Events

Syria’s Reserve Military Service Transformations and Objectives

Reserve service has been one of the most significant human resource components of the Syrian Regime Army, yet it has also posed one of the greatest challenges and obstacles for Syrians, especially after 2011. This is due to its extended duration([1]), with recruits unable to ascertain the length of their service or their discharge date.

The Turkish-Russian ceasefire agreement of March 2020 and the cessation of major military operations enabled the army to implement changes in reserve service, along with other reforms within the military and security institutions.

From mid-2023 to mid-2024, the leadership of the Army issued several administrative orders to end the retention of certain categories of reserve service personnel([2]). This occurred before the official announcement of a plan for a "professional army", as stated by the Director of the General Administration of the "Army and Armed Forces"([3]).

This article aims to clarify the current plan for reserve service and the objectives the regime seeks to achieve. Additionally, it will highlight the legal aspects related to reserve service and trace the changes made over the past several years.

Reserve Service Plan:Confirmed to Be 2 Years after All

It has become evident over the years that the regime has implemented new measures related to the army, especially after the appointment of a new Minister of Defense in April 2022([4]). The years of military conflict since 2011 have demonstrated to the regime that an army based on conscripts is neither effective nor reliable. The regime’s lack of trust into its own army stems not only from the military's lack of professionalism but also social and sectarian reasons. Consequently, the regime has found it necessary to shift towards building a “professional army” composed of enlisted (volunteer) personnel, starting with a gradual reduction in the duration of reserve service as the first step toward redefining compulsory military service. However, this transition will take several more years to fully realize, ultimately helping to sustain the solid core upon which the regime has relied in its war against people.

The plan to build a “professional army” began with the army leadership introducing consecutive volunteer contracts for five or ten years. These contracts clearly outlined the substantial benefits provided to new enlistees, including higher salaries and additional bonuses. The new enlistees are exempt from compulsory military service if they complete five years of service and could leave the army upon completing the contract, subject to approval from the General Command. Notably, these benefits were not extended to previous enlistees, including in terms of salaries or entitlements([5]).

Additional administrative orders related to reserve service continued to be issued until the reserve service plan was officially announced in June 2024. The plan is based on three main phases, culminating in a defined reserve service duration of 24 months([6]). The plan is structured as follows:

| Discharge Date | Duration of Reserve Service | Note |

| Phase One | ||

| 01/07/2024 | 6 years | Discharged |

| 31/08/2024 | 5.5 years | Discharged on the specified date |

| 31/10/2024 | 5 years | Discharged on the specified date |

| 31/12/2024 | 4.5 years | Discharged on the specified date |

| Number of discharges by end of Phase One | 46,044 military personnel | |

| Phase Two | ||

| 28/02/2025 | 4 years | Discharged after completing 4 years of service by 31/01/2025 |

| 30/04/2025 | 3.5 years | Discharged after completing 3.5 years of service by 28/02/2025 |

| 30/06/2025 | 3 years | Discharged after completing 3 years of service by 31/03/2025 |

| 31/08/2025 | 2.5 years | Discharged after completing 2.5 years of service by 30/04/2025 |

| 31/10/2025 | 2 years | Discharged after completing 2 years of service by 31/05/2025 |

| Total number of military personnel to be discharged by the end of Phase Two | 105,869 | |

| Total number of military personnel to be discharged during Phases One and Two | 151,913 | |

| Phase Three | ||

| 01/01/2026 | 2 years | Discharged after completing 2 years of service |

Table (1): Reserve Service Plan

According to the official announcement, the plan may undergo modifications in the implementation of certain aspects based on the study of reserve service issues, including age criteria and years of service. The time periods for each of the three phases may be adjusted, either increased or decreased, based on the enlistment rates for compulsory military service and the number of contracted enlisted military personnel.

The large number of military personnel, approximately 152,000,expected to be discharged from reserve service by the end of 2025([7]) indicates significant human resources available to the army. This figure does not include those already enlisted or conscripted for compulsory military service at the time the plan was issued, and contradicts previous estimates and reports that indicated a significant personnel shortage in the army([8]).

The plan also includes a clause for the discharge of enlisted military personnel who complete five years of their new recruitment contract (as fighters) and choose not to continue. These individuals will not be retained or called up for reserve service until five years have passed since their discharge. They are also exempt from compulsory military service. However, they may be called up for reserve service for one year only, which can be served continuously or intermittently. Those with ten-year contracts are fully exempt from reserve service upon completion.

Legal Amendments: Serving the Regime's Interests

After the beginning of the Syrian revolution in March 2011, and due to the circumstances imposed by the conflict, the regime made numerous amendments to the Conscription Law (Legislative Decree No. 30 of 2007) to address gaps revealed by the conflict, despite the law having been recently enacted at the time([9]). Among the revised provisions was Article 26, which pertains to exemptions from reserve service. The first change came with Legislative Decree No. 31 of 2020, which added paragraph (e) to Article 26. This amendment allowed for the exemption of individuals residing outside Syria for at least one year upon payment of a cash allowance of USD 5,000."([10]) This amendment aimed to provide additional foreign currency to the Ministry of Defense's treasury.

At the end of 2022, Law No. 29 of 2022([11]) was issued, amending paragraphs (a) and (c) of Article 26. The amendment made paragraph (a) more specific, categorizing disabilities into three types: partial disability not fit for service, near-total disability, and total disability. Paragraph (c) detailed exemptions for only sons and those considered as such due to siblings affected by seven specified disabilities or ailments([12]). This amendment also coincided with the abolition of Decree No. 174 of 2006, which included the “Physical Fitness System for Conscription”([13]). This system had been used to determine whether a conscript could be fully exempted from service or assigned to field or stationary roles based on permanent health conditions.

The regime did not stop at these amendments. On 1 December 2023, it issued Legislative Decree No. 37 of 2023, adding a new paragraph (f) to Article 26([14]). This provision allowed conscripts for reserve service (enrolled or not) who had reached the age of 40 to pay a cash allowance of USD 4,800 or its equivalent in Syrian pounds, with a reduction of USD 200 or its equivalent for each month of service performed by the conscript. This amendment aimed to generate additional funds for the Ministry of Defense’s treasury. Later, in August 2024, the regime issued Legislative Decree No. 20 of 2024, which lowered the eligible age in paragraph (f) from 40 to 38 years([15]).

Additionally, Legislative Decree No. 20 of 2024 introduced two new paragraphs to Article 26. Paragraph (g) stipulated that conscripts could be exempt from reserve service by paying a cash allowance of USD 3,000 if they could prove they have partial disability not fit for service or near-total disability as listed in paragraph (a). This amendment aimed to offer a lower cash allowance for those with less than total disabilities, in line with the regime’s broader policies on disability, as outlined in Legislative Decree No. 19 of 2024([16]). (h) provided an exemption for military personnel who completed ten years of service under the new enlistment contracts mentioned above.

What Lies Behind the Reserve Service Plan?

The reserve service plan aims to alleviate social pressures in regime-controlled areas, especially following significant waves of men leaving the country to seek asylum. seeking to avoid reserve service is one of the factors, along with security or economic or social reasons. Notably, the regime has suspended reserve service for conscripted officers holding university degrees requiring at least five years of study, as well as those holding higher degrees such as a master’s or PhD([17]), regarding to brain drain as many professionals left Syria in order to avoid military service.

This plan is also closely related to the rate of personnel mobilization within the regime forces([18]).New conscripts are being recruited, and discharged personnel are being replaced by enlistees who were attracted through previously announced enlistment contracts. Thus, the plan remains flexible and may be adjusted at various stages, given that the transformation to a "professional army" is still in its early stages and has not yet fully matured.

Another goal of the plan is to make the benefits of enlistment contracts equal to or even better than those offered by contracts in pro-regime militias, marking a significant shift from previous practices. By offering these contracts, the regime aims to integrate militia members into the official military institution as individuals, rather than as distinct groups. This is especially evident in the raised age limit to 32 years, which suggests an effort to weaken militias by drawing their members into the official forces, without necessarily dismantling the militias entirely at least for now.

In some respects, the regime's plan aims to generate additional funds for the Ministry of Defense's treasury and to leverage reserve service as a tool against society to extort it to generate funds and to keep control over the population. The option to pay a cash allowance in lieu of reserve service was not available until 2020, initially only for those outside the country. By the end of 2023, this option was extended to those within the country who meet the age requirement.

The reserve service issue is one of many critical challenges arising from the conflict since 2011, significantly both the military and social spheres across a large segment of Syrians. The regime approaches this issue with caution and deliberation. While reserve service was an important source of human resources for the regime until 2020, it has since evolved into a revenue-gathering tool, with payments collected from conscripts who wish to avoid service and can afford the cash allowance, both inside and outside the country. The regime’s amendments also portray it as a reformist entity, such as showcasing reform efforts in negotiations with external actors, while this approach focus on its own interests, and without regard for the direct or indirect effects of its policies.

Appendix:

Article 26 of the Conscription Law Issued by Legislative Decree No. 30 of 2007 and All Its Amendments.

Original Article of 26([19]):

The Draftee may be exempted from Reserve Service in one of the following cases:

- Permanent lack of physical fitness for Military Service.

- The remaining children of two parents or one parent, whether both or one are living or dead, both or one of whom have had two children die or become martyred as a result of carrying out a work-related duty in the state or as a result of military operations.

- The only son of two parents or a mother, living or dead, who is effectively the only healthy son to a sibling or siblings who have been afflicted with disabilities or ailments which prevent them from caring for themselves.

- A father who has had one or more son die or become martyred as a result of war operations because of carrying out a work-related duty in the state or as a result of military operations recognized in the regulations.

Amended Article of 26([20]):

The Draftee may be exempted from Reserve Service in one of the following cases:

a. Those permanently unable to perform reserve service, as determined by a medical examination, falling into one of the following categories: (partial disability not fit for service; near-total disability; total disability). (Amended by Law No. 29 of 2022).

b. The remaining children of two parents or one parent, whether both or one are living or dead, both or one of whom have had two children die or become martyred as a result of carrying out a work-related duty in the state or as a result of military operations.

c. The only son of two parents or a father or a mother, living or dead, who is effectively the only healthy brother to a sibling or siblings who have been afflicted by one of the seven specified disabilities or ailments. (Amended by Law No. 29 of 2022).

- First:

- Complete kidney failure.

- Severe intellectual disability resulting in profound cognitive impairment.

- Severe schizophrenia and severe postpartum depression.

- Complete paralysis of one side of the body or all four limbs.

- Total blindness with no vision beyond light perception in either eye.

- Amputation of both lower limbs at the level of the legs or thighs.

- Amputation of both upper limbs at or above the wrist joint level.

- Second: Those in similar conditions may be recommended by the permanent medical committees and approved by the military medical council.

d. A father who has had one or more son die or become martyred as a result of war operations because of carrying out a work-related duty in the state or as a result of military operations recognized in the regulations

e. Those residing outside the territory of the Syrian Arab Republic for at least one year upon payment of a cash allowance of five thousand US dollars. (Added by Legislative Decree No. 31 of 2020).

f. Those who pay the cash allowance (enrolled or not) who have reached the age of 38 must pay 4,800 US dollars or its equivalent in Syrian pounds based on the exchange rate set by the Central Bank of Syria on the payment date. A reduction of 200 US dollars, or its equivalent in Syrian pounds based on the exchange rate set by the Central Bank of Syria on the payment date, is applied for each month of service performed by the enrolled conscript, with partial months rounded up. (Added by Legislative Decree No. 37 of 2023. The age limit was initially 40 but was amended to 38 by Legislative Decree No. 20 of 2024).

g. Those who pay the cash allowance (enrolled or not) of three thousand US dollars, or its equivalent in Syrian pounds as per the exchange rate set by the Central Bank of Syria on the payment date, if the medical examination confirms they fall into one of the categories (lower disability - partial disability capable of performing service). (Added by Legislative Decree No. 20 of 2024).

h. Military personnel who have completed ten years of service under the new enlistment contract (as fighters). (Added by Legislative Decree No. 20 of 2024).

([1]) After completing compulsory military service, men remain eligible for reserve call-up until age 42. Since 2011, conscripts have typically been retained as reservists beyond their initial service. The call-up for reserve service has also expanded to address increased manpower needs and issues of draft evasion and defection.

([2]) “What’s New in the Administrative Order of the Syrian Regime Regarding Military Service” Enab Baladi, Published on: 11/06/2024, Link: https://bit.ly/4d8kr79.

([3]) “Special Interview on Legislative Decree No. 37 of 2023” Syrian News “Al-Ikhbariya| Channel, Published on: 01/12/2023, Link: https://bit.ly/3Sytc2k.

([4]) “General Ali Mahmoud Abbas” Ministry of Defense, Published on: 30/04/2022, Link: https://bit.ly/3WsN4oF.

([5]) “Syrian Defense Militarizes Society with Tempting Enlistment Contracts”, Enab Baladi, Published on: 28/11/2023, Link: https://bit.ly/4ccvnQb

([6]) “Our Goal is to Develop an Advanced Army Based on Enlistees”, Ministry of Information, Published on: 27/06/2024, Link: https://bit.ly/3SzIq6W

([7]) Leaked document of the plan showing the numbers of military personnel in reserve service to be discharged at the end of each phase.

([8]) “The Syrian Regime’s Army is Drained: Figures Confirm the Loss of Human Resources”, Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, Published on: 31/07/2024, Link: https://bit.ly/46Fpzxq

([9]) “Legislative Decree No. 30 of 2007, Containing the Conscription Law” ,The Parliament, Published on: 03/05/2007, Link: https://bit.ly/3EyjJSk

([10]) “Legislative Decree No. 31 of 2020” Syrian e-Government Portal, Published on: 08/11/2020, Link: https://bit.ly/3YBmP1M

([11]) “Law No. 29 of 2022”, Official Gazette, Part One, Issue No. 2, 2023, Page No.: 16, Syria Report, Link: https://bit.ly/3AhLb6E

([12]) Previous reference or see the appendix, updated Article 26, Paragraph /C/.

([13]) “Decree No. 334 of 2022”, Official Gazette, Part One, Issue No. 2, 2023, Page No.: 17, Syria Report, Link: https://bit.ly/3AhLb6E.

([14]) “Legislative Decree No. 37 of 2023”, SANA, Published on: 01/12/2023, Link: https://bit.ly/4dwhyxO.

([15]) “Legislative Decree No. 20 of 2024”, SANA, Published on: 01/08/2024, Link: https://bit.ly/3Yr6Wek.

([16]) “Legislative Decree No. 19 of 2024”, SANA, Published on: 21/07/2024, Link: https://bit.ly/3LULHdi.

([17]) “Special Interview on the Administrative Order Ending Summons and Retention”, Syrian News “Al-Ikhbariya” Channel, Published on: 17/08/2023, Link: https://bit.ly/46yHWUp.

([18]) The regime has set a minimum percentage for human resources in the army that must not fall below a certain level.

([19]) “Legislative Decree No. 30 of 2007, The Conscription Law”, ibid.

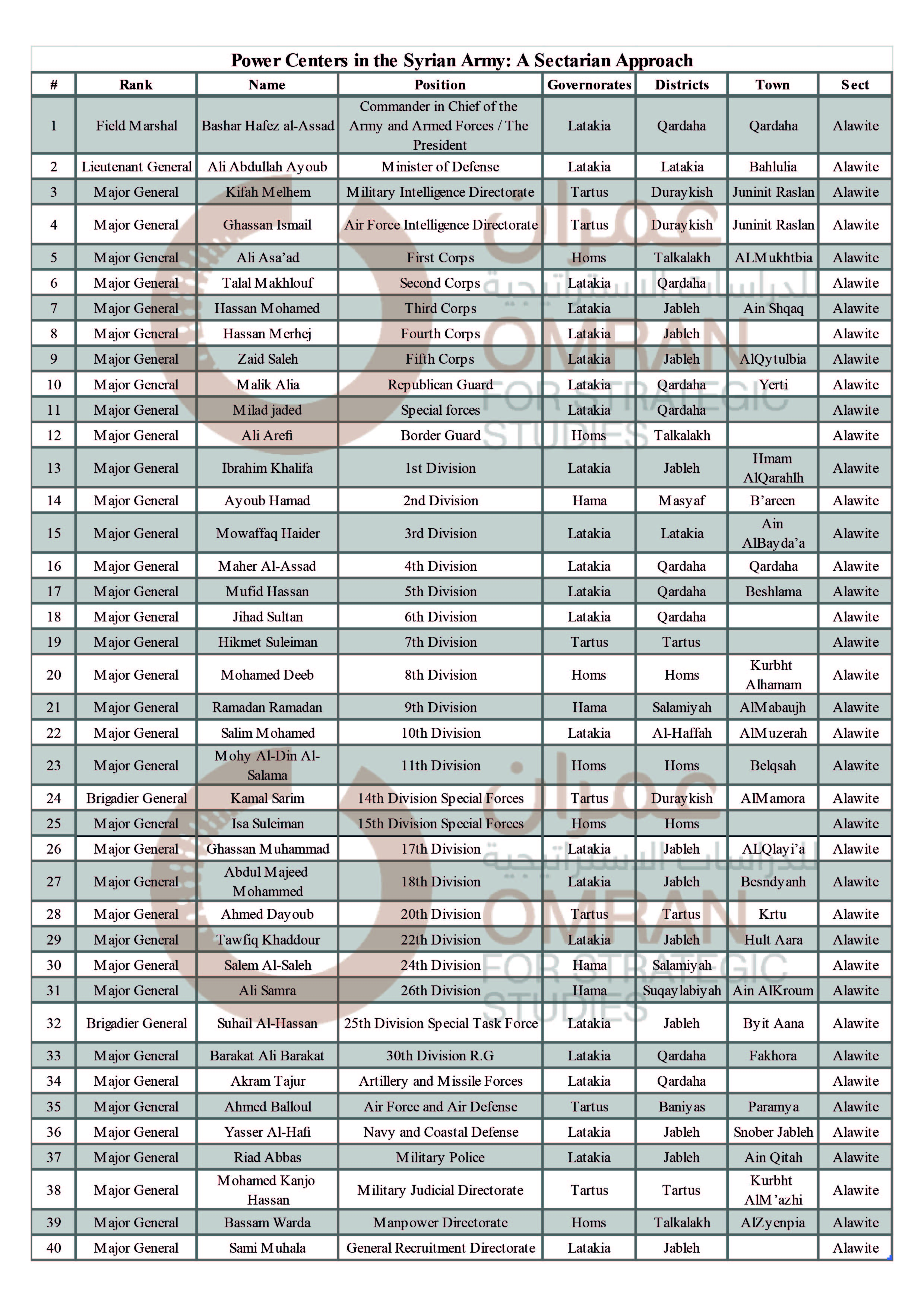

Power Centers in the Syrian Army: A Sectarian Approach

Executive Summary to Original Arabic Paper:

- Within the "Trinity of Leadership" approach which employed a sectarian balancing act, Hafez Al-Assad engineered the Syrian army’s centers of power in a manner that ensured loyalty to his regimes while preventing it from becoming a political tool against his authority. Post 2011 revolution, however, the sectarian engineering of the Syrian army tilted in favor of more Alawite officers assuming most leadership positions within the various layers of the army’s command.

- This paper examines the sectarian and territorial distribution of the most powerful 40 positions in the Syrian army as of March 2020. The paper concludes that those who occupy these sensitive positions are officers from the Alawite sect, including the Commander in Chief and the Minister of Defense, the commanders of the Military Corps, and the leaders of the intelligence branches of the Ministry of Defense.

- Latakia officers control 58% of leadership positions, Tartous officers control 17%, Homs officers 15%, while Hama officers control 10% out of these leading positions.

- There are undisclosed quotas between officers from Qardaha, Jableh, and Duraykish, where officers from Jableh command three corps and several powerful divisions. While Qardaha officers take command of a corps and an officer from Homs leads another corps.

- Qardaha officers take on the most powerful and varied of the military divisions. Whereas, two officers from the same village near Duraykish town, in the Tartous countryside, command the most powerful intelligence branches in Syria.

- The central powerful positions of the army are mainly occupied by officers from Latakia governorate, more specifically, from Jableh and Qardaha.

The following table shows the sectarian and territorial distribution of the most powerful forty positions in the Syrian army nowadays. The table also contains the names and regions of those high ranking officers including the Commander in Chief, the Minister of Defense, the Corps commanders and leaders of the formations and military division, in addition to some security and sensitive leading positions within the Syrian army:

For More in Arabic: http://bit.ly/39QaU42

Iranian influence within the Regime Army.. 2017/18 strikes that targeted Iran in Syria

Introduction

Iran was present in Syria from the very beginning of the revolution and was a strong supporter of the Syrian regime, In addition to providing the regime with weapons, soldiers, advisors, money, and political support, Iran also brought in sectarian fighters from countries including Afghanistan, Iraq, and Lebanese to form militias and fight alongside the regime.

Today in 2019, Iran's role in Syria appears to be expanding even further. Iran’s strategy has entered a new phase in which it recruits Syrians loyal to the regime to fight under direct administration and command of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), relying on local defense forces and newly formed military brigades.

Iran’s Most Significant Influences in the Syrian Army

Local Defense Forces (LDF) and National Defense Forces (NDF): A Comparison

The National Defense Forces (NDF) was established in 2012 under the direct supervision of Iran to serve as an auxiliary militia force for the Syrian army. By the end of 2017, a similar group known as the Local Defense Forces (LDF) was established in Aleppo governorate, specifically in its eastern countryside. The LDF consisted of several small local militias operated directly under the supervision of Iran, but without any legal status in Syria. Iran established and supported the LDF and linked its structure to the structure of the Syrian army, avoiding the error that occurred when the NDF were established. Recently, LDF members have been able to resolve their legal status and join the Syrian army, but their time in the LDF is not counted as time in the army's service.

On 6 April 2017, a memorandum from the "Organization and Administration Division / Branch of Organization and Armament" was issued to the General Commander of the Army and the Armed Forces, Bashar al-Assad, in order to suggest ways to formalize the status of Syrians, both civilians and military, who have worked with the Iranian side throughout the crisis. President Bashar al-Assad signed that document, in agreement, in April 2017.([1])

The document was signed by the head of the "Organization Division" Maj. Gen. Adnan Mehrez Abdo, the Chairman of the General Staff of the Army and the Armed Forces, General Ali

Ayoub, the Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and the Minister of Defense, General Fahd Jassim al-Fereij.

According to the document, the committee examined the organization of these forces from the aspects of "organization, leadership, combat, and material guarantee, rights of the martyrs, wounded and disappeared, sorting out the affairs of those commissioned who have avoided obligatory and reserve service and deserters, and the civilians working with the Iranian side." It recommended the following proposals:

- First: To organize the military and civilian elements who are fighting with the Iranian side as part of the local defense brigades in the governorates. The document includes a table showing the numbers of personnel who dodged compulsory and reserve service, deserters, civilians, and their status by governorate. The total number of troops is 88,733.

- Second: To resolve the situations of military deserters and those wanted for the compulsory and reserve service, and to transfer and appoint them to the local defense brigades in the governorates. This should include those whose situations have already been settled and are already working with the Iranian side as part of the local defense regiments. The document lists the numbers of those individuals as 51,729.

- Third: To organize volunteer contracts for civilians working with the Iranian side in the armed forces for a period of two years, regardless of the conditions of volunteerism in force in the armed forces. The document lists the number of civilians working with the Iranian side as 37,400.

- Fourth: To resolve the situation of the 1,650 officers in the 69 Officers Course who are currently working with the Iranian side in the governorate of Aleppo.

- Fifth: The leadership of local defense regiments working with the Iranian side in the governorates should remain with the Iranians in coordination with the General Command of the Army and Armed Forces until the end of the crisis in Syria, or until a new resolution is issued.

- Sixth: To provide all types of military and civilian insurance for Syrians working with the Iranian side, after they are organized into the local defense regiments in the governorates, in coordination with the competent authorities.

- Seventh: The responsibility for guaranteeing the material rights of the martyrs, wounded, and missing persons who have been working with the Iranians since the beginning of the conflict should fall on the Iranian side.

- Eighth: To issue instructions to regulate the executive instructions for military and civilian personnel working with the Iranian side, after organizing them into the local defense regiments in the governorates.

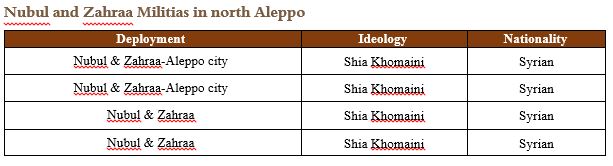

The following tables lay out the most prominent combat groups that were part of the LDF at the time of its establishment. The groups named below, in addition to several additional formations that participated in the battle of the southern Aleppo countryside in early 2018, include an estimated 45,000 fighters in total:

The LDF also spearheaded the battles against ISIS in Deir Ezzor and the southern Raqqa countryside. These are now the military,security, and administrative forces controlling the area stretching from the southern countryside of Deir Ezzor, passing through southern Raqqah, all the way to the eastern countryside of Aleppo and the Aleppo city. The following are the most important formations that joined the LDF in early 2018:

| Nationality | Deployment | Name |

| Syrian | Aleppo | Doshka Brigade |

| Syrian | Aleppo | Al-Safira Brigade |

| Syrian | Hama | Al-Berri Brigade |

| Syrian | Hama | Al-Hikma Brigade |

| Syrian | Aleppo | Al-Nayrab Regiment |

| Syrian-Iraqi-Lebanese | Aleppo - Raqqah | Islamic Resistance in Syria |

| Syrian | Homs | Al-Rida Forces |

| Syrian | Homs | Al-Radwan Forces |

| Syrian | Idlib | Suqur al-Dhaher Forces |

| Syrian | Aleppo | Khan al-Asal Eagles |

| Syrian-Iraqi | Deir Ezzor | Force 313 |

| Syrian | Hama | Al-Ghadab Christian Forces |

| Syrian | Tadmur(Palmyra) | Imam Zayb al-Abdeen Brigade |

| Syrian | Lattakia Countryside | Al-Qirsh Group |

Brigade 313: The IRGC’s New Military Formation

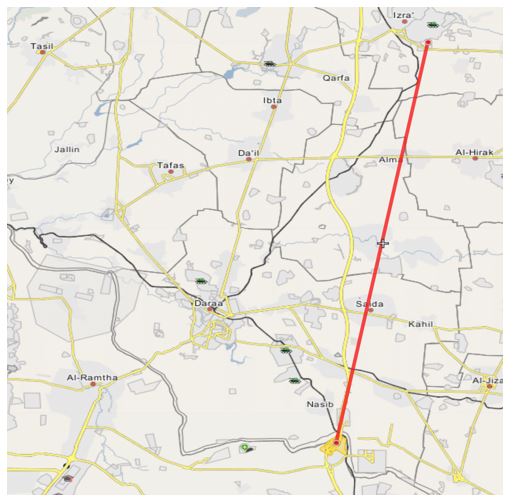

Iran has continued its efforts to expand into southern Syria despite international agreements aimed at limiting its role in the region. In doing so, Iran is violating the Hamburg agreement between Russia and the United States, which required Iranian troops and affiliated militias to stay at least 35 kilometers away from the Syrian-Jordanian border. ([2])

In November 2017, the IRGC established a special military body on the southern fronts of the Syrian army, called "Brigade 313." That same year, the brigade opened a recruitment center in the city of Izra'a in Daraa governorate. Through this center, Brigade 313 attracted more than 200 young Syrians from Daraa, most of whom were young people who reconciled their status with the regime in 2017. New members of Brigade 313 receive an identity card bearing the emblem of the IRGC, which ensures their ability to pass through the regime force checkpoints. Within two weeks of joining Brigade 313, recruits are enrolled in training camps in Izra'a and Sheikh Meskin.

Brigade 313’s headquarters is located about 30 kilometers from the border with Jordan and about 45 kilometers from Israel. For this reason, the brigade's location poses a direct threat to the agreement between Washington and Moscow.

Iran's efforts to recruit local elements and integrate other militias with these bodies ramped up in anticipation of international efforts to deport Iranian-backed militias containing foreign elements, mostly from Afghanistan, Lebanon, and Iraq.

Major Israel and U.S. attacks on Iranian forces and affiliated militias in Syria

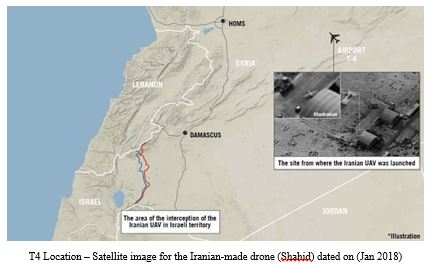

10 February 2018 – Israeli attacks

- An Israeli Apache helicopter intercepted unmanned Iranian reconnaissance aircraft that entered the Golan Heights and sirens were heard in the area of Besan, Israel.

- Following the drone infiltration, Israeli warplanes attacked Iranian targets at T4 (Tiyas) airbase in Syria.

- One of the Israeli warplanes crashed near the Galilee in northern Israel after it was hit by a missile launched from Regiment 16 in Syria, which is controlled by Iran.

Following the crash of the Israeli warplane, the Israeli Air Force responded by targeting several, locations near the administrative border between Damascus governorate and the southern governorates of Daraa and Quneitra. Specifically, Israel targeted areas where the Iranian-backed Brigade 313 forces andLebanese Hezbollah forces are stationed in the town of Al-Dimas on the Damascus-Beirut road near the Syrian-Lebanese border.

The Israeli Defense Force (IDF) media announced that seven locations were successfully destroyed (three Syrian air defense batteries and four targets belonging to Iran), and confirmed that Syrian regime anti-aircraft missiles capacity dropped to 50% after most of its locations were destroyed.

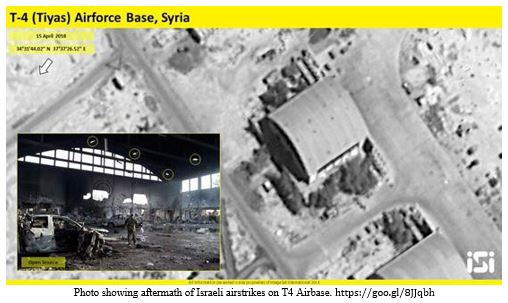

9 April 2018 – Israeli attacks

Israeli warplanes fired a number of missiles at the T4 (Tiyas) airbase from Lebanon’s airspace. Seven IRGC forces were announced dead following the attack.

Iranian locations that were targeted before, after, and during the April 2018 strikes by the U.S. and its allies

| 2018 Major hits before the US strike on Syria | |||||||

| Date | Province | Area | Location | Local Forces | International Forces | Attacker | Note |

| 10/2/2018 | Homs | Eastern Rural | Tayyas Airbase (T4) | Regime and Pro- Iran forces | IRGC and Hezbollah | Israel | Strike Destroyed: Iranian Drone - main control tower - military accommodation |

| 9/4/2018 | Homs | Eastern Rural | Tayyas Airbase (T4) | Regime and Pro- Iran forces | IRGC and Hezbollah | Israel | Strike Destroyed: Three warehouses - the death of 7 IRGC fighters |

| 2018 Major hits During the US strike on Syria | |||||||

| Date | Province | Area | Location | Local Forces | International Forces | Attacker | Note |

| 14/4/2018 | Damascus | The City | 41 Special forces HQ | No Forces | Hezbollah | Unknown | The strike is not mentioned in foreign or local media |

| 14/4/2018 | Homs | Qatyna Lake | Military Warehouse | No Forces | Hezbollah | Unknown | Hezbollah didn’t publish anything about this location |

Between 15 and 18 April 2018, after the U.S.-led attacks on Syria, two Iranian locations in Syria were reportedly targeted by unknown attacker: one in the Azzan Mountains in southern Aleppo and the other near al-Shiraat Airbase. There was no confirmation from the regime’s media regarding these attacks, only local sources confirmed seeing or hearing the explosions.

| Full list of All the Location targeted during the US hit (Confirmed or Not) | ||||

| Province | Location | Presence of IRGC | Presence of Pro-Iran | Strike Confirmation |

| Hama | Scientific Research in Misyaf | Yes | Yes | Not Confirmed |

| Homs | Hezbollah HQ North of al-Qusayr | No | Yes | Not Confirmed |

| Homs | Military Warehouse Near Qatyna lake | No | Yes | Confirmed |

| Damascus | Scientific Research in Barzeh | No | Yes | Confirmed |

| Damascus | Scientific Research in Jamraya | No | Yes | Confirmed |

| Damascus | Al-Dumyer Airbase | No | Yes | Not Confirmed |

| Damascus | Al-Kiswa Military Locations | Yes | Yes | Not Confirmed |

| Damascus | Brigade 105 | No | No | Confirmed |

| Damascus | Mazzeh Airbase | No | No | Confirmed |

| Damascus | 41 Special Forces HQ | No | Yes | Confirmed |

| Damascus | Rhayba Military Locations | No | Yes | Not Confirmed |

8 May 2018 -Israeli attacks

Israeli missiles struck the first Armored Division (Jabal Al-Mani) in al-Kiswa near the Syrian capital Damascus. The attack took place after an hour after U.S. President Donald Trump announced he was withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal. At least 13 fighters were killed in the attack; seven of them were members of the IRGC and other Iran-backed militias.

Hitham Abdul Rasol, IRGC commander and developer of "Fajr-3" Iranian missile defense system, visited two Iranian locations on the same day of the attack: one in al-Zabadani and the other at the Damascus International Airport. Both of these locations are likely to host "Fajr-3" systems.

10May 2018 – Israeli attacks

After Iranian forces fired 20 rockets at Israeli military positions in the Golan Heights at night on 9 May 2018, Israeli Air Force planes entered Syrian airspace to attack dozens of Iranian targets inside of Syria. The following table lists the major locations that were targeted:

| Province | Location | Coordinates | IRGC | Pro Iran Militias |

| Damascus | Western Ghouta (Tell Harboon) | 33°21'7"N 35°52'15"E | No | Yes |

| Quneitra | Khan Arnaba | 33°10'56"N 35°52'51"E | No | Yes |

| Quneitra | Khan Arnaba (Tell al-Qubu) | 33°12'12"N 35°53'3"E | No | Yes |

| Damascus | Kanakir (Brigade 121) | 33°16'46"N 36°4'51"E | Yes | No |

| Damascus | Al-Kiswa | 33°22'58"N 36°14'5"E | Yes | Yes |

| Damascus | Al-Kiswa (1st Armoured Division) | 33°21'6"N 36°17'39"E | Yes | Yes |

| Quneitra | Khan Arnaba (Tell al-Shaar) | 33°10'29"N 35°56'34"E | No | Yes |

| Daraa | Mahji (Air Defense Base) | 32°56'8"N 36°12'34"E | No | Yes |

| Daraa | Izraa (12th Armoured Brigade) | 32°51'29"N 36°16'23"E | No | Yes |

25December 2018 – Israeli attacks

On 25 December 2018, Israel launched a series of airstrikes against military targets in Damascus and its countryside, targeting military sites and weapons stores where pro-Iranian forces were deployed. These strikes were launched in two stages and are unique in terms of timing, targets, intensity, and messaging.

These Israeli attacks were the ninth of their kind in 2018. They were the second such strikes to take place after Russia's deployment of the S-300 air defense missile system and the first since Donald Trump announced the withdrawal of U.S. forces from eastern Syria. Israel’s 25 December strikes were notable because they indicated the return of coordination between Moscow and Tel Aviv in Syrian airspace in support of their common interests in the reduction of Iranian influence and potential expansion in Syria. They were also notable because they conveyed the clear message that Israel would continue its policy of striking Iranian forces and infrastructure in Syria despite the U.S. withdrawal. The intensity and length of the attacks may also indicate Israel's readiness for a future escalation against Iran in Syria and serve to push Russia and the U.S. to deal more seriously with the dilemma of expanding Iranian influence.

Israel sees the American withdrawal from Syria as an opportunity to intensify its pressure on Iran and test Iran’s reaction. If Iran responds aggressively to Israel’s intensification, it will lead to regional escalation and pressure the U.S. to adopt more punitive policies and measures against Iran, possibly delaying the U.S. withdrawal from Syria. It may also delay Iran's plans to expand in the eastern region of Syria to counter the growing Russian presence there. However, Iran may also choose to absorb these Israeli strikes and respond either on a small scale or not at all, in order to focus on filling the vacuum in the eastern region following the U.S. withdrawal. It will encourage Israel to launch more attacks against inside Syria during the transitional U.S. withdrawal period if it is actually completed, which is a likely scenario.

17 January 2019 – Israeli attacks

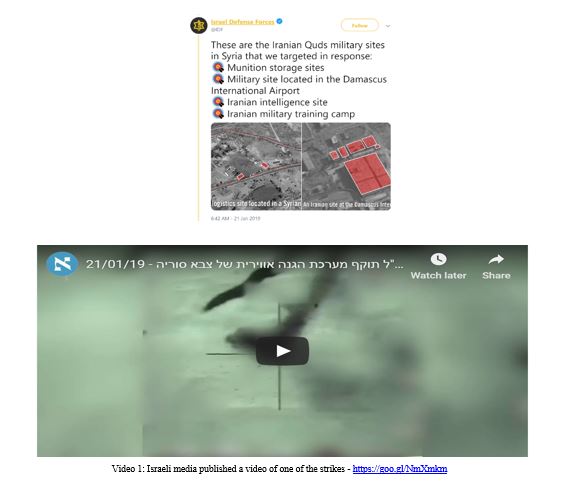

The Israeli Air Force struck some ten targets in Syria overnight from Sunday 20 January – Monday 21 January. The attack targets included arms warehouses at Damascus International Airport and other locations, and sites belonging to IRGC including an Iranian intelligence site and an Iranian training camp. The attacks were in response to a ground-to-ground missile that was fired at Israel from Syria a day earlier and intercepted.

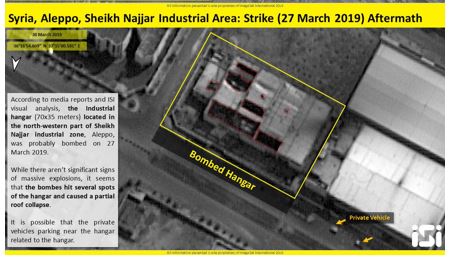

27 March 2019 – Israeli attacks

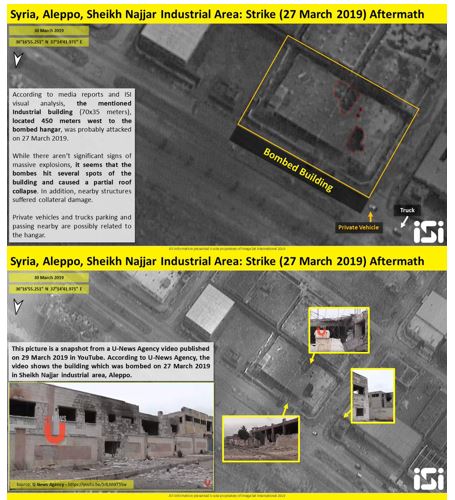

The Israeli air force launched airstrikes on the industrial zone in the northern city of Aleppo, causing damage only to materials as per the official pro-Regime news agency "SANA," while opposition sources said the strikes hit Iranian ammunitions stores and a military airport used by Iranian-backed militia's forces. ([3])

Inside sources confirmed that the Israeli airstrikes targeted two warehouses in the industrial area of Sheikh Najar. The warehouses contained light and medium ammunition, based on the type of ammunition that was heard in the blast after the airstrikes.

These warehouses are under the control of Iranian-backed militias, until now the identity of the militia, which was hit, is under investigation. However, according to previous information Badr Organization, Fatemiyoun, Hezbollah, and al-Nujbaa are based in this area.

The site of the airstrikes was locked down for seven hours then it was opened only for LDF forces and SANA, which published pictures of the site showing that the raid targeted an empty warehouse and only caused martial damage.

ISI published recent pictures of the location that was targeted, the pictures showed several damaged warehouse in the area of the airstrikes, and it's also visible that these airstrikes targeted specific locations and not a random hit in order to destroy empty buildings as per the official regime news agency statement.

Pro-Iranian accounts promote that the strike was in line with Turkey's desire to empty the towns of Nubl and Zahraa to form a Sunni belt, that's why the regime with the support of the Iranian took the decision to intensify the military presence to prevent any future Turkish military plan.

13 April 2019 – Israeli attacks

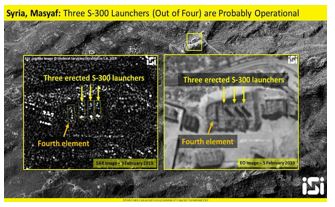

The Israeli Air Force launched airstrikes from Lebanese airspace on targets in the Syrian province of Hama. According to inside sources and Pro-Regime media, the target was a military location of IRGC and other Iranian-backed militias and the area is located between the research center and al-Talaa Camp.

In February 2019, ISI center published pictures showing the Russian S-300 surface-to-surface missile system based in Syria near the targeted area. This was the third strike in 2019 that explicitly targeted Iranian-backed militias.

The first one targeted Damascus International Airport, the second was on Aleppo airport and the industrial zone, while the latest, as we mentioned, it targeted Iranian-backed militias’ bases near the city of Masyaf in Hama province.

Conclusion

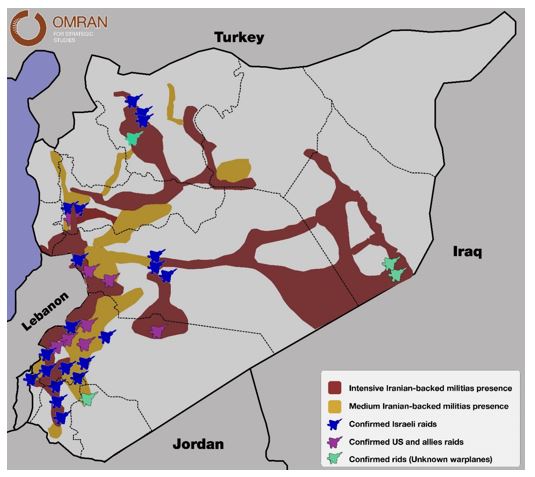

Since 2017, Iranian military sites in Syria have been continuously targeted by Israel, the U.S. and their allies. These attacks pushed Iran to find a way to protect its presence. Since 2018 Iran has been reintegrating its militias into military formations affiliated with the Syrian regime, which has led to reducing the intensity of the raids against them but did not prevent them.

In general, the raids on Iranian sites did not have a long-term impact on Iran's strategy and goals in the region. The areas under Iranian influence in Syria remain large with various levels of infiltration (military, security, social and economic). This Iranian infiltration and expansion strategy came as a precautionary measure if air strikes were to continue.

([1])Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi. Administrative Decisions on Local Defence Forces Personnel: Translation & Analysis. 3-5-2017. Link: https://goo.gl/ngXYKc

([2]) 2 The Russian-American "Hamburg Agreement" on Syria: Its Objectives and Implications, Arabs 48, 11-7-2017, https://goo.gl/hW4GAr

([3]) Location of the raid: http://wikimapia.org/m/#lat=36.2631&lon=37.255325&z=11&l=36&m=b

Transformations of the Syrian Military: The Challenge of Change and Restructuring

Executive Summary

- Throughout its history, the Syrian military has gone through a number of stages in its structural and functional evolution. These include processes undertaken based on the need to develop the military’s professional and technical capacity, or as required for the domination and control of the regime over the army, or as dictated by the war conditions. But since Hafez al-Assad took power, the military has become a major actor in local “conflicts,” whether as a result of the social composition of the military and the sectarian engineering efforts started by Hafez al-Assad and continued by Bashar al-Assad, the special privileges granted to military members, or as a result of the military doctrine that is customized for the preservation of the regime and not based on national ideals. Some of the most significant structural and human changes in the history of the Syrian military took place between 2011 and 2018. These shifts included the entry of auxiliary non-Syrian forces, both individuals and groups, which completely changed the role of the “army” from that of a traditional national army into a force used primarily to protect the ruling regime.

- As a result of the unexpected outbreak of military operations across the country against a popular uprising, there was a significant increase in the number of amendments made to laws governing the military establishment in order to address gaps in those laws. Some of the laws were ignored in favor of custom and tradition. This was reflected in the promotion and evaluation of officers based on sectarian or regional affiliations. The introduction of a partial mobilization in Syria without official certification of the decision as a result of the events starting in 2011, and the issuance of a new mobilization law at the end of 2011, supported the regime's efforts to distribute mobilization tasks to all state institutions and departments. Previously, the last law on mobilization had been issued in 2004.

- At the outset of the uprising in Syria, the military's deployments were characterized by complete chaos. The regime's use of local and foreign militias, in addition to the Iranian and Russian regimes, transformed this deployment from complete chaos to a more organized chaos. The regime was able to recapture many villages and cities based on a strategy of collective punishment, scorched earth offensives, and guerrilla warfare. The Syrian regime's use of local and foreign militias led to an imbalance in the structure and responsibilities of the army during the revolution, so that the military became a more Alawite-dominated institution because of its reliance on its Alawite members. Most of the officers were corrupt, and that corruption became much worse during the years of revolution, causing the military to become increasingly distant and isolated from society. This pushed the officers to collude with corrupt networks within the regime and to exploit them to achieve further gains and accumulate wealth.

- In 2018, the military landscape witnessed many major transformations, most notably the division of the country into three main international spheres of influence, each of which contained a diverse mix of local political powers. In the first sphere controlled by the regime, there were indicators of increased Iranian and Russian influence, as well as an attempt to consolidate the militia scene, with some being dissolved and others linked to Iran being integrated and merged with others. In the second sphere: includes the armed opposition forces in northern Syria backed by Ankara, the map of relevant armed actors became more disciplined and contained under the framework of the Astana talks. Opposition forces displaced from southern and central Syria were restructured by Ankara in support of the Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch operations. In the third sphere: the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) continued to perform their security and military functions under the self-administration project and its legal framework. At the same time, their negotiations with the Assad regime continued, leaving their options wide open and making it more likely that the situation would get more complicated because of the lack of a clear policy from the Americans who supported the SDF on the one hand and pushed for further negotiations on the other.

- The regime’s attempts to reduce and contain the roles carried out by Iranian and local militias were not comprehensive or well organized. On one hand, many Iran-backed militias became integrated into the official regime military structure following the formalization of Iranian operations in Syria, which did not reduce or contain its power or impact. On the other hand, the overall reintegration strategy was not adhered to especially with regards to local militias or groups that settled through reconciliation agreements, as the objective of conducting operations against opposition forces is still prevalent and dominating deployments. This process of reintegration will face further obstacles that will greatly hinder any restructuring process as a result of the deep infiltration of such militias and the diverse roles they play in society and within the security sector.

- The data and indicators examined by the papers contained in this book highlight the deep and significant impact of transformations in the military institution both in the medium and long terms. These transformations are observed in the structural and functional imbalances of the military institution especially as it faces a deficit of power, capacity, and resources. Furthermore, the regime’s military institution has become one of many other actors in the scene and often held hostage to local and international networks of power, whether it is the Russian or Iranian or other local groups. It is also restricted in its capacity because its imbalanced societal composition, has not adopted political neutrality, and the ideological party doctrine that dominates. All this necessitates a rebuilding strategy that is absent from the current regime’s agenda as well as its allies in favor for superficial rehabilitation for the purpose of regaining control of territory and society.

- In the face of the current frame of reference that guide the reform course of the military institution, the absence of a national agenda or vision should be noted. This vision should stipulate the requirements for the reform process, most important of which is the political process and change, depoliticizing the military institution, protecting political life from military interferences, and the reinforcement of healthy and normal civil-military relations that enhance its performance.

Introduction

Based upon the need to redefine the roles of the Syrian military institution in light of the profound transformations in the concept of nation-state, Omran Center for Strategic Studies launched this research project to further analyze those transformation and address the challenge of change and restructuring. The approach first deconstructs and assesses the functions and structures of the Syrian army, its doctrine, and causes behind its involvement and interference in social and political affairs in accordance with the regime’s philosophical vision of domination and totalitarian control. The papers contributed by researchers in the first phase of this project are as follows:

- The Syrian Army 2011-2018: Roles and Functions

- Military Actors and Structures in Syria in 2018

- Stability and Change: The Future of the Military in Syria

- Annex Report 1: Significant Transformations in the Army: 1945-2011

- Annex Report 2: Laws and Regulations Governing the Military After 2011.

The outputs of papers and reports in this book assess indicators of instability in the map of military actors and measure its impact on the centrality of defense and security functions and the future end game for the nodes of power within the military after possible reintegration processes. It also focuses on the relationship between the military and political spheres, in the sense that it evaluates the potential for military actors to contribute to various avenues of reform, including the redistribution of power in a legally decentralized manner. Similarly, it also looks at the changing political situation and the positions taken by regional and international backers of armed groups, which influence the decisions of military actors, leaving them with limited options.

This book first outlines the main historical developments in the Syrian military in order to establish a more comprehensive understanding of the shortfalls in the military structures and how they developed. It also looks at the most important laws and amendments related to the military establishment and how they have evolved over time. The book also describes how the military leadership used these laws after the start of the Syrian revolution to recruit fighters to the military that were completely loyal to the ruling regime.

The papers and reports in this book try to answer a number of key questions such as: does the military in its current state embody features of effectiveness, adopt a national outlook, have the capacity and ability required to preserve and promote the outputs of a political process, and able to create and promote conditions for stability? Addressing these questions necessitated first to recognize the positioning of reform policies within the current and future military institution agenda, and to assess the presence or lack of a cohesive and stable structure after the profound transformations it witnessed. Finally, the book outlines an initial vision for a framework for reform that would allow this institution to be a catalyst for societal cohesion and adopt a politically neutral position to become a source of stabilization is Syria.

Omran Center plans to launch a second phase with additional papers to be based on the outcomes of papers contained in this book as well as discussion and feedback received from participants in the workshop held in Istanbul on October 25th, 2018 to focus potentially on the following topics:

- Sectarianization mechanisms in the Syrian military.

- Power nodes and networks in the Syrian military.

- Management of surplus manpower: a case study of the 4th and 5th corps.

- The military judicial system.

- Non-technical challenges in the reform of the military establishment.

For More Click here