Qalet Jaber.

On February 4, 2017, the SDF announced the start of the third phase of Operation Euphrates Shield. This phase of the operation aimed to cut off lines of communication between Raqqa and Deir Ezzor and to make significant advances from the North and the West on ISIS’s self-declared capital.

In mid-March 2017, Coalition airstrikes intensified on Tabqa and the surrounding areas, reaching 125 strikes between March 17 and 26. On March 25, an offensive was launched to seize control of the 4 km-long Euphrates Dam in Tabqa. On March 26, the dam was struck by Coalition airstrikes making it non-operational.

Despite the heavy Coalition airstrikes, the YPG and its allies were unable to take the dam due to the large number of IEDs planted by ISIS. According to field interviews conducted by Omran Center, American troops landed in western rural Tabqa as YPG-led forces crossed the Euphrates River. An attack ensued on the Tabqa Military Airport from the South without striking the city itself.

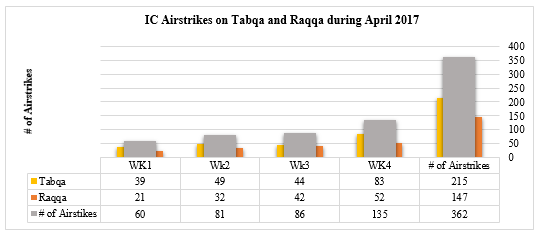

On the evening of March 26, the YPG announced control over the military airport and immediately after—with oversight by American and French troops—the YPG started operations to take control of the rural parts of the city. By mid-April, the city was besieged and operations began to take the city with a significant uptick in Coalition airstrikes. Airstrikes on Tabqa city during the month of April 2017 reached 215 strikes, making Tabqa the most targeted city by the Coalition during that month, as shown below.

Forces involved in the Tabqa offensive: The Americans headed up the landing south of the Euphrates. French troops were present at Jabar on the other side of the river and were able to secure boat crossings for the YPG to the other side. Coalition forces wanted to take Tabqa Military Airport to make it a base for future operations and eventually for the complete siege of Tabqa. As for the YPG, its role was limited to protecting the backs of the Coalition forces and then moving in when the Coalition leaves.

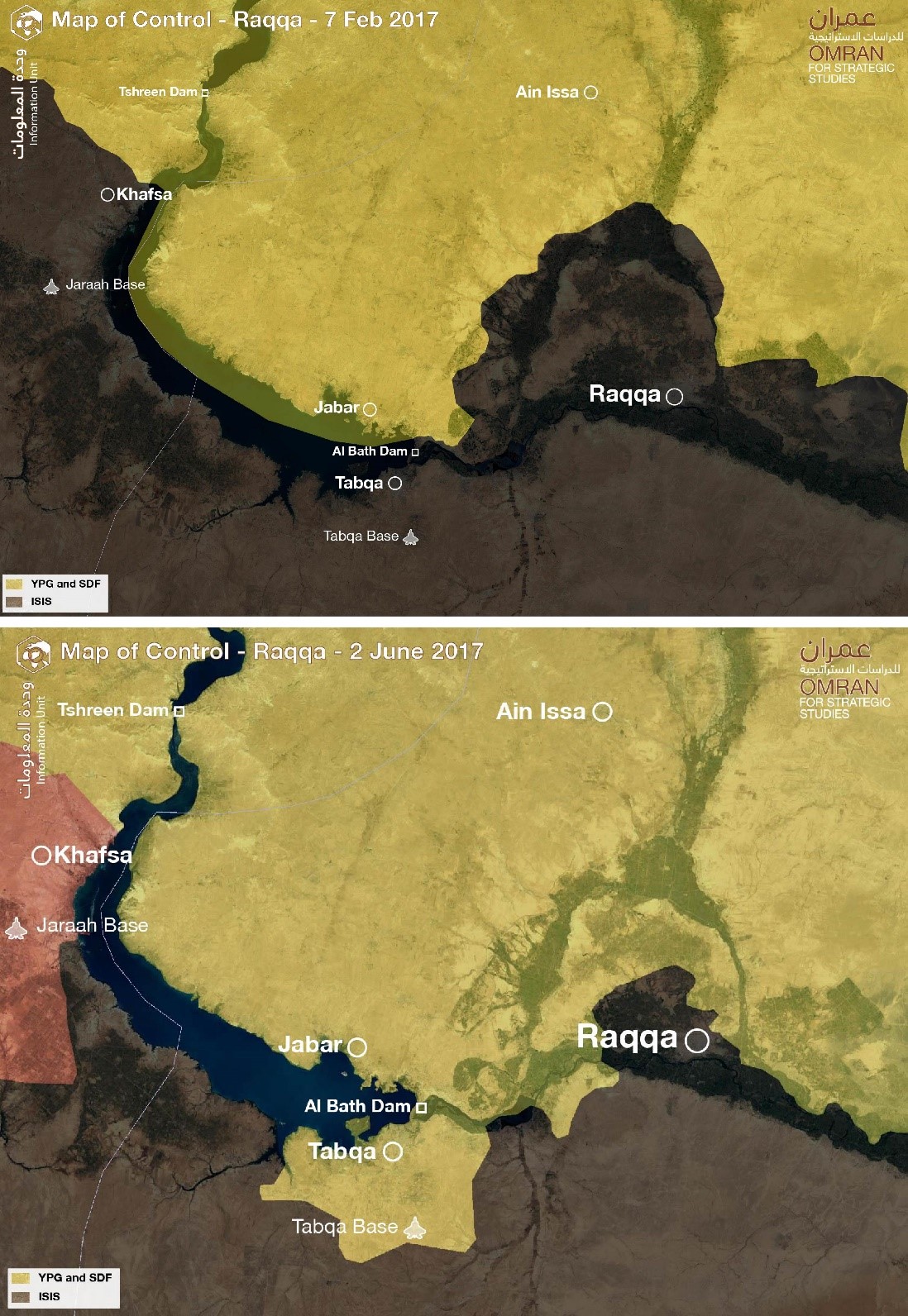

Map No. (1) Control and Influence of Raqqa and Tabqa, between 7 February 2017 and 2 June 2017

On April 13, the SDF announced the fourth phase of Operation Wrath of the Euphrates that aimed to take what remained of northern rural Raqqa and Jallab Valley, according to a statement released by the Wrath of the Euphrates operations room.([19])

Even though the SDF announced the fourth phase of Operation Wrath of the Euphrates, and previous phases achieved their stated goals, it was not able to take full control of Tabqa city until May 4, 2017. Furthermore, that only happened after making a deal with ISIS to let its fighters and their family members leave towards Deir Ezzor.([20])

Costs of the Battle (Infrastructure and Civilians):

Coalition strikes in September 2016 destroyed the remaining bridges that crossed the Euphrates River between the Iraqi border and eastern Raqqa. Additional raids destroyed the city's bridges on February 3, 2017. The Euphrates Dam was also damaged because of the clashes and now, with a damaged control room and the introduction of melting snow, the dam's status is questionable, with the water level increasing 10 meters since the beginning of the year.

The dam is now non-operational due to clashes between Kurdish fighters and ISIS, coupled with Coalition strikes. This has caused major concerns because if the dam breaks, the water could submerge more than one third of Syria and large parts of Iraq, reaching Ramadi.

Almost all of the hospitals in rural Raqqa are out of service. The only hospital remaining is operating at one fourth of its capacity even though there are approximately 200,000 civilians living there.([21])

On March 21, 2017, more than 200 civilians were killed and wounded in a Coalition strike on a school inhabited by displaced persons in the town of Mansoura in rural Raqqa.([22])

Again, on March 22, 2017, Coalition strikes committed another attack in Tabqa, west of Raqqa, targeting a bakery in a busy market killing at least 25 civilians and injuring more than 40 others.([23]) On April 22, 2017, another five civilians were killed and tens were injured in a Coalition airstrike on Tabqa.

In a mistaken strike by Coalition forces, 18 SDF fighters were killed south of Tabqa. The coalition released a statement explaining that the strike was conducted based on a request from one of its partners and the target was identified as an ISIS fighting position. The statement explained that the target was actually a front position of the SDF.([24])

Battle Scenarios

Even though the SDF is dominating the headlines and appears as the ideal force to liberate Raqqa, a number of factors indicate that there is more than one plausible scenario for the liberation of Raqqa. The issue is not determined solely by the force that will do the bulk of the fighting but also, who will administer the city after it is retaken, who will go after ISIS forces fleeing the city, and who will attack the last ISIS stronghold in Deir Ezzor, Syria.

The factors influencing the drawing up of possible battle scenarios are as follows:

- The SDF is unable to carry out the fight alone, evidenced by the need for direct participation from Coalition ground forces in critical positions and the increased number of American troops in Syria. Furthermore, the SDF has been ineffective in identifying enemy positions resulting in a large number of civilian deaths and even the deaths of 18 of its own fighters.

- Raqqa’s geographical positioning is quite difficult to deal with. It is open to Hassaka to the northeast and Deir Ezzor to the south, which is open to Iraq’s southeast. To the west, Raqqa is open to Hama and Homs, and to the north, Raqqa is open to Turkey. This requires a complicated coordination effort between local and international forces that must participate to make any final offensive effective.

- There is an ongoing struggle over ISIS’ legacy and the areas that it will leave behind that cover a significant geographic area. This issue is directly linked to the shaping of a political solution in Syria, which has put the battle of Raqqa under the pressures of conflicting interests of local, regional, and international actors involved in Syria.

- The Trump administration found itself in a predicament when it realized that the Obama administration’s Raqqa plan depended too heavily on arming and supporting Kurdish forces. On the contrary, the Trump administration adopted a policy of improving ties with Turkey and working closely with Russia to reach a political settlement to the Syrian crisis.

Given these factors, it is possible to project the following four scenarios for the battle of Raqqa:

First Scenario

The U.S. would continue to exclusively depend on the YPG and make serious attempts to take advantage of the Arab forces that are currently an inactive part of the SDF. This would balance out the influence of the PYD in the SDF. After Raqqa is liberated, it would be handed to a local council that represents the local population, as is being planned for now. This scenario seems more likely if we look at the increasing number of American troops in Syria. There are also 1,000 American Special Forces deployed in Kuwait on standby ready to be called in to support operations in Syria or Iraq. President Trump has also given the army the authority to determine appropriate troop levels in both Iraq and Syria.([25]) In this scenario, the U.S. would be able to conduct a successful operation to take Raqqa but with a significant footprint, including direct combat and an extended period. Moreover, the political issues would remain unresolved, especially with respect to Turkey. These unresolved political issues could heighten tensions between Turkey and the U.S. after the battle for Raqqa, especially since Turkey insists that the SDF refrain from taking control of any other territory and that current SDF-controlled territory be disconnected. Increased tensions with the U.S. may lead to a solution in this scenario that is something similar to what happened in Manbij.([26]) Moscow is hoping that it can take advantage of Turkish-American tensions in order to push the participation of regime forces as a legitimate option.

Second Scenario

The U.S. and Turkey would increase their coordination in Syria while pushing the PYD forces farther away. This would happen according to one of two Turkish plans. The first is that Turkish forces enter Syria towards Raqqa from Tal Abyad and the SDF opens a 25-km corridor for them. This would mean the PYD loses control of Tal Abyad and cuts off unobstructed access between Qamishli and Ain Arab (Kobani), which is unlikely. The other option is for Turkish forces to enter from Al Bab, which would mean either attacking regime forces or coordinating with them to secure a corridor access to Raqqa. It is unclear until now if the Trump administration is willing to completely give up its coordination with the SDF. In addition, the option of having Turkish-backed Arab forces fighting alongside the SDF is unlikely since both Turkey and the SDF reject such a proposal. Turkey will not participate in the battle if the other party includes PYD forces.

Third Scenario