Monthly Briefing on the Events of the Syrian Scene - July 2024

General Summary

This report provides an overview of the key political, security, and economic events in Syria during the month of July 2024, examining developments across various levels.

- Politically, the normalization process with the Assad regime advanced with Italy appointing an ambassador to Damascus. Additionally, seven countries submitted a "non-paper" to the European Union, urging it to abandon the Three No’s policy. The regime also expressed its readiness to establish a new relationship with Turkey.

- Security, instability continues to rise across Syria. In the northwest, protests escalated into violence and direct confrontations with Turkish forces, while the region witnessed the largest drone attack by regime forces against civilian targets in rural Aleppo and Idlib in 2024. In eastern Syria, the international coalition is strengthening its positions as Iran-backed militias increase their attacks.

- Economically, exports through the Nasib border crossing continued to decline, and the regime's economic policies have led to increased capital flight and a higher cost of living. The Autonomous Administration in northeastern Syria (AANES) implemented economic policies that negatively impacted the agricultural sector.

Impact of Regional and International Normalization on Local Actors

Amid the ongoing normalization and restoration of relations with Bashar al-Assad, Italy announced the return of its diplomatic mission and the appointment of an ambassador in Damascus. This move coincided with efforts by Italy and six other EU member states to abandon the Three No’s policy that shapes the EU's stance on the Syrian issue. Meanwhile, the Syrian Regime’s Foreign Ministry issued a statement welcoming Turkey's calls to restore relations with Damascus, expressing readiness to establish a new relationship with Turkey based on clear principles, including the withdrawal of illegally stationed forces from Syrian territory and the combating of "terrorist groups" that threaten the security of both countries and linking the normalization of relations between the two countries to a return to the pre-2011 status quo.

The statement shows the regime's willingness to begin the normalization process and respond to Turkey's calls, dropping the precondition of Turkish troop withdrawal before the Erdogan-Assad meeting.

The regional and international normalization process with the Assad regime is progressing steadily, despite the differing motivations of the involved countries. These motivations are primarily security-driven or involve experimenting with alternative solutions under the guise of offering incentives to the regime, based on a step-by-step approach to gradually change its behavior. However, the normalization process is unfolding in a way that favors the regime and serves its interests. Bilateral agreements provide the regime with more maneuvering space, as they are tailored to each country's individual interests. Additionally, these agreements help the regime evade political obligations and the implementation of international resolutions, particularly Resolution 2245.

Domestically, the Assad regime held legislative elections for the fourth term since the adoption of the new constitution in 2012, following years of stagnation in the Syrian scene since the cessation of military operations under the de-escalation agreements. These elections come shortly after the Baath Party elections, which showed Assad's efforts to re-engineer power centers within the party and strengthen his absolute control to make it a disciplined political force aligned with Assad's direction and capable of interaction and leadership in any new political landscape. The regime's insistence on holding the elections aims to project an image of resilience and victory despite the conspiracies and international pressures, while also evading political solutions by claiming to strengthen its popular legitimacy through elections. Western countries considered the environment unsuitable for elections, while official opposition bodies called for genuine democratic elections in accordance with international resolutions, representing all segments of the Syrian people, unlike the current parliament. Additionally, popular and media campaigns opposed these superficial elections.

In northeastern Syria, the atmosphere of rapprochement between Turkey and the Assad regime has raised concerns among the AANES, considering it an existential threat and describing the process as a large conspiracy against the Syrian people. The administration realizes that Turkey's policy shift is strategic, not tactical, and that this rapprochement will reduce its available options and present it with difficult challenges, especially as it – if successful – would close the door to any future agreement between the administration and the regime. This explains the statement by Mazloum Abdi, the General Commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), who affirmed that the Syrian crisis cannot be solved through violence and war, emphasizing the administration's readiness to engage in dialogue with all parties, including Turkey, to end the conflict and reach a political solution in Syria. To ease local tensions, the administration issued a general amnesty law in response to demands from the public, tribal leaders, and dignitaries. The amnesty includes hundreds of prisoners who committed crimes of terrorism and other offenses before the law was issued.

Rising Security Tensions: Popular Protests Increase Instability Indicators

In northwestern Syria, protests involved acts of vandalism against public and private property, including the burning of trucks, the removal of Turkish flags, and direct clashes with Turkish forces at several locations. This followed the acts of vandalism and attacks on Syrian refugees that occurred in Kayseri Province, Turkey, and in opposition to renewed talk of political normalization between Turkey and the Assad regime after Turkish officials' statements on rapprochement, which triggered the protests. Additionally, other factors led residents of these areas to express high levels of anger and frustration due to ongoing neglect of good governance issues, widespread corruption, security instability, and imbalanced civil-security relations, along with the lack of clear boundaries for the nature of relations with Turkey. Meanwhile, the Idlib region saw an escalation in military operations between regime forces and Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), with the regime launching the largest drone attack of 2024 on civilian sites in rural Aleppo and Idlib. HTS continued to carry out infiltration operations against regime forces, the most notable being operations along the Saraqib axis at the beginning of July.

In other areas, the reconciliation model remains characterized by security fragility across different regions. In the town of Kanaker, after the regime imposed a new security reconciliation aimed at enlisting draft dodgers into the army, opponents of the reconciliation attacked a regime headquarters. This reconciliation and the accompanying events come weeks after clashes between regime forces and local militants at the start of the previous month. In Suwayda, the leader of the Mountain Brigade, Marheg al-Jurmani, known for his support of the popular movement in the province and his responsibility for protecting demonstrations there, was assassinated. This assassination is the most significant incident in the province since the start of the popular movement, occurring shortly after the regime brought in security reinforcements to the province. In Daraa, clashes continued between two local groups in the city of Jasim in rural Daraa for over ten days following the assassination of a leader from one of the groups and accusations that the other was behind the attack. In the same province, fighters launched multiple attacks targeting various regime sites in the province, coinciding with roadblocks using burning tires, in response to the kidnapping of a family from the Al-Sanamayn area by a gang affiliated with the 4th Division in rural Homs. The attacks ceased after the family was released.

Meanwhile, 60 people, most of them civilians, were killed in areas controlled by the AANES due to security disturbances, killings, and tribal conflicts, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. Additionally, ISIS operations continued in areas under the AANES influence, with 21 different security incidents involving shootings, killings with sharp objects, and planting explosive devices and landmines, resulting in six deaths. Meanwhile, the American base in the Koniko gas plant in rural Deir Ezzor was hit by rockets fired by Iranian backed-militias. American planes responded by targeting the surroundings of the seven villages in areas under the control of pro-Iranian militias in rural Deir Ezzor with heavy machine guns. New military reinforcements arrived for coalition forces in the area, including a short-range air defense system called Avenger. The international coalition has also begun constructing observation towers along the Euphrates River in eastern rural Deir Ezzor to monitor the area and control the security situation amid an increase in tribal attacks from the opposite bank on SDF positions and concerns of an Iranian escalation against the U.S. presence in the region.

Syrian Economy in a Vortex of Crises: Declining Exports and Increasing Living Costs

Syrian exports of vegetables and fruits to Jordan through the Nasib border crossing continued to decline significantly during July 2024 due to Jordan's restrictions on truck entry, following repeated incidents where the regime used trucks to smuggle drugs. This forced Jordan to upgrade the border infrastructure, modernize its equipment, and impose strict conditions on trucks coming from Syria. These measures result in significant losses for Syrian farmers and traders due to the spoilage of goods during the long wait at the border. These actions also negatively affect Syrian exports abroad, impacting foreign currency earnings and potentially straining relations with Jordan if drug smuggling into its territory and through it to the Gulf countries continues.

Regarding the ongoing economic stagnation in Syria and the regime's continued inability to develop the investment environment, figures indicate a 44% decrease in the number of registered companies in Syria during the first quarter of this year compared to the same period last year, along with continued capital flight due to worsening economic challenges. The number of registered traders in the Damascus Chamber of Commerce also dropped from 9,890 to 8,200 traders within one year, down from 17,000 traders before mandatory registration in social security. This decline is attributed to the rising costs of business, particularly energy costs and imposed taxes, difficulties in securing essential business supplies due to their high prices, declining competitiveness of Syrian products, and the lack of incentives and facilities offered by the government. These factors have driven many businesses to relocate to other countries.

Regarding the cost of living in regime-controlled areas, the cost of living for a family of five exceeded 13 million SYP in early July, according to the Qasioun Newspaper Index, while the minimum cost of living reached about 8.1 million SYP. Meanwhile, the minimum monthly wage was only about 278,000 SYP, which covers just 2.2% of the average cost of living in the first three months of 2024 and 2.1% in the following three months. This gap between low wages and high living costs exacerbates poverty and increases the number of people in need, further weakening the purchasing power of citizens, deepening the economic recession, and potentially leading to psychological effects on Syrian families, increasing social tensions, and worsening the humanitarian crisis.In the context of shortages of essential services such as gas and electricity, the waiting time for receiving a gas cylinder reached 85 days in Damascus and 100 days in Homs. This has led to a rise in prices on the black market, ranging from 250,000 to 300,000 SYP, adding to the living burden on residents, reducing their ability to meet basic needs, and increasing public dissatisfaction with government policies. Additionally, the growing reliance on the black market to obtain gas and other services contributes to further economic deterioration.

Regarding economic agreements with the regime's allies, the Syrian Battery and Liquid Gas Company in Aleppo signed a partnership memorandum of understanding with the Russian company Bogra Construction, committing the Russian company to supply, install, and equip a complete factory for the company. Despite a previously signed contract between the Syrian company and the Iranian company Tavan worth $41 million, the lack of progress under the contract indicates the fragility of Iranian investments in Syria and the competition from Russian investors in sectors entered by Iran. Reflecting the improvement in relations with Arab countries, the first Syrian Airlines flight arrived in Saudi Arabia after a year of the kingdom's approval to resume flights between the two countries. This move could open more avenues for cooperation between the two countries, positively impacting the regime's financial resources and encouraging other countries to resume air travel with Syria.

In northeastern Syria, the AANES decided to deprive summer vegetable farmers of their diesel fuel allocations, forcing farmers to buy it on the black market at high prices, which increased production costs and led to a 30% rise in local vegetable prices compared to previous years. These decisions are likely to reduce farmers' profit margins and their ability to continue farming. The lack of support could drive them to rely on the black market and pass on the increased costs to the prices of vegetables and fruits, adding to the financial burden on consumers and increasing poverty and deprivation among the population. This decision highlights the confusion in the administration's economic policies regarding planning and support for the agricultural sector, despite their adoption of socialist visions for regional management. In the same context, the quantity of wheat received this season in AANES areas has halved compared to the previous year due to the low purchase price set and farmers' reluctance to deliver their crops. The administration received only 766,000 tons of wheat, while expectations were around 1.5 million tons. The challenges facing farmers in Al-Hasakah have increased due to the lack of support and low local prices compared to the costs borne by farmers, forcing them to buy medicines and fertilizers in dollars on the black market, increasing costs and leading to a loss in the summer season. The decline in wheat received directly affects food security in the region. Farmers' reluctance to deliver their crops results in a growing trust gap between farmers and the "Autonomous Administration," reflecting the inefficiency of the administration's agricultural policies and its inability to meet farmers' needs.

In northern and eastern rural Aleppo, Syrian trucks resumed operations, transporting goods from border crossings with Turkey to northern Syria after a nearly complete halt lasting four years. Turkish trucks had stopped entering northern Syria due to the anger and protests in Syrian cities following the violence against Syrian refugees in Kayseri Province. The resumption of this activity is expected to create job opportunities for more than 700 Syrian truck drivers and around 500 workers in the region, helping to stimulate the local economy, reduce unemployment, and improve living conditions.

Significant Economic Cooperation Between The Syrian Regime and Iran During 2018-19

Executive Summary

Iran, a major ally and enabler of the Syrian regime, is increasingly engaged in competition over access to the Syrian economy now that there are new opportunities for lucrative reconstruction contracts. This report sheds light on the economic role played by Iran in Syria through its local representatives and Iranian businessmen. It also explores the (limited) impact of the European Union and U.S. Treasury sanctions on Iran's economic instruments in Syria.

Introduction

Iran has invested heavily in the protection of the Syrian regime and the recovery of its territories. Iran’s main objectives in Syria have been to secure a land bridge between its territory and Lebanon, and to maintain a friendly regime in Damascus. Much of Iran’s investment has been military, as it has financed, trained, and equipped tens of thousands of Shi’a militants in the Syrian conflict. But Iran has also made major financial and economic interventions in Syria: it has extended two credit lines worth a total of USD 4.6 billion, provided most of the country's needs for refined oil products, and sent many tons of commodities and non-lethal equipment, notwithstanding the international sanctions imposed on the regime. In exchange for its commitment to ensuring Assad’s survival, Tehran has expected and demanded large concessions in terms of access to the Syrian economy, especially in the energy, trade, and telecommunications sectors.

Key Iranian Companies

Iran has provided crucial economic assistance to the Assad regime in order to prevent its fall and to ensure that it can meet its fuel needs. In return, Iran demanded access to significant investment opportunities in key sectors of the Syrian economy, notably: state property, transportation, telecommunications, energy, construction, agriculture, and food security.

Since 2013, the Iranians have aided Assad through two main channels. First, it extended two lines of credit for the import of fuel and other commodities, with a cumulative value of over USD 4.6 billion. In order to position itself strategically as the lynchpin of the Syrian economy, Iran restricted the benefactors and implementers of these credit lines to its own national companies. It can thus continue to provide the regime with a lifeline in terms of goods and energy supplies, but in return it can control key parts of the Syrian economy.

The following list includes major Iranian companies that have announced a return to business-as-usual in Syria. Each brief overview gives a description of the company’s involvement in Syria, followed by basic information about the company.

Khatam al-Anbia Construction Base

Has demonstrated an interest in carrying out reconstruction work on Syria infrastructure.

Khatam al-Anbia Construction Base is involved in construction projects for Iran's ballistic missile and nuclear programs. It is listed by the UN as an entity of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), with a role “in Iran's proliferation-sensitive nuclear activities and the development of nuclear weapon delivery systems” (Annex to U.N. Security Council Resolution 1929, June 9, 2010). The company is under the command of Brigadier General Ebadollah Abdollahi.

Khatam al-Anbia conducts civil engineering activities, including road and dam construction and the manufacture of pipelines to transport water, oil, and gas. It is also involved in mining operations, agriculture, and telecommunications. Its main clients include the Ministry of Energy, Ministry of Oil, Ministry of Roads and Transportation, and Ministry of Defense.

Since the company’s founding in 1990 it has designed and implemented approximately 2,500 projects at the provincial and national levels in Iran. It currently works with 5,000 implementing partners from the private sector. An IRGC official recently revealed that a total of 170,000 people currently work on Khatam al-Anbia’s projects and that in the past 2.5 years it has recruited 3,700 graduates from Iran’s leading universities.

Company officials for Khatam al-Anbia include IRGC General Rostam Qasemi and Deputy Commander Parviz Fatah. Other personnel reportedly include Abolqasem Mozafari-Shams and Ershad Niya.

MAPNA Group

- Supplying five generating sets for gas and diesel operations (credit line)

- Construction of a 450 MW power plant in Latakia (credit line)

- Implementation of two steam and gas turbines for the power plant supplying the city of Baniyas (credit line)

- Rehabilitation of the first and fifth units at the Aleppo power plant (credit line).

MAPNA is a group of Iranian companies that build and develop thermal power plants, as well as oil and gas installations. The group is also involved in railway transportation, manufacturing gas and steam turbines, electrical generators, turbine blades, boilers, gas compressors, locomotives, and other related products. The Iran Power Plant Projects Management Company (MAPNA) was founded in 1993 by the Iranian Ministry of Energy. Since 2012, the group has been led by Abbas Aliabadi, former Iranian Deputy Minister of Energy in Electricity and Energy Affairs.

In 2015, MAPNA sealed a USD 2.5 billion contract, Iran’s largest engineering deal to date, to supply Iranian technical and engineering services for the construction of a power station in Basra in southern Iraq.

Mobile Telecommunication Company of Iran (MCI)

A contract to build Syria’s third mobile network (suspended).

MCI is a subsidiary of the Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI), which is partially owned by the IRGC. MCI brings in approximately 70 percent of TCI’s profits. MCI provides mobile services for over 1,000 cities in Iran and has approximately 66 million Iranian subscribers. It provides roaming services through partner operators in more than 112 countries.

Iranian Companies Active in Syria in 2019

Table 1: List of all Iranian companies with ongoing contracts in Syria - 2019

| Name | Arabic Name | Main Activity | Agreement | Headquarters Address |

| Safir Noor Jannat | سفير نور جنات | Food industries, detergents, and electronics | An old MOU dating back to 2015 to supply Syria with flour | No. 8, Mohamadzadeh st., Fat-h- highway 4Km. Tehran |

| Behin Gostar Parsian | بهين كستر بارسيان | Food industries | No information | Unit 5. No 14. Shahid Gomnam Street. Fatemi Sq. Tehran |

|

Peimann Khotoot Gostar Company جزء من مجموعة PARSIAN GROUP |

بيهين غوستار بارسيان | Electrical power, electronics, and technology | 2017 MOU with the batteries companies in Aleppo, the General Company for Metallurgical Industries in Barada, and Sironix, to carry out electricity projects in several locations in Syria. | Tehran Province, Tehran, District 22, No: 5, Kaj Blvd, 14947 35511, Iran |

| Feridolin Industrial & Manufacturing Company | شركة فريدولين | Electrical appliances | No information | ----- |

| Tadjhizate Madaress Iran. T.M.I. Co. | ---- | Decor and furnishings | No information | No. 198, Dr. Beheshti St., After Sohrevardi Cross Rd., 157783611, Tehran, Iran, Tehran |

| Trans Boost | ترانس بوست | Electricity | Electrical transformer station (230 66 20 kV) in the Salameh, Hama area | ---- |

| B.T.S Company | بي تي سي | Import and export, and commercial brokerage | No information | ------ |

| Nestlé Iran P.J.S. Co. | شركة نستله | Food industries | Supply of milk to Syria for the time being | 6th Floor, No.3, Aftab Intersection, Khoddami St., Vanak Sq., Tehran, Iran |

Recruiting Local Partners (Iran vs. Russia)

Iran and Russia have been competing over the reconstruction of Syria and the potentially lucrative investment opportunities that come with it because both countries hope to recoup some of their outputs from years of supporting the Assad regime and also because both hope to maintain their influence in the post-war era. Both Tehran and Moscow are therefore striving to win over major players in the Syrian political and economic spheres whom they hope to rely on to facilitate their business deals and ensure their respective interests. Consequently, both countries have established economic councils to oversee their ventures and to organize relations with their respective Syrian partners.

The following descriptions of the Syrian-Russian and Syrian-Iranian business councils cover their structures, the total number of members, the most prominent players, and the companies affiliated with their members.

The Syrian-Russian Business Council

The Syrian-Russian Business Council (SRBC) includes 101 Syrian businessmen and a number of Russian counterparts. It is divided into seven committees covering the main sectors of the economy:

- Engineering

- Oil and gas

- Trade

- Communications

- Tourism

- Industry

- Transportation

The Syrian membership of the SRBC includes many influential names, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Members of the Syrian-Russian Business Council

| Notable Names | Total Number of Businessmen |

| Samir Hasan (Chairman, SRBC) | 101 |

| Jamal al-Din Qanabrian (Deputy Chairman, SRBC) | |

| Mohammed Abu al-Huda al-Lahham, (Secretary, SRBC) | |

| Fares al-Shehabi (Businessman) | |

| Mehran Khunda (Businessman) | |

| Bashar Nahad Makhlouf (Businessman) |

Of these figures, three are particularly prominent:

- Jamal al-Din Qanabrian has served as a member of the Consultative Council of Syria’s Council of Ministers since 2017 (the Council presents proposals and consultations to the government on economic and legislative affairs). He is also a member of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

- Samir Hassan, the chairman of the Syrian-Russian Business Council, is a partner in Sham Holding Company, which is owned by Rami Makhlouf.

- Mohammed Abu al-Huda al-Lahham, also a member of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce, is believed to have strong ties with Dhul-Himma Shalish, the powerful Syrian construction mogul and cousin and personal guard of Hafiz al-Assad.

The SRBC also employs a number of Syrian businessmen of Russian nationality, most notably George Hassouani, who was formerly involved in oil and gas deals with ISIS.

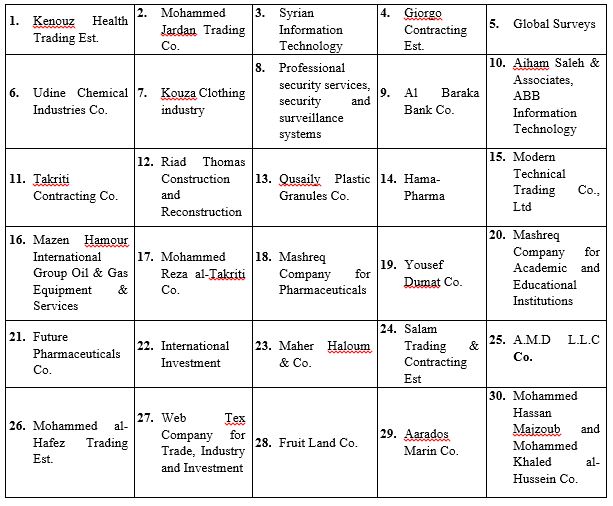

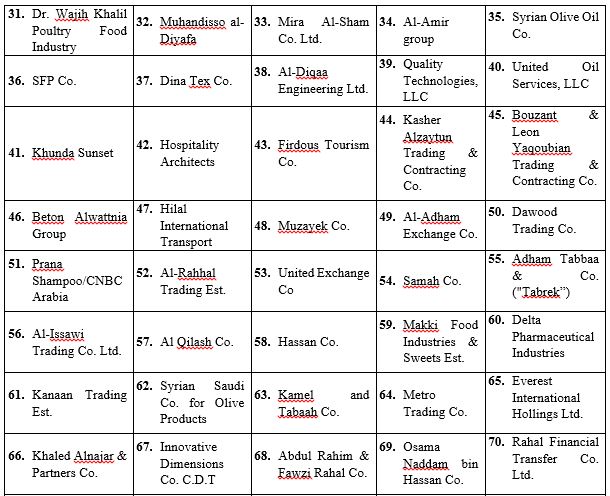

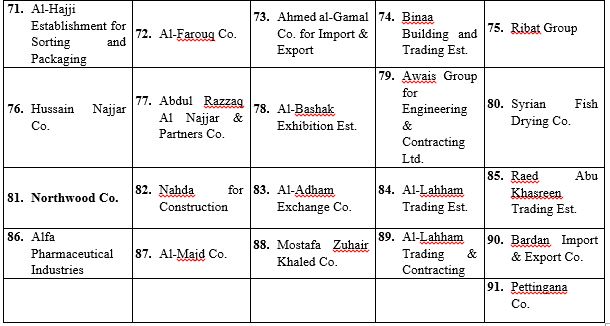

The number of Syrian companies included in the Syrian-Russian Business Council is estimated at 91. These companies are involved in import and export, general trade, textiles, clothing, petrochemicals, energy, and, in a small number of cases, private security operations (see Table 3).

Table 3: Companies in the SRBC

The Syrian-Iranian Business Council

By comparison, Iran has had less success with its business council venture than Russia. The Syrian-Iranian Business Council (SIBC) was established in March 2008, and was initially led by Hassan Jawad. It was reconstituted in 2014 with nine members, as shown below in Table 4.

Table 4: Members of the SIBC

| Notable Names | Total Number of Businessmen |

| Samer al-Asaad (President, SIBC) | b |

| Iyad Mohammed (Treasurer, SIBC) | |

| Mazen Hamour (Businessman) | |

| Osama Mustafa (Businessman) | |

| Hassan Zaidou (Businessman) | |

| Khaled al-Mahameed (Businessman) | |

| Abdul Rahim Rahal (Businessman) | |

| Mazen al-Tarazi (Businessman) | |

| Bashar Kiwan(Businessman) |

Some of these figures have significant economic influence:

- Mazen al-Tarazi is a prominent businessman with investments in the tourism sector as well as in real estate (including the project to redevelop Marota City in western Damascus). He has founded a number of companies in Syria, Kuwait, Jordan and elsewhere that offer services in oil well maintenance, advertising, publishing, paper trading, and general contracting. He also owns a number of newspapers, including Al-Hadaf Weekly Classified in Kuwait, Al-Ghad in Jordan, and Al-Waseet in Jordan.

- Iyad Mohammed is the Head of the Agricultural Section of the Syrian Exporters' Union.

- Osama Mustafa is a member of the People's Assembly, where he represents Rural Damascus Governorate. He served as Chairman of the regime’s Rural Damascus Chamber of Commerce between 2015-2018.

The number of companies owned by Syrian businessmen who are members of the SIBC board is estimated at 10 (see Table 5).

Table 5: Companies Owned by SIBC Members

|

Abdul Rahim & Fawzi Rahal Co. |

Al-Sharq Bank |

| Al-Shameal Oil Services Co. |

National Aviation, LLC |

| Rahal Money Transfer Co. |

Ebdaa Development & Investment Co. |

|

Mazen Hamour International Group |

Development Co. for Oil Services |

|

Dagher & Kiwan General Trading Co. |

Concord al-Sham International Investment Co. |

Because of the relatively small number of Syrian members of the SIBC, Iran is making additional efforts to woe Syrian businessmen. According to private sources, Syrian businessmen are seeking contracts with Iranian companies in return for being granted a share of the value of the contract. Table 6 shows key Syrian figures engaged with Iran.

Table 6: Syrian Businessmen Engaged with Iran

| Name | Position | Name | Position |

|

1.Faisal Talal Saif |

Head of the Suweida Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

2.Mohamed Majd al-Din Dabbagh |

Head of the Aleppo Chamber of Commerce |

|

3.Jihad Ismail |

Head of the Quneitra Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

4.Abdul Nasser Sheikh al-Fotouh |

Head of the Homs Chamber of Commerce |

|

5.Tarif al-Akhras |

Head of the Deir Ezzor Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

6.Osama Mostafa |

Head of the Rural Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

|

7.Adeeb al-Ashqar |

Merchant from the Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

8.Kamal al-Assad |

Head of Latakia Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

9.Albert Shawy |

Merchant |

10.Hamza Kassab Bashi |

Head of Hama Chamber of Commerce |

|

11.Amal Rihawi |

Director of International Relations at the Commercial Bank of Syria |

12.Mohammed Khair Shekhmous |

Head of the Hasaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

13.Elias Thomas |

Merchant |

14.Wahib Kamel Mari |

Head of the Tartous Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

15. |

Merchant |

16.Qassem al-Maslama |

Head of the Daraa Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

17.Saeb Nahas |

Merchant |

18.Aws Ali |

Merchant |

|

19.Ghassan Qallaa |

Head of the Federation of Chambers of Commerce |

20.Iyad Abboud |

General Manager of MOD |

|

21.Louay Haidari |

Merchant |

22.Ayman Shamma |

Merchant |

|

23.Mohamed Hamsho |

Secretary-General of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

24.Bassel al-Hamwi |

Merchant |

|

25.Mohamed Sawah |

Head of the Syrian Exporters Union |

26.Khaled Sukar |

Merchant |

|

27.Mohamed Keshto |

Head of the Union of Agricultural Chambers |

28.Sami Sophie |

Director of the Latakia Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

29.Marwa al-Itouni |

Head of Syrian Businesswomen |

30.Salman al-Ahmad |

Union of Syrian Agricultural Chambers |

|

31.Mustafa Alwais |

Rami Makhlouf 's partner |

32.Samir Shami |

Syrian Exporters Union |

|

33.Nahed Mortadi |

Merchant |

34.Gamal Abdel Karim |

Merchant |

|

35.Nidal Hanah |

Merchant |

36.Zuhair Qazwini |

Merchant |

|

37.George Murad |

Merchant |

38.Mohammed Ali Darwish |

Merchant |

|

39.Ghassan al-Shallah |

Merchant |

40.Nasouh Sairawan |

Merchant |

|

41.Mousan Nahas |

Merchant |

42.Anwar al-Shammout |

Owner of Sham Wings Co. |

|

43.Mounir Bitar |

Merchant |

44.Bashar al-Nouri |

Merchant |

|

45.Abdullah Natur |

Merchant |

46.Sawsan al-Halabi |

Director of a construction company |

|

47.Tony Bender |

Merchant |

48.Manaf al-Ayashi |

Foodco for Food Industries |

|

49.Maysan Dahman |

Merchant |

50.Khaled al-Tahawi |

Merchant |

|

51.Samer Alwan |

Blue Planet Energy Co. |

52.Saied Hamidi |

Oil and gas sector |

|

53.Roba Minqar |

Clothing industry |

54.Randa Sheikh |

Clothing industry |

|

55.Harout Dker-Mangi |

Merchant |

56.Alya Minqar |

Merchant |

Iran’s Role in Key Sectors

Iran seeks to obtain lucrative investment opportunities in different sectors of the Syrian economy, whether through tenders or monopolies. The main sectors in which Iran is trying to get full access are: agriculture, tourism, industry, reconstruction, and private security.

Agriculture

- Iran’s ability to match Russia’s investments in the Syrian agricultural sector has been significantly limited by the international sanctions imposed upon it. Since 2013 Iran has extended Syria two credit lines with the total value of USD 4.6 billion, aimed mostly at agriculture. Here is a list of Iranian investments in the sector:

- Supply of wheat since 2015 through the Safir Nour Jannat company"سفیر نور جنت".

- An agreement with the Syrian government to establish a joint company to export surplus Syrian agricultural products.

- An investment of USD 47 million for the second phase of implementation of the Iranian credit line to establish a plant to produce animal food, vaccines, and poultry products.

- A contract to build five mills in Syria at a cost of US 82 million in the provinces of Suweida and Daraa.

- A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Syrian General Organization of Sugar (Sugar Corporation) to establish a sugar mill and a sugar refinery in Salha in Hama in 2018.

- A 2018 MOU between the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Agriculture and the Iranian companies Nero and ITM for the import and distribution of 3,000 tractors.

Tourism

The tourism sector is considered one of the most vital sectors in the Syrian economy: it constituted a 14.4 percent share of Syria’s GDP in 2011 (US 64 billion). It has of course been heavily affected by the war, and tourism revenues decreased from SYP 297 billion (around USD 577 million) in 2010 to SYP 17 billion (around USD 33 million) in 2015, while tourism infrastructure suffered a loss of nearly SYP 14 billion (around USD 27 million) over that same period.

Tehran’s investment in Syria’s the tourism sector has been mostly in religious tourism. For instance, the Syrian Minister of Tourism signed a MOU with the Iranian Hajj Organization in 2015 to bring Iranians and others into Syria for religious tours. There are now estimated to be 225,000 religious tourists from Iran, Iraq, and the Gulf countries visiting Syria each year, and they bring in around SYP two billion (around USD 3.9 million) in revenue.

Industry

The industrial sector contributed 19 percent of Syria’s GDP in 2011, and has suffered losses estimated at USD 100 billion during the war. Iran has several industrial facilities in Syria. These are concentrated in the automobile sector, where they include the Syrian-Iranian International Motor Company and Siamco. Iran has also invested in the glass industry in Adra industrial city. The Iranian Saipa group announced a growth in sales of 11 percent in 2017 in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Azerbaijan. Car sales in Syria reached a significant level: although it was a third of 2018 sales in Iraq so far, 50,000 cars were sold in Syria last year.

Iran has tried to obtain contracts from the Syrian government in the industrial sector, and a number of MOUs have been signed. They include:

- A 2017 MOU between the Iranian company Bihin Ghostar Persian and General Organization for Engineering Industries to rehabilitate several companies: General Company for Metallic Industries–Barada (located in al-Sabinahis a town in southern Syria, administratively part of the Rural Damascus Governorate), SYRONICS (located in Damascus) and the battery factory in Aleppo.

- A 2017 MOU between the Syrian Cement and Building Materials Company in Hama and the Yasna Trading Company of Iran for the supply of spare parts.

In 2018, the Syrian-Iranian Business Council submitted a proposal for the participation of Iranian companies in the rehabilitation of Syria’s public industrial sector. In addition, the Iranian Ministry of Industry has expressed a wish to establish a cement production company in Aleppo as part of the second phase of implementation of the Iranian credit line.

Reconstruction and Infrastructure

The construction sector contributed 4.2 percent of Syria’s GDP in 2011 and then suffered a losses of USD 27 billion over the next six years. Syrian infrastructure has taken a similarly heavy hit as a result of the conflict, with losses valued at around at USD 33 billion, including over three million destroyed houses or housing units.

Iran’s interests in reconstruction—as with tourism—have a religious tinge and are mainly focused on the areas around sacred Shi’a shrines. For instance, Iran has been asking the Syrian regime for large concessions in Daraya, the old city of Damascus, Sayida Zainab, and Aleppo. Thus far Iran has mostly relied on Syrian intermediaries to purchase real estate, businessmen such as Bashar Kiwan, Mazen al-Tarazi, Mohammad Jamul, Saeb Nahas, Muhammad Abdul Sattar Sayyid, Daas Daas, Firas Jahm, Nawaf al-Bashir, and Mohammad al-Masha'li. Tehran has also relied on Syrian associations such as Jaafari, Jihad al-Binaa, the al-Bayt Authority, and “the Committee for the Reconstruction of the Holy Shrines" to expand and acquire new land in or near the holy sites in Damascus, Deir Ezzor, and Aleppo.

Sanctions against Syria and their Effect on Iran

The ongoing conflict in Syria has prompted international outcry and condemnation, as well as a long list of "red lines" and sanctions. The sanctions currently in place against Syria include an oil embargo, restrictions on certain investments, a freeze of the Syrian central bank's assets within the European Union, and export restrictions on equipment and technology that might be used for repression of Syrian civilians.

The problem with the sanctions on Syria is that they are ill suited to address the situation, in which sanctions are unlikely to work due to the ongoing war. The EU took significant steps very early in the Syrian conflict, essentially deploying its entire sanctions toolbox in less than one year, in contrast to its more common step-by-step sanctions approach. After a few years, the EU realized that this approach was rushed and ineffective and was forced to backtrack on some measures. This learning process showed the EU that an arms embargo is not necessarily the best first way to address a conflict situation.

Appendix

Syrian Companies Affiliated with Iran

| Name | Arabic Name | Main Activity | Agreement |

|

Abdul Rahim & Fawzi Rahal Co. |

شركة عبد الرحيم وفوزي رحال | معمل مواد بناء، تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير | حماة/طيبة الإمام، سوريا. |

| Ebdaa Development & Investment Co. | شركة إبداع للتطوير والاستثمار | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير | ريف دمشق |

|

Development Co. for Oil Services |

شركة التنمية لخدمات النفط | الخدمات النفطية | ------ |

| Obeidi for Construction & Trade | شركة عبيدي وشريكه للتجارة والمقاولات | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، المقاولات | فندق الداما روز بدمشق |

| Talaqqi Company | شركة تلاقي | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، مستحضرات التجميل | دمشق، كفرسوسة، عقار رقم 2463/ 87 |

| Nagam al-Hayat Company | شركة نغم الحياة | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، الخدمات الاستشارية | ريف دمشق، يلدا/ دف الشوك/ العقار رقم 507 |

| IBS for Security Services | ---- | --- | --- |

| Al-Hares for Security Services | شركة الحارس للخدمات الأمنية | خدمات الأمن والحماية الشخصية | دمشق |

| Mobivida L.L.C | شركة موبي فيدا | تجارة الأجهزة الإلكترونية، الهواتف المحمولة والإكسسوار، وتطوير خدمات الهواتف والإنترنت | دمشق |

| Al-Mazhor Company for Construction | شركة المظهور التجارية | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، المقاولات | دير الزور |

| Al Najjar & Zain Travel & Tourism Company | شركة النجار وزين" للسياحة والسفر | السياحة الدينية | نبل، مقابل مستوصف نبل عبارة الضرير / محافظة حلب |

Top Syrian Businessmen Affiliated with Iran

| Under EU Sanctions? | Under U.S. Sanctions? | Visited Abu Dahbi(UAE) in Jan 2019? | Main Position | Closeness of Relationship with Iran | Name in Arabic | Name |

| - | Yes | Yes | Secretary-General of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | High | محمد حمشو | Mohammad Hamsho |

| - | - | - | Member of Syrian Parliament | High | حسين رجب | Hussein Ragheb |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | حسان زيدو | Hassan Zaidou |

| - | Yes | Yes | Member of Syrian Parliament | High | محمد خير | Muhammad Kheir Suriol |

| - | Yes | Yes | Member of Syrian Exporters Union | High | إياد محمد | Iyad Muhammad |

| - | Yes | Yes | Manager of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | High | فراس جيكلي | Firas Jijkli |

| - | - | - | Chairman of the Supreme Committee for Investors in the Free Zone | High | فهد درويش | Fahd Darwish |

| - | - | - | Syrian Ambassador to Iran | High | عدنان محمود | Adnan Mahmoud |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Medium | عامر خيتي | Amer Khiti |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | علاء الدين خير بيك | Alla Ed din Khair Bik |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Low | جورج مراد | George Murad |

| - | Businessman | Low | منير بيطار | Munir Bitar | ||

| Yes | Yes | - | Works in SDF-controlled area and has relationship with Samir al-Foz | High | محمد القاطرجي | Mohamed al-Qtrji |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | علي كامل | Ali Kamil |

| - | - | Yes | Al-Matin Group General Manager | Medium | لبيب إخوان | Labib Ikhwan |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | سامر علوان | Samir Alwan |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Medium | ناهد مرتضى | Nahid Murtda |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Medium | مصان النحاس | Musan al-Nahas |

| - | - | Yes | Businessman | High | ربى منقار | Ruba Munqar |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Low | هاروت ديكرمنيجان | Harot Dikrmnjyan |