Events

Significant Economic Cooperation Between The Syrian Regime and Iran During 2018-19

Executive Summary

Iran, a major ally and enabler of the Syrian regime, is increasingly engaged in competition over access to the Syrian economy now that there are new opportunities for lucrative reconstruction contracts. This report sheds light on the economic role played by Iran in Syria through its local representatives and Iranian businessmen. It also explores the (limited) impact of the European Union and U.S. Treasury sanctions on Iran's economic instruments in Syria.

Introduction

Iran has invested heavily in the protection of the Syrian regime and the recovery of its territories. Iran’s main objectives in Syria have been to secure a land bridge between its territory and Lebanon, and to maintain a friendly regime in Damascus. Much of Iran’s investment has been military, as it has financed, trained, and equipped tens of thousands of Shi’a militants in the Syrian conflict. But Iran has also made major financial and economic interventions in Syria: it has extended two credit lines worth a total of USD 4.6 billion, provided most of the country's needs for refined oil products, and sent many tons of commodities and non-lethal equipment, notwithstanding the international sanctions imposed on the regime. In exchange for its commitment to ensuring Assad’s survival, Tehran has expected and demanded large concessions in terms of access to the Syrian economy, especially in the energy, trade, and telecommunications sectors.

Key Iranian Companies

Iran has provided crucial economic assistance to the Assad regime in order to prevent its fall and to ensure that it can meet its fuel needs. In return, Iran demanded access to significant investment opportunities in key sectors of the Syrian economy, notably: state property, transportation, telecommunications, energy, construction, agriculture, and food security.

Since 2013, the Iranians have aided Assad through two main channels. First, it extended two lines of credit for the import of fuel and other commodities, with a cumulative value of over USD 4.6 billion. In order to position itself strategically as the lynchpin of the Syrian economy, Iran restricted the benefactors and implementers of these credit lines to its own national companies. It can thus continue to provide the regime with a lifeline in terms of goods and energy supplies, but in return it can control key parts of the Syrian economy.

The following list includes major Iranian companies that have announced a return to business-as-usual in Syria. Each brief overview gives a description of the company’s involvement in Syria, followed by basic information about the company.

Khatam al-Anbia Construction Base

Has demonstrated an interest in carrying out reconstruction work on Syria infrastructure.

Khatam al-Anbia Construction Base is involved in construction projects for Iran's ballistic missile and nuclear programs. It is listed by the UN as an entity of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), with a role “in Iran's proliferation-sensitive nuclear activities and the development of nuclear weapon delivery systems” (Annex to U.N. Security Council Resolution 1929, June 9, 2010). The company is under the command of Brigadier General Ebadollah Abdollahi.

Khatam al-Anbia conducts civil engineering activities, including road and dam construction and the manufacture of pipelines to transport water, oil, and gas. It is also involved in mining operations, agriculture, and telecommunications. Its main clients include the Ministry of Energy, Ministry of Oil, Ministry of Roads and Transportation, and Ministry of Defense.

Since the company’s founding in 1990 it has designed and implemented approximately 2,500 projects at the provincial and national levels in Iran. It currently works with 5,000 implementing partners from the private sector. An IRGC official recently revealed that a total of 170,000 people currently work on Khatam al-Anbia’s projects and that in the past 2.5 years it has recruited 3,700 graduates from Iran’s leading universities.

Company officials for Khatam al-Anbia include IRGC General Rostam Qasemi and Deputy Commander Parviz Fatah. Other personnel reportedly include Abolqasem Mozafari-Shams and Ershad Niya.

MAPNA Group

- Supplying five generating sets for gas and diesel operations (credit line)

- Construction of a 450 MW power plant in Latakia (credit line)

- Implementation of two steam and gas turbines for the power plant supplying the city of Baniyas (credit line)

- Rehabilitation of the first and fifth units at the Aleppo power plant (credit line).

MAPNA is a group of Iranian companies that build and develop thermal power plants, as well as oil and gas installations. The group is also involved in railway transportation, manufacturing gas and steam turbines, electrical generators, turbine blades, boilers, gas compressors, locomotives, and other related products. The Iran Power Plant Projects Management Company (MAPNA) was founded in 1993 by the Iranian Ministry of Energy. Since 2012, the group has been led by Abbas Aliabadi, former Iranian Deputy Minister of Energy in Electricity and Energy Affairs.

In 2015, MAPNA sealed a USD 2.5 billion contract, Iran’s largest engineering deal to date, to supply Iranian technical and engineering services for the construction of a power station in Basra in southern Iraq.

Mobile Telecommunication Company of Iran (MCI)

A contract to build Syria’s third mobile network (suspended).

MCI is a subsidiary of the Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI), which is partially owned by the IRGC. MCI brings in approximately 70 percent of TCI’s profits. MCI provides mobile services for over 1,000 cities in Iran and has approximately 66 million Iranian subscribers. It provides roaming services through partner operators in more than 112 countries.

Iranian Companies Active in Syria in 2019

Table 1: List of all Iranian companies with ongoing contracts in Syria - 2019

| Name | Arabic Name | Main Activity | Agreement | Headquarters Address |

| Safir Noor Jannat | سفير نور جنات | Food industries, detergents, and electronics | An old MOU dating back to 2015 to supply Syria with flour | No. 8, Mohamadzadeh st., Fat-h- highway 4Km. Tehran |

| Behin Gostar Parsian | بهين كستر بارسيان | Food industries | No information | Unit 5. No 14. Shahid Gomnam Street. Fatemi Sq. Tehran |

|

Peimann Khotoot Gostar Company جزء من مجموعة PARSIAN GROUP |

بيهين غوستار بارسيان | Electrical power, electronics, and technology | 2017 MOU with the batteries companies in Aleppo, the General Company for Metallurgical Industries in Barada, and Sironix, to carry out electricity projects in several locations in Syria. | Tehran Province, Tehran, District 22, No: 5, Kaj Blvd, 14947 35511, Iran |

| Feridolin Industrial & Manufacturing Company | شركة فريدولين | Electrical appliances | No information | ----- |

| Tadjhizate Madaress Iran. T.M.I. Co. | ---- | Decor and furnishings | No information | No. 198, Dr. Beheshti St., After Sohrevardi Cross Rd., 157783611, Tehran, Iran, Tehran |

| Trans Boost | ترانس بوست | Electricity | Electrical transformer station (230 66 20 kV) in the Salameh, Hama area | ---- |

| B.T.S Company | بي تي سي | Import and export, and commercial brokerage | No information | ------ |

| Nestlé Iran P.J.S. Co. | شركة نستله | Food industries | Supply of milk to Syria for the time being | 6th Floor, No.3, Aftab Intersection, Khoddami St., Vanak Sq., Tehran, Iran |

Recruiting Local Partners (Iran vs. Russia)

Iran and Russia have been competing over the reconstruction of Syria and the potentially lucrative investment opportunities that come with it because both countries hope to recoup some of their outputs from years of supporting the Assad regime and also because both hope to maintain their influence in the post-war era. Both Tehran and Moscow are therefore striving to win over major players in the Syrian political and economic spheres whom they hope to rely on to facilitate their business deals and ensure their respective interests. Consequently, both countries have established economic councils to oversee their ventures and to organize relations with their respective Syrian partners.

The following descriptions of the Syrian-Russian and Syrian-Iranian business councils cover their structures, the total number of members, the most prominent players, and the companies affiliated with their members.

The Syrian-Russian Business Council

The Syrian-Russian Business Council (SRBC) includes 101 Syrian businessmen and a number of Russian counterparts. It is divided into seven committees covering the main sectors of the economy:

- Engineering

- Oil and gas

- Trade

- Communications

- Tourism

- Industry

- Transportation

The Syrian membership of the SRBC includes many influential names, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Members of the Syrian-Russian Business Council

| Notable Names | Total Number of Businessmen |

| Samir Hasan (Chairman, SRBC) | 101 |

| Jamal al-Din Qanabrian (Deputy Chairman, SRBC) | |

| Mohammed Abu al-Huda al-Lahham, (Secretary, SRBC) | |

| Fares al-Shehabi (Businessman) | |

| Mehran Khunda (Businessman) | |

| Bashar Nahad Makhlouf (Businessman) |

Of these figures, three are particularly prominent:

- Jamal al-Din Qanabrian has served as a member of the Consultative Council of Syria’s Council of Ministers since 2017 (the Council presents proposals and consultations to the government on economic and legislative affairs). He is also a member of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

- Samir Hassan, the chairman of the Syrian-Russian Business Council, is a partner in Sham Holding Company, which is owned by Rami Makhlouf.

- Mohammed Abu al-Huda al-Lahham, also a member of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce, is believed to have strong ties with Dhul-Himma Shalish, the powerful Syrian construction mogul and cousin and personal guard of Hafiz al-Assad.

The SRBC also employs a number of Syrian businessmen of Russian nationality, most notably George Hassouani, who was formerly involved in oil and gas deals with ISIS.

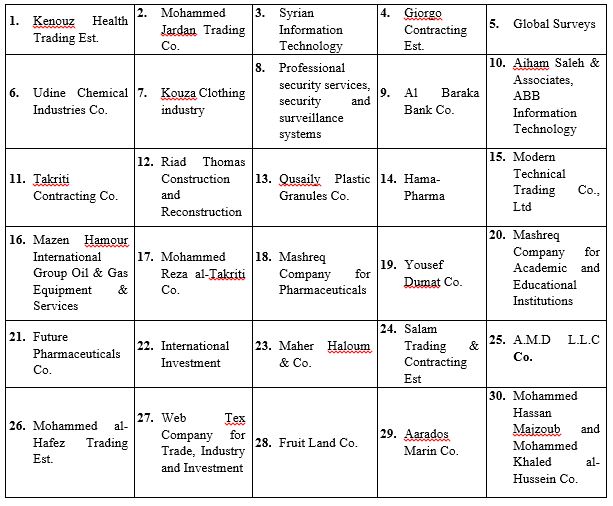

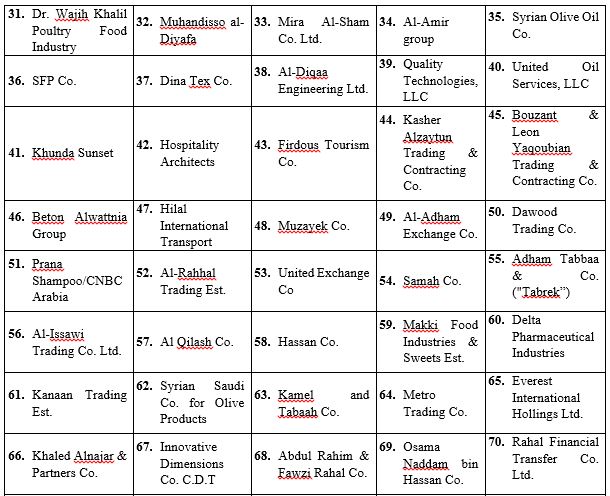

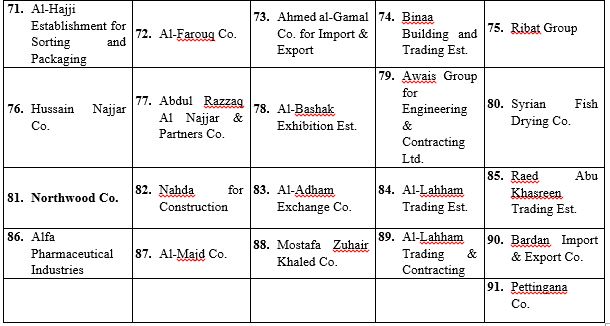

The number of Syrian companies included in the Syrian-Russian Business Council is estimated at 91. These companies are involved in import and export, general trade, textiles, clothing, petrochemicals, energy, and, in a small number of cases, private security operations (see Table 3).

Table 3: Companies in the SRBC

The Syrian-Iranian Business Council

By comparison, Iran has had less success with its business council venture than Russia. The Syrian-Iranian Business Council (SIBC) was established in March 2008, and was initially led by Hassan Jawad. It was reconstituted in 2014 with nine members, as shown below in Table 4.

Table 4: Members of the SIBC

| Notable Names | Total Number of Businessmen |

| Samer al-Asaad (President, SIBC) | b |

| Iyad Mohammed (Treasurer, SIBC) | |

| Mazen Hamour (Businessman) | |

| Osama Mustafa (Businessman) | |

| Hassan Zaidou (Businessman) | |

| Khaled al-Mahameed (Businessman) | |

| Abdul Rahim Rahal (Businessman) | |

| Mazen al-Tarazi (Businessman) | |

| Bashar Kiwan(Businessman) |

Some of these figures have significant economic influence:

- Mazen al-Tarazi is a prominent businessman with investments in the tourism sector as well as in real estate (including the project to redevelop Marota City in western Damascus). He has founded a number of companies in Syria, Kuwait, Jordan and elsewhere that offer services in oil well maintenance, advertising, publishing, paper trading, and general contracting. He also owns a number of newspapers, including Al-Hadaf Weekly Classified in Kuwait, Al-Ghad in Jordan, and Al-Waseet in Jordan.

- Iyad Mohammed is the Head of the Agricultural Section of the Syrian Exporters' Union.

- Osama Mustafa is a member of the People's Assembly, where he represents Rural Damascus Governorate. He served as Chairman of the regime’s Rural Damascus Chamber of Commerce between 2015-2018.

The number of companies owned by Syrian businessmen who are members of the SIBC board is estimated at 10 (see Table 5).

Table 5: Companies Owned by SIBC Members

|

Abdul Rahim & Fawzi Rahal Co. |

Al-Sharq Bank |

| Al-Shameal Oil Services Co. |

National Aviation, LLC |

| Rahal Money Transfer Co. |

Ebdaa Development & Investment Co. |

|

Mazen Hamour International Group |

Development Co. for Oil Services |

|

Dagher & Kiwan General Trading Co. |

Concord al-Sham International Investment Co. |

Because of the relatively small number of Syrian members of the SIBC, Iran is making additional efforts to woe Syrian businessmen. According to private sources, Syrian businessmen are seeking contracts with Iranian companies in return for being granted a share of the value of the contract. Table 6 shows key Syrian figures engaged with Iran.

Table 6: Syrian Businessmen Engaged with Iran

| Name | Position | Name | Position |

|

1.Faisal Talal Saif |

Head of the Suweida Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

2.Mohamed Majd al-Din Dabbagh |

Head of the Aleppo Chamber of Commerce |

|

3.Jihad Ismail |

Head of the Quneitra Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

4.Abdul Nasser Sheikh al-Fotouh |

Head of the Homs Chamber of Commerce |

|

5.Tarif al-Akhras |

Head of the Deir Ezzor Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

6.Osama Mostafa |

Head of the Rural Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

|

7.Adeeb al-Ashqar |

Merchant from the Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

8.Kamal al-Assad |

Head of Latakia Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

9.Albert Shawy |

Merchant |

10.Hamza Kassab Bashi |

Head of Hama Chamber of Commerce |

|

11.Amal Rihawi |

Director of International Relations at the Commercial Bank of Syria |

12.Mohammed Khair Shekhmous |

Head of the Hasaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

13.Elias Thomas |

Merchant |

14.Wahib Kamel Mari |

Head of the Tartous Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

15. |

Merchant |

16.Qassem al-Maslama |

Head of the Daraa Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

17.Saeb Nahas |

Merchant |

18.Aws Ali |

Merchant |

|

19.Ghassan Qallaa |

Head of the Federation of Chambers of Commerce |

20.Iyad Abboud |

General Manager of MOD |

|

21.Louay Haidari |

Merchant |

22.Ayman Shamma |

Merchant |

|

23.Mohamed Hamsho |

Secretary-General of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

24.Bassel al-Hamwi |

Merchant |

|

25.Mohamed Sawah |

Head of the Syrian Exporters Union |

26.Khaled Sukar |

Merchant |

|

27.Mohamed Keshto |

Head of the Union of Agricultural Chambers |

28.Sami Sophie |

Director of the Latakia Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

29.Marwa al-Itouni |

Head of Syrian Businesswomen |

30.Salman al-Ahmad |

Union of Syrian Agricultural Chambers |

|

31.Mustafa Alwais |

Rami Makhlouf 's partner |

32.Samir Shami |

Syrian Exporters Union |

|

33.Nahed Mortadi |

Merchant |

34.Gamal Abdel Karim |

Merchant |

|

35.Nidal Hanah |

Merchant |

36.Zuhair Qazwini |

Merchant |

|

37.George Murad |

Merchant |

38.Mohammed Ali Darwish |

Merchant |

|

39.Ghassan al-Shallah |

Merchant |

40.Nasouh Sairawan |

Merchant |

|

41.Mousan Nahas |

Merchant |

42.Anwar al-Shammout |

Owner of Sham Wings Co. |

|

43.Mounir Bitar |

Merchant |

44.Bashar al-Nouri |

Merchant |

|

45.Abdullah Natur |

Merchant |

46.Sawsan al-Halabi |

Director of a construction company |

|

47.Tony Bender |

Merchant |

48.Manaf al-Ayashi |

Foodco for Food Industries |

|

49.Maysan Dahman |

Merchant |

50.Khaled al-Tahawi |

Merchant |

|

51.Samer Alwan |

Blue Planet Energy Co. |

52.Saied Hamidi |

Oil and gas sector |

|

53.Roba Minqar |

Clothing industry |

54.Randa Sheikh |

Clothing industry |

|

55.Harout Dker-Mangi |

Merchant |

56.Alya Minqar |

Merchant |

Iran’s Role in Key Sectors

Iran seeks to obtain lucrative investment opportunities in different sectors of the Syrian economy, whether through tenders or monopolies. The main sectors in which Iran is trying to get full access are: agriculture, tourism, industry, reconstruction, and private security.

Agriculture

- Iran’s ability to match Russia’s investments in the Syrian agricultural sector has been significantly limited by the international sanctions imposed upon it. Since 2013 Iran has extended Syria two credit lines with the total value of USD 4.6 billion, aimed mostly at agriculture. Here is a list of Iranian investments in the sector:

- Supply of wheat since 2015 through the Safir Nour Jannat company"سفیر نور جنت".

- An agreement with the Syrian government to establish a joint company to export surplus Syrian agricultural products.

- An investment of USD 47 million for the second phase of implementation of the Iranian credit line to establish a plant to produce animal food, vaccines, and poultry products.

- A contract to build five mills in Syria at a cost of US 82 million in the provinces of Suweida and Daraa.

- A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Syrian General Organization of Sugar (Sugar Corporation) to establish a sugar mill and a sugar refinery in Salha in Hama in 2018.

- A 2018 MOU between the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Agriculture and the Iranian companies Nero and ITM for the import and distribution of 3,000 tractors.

Tourism

The tourism sector is considered one of the most vital sectors in the Syrian economy: it constituted a 14.4 percent share of Syria’s GDP in 2011 (US 64 billion). It has of course been heavily affected by the war, and tourism revenues decreased from SYP 297 billion (around USD 577 million) in 2010 to SYP 17 billion (around USD 33 million) in 2015, while tourism infrastructure suffered a loss of nearly SYP 14 billion (around USD 27 million) over that same period.

Tehran’s investment in Syria’s the tourism sector has been mostly in religious tourism. For instance, the Syrian Minister of Tourism signed a MOU with the Iranian Hajj Organization in 2015 to bring Iranians and others into Syria for religious tours. There are now estimated to be 225,000 religious tourists from Iran, Iraq, and the Gulf countries visiting Syria each year, and they bring in around SYP two billion (around USD 3.9 million) in revenue.

Industry

The industrial sector contributed 19 percent of Syria’s GDP in 2011, and has suffered losses estimated at USD 100 billion during the war. Iran has several industrial facilities in Syria. These are concentrated in the automobile sector, where they include the Syrian-Iranian International Motor Company and Siamco. Iran has also invested in the glass industry in Adra industrial city. The Iranian Saipa group announced a growth in sales of 11 percent in 2017 in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Azerbaijan. Car sales in Syria reached a significant level: although it was a third of 2018 sales in Iraq so far, 50,000 cars were sold in Syria last year.

Iran has tried to obtain contracts from the Syrian government in the industrial sector, and a number of MOUs have been signed. They include:

- A 2017 MOU between the Iranian company Bihin Ghostar Persian and General Organization for Engineering Industries to rehabilitate several companies: General Company for Metallic Industries–Barada (located in al-Sabinahis a town in southern Syria, administratively part of the Rural Damascus Governorate), SYRONICS (located in Damascus) and the battery factory in Aleppo.

- A 2017 MOU between the Syrian Cement and Building Materials Company in Hama and the Yasna Trading Company of Iran for the supply of spare parts.

In 2018, the Syrian-Iranian Business Council submitted a proposal for the participation of Iranian companies in the rehabilitation of Syria’s public industrial sector. In addition, the Iranian Ministry of Industry has expressed a wish to establish a cement production company in Aleppo as part of the second phase of implementation of the Iranian credit line.

Reconstruction and Infrastructure

The construction sector contributed 4.2 percent of Syria’s GDP in 2011 and then suffered a losses of USD 27 billion over the next six years. Syrian infrastructure has taken a similarly heavy hit as a result of the conflict, with losses valued at around at USD 33 billion, including over three million destroyed houses or housing units.

Iran’s interests in reconstruction—as with tourism—have a religious tinge and are mainly focused on the areas around sacred Shi’a shrines. For instance, Iran has been asking the Syrian regime for large concessions in Daraya, the old city of Damascus, Sayida Zainab, and Aleppo. Thus far Iran has mostly relied on Syrian intermediaries to purchase real estate, businessmen such as Bashar Kiwan, Mazen al-Tarazi, Mohammad Jamul, Saeb Nahas, Muhammad Abdul Sattar Sayyid, Daas Daas, Firas Jahm, Nawaf al-Bashir, and Mohammad al-Masha'li. Tehran has also relied on Syrian associations such as Jaafari, Jihad al-Binaa, the al-Bayt Authority, and “the Committee for the Reconstruction of the Holy Shrines" to expand and acquire new land in or near the holy sites in Damascus, Deir Ezzor, and Aleppo.

Sanctions against Syria and their Effect on Iran

The ongoing conflict in Syria has prompted international outcry and condemnation, as well as a long list of "red lines" and sanctions. The sanctions currently in place against Syria include an oil embargo, restrictions on certain investments, a freeze of the Syrian central bank's assets within the European Union, and export restrictions on equipment and technology that might be used for repression of Syrian civilians.

The problem with the sanctions on Syria is that they are ill suited to address the situation, in which sanctions are unlikely to work due to the ongoing war. The EU took significant steps very early in the Syrian conflict, essentially deploying its entire sanctions toolbox in less than one year, in contrast to its more common step-by-step sanctions approach. After a few years, the EU realized that this approach was rushed and ineffective and was forced to backtrack on some measures. This learning process showed the EU that an arms embargo is not necessarily the best first way to address a conflict situation.

Appendix

Syrian Companies Affiliated with Iran

| Name | Arabic Name | Main Activity | Agreement |

|

Abdul Rahim & Fawzi Rahal Co. |

شركة عبد الرحيم وفوزي رحال | معمل مواد بناء، تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير | حماة/طيبة الإمام، سوريا. |

| Ebdaa Development & Investment Co. | شركة إبداع للتطوير والاستثمار | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير | ريف دمشق |

|

Development Co. for Oil Services |

شركة التنمية لخدمات النفط | الخدمات النفطية | ------ |

| Obeidi for Construction & Trade | شركة عبيدي وشريكه للتجارة والمقاولات | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، المقاولات | فندق الداما روز بدمشق |

| Talaqqi Company | شركة تلاقي | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، مستحضرات التجميل | دمشق، كفرسوسة، عقار رقم 2463/ 87 |

| Nagam al-Hayat Company | شركة نغم الحياة | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، الخدمات الاستشارية | ريف دمشق، يلدا/ دف الشوك/ العقار رقم 507 |

| IBS for Security Services | ---- | --- | --- |

| Al-Hares for Security Services | شركة الحارس للخدمات الأمنية | خدمات الأمن والحماية الشخصية | دمشق |

| Mobivida L.L.C | شركة موبي فيدا | تجارة الأجهزة الإلكترونية، الهواتف المحمولة والإكسسوار، وتطوير خدمات الهواتف والإنترنت | دمشق |

| Al-Mazhor Company for Construction | شركة المظهور التجارية | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، المقاولات | دير الزور |

| Al Najjar & Zain Travel & Tourism Company | شركة النجار وزين" للسياحة والسفر | السياحة الدينية | نبل، مقابل مستوصف نبل عبارة الضرير / محافظة حلب |

Top Syrian Businessmen Affiliated with Iran

| Under EU Sanctions? | Under U.S. Sanctions? | Visited Abu Dahbi(UAE) in Jan 2019? | Main Position | Closeness of Relationship with Iran | Name in Arabic | Name |

| - | Yes | Yes | Secretary-General of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | High | محمد حمشو | Mohammad Hamsho |

| - | - | - | Member of Syrian Parliament | High | حسين رجب | Hussein Ragheb |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | حسان زيدو | Hassan Zaidou |

| - | Yes | Yes | Member of Syrian Parliament | High | محمد خير | Muhammad Kheir Suriol |

| - | Yes | Yes | Member of Syrian Exporters Union | High | إياد محمد | Iyad Muhammad |

| - | Yes | Yes | Manager of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | High | فراس جيكلي | Firas Jijkli |

| - | - | - | Chairman of the Supreme Committee for Investors in the Free Zone | High | فهد درويش | Fahd Darwish |

| - | - | - | Syrian Ambassador to Iran | High | عدنان محمود | Adnan Mahmoud |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Medium | عامر خيتي | Amer Khiti |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | علاء الدين خير بيك | Alla Ed din Khair Bik |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Low | جورج مراد | George Murad |

| - | Businessman | Low | منير بيطار | Munir Bitar | ||

| Yes | Yes | - | Works in SDF-controlled area and has relationship with Samir al-Foz | High | محمد القاطرجي | Mohamed al-Qtrji |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | علي كامل | Ali Kamil |

| - | - | Yes | Al-Matin Group General Manager | Medium | لبيب إخوان | Labib Ikhwan |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | سامر علوان | Samir Alwan |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Medium | ناهد مرتضى | Nahid Murtda |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Medium | مصان النحاس | Musan al-Nahas |

| - | - | Yes | Businessman | High | ربى منقار | Ruba Munqar |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Low | هاروت ديكرمنيجان | Harot Dikrmnjyan |

Dr. Ammar Kahf, Commented on latest developments in southern Syria

On the 25th of July, Dr. Ammar Kahf, the executive director of the Omran, commented on latest developments in southern Syria to USA Today, by stating that the regime’s territorial gains in Daraa has put Iran and Hezbollah closer to being a threat to Israel and regional powers.

This development will increase the likelihood of greater conflict in the Middle East. Developments in Daraa are also signs of a new era in the Syrian conflict, where domestic actors have largely disappeared and given way to international and non-state actors using Syria for their own agenda.

Dr. Kahf has stated that “The story of the armed Syrian opposition is over, Iran and Hezbollah are much stronger today than a month ago and closer to the southern front. I think this (Syrian conflict) will continue to escalate.”

Special thanks to the co-writers of the Article, Jacob Wirtschafter and Gilgamesh Nabeel.

Source: https://usat.ly/2NPpBc6

TRT World Interview with Ammar Kahf about cessation deal reached by US and Russia

Dr. Ammar Kahf Talks about cessation deal reached by US and Russia

Geopolitical Realignments around Syria: Threats and Opportunities

Abstract: The Syrian uprising took the regional powers by surprise and was able to disrupt the regional balance of power to such an extent that the Syrian file has become a more internationalized matter than a regional one. Syria has become a fluid scene with multiple spheres of influence by countries, extremist groups, and non-state actors. The long-term goal of re-establishing peace and stability can be achieved by taking strategic steps in empowering local administration councils to gain legitimacy and provide public services including security.

Introduction

Regional and international alliances in the Middle East have shifted significantly because of the popular uprisings during the past five years. Moreover, the Syrian case is unique and complex whereby international relations theories fall short of explaining or predicting a trajectory or how relevant actors’ attitudes will shift towards the political or military tracks. Syria is at the center of a very fluid and changing multipolar international system that the region has not witnessed since the formation of colonial states over a century ago.

In addition to the resurrection of transnational movements and the increasing security threat to the sovereignty of neighboring states, new dynamics on the internal front have emerged out of the conflict. This commentary will assess opportunities and threats of the evolving alignments and provide an overview of these new dynamics with its impact on the regional balance of power.

The Construction of a Narrative

Since March 2011, the Syrian uprising has evolved through multiple phases. The first was the non-violent protests phase demanding political reforms that was responded to with brutal use of force by government security and military forces. This phase lasted for less than one year as many soldiers defected and many civilians took arms to defend their families and villages. The second phase witnessed further militarization of civilians who decided to carry arms and fight back against the aggression of regime forces towards civilian populations. During these two phases, regional countries underestimated the security risks of a spillover of violence across borders and its impact on the regional balance of power. Diplomatic action focused on containing the crisis and pressuring the regime to comply with the demands of the protestors, freeing of prisoners, and amending the constitution and several security based laws.

On the other hand, the Assad regime attempted to frame a narrative about the uprising as an “Islamist” attempt to spread terrorism, chaos and destruction to the region. Early statements and actions by the regime further emphasized a constructed notion of the uprising as a plot against stability. The regime took several steps to create the necessary dynamics for transnational radical groups (both religious and ethnic based) to expand and gain power. Domestically, it isolated certain parts of Syria, especially the countryside, away from its core interest of control and created pockets overwhelmed by administrative and security chaos within the geography of Syria where there is a “controlled anarchy”. It also amended the constitution in 2012 with minor changes, granted the Kurds citizenship rights, abolished the State Security Court system but established a special terrorism court that was used for protesters and activists. The framing of all anti-regime forces into one category as terrorists was one of the early strategies used by the regime that went unnoticed by regional and international actors. At the same time, in 2011 the regime pardoned extremist prisoners and released over 1200 Kurdish prisoners most of whom were PKK figures and leaders. Many of those released later took part in the formation of Jabhat al-Nusra, ISIS, and YPG forces respectively. This provided a vacuum of power in many regions, encouraging extremist groups to occupy these areas thus laying the legal grounds for excessive use of force in the fight against terrorism.

The third phase witnessed a higher degree of military confrontations and a quick “collapse” of the regime’s control of over 60% of Syrian territory in favor of revolutionary and opposition forces. Residents in 14 provinces established over 900 Local Administration Councils between 2012 and2013. These Councils received their mandate and legitimacy by the consensus or election of local residents and were tasked with local governance and the administration of public services. First, the Syrian National Council, then later the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces were established as the official representative of the Syrian people according to the Friends of Syria group. The regime resorted to heavy shelling, barrel bombing and even chemical weapons to keep areas outside of its control in a state of chaos and instability. This in return escalated the level of support for revolutionary forces to defend themselves and maintain the balance of power but not to expand further or end the regime totally.

During this phase, the internal fronts witnessed many victories against regime forces that was not equally reflected on the political progress of the Syria file internationally. International investment and interference in the Syrian uprising increased significantly on the political, military and humanitarian levels. It was evident that the breakdown of the Syrian regime during this phase would threaten the status quo of the international balance of power scheme that has been contained through a complex set of relations. International diplomacy used soft power as well as proxy actors to counter potential threats posed by the shifting of power in Syria. Extremist forces such as Jabhat al-Nusra, YPG and ISIS had not yet gained momentum or consolidated territories during this phase. The strategy used during this phase by international actors was to contain the instability and security risk within the borders and prevent a regional conflict spill over, as well as prevent the victory of any internal actor. This strategy is evident in the UN Security Council Resolution 2042 in April 2012, followed by UNSCR 2043, which call for sending in international observers, and ending with the Geneva Communique of June 2012. The Geneva Communique had the least support from regional and international actors and Syrian actors were not invited to that meeting. It can be said that the heightened level of competition between regional and international actors during this phase negatively affected the overall scene and created a vacuum of authority that was further exploited by ISIS and YPG forces to establish their dream states respectively and threaten regional countries’ security.

The fourth phase began after the chemical attack by the regime in August of 2013 where 1,429 victims died in Eastern Damascus. This phase can be characterized as a retreat by revolutionary military forces and an expansion and rise of transnational extremist groups. The event of the chemical attack was a very pivotal moment politically because it sent a strong message from the international actors to the regional actors as well as Syrian actors that the previous victories by revolutionary forces could not be tolerated as they threatened the balance of power. Diplomatic talks resulted in the Russian-US agreement whereby the regime signed the international agreement and handed over its chemical weapons through an internationally administered process. This event was pivotal as it signified a shift on the part of the US away from its “Red Line” in favor of the Russian-Iranian alignment, which perhaps was their first public assertion of hegemony over Syria. The Russian move prevented the regime’s collapse and removed the possibility of any direct military intervention by the United States. It is at this point that regional actors such as Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia began to strongly promote a no-fly zone or a ‘safe zone’ for Syrians in the North of Syria. During this time, international actors pushed for the first round of the Geneva talks in January 2014, thus giving the Assad regime the chance to regain its international legitimacy. Iran increased its military support to all of Hezbollah and over 13 sectarian militias that entered Syria with the objective of regaining strategic locations from the opposition.

The lack of action by the international community towards the unprecedented atrocities committed by the Syrian regime, along with the administrative and military instability in liberated areas created the atmosphere for cross-border terrorist groups to increase their mobilization levels and enter the scene as influential actors. ISIS began gaining momentum and took control over Raqqa and Deir Azzour, parts of Hasaka, and Iraq. On September 10, 2014, President Obama announced the formation of a broad international coalition to fight ISIS. Russia waited on the US-led coalition for one year before announcing its alliance to fight terrorism known as 4+1 (Russia, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Hezbollah) in September 2015. The Russian announcement came at the same time as ground troops and systematic air operations were being conducted by the Russian armed forces in Syria. In December 2015, Saudi Arabia announced the formation of an “Islamic Coalition” of 34 largely Muslim nations to fight terrorism, though not limited to ISIS.

These international coalitions to fight terrorism further emphasized the narrative of the Syrian uprising which was limited to countering terrorism regardless of the internal outlook of the agency yet again confirming the regime’s original claims. As a result, the Syrian regime became the de facto partner in the war against terrorism by its allies while supporters of the uprising showed a weak response. The international involvement at this stage focused on how to control the spread of ISIS and protect each actor from the spillover effects. The threat of terrorism coupled with the massive refugee influx into Europe and other parts of the world increased the threat levels in those states, especially after the attacks in the US, France, Turkey and others. Furthermore, the PYD-YPG present a unique case in which they receive military support from the United States and its regional allies, as well as coordinate and receive support from Russia and the regime, while at the same time posing a serious risk to Turkey’s national security. Another conflictual alliance is that of Baghdad; it is an ally of Iran, Russia and the Syrian regime; but it also coordinates with the United States army and intelligence agencies.

The allies of the Assad regime further consolidated their support of the regime and framing the conflict as one against terrorism, used the refugee issue as a tool to pressure neighboring countries who supported the uprising. On the other hand, the United States showed a lack of interest in the region while placing a veto on supporting revolutionary forces with what was needed to win the war or even defend themselves. The regional powers had a small margin between the two camps of providing support and increasing the leverage they have on the situation inside Syria in order to prevent themselves from being a target of such terrorism threats of the pro-Iran militias as well as ISIS.

In Summary, the international community has systematically failed to address the root causes of the conflict but instead concentrated its efforts on the conflict's aftermath. By doing so, not only has it failed to bring an end to the ongoing conflict in Syria, it has also succeeded in creating a propitious environment for the creation of multiple social and political clashes, hence aggravating the situation furthermore. The different approaches adopted by both the global and regional powers have miserably failed in re-establishing balance and order in the region. By insisting on assuming a conflictual stance rather than cooperating in assisting the vast majority of the Syrian people in the creation of a new balanced regional order, they have assisted the marginalized powers in creating a perpetual conflict zone for years to come.

Security Priorities

The security priorities of regional and international actors have been in a realignment process, and the aspirations of regional hegemony between Turkey, Arab Gulf states, Iran, Russia and the United States are at odds. This could be further detailed as follows:

• The United States: Washington’s actions are essentially a set of convictions and reactions that do not live up to its foreign policy frameworks. The “fighting terrorism” paradigm has further rooted the “results rather than causes” approach, by sidelining proactive initiatives and instead focusing on fighting ISIS with a tactical strategy rather than a comprehensive security strategy in the region.

• Russia: By prioritizing the fight against terror in the Levant, Moscow gained considerable leverage to elevate the Russian influence in the Arab region and an access to the Mediterranean after a series of strategic losses in the Arab region and Ukraine. Russia is also suffering from an exacerbating economic crisis. Through its Syria intervention, Russia achieved three key objectives:

1. Limit the aspirations and choices of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey in the new regional order.

2. Force the Iranians to redraft their policies based on mutual cooperation after its long control of the economic, military and political management of the Assad regime.

3. Encourage Assad’s allies to rally behind Russia to draft a regional plan under Moscow’s leadership and sphere of influence.

• Iran: Regionally, Iran intersects with Washington and Moscow’s prioritizing of fighting terrorism over dealing with other chronic political crises in the region. It is investing in fighting terrorism as a key approach to interference in the Levant. The nuclear deal with Iran emerged as an opportunity to assign Tehran as the “regional police”, serving its purpose of exclusively fighting ISIS. The direct Russian intervention in Syria resulted in Iran backing off from day-to-day management of the Syrian regime’s affairs. However, it still maintains a strong presence in most of the regional issues – allowing it to further its meddling in regional security.

• Turkey: Ankara is facing tough choices after the Russian intervention, especially with the absence of US political backing to any solid Turkish action in the Levant. It has to work towards a relative balance through small margins for action, until a game changer takes effect. Until then, Turkey’s options are limited to pursuing political and military support of the opposition, avoiding direct confrontation with Russia and increasing coordination with Saudi Arabia to create international alternatives to the Russian-Iranian endeavors in the Levant. Turkey’s options are further constrained by the rise of YPG/PKK forces as a real security risk that requires full attention.

• Saudi Arabia: The direct Russian intervention jeopardizes the GCC countries’ security while it enhances the Iranian influence in the region, giving it a free hand to meddle in the security of its Arab neighbors. With a lack of interest from Washington and the priority of fighting terror in the Levant, the GCC countries are only left with showing further aggression in the face of these security threats either alone or with various regional partnerships, despite US wishes. One example is the case in Yemen, where they supported the legitimate government. Most recently in Lebanon, it cut its financial aid and designated Hezbollah as a terrorist organization. Riyadh is still facing challenges of maintaining Gulf and Arab unity and preventing the plight of a long and exhausting war.

• Egypt: Sisi is expanding Egyptian outreach beyond the Gulf region, by coordinating with Russia which shares Cairo’s vision against popular uprisings in the Arab region. He also tries to revive the lost Egyptian influence in Africa, seeking economic opportunities needed by the deteriorating Egyptian economic infrastructure.

• Jordan: It aligns its priorities with the US and Russia in fighting terrorism, despite the priorities of its regional allies. Jordan suffices with maintaining security to its southern border and maintaining its interests through participating in the so-called “Military Operation Center - MOC”. It also participates and coordinates with the US-led coalition against terrorism.

• Israel: The Israeli strategy towards Syria is crucial to its security policy with indirect interventions to improve the scenarios that are most convenient for Israel. Israel exploits the fluidity and fragility of the Syrian scene to weaken Iran and Hezbollah and exhaust all regional and local actors in Syria. It works towards a sectarian or ethnic political environment that will produce a future system that is incapable of functioning and posing a threat to any of its neighbors.

During the recent Organization of Islamic Cooperation conference in Istanbul the Turkish leadership criticized Iran in a significant move away from the previous admiration of that country but did not go so far as cutting off ties. One has to recognize that political realignments are fluid and fast changing in the same manner that the “black box” of Syria has contradictions and fragile elements within it. The new Middle East signifies a transitional period that will witness new alignments formulated on the terrorism and refugee paradigms mentioned above. Turkey needs Iran’s help in preventing the formation of a Kurdish state in Syria, while Iran needs Turkey for access to trade routes to Europe. The rapprochement between Turkey and the United Arab Emirates as well as other Gulf States signifies a move by Turkey to diffuse and isolate polarization resulting from differences on Egypt and Libya and building a common ground to counter the security threats.

Opportunities and Policy Alternatives

The political track outlined in UNSC 2254 has been in place and moving on a timeline set by the agreements of the ISSG group. The political negotiations aim to resolve the conflict from very limited angles that focus on counter terrorism, a permanent cease-fire, and the maintenance of the status quo in terms of power sharing among the different groups. This political track does not resolve the deeper problems that have caused instability and the regional security threat spillover. This track does not fulfill the security objectives sought by Syrian actors as well as regional countries.

Given the evolving set of regional alignments that has struck the region, it is important to assess alternative and parallel policies to remain an active and effective actor. It is essential to look at domestic stabilizing mechanisms and spheres of influence within Syria that minimize the security and terrorism risks and restore state functions in regions outside of government control. Local Administration Councils (LAC) are bodies that base their legitimacy on the processes of election and consensus building in most regions in Syria. This legitimacy requires further action by countries to increase their balance of power in the face of the threat of terrorism and outflow of refugees.

A major priority now for regional power is to re-establish order and stability on the local level in terms of developing a new legitimacy based on the consensus of the people and on its ability to provide basic services to the local population. The current political track outlined by the UNSC 2254 and the US/Russian fragile agreements can at best freeze the conflict and consolidate spheres of influence that could lead to Syria’s partition as a reality on the ground. The best scenario for regional actors at this point in addition to supporting the political track would be to support and empower local transitional mechanisms that can re-establish peace and stability locally. This can be achieved by supporting and empowering both local administration councils and civil society organizations that have a more flexible work environment to become a soft power for establishing civil peace. Any meaningful stabilization project should begin with the transitioning out of the Assad regime with a clear agreed timetable.

Over 950 Local Councils in Syria were established during 2012-2013, and the overwhelming majority were the result of local electing of governing bodies or the consensus of the majority of residents. According to a field study conducted by Local Administration Councils Unit and Omran Center for Strategic Studies, at least 405 local councils operate in areas under the control of the opposition including 54 city-size councils with a high performance index. These Councils perform many state functions on the local level such as maintaining public infrastructure, local police, civil defense, health and education facilities, and coordinating among local actors including armed groups. On the other hand, Local Councils are faced with many financial and administrative burdens and shortcomings, but have progressed and learned extensively from their mistakes. The coordination levels among local councils have increased lately and the experience of many has matured and played important political roles on the local level.

Regional powers need domestic partners in Syria that operate within the framework of a state institution not as a political organization or an armed group. Local Councils perform essential functions of a state and should be empowered to do that financially but more importantly politically by recognizing their legitimacy and ability to govern and fill the power vacuum. The need to re-establish order and peace through Local Councils is a top priority that will allow any negotiation process the domestic elements of success while achieving strategic security objectives for neighboring countries.

Published In The Insight Turkey, Spring 2016, Vol. 18, No. 2

TRT World - Interview with Dr. Ammar Kahf on Kerry's Meetings in Geneva

Dr. Ammar Talks About Kerry's Role in Reaching a Politial Solution in Syria and De Mistrua's Meeting with Kerry in Geneva