Media Appearance

Syria's Landscape in 2023: Unrest and the False Sense of Stability

Introduction

Since the onset of the Syrian conflict, marked by a scenario of geographical entrenchment, it has witnessed a plethora of interactions and developments. These range from the structural reorganization of local actors to shifts in the global security and political landscape. The security dynamics in play challenge established boundaries and may lead to either the contraction or expansion of influence zones. Expanding parties will find opportunities to bolster their negotiating positions within the context of political settlements. The political consequences of these dynamics warrant continuous analysis and anticipation, especially considering their implications for international events, including the February earthquake and the Israeli offensive on Gaza.

This report delves into the political, security, and economic trends in Syria, highlighting the strategies of both local and international stakeholders (1).

Between International Isolation and Normalization: A Vague Arab Initiative

Throughout 2022 and 2023, efforts by Iran and Russia to facilitate the Syrian regime's re-engagement with regional countries and its re-entry onto the international stage have intensified. This includes collaboration with Turkey through a tripartite track involving Moscow, Damascus, and Ankara, which Tehran later joined, potentially extending to Arab nations. Despite enhanced security coordination, this path remains fraught with uncertainty due to conflicting interests, such as the regime's reluctance to afford electoral advantages to the Turkish president before elections and disputes over the Turkish military presence in Syria.

The thaw in relations between Arab nations and the Syrian regime has made significant strides, aligning with a regional inclination towards containing conflicts and restoring stability, albeit at the expense of comprehensive solutions. This trend is reinforced by the Arab-Turkish détente, the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement, and steps towards Arab-Israeli normalization.

The February 2023 earthquake in Turkey and Syria catalyzed a political shift that favored the regime by enabling it to solicit international aid and economic support while demanding sanctions relief. The regime's dominance over humanitarian aid delivery points, despite opposition from the United Nations and several countries, highlighted the challenges in aid distribution. This scenario also provided countries seeking normalization with the regime, driven by the “Arab Initiative,” which advocates for dialogue with Assad to achieve a comprehensive solution. This wave of Arab openness began with security and ministerial exchanges leading to the reopening of diplomatic missions in Arab capitals and culminating in Bashar al-Assad's invitation to the Jeddah summit and the restoration of Syria's Arab League membership. The “Arab Ministerial Liaison Committee,” formed under this initiative, focuses on security, counter-terrorism, and humanitarian issues, alongside advancing the political process in accordance with UN Resolution 2254. However, the impact of the Arab initiatives was limited by a lack of strategic vision and effective leverage over the Syrian regime, leading to the suspension of committee meetings due to Arab dissatisfaction with the regime's inaction. This shift towards bilateral engagements has favored the regime, enabling it to sidestep significant commitments while alleviating its isolation.

The year 2023 marked a turning point in the regime's diplomatic engagements, despite opposition from Western nations to normalization efforts. Western responses, including legal actions against Assad for war crimes, highlight the challenges of any normalization attempt, underscoring the complexities of reintegrating Syria into the global community.

A Faltering Political Process and Local Actors Trying to Establish Their Presence

The complexities of the Syrian situation are compounded by the stalled political process, with only the Constitutional Committee remaining active. Despite the stagnation of its proceedings, the committee has been in limbo since its eighth session in mid-2022, obstructing the organization of its ninth session scheduled for July 2023. Efforts by the Arab Liaison Committee to advance the political dialogue have led to the announcement of resumed sessions at the year's end, relocating from Geneva to Amman in response to Russian claims of Geneva's “lack of neutrality.” The regime's stubbornness, its indifference to the Arab initiative, and its refusal to make concessions particularly in light of the Arab rapprochement it perceives as a victory have brought the political process to a crossroads, according to Geir Pedersen.

Two sessions were conducted in the Astana format, with the twentieth potentially being the last in Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan asserts that Astana has fulfilled its aim of gradually ending Syria's regional isolation a view not shared by the trio of involved countries and instead mirrors the regime's preference for a quadripartite path excluding the opposition delegation. The concluding statement emphasized finalizing the normalization roadmap between Turkey and the regime, focusing on the northeast and de-escalation zones, opposing sanctions, broadening humanitarian aid, depoliticizing it, and acknowledging the regime's permission for its entry. This was followed by the twenty-first round on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly, which concluded without a final statement.

The regime faces escalating public unrest due to dissatisfaction with its governance, economic decline in its territories, and rampant chaos and smuggling networks. Assad's indifference was evident in a CNN interview, where he downplayed the Arab initiative's significance, asserting that political relationships are inadequate without substantial support for the Syrian state to control its borders. He insisted that linking early recovery and reconstruction efforts, and thus the returnee issue, to security and political situations is unnecessary, viewing them instead as economic necessities. His continuous emphasis on economic sanctions as a direct crisis cause, coupled with the removal of government subsidies on essential goods, has transformed public frustration into opposition movements in the Sahel, protests in Daraa, and ongoing demonstrations in Suwayda with explicit political demands backed by influential religious and social figures. The regime's attempts to quell public discontent in the Sahel involved replacing the governor, enforcing security control, or manipulating economic networks. In Suwayda, the focus was on preventing the movement's spread beyond the governorate, relying on demonstrators' fatigue and the potential for economic siege if needed. Regarding legislation and laws, the regime abolished the Military Field Court, issued decrees concerning military service, and announced a general amnesty that excludes most political prisoners. These actions are perceived as superficial, intended to appear as “reformist” steps without necessitating real guarantees.

In northwestern Syria, official opposition entities have seen their operational scope diminish due to the political process's deadlock and the regime's recognition as the sole official Syrian representative by several countries. Their activities this year were confined to opening political horizons, diplomatic endeavors following the report condemning the regime's use of chemical weapons in Douma in 2018, support tours for earthquake-affected areas, and limited efforts to curb normalization or advocate for the application of Resolution 2245, restricted to the available margins. Visits aimed at halting military escalation in Idlib were conducted, while the Sweida movement represented a significant opportunity to rejuvenate the issue, albeit not addressed adequately. Internally, opposition groups faced challenges related to their structure, elections, and the circulation of prominent figures among positions, sparking popular discontent. Additionally, the interim government's performance was weak, and the independence of these bodies' decisions was compromised by country-specific determinants.

In northeastern Syria, the Autonomous Administration's efforts were marked by pragmatism. On one hand, it sought to preemptively co-opt opposition forces in anticipation of potential Turkish normalization with the regime at their expense. It collaborated with the Syrian National Alliance Party, which established offices in its territories, and with the National Coordination Body for Democratic Change Forces to form an opposition front endorsing the “National Democratic Change Project.” This initiative, based on five fundamental principles for a successful political resolution involving “national democratic political forces” in accordance with Security Council Resolution 2254, did not alter the administration's stance. Conversely, it expressed willingness to dialogue and cooperate with the regime on its terms, with the potential integration of its forces into the Syrian army under agreeable conditions. However, according to Mazloum Abdi, the regime's rigidity obstructs this possibility. Internally, the Autonomous Administration faced protests concentrated in Deir Ezzor and spreading among Arab tribes in various “civil administrations” regions. Demonstrations were against the SDF's dominion over the area and resources, mismanagement, exclusion of the Arab component, and marginalization of its demands, represented through figures affiliated with the administration. At the Fourth Conference of the SDF, a new council was elected under co-chairmanship, considering tribal balance, represented by “Mahmoud al-Muslat,” with the presence of PYD-endorsed figures and the elimination of the “CEO” role held by Ilham Ahmed since the council's inception in 2015.

The “Democratic Autonomous Administration's social contract in the northern and eastern Syria region” was ratified, designating SDF-controlled areas as a “region” within a confederation, to be followed by general elections in 2024. The contract, more a constitution than a social agreement, was imposed by the ruling party, reflecting its views rather than local perspectives, without consultations representing societal components among local populations. Additionally, the disparity between the articles' text and their implementation, even regarding decentralization a key demand of the Autonomous Administration remains unenforced in its centrally governed areas.

The Gaza War and Its Regional Implications: Open Possibilities

Operation “Al-Aqsa Flood” presented an unexpected turn of events, causing disarray locally, regionally, and internationally. Contrary to the regional trend of containing conflicts and mitigating issues irrespective of solutions, the operation reignited concerns over the potential for war expansion, the reemergence of non-state actors, the advent of new organizations, and the ensuing humanitarian crisis requiring decisive regional responses.

In Syria, the Gaza conflict raised fears of escalation spreading to Syrian or Lebanese territories or drawing any party into participation, particularly with Iran and its affiliated militias and thus the regime considered part of the “resistance axis.” However, Iran's stance remained detached, limiting its involvement to statements, threats, and announcing support for adversarial movements such as the Houthis in Yemen and Hezbollah, which satisfied itself with ineffective missile strikes, alongside a few missiles launched from the Golan for appearances. The regime adhered to Iran's position, responding to Israeli threats with cautious, disciplined statements regarding the Palestinian cause's legitimacy, brutal aggression, and a conspiring world. It notably disregarded “Hamas,” maintaining a steadfast stance despite normalized relations, viewing it as unrepresentative of the broader issue. The regime's participation in the Riyadh summit on Gaza was confined to delivering a speech without objecting to any final statement items, including the two-state solution, civilian casualties on both sides, and establishing normal relations with Israel. Other countries, such as Tunisia, Iraq, and Algeria, expressed reservations, while Iran objected to recognizing the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as the sole Palestinian representative. The regime also prevented public demonstrations condemning the war in its territories, deviating from the norm, settling for specific vigils organized by unions under Baath Party and security service supervision, possibly fearing demonstrations could turn against it.

The official opposition's response was characterized as weak, hesitant, and delayed. The coalition issued general statements of solidarity with victims and condemnation of Israeli attacks, particularly following the targeting of the Baptist Hospital, condemned by the interim government. Meanwhile, the negotiating body largely overlooked the conflict, save for a mention in a final statement from its regular Geneva session and a tweet by the body's head. This cautious approach is attributed to apprehension over potential backlash and the loss of Western support the last remaining political backing for the Syrian cause additionally influenced by Hamas's stance, which had recently reestablished relations with the regime. The position of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) was more pronounced at the official level, issuing statements supporting the Palestinian cause without mentioning Hamas, alongside official events and fundraising through endowments. Opposition-controlled areas in northern Aleppo and Idlib witnessed significant public demonstrations in support of the Palestinian cause.

The SDF did not articulate an official stance on the conflict, except for a neutral statement by former SDF executive Ilham Ahmed, expressing solidarity with victims on both sides without taking a definitive stand on the aggression. This was despite the historically pro-Palestinian stance of Kurdish organizations, attributed to concerns over the American ally's position, Hamas's proximity to Turkey, and reluctance to express opinions unrelated to the consolidation of the self-administration project.

The Regime’s Systemic and Functional Security Crises

With the escalation of the Gaza conflict into a pivotal international juncture, its repercussions resonated deeply within the Syrian landscape, primarily serving as a conduit for message exchanges and score-settling between Israel and Iran. Meanwhile, the Syrian regime maintained a cautious distance from the conflict amidst Israeli cautions to Iran about the repercussions of its involvement. In this backdrop, international coalition bases faced recurrent assaults, paralleling a series of attacks by Iranian proxies in the region against US and Israeli interests from Lebanon, Yemen, Iraq, and Syria, including selective strikes targeting southern Syria near the Golan Heights. Concurrently, Israel ramped up its attacks on the infrastructure and command echelons of regime forces and Iranian militias, notably executing the assassination of Reza Mousavi, a leading Iranian official in Syria. This move was part of Israel's strategy to weaken the efforts of Iranian militias to fortify their positions following the assault on Gaza, showcasing their military prowess and readiness across multiple fronts.

Domestically, the Syrian regime's security infrastructure grappled with multiple challenges, including bombings and assassinations in supposedly secure regions, such as the Homs and Damascus countryside. A significant incident was a drone attack on a military academy, claiming the lives of 123 regime personnel, including several brigadier generals. This event highlighted substantial security lapses, challenging the regime's security framework and the air supremacy claimed by Russia and the regime west of the Euphrates, as well as contesting the aerial dominance of regional powers amid the advancing military capabilities of non-state actors utilizing drones in Syria and the wider region.

Within territories under regime control, As-Suwayda governorate witnessed an insurrection and popular movement, posing a severe challenge to the regime's narrative of stability and control. The movement in Suwayda, carrying both national and local dimensions, underscored the governorate's strategic significance owing to its proximity to al-Tanf and its role as a conduit for smuggling operations. The regime's strategy to counter this movement involved demonizing it in the media as separatist or foreign-driven, aiming to isolate it on a national level. Moreover, the regime leveraged the strategy of time, withholding services and exacerbating the already dire living conditions to pressure the movement, while attempting to fragment it by exploiting differences among religious and social factions within Suwayda. Despite the movement's impact being confined primarily to Suwayda, its importance lies in challenging the regime's narrative centered on “minority protection,” emphasizing Suwayda's strategic significance in security discussions, particularly regarding smuggling and its proximity to critical security locales.

The ISIS threat persists despite the assassination of its fourth leader by Turkish intelligence, as the organization continues to pose a security risk in Syria and globally. This is manifested by an escalation in the number and quality of operations it conducts, especially in the last quarter of the past year, leading to a marked Russian air escalation, representing a significant counteraction against the organization in 2023. While Jordan has revised its rules of engagement in response to the escalating threat from drug and arms smuggling networks supported by the regime and Iran along its northern border. This adjustment reflects Jordan's growing concerns over the sheer number of these groups, their technological and military capabilities, and the ineffectiveness of Jordanian dialogue with the regime in securing tangible security outcomes. Jordan, since May, has resorted to force, conducting air raids within Syrian territory, and requested Patriot missile systems from the United States to counter the drone threat.

Beyond the Regime's Control: Attempts at Governance and Resistance

In areas under the Autonomous Administration in northeastern Syria, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) encountered several challenges, notably a tribal uprising following the detention of Abu Khawla, the leader of the Deir Ezzor Military Council. This uprising reflects deep-seated structural problems within the SDF's capacity to assimilate the Arab component and redress tribal grievances due to the dominance of the Workers' Party within the SDF's administration. The absence of American initiative to induce changes within the SDF, along with internal tribal challenges and apprehensions regarding potential encroachment by Iranian militias, collectively shape the future prospects of the tribal movement in the region. Turkey has maintained its aggressive posture towards the PKK, designated as a terrorist organization, especially following an incident in Ankara in October. This prompted Turkey to intensify its aerial bombardments targeting SDF military leadership and infrastructure, highlighting Turkey's strategic reach and its reliance on sophisticated drone technology in its counterterrorism strategy.

In northwestern Syria, Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) has launched an unparalleled campaign of internal arrests, detaining members from its administrative, security, and media wings on charges of espionage for the regime, Russia, or the United States. This move signifies HTS leadership's ongoing efforts to consolidate control and neutralize prominent figures, while also capitalizing on factionalism within areas controlled by the National Army to expand its influence.

The Regime's Economic Policies: Burdening Society and State

In January 2023, the Syrian regime initiated a series of bold economic reforms, characterized by a significant reduction in social support mechanisms, placing an increased burden on the market and exacerbating the poverty and living crisis of its citizens. The commencement of 2023 saw the average cost of living in Syria surge to over 4 million SYP for a family of five, with the number of individuals in need of humanitarian assistance soaring to more than 15 million at the start of the year. The devaluation of the Syrian pound continued, with the exchange rate exceeding 7,500 SYP to the dollar by the end of the previous year and recorded at 6,825 SYP by the end of January 2023. The regime's government increased the price of gasoline, marking the second hike within three weeks amid a significant scarcity of petroleum derivatives. Additionally, the Ministry of Economy raised customs duties on all imports by 15-20%, contributing to increased prices for imported goods.

These trends persisted and even escalated in the following months, with the average living costs for a family of five in Syria reaching more than 10.3 million SYP by August, according to the “Qasioun Newspaper” index, up from 4 million SYP in January. Despite salary increases, the average wages, post-increase, did not surpass 200,000 SYP. The regime's economic policies led to a continuous decline in the value of the Syrian pound, surpassing 15,000 SYP against the dollar, with the central bank pricing the exchange rate for remittances at 10,900 pounds. This ongoing devaluation significantly reduced the citizens' purchasing power, rendering salary increases ineffective and exacerbating the population's poverty and living hardships. These developments also underscore the ineffectiveness of the regime's economic management, which addresses the crisis with unproductive solutions.

A significant and economically indicative trend was the increased rate of merchant emigration, especially among traders from Aleppo and Damascus. This included the relocation of significant gold reserves, estimated at around 300 kilograms (approximately 1% of the country's total gold reserves), by top jewelers including (Bashoura, Said Mansour, and al-Jazmati), who moved their entire stock abroad.

Regarding trade relations between the regime and Arab countries, the regime showed considerable interest in economic openness towards Iraq and Saudi Arabia. The Syrian regime appointed an ambassador to the Arab League and conducted visits to Iraq and Saudi Arabia, agreeing to resume economic cooperation with Arab states. Iraq allowed Syrian trucks to enter its territory again at the beginning of the year following agreements between the Syrian Ministry of Transport and the Iraqi side, leading to a 35% increase in trade between Syria and Iraq. Moreover, Jordanian exports through the Nassib crossing in the previous year, 2022, were 23 times the Syrian exports, which only amounted to $20 million.

On the other hand, the regime allowed merchants to import from Saudi Arabia, signing a contract for sugar imports and working on mechanisms to facilitate the movement of Syrian and Saudi trucks in the coming period. The regime stated that there is “no political objection” to importing goods from Saudi Arabia, permitting the import of sugar, chemicals, and petrochemicals. After a hiatus in investments in Syria since 2011, the regime granted licenses in August to two companies owned by Saudi investors to invest in the phosphate, fertilizer, and cement sectors in Syria. The regime's exports of vegetables and fruits amounted to between 500 to 600 tons, with 90% directed to Saudi Arabia, amid almost daily price hikes in the local market due to production shortages and rising costs of raw materials, including fuel, seeds, transportation, and labor. After potato prices surged by 150% in local markets, the Ministry of Economy halted its export when the price per kilogram reached 5,000 SYP, up from 2,000 SYP per kilogram in August, despite the regime's prior approval to export 40,000 tons of potatoes.

In regard to Iran economic activities in 2023, it didn’t spare no effort in 2023 to increase its influence and consolidate its presence in the Syrian economy, with the Iranian Minister of Roads and Urban Development Mehrdad Bazrpash signing agreements with the Syrian regime during an April visit in various sectors including economy, trade, housing, oil, industry, electricity, transport, and insurance. In addition to scheduled plans for stablishing an oil refinery with a capacity of 140,000 barrels per day, adjacent to the existing refineries in Homs and Baniyas, as announced by the Iranian Oil Minister Jalil Salari, to augment the income of Iranian companies. This plan is alongside numerous others set by Iran in Syria over the past years, though sanctions on the Syrian and Iranian oil sectors stand as barriers to maintaining and implementing oil projects in Syria that could fund the regime.

During a visit by the Governor of the Central Bank of Iran, Mohammad Reza Farzin, to Damascus, both sides agreed on a mechanism for using local currencies in trade exchanges between the two countries and establishing communication channels between the central banks to evade sanctions. In the context of bolstering banking and trade relations and joint investments, the Iranian official mentioned Iran's intention to soon open its first bank in Syria.

In December, a Syrian regime delegation in Tehran, led by Prime Minister Hussein Arnous, signed memorandums of understanding in banking, finance, tourism, sports, culture, reconstruction, trade, and the operation of power plants in Syria by Iranian investors. They agreed on zeroing customs duties between the two countries, and the Syrian Central Bank governor discussed with his Iranian counterpart ways to develop trade relations, establish mechanisms for trade exchange in local currencies, and set up a joint bank in Syria. This also includes executing a series of projects by the “Bonyad Mostazafan” foundation, Iran's second-largest investment entity, encompassing 200 factories and financial companies, including a bank and real estate companies, which is internationally sanctioned and directly affiliated with the Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. This step aims to fulfill Tehran's goal of acquiring a broader share in the Syrian economy.

Aftermath of the February Earthquake: An Alarming Economic Scene

February 2023 witnessed a devastating earthquake that struck northern Syria and southern Turkey on February 6th, affecting over 1.8 million people in northwestern Syria. The catastrophe resulted in the loss of 4,256 civilians' lives, approximately 12,000 injuries, and displaced 300,000 individuals, with children, women, and special needs cases constituting more than 65% of the displaced. The economic losses amounted to $1.95 billion, affecting the public and private sectors and other facilities, while over 13,000 families lost their income sources. The earthquake damaged infrastructure, including 433 schools, 73 medical facilities, and 136 housing units, with over 2,000 buildings collapsing immediately.

The Assad regime saw the earthquake disaster as a lifeline to boost economic activity within its control zones, launching donation campaigns and “for earthquake victims” and receiving financial donations from industrialists in Homs and businessmen estimated at 1.5 billion SYP. Additionally, pro-regime parties and groups exploited the earthquake to campaign for the flow of aid to the Syrian regime and lifting sanctions imposed on it due to crimes committed over the past decade, which restricted its economic activities. The Cross-Border Humanitarian Fund for Syria announced the release of at least $50 million for humanitarian response following the disaster, and the Omran Center for Strategic Studies reported that 23 countries and the United Nations sent approximately 11,772 tons of humanitarian and logistical aid through regime-controlled airports in Damascus, Aleppo, and Latakia. The regime received about 435 trucks of aid from several Arab countries through the Arbaeen, Jadidah, Nassib, and al-Bukamal crossings.

In opposition-held areas in the countryside of Aleppo and Idlib, the region significantly suffered from a lack of aid in the first week of the disaster. The Omran Center for Strategic Studies reported that around 590 trucks, carrying between 5,300 and 7,000 tons of aid, entered from the Bab al-Hawa, al-Salam, and al-Raee crossings between February 9 and 27.

In northeastern Syria, the Autonomous Administration attempted to exploit the earthquake's aftermath to make a breakthrough in its relationship with the opposition by offering a convoy of fuel and medical supplies to the affected areas, which the opposition rejected for reasons including the Administration's insistence on branding the aid with its logos. The Administration announced the opening of all its crossings for humanitarian aid coming from outside its control areas to reach the earthquake victims. In the context of civil and popular initiatives, several civil organizations and social activities in northeastern Syria launched public campaigns to collect financial and in-kind donations from the region's residents and send them to the victims in the affected areas, including the “Tribal Solidarity” campaign, which collected 146 trucks loaded with clothing, household furnishings, food, baby milk, and medical supplies, along with financial donations, and entered the affected areas in northwestern Syria. However, the region later saw a clear decline in humanitarian response operations for the earthquake victims by 35% compared to the end of February, leaving thousands of families unable to secure even one meal a day amidst rising poverty rates and decreasing purchasing power among the population.

Methods of addressing economic impacts varied across influence zones, including periodic salary increases for employees, decisions to regulate markets, and increased control by de facto authorities over economic life. In terms of economic governance, the Autonomous Administration issued two laws to regulate exchange and remittance businesses and the trade and manufacturing of precious metals. The Administration also prohibited the export of dollars from its areas to those controlled by the regime and the opposition, as part of measures to restrict money transfers in and out of its areas, indicating increased financial or cash outflows abroad through smuggling operations, the rise of illegal activities, money laundering, tax evasion, and the Administration's preventive stance towards the available foreign currency reserves.

The Salvation Government in Idlib established a commercial court headquartered in Sarmada city, aimed at addressing disputes and cases arising between traders registered with the chambers of commerce. The court operates in 8 specializations, including intellectual property, bankruptcy, and disputes related to commercial papers, exchange, currencies, commercial remittances, and banking activities. This court's establishment follows a series of decisions, including one to regulate contracting procedures, contributing to the institutionalization and governance of the economy in the region, especially given the multitude of commercial activities and complex trade relations with the existence of the Bab al-Hawa crossing linking Idlib to Turkey. The Salvation Government's efforts aim to attract investors to its controlled areas. While the Interim Government also focused on encouraging investments in its controlled areas, with the Ministry of Finance and Economy announcing the launch of the first Investment Conference in cooperation with Aleppo University in the liberated areas, the Economists Syndicate, and the 2020IDEA foundation. The conference aims to economically develop the liberated areas, improve living standards, increase job opportunities, and resume the entry of UN aid into northwestern Syria through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing with Turkey.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Syrian scene remains largely static, with no significant changes expected from international actors or de facto authorities. Despite the regime's political breakthrough following regional normalization and partial restoration of international legitimacy, significant challenges persist, including maintaining influence, navigating ongoing negotiations without concessions, and addressing deteriorating living conditions that could lead to potential unrest. The dynamic security landscape, further complicated by the Gaza war's implications, highlights the intricate interplay between regional actors, local dynamics, and the enduring threats to national security for countries like Turkey and Jordan. This complex scenario emphasizes the evolving nature of the conflict, strategic shifts among local actors, and the continuous need for adaptation to both internal and external pressures.

([1]) For access to the Omran Center's monthly briefings during 2023, see the following link: https://bit.ly/3VXM9hi

Conference: Playground for foreign powers: MENA region as a target to foreign intervention

In Pretoria 8-9 October 2019. Omran Center Senior Fellow Dr. Sinan Hatahet participated at the annual international conference organized by Afro-Middle East Centre entitled "Playground for foreign powers: MENA region as a target to foreign intervention".

Hezbollah’s International Financing Operation: From Economic Resistance to Criminal Endeavor

Executive Summary

-

Hezbollah has been heavily reliant on Iran’s generosity, to fund its operation, with Tehran’s aid estimated at around USD 700 million in 2008.

-

The organization has nonetheless increasingly diversified its revenue base, getting involved in drug trade, counterfeiting operations, arms trade and money laundry operations, in the US, the Caribbean, Europe, and Africa.

-

Hezbollah has also been involved in licit ventures such as construction and various trading businesses in Africa.

-

In Lebanon and Israel, Hezbollah has mostly relied on dealing drugs to extort information from Israeli military or recruit new agents. However in recent years, more and more Hezbollah members has been involved in drug and other illicit trade scandals, as well as racketeering schemes, the organization having difficulty in cracking down on corruption.

Introduction

Originally, a southern Lebanese group focused on fighting the Israeli occupation (1982 to 2000), Hezbollah has morphed into a powerful paramilitary force with military activities throughout the Middle East region. Today, the Iran-backed militant group is firmly entrenched at all levels of the Lebanese political system including the government (the ministerial cabinet, i.e. majlis al wozara), the various state institutions, and the parliament. Hezbollah’s growing local and regional influence can be attributed to the astuteness of its leadership, its military prowess, and its substantial financial resources, including a yearly budget allocated by Iran.

The Israeli army estimated in 2018 that Hezbollah received between USD 700 million - 1 billion per year from Tehran.([1]) Sources within Hezbollah who spoke to the author added that the group has been diversifying its revenue stream through both licit and illicit funding. In recent years, drug and money laundering scandals have been linked to Hezbollah in South America, the United States, Europe, and Africa. In Lebanon, media reports and interviews with Hezbollah members have pointed to the involvement of figures in and close to the organization in drug and money laundering scheme scandals and in the grey economy.

Locally, much ambiguity surrounds the debate around Hezbollah’s involvement in the drug trade for several reasons including but not only because of widespread support the organization enjoys within its community. First, according to interviews conducted by the author in Lebanon, Hezbollah is mostly known to have directly dealt in drugs schemes with members of the Israeli military in exchange for information, also called “drug-for-intelligence”.([2]) Second, with the exception of a few situations, Hezbollah has been indirectly linked to illicit activity, via its supporters and donors. Another reason for the ambiguity is that in South America, radical Islamists whether affiliated with the Palestinian Jihad, Iran, and Hezbollah are often bundled together without clear distinction. Finally, Hezbollah members directly involved with illicit activity in Lebanon often use the coverage provided by their status in the organization to operate as free business agents, which highlights Hezbollah’s growing internal corruption.([3])

Taking all of these nuances into consideration, this paper will examine Hezbollah’s various revenue streams. In a first section, the paper looks into Hezbollah’s sprawling structure and its relationship with Iran. The second section will look at Hezbollah’s international illicit activity. The final section will focus on the organization’s illicit activity in Lebanon and Syria. This paper relied primarily on interviews conducted by the author with current and former Hezbollah members as well as experts and individuals close to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

-

Hezbollah’s Structure and Financial Relationship with Iran

In the late 1970’s, when southern Lebanon was engulfed in a war against Israel, a Shiite group known as The Amal Movement rose to power. The group, founded by Sayed Musa Sadr, supported the Palestinian struggle against Israel. In 1982, the organization split after its new leader Nabih Berry – now incumbent speaker of the Lebanese Parliament – decided not to fight Israel’s advance into Lebanon. This decision was contested by the Amal party’s Islamic branch, which defected as a result. The latter faction was trained by Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corp (IRGC) forces, which had been sent to Lebanon to stop the progress of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).([4]) With the support of Iran, a politico-military command structure bringing Islamists and former Amal cadres together and an ideological platform known as the ‘Manifesto of the Nine’ were forged for the nascent resistance, marking the foundation of Hezbollah.([5]) The platform called for jihad against Israel, emphasized Islam as the movement’s doctrine, and declared the signatories’ adherence to the Iranian wilayat al-faqih ideology.

Iran realized that in order to protect its military gains in Lebanon, it had to capture the hearts and minds of its proxy’s popular base. With Iran’s assistance, Hezbollah built an extensive network of social services in Lebanon.([6]) According to a report by the Middle East Policy Council (MEPC), Hezbollah developed a highly organized system of health and social service organizations under the umbrella of its Social Unit, Education Unit, and Islamic Health Unit. According to the MEPC, Hezbollah’s Social Unit includes four organizations: the Jihad Construction Foundation (Jihad al-Binaa), the Martyrs’ Foundation, the Foundation for the Wounded, and the Khomeini Support Committee. In the early 2000’s, the Jihad Construction Foundation delivered water to about 45 percent of the residents of Beirut's southern suburbs and led reconstruction efforts in the southern suburbs after the 2006 war with Israel. In an interview with the author, Annahar columnist and Hezbollah expert Brahim Beyram estimated that Iran provided Hezbollah with $200-300 million a year. However in 2017, the IDF assessed that Hezbollah was receiving around $830 million per year from Iran,([7]) with the expansion of the Lebanese Hezbollah operations into Syria, where over 7,000 fighters were at the time intermittently deployed. A figure that is believed to have dropped significantly with winding down of the conflict.

A source close to Hezbollah’s fighters told the author that “besides being financed by Iran, Hezbollah has diversified its money stream and is trying to be more autonomous financially.” This could explain growing accusations against Hezbollah about its involvement in illicit activities. According to Dr. David Asher, a senior fellow at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (FDD),([8]) Hezbollah’s drugs-for-intelligence program has evolved into a massive drugs-for-profit initiative. “Hezbollah, partnered with Latin American cartels and paramilitary partners, is now one of the largest exporters of narcotics from South and Central America to West Africa into Europe and is perhaps the world’s largest money laundering organization,” said Asher in a 2017 congressional testimony in front of the House Foreign Affairs Committee.([9])

-

Hezbollah’s International Illicit Activities

Hezbollah relies on a sprawling global network of members engaged in various illicit activities. Much of this effort is focused in Latin America. Hezbollah’s illicit activity in South America appears to be focused on two main areas. Through supporters within its popular Shiite base in keys areas such as the tri-border area (TBA) of Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina, as well as in Colombia and Venezuela. “Hezbollah’s drug trafficking operations in Latin America are spread over a number of places. The TBA is one; Colombia is another; there also important centers of trade that are used for money laundering purposes and smuggling, such as free trade zones there,” said Dr. Emanuele Ottolenghi, a senior fellow at FDD, working on the Iran program.([10]) In addition, Hezbollah’s activities have also expanded to other countries and regions such as the U.S. and Europe.

- The Tri-Border Area

In 2004, Assad Barakat was described by the U.S. Department of the Treasury as “one of the most prominent and influential members” of Hezbollah, according to a paper by Matt Levitt, an expert on terrorism and security at the Washington Institute For Near East policies.([11]) Barakat’s import-export store at the Galeria Page shopping center in Paraguay was reportedly used for various nefarious activities ranging from counterfeit currency operations to drug running. Levitt’s paper described the 2006 arrest of Farouk Omairi by the Brazilian Federal Police in Operation ‘Camel,’ for providing travel support to cocaine smugglers. Omairi was believed to be acting as regional coordinator for Hezbollah and was involved in trafficking narcotics between South America, Europe, and the Middle East.

Paraguay has reportedly arrested Moussa Ali Hamdan in 2010 for providing material support to Hezbollah by selling counterfeit goods, money, and passports.([12]) In 2013, Wassim Fadel was arrested in Ciudad del Este, Paraguay after he had used a 21-year-old Paraguayan girl as a “drug mule” to smuggle narcotics to Europe. The girl was caught with 1.1 kilos of cocaine in her stomach. According to a statement by Paraguayan police published by MEE, Fadel reportedly transferred the money he made from both narco-trafficking and the pirating of CDs and DVDs into bank accounts owned by people connected to Hezbollah located in Turkey and Syria. In May 2018, Foreign Policy reported that Paraguayan authorities raided Unique SA, a currency exchange house in Ciudad del Este, Paraguaya, and arrested its owner Nader Farhat for his role in an alleged $1.3 million drug money laundering scheme.([13]) “Farhat is alleged to be a member of the Business Affairs Component, the branch of Hezbollah’s External Security Organization in charge of running overseas illicit finance and drug trafficking operations,” said the article.

2. Venezuela

In 2008, the U.S. Department of Treasury sanctioned Hezbollah supporter Ghazi Nasr al-Din, a former Chargé d' Affaires at the Venezuelan Embassy in Damascus.([14]) Hezbollah maintained a friendly and close relationship with the Venezuelan government led by Hugo Chavez, which evolved “into a tight ideological and business partnership,” according to an article published by Now Lebanon.([15]) The same article, quoting Lebanese Hezbollah expert Kassem Kassir, underlined that “a number of students and young men went [to Venezuela] to participate in festivals, conferences and workshops. There were some consultants of Chavez who came to Beirut and visited Hezbollah officials.”

According to U.S. authorities, Venezuela acts as a safe heaven and a source of funding for Hezbollah members and supporters. In 2015, ABC International reported that Nasr al-Din maintained a close relationship with Tarek Aissami,([16]) former vice president of Venezuela who was accused by the U.S. of facilitating drug shipments out of Venezuela and of drug trafficking, and together they attended a meeting with members of the Cartel of the Suns, a powerful network of Venezuela traffickers. In 2009, Nasr al-Din was also linked to the transportation of 400 kilos of cocaine from Venezuela to Lebanon via Damascus, transported by Conviasa, the Venezuelan flag carrier.

“Spanish investigative journalist, Antonio Salas who covered extensively the subject, has emphasized that a group of Hezbollah members linked to the Nasr al-Dingroup have engaged in drug trafficking under protection of Aissami. These people enjoyed a special (privileged) relation with the state,” underlined expert Douglas Farah, in an interview with the author.([17])

3. Colombia

In 2008, U.S. and Colombian investigators dismantled an international cocaine smuggling and money laundering ring that allegedly used part of its profits to finance Hezbollah.([18]) At the heart of the case was a kingpin in Bogota, Colombia, named Chekry Harb, who went by the alias "Taliban." According to the LA Times, Harb's group paid Hezbollah 12 percent of its profits, much of it in cash. “Harb brags about his uncle in the court documents being a senior member of Hezbollah,” said Ottolonghi to the author.

In December 2011, U.S. authorities accused Lebanese drug kingpin Aymen Jomaa, operating out of Medellin, Colombia, of allegedly helping to smuggle large amounts of cocaine into the U.S. and laundering more than $250 million for the Mexican drug cartel Los Zetas.([19]) Aymen Jomaa worked with at least nine other people and 19 entities to smuggle cocaine out of Colombia, then launder the drug-related proceeds from Mexico, Europe, West Africa, and Colombia through a Lebanese bank. Sometimes part of that money was sent to Mexico City in cash shipments to be delivered to Los Zetas. The U.S. investigation also linked a money-laundering scheme to Elissa and Ayash Exchange,([20]) and to the Lebanese Canadian Bank, which were sanctioned under the USA Patriot Act 311. “The link between Aymen Jomaa and Hezbollah was made because the money was directly traced back to Hezbollah controlled accounts although Jomaa was known mostly to be a supporter of the militant group,” said Farah. “Jomaa laundered on average 200 million dollars a month for drug cartels. Based on a number of other cases, we know that Hezbollah facilitators take 15-20 percent share a year. That means that the Jomaa operation alone would generate more than 400 million a year alone for this organization,” said Ottolonghi in an interview with the author.

Investigators believe that some of the drug profits money was laundered through a used car trade-based scheme from the United States to West Africa. According to a report by the U.S. Department of the treasury,([21]) figures close to Hezbollah were believed to be involved with a drug merchandise and money laundering operation where products were transported across the Togo and Ghana borders on their way from Benin to the airport in Accra, and the cash was then shipped by Middle East Airlines to Lebanon. Hezbollah affiliates deposit bulk cash into the financial exchange houses with the money then routed through the Lebanese Canadian Bank and other financial institutions and subsequently wire transferred to the United States so the used-car businesses can purchase vehicles. The vehicles were then shipped to West Africa for resale, said the report.

4. The Caribbean

In 2009, 17 people were reportedly arrested in Curacao for alleged involvement in a drug trafficking ring with connections to Hezbollah.([22]) The police underlined that some of the proceeds, funneled through informal Middle Eastern banks, went toward supporting groups linked to Hezbollah in Lebanon. "We have been able to establish that this group has relations with international criminal organizations that have connections with the Hezbollah," prosecutor Ludmila Vicento said to the Guardian. The amount confiscated by the police was significant and included two shipments of cocaine totaling 2,000 kilograms (4,400 pounds). The traffickers used cargo ships and speedboats to import the drugs from Colombia and Venezuela for shipment to Africa and beyond to Europe, according to Curacao authorities.

5. The United States

According to a report by Matthew Levitt, in 2009 the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency revealed a series of Hezbollah criminal schemes in the U.S., which ranged from stolen laptops, passports, and gaming consoles to selling stolen and counterfeit currency, procuring weapons, and a wide range of other types of material support.([23]) “In those cases, senior Hezbollah officials from both the organization's public and covert branches played hands-on roles in the planning and execution of many of the criminal schemes,” said Levitt. In July 2015, Lebanese National Ali Hassan Mansour, was arrested pursuant to a provisional arrest warrant issued in the Southern District of Florida by French authorities through diplomatic channels.([24]) Mansour, a money launderer based in Beirut, was charged with multiple counts of money laundering over the course of a narcotics conspiracy. The report labeled Mansour as being a key money launderer and drug trafficker for Hezbollah’s External Security Office, and Business Affairs Component (BAC) global illicit network.

In 2017, another Lebanese man accused of trying to use his ties to Hezbollah to further a scheme to launder drug money pleaded guilty in New York.([25]) Joseph Asmar worked with Lebanese businesswoman Iman Kobeissi, who had boasted she could use her Hezbollah connections to provide security for drug shipments. Kobeissi, who had been arrested earlier, had admitted she had friends in Hezbollah who wanted to purchase cocaine, weapons, and ammunition, according to the complaint.([26]) Kobeissi said her associates in Africa could provide security for planeloads of cocaine heading to the U.S. and other countries. She was also accused by prosecutors of having laundered hundreds of thousands of dollars in illegal drug money through transactions in European and Lebanese banks. “The Iman Kobeissi case is one of the cases that have directly linked senior Hezbollah leadership to drug trafficking activities,” said Ottolenghi

6. Europe

In January 2016, ‘Operation Cedar’ raids targeted Hezbollah operations in France, Germany, Italy, and Belgium, led by local law enforcement and supported by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.([27]) These raids resulted in the arrest of over a dozen individuals involved in international criminal activities such as drug trafficking and drug proceed money laundering. During the raids, several millions in assets and cash were seized that were believed to be linked to drug proceeds that were collected by money launderers throughout Europe. ”These actions specifically targeted Lebanese Hezbollah criminal operations in Europe,” said Asher at the time.([28]) For Ottolenghi, Operation Cedar is another case that directly tied Hezbollah leadership to illegal activities.([29]) “Europe is a booming market for cocaine. Hezbollah taps that market by facilitating multi-ton shipments of cocaine from Latin America into Europe. Hezbollah operatives are involved in laundering its revenues there on behalf of local criminal syndicates,” he noted.

These prominent cases linked to Hezbollah’s illicit activity, and others not described here, demonstrate that networks linked to the Lebanese militant group were clearly operating at an international level. Project Cassandra, which was unveiled last year in 2017 by Politico magazine,([30]) was launched in 2008 by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to target Hezbollah’s illicit funding streams. The project showed that cocaine shipments – some traveling from Latin America to West Africa and on to Europe and the Middle East, and others through Venezuela and Mexico to the U.S. – were all connected to a line of dirty money, laundered through used car schemes that were shipped to Africa. The FBI believed at the time that the Hezbollah network was collecting $1 billion a year from drug and weapons trafficking, money laundering, and other criminal activities.

-

Hezbollah’s Legalized Financing

Hezbollah does not rely on illicit trade alone for financing, as the organization also has revenue from legitimate businesses in Lebanon and Africa. “Part of Hezbollah’s attempt to diversify its revenue stream is the organization’s licit enterprises. Hezbollah uses front figures to operate legitimate businesses mostly involved in construction, car dealing as well as gas stations in Lebanon, and trading activities in Africa,” said a source close to the party to the author.

In recent years, Hezbollah-linked businesses have been targeted by U.S. law enforcement organizations for money laundering activity. In 2018, the U.S. Treasury designated six individuals and seven entities pursuant to Executive Order (E.O.) 13224,([31]) which targets terrorists and those providing support to terrorists or acts of terrorism. Specifically, they designated Lebanon-based Jihad Muhammad Qansu, Ali Muhammad Qansu, Issam Ahmad Saad, and Nabil Mahmoud Assaf, and Iraq-based Abdul Latif Saad and Muhammad Badr-Al-Din for acting for or on behalf of Hezbollah member and financier Adham Tabaja or his company, Al-Inmaa Engineering and Contracting. The U.S. also designated Sierra Leone-based Blue Lagoon Group LTD and Kanso Fishing Agency Limited, Ghana-based Star Trade Ghana Limited, Liberia-based Dolphin Trading Company Limited (DTC), Sky Trade Company, and Golden Fish Liberia LTD, and Lebanon-based Golden Fish S.A.L. (Offshore) for being owned or controlled by Ali Muhammad Qansu. Adham Tabaja had already been previously sanctioned in 2015, along with Kassem Hijaj and Husein Ali Faoud.([32]) “The DEA has identified Adham Tabaja as one Hezbollah‘s most senior member within the organization’s Business Component Affairs,” said Ottolenghi. Tabaja is also known to be a majority owner of the Lebanon-based real estate development and construction firm Al-Inmaa Group for Tourism Works. The company’s subsidiaries include Al-Inmaa Engineering and Contracting, which operates in Lebanon and Iraq, as well as Lebanon-based Al-Inmaa for Entertainment and Leisure Projects. In 2018, Tabaja is believed to have used the Iraqi branches of Al-Inmaa Engineering and Contracting to obtain oil and construction development contracts in Iraq. Kassem Hijaj was also accused of investing in infrastructure that Hezbollah uses in both Lebanon and Iraq.

Another man, Husayn Ali Faour, was accused of being a member of Hezbollah’s Islamic Jihad, which is believed to be the unit responsible for carrying out the group’s overseas terrorist activities.([33]) Faour managed the Lebanon-based Car Care Center, a front company used to supply Hezbollah’s vehicle needs. Faour worked with Tabaja to secure and manage construction, oil, and other projects in Iraq for Al-Inmaa Engineering and Contracting. A new wave of sanctions in 2019, targeted Hassan Tabaja, the brother of Adham and Wael Bazzi for facilitating Hezbollah financial operations.([34])

A source close to Hezbollah members told the author that in addition to car, trading, and construction activity, the organization is also involved in the diamond and gold trade in Africa. The expert Douglas Farah concurs, adding that Africa was a good collection point for Hezbollah, whose activity ranges from blood diamond trade to Europe, especially to Antwerp, in Belgium.

Diamond and trade are not the only business Hezbollah members are involved in. In 2012, Reuters reported that the Democratic Republic of Congo had awarded forestry concessions to the Trans-M company, which was subject to sanctions by the U.S. for being a front company used by Hezbollah.([35]) Reuters explained that the concessions covered a 25-year lease for hundreds of thousands of hectares of rainforest in the central African country. “The concessions are capable of generating hundreds of millions of dollars in revenues over 25 years, if fully exploited,” forestry experts told Reuters. Trans-M was controlled by businessman Ahmed Tajideen, known to also be the owner of Congo Futur, a company that manages sawmills and is accused by the U.S. government of being a front for Hezbollah.

-

The Debate Around Hezbollah’s Criminal Enterprises and its Illicit Lebanese and Syrian Activities

Allegations of Hezbollah’s illicit activity schemes have been denounced by many Hezbollah members as well as by Lebanese experts privy to the organization’s internal workings. “Members of Hezbollah are known to be honorable and dedicated to the cause, this has made the success of the organization since its inception,” said Ahmad, a Hezbollah fighter who spoke to the author on the condition of anonymity. Despite the amount of attention they received in the press, several cases, such as that of Chekry Harb, are in many ways circumstantial. Harb was accused of cooperating with Hezbollah and having family relations with some of its members. A nephew of a Hezbollah operative, Harb donated large amounts to the organization. In the cases of Hamdan and Fadel there was little hard evidence of a clear link with Hezbollah. “While some people arrested in South America were directly linked to Hezbollah, many individuals involved in illicit activities are actually either sympathetic to Hezbollah or were intimidated by them into giving them donations,” said Farah. In addition, Farah underlines that in South America, no distinction is made between Iranian and Hezbollah operators, which adds to the general confusion.

Nonetheless, other cases such as Kobeissi, Farhat, Barakat, and Omairi, show a clear and direct connection between Hezbollah members and criminal entrepreneurs. In the above mentioned cases, even when the organization was not directly responsible for the illicit trade, it facilitated it and covered it. In addition, Hezbollah knowingly received money from shady business figures or drug dealers sympathetic to its cause.

For Annahar’s columnist and Hezbollah expert, Ibrahim Bayram, the U.S. accusations against Hezbollah and its supposed involvement in the drug trade are farfetched and political in nature. “There is a clear American agenda against Hezbollah and these drug trade allegations are there to support it,” said Bayram.([36])

However, at the local level in Lebanon, Hezbollah members appear to be directly involved in criminal enterprises including drug dealing, racketeering, production of counterfeited money and medication, both with or without the knowledge of the top leadership. “Hezbollah’s direct dealing with drugs is solely for political and security reasons. Most drug deals are connected to the drug-for-intelligence and information scheme it has run with members of the Israeli army,” said Hassan, a Hezbollah fighter who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Since its creation, Hezbollah has been using drug dealers, to pursue the organization’s intelligence and military objectives.([37]) Hezbollah was known to employ drug dealers for advancing its political interests, taking advantage of its control over Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, which is known for its lucrative poppy and hashish production to infiltrate the Israeli military. The organization gave drug dealers political protection as long as they provided the organization with information on Israel. Over the years, a number of Israeli military officers have been charged with drug smuggling or dealing from Lebanon and providing information to Hezbollah.([38]) Hezbollah has also relied on drug dealers to recruit agents among Israeli Arabs.

According to Hezbollah fighters interviewed by the author, Hezbollah’s involvement in the drug trade in Lebanon is no longer driven solely by political or military interests. Sources explain that today, some Hezbollah commanders are tapping into the lucrative drug market for their own personal benefit. This has happened as the organization’s clout has grown in recent years, with its consolidation of power in Lebanon in 2006, and its entry into the Syrian war in 2011. The author could not confirm or invalidate these allegations.

“Hezbollah turns a blind eye to the drug plantations around its training camps, and drug dealers provides it with significant contributions from their proceeds,” said a source close to the organization’s members, on the condition of anonymity. The Lebanese army has long been instructed not to approach spots where Hezbollah is known to host its training camps in the Bekaa, which is the hub of Lebanon’s drug production. One Hezbollah commander hailing from the Bekaa told the author that some members of the organization were involved in abetting dealers involved in the transfer of cocaine into Lebanon to be smuggled into Syria, an accusation the author could not confirm independently. According to a source involved in the drug trade, cocaine is smuggled into Lebanon where it is processed and sent to Syria, and from there to the Gulf.

Machines used in the production of the drug captagon are smuggled into Lebanon illegally via the port of Beirut where Hezbollah is influential. “Hezbollah commanders also facilitate through their control of Lebanese borders with Syria their export of drugs such as captagon,” added the Bekaa commander interviewed by the author and asked to remain anonymous. Lebanon is a large exporter of captagon, sent through the Beirut port or across the Syrian border, with the goal of reaching Gulf countries, explained a source close to the drug dealing networks on the condition of anonymity.

Hezbollah fighters, who spoke to the author for this report, accused the organization’s commanders of covering up illicit business dealings. “Hezbollah’s leadership is often aware of the dealings but has seem reluctant to reign on them because of the high military or political status many commanders have acquired within the organization, especially after the war against Israel in 2006 and currently in Syria,” complained one fighter. It is important to understand why Hezbollah is not doing anything about its members’ illicit activity and rampant corruption, because of its reliance on these commanders for its external operations.

In addition to the drug trade, members of Hezbollah are also involved in the production of counterfeited money in the Lebanese suburb of Dahieh, explained the Bekaa Hezbollah commander in an interview by the author. The counterfeit bills are in turn traded via an international network, which is why Lebanon is known to be a producer of counterfeited money. In 2016, the New York Post reported that a large money-counterfeiting ring was busted when a Lebanese man was arrested for allegedly selling hundreds of thousands of dollars in counterfeit U.S. currency to a global network of clients in Iran, Malaysia, and elsewhere.([39]) According to the Post, between 2012 and 2014, Louay Ibrahim Hussein and other members of the ring sold more than $620,000 in high-quality fake $100 bills and €150,000 in fake Euros to undercover agents. Hussein had allegedly claimed to undercover agents that he had access to as much as $800 million in high-quality counterfeit currency.

Other illicit dealings by Hezbollah members are connected to Iranian aid to Lebanon. One fighter also speaking on condition of anonymity explained that since 2006, food aid given by Iran to Hezbollah, often ended up being sold on the Lebanese market instead of being distributed free. In 2013, a warrant was issued against the brother of the Lebanese Minister of State for Administrative Reform, Mohammad Fneish Abdul Latif Fneish, in connection to a case of illegally imported medications.([40]) “The brother of another Hezbollah minister has also been accused of running a Captagon production facility in Dahieh, every one of us is aware of the issue,” said the Hezbollah commander hailing from the Bekaa and who spoke on condition of anonymity. The author could not independently confirm the accusations.

The Syria war has been another financial boon for Hezbollah commanders, said a Hezbollah fighter speaking on condition of anonymity to the author. “A lot of the weapons seized from Syrian ‘terrorists’ or from ISIS is not given to the Syrian army but sold on the black market ( in Lebanon), which has contributed for the decline of weapons prices such as Kalashnikov, PKC and B7 on the Lebanese market,” said a source close to Hezbollah fighters. The Syrian war has flooded the region with weapons being smuggled into the country. In 2016, a team of reporters from the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) and the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) uncovered discreet sale of more than €1 billion worth of weapons in the past four years to Middle Eastern countries that were known to ship arms to Syria.([41]) Thousands of assault rifles such as AK-47s, mortar shells, rocket launchers, anti-tank weapons, and heavy machine guns were being routed through an arms pipeline from the Balkans to the Arabian Peninsula and countries bordering Syria.

“There might have one or two accusations of corruption with the war in Syria but these are exceptional and individual cases linked to the conflict there. Hezbollah has very strict rules about anything seized in war theaters and even during battle we were forced to do a detailed inventory of what we seized, and we are obliged to report any mismanagement,” said one Hezbollah commander, commenting on Hezbollah’s alleged illicit activity.

Sources close to Hezbollah admit that its members have been promised lucrative infrastructure contracts in Syria, specifically in Homs and Aleppo. Sometimes, Hezbollah members sponsor Lebanese businessmen getting these contracts in return for a cut of the profits. “The same scenario is taking place in areas under Hezbollah control such as Dahieh. Hezbollah commanders are involved in the parallel economy of providing electricity, satellite connection and water, leaving the government with failing services,” said the source close to the fighters.

Conclusion

Despite the circumstantial nature of the evidence in some cases, Hezbollah’s involvement in large international criminal enterprises is difficult to dismiss. Reports and investigations all point to Hezbollah’s direct or indirect involvement in illicit activity at the international level. At the local level, the organization’s growing clout and the rampant climate of corruption prevailing in Lebanon have been conducive to the increasing involvement of Hezbollah-linked figures in illicit activity.

Although Western accusation of Hezbollah’s corruption and involvement in criminal activity do not appear to have much influence over the organization’s popular base of support, stronger sanctions are taking a toll, forcing the organization to try to make cuts in it budget or attempt to outsource some services to Lebanese government ministries. There are anecdotal reports of members of Hezbollah’s popular base complaining of cuts in aid to the families of martyrs and challenges faced by Hezbollah members in accessing the organization’s health services. With de-escalation agreement in effect in Syria, Hezbollah has been able to bring back a large number of its fighters, thus limiting its military expenditures. The organization’s members have also been slapped by a number of U.S. sanctions. “This nonetheless does not affect Hezbollah which does not resort to the official financial system,” said Bayram. However, sanctions have impacted Hezbollah’s capability to launder its money via front individuals and companies. A U.S. based financial consultant working on countering money laundering activities told the author that U.S. correspondent banks are forcing Lebanese banks to closely monitor and close accounts suspected of laundering money for Hezbollah, with dozens of accounts terminated as a result. A high-level source in a Lebanese public financial institution explained that the Lebanese Central Bank has applied strict measures to prevent Hezbollah’s use of the banking sector. “The use of Hezbollah in construction, car rental, luxury store as fronts is nonetheless a possibility,” says the official.

Besides the challenge posed by increased sanctions, Hezbollah is faced with a growing conundrum linked to corruption. The organization’s promise to focus on fighting corruption in the Bekaa Valley during the electoral campaign prior to the May parliamentary elections is an indirect admission of the poor state of affairs when it comes to governance issues and deep dissatisfaction of its popular base. Corruption among Hezbollah members is not the only grievance of Shiites, whose complaints focus more on Lebanon’s general state of affairs. Hezbollah previously claimed that it focused only on its resistance activities and Lebanon’s military defense, but with its participation in successive national governments since 2008, this argument no longer holds. Furthermore, deteriorating economic conditions are challenging Hezbollah, with sources within Hezbollah reporting a growing dissatisfaction due to severe pay cuts. It seems that financial sanctions, led to a decline in the organization’s revenues, coupled with increased corruption scandals and an extended truce period with Hezbollah’s nemesis Israel, could prove more detrimental to the group on the longer run.

([1])Top general sees increased Iran spending on foreign wars, Dan Williams, Reuters, January second 2018:

https://reut.rs/2XMMm63

([2]) Israel soldier among arrested 'Hezbollah spies, , BBC, 20 June 2010 , https://www.bbc.com/news/10462662

([3]) Interview with Hezbollah commander, by author, Dahieg, February 2018,

([4])Nicholas Blanford, Warriors of God: Hezbollah’s Thirty Year Struggle against Israel (2011).

([5]) Marc Devore, Exploring the Iran-Hezbollah Relationship: A Case Study of How State Sponsorship Affects Terrorist Group Decision-Making, Perspective on terrorism, Vol 6, No 4-5 (2012), http://www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/218/html

([6]) Shawn Teresa Flanigan, Mounah Abdel-Samad, Hezbollah's Social Jihad: Nonprofits as Resistance Organizations, volume 16 Middle East Policy Council.

([7]) Ahronheim Anna, Iran pays $830 million to Hezbollah, September 15 2017, Jerusalem Post , https://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Iran-News/Iran-pays-830-million-to-Hezbollah-505166

([8]) https://www.cnas.org/people/david-asher

([9]) Asher David, Attacking Hezbollah, financial networks , June 8 2017, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA00/20170608/106094/HHRG-115-FA00-Wstate-AsherD-20170608.PDF

([10]) Interview with Emanuel Ottolonghi by the author, June 2018.

([11]) Levitt Matt, Hezbollah narco-terrorism, September 2012, IHS Defense, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Levitt20120900_1.pdf and https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/js1720.aspx

([12]) Spetjens Peter, Paraguay: Is Israel's latest 'best friend' also a Hezbollah haven?, may 21 2018, Middle East Eye (MEE)

([13])Ottolonghi Emanuele, Lebanon is protecting Hezbollah’s cocaine trade in Latin America, June 15 2018, Foreign policy, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/06/15/lebanon-is-protecting-hezbollahs-cocaine-and-cash-trade-in-latin-america/

([14])Treasury Targets Hezbollah in Venezuela, June 2008, US Department of treasury, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/hp1036.aspx

([15]) https://now.mmedia.me/lb/en/reportsfeatures/how_much_does_venezuela_matter_to_hezbollah

([16])Blasco Emily, El FBI investiga la conexión entre el narcoestado venezolano y Hizbolá, January 31 2015, ABC, https://www.abc.es/internacional/20150130/abci-venezuela-droga-201501302321.html

([17]) Douglas Farah is a national security consultant and analyst, the president of IBI Consultants, and a Senior Fellow at the International Assessment and Strategy Center.

([18])Chris Kraul and Sebastian Rotella, Drug probe finds Hezbollah link, october 22 2008, LA ztimes, http://articles.latimes.com/2008/oct/22/world/fg-cocainering22

([19]) Longmire Sylvia, DEA Arrests Hezbollah Members For Allegedly Laundering Cartel Money, February 5 2016, Homeland Security https://inhomelandsecurity.com/dea-arrests-hezbollah-members-allegedly-laundering-cartel-money/ and https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/pages/tg1035.aspx

([20]) “Attacking Hezbollah’s financial network: policy options” June 8, 2017 statement of Derek S. Maltz, United States House of Representatives House Committee on Foreign Affairs.

([21]) Finding that the Lebanese Canadian Bank SAL is a Financial Institution of Primary Money Laundering Concern, Department of the Treasury, https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/LCBNoticeofFinding.pdf

([22]) https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/apr/29/curacao-caribbean-drug-ring-hezbollah

([23]) Levitt, Matt, Hezbollah's Criminal Networks: Useful Idiots, Henchmen, and Organized Criminal Facilitators, October 2016, National Defense University https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/hezbollahs-criminal-networks-useful-idiots-henchmen-and-organized-criminal

([24]) Asher Danid, Tracking Hezbollah’s Financial Network, June 8 2017, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA00/20170608/106094/HHRG-115-FA00-Wstate-AsherD-20170608.PDF

([25])Stemple Jonathan, U.S. says Hezbollah associate pleads guilty to money laundering conspiracy, June 27, 2017, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/usa-crime-hezbollah-asmar/u-s-says-hezbollah-associate-pleads-guilty-to-money-laundering-conspiracy-idUSL1N1IS1K2

([26]) Ya libnan, 2 Lebanese charged with laundering money for Hezbollah, October 10, 2015 http://yalibnan.com/2015/10/10/2-lebanese-charged-with-laundering-money-for-hezbollah/

([27]) Asher David, Tracking Hezbollah’s Financial Network, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA00/20170608/106094/HHRG-115-FA00-Wstate-AsherD-20170608.PDF

([28]) Asher David, Tracking Hezbollah’s Financial Network, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA00/20170608/106094/HHRG-115-FA00-Wstate-AsherD-20170608.PDF

([29]) Interview with Emaniel Ottolonghi, by the author June 2018

([30]) The secret backstory of how Obama let Hezbollah off the hook, December 2017, Politico, https://www.politico.com/interactives/2017/obama-hezbollah-drug-trafficking-investigation/

([31]) https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0278

([32]) Wilson Center, US sanctions target Businesses close to Hezbolllah, June 10, 2015 https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/us-sanctions-target-businesses-linked-to-hezbollah

([33]) Treasury Sanctions Hezbollah Front Companies and Facilitators in Lebanon And Iraq, Treasury Department, October 2015

([34]) US issues new Hezbollah-related sanctions, April 24 2019, Al-Jazeera, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/04/issues-hezbollah-related-sanctions-190424175927380.html

([35])Mahatani Dino, Exclusive: Congo under scrutiny over Hezbollah business links, March 16 2012, Reuters https://www.reuters.com/article/us-congo-democratic-hezbollah/exclusive-congo-under-scrutiny-over-hezbollah-business-links-idUSBRE82F0TT20120316

([36]) Interview with Brahim, Beyram, Beirut, March 2018.

([37]) Melman, Yossi, Hezbollah’s drug trail, October 72016, the Jersualem Post https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Analysis-Hezbollahs-drug-trail-469616

([38]) Israel soldier among arrested 'Hezbollah spies, June 2010, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/10462662

([39]) Eustaseuwich Lia, Lebanon man accused of selling counterfeited money abroad, July 26, 2016, New York Post, https://nypost.com/2016/07/26/lebanese-man-accused-of-selling-counterfeit-us-currency-abroad/

([40]) http://www.naharnet.com/stories/en/72039

([41]) https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/27/weapons-flowing-eastern-europe-middle-east-revealed-arms-trade-syria

ISIS and the Strategic Vacuum- The Dilemma of Role Distribution- The Raqqa Model

Executive Summary

- The Raqqa operation closely mirrors the Mosul operation both politically and militarily. Politically, it was launched amid disagreements and a lack of clarity about which local and international forces would participate and who would govern the city post liberation. Militarily, ISIS used the same strategy it used in Mosul aiming to exhaust the attacking forces with the use of improvised explosive devices instead of direct combat. ISIS also retreated from positions near the borders of Raqqa and took more fortified positions inside neighborhoods with narrow streets in an attempt to change the battle into an urban combat nature.

- The battle uncovered critical weaknesses in the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and its ability to fight alone. The SDF required heavy cover fire from Coalition forces as well as direct involvement of American and French forces, which deployed paratroopers in the area and changed the course of the battle by taking control of the Euphrates Dam and Tabqa Military Airport.

- The tense political environment and the various interests of regional and international players will significantly impact the battle for Raqqa and future battles against ISIS in Syria.

- This paper projects four scenarios about how the Raqqa operation and future operations could play out.

- First, the United States’ continued dependence on YPG-dominated SDF forces as its sole partner, which will exacerbate tensions with Turkey.

- Second, a new agreement or arrangement between Turkey and the U.S.

- Third, a new arrangement between Russia and the U.S. in Raqqa, similar to what took place in Manbij.([1])

- Fourth, the latest Astana agreement, which could set the groundwork for the U.S. to open the way for all Astana parties to participate in the Raqqa battle.

- The most important contribution of the U.S. in Syria was undermining the “post-Aleppo status quo”([2]) established by Russia in an attempt to create an environment more consistent with an American policy that is more involved in the Middle East, especially in Syria.

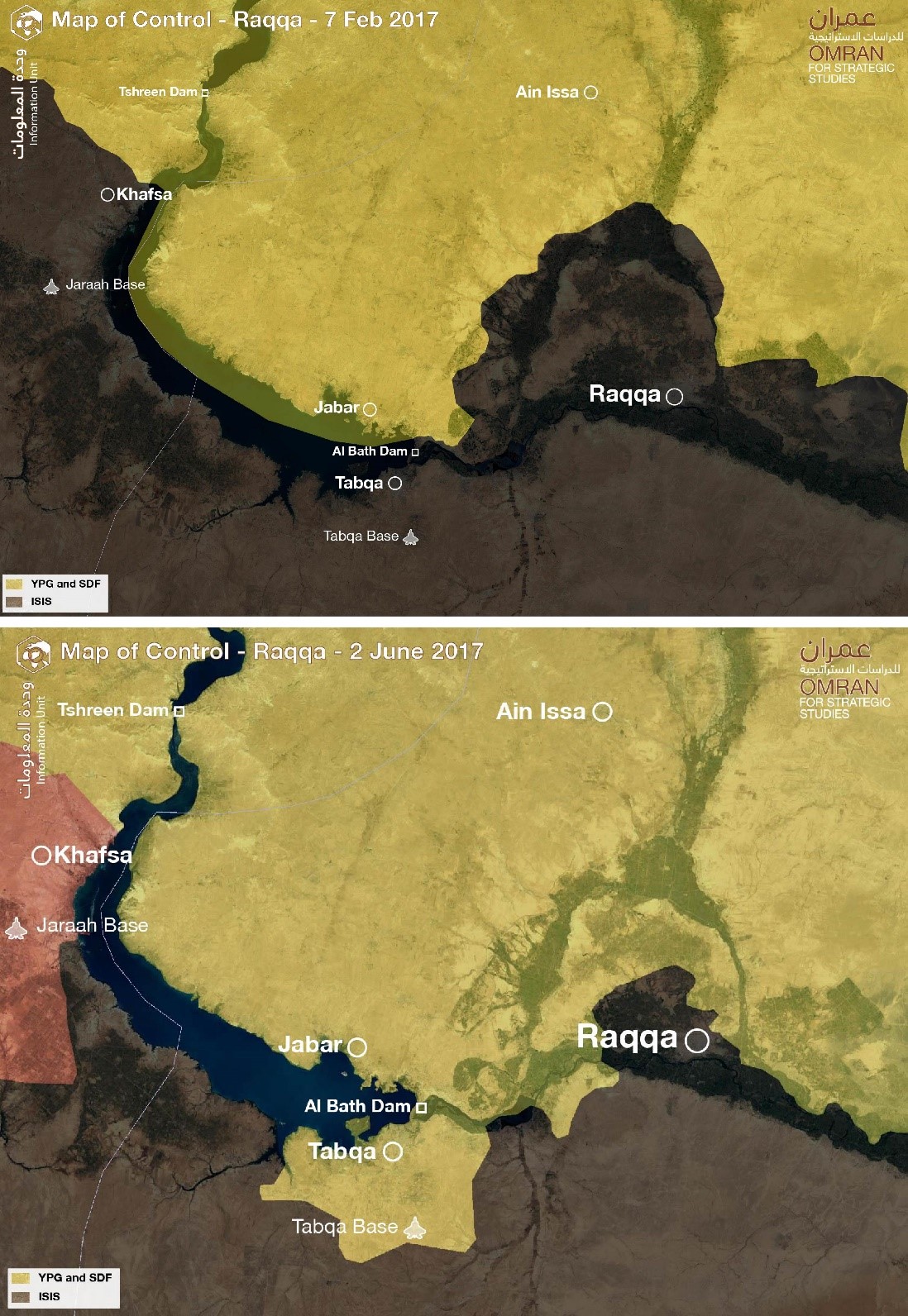

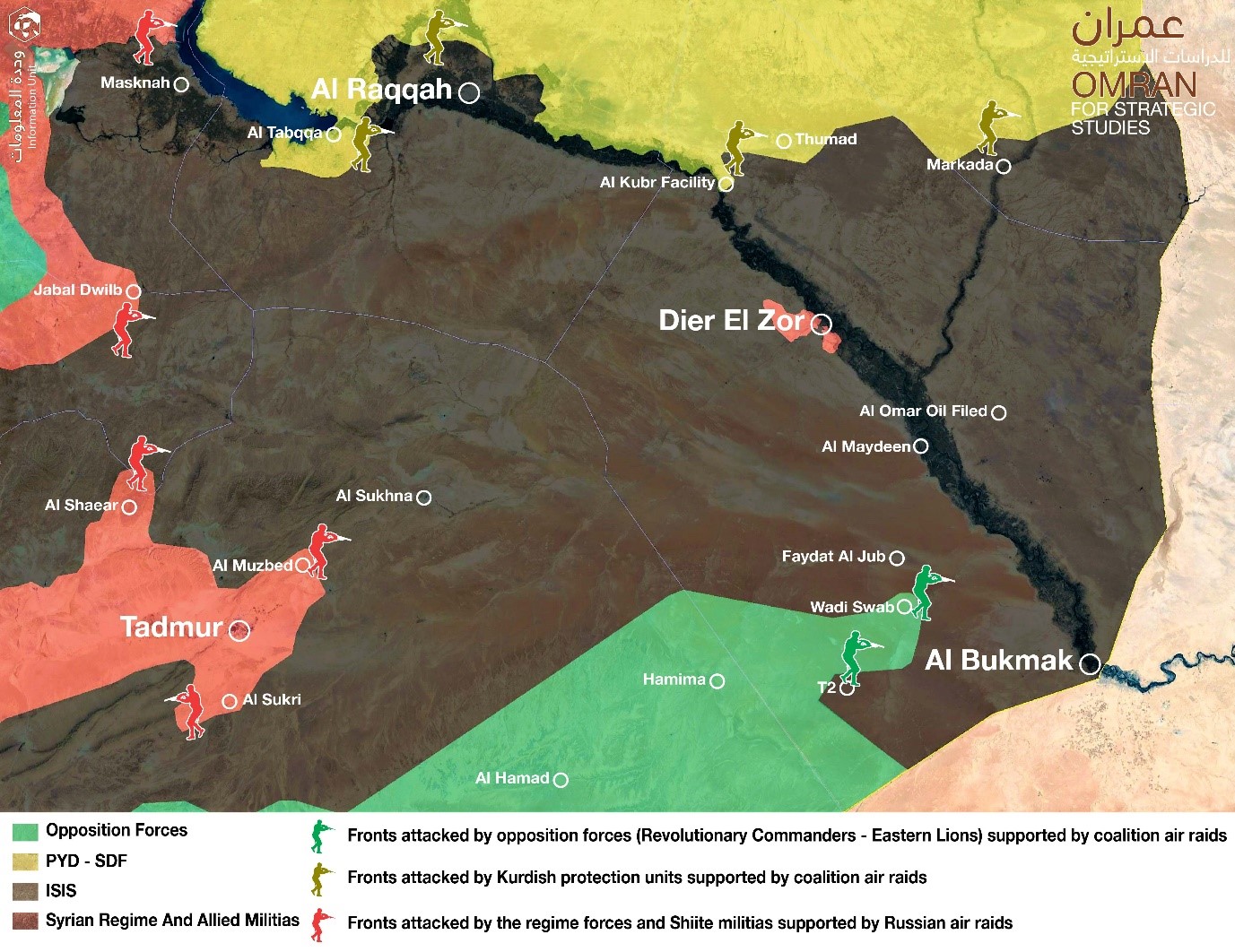

Introduction