Ayman al-Dassouky: talking about the lucrative trade business across front lines between Syrian opposition held and regime territory

In an interview with AFP, Ayman al-Dassouky gives his analysis about the lucrative trade business across front lines between Syrian opposition held and regime territory

The crossings generated millions for the forces which contr it by businessmen who trade across them," and It brings mutual benefit to the warring sides who have allied themselves to boost trade..

Source: https://yhoo.it/2M6g54f

Dr. Ammar Kahf, Commented on latest developments in southern Syria

On the 25th of July, Dr. Ammar Kahf, the executive director of the Omran, commented on latest developments in southern Syria to USA Today, by stating that the regime’s territorial gains in Daraa has put Iran and Hezbollah closer to being a threat to Israel and regional powers.

This development will increase the likelihood of greater conflict in the Middle East. Developments in Daraa are also signs of a new era in the Syrian conflict, where domestic actors have largely disappeared and given way to international and non-state actors using Syria for their own agenda.

Dr. Kahf has stated that “The story of the armed Syrian opposition is over, Iran and Hezbollah are much stronger today than a month ago and closer to the southern front. I think this (Syrian conflict) will continue to escalate.”

Special thanks to the co-writers of the Article, Jacob Wirtschafter and Gilgamesh Nabeel.

Source: https://usat.ly/2NPpBc6

ISIS and the Strategic Vacuum- The Dilemma of Role Distribution- The Raqqa Model

Executive Summary

- The Raqqa operation closely mirrors the Mosul operation both politically and militarily. Politically, it was launched amid disagreements and a lack of clarity about which local and international forces would participate and who would govern the city post liberation. Militarily, ISIS used the same strategy it used in Mosul aiming to exhaust the attacking forces with the use of improvised explosive devices instead of direct combat. ISIS also retreated from positions near the borders of Raqqa and took more fortified positions inside neighborhoods with narrow streets in an attempt to change the battle into an urban combat nature.

- The battle uncovered critical weaknesses in the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and its ability to fight alone. The SDF required heavy cover fire from Coalition forces as well as direct involvement of American and French forces, which deployed paratroopers in the area and changed the course of the battle by taking control of the Euphrates Dam and Tabqa Military Airport.

- The tense political environment and the various interests of regional and international players will significantly impact the battle for Raqqa and future battles against ISIS in Syria.

- This paper projects four scenarios about how the Raqqa operation and future operations could play out.

- First, the United States’ continued dependence on YPG-dominated SDF forces as its sole partner, which will exacerbate tensions with Turkey.

- Second, a new agreement or arrangement between Turkey and the U.S.

- Third, a new arrangement between Russia and the U.S. in Raqqa, similar to what took place in Manbij.([1])

- Fourth, the latest Astana agreement, which could set the groundwork for the U.S. to open the way for all Astana parties to participate in the Raqqa battle.

- The most important contribution of the U.S. in Syria was undermining the “post-Aleppo status quo”([2]) established by Russia in an attempt to create an environment more consistent with an American policy that is more involved in the Middle East, especially in Syria.

Introduction

On May 18, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), of which the predominately Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG or PYD) form the main fighting force, launched an operation with a few American and French Special Forces and International Coalition air support to take Raqqa from ISIS control. According to the SDF, the battle ended on May 31, 2016, due to fierce resistance by ISIS fighters and the widespread use of mines in the rural areas surrounding Raqqa. At that time, the battle for Manbij was announced. The SDF seized control of Manbij on August 12, 2016, after which the battle for Raqqa was relaunched. In its first three phases, the battle for Raqqa achieved its desired goals: cutting off supply routes and lines of communication between ISIS’s Iraqi and Syrian branches, isolating and besieging Raqqa, and finally preparing for the offensive attack on besieged Raqqa, which is the fourth and final phase of the current operation.

The Raqqa operation closely mirrors the Mosul operation both politically and militarily. Politically, it was launched amid disagreements and a lack of clarity about which local and international forces will participate and who will govern the city post liberation. Militarily, ISIS used the same strategy it used in Mosul aiming to exhaust the attacking forces with the use of improvised explosive devices instead of direct combat. ISIS also retreated from positions near the borders of Raqqa and took more fortified positions inside neighborhoods with narrow streets in an attempt to change the battle into an urban combat nature. Furthermore, the battle uncovered critical weaknesses in the SDF’s ability to carry out the fight alone. The SDF required heavy air support from Coalition forces, as well as direct involvement of American and French forces, which deployed paratroopers in the area and changed the course of the battle by taking control of the Euphrates Dam and Tabqa Military Airport.

This paper analyzes the various political contexts surrounding the battle for Raqqa and breaks down the interests of the local and international actors involved. Furthermore, this paper projects scenarios about the governance of Raqqa post liberation, which is expected to have a significant impact on a political settlement and the future Syrian state.

Political Climate Preceding the Battle

The U.S.-led International Coalition decided to launch the battle for Raqqa depending solely on the SDF. Other groups that had previously been excluded from operations in Syria—until now—rejected the Coalition’s decision. However, similar to the way the US led international coalition initiated the operation in Mosul, their decision reflected two things: 1) the Coalition’s need to open a battle front in Syria in support of the Mosul operations, and 2) the desire for the operation to focus on fighting ISIS without allowing any participating party to exploit the battle for its own interests. Therefore, it seems that America’s choice of the YPG as the main fighting force of the SDF in Syria secured American interests, particularly by enabling Kurdish forces to participate, and created more obstacles for Turkey and Russia, whose participation in the battle remains a sore point. The battle for Raqqa is yet to begin, but the circumstances, as they are, force Turkey and Russia to align their interests more closely with America’s in the fight against ISIS if they want to participate in the fight—and in shaping the future Syrian state.

Interestingly, the dilemma of choosing partners and distributing roles is more difficult for the U.S. in the battle for Raqqa than it was in the battle for Mosul due to a number of political and military factors that make Syria different from Iraq.

A. Military Factors

The battle for Raqqa will be one of the toughest for the International Coalition because ISIS has lost significant territory in Iraq and thus will put more effort into maintaining the major cities it still controls in Syria, such as Raqqa. Furthermore, the SDF’s role in the first phases of the operation to surround Raqqa revealed that the group is not capable of carrying out the fight against ISIS in Syria on its own. This is especially concerning due to the SDF’s large numbers, with some sources estimating around 30,000 fighters. Even if we accept this inflated estimate, 30,000 fighters is significantly smaller than the force of 120,000 that is participating in the battle for Mosul, which is yet to be completed. Considering these factors, it is questionable as to how a 30,000-person force could take on ISIS in Syria.

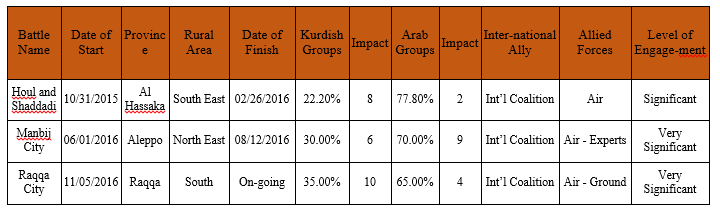

Major SDF Battles with ISIS 2016 - 2017

Measure of Level of Participation from 1 – 10

Table No. 1 Source: Monitoring Unit at Omran Center for Strategic Studies

B. Political Factors

Regional and international political interests are more aligned in Syria than they are in Iraq; however, participation of local actors is much less in Syria than in Iraq. Additionally, the government of Iraq maintains a national military, international legitimacy, and a reasonable level of national sovereignty to a much greater extent than the Assad-led government in Syria. Furthermore, the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq is a successful political project that poses little threat to other Iraqi forces. The PYD in Syria, however, is a militia that has its own political project and thus poses a threat. Furthermore, the number of international and regional actors in Iraq is far fewer than that in Syria. In Iraq, competition between international and regional actors is limited to the framework of a crisis between Turkey and Iran, and the Russian-American row is almost nonexistent; however, these complications are amplified in Syria.

The factors described above and the various interests of regional and international actors will significantly impact the battle for Raqqa and future battles against ISIS in Syria. This was clearly reflected in the reactions of various players to the announcement of the battle for Raqqa as described below.

1. Turkey - Drawing the line at National Security

For Turkey, the YPG participation in the battle for Raqqa is a red line for its national security. For this reason, Turkey’s president and other officials responded strongly to the announcement of the start of the battle, at one point threatening to close Incirlik Air Base, especially if the International Coalition were to insist that the SDF, of which the YPG makes up the bulk of the forces, leads the battle.([3]) There was also a negative atmosphere left behind due to the U.S. and the Coalition’s lack of support for Turkey’s Operation Euphrates Shield. Instead, Turkey relied on opposition forces, coordinated with Russia, and received minimal assistance from the U.S. These events revealed Turkey’s ability to launch an operation towards Raqqa with Syrian opposition forces without coordinating with the U.S. or the Coalition. Instead, Turkey could coordinate with Russia to prevent the SDF from expanding and taking over more Syrian territory. This is more likely due to statements made by Ankara that indicate its willingness to start new operations in Syria to liberate Raqqa. ([4])

Turkey also announced that it was supporting forces known as the Eastern Shield, made up of groups from eastern Syria currently operating in northern rural Aleppo.([5]) Turkey’s desire to act alone was expected after Washington ignored the Turkish proposals([6]) and after a March 7 meeting in Antalya, Turkey, about who would participate in the battle for Raqqa produced no results. So far, Washington’s position on YPG participation in the battle for Raqqa has proven to be a strong test for its relations with Ankara. Many Turkish officials have stated clearly that Washington’s insistence on the YPG’s participation in the battle will jeopardize relations between the two countries.([7])

2. Russia - Stuck in the Middle

Russia views U.S. involvement in the fight against ISIS and the increased number of American troops in Syria as a threat to its political prowess and its control of the military situation on the ground. This was especially the case during the Obama administration. In fact, launching the battle for Raqqa without coordinating with Moscow, coupled with the U.S.’s refusal to allow regime forces or Iranian-backed militias to participate, which meant Moscow would not be included either. This led Russian officials to make a number of statements demanding to participate in the operations. Moscow indicated its desire to coordinate with the SDF and the International Coalition in the fight to take Raqqa, even after the American strikes on the Sheirat Airbase and after Russia announced its cancellation of military cooperation with the U.S. in Syria. The Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov sent conciliatory messages to the Americans regarding the battle for Raqqa hoping to unite efforts between Russia and the International Coalition in fighting terrorism in Syria.([8]) The U.S. continues to reject Russian attempts to legitimize the Assad regime in the battle of Raqqa. Instead, America has conditioned any Russian role in Raqqa on reaching an understanding about a political solution in Syria that addresses Bashar al Assad’s future role in Syria. Until now, this remains a difficult task to achieve.

Russia is dealing with this American predicament surrounding the battle for Raqqa and must make a decision on who its allies will be. There are possibly two options: either give up its alliance with Iran and Assad and move closer to the U.S. or continue with its Assad/Iran alliance. If Russia chooses the second option, then it will lose any opportunity to be a partner in any internationally endorsed solution. Instead, Russia will be considered part of the problem. At the same time, Moscow is trying its best to create a third option by playing on the disagreement between Turkey and the U.S. regarding the role of the Kurdish militia in the battle for Raqqa. This Russian plan may be the one that appeals to all parties, similar to what happened in Manbij.([9]) The plan aims to encourage the U.S. to coordinate with Russia in the battle for Raqqa by allowing Assad regime forces to be included in the operations. Assad’s forces will enter into certain areas forming a buffer between the SDF and Turkish-backed forces with American and Russian oversight. This plan does not require undoing any existing agreements made after the fall of Aleppo, especially between Russia and Turkey. Turkey is not completely disturbed by the regime’s military activities in northern Syria since the placement of regime forces effectively separates the Kurdish cantons—Qamishli, Ain al Arab, Kobani (east of the Euphrates River), and Afrin (west of the river). This is exactly what Ankara wants.([10]) This would also ensure that Turkish-U.S. relations are not negatively impacted due to the less problematic Kurdish issue, if such a plan succeeds.([11])

3. Iran - Weary of All Parties

Iran rejected the new American presence in Syria. Iran also denied reports that the American incursion into Syria occurred based on an agreement between the two.([12]) Coming from Ali Larijani, chairman of the Parliament of Iran, this position reflected Iran’s fears of not only being excluded from the fight against terror but also a wholesale change in policy against the country, especially by the Trump administration. Trump considers Iran to be the main sponsor of terrorism in the region and considers its official forces and the militias it supports to be in the same camp as the terror groups in Syria. These are critical strategic challenges facing Iran that could change its future role in the region. Iran will specifically find it difficult to manage issues where its interests are in competition with the policies of the new American administration—in Iraq, where Baghdad is cozying up to Washington on the back of the Mosul operations, coupled with the increased American presence in Iraq and Syria, where America has deployed Marines in the North.([13])

Iran is also skeptical of Russia’s regional activities, such as its closer relations with Turkey. Furthermore, Iran is concerned by Turkey sending military forces into northern Syria, which weakens Iran’s ability to expand. Iran is also troubled by Russia’s willingness to sell out Iran and its militias in an American-Russian deal that would protect Russia’s interests. This is especially true after Israel stepped in to pressure both Moscow and Washington to put an end to the presence of Iranian-backed militias in Syria.

4. Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) - Avoiding the Cracks

The PYD is taking advantage of America’s predicament in choosing its best allies by presenting itself as a lesser of two evils for the U.S. The YPG is also trying to show flexibility by complying with American demands, such as including as many Arab fighters as possible in the fight for Raqqa and announcing that Raqqa will be administered by a local council comprising residents of Raqqa while still a part of the “Democratic Nation,” according to Salih Muslim, current co-chair of the PYD.([14]) For its part the YPG and its affiliated militias’ have shown success in the battle of Raqqa their ability to play politics with major regional and international actors while avoiding increased tensions between the US and Turkey, as well as Russia and the U.S. For now, the YPG separatist project depends on agreements made by major players—and what took place in Manbij is the strongest indication of what is possible.

As for its position towards Ankara, the SDF released increasingly stern statements about Turkish participation in the battle for Raqqa. It has tried to force its position on the U.S. On one occasion, Talal Sello, SDF spokesperson, claimed that he informed the U.S. that it was unacceptable for Turkey to have any role in the operation to retake Raqqa.([15]) In response, the U.S.-led International Coalition’s spokesperson John Dorrian failed to make clear whether Turkey would participate. Instead, he suggested that Turkey’s role was still being discussed on both military and diplomatic levels. He added that the Coalition was open to Turkey playing a role in the liberation of Raqqa and that talks would continue until a logical plan was reached.([16])

In response to the SDF’s statements and American ambivalence, Turkey shifted yet again from threatening rhetoric to real movements on the ground similar to what took place in Manbij. There are serious reports about a possible Turkish military operation against the Kurds in northern Syria. Reports show that Turkey has sent significant military assets to the border area. In addition, the Turkish Air Force has been striking PKK([17]) positions in Syria. Under these circumstances, American troops in northern Syria have become monitors to ensure limited military exchanges between YPG and Turkish troops in northern Syria. For this purpose, American troops were deployed to the Turkish-Syrian border to make sure the two sides do not engage. However, this does not necessitate a favorable stance from the U.S. towards the Kurds. The Trump administration is still studying alternatives to Obama’s Raqqa plan, which it believes was full of shortcomings, especially with respect to sidelining Turkey’s armed forces. What we can be sure of regarding American policy on Raqqa is that the U.S. is convinced that the Kurds must leave Raqqa as soon as they clear the city of ISIS forces. The previous U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, who indicated that the Kurds knew that they would have to hand the city over to Arab forces as soon as they took over, confirmed this.

Even Samantha Power, former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, insisted that starting any operation in Raqqa without Turkey would hurt the relationship between the two countries and would put Washington in an embarrassing situation for supporting a group that has conducted terror attacks against a NATO ally.([18])

The Start of the Battle and the Military Situation

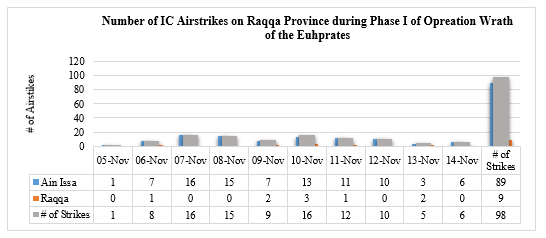

Amid this politically charged environment, the SDF announced the start of its operation to take Raqqa under the name “Wrath of the Euphrates.” Its plan was to isolate the city starting from the southern rural areas of Ain Issa with heavy air support from the U.S.-led international coalition. On November 14, 2016, the SDF announced the end of phase 1 of their operation after taking 500 square kilometers of territory from ISIS.

From its start, the operation focused on the rural areas south of Ain Issa, which are easy to take unlike residential areas. However, the situation was not so simple since ISIS depended on improvised explosive devices (IEDs), which were planted randomly around Ain Issa causing serious damage to the SDF. The presence of IEDs was the main reason for the heavy Coalition strike on areas where there were no ISIS forces present.

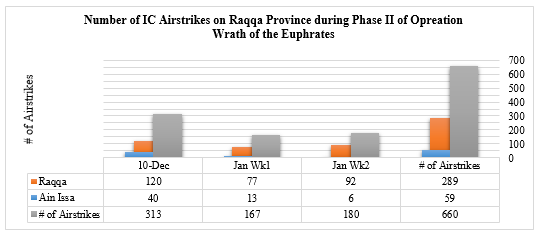

The second phase of Operation Wrath of the Euphrates started on December 10, 2016, aiming to take control of Raqqa’s western rural areas along the banks of the Euphrates River. The most significant development in this phase of the battle was the SDF’s announcement of new parties joining the operation:

- The Elite Forces of the Syrian Future Movement led by Ahmad Al Jarba after his deal with Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM).

- The Military Council of Deir Ezzor.

- Some Arab tribes from the area.

In the announcement came a confirmation by Jihan Sheikh Ahmed, a spokesperson for the Wrath of the Euphrates Operation, of successful coordination with the Coalition in the previous phase and the expectation of continued coordination.

The second phase of the operation lasted until January 16, 2017, during which 2,480 square kilometers were taken over from ISIS, as well as important places such as the historic Qalet Jaber.

On February 4, 2017, the SDF announced the start of the third phase of Operation Euphrates Shield. This phase of the operation aimed to cut off lines of communication between Raqqa and Deir Ezzor and to make significant advances from the North and the West on ISIS’s self-declared capital.

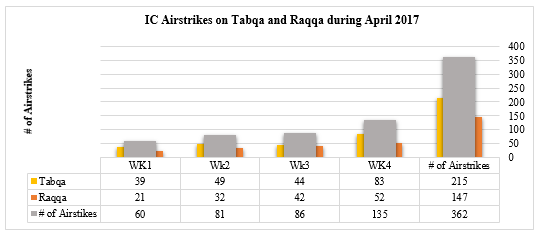

In mid-March 2017, Coalition airstrikes intensified on Tabqa and the surrounding areas, reaching 125 strikes between March 17 and 26. On March 25, an offensive was launched to seize control of the 4 km-long Euphrates Dam in Tabqa. On March 26, the dam was struck by Coalition airstrikes making it non-operational.

Despite the heavy Coalition airstrikes, the YPG and its allies were unable to take the dam due to the large number of IEDs planted by ISIS. According to field interviews conducted by Omran Center, American troops landed in western rural Tabqa as YPG-led forces crossed the Euphrates River. An attack ensued on the Tabqa Military Airport from the South without striking the city itself.

On the evening of March 26, the YPG announced control over the military airport and immediately after—with oversight by American and French troops—the YPG started operations to take control of the rural parts of the city. By mid-April, the city was besieged and operations began to take the city with a significant uptick in Coalition airstrikes. Airstrikes on Tabqa city during the month of April 2017 reached 215 strikes, making Tabqa the most targeted city by the Coalition during that month, as shown below.

Forces involved in the Tabqa offensive: The Americans headed up the landing south of the Euphrates. French troops were present at Jabar on the other side of the river and were able to secure boat crossings for the YPG to the other side. Coalition forces wanted to take Tabqa Military Airport to make it a base for future operations and eventually for the complete siege of Tabqa. As for the YPG, its role was limited to protecting the backs of the Coalition forces and then moving in when the Coalition leaves.

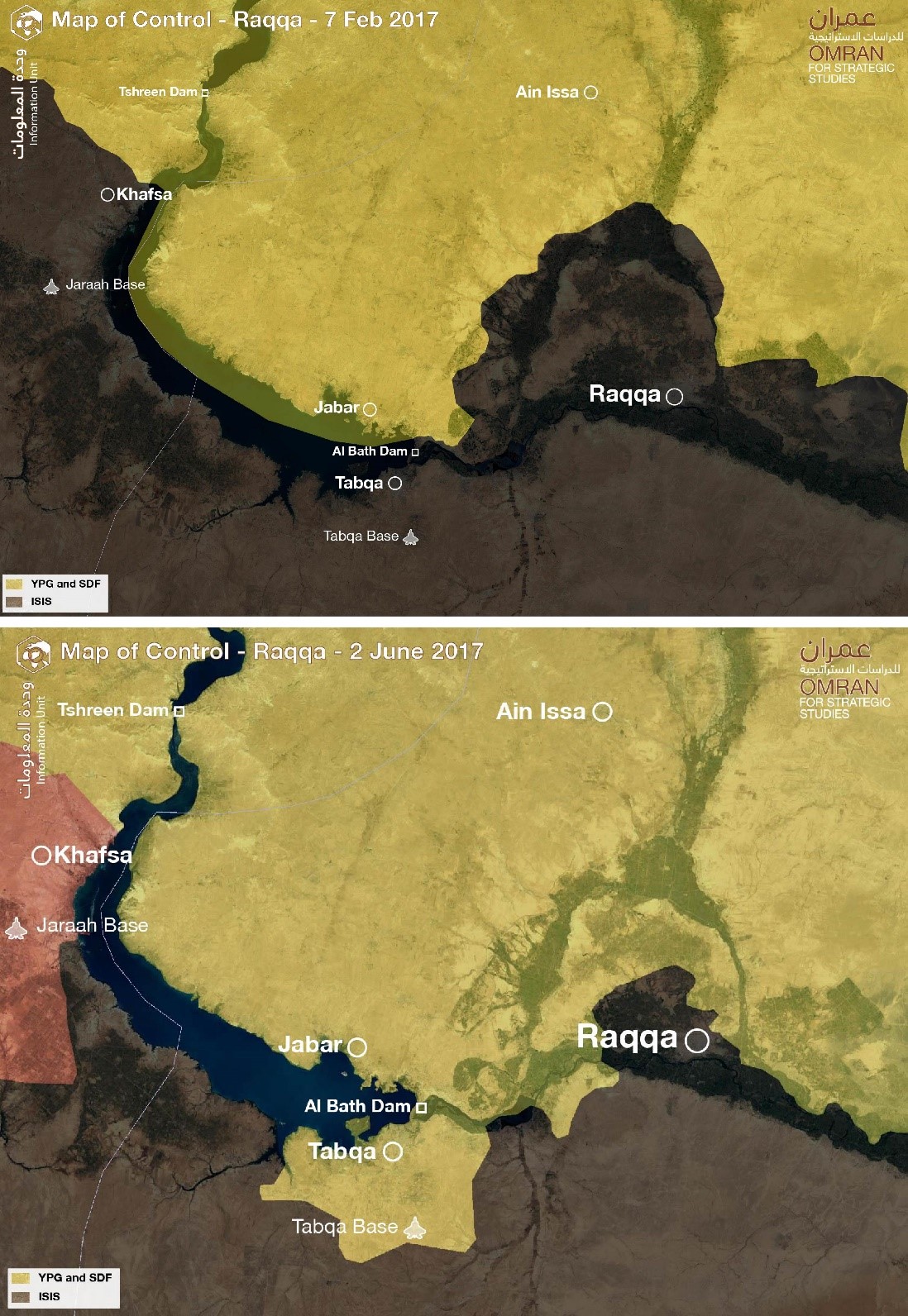

Map No. (1) Control and Influence of Raqqa and Tabqa, between 7 February 2017 and 2 June 2017

On April 13, the SDF announced the fourth phase of Operation Wrath of the Euphrates that aimed to take what remained of northern rural Raqqa and Jallab Valley, according to a statement released by the Wrath of the Euphrates operations room.([19])

Even though the SDF announced the fourth phase of Operation Wrath of the Euphrates, and previous phases achieved their stated goals, it was not able to take full control of Tabqa city until May 4, 2017. Furthermore, that only happened after making a deal with ISIS to let its fighters and their family members leave towards Deir Ezzor.([20])

Costs of the Battle (Infrastructure and Civilians):

Coalition strikes in September 2016 destroyed the remaining bridges that crossed the Euphrates River between the Iraqi border and eastern Raqqa. Additional raids destroyed the city's bridges on February 3, 2017. The Euphrates Dam was also damaged because of the clashes and now, with a damaged control room and the introduction of melting snow, the dam's status is questionable, with the water level increasing 10 meters since the beginning of the year.

The dam is now non-operational due to clashes between Kurdish fighters and ISIS, coupled with Coalition strikes. This has caused major concerns because if the dam breaks, the water could submerge more than one third of Syria and large parts of Iraq, reaching Ramadi.

Almost all of the hospitals in rural Raqqa are out of service. The only hospital remaining is operating at one fourth of its capacity even though there are approximately 200,000 civilians living there.([21])

On March 21, 2017, more than 200 civilians were killed and wounded in a Coalition strike on a school inhabited by displaced persons in the town of Mansoura in rural Raqqa.([22])

Again, on March 22, 2017, Coalition strikes committed another attack in Tabqa, west of Raqqa, targeting a bakery in a busy market killing at least 25 civilians and injuring more than 40 others.([23]) On April 22, 2017, another five civilians were killed and tens were injured in a Coalition airstrike on Tabqa.

In a mistaken strike by Coalition forces, 18 SDF fighters were killed south of Tabqa. The coalition released a statement explaining that the strike was conducted based on a request from one of its partners and the target was identified as an ISIS fighting position. The statement explained that the target was actually a front position of the SDF.([24])

Battle Scenarios

Even though the SDF is dominating the headlines and appears as the ideal force to liberate Raqqa, a number of factors indicate that there is more than one plausible scenario for the liberation of Raqqa. The issue is not determined solely by the force that will do the bulk of the fighting but also, who will administer the city after it is retaken, who will go after ISIS forces fleeing the city, and who will attack the last ISIS stronghold in Deir Ezzor, Syria.

The factors influencing the drawing up of possible battle scenarios are as follows:

- The SDF is unable to carry out the fight alone, evidenced by the need for direct participation from Coalition ground forces in critical positions and the increased number of American troops in Syria. Furthermore, the SDF has been ineffective in identifying enemy positions resulting in a large number of civilian deaths and even the deaths of 18 of its own fighters.

- Raqqa’s geographical positioning is quite difficult to deal with. It is open to Hassaka to the northeast and Deir Ezzor to the south, which is open to Iraq’s southeast. To the west, Raqqa is open to Hama and Homs, and to the north, Raqqa is open to Turkey. This requires a complicated coordination effort between local and international forces that must participate to make any final offensive effective.

- There is an ongoing struggle over ISIS’ legacy and the areas that it will leave behind that cover a significant geographic area. This issue is directly linked to the shaping of a political solution in Syria, which has put the battle of Raqqa under the pressures of conflicting interests of local, regional, and international actors involved in Syria.

- The Trump administration found itself in a predicament when it realized that the Obama administration’s Raqqa plan depended too heavily on arming and supporting Kurdish forces. On the contrary, the Trump administration adopted a policy of improving ties with Turkey and working closely with Russia to reach a political settlement to the Syrian crisis.

Given these factors, it is possible to project the following four scenarios for the battle of Raqqa:

First Scenario

The U.S. would continue to exclusively depend on the YPG and make serious attempts to take advantage of the Arab forces that are currently an inactive part of the SDF. This would balance out the influence of the PYD in the SDF. After Raqqa is liberated, it would be handed to a local council that represents the local population, as is being planned for now. This scenario seems more likely if we look at the increasing number of American troops in Syria. There are also 1,000 American Special Forces deployed in Kuwait on standby ready to be called in to support operations in Syria or Iraq. President Trump has also given the army the authority to determine appropriate troop levels in both Iraq and Syria.([25]) In this scenario, the U.S. would be able to conduct a successful operation to take Raqqa but with a significant footprint, including direct combat and an extended period. Moreover, the political issues would remain unresolved, especially with respect to Turkey. These unresolved political issues could heighten tensions between Turkey and the U.S. after the battle for Raqqa, especially since Turkey insists that the SDF refrain from taking control of any other territory and that current SDF-controlled territory be disconnected. Increased tensions with the U.S. may lead to a solution in this scenario that is something similar to what happened in Manbij.([26]) Moscow is hoping that it can take advantage of Turkish-American tensions in order to push the participation of regime forces as a legitimate option.

Second Scenario

The U.S. and Turkey would increase their coordination in Syria while pushing the PYD forces farther away. This would happen according to one of two Turkish plans. The first is that Turkish forces enter Syria towards Raqqa from Tal Abyad and the SDF opens a 25-km corridor for them. This would mean the PYD loses control of Tal Abyad and cuts off unobstructed access between Qamishli and Ain Arab (Kobani), which is unlikely. The other option is for Turkish forces to enter from Al Bab, which would mean either attacking regime forces or coordinating with them to secure a corridor access to Raqqa. It is unclear until now if the Trump administration is willing to completely give up its coordination with the SDF. In addition, the option of having Turkish-backed Arab forces fighting alongside the SDF is unlikely since both Turkey and the SDF reject such a proposal. Turkey will not participate in the battle if the other party includes PYD forces.

Third Scenario

The Americans and Russians would reach an agreement on the framework of a solution in Syria. This would include neutralizing Turkey and enabling the participation of regime forces alongside the YPG. This scenario would be welcomed by the regime. This scenario could become more likely because of the regime’s advances in eastern rural Aleppo reaching the administrative border of Raqqa Province (Ithraya-Khanaser). The regime has also reinforced its presence in Ithraya on the way to Tabqa, as well as in Palmyra, which is a critical position on the road between Palmyra and Raqqa. The regime has also been making attempts to increase its control of more positions in the desert by attacking “Usood al Sharqiyeh” forces in recent days.([27]) The regime also controls critical positions in Deir Ezzor, especially in the western rural areas congruent with Raqqa Province. This includes the Deir Ezzor Military Airport in the eastern part of the province, which extends to the Iraqi border. Thus, the regime puts the Coalition in a position where it has no choice but to coordinate with regime forces, either in the battle for Raqqa or in future operations.

Fourth Scenario

The results of the last Astana meeting to create four de-conflicted zones could be a premise for a fourth scenario in which the U.S. is more open to the participation of all interested parties from Astana in the battle for Raqqa and what comes after. This would include roles for the SDF, regime forces, and opposition forces backed by Turkey. American and Russian oversight would ensure effective implementation of the participating forces and prevent any infighting among them. The de-confliction zones proposal is the strongest evidence that such a scenario may be carried out. The de-confliction zones would essentially mean a truce between regime and opposition forces with well-defined borders in order for the parties to focus their efforts more closely on fighting ISIS. Turkey and Russia responded positively to the last Astana meeting, which followed a meeting between the presidents of Turkey and Russia, indicating that there are some preexisting agreements about Turkey’s participation in the battle for Raqqa. Furthermore, the American approval of the de-confliction zones indicates a possible three-way understanding about the battle for Raqqa. Another positive development is Russia’s reopening lines of communication with the U.S. regarding sharing and coordinating Syria’s air space. This was surprising given the deadly strikes on the Sheirat air base. Further clarification on this possible three-way understanding on the battle for Raqqa is expected following the meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Washington, D.C. on [insert date].

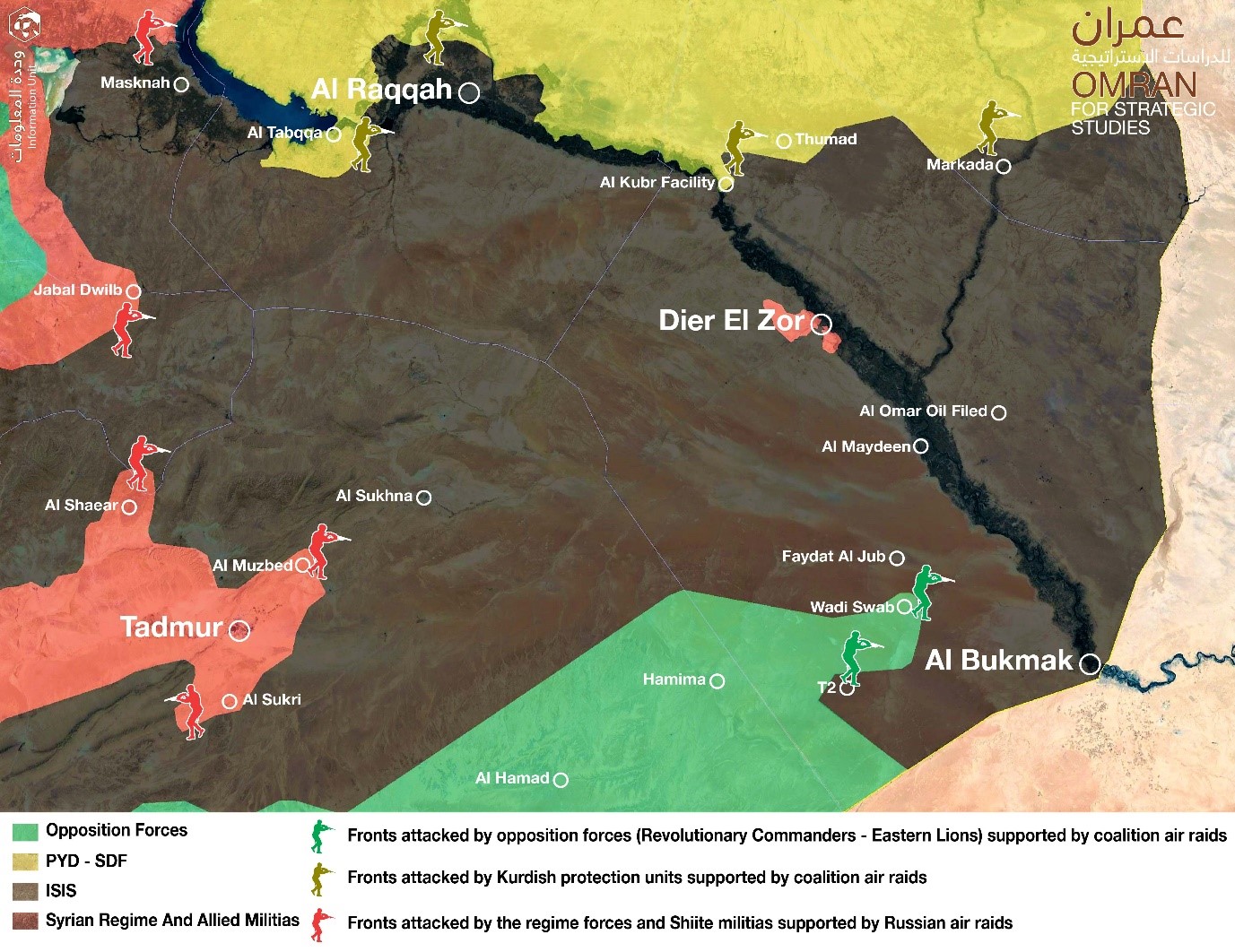

Map No. (2) Control and Influence of Eastern Syria – May 7, 2017

Conclusion

The presence of American forces in Syria joining the fight against ISIS is a significant change in the Syrian arena, making the situation more complicated and the interests of the various parties more contradictory. In the meantime, the U.S. continues to take advantage of these contradictory interests. Therefore, the most important contribution of the American entry into Syria was undermining the post-Aleppo status quo established by Russia in an attempt to create a new climate that is more consistent with an American policy that is more involved in the Middle East. These new understandings are still unclear and will not be completely understood until after the defeat of ISIS. The battle for Raqqa and what comes after are the apex of these understandings, especially the shape of a future Syria that regional and international actors will decide.

([1]) Front lines defenses were shored up at the eastern edge of Operation Euphrates Shield territory with regime, Russian, and US forces creating a buffer preventing any further Turkish backed offensive.

([3]) Fabrince Balance, The Battle for al-Bab Is Bringing U.S.-Turkish Tensions to a Head, The Washington Institute, 2017, https://goo.gl/Q5zGrg

([4]) Turkey announces the end of Operation Euphrates Shield, Arabic, Aljazeera Net, https://goo.gl/JvGtqT

([5]) “Eastern Shield Army”, A new formation to face three powers in Syria’s east, Enab Baladi News, Arabic, https://goo.gl/y4zVWx

([6]) Turkey’s plans to liberate Syria’s Raqqa, Turkey Now, Arabic, https://goo.gl/cmJr9X

([7]) American, Russian, Turkish coordination in Syria, Arabic, Aljazeera Net, https://goo.gl/O7cAC6

([8]) Moscow offers coordination with America in Syria, Al Hayat, https://goo.gl/mDCKb1

([9]) Front lines defenses were shored up at the eastern edge of Operation Euphrates Shield territory with regime, Russian, and US forces creating a buffer preventing any further Turkish backed offensive.

([10]) Safinaz Muhammad Ahmad, “Manbij and Raqqa..International and regional interventions and the new maps of influence in Syria”, Al Ahram for Strategic Studies, https://goo.gl/PyVtoS

([11]) Ibrahim Humeidi, Moscow’s surprise between Manbij and al Bab: Tempting Washington and marginalizing Ankara, Al Hayat, https://goo.gl/VnGkKn

([12]) Larijani: US intervention in Syria is not in its favor .. The presence of the Marines was not in coordination with Tehran .. We do not aim to achieve special interests in Syria, Rai Al Youm, https://goo.gl/PRk0SA

([15]) "Marines" in Syria to accelerate the battle of Raqqa ... and "reassure" Turkey, Al Hayat, https://goo.gl/UELPQg

([17]) PKK is the Kurdistan Workers Party

([18]) After abandoning Obama's plan .. Trump is looking for his way to Raqqa, Russia Today Arabic, https://goo.gl/jvyX8p

([19]) The fourth phase of “Wrath of the Euphrates”: Trying to reach Raqqa’s border, The New Arab, https://goo.gl/JTHxLS

([20]) Daesh withdraws from Tabqa under agreement with SDF, The New Arab, https://goo.gl/3cZcD3

([21]) Raqqa, Between Coalition massacres and preparing for what is after Daesh, Enab Baladi, https://goo.gl/OiQTJ0

([22]) A new massacre by the international coalition in Mansoura in rural Raqqa, Zaman Alwasl, https://goo.gl/6VUbGZ

([23]) The international coalition commits a massacre in Tabqa, Raqqa Post, https://goo.gl/pp2wLv

([25]) Trump gives the Pentagon the power to determine troop levels in Iraq and Syria, Reuters, https://goo.gl/7Er9oO

([26]) Front lines defenses were shored up at the eastern edge of Operation Euphrates Shield territory with regime, Russian, and US forces creating a buffer preventing any further Turkish backed offensive.

([27]) Lions of the East: The regime advances in rural eastern Sweida, MicroSyria, https://goo.gl/zB8cIV

What’s Next for the Opposition After Aleppo

Abstract: The fall of Aleppo is not the end of the opposition in Syria, but perhaps marks the beginning of a Russian attempt to consolidate spheres of influence that are controlled by its regional allies and then push for a political track within its interpretation of political transition. What all actors understand is that it is no longer an option to return to the conditions prior to 2011. The Syrian opposition and its allies still have important cards to play including the empowerment of Local Administration Councils that gain legitimacy from the electorate and able to conduct stabilization programs that are essential during the transition. The opposition still control key strategic locations that should be empowered or a managed cease fire should be implemented to stop the misbalancing of powers.

The Syrian uprising has witnessed several phases each with different features and challenges. They ranged from the non-violent resistance phase, to the militarization, to the spread of cross-border ideological radical groups, to the internationalization of the conflict, the Russian intervention, and finally the consolidation of spheres of influence and control. Political negotiations can be characterized to have gone through phases beginning with the Geneva Communique in 2012, which calls for the formation of a transitional governing body with full executive powers, then the Geneva I, II, and II talks took place starting January 2014 until 2016 where negotiation rounds were stalled every time because of the insistence of the Assad regime to frame the talks for fighting terrorism and not the formation of a transitional governing body with full executive powers. Towards the end of 2015 and throughout 2016, there were a series of meetings called for by Russia and the United States in Vienna and other European capitals where a new international group was formed called the International Syria Support Group (ISSG) that called for a cessation of hostilities as a first step to re-start political negotiations with four main tracks: Humanitarian, Security, Refugee Resettlement, and civil society. A joint commission was formed by Russia and the US to oversee the cessation of hostilities process and the cease-fire agreements. During this process the United Nations Security Council approved the Russia-US agreement in the ISSG and issued UNSC Resolution 2254 calling for political negotiations with a strict timeline, where a cease fire takes place and ISIS and Jabhat Nusra will be targeted, political negotiations to reach a transitional body that ratifies a new constitution and holds elections to inaugurate a political transition. So far the UNSC 2254 has not been on schedule and that brings us to the last phase where Russia, Iran and Turkey met in

December 2016 and issued the Moscow Declaration. The agreement comes after the fall of Aleppo and puts out a more serious attempt to push a political transition process.

This expert brief argues that the fall of Aleppo was a result of a systematic policy by Russia to consolidate territories under the regime control, the Euphrates Shield zone, the Southern Front, the Kurdish controlled zones, then propose a political track according to its interpretation of “political transition”. In the face of the Russian policy, there was no other well-planned policy, underpinned by necessary means, implemented by other local, regional or international powers. The role of Iran is limited within the scope of the Russian policy, yet remains critical and strong on the ground, especially in its control of transportation routes to Lebanon. Additionally, the Russian diplomacy is far more aggressive and consistent with a clear determination for a political track without a regime change paradigm.

For Syrian opposition groups, the fall of Aleppo also puts forward a set of critical challenges and offers fewer options for diplomatic maneuvering while maintaining the balance of power through a freezing of hostilities or a nationwide cease-fire that freezes spheres of influence and control thus creating ground for negotiations. The Syrian opposition should adapt to the new conditions by generating new tools and mechanisms to deal with the new phase. Supporters of the Syrian opposition should also create conditions where Syrian “agency” and local actors are involved in the peace-making and stabilization process from the bottom-up.

The fall of Aleppo was a coordinated effort allegedly aiming at creating new conditions for a political track to be approached according to the Russian terms. This effort can be characterized by the following features:

1. A consistent marginalization of societal demands and aspirations while prioritizing a security based approach at any price, including forced evacuations of residents in Aleppo as well as Daraya, Zabadani and other regions. Local agency is often ignored and assumed to be a “proxy” to outside forces. This is why Russia has attempted to create a “Moscow 1 Syrian opposition”([1]) and “Homaimim opposition”([2]) to legitimize a “political track”; while realizing these groups’ inability to represent relevant Syrian actors in control of territories and borders.

2. The priority of the regime and its allies was to re-gain control of Aleppo at any price while postponing efforts to fight ISIS in order to freeze zones of influence and presumably reach a political agreement that would then focus on fighting ISIS and Jabhat Fath al-Sham. This explains the minimal reaction by the regime and Russia to ISIS re-capturing Palmyra.

3. The “Grozny” approach([3]) during the latest military operation to regain Aleppo after over two years of failed attempts by the Assad regime ends a phase that was featured by the maintenance of the balance of power approach in the management of the conflict. While it was clear the opposition failed to present governance solutions to address security threats, the current scenario puts excessive political and military pressure on the opposition to offer concessions and agree to a Russian framed political track. This will lead to further radicalization and for increased recruitment by terrorist groups who manipulate a victimized narrative.

Additionally, this will lead to further chaos and fragmentation of opposition held areas making it incapable of implementing any transitional programs.

Opposition’s options

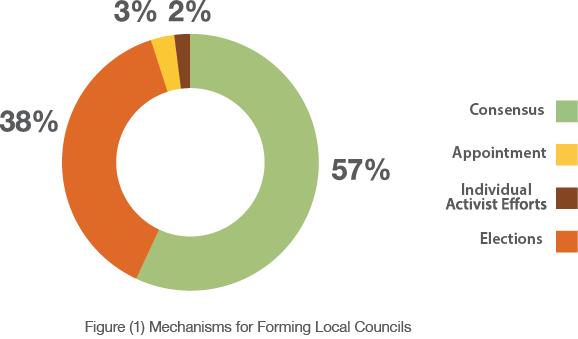

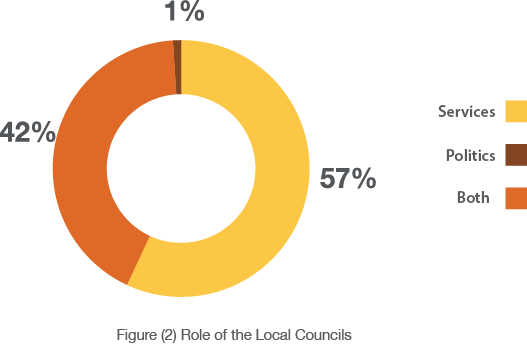

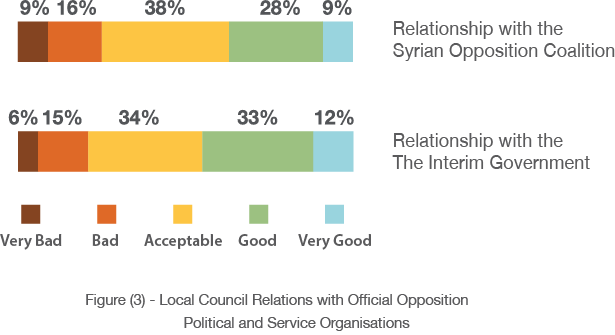

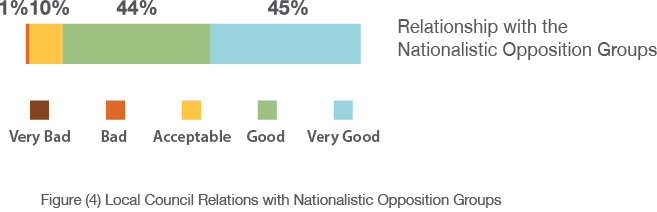

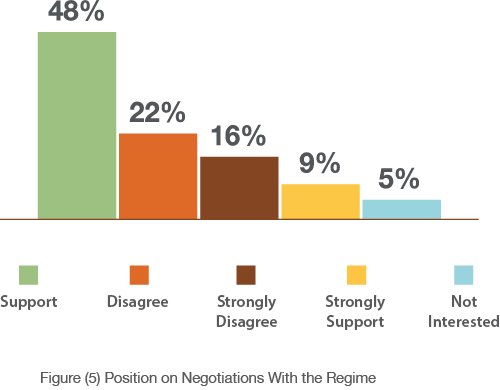

The opposition choices are very limited. They need to be empowered to exercise self-criticism and review its positions and strategies of addressing the political track, including not falling in haphazard mergers between armed groups without a clear agreement on roles and responsibilities as well as relationships with local societal actors. It is of strategic importance now more than ever to empower Local Administration Council that are the only representative bodies in Syria today, as they are structured from the bottom up([4]). Field research shows a high positive correlation between citizen involvement and participation in local councils and the ousting of terrorist groups([5]). Moreover, Local Councils are service providers with clear political roles in representing citizens’ views and limit the control and influence of armed groups. Stabilization programs should rely on local councils and civil society organization more than on armed groups.

The recapture of Aleppo by militias allied with Bashar Assad was not possible without the air support of the Russian Air Force. The forces allied with the regime are very fragmented and disorganized that they could not alone recapture the city of Aleppo([6]). There were several attempts during the past 12 months to recapture the city but none was successful precisely because the Russians had different calculations and did not trust the ability of ground troops to take full control. The amount of military warfare waged on Aleppo was unprecedented and excessive, thus indicating a difficult front they were unable to previously capture without its full destruction and evacuation of all its citizens. The Assad regime remains very fragmented and does not have a monopoly to the “use of force” anymore thus suffering from diminished legitimacy. Information from the ground indicate that the Aleppo operation was fully managed by Russian and Iranian officers, while marginalizing Syrian-regime militias from decision making circles([7]).

Assad in fact has regained a city of rubble devoid of its native population. This poses important questions regarding the upcoming negotiations processes and the place of the evacuated residents in it. Great uncertainty covers the refugees return before the start of any political process, hence affecting the legitimacy of the process. Indeed, Aleppo was strategically very important to the opposition, but it is not the end of the struggle. The opposition is still in control of most borders, major transportation routes, the Southern Front, Euphrates Shield zone, and Idlib. Numbers of armed forces in opposition areas are not to be taken lightly.

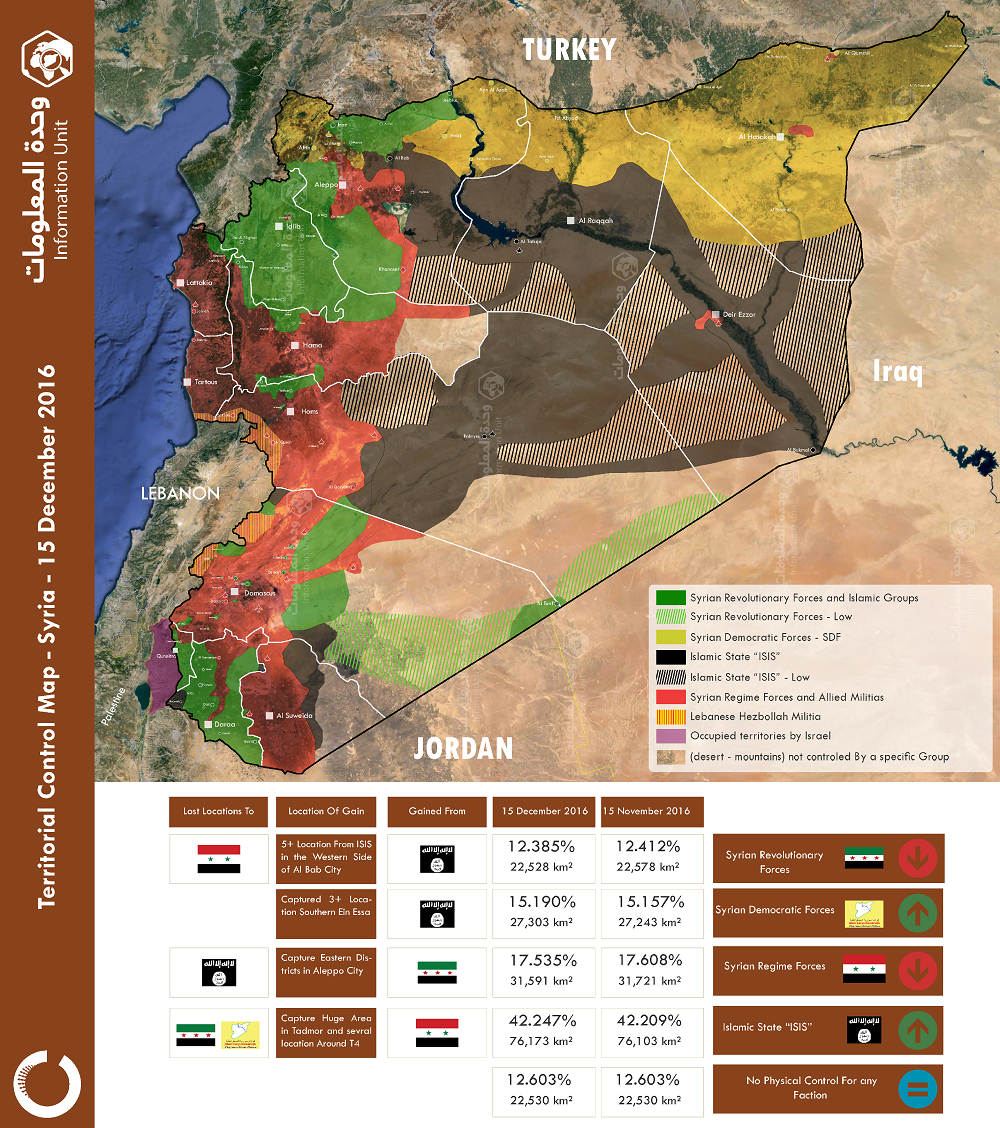

Territorial Control Map - Syria - 15 DEC 2016, No (1)

Another element to be considered is the new evolving Turkish role that focused on securing its borders and national security through the Euphrates Shield operations that are now close to Al-Bab. These forces draw the limits of Turkish military options to the objective of fighting ISIS and ending any possibility of PYD connecting the area between its Kobane and Afrin cantons, hence creating a territorially contiguous Kurdish enclave along Turkey’s borders. While Aleppo has historic, political and economic significance to Turkey, the Turkish role shifted to become a mediator to help create a ceasefire agreement and support on humanitarian efforts. Perhaps the best scenario is a controlled and consolidated territory in the north of Syria where no foreign fighters or other radical Islamist fighters can operate. This serves the objective of stabilizing the conflict and providing new options for a political settlement. This also requires an empowerment of local councils in these zones that provide local services and empowering civilians against militants which seeds for democratic values and institutions.

The Moscow Declaration and the Challenges Ahead

The Moscow Declaration established a new set of expectations by actors who are present on the ground as compared to previous attempts by a larger setting such as in Vienna and Geneva. The Declaration also increases the importance of creating a platform for Syrian opposition groups to avoid previous mistakes and consolidate their bodies and decision-making processes. The new phase requires different diplomatic and military tools and mechanisms; and the current Syrian opposition structures and negotiation strategies fall short of meeting the challenges of the current phase.

The moment also requires a plan to deal with Jabhat Fath al-Sham (previously known as Nusra Front). Syrian groups should end all communications and coordination with this group, and work to push them out of inhabited areas of Idlib. This could be done by highlighting the role of representative local councils as the civilians “horses for peace”, while pushing the militias to be regulated under the new civilian administration in order to deliver security. Holding elections as means to re-establish localized governance is a stepping-stone to stabilization programs. This also requires the limiting of armed groups interferences in public life and the provision of public services. The model presented by the Euphrates Shield in re-organizing Free Syrian Army groups, professionalizing them, and limiting their mandate to fighting terrorism can be adopted at least temporally. These programs should not wait a political track. It should serve the purpose of consolidating opposition areas, countering terrorism, and re-establishing order and rule of law. This will empower the opposition to be better equipped as a “state” not as “opposition” to enter negotiations as a reliable partner. Many claim this is unrealistic, but I claim that a political will and a paradigm shift by opposition groups, local councils, and armed groups can make this a reality.

For a sustainable peace plan to be maintained, all relevant actors on the ground should be involved and not treated as a “proxy” with countries “guaranteeing” positions on their behalf. Assuming that a resolution could be reached by forming a government with members from different “sides” of the conflict overlooks the true societal nature of the uprising and assumes that citizens can go back to the former rules of governance and the former forged social contract. A new social pact based on decentralization of governance and administration should be agreed upon by Syrians. This means all foreign fighters beginning with the 41 militias([8]) supported by Iran including Hezbollah and their re-located foreign families should leave Syria. This requires a systematic process and a full plan that does not only rely on hard power and use of force. Syrian actors should be empowered to take responsibility of their local cities and towns and not allow them to operate freely. Additionally, the fight against ISIS and al-Qaeda affiliates cannot be won without a unified Syria, an end of the current system of governance, a new military-security philosophy, and the exit of Shia militias that reinforce the ISIS narrative and increase its recruitment world-wide. The presence of these terrorist militias is the main reason for the imbalance of power in Syria that lead among other reasons to the spread of ISIS.

It is not over yet. The opposition still hold several important cards that should be wisely maintained for the best of all parties. There still remains strongholds for the Syrian opposition that require careful negotiations to ensure that it is not lost and does not undergo a similar fate to that of Aleppo, by including them in a nation-wide ceasefire and implementing an agreement for a weapon-free zone with Russian guarantees. These areas including the Eastern Ghouta in Damascus Suburbs, and Idlib as a center for refugee resettlement and economic reconstruction. The liberation of Raqqa will also determine the trajectory of the conflict and the nascent control zones, refugee outflow policies and programs, and counter-terrorism programs. All the forgone are potential cooperation issues between the foreign stakeholders and the Syrian opposition in order to reverse the vicious cycle of conflict.

The conflict in Syria will not end with fall of Aleppo and the new round of political talks unless relevant actors “local agency” is involved and have a buy-in to the transition plan. Local actors include Local Councils and influential figures and civil society groups. The political process cannot proceed without applying the same rule to all sides of the conflict; the exit of all foreign fighters. The weakest element in the equation is the Asad regime that has been deeply fragmented with multiple militias and loyalties within its composition thus making it incapable of fulfilling any agreement they sign on to, without guarantees by Russia and Iran. A true transition plan should address the demands of the local citizens and establish a new beginning for the reconstruction of Syria.

Published In ALSharq Forum, 29/12/ 2016: https://goo.gl/ecsOjf

([1]) The Russian Foreign Ministry hosted Moscow 1 and 2 meetings and invited opposition figures such as former government official Kadri Jamil, with the purpose of creating a legitimate body to take part in political negotiations but with demands limited to democratic changes in government to include more people rather than demands held by protestors. This group can be characterized as a group of individuals with little ties to relevant actors on the ground. This group alone cannot implement a peace truce but were brought to dilute the positions of the “opposition” and show a Russia-aligned group that could be a partner in the future.

([2]) Homaimim Russian base in Syria has been a hub hosted by the Russian Defense Department to bring together Syrian “opposition” that live in regime held areas and create “shell” bodies that represent their limited demand for inclusion and diversity while being more aligned with the Russian narrative of the conflict. These members represent primarily interest groups that are linked with the regime and not any actor that has the power to implement or “sell” an agreement with relevant actors on the ground.

([3]) In 1994-1995, Russian forces invaded the city of Grozny to stop the armed uprising and use lethal force and all destructive tools. Many refer to Grozny as it seemed a policy being implemented in the recapture of Aleppo where the eastern city was fully destroyed without any distinction of those being attacked and using all type of weaponry.

([4]) In the survey conducted by the Local Administration Council’s Unit (LACU) and Omran for Strategic Studies in Summer of 2015, 405 local councils were interviewed and asked about their governance structures. This number reflects those councils we were able to reach, but represents 90% of local councils in operation. About one-third of these interviewed say councils’ members are voted by local constituency and two-thirds by local consensus of local actors and civil society. These Councils are tasked with provision of basic services to local residents, including local governance, permits for NGO’s operation, public infrastructures, local safety, rescue services (White Helmets was started by Local Councils), education, and health services.

([5]) An example could be seen in the Southern Front where there are 76 local councils on the city and village level and the agreement between local councils and armed opposition groups allowed for Nosra to have little if any existence in areas governed by local councils. Another similar example is perhaps, Daraya (Damascus Suburb), and Maarat Noman (Idlib).

([6]) Omran for Strategic Studies Information Unit researchers in Aleppo reported large number of fighters pouring into the military fronts from al-Nujaba Shiaa Militia, and that the ground control command was with Iranian militias with minimal official Syrian Army presence. Also see: http://edition.cnn.com/2016/12/12/middleeast/syria-analysis-tim-lister/

([7]) Personal interview (Mohamad from Homs originally, does not wish to be named) with defected soldier who was stationed in Al-Qusair after its fall, then stationed in Deir Azzour before defecting, interview date August 25, 2016. He revealed that in military operation rooms where Hezbollah officers preceded, they did not allow Alawite Syrian officers to stay in the room during operational planning, and also forced them to taste food cooked before Hezbolla officers eat.

([8]) Omran for Strategic Studies Information Unit map of foreign militias allied with the regime including numbers and training locations, unpublished, dated Nov 25, 2016.

TRT World Interview with Ammar Kahf about on the latest in Aleppo

Dr. Ammar Kahf Talks about on the latest in Aleppo

TRT World Interview with Ammar Kahf about cessation deal reached by US and Russia

Dr. Ammar Kahf Talks about cessation deal reached by US and Russia

Geopolitical Realignments around Syria: Threats and Opportunities

Abstract: The Syrian uprising took the regional powers by surprise and was able to disrupt the regional balance of power to such an extent that the Syrian file has become a more internationalized matter than a regional one. Syria has become a fluid scene with multiple spheres of influence by countries, extremist groups, and non-state actors. The long-term goal of re-establishing peace and stability can be achieved by taking strategic steps in empowering local administration councils to gain legitimacy and provide public services including security.

Introduction

Regional and international alliances in the Middle East have shifted significantly because of the popular uprisings during the past five years. Moreover, the Syrian case is unique and complex whereby international relations theories fall short of explaining or predicting a trajectory or how relevant actors’ attitudes will shift towards the political or military tracks. Syria is at the center of a very fluid and changing multipolar international system that the region has not witnessed since the formation of colonial states over a century ago.

In addition to the resurrection of transnational movements and the increasing security threat to the sovereignty of neighboring states, new dynamics on the internal front have emerged out of the conflict. This commentary will assess opportunities and threats of the evolving alignments and provide an overview of these new dynamics with its impact on the regional balance of power.

The Construction of a Narrative

Since March 2011, the Syrian uprising has evolved through multiple phases. The first was the non-violent protests phase demanding political reforms that was responded to with brutal use of force by government security and military forces. This phase lasted for less than one year as many soldiers defected and many civilians took arms to defend their families and villages. The second phase witnessed further militarization of civilians who decided to carry arms and fight back against the aggression of regime forces towards civilian populations. During these two phases, regional countries underestimated the security risks of a spillover of violence across borders and its impact on the regional balance of power. Diplomatic action focused on containing the crisis and pressuring the regime to comply with the demands of the protestors, freeing of prisoners, and amending the constitution and several security based laws.

On the other hand, the Assad regime attempted to frame a narrative about the uprising as an “Islamist” attempt to spread terrorism, chaos and destruction to the region. Early statements and actions by the regime further emphasized a constructed notion of the uprising as a plot against stability. The regime took several steps to create the necessary dynamics for transnational radical groups (both religious and ethnic based) to expand and gain power. Domestically, it isolated certain parts of Syria, especially the countryside, away from its core interest of control and created pockets overwhelmed by administrative and security chaos within the geography of Syria where there is a “controlled anarchy”. It also amended the constitution in 2012 with minor changes, granted the Kurds citizenship rights, abolished the State Security Court system but established a special terrorism court that was used for protesters and activists. The framing of all anti-regime forces into one category as terrorists was one of the early strategies used by the regime that went unnoticed by regional and international actors. At the same time, in 2011 the regime pardoned extremist prisoners and released over 1200 Kurdish prisoners most of whom were PKK figures and leaders. Many of those released later took part in the formation of Jabhat al-Nusra, ISIS, and YPG forces respectively. This provided a vacuum of power in many regions, encouraging extremist groups to occupy these areas thus laying the legal grounds for excessive use of force in the fight against terrorism.

The third phase witnessed a higher degree of military confrontations and a quick “collapse” of the regime’s control of over 60% of Syrian territory in favor of revolutionary and opposition forces. Residents in 14 provinces established over 900 Local Administration Councils between 2012 and2013. These Councils received their mandate and legitimacy by the consensus or election of local residents and were tasked with local governance and the administration of public services. First, the Syrian National Council, then later the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces were established as the official representative of the Syrian people according to the Friends of Syria group. The regime resorted to heavy shelling, barrel bombing and even chemical weapons to keep areas outside of its control in a state of chaos and instability. This in return escalated the level of support for revolutionary forces to defend themselves and maintain the balance of power but not to expand further or end the regime totally.

During this phase, the internal fronts witnessed many victories against regime forces that was not equally reflected on the political progress of the Syria file internationally. International investment and interference in the Syrian uprising increased significantly on the political, military and humanitarian levels. It was evident that the breakdown of the Syrian regime during this phase would threaten the status quo of the international balance of power scheme that has been contained through a complex set of relations. International diplomacy used soft power as well as proxy actors to counter potential threats posed by the shifting of power in Syria. Extremist forces such as Jabhat al-Nusra, YPG and ISIS had not yet gained momentum or consolidated territories during this phase. The strategy used during this phase by international actors was to contain the instability and security risk within the borders and prevent a regional conflict spill over, as well as prevent the victory of any internal actor. This strategy is evident in the UN Security Council Resolution 2042 in April 2012, followed by UNSCR 2043, which call for sending in international observers, and ending with the Geneva Communique of June 2012. The Geneva Communique had the least support from regional and international actors and Syrian actors were not invited to that meeting. It can be said that the heightened level of competition between regional and international actors during this phase negatively affected the overall scene and created a vacuum of authority that was further exploited by ISIS and YPG forces to establish their dream states respectively and threaten regional countries’ security.

The fourth phase began after the chemical attack by the regime in August of 2013 where 1,429 victims died in Eastern Damascus. This phase can be characterized as a retreat by revolutionary military forces and an expansion and rise of transnational extremist groups. The event of the chemical attack was a very pivotal moment politically because it sent a strong message from the international actors to the regional actors as well as Syrian actors that the previous victories by revolutionary forces could not be tolerated as they threatened the balance of power. Diplomatic talks resulted in the Russian-US agreement whereby the regime signed the international agreement and handed over its chemical weapons through an internationally administered process. This event was pivotal as it signified a shift on the part of the US away from its “Red Line” in favor of the Russian-Iranian alignment, which perhaps was their first public assertion of hegemony over Syria. The Russian move prevented the regime’s collapse and removed the possibility of any direct military intervention by the United States. It is at this point that regional actors such as Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia began to strongly promote a no-fly zone or a ‘safe zone’ for Syrians in the North of Syria. During this time, international actors pushed for the first round of the Geneva talks in January 2014, thus giving the Assad regime the chance to regain its international legitimacy. Iran increased its military support to all of Hezbollah and over 13 sectarian militias that entered Syria with the objective of regaining strategic locations from the opposition.

The lack of action by the international community towards the unprecedented atrocities committed by the Syrian regime, along with the administrative and military instability in liberated areas created the atmosphere for cross-border terrorist groups to increase their mobilization levels and enter the scene as influential actors. ISIS began gaining momentum and took control over Raqqa and Deir Azzour, parts of Hasaka, and Iraq. On September 10, 2014, President Obama announced the formation of a broad international coalition to fight ISIS. Russia waited on the US-led coalition for one year before announcing its alliance to fight terrorism known as 4+1 (Russia, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Hezbollah) in September 2015. The Russian announcement came at the same time as ground troops and systematic air operations were being conducted by the Russian armed forces in Syria. In December 2015, Saudi Arabia announced the formation of an “Islamic Coalition” of 34 largely Muslim nations to fight terrorism, though not limited to ISIS.

These international coalitions to fight terrorism further emphasized the narrative of the Syrian uprising which was limited to countering terrorism regardless of the internal outlook of the agency yet again confirming the regime’s original claims. As a result, the Syrian regime became the de facto partner in the war against terrorism by its allies while supporters of the uprising showed a weak response. The international involvement at this stage focused on how to control the spread of ISIS and protect each actor from the spillover effects. The threat of terrorism coupled with the massive refugee influx into Europe and other parts of the world increased the threat levels in those states, especially after the attacks in the US, France, Turkey and others. Furthermore, the PYD-YPG present a unique case in which they receive military support from the United States and its regional allies, as well as coordinate and receive support from Russia and the regime, while at the same time posing a serious risk to Turkey’s national security. Another conflictual alliance is that of Baghdad; it is an ally of Iran, Russia and the Syrian regime; but it also coordinates with the United States army and intelligence agencies.

The allies of the Assad regime further consolidated their support of the regime and framing the conflict as one against terrorism, used the refugee issue as a tool to pressure neighboring countries who supported the uprising. On the other hand, the United States showed a lack of interest in the region while placing a veto on supporting revolutionary forces with what was needed to win the war or even defend themselves. The regional powers had a small margin between the two camps of providing support and increasing the leverage they have on the situation inside Syria in order to prevent themselves from being a target of such terrorism threats of the pro-Iran militias as well as ISIS.

In Summary, the international community has systematically failed to address the root causes of the conflict but instead concentrated its efforts on the conflict's aftermath. By doing so, not only has it failed to bring an end to the ongoing conflict in Syria, it has also succeeded in creating a propitious environment for the creation of multiple social and political clashes, hence aggravating the situation furthermore. The different approaches adopted by both the global and regional powers have miserably failed in re-establishing balance and order in the region. By insisting on assuming a conflictual stance rather than cooperating in assisting the vast majority of the Syrian people in the creation of a new balanced regional order, they have assisted the marginalized powers in creating a perpetual conflict zone for years to come.

Security Priorities

The security priorities of regional and international actors have been in a realignment process, and the aspirations of regional hegemony between Turkey, Arab Gulf states, Iran, Russia and the United States are at odds. This could be further detailed as follows:

• The United States: Washington’s actions are essentially a set of convictions and reactions that do not live up to its foreign policy frameworks. The “fighting terrorism” paradigm has further rooted the “results rather than causes” approach, by sidelining proactive initiatives and instead focusing on fighting ISIS with a tactical strategy rather than a comprehensive security strategy in the region.

• Russia: By prioritizing the fight against terror in the Levant, Moscow gained considerable leverage to elevate the Russian influence in the Arab region and an access to the Mediterranean after a series of strategic losses in the Arab region and Ukraine. Russia is also suffering from an exacerbating economic crisis. Through its Syria intervention, Russia achieved three key objectives:

1. Limit the aspirations and choices of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey in the new regional order.

2. Force the Iranians to redraft their policies based on mutual cooperation after its long control of the economic, military and political management of the Assad regime.

3. Encourage Assad’s allies to rally behind Russia to draft a regional plan under Moscow’s leadership and sphere of influence.

• Iran: Regionally, Iran intersects with Washington and Moscow’s prioritizing of fighting terrorism over dealing with other chronic political crises in the region. It is investing in fighting terrorism as a key approach to interference in the Levant. The nuclear deal with Iran emerged as an opportunity to assign Tehran as the “regional police”, serving its purpose of exclusively fighting ISIS. The direct Russian intervention in Syria resulted in Iran backing off from day-to-day management of the Syrian regime’s affairs. However, it still maintains a strong presence in most of the regional issues – allowing it to further its meddling in regional security.

• Turkey: Ankara is facing tough choices after the Russian intervention, especially with the absence of US political backing to any solid Turkish action in the Levant. It has to work towards a relative balance through small margins for action, until a game changer takes effect. Until then, Turkey’s options are limited to pursuing political and military support of the opposition, avoiding direct confrontation with Russia and increasing coordination with Saudi Arabia to create international alternatives to the Russian-Iranian endeavors in the Levant. Turkey’s options are further constrained by the rise of YPG/PKK forces as a real security risk that requires full attention.

• Saudi Arabia: The direct Russian intervention jeopardizes the GCC countries’ security while it enhances the Iranian influence in the region, giving it a free hand to meddle in the security of its Arab neighbors. With a lack of interest from Washington and the priority of fighting terror in the Levant, the GCC countries are only left with showing further aggression in the face of these security threats either alone or with various regional partnerships, despite US wishes. One example is the case in Yemen, where they supported the legitimate government. Most recently in Lebanon, it cut its financial aid and designated Hezbollah as a terrorist organization. Riyadh is still facing challenges of maintaining Gulf and Arab unity and preventing the plight of a long and exhausting war.

• Egypt: Sisi is expanding Egyptian outreach beyond the Gulf region, by coordinating with Russia which shares Cairo’s vision against popular uprisings in the Arab region. He also tries to revive the lost Egyptian influence in Africa, seeking economic opportunities needed by the deteriorating Egyptian economic infrastructure.

• Jordan: It aligns its priorities with the US and Russia in fighting terrorism, despite the priorities of its regional allies. Jordan suffices with maintaining security to its southern border and maintaining its interests through participating in the so-called “Military Operation Center - MOC”. It also participates and coordinates with the US-led coalition against terrorism.

• Israel: The Israeli strategy towards Syria is crucial to its security policy with indirect interventions to improve the scenarios that are most convenient for Israel. Israel exploits the fluidity and fragility of the Syrian scene to weaken Iran and Hezbollah and exhaust all regional and local actors in Syria. It works towards a sectarian or ethnic political environment that will produce a future system that is incapable of functioning and posing a threat to any of its neighbors.

During the recent Organization of Islamic Cooperation conference in Istanbul the Turkish leadership criticized Iran in a significant move away from the previous admiration of that country but did not go so far as cutting off ties. One has to recognize that political realignments are fluid and fast changing in the same manner that the “black box” of Syria has contradictions and fragile elements within it. The new Middle East signifies a transitional period that will witness new alignments formulated on the terrorism and refugee paradigms mentioned above. Turkey needs Iran’s help in preventing the formation of a Kurdish state in Syria, while Iran needs Turkey for access to trade routes to Europe. The rapprochement between Turkey and the United Arab Emirates as well as other Gulf States signifies a move by Turkey to diffuse and isolate polarization resulting from differences on Egypt and Libya and building a common ground to counter the security threats.

Opportunities and Policy Alternatives

The political track outlined in UNSC 2254 has been in place and moving on a timeline set by the agreements of the ISSG group. The political negotiations aim to resolve the conflict from very limited angles that focus on counter terrorism, a permanent cease-fire, and the maintenance of the status quo in terms of power sharing among the different groups. This political track does not resolve the deeper problems that have caused instability and the regional security threat spillover. This track does not fulfill the security objectives sought by Syrian actors as well as regional countries.

Given the evolving set of regional alignments that has struck the region, it is important to assess alternative and parallel policies to remain an active and effective actor. It is essential to look at domestic stabilizing mechanisms and spheres of influence within Syria that minimize the security and terrorism risks and restore state functions in regions outside of government control. Local Administration Councils (LAC) are bodies that base their legitimacy on the processes of election and consensus building in most regions in Syria. This legitimacy requires further action by countries to increase their balance of power in the face of the threat of terrorism and outflow of refugees.

A major priority now for regional power is to re-establish order and stability on the local level in terms of developing a new legitimacy based on the consensus of the people and on its ability to provide basic services to the local population. The current political track outlined by the UNSC 2254 and the US/Russian fragile agreements can at best freeze the conflict and consolidate spheres of influence that could lead to Syria’s partition as a reality on the ground. The best scenario for regional actors at this point in addition to supporting the political track would be to support and empower local transitional mechanisms that can re-establish peace and stability locally. This can be achieved by supporting and empowering both local administration councils and civil society organizations that have a more flexible work environment to become a soft power for establishing civil peace. Any meaningful stabilization project should begin with the transitioning out of the Assad regime with a clear agreed timetable.

Over 950 Local Councils in Syria were established during 2012-2013, and the overwhelming majority were the result of local electing of governing bodies or the consensus of the majority of residents. According to a field study conducted by Local Administration Councils Unit and Omran Center for Strategic Studies, at least 405 local councils operate in areas under the control of the opposition including 54 city-size councils with a high performance index. These Councils perform many state functions on the local level such as maintaining public infrastructure, local police, civil defense, health and education facilities, and coordinating among local actors including armed groups. On the other hand, Local Councils are faced with many financial and administrative burdens and shortcomings, but have progressed and learned extensively from their mistakes. The coordination levels among local councils have increased lately and the experience of many has matured and played important political roles on the local level.

Regional powers need domestic partners in Syria that operate within the framework of a state institution not as a political organization or an armed group. Local Councils perform essential functions of a state and should be empowered to do that financially but more importantly politically by recognizing their legitimacy and ability to govern and fill the power vacuum. The need to re-establish order and peace through Local Councils is a top priority that will allow any negotiation process the domestic elements of success while achieving strategic security objectives for neighboring countries.

Published In The Insight Turkey, Spring 2016, Vol. 18, No. 2

TRT World -Interview with Dr. Ammar Kahf about safe passages out of Syria