Administrative Divisions and the Conundrum of National/Local Identity Formation in Syria

This policy paper could not have been possible without contributions provided through the courtesy of:

![]()

Executive Summary

For decades the Syrian government has proclaimed that the demarcation of subnational administrative divisions was an apolitical process based on purely administrative and developmental considerations. A constant drive to homogenize the Syrian identity as part of a greater pan Arab identity has meant that local identity was hardly a subject of discourse, formal or otherwise. Beyond superficial references to folklore as a generic form of local identity, the subject was a political taboo.

Yet, the demarcation of administrative divisions was never entirely neutral. The management of the intricate procedures of delineating internal boundaries among governorates, districts, subdistricts, and municipalities, assigning nomenclature and toponymies, and determining the hierarchical status of administrative units was intertwined with manipulating local identities to build patronage networks for the central authorities and national elites at the local level. The haphazard process of creating new administrative boundaries in Syria developed divergent modes of accessing national development resources and fostered heterogeneous interplay between the national and local levels. Rather than consolidating a unified national identity, the rigid, non-transparent and highly centralised process of administrative design led to the creation of divergent identity markers and irreconcilable social solidarity models, which stand as key conflict drivers today.

This policy paper examines the impact of administrative-territorial subdivisions on the formation of local identity in Syria, the relationship between local and national identity, and, hence, the impact of administrative divisions on national identity. Based on extensive interviews with 76 key informants in all of Syria’s 71 districts, this policy paper draws on the data and results of a more comprehensive research published recently(1) It aims to track the construction and evolution of local identities as it relates to the process of demarcating administrative divisions from the initial moment of creating the Syrian state in the wake of the Sykes-Picot agreements to the aftermath of the conflict that erupted in 2011. It argues that the emergence of strong local identities is strongly related to the degree of connectivity the localities had to the centre. Contrary to common fears expressed by many in the central government and the opposition, strong local identities were not an antithesis to the emergence of a unifying national identity. Quite the reverse, the evidence points to the fact that the stronger the local identity, the more likely it was intertwined with the national one. What affected national identity negatively was marginalization and a centralized approach to enforcing national identity formation.

Historical Background

The Syrian administrative subdivision system follows a general tradition witnessed in many countries of the region since the Ottoman period. Two types of administrative hierarchies were deployed. On the one hand, there was the territorial order that divided the country into governorates, districts and subdistricts (mohavaza, mantiqa, nahiyeh). On the other hand, there was a municipal order of cities, towns, and townships (madinah, baldeh, baladiyeh). The jurisdictions given to each category shifted over time; however, the basic nomenclature and structure remained almost the same since independence in 1946.

Since the issuance of law 107, in 2011, the territorial order was scaled back considerably at the sub-governorate level, reducing it to policing and support functions to the governor. Thus, only the governorate (mouhavaza) level retains an elected council; the districts and subdistricts have no legal personalities, and the chief administrators are appointed centrally. The municipal order, by contrast, gained significance, and municipalities were imbued with legal personalities and had elected councils and mayors. The point of juncture between the two orders is the office of the centrally appointed governor, who chairs the elected governorate council and directly manages the administrators of the district and sub-district administrations. He also retains considerable oversight over the work of the elected municipal councils.

![]()

Figure 1: Schematic description of the administrative hierarchies in Syria today.

As it stands today, there are, 14 governorates, 71 districts and 288 sub-districts. On the other hand, the municipal composition as per the last adjustments done before the local elections of 2022 comprises 156 cities, 520 towns, and 754 townships. The evolution of this current administrative architecture was gradual, and emerged in waves. However, changes to the system involved not only the number of units but also the changing of toponomies and the authorities and accountability of each layer. Furthermore, the distribution of these units remained highly heterogenous as some governorates had a much larger number of subdivisions than others even when adjusting to per capita populations of the governorates.

The re-districting process was not part of a formal policy that emerged from free and open public debate. Indeed, until the issuance of the latest version of the National Framework for Regional Planning in 2022, there was not any formal recognition of the unbalanced distribution of cities and towns across the territory(2) Over the years, the dialogic relationship between local and national governance layers emerged in a haphazard manner and created heterogenous identity formations. The fear of opening debate on sectarian, ethnic, regionalist and ideological identities in Syria casted a long shadow over the subject of identity. Discussing local identity was equated with discussing sectarian and ethnic identities, a topic that was seen as an antithesis to a unified national identity. The demarcation of administrative boundaries was supposed to be a purely administrative process. The subsequent laws of 1956-1957-1971-2011 defined clear criteria for the hierarchy of administrative units based on population counts, socio-economic factors (defined primarily in economic and developmental terms) and proximity concerns. However, these laws were ambiguous on how boundaries are to be drawn. The process of demarcation of administrative units remained a prerogative of the executive branch of government without recourse to parliamentary oversight or referendum(3).

The process of consolidating the administrative divisions of Syria operated on different levels:

1. The designation of governorate level provincial units (mouhavaza): these were negotiated gradually during the French mandate on the traces of the old Ottoman Vilayet and Sanjak boundaries. When the French eventually abandoned the prospects of creating a federal state and negotiated the Franco Syrian Treaty in 1936, Decision No. 5 of 1936 was issued on the principle of drawing administrative units on purely administrative concerns. Governorate units (mouhavazat) thus had no political representation of their own. The order was codified in the post-independence era in the law of 1957. The number of mouhavazat increased gradually from 7 to 14; the last one being the designation of the capital city as a mouhavaza in 1972. There were no formal justifications given for ordinances to create new mouhavazat. However, our previous research suggests that the bulk were motivated by highly political interests to manage local identities and secure patronage for the central authorities. The central government was keener to create smaller provincial units with direct links to the capital than to decentralize power to larger governorates to allow them to serve their citizens in a better way(4).

2. The transformation of the nomenclature and toponymies of settlements, and territorial units: Here the drive was clearly ideologically driven to Arabize Kurdish, Syriac, Phoenician and other non-Arabized names starting during the union with Egypt but increasing in force from 1961 onward after the session from the union, and then later under the Baath. In addition to changing the names of cities, districts and sub-districts, most governorates lost their traditional names and were named after the major city in the mouhavaza. In border zones, the nomenclature was changed to provide a clear distinction and re-orientation of peripheral areas from their traditional connections to place names across the borders in neighbouring states towards the Syrian interior.

3. The demarcation of sub-governorate districts and sub-districts: The Syrian peripheral districts had to be disentangled from other territories of the Ottoman vilayets that were not incorporated into the Syrian territory in 1918. The French mandate focused on redefining these peripheral zones. A few changes happened in the immediate post-independence era. However, the main changes took place after the session from the union with Egypt and expanded during the early period of the Baath period into the presidency of Hafez Assad. Another, wave of new districts was created between 2007-2010. A few districts were created sporadically in between. The data from the research suggests that the initial waves of demarcating new districts was politically motivated either to segregate communitarian groups, or for nepotism purposes (to strengthen the personal patronage networks of leading Baath party leaders(5) Later districts created during Bashar al-Assad’s presidency seem to be more utilitarian in nature and focused on developmental and service objectives and less motivated by clear political or identitarian concerns.

![]()

| Figure 2: The change in the number of districts (mantiqa) from the Ottoman period till today. (Data sources: French era and Syrian government ordinances establishing the new mantiqas in Syria) |

4. The demarcation of municipal units: These were more fluid and were often created and changed at will. The orders for their creation came from different levels of authority, not necessarily linked to the letter of the law. The number of municipal units (cities, towns, and townships) remained more or less proportional to the population count in every governorate up till the year 2010. With minor variations, larger municipal units incorporated smaller units into their jurisdictions following the same pattern across all governorates. That process, while often reflecting some personal and identitarian biases remained generally administrative in nature till the issuance of law 107 for the year 2011. Subsequently the government seems to have manipulated the aggregation of smaller units into larger cities and towns following political and identitarian purposes. Zones of the country with rural populations that were loyal to the central state were rewarded with an increased number of towns and townships to allow for more chances of linking to national and provincial patronage networks. While rural zones of the country that were more hostile to the central government were annexed to the nearest cities and towns that remained more loyal to the central government.

|

Figure 3: The number of smaller municipal units in proportion to the total number of units in the governorates. Note that before 2010 there was a clear attempt at harmonizing the distribution of municipal units across all the governorates. Starting in 2011 there was a concerted effort to favour certain governorates with more small municipal structures and hence more access to political patronage of the State. (Data sources: the Syrian Statistical Abstracts for the Years 1983 and 2011; the Ordinance Number 1378/2011 and the Ordinance Number 1452/2022 issued by the Ministry of Local Administration and the Environment in Syria). |

Political motivations for administrative changes in Syria often revolved around the strategic control of communities. A notable tactic in this regard is gerrymandering, employed to manipulate the political landscape in favour of specific parties, especially the Baath Party after 1963. This was exemplified by the reassignment of towns like Harem in Idlib and Al-Qardaha in Latakia from one district to another despite their relatively small demographic size at the time. Additionally, political motivations can be traced to clientelist relationships maintained by key national elites or influential individuals – such as the transformation of the Al-Qadmus area into a district perhaps to consolidate the role of the influential Khawanda business family and to create a balance between the Ismaili and Alawi communities in the district. Another instance of this logic of redistricting was the establishment of six districts in Tartous to develop strong patronage networks to local communities; by contrast Al-Hasakah, several folds larger in surface area than Tartous and having double its population, has only four districts. In other instances, administrative subdivision was stalled in order to appease powerful figures, such as the decision not to elevate Manbij to a governorate status, likely to maintain the goodwill of the influential business and military elites of the Al-Shihabi clan who had a strong presence in the nearby city of Al-Bab, and which would have become annexed to its rival town of Manbij. The preference was for the two towns to remain in the sphere of the city of Aleppo as equal satellites rather than subordinating al Bab to Manbij.

Historical inertia also played an important role. In most cases once changes in administrative divisions were implemented, they tended to be irreversible or hard to reverse, even when the conditions for their formation were no longer warranted. Some towns lost their central economic and demographic role within their districts, yet they were maintained despite no longer adhering to the norms of establishing administrative subdivision. For example, Jarabulus was designated as a district during the French Mandate era (as it emerged from subdividing the border districts in northern Aleppo). Yet, it continues to hold this status, notwithstanding its relatively small area and population. This historical inertia in administrative districting underscores the enduring impact of past decisions on contemporary governance and regional identity. It also points to the strength of the patronage networks that are hard to dislodge once formed.

It seems though, that after 2000, the central government has reduced its reliance on the governorate and district levels to control political patronage in favour of municipal politics. Nonetheless, the establishment of new governorates, as well as ongoing modifications at the sub-governorate levels (regions and districts), and the reorganisation and redistribution of administrative units within cities, towns, and municipalities, significantly influenced the formation of local identities across Syrian territories. These changes have considerably impacted the stability of the communities within these units. In the subsequent part of this paper, the focus will be on the impact of these demarcations on the formation of local identity.

The Formation of Administrative Divisions and the Question of Identity

Consequently, examining such phenomena in the Syrian context is paramount, particularly considering the ongoing conflict since 2011and the current de facto division of the country. In the future, this importance is underscored by various factors: the sectarian and ethnic dimensions of the conflict, the fragmentation of Syrian governorates among different controlling entities, the imperative of establishing administrative frameworks to reinvigorate development amidst a deteriorating economy, the challenges of rebuilding societal cohesion and peace, the complexities in determining the original domicile of populations displaced by conflict since 2011 (or urban migration before 2011), and the criticality of considering decentralisation as a strategic approach to resolving the Syrian political stalemate.

The issue of local identify in Syria is particularly problematic. While the law speaks of the socio-economic dimension as the basis of defining administrative divisions and localities, in practice, as has been demonstrated in the first part of the paper, the central government resorted to demarcating local boundaries by manipulating intra-local sectarian, ethnic, tribal, and other forms of identities. Thus, rather than working to strengthen the cohesion of communities by facilitating the intermixing of divergent identity groups at the local level, the State (ever since the formation of the Syrian State and not just under the Baath) constructed new administrative structures in a non-transparent manner to foster these secondary identities while preventing localities from creating their own expressions of solidarity that would have transcended the identitarian divides. Thus, the local identity as a discursive construct is an unspoken contested field. It was supposed to produce a new political economy and social reality that would transcend Syria’s sectarian and ethnic divides, but in reality, it ended up subtly manipulating them and deepening the rifts.

Nonetheless, as shall be seen in the following sections, the construction of administrative boundaries did create new forms of identity and solidarity, perhaps not the intended ones, and certainly, as the research has demonstrated, they did not create homogenous results either. The findings of the qualitative survey that assessed the evolution of local identity will require careful verification through a more thorough quantitative analysis. However, the research, that the following findings were based upon, was rich with detailed information on the substance of local identities; and, more importantly, on the factors that lead to strong solidarity at the local level. The qualitative key informant interviews covering all 71 districts in Syria (as well as the sub-divisions of major cities) were based on questions related to the emergence of collective identity markers, standard toponyms and nomenclature, economic interests, managing and negotiating local differences, managing, and negotiating differences with adjacent districts, as well as managing the relationship with the governorate and the national levels with regards to social and identity problems. Qualitative results were translated into a set of criteria to define a basic barometer for the strength of identity markers and the sense of solidarity that communities had at each local, provincial (governorate), and national level. The initial research findings were presented in an Arabic language publication; however, a more thorough coding of the findings and a stronger correlation with quantitative data is in the works for future research.

While the study of local identity and its relationship with national identity could have focused on any of the various local scales, the researchers made an initial assumption based on previous work on the issue. They assumed that the provincial (mouhavaza) level administrative units were not proper vessels of local identity. In search of finer granularity for assessing the spread of local identity, they decided to select the district level as the basis of the study. At this scale, the relationship of cities to their hinterlands is still visible, and the socio-economic solidarity networks were perhaps the most visible. The research results confirmed a positive correlation in most cases with that scale of administrative demarcation on the formation of local identities. The team opted to avoid the municipal level at this research stage. The municipal level does not reflect the local rural-urban dynamics. It was also a system in constant flux, as shown above. While the governorate and district-level administrative demarcations were also constantly being modified, the rate of change was slower, allowing for more stable dynamics to form. The gradual impact of the administrative subdivisions could be traced more visibly at this level.

The Formation of National Identity

The constant shifting of the identity markers at the national level and the lack of universal adherence of local communities to a national identity framework is attributable to an amalgamation of both objective circumstances and political determinants.

Objective factors can be explained as follows:

- The nascent nature of the Syrian state: coupled with its origins in the post-Sykes-Picot order. This colonial pact is viewed unfavourably by most Syrians as an attempt at subdividing a larger national realm extending to other Levantine and Arab countries. This attitude perpetuates perceptions of Syria as a transient, diminutive entity born from a colonial project. Furthermore, there is a general societal distrust of the idea of administrative subdivision, as another colonial attempt at fragmenting the national realm. The legacy of the French mandate to divide Syria into small statelets plays into that fear.

- Supranational ideologies: Stemming from the point above, supranational political movements, encompassing Pan-Islamic, pan-Arab, and other ideologies advocating for the natural unity of Greater Syria (the Levant), or the Socialist International, have historically overshadowed Syrian political life. These movements have generally not prioritized cultivating a distinct Syrian national identity within its contemporary borders.

- Legacies of past identities: The social interconnectedness of Syrian communities with neighbouring communities in adjacent countries (Iraq, Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan) has fostered affiliations extending beyond national boundaries, especially for some border communities, further complicating the identity narrative.

Figure 4: Strength of belonging to the national identity and its identity markers. Qualitative responses to the survey were evaluated against a set of indicators and transcribed onto a heat map to show where a sense of strong belonging to a national order was manifest.

Political determinants were intricately linked to the strategies of successive political regimes, and they changed accordingly:

- Efforts by ruling elites to foster a supranational Arab identity to enhance their legitimacy in leading Syrian polity: This inadvertently undermined the significance and visibility of distinct Syrian identity markers (flags, personalities, slogans, etc). National identity was experienced by society through the prism of allegiance to the ideological tenets of the ruling elites, creating a sense of state-defined national identity rather than one grown organically through the cultural innovation and genius of the society. Thus, the general populace's sense of national identity is profoundly impacted by people’s interaction with State institutions and policies and was confounded by perceptions of weak governance and corruption. Or conversely it was perceived strongly when local communities had strong direct patronage ties to the national elites or national institutions. Thus, it is not uncommon to see some small islands of adherence to national identity among communities such as Al-Bab and Raqqa city. Both are examples of localities that had strong connections of patronage or business with the centre.

- The constant leveraging of external political projects: including the constant focus on the regional Arab-Israeli conflict de-legitimized local priorities and concerns and led to a systematic weakening of the concept of citizenship to a national order. Dissent was discouraged and at times violently put down, thereby diluting a strong sense of national allegiance, as the central state was seen as synonymous to the repression by national elites. This was clearly the case in the cities of Hama, Jisr al-Shougour, Lattakiyah, and Haffeh for instance.

- The deliberate marginalization of certain regions: notably Northwest and Northeast Syria, left many groups feeling disenfranchised. The same goes for many rural and desert areas that were subservient to the economy and patronage of major cities. Empirical evidence from the research suggests that geographical proximity to the capital was a significant factor in consolidating a sense of national identity. This phenomenon may be attributed to the symbolic role of the capital in national identity construction and the employment of a substantial number of residents from neighbouring governorates in state institutions located in the capital. The town of Harem and many parts of Dara’a and Sweidah fall into that category.

- The centralization of the political system: and a lack of encouragement for forming cross-provincial networks of local councils and civil society left all attention focused on the directives and priorities of the capital. The main exception would be unions that were predominantly controlled by the Baath Party. They provided some chances for networking and interaction between localities but as they were under the ideological control of the Baath, they did not encourage organic expressions of national identity. However, connection to the Baath afforded a higher level of social mobility and allowed for physical contacts and even internal migration to other parts of the country, encouraging a stronger appreciation of the national territory.

The Complex Dynamics of Local Identity

The research methodology used, and the data collected for the research relied on a clear distinction between social and local identities. The former pertains to identification with a social category, such as ethnicity, religion or sect, class, clan, family, or other social groupings. Conversely, local identity is intrinsically connected to a specific geographical locale, encompassing various social groups interacting in the same space. Further, the research team differentiated between local political identity, which confers specific political rights upon its bearers, and local cultural identity, intimately tied to its adherents' customs, traditions, practices, and adoption of specific identity markers. The researchers’ focus was on local cultural identity, conceptualized as the individuals' emotional and conscious connection to a specific geographical area rather than belonging to a specific social or identitarian group. It was deemed essential to correlate the spatial designation of supposedly neutral administrative divisions with the local cultural praxis that ensued in those local units.

The local connection is fostered through economic and social bonds established via unique modes of production, customs, and traditions that differentiated them from other locations with whom they may have shared other common social affinities. However, the research team was clear not to rigidly confine the definition of the “local” when investigating local cultural identity. People interviewed were for the most part not limited in their responses to a fixed spatial boundary when they described their localities. The “local” may be specific to a small city, such as Salamiyah in Hama Governorate, or extend to a geographical region, exemplified by the cities and towns of Qalamoun, including Deir Atiya, Al-Nabak, Jairud, and Yabroud. In some cases, it extended for beyond the governorate level for certain respondents.

Figure 5: Strength of local identity markers. Qualitative responses to the survey were evaluated against a set of indicators and transcribed onto a heat map to show where a sense of strong belonging to a local order was manifest.

The determinants of local identity included the respondents’ cleat to conceptualise the geographical extent of their “local” area, identify local symbols and identity markers (such as prominent figures, landmarks, or significant events), recognize dialects, adhere to certain cultural expressions, as well as the appreciation of the customs, traditions, and rituals practiced within that area.

Several factors were found to contribute to strengthening local identity:

- Social homogeneity: The degree of social homogeneity within a society (in terms of clans, sects, classes, etc.) is directly proportional to the strength of its local identity. While some heterogenous localities seemed to have strong local identities resulting from long traditions of managing and negotiating their differences, the general stability of the social order in the locality is key to the emergence of a strong identity.

- Legacies and renown: The prominence of a locality and the fame of its identity markers, whether due to historical events such as being the birthplace of the Great Syrian Revolution for Dara’a, archaeological or natural landmarks such as the Aleppo Citadel and the Ugarit alphabet, or distinctive regional traits like the humour in Homs, amplifies their local identities.

- Institutional thickness: Regions with a longer history of institutional development tend to have stronger local identities. For instance, the identity of modern Raqqa (one of the late governorates to be created) is less pronounced than that of Aleppo or Latakia. By contrast a place like Raqqa tends to have a stronger national identity as it had stronger connection to the centre directly and resolved its administrative problems via a more direct access to central patronage. Newly created districts were the clearest examples of weak local identity as they were formed by extracting their communities from other previous administrative districts, often creating heterogenous social groupings and confusion of connection to administrative services, such as in the case of Tal Dao.

- Production and transportation connectivity: The extent to which the dynamics of economic production and the existence of value chains necessitated interaction with external entities and a loss of economic centrality inversely affects local identity. Similarly, limited transportation connectivity with surrounding areas can at times reinforce local identity in a negative sense. By contrast areas and district that still depended on agriculture as the main stipends for economic wealth tended to have very strong local identity.

![]()

Figure 6: Strength of identity markers at the governorate level. Qualitative responses to the survey were evaluated against a set of indicators and transcribed onto a heat map to show where a sense of strong belonging to a local order was manifest.

The general hypothesis that the governorate level was not a strong lever for local identity was in evidence at this stage of the research. When asked about the governorate level as a harbinger of local identity, the results were often clearly negative. The governorate level which is the most powerful level in the Syrian hierarchy of local government, seems to have failed to foster a sense of community. While some of the more recent districts have failed to foster a strong sense of locality, most governorates have manifestly failed to do so, Homs being one strong exception, at least for the western parts of the governorate. There are other minor exceptions, like Dara’a, Deir Zorr and Sweidah, who maintain strong governorate level identity, perhaps as a result of their sectarian or tribal structures. Governorate-level identity is generally strong in larger cities, especially the city centres of the governorates. However, in most rural areas, the subjugation of the local level to the hierarchical administration of major cities has created a reverse sense of belonging.

It should be noted however, that the pre-conflict dynamics are quickly changing. Idleb that was once one of the least developed in terms of its governorate level dynamics before 2011 is showing a strong tendency to develop a strong governorate level identity since. The prospects for how the identity formations have been transformed during the conflict awaits new research and falls outside the scope of this paper.

On the Relationship Between Local and National Identities

The interplay between national and local identities can be conceptualised along six distinct dimensions: predominance of local over national identity, predominance of national over local identity, parity between national and local identities, concurrent weakness in both national and local identities, exclusivity of national identity, and exclusivity of local identity. Empirical findings from the study suggest that, in most instances, one identity has a pronounced presence coupled with a secondary importance for of the other. Notably, instances of exclusive national or exclusive local identity were not evidenced in the sample. Likewise instances of mutual exclusivity are very limited. The case of Shaddai is the exception that proves the rule, as a substantive part of that local consisted of people that were moved from the areas that were flooded after the construction of the Euphrates dam. Their affinity with the central government that displaced them and the new hard geography where they were displaced created a negative appreciation of both identity levels.

The interview data indicated a strong correlation between strong local and national identities. This implies that individuals often perceive themselves as belonging to their localities and to Syria simultaneously. A robust local identity is indicative of a deep emotional attachment to one's place of origin or settlement, conferring a sense of uniqueness to the inhabitants of that locality. Concurrently, it seems to also signify an emotional bond with the nation, embodying a sense of protection and belonging. Thus, integration of the two levels emerges as a salient characteristic in the nexus between local and national identities. Although this matches the findings of the theoretical literature and evidence from other countries, this cannot be taken as a fact and should be tested quantitively in more detail in the future.

Another finding is that the conflict between local and national identities arises predominantly when the latter is perceived as undermining or threatening the former. In such scenarios, local identity challenges the national identity when there is a perception that national identity seeks to subsume or replace it (the case of Lattakiyah, of Haffeh and Hama discussed above). In that sense, national identity shifts from being a protective umbrella to be perceived as threat or imposition on local communities, while local identity transitions from a source of pride to a bastion of self-defence. Such situations are also indicative of populist discourses on identity. Identity markers may gain in relevance but mitigating measures to manage difference between social groups and ensure stability and cohesion recede in importance.

In contexts where local identity is weak, adopting national identity becomes transactional. The potential for adopting a national identity in that case is clearly contingent on perceived benefits from the government and its patronage networks, as the case of Raqqa exemplifies. Conversely, both identities may remain underdeveloped without such incentives, as observed in Al-Shaddadi above. Peripheral zones sometimes exhibit such conditions. Some frontier and border districts demonstrated a lack of attachment to the national identity as proximity to State favours and patronage was limited. In some incidences connection to social and economic networks across the border were more prominent. This worked against both the local and national sense of belonging. The localities along the border with Lebanon are a case in point, where the economy is tied to smuggling networks across the border. The same was observed in other non-peripheral areas; national identity appears to be more diminished in areas with a weaker local identity. The evidence at hand does not allow for drawing strong statements of causality. However, a principle initial finding of the research is that proximity to the political, or geographical centre, bolsters national identity. This is largely due to transactional and pragmatic considerations perhaps more than other factors such ideological ties and cultural affinities.

In that regard, identity formation should not be seen as a natural process; it cannot be taken for granted as it is constantly being re-constructed. The creation of administrative divisions is perhaps one of the most instrumental factors in putting localities on the radar of the capital. While primarily designed to foster political clientelism and patronage networks for the central government and its elites, it has also allowed for trickling of resources from the centre to the local level for developmental purposes creating a leverage for a strong national identity. By contrast, geographically or politically marginalised areas often correlate with a weakened national identity. The main conclusion for the research is that a forced centralisation of the ideological construction of national identity coupled with marginalization has undermined national identity rather than reinforced it.

Recommendations

This paper has reviewed conditions in Syria from before the conflict. Many of its arguments must be revisited after 13 years of hostilities. Yet, the evidence is clear: The reconstruction of a national identity for a post-conflict Syria will have to be considered very carefully from the bottom up, and not just from the top down. Many factors will come to play in re-negotiating the relationship of the local to the national level to ensure stability and non-recurrence of violence in the future. The fine tuning of the design of the administrative divisions will have to be considered as a key factor. The demarcation of administrative boundaries is essential not only to balance the distribution of antagonistic social groups but to effectuate a fair and equitable distribution of resources and access to national polity. The process must be transparent and mutually acceptable to Syrians to avoid the manipulation of central/local relations on the basis of patronage and clientelism. National and local identities are not at odds as many have come to conclude as a result of the war, indeed, their mutuality is the corner stone to sustain peace in the future.

In fostering a cohesive national identity and a balanced co-creation of local and national identities in Syria, this paper proposes the following recommendations to address national identity formation through various constitutional, institutional, and socio-political dimensions.

The Parameters of Syrian National Identity: It is imperative that Syrians should work to consolidate the building of a social compact among them as citizen living in one State that recognizes their full and equal citizenship with all that entails of rights and obligations. Defining the parameters of citizenship as a balance between individual rights and group rights will not be an easy task. Syrians are advised to consider the following:

- Accepting the Syrian state in its current borders as the harbinger of national identity: Syrians will always have aspirations for belonging to a supranational identity. This will not likely change over the short time. But Syrians need to understand that failure to build a mutually acceptable Syrian national identity today will not lead to the formation of their supranational dreams. Quite the reverse, the fragmentation of national identity today will only lead to the permanent and irreversible division of the country based on the su-national de facto division of the country.

- Inclusivity in national identity: While the State needs a unifying national identity, this should not happen at the expense of the diversity of local identities. The two are not mutually exclusive. National identity should recognise and celebrate the diverse tapestry of Syrian communities, their identity markers, and their values.

- Respect for local identities: The focus of the debate concerning the plurality of identitarian groups (religious, sectarian, ethnic, class, clan, etc.) has diverted attention towards irreconcilable differences. By contrast, shifting the focus to the local identity that encompasses and aggregates diverse identitarian groups and works to bridge the gaps between them could provide a workable alternative. Localities have complex dynamics of interaction among different social groups. They have evolved tried and tested mechanisms for the reconciliation of differences. Social cohesion will be fostered through reviving local collective identities rather than the populist portrayal of Syria as a stagnant mixture of distinct and irreconcilable identitarian components or groups.

National and Constitutional Dialogue on National Identity: The current construction of national identity, as defined by the Syrian political and constitutional order, will recreate conditions of exclusion as identity is perceived as an a priori and predefined construct, is heavily controlled and proscribed from the top down, and is limited to a rigid definition of national identity markers. This definition of identity fails to adequately reflect the diverse social and local nuances of Syrian identitarian groups and even the differences inside each group. But more problematically, it also heeds little to the need for balancing the relationship between the centre and the local levels politically, administratively, economically, and socially. Key Issues to consider:

- A national dialogue focused on the national identity is imperative: This needs to be fostered both in the track 1 process but perhaps the debate needs to also be opened to other tracks. The debate should go beyond the pre-determination of national identity markers as envisioned by the Government nominated delegation to the Constitutional Committee, or the creation of a more inclusive construct of national identity that resonates with identitarian groups, as envisioned by the delegation of the Opposition Negotiation Commission. Very rich alternatives are possible when considering the local level as place for resolving identity tensions.

- Unpack the complex relation between the centre and the local: through a comprehensive revision of the issue of decentralization in Syria, the design of the administrative order, the distribution of resources and the creation of transparent relations between the central and local levels. This should be an essential entry point for the constitutional debate in the Syrian political process.

Institutional Levers for National Identity: National and local identities are not simple by-products of constitutional design. In fact, the most relevant factor for identity construction is the daily praxis of institutions and not their normative design per se. Institutional functions, administrative structures, and the day-to-day work of formal and informal governance bodies are of utmost importance. The reform of institutions to enhance their ability to reflect a transparent process of sustaining national identity and creating the balance with local identities will be of utmost relevance in the post-conflict period. The institutional design should encompass:

- Economic empowerment and decentralization: Strengthen the economic capabilities of localities and launch a process of decentralisation that fosters transparent allocation of authorities and responsibilities on the basis of subsidiarity. Preventing economic marginalization is essential to bridging the divide between the local and national identities.

- Allow for local-to-local interaction: It is posited that extreme centralisation poses a greater threat to social cohesion and the emergence of a unified national identity than a carefully designed process of decentralisation that fosters possibilities for the local administrations to enhance their collective bonds and work closely with each other and with the centre to resolve problems of local identity. The experience demonstrates that these issues, left to the prerogative of the centre alone, did not create a better adherence to national identity. To the contrary it allowed for central elites and their ideology to play with local patronage networks and increase social and identitarian tensions at the local level.

- Administrative division planning: The design of the administrative divisions in Syria is at the core of conflict dynamics. The conflict has fostered new territorial divisions. There is a need to formulate a strategic plan for transparently managing administrative divisions respecting local identities and their sensitivities. A careful balance should be struck between the need for creating new administrative divisions to better manage local identity and the need to avoid administrative divisions as a tool for rentier distribution of resources to foster patronage and clientelist networks for national elites. New governorates may be in order such as Qalamoun, Ghouta, Palmyra, Qamishli, Manbij, and potentially Salamiyah.

- Avoiding the populist definition of identity: The process of administrative demarcation should be entirely distinct from the calls for managing identity issues through negotiations among identitarian groups (or identitarian components) at the national level. Such an approach is only likely to replace national level elites with a new crop of sectarian, ethnic and tribal populist leaders.

- The socio-economic logic of administrative design: The feasibility of new administrative units from an economic point of view should be considered to avoid the creation of redundant layers of governance that can only work to foster corruption and clientelism. Moreover, aggregating local economic resources and social capital in a transparent manner is vital in creating sustainable and stable local identities. Social capital will be one of the most important resources in the reconstruction of the country in the post conflict.

Preservation of local identities: At a first instance this should entail avoiding actions that could erode local identities, such as altering the names of localities or modifying their administrative boundaries without proper consultations and agreement among the local communities. But beyond that, there is a need to designate resources, to support communities to generate positive expressions of their local identity, to protect their identity markers, preserve their heritage assets, and to ensure that identity is constantly being allowed to represent the living spirit of the local communities.

.

Palestinians of Syria.. Violation of Rights and Identity Challenges

Executive Summary

- Palestinian refugees in Syria have not been spared from the relentless violent policies of the Syrian regime. Gross violations have been committed against them, and they have experienced a rapid erosion of the rights afforded to them by both Syrian and international law. As of October 2019, documentation indicates that 3,995 Palestinian refugees in Syria—mostly young men—have been killed and 1,768 Palestinian refugees have been detained in the regime’s security and intelligence prisons. More than 568 Palestinian detainees of the victims, both male and female, have been tortured to death in regime detention. In addition, there have been 205 casualties who died due to starvation, lack of medical care, siege, and the semi-complete destruction of the Palestinian refugee camps of Daraa, Sbeineh, al-Sayida Zainab, and Handarat; the destruction of large parts of the camps in Khan al-Sheih and al-Husseinyeh; and the complete destruction of al-Yarmouk camp. Furthermore, more than 200,000 Palestinians have fled across the Syrian borders.

- Palestinian refugees in Syria have suffered and continue to suffer from intense threats and risks to their real property rights. Some of the Syrian laws issued in recent years provide cover for the government to strip owners of their own property. In addition, the tight security grip prevents the return of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) to their original homes in the Palestinian camps. As a result, Palestinian refugees in Syria have experienced large-scale property expropriation for political purposes. At the same time, the USA and European countries still refuse to participate in the reconstruction of Syria until a political solution is reached and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is failing to shoulder the burden of rebuilding Palestinian camps due to its financial deficit and challenges to its very mandate.

- The relationship between UNRWA and the General Administration for Palestinian Arab Refugees (GAPAR) was governed by the checks and controls through which the Syrian authorities specified UNRWA’s role and the its geographical scope of work in Palestinian camps and communities. As a result of these restrictions and controls, UNRWA’s services have failed to reach the large number of refugees who need them, depriving thousands of refugees from the services and aid.

- Challenges facing the continuation of UNRWA’s mandate cannot be separated from the legal status of refugees, as UNRWA maintains the comprehensive civil record of the refugee assets in Palestine. This is considered the primary archive of transformations in their demographic status and a crucial source for confirming the international legal dimensions of their asylum.

- During the recent turmoil in Syria, the Palestine Liberation Organization’s (PLO) declared position of political neutrality towards the Syrian issue did nothing to prevent a series of marked violations of the civil rights of refugees. A profound shift in refugees’ perception of the PLO can be observed by looking at the positions of PLO’s leadership at various milestones in the conflict. Positions issued by PLO leaders contributed to covering up responsibility for the parties involve in such crimes as indiscriminate bombardment, siege, starvation, and detention of people in al-Yarmouk camp. Meanwhile, Palestinian factions loyal to the regime such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command, As-Sa’iqa, Fatah al-Intifada, Jabhat al-Nidal al-Sha'bi, and other militias, in addition to the Palestine Liberation Army, all participated in fighting alongside the regime and helped it impose the siege on al-Yarmouk camp.

- This research reveals the magnitude of the complex problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Syria by examining the paths of their migration and escape from the bloody war—which Palestinians in Syria lived through as their second catastrophe, or “Nakba”—and the crises and violations they have faced in neighboring countries and other places of exile. The failure of many States to comply with the 1951 Refugee Convention has magnified the suffering of refugees by denying them protection and aid, leaving them with limited options. As a result, many have found themselves and deprived of their rights and at risk of deportation and refoulement. This research presents various examples of the violations that Palestinian refugees have been exposed to due to their vulnerable legal status, such as: being detained in airports and holding centers for foreigners for long periods of time; being deported back to Syria or the threat thereof; being treated as foreigners or tourists rather than refugees fleeing a war; not being offered humanitarian assistance that would mitigate their suffering; etc.

- The risks and challenges facing the “Palestinian-Syrian identity” highlight the extent to which legal status and its transformations impact the holders of this identity. They face difficulties rebuilding and restoring their identity, not only in terms of place and collective memory, but also in terms of the disintegration of their legal status. This reveals a recognition of the importance of legal status and its implications for the configuration of identity and its open questions. It is especially so with the ambiguity of the future in Syria in general, and of options related to the legal status of Palestinians in Syria, in particular, opening the floor for multiple risks and challenges putting much doubt and posing major questions to the identity dialectic.

- One of the most important recommendations stemming from this research is to expose the Syrian authorities’ responsibility for the degradation of the legal status of the Palestinians of Syria. There should be a shift from monitoring and documenting violations to encouraging victims of these violations to take their cases to court in countries whose national laws allow for universal jurisdiction in such cases where the perpetrators committed war crimes and crimes against humanity. The research further recommends the formation of a special committee or commission to advocate for the property of Palestinian refugees in Syria and calls on all host countries and bodies concerned with managing the affairs of Palestinians of Syria to grant them their right of confirming their original Palestinian citizenship in all documents, records, and data. The findings demand that the PLO address the adverse effects of the lack of representation of refugees and urges the PLO to set up institutional mechanisms to unite the diaspora and represent their demands and rights. The research also emphasizes the importance of the persistence of UNRWA, the continuation of its foundational assistance mandate, and the exposure of schemes aimed at eliminating the cause of the refugees and eradicating their right of return to their homeland in Palestine as per UN General Assembly Resolution 194 (III).

- In light of the magnitude of issues facing Palestinians in Syria, including the disintegration of their legal status, the continued attrition of their presence inside Syria, and the difficulties faced by those forced to migrate and flee to other countries, all attempts to remedy and restore their status will depend on the course of and end to the conflict in Syria. There appear to be few current approaches or solutions that may reassure Palestinians about the future of their presence in Syria and move them towards a more secure legal status that guarantee their rights.

Significant Economic Cooperation Between The Syrian Regime and Iran During 2018-19

Executive Summary

Iran, a major ally and enabler of the Syrian regime, is increasingly engaged in competition over access to the Syrian economy now that there are new opportunities for lucrative reconstruction contracts. This report sheds light on the economic role played by Iran in Syria through its local representatives and Iranian businessmen. It also explores the (limited) impact of the European Union and U.S. Treasury sanctions on Iran's economic instruments in Syria.

Introduction

Iran has invested heavily in the protection of the Syrian regime and the recovery of its territories. Iran’s main objectives in Syria have been to secure a land bridge between its territory and Lebanon, and to maintain a friendly regime in Damascus. Much of Iran’s investment has been military, as it has financed, trained, and equipped tens of thousands of Shi’a militants in the Syrian conflict. But Iran has also made major financial and economic interventions in Syria: it has extended two credit lines worth a total of USD 4.6 billion, provided most of the country's needs for refined oil products, and sent many tons of commodities and non-lethal equipment, notwithstanding the international sanctions imposed on the regime. In exchange for its commitment to ensuring Assad’s survival, Tehran has expected and demanded large concessions in terms of access to the Syrian economy, especially in the energy, trade, and telecommunications sectors.

Key Iranian Companies

Iran has provided crucial economic assistance to the Assad regime in order to prevent its fall and to ensure that it can meet its fuel needs. In return, Iran demanded access to significant investment opportunities in key sectors of the Syrian economy, notably: state property, transportation, telecommunications, energy, construction, agriculture, and food security.

Since 2013, the Iranians have aided Assad through two main channels. First, it extended two lines of credit for the import of fuel and other commodities, with a cumulative value of over USD 4.6 billion. In order to position itself strategically as the lynchpin of the Syrian economy, Iran restricted the benefactors and implementers of these credit lines to its own national companies. It can thus continue to provide the regime with a lifeline in terms of goods and energy supplies, but in return it can control key parts of the Syrian economy.

The following list includes major Iranian companies that have announced a return to business-as-usual in Syria. Each brief overview gives a description of the company’s involvement in Syria, followed by basic information about the company.

Khatam al-Anbia Construction Base

Has demonstrated an interest in carrying out reconstruction work on Syria infrastructure.

Khatam al-Anbia Construction Base is involved in construction projects for Iran's ballistic missile and nuclear programs. It is listed by the UN as an entity of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), with a role “in Iran's proliferation-sensitive nuclear activities and the development of nuclear weapon delivery systems” (Annex to U.N. Security Council Resolution 1929, June 9, 2010). The company is under the command of Brigadier General Ebadollah Abdollahi.

Khatam al-Anbia conducts civil engineering activities, including road and dam construction and the manufacture of pipelines to transport water, oil, and gas. It is also involved in mining operations, agriculture, and telecommunications. Its main clients include the Ministry of Energy, Ministry of Oil, Ministry of Roads and Transportation, and Ministry of Defense.

Since the company’s founding in 1990 it has designed and implemented approximately 2,500 projects at the provincial and national levels in Iran. It currently works with 5,000 implementing partners from the private sector. An IRGC official recently revealed that a total of 170,000 people currently work on Khatam al-Anbia’s projects and that in the past 2.5 years it has recruited 3,700 graduates from Iran’s leading universities.

Company officials for Khatam al-Anbia include IRGC General Rostam Qasemi and Deputy Commander Parviz Fatah. Other personnel reportedly include Abolqasem Mozafari-Shams and Ershad Niya.

MAPNA Group

- Supplying five generating sets for gas and diesel operations (credit line)

- Construction of a 450 MW power plant in Latakia (credit line)

- Implementation of two steam and gas turbines for the power plant supplying the city of Baniyas (credit line)

- Rehabilitation of the first and fifth units at the Aleppo power plant (credit line).

MAPNA is a group of Iranian companies that build and develop thermal power plants, as well as oil and gas installations. The group is also involved in railway transportation, manufacturing gas and steam turbines, electrical generators, turbine blades, boilers, gas compressors, locomotives, and other related products. The Iran Power Plant Projects Management Company (MAPNA) was founded in 1993 by the Iranian Ministry of Energy. Since 2012, the group has been led by Abbas Aliabadi, former Iranian Deputy Minister of Energy in Electricity and Energy Affairs.

In 2015, MAPNA sealed a USD 2.5 billion contract, Iran’s largest engineering deal to date, to supply Iranian technical and engineering services for the construction of a power station in Basra in southern Iraq.

Mobile Telecommunication Company of Iran (MCI)

A contract to build Syria’s third mobile network (suspended).

MCI is a subsidiary of the Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI), which is partially owned by the IRGC. MCI brings in approximately 70 percent of TCI’s profits. MCI provides mobile services for over 1,000 cities in Iran and has approximately 66 million Iranian subscribers. It provides roaming services through partner operators in more than 112 countries.

Iranian Companies Active in Syria in 2019

Table 1: List of all Iranian companies with ongoing contracts in Syria - 2019

| Name | Arabic Name | Main Activity | Agreement | Headquarters Address |

| Safir Noor Jannat | سفير نور جنات | Food industries, detergents, and electronics | An old MOU dating back to 2015 to supply Syria with flour | No. 8, Mohamadzadeh st., Fat-h- highway 4Km. Tehran |

| Behin Gostar Parsian | بهين كستر بارسيان | Food industries | No information | Unit 5. No 14. Shahid Gomnam Street. Fatemi Sq. Tehran |

|

Peimann Khotoot Gostar Company جزء من مجموعة PARSIAN GROUP |

بيهين غوستار بارسيان | Electrical power, electronics, and technology | 2017 MOU with the batteries companies in Aleppo, the General Company for Metallurgical Industries in Barada, and Sironix, to carry out electricity projects in several locations in Syria. | Tehran Province, Tehran, District 22, No: 5, Kaj Blvd, 14947 35511, Iran |

| Feridolin Industrial & Manufacturing Company | شركة فريدولين | Electrical appliances | No information | ----- |

| Tadjhizate Madaress Iran. T.M.I. Co. | ---- | Decor and furnishings | No information | No. 198, Dr. Beheshti St., After Sohrevardi Cross Rd., 157783611, Tehran, Iran, Tehran |

| Trans Boost | ترانس بوست | Electricity | Electrical transformer station (230 66 20 kV) in the Salameh, Hama area | ---- |

| B.T.S Company | بي تي سي | Import and export, and commercial brokerage | No information | ------ |

| Nestlé Iran P.J.S. Co. | شركة نستله | Food industries | Supply of milk to Syria for the time being | 6th Floor, No.3, Aftab Intersection, Khoddami St., Vanak Sq., Tehran, Iran |

Recruiting Local Partners (Iran vs. Russia)

Iran and Russia have been competing over the reconstruction of Syria and the potentially lucrative investment opportunities that come with it because both countries hope to recoup some of their outputs from years of supporting the Assad regime and also because both hope to maintain their influence in the post-war era. Both Tehran and Moscow are therefore striving to win over major players in the Syrian political and economic spheres whom they hope to rely on to facilitate their business deals and ensure their respective interests. Consequently, both countries have established economic councils to oversee their ventures and to organize relations with their respective Syrian partners.

The following descriptions of the Syrian-Russian and Syrian-Iranian business councils cover their structures, the total number of members, the most prominent players, and the companies affiliated with their members.

The Syrian-Russian Business Council

The Syrian-Russian Business Council (SRBC) includes 101 Syrian businessmen and a number of Russian counterparts. It is divided into seven committees covering the main sectors of the economy:

- Engineering

- Oil and gas

- Trade

- Communications

- Tourism

- Industry

- Transportation

The Syrian membership of the SRBC includes many influential names, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Members of the Syrian-Russian Business Council

| Notable Names | Total Number of Businessmen |

| Samir Hasan (Chairman, SRBC) | 101 |

| Jamal al-Din Qanabrian (Deputy Chairman, SRBC) | |

| Mohammed Abu al-Huda al-Lahham, (Secretary, SRBC) | |

| Fares al-Shehabi (Businessman) | |

| Mehran Khunda (Businessman) | |

| Bashar Nahad Makhlouf (Businessman) |

Of these figures, three are particularly prominent:

- Jamal al-Din Qanabrian has served as a member of the Consultative Council of Syria’s Council of Ministers since 2017 (the Council presents proposals and consultations to the government on economic and legislative affairs). He is also a member of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

- Samir Hassan, the chairman of the Syrian-Russian Business Council, is a partner in Sham Holding Company, which is owned by Rami Makhlouf.

- Mohammed Abu al-Huda al-Lahham, also a member of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce, is believed to have strong ties with Dhul-Himma Shalish, the powerful Syrian construction mogul and cousin and personal guard of Hafiz al-Assad.

The SRBC also employs a number of Syrian businessmen of Russian nationality, most notably George Hassouani, who was formerly involved in oil and gas deals with ISIS.

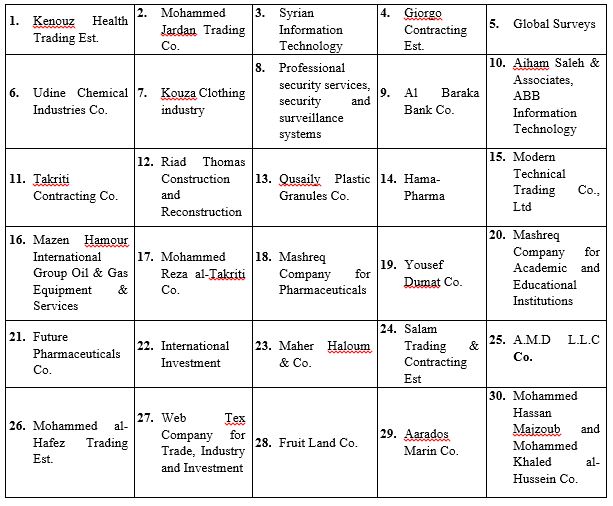

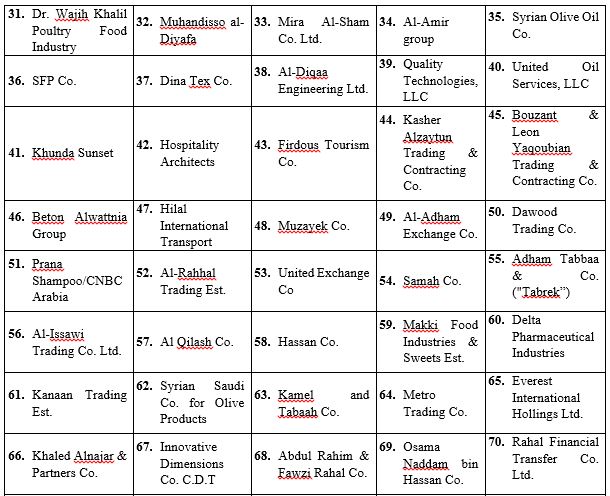

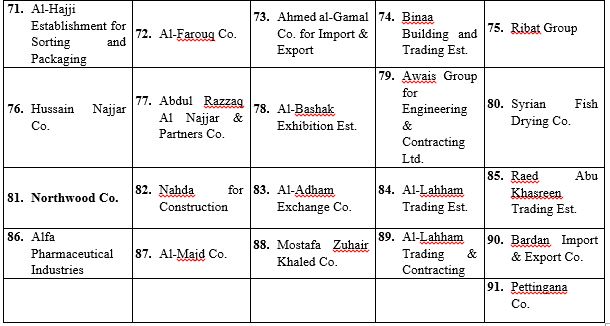

The number of Syrian companies included in the Syrian-Russian Business Council is estimated at 91. These companies are involved in import and export, general trade, textiles, clothing, petrochemicals, energy, and, in a small number of cases, private security operations (see Table 3).

Table 3: Companies in the SRBC

The Syrian-Iranian Business Council

By comparison, Iran has had less success with its business council venture than Russia. The Syrian-Iranian Business Council (SIBC) was established in March 2008, and was initially led by Hassan Jawad. It was reconstituted in 2014 with nine members, as shown below in Table 4.

Table 4: Members of the SIBC

| Notable Names | Total Number of Businessmen |

| Samer al-Asaad (President, SIBC) | b |

| Iyad Mohammed (Treasurer, SIBC) | |

| Mazen Hamour (Businessman) | |

| Osama Mustafa (Businessman) | |

| Hassan Zaidou (Businessman) | |

| Khaled al-Mahameed (Businessman) | |

| Abdul Rahim Rahal (Businessman) | |

| Mazen al-Tarazi (Businessman) | |

| Bashar Kiwan(Businessman) |

Some of these figures have significant economic influence:

- Mazen al-Tarazi is a prominent businessman with investments in the tourism sector as well as in real estate (including the project to redevelop Marota City in western Damascus). He has founded a number of companies in Syria, Kuwait, Jordan and elsewhere that offer services in oil well maintenance, advertising, publishing, paper trading, and general contracting. He also owns a number of newspapers, including Al-Hadaf Weekly Classified in Kuwait, Al-Ghad in Jordan, and Al-Waseet in Jordan.

- Iyad Mohammed is the Head of the Agricultural Section of the Syrian Exporters' Union.

- Osama Mustafa is a member of the People's Assembly, where he represents Rural Damascus Governorate. He served as Chairman of the regime’s Rural Damascus Chamber of Commerce between 2015-2018.

The number of companies owned by Syrian businessmen who are members of the SIBC board is estimated at 10 (see Table 5).

Table 5: Companies Owned by SIBC Members

|

Abdul Rahim & Fawzi Rahal Co. |

Al-Sharq Bank |

| Al-Shameal Oil Services Co. |

National Aviation, LLC |

| Rahal Money Transfer Co. |

Ebdaa Development & Investment Co. |

|

Mazen Hamour International Group |

Development Co. for Oil Services |

|

Dagher & Kiwan General Trading Co. |

Concord al-Sham International Investment Co. |

Because of the relatively small number of Syrian members of the SIBC, Iran is making additional efforts to woe Syrian businessmen. According to private sources, Syrian businessmen are seeking contracts with Iranian companies in return for being granted a share of the value of the contract. Table 6 shows key Syrian figures engaged with Iran.

Table 6: Syrian Businessmen Engaged with Iran

| Name | Position | Name | Position |

|

1.Faisal Talal Saif |

Head of the Suweida Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

2.Mohamed Majd al-Din Dabbagh |

Head of the Aleppo Chamber of Commerce |

|

3.Jihad Ismail |

Head of the Quneitra Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

4.Abdul Nasser Sheikh al-Fotouh |

Head of the Homs Chamber of Commerce |

|

5.Tarif al-Akhras |

Head of the Deir Ezzor Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

6.Osama Mostafa |

Head of the Rural Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

|

7.Adeeb al-Ashqar |

Merchant from the Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

8.Kamal al-Assad |

Head of Latakia Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

9.Albert Shawy |

Merchant |

10.Hamza Kassab Bashi |

Head of Hama Chamber of Commerce |

|

11.Amal Rihawi |

Director of International Relations at the Commercial Bank of Syria |

12.Mohammed Khair Shekhmous |

Head of the Hasaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

13.Elias Thomas |

Merchant |

14.Wahib Kamel Mari |

Head of the Tartous Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

15. |

Merchant |

16.Qassem al-Maslama |

Head of the Daraa Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

17.Saeb Nahas |

Merchant |

18.Aws Ali |

Merchant |

|

19.Ghassan Qallaa |

Head of the Federation of Chambers of Commerce |

20.Iyad Abboud |

General Manager of MOD |

|

21.Louay Haidari |

Merchant |

22.Ayman Shamma |

Merchant |

|

23.Mohamed Hamsho |

Secretary-General of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

24.Bassel al-Hamwi |

Merchant |

|

25.Mohamed Sawah |

Head of the Syrian Exporters Union |

26.Khaled Sukar |

Merchant |

|

27.Mohamed Keshto |

Head of the Union of Agricultural Chambers |

28.Sami Sophie |

Director of the Latakia Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

29.Marwa al-Itouni |

Head of Syrian Businesswomen |

30.Salman al-Ahmad |

Union of Syrian Agricultural Chambers |

|

31.Mustafa Alwais |

Rami Makhlouf 's partner |

32.Samir Shami |

Syrian Exporters Union |

|

33.Nahed Mortadi |

Merchant |

34.Gamal Abdel Karim |

Merchant |

|

35.Nidal Hanah |

Merchant |

36.Zuhair Qazwini |

Merchant |

|

37.George Murad |

Merchant |

38.Mohammed Ali Darwish |

Merchant |

|

39.Ghassan al-Shallah |

Merchant |

40.Nasouh Sairawan |

Merchant |

|

41.Mousan Nahas |

Merchant |

42.Anwar al-Shammout |

Owner of Sham Wings Co. |

|

43.Mounir Bitar |

Merchant |

44.Bashar al-Nouri |

Merchant |

|

45.Abdullah Natur |

Merchant |

46.Sawsan al-Halabi |

Director of a construction company |

|

47.Tony Bender |

Merchant |

48.Manaf al-Ayashi |

Foodco for Food Industries |

|

49.Maysan Dahman |

Merchant |

50.Khaled al-Tahawi |

Merchant |

|

51.Samer Alwan |

Blue Planet Energy Co. |

52.Saied Hamidi |

Oil and gas sector |

|

53.Roba Minqar |

Clothing industry |

54.Randa Sheikh |

Clothing industry |

|

55.Harout Dker-Mangi |

Merchant |

56.Alya Minqar |

Merchant |

Iran’s Role in Key Sectors

Iran seeks to obtain lucrative investment opportunities in different sectors of the Syrian economy, whether through tenders or monopolies. The main sectors in which Iran is trying to get full access are: agriculture, tourism, industry, reconstruction, and private security.

Agriculture

- Iran’s ability to match Russia’s investments in the Syrian agricultural sector has been significantly limited by the international sanctions imposed upon it. Since 2013 Iran has extended Syria two credit lines with the total value of USD 4.6 billion, aimed mostly at agriculture. Here is a list of Iranian investments in the sector:

- Supply of wheat since 2015 through the Safir Nour Jannat company"سفیر نور جنت".

- An agreement with the Syrian government to establish a joint company to export surplus Syrian agricultural products.

- An investment of USD 47 million for the second phase of implementation of the Iranian credit line to establish a plant to produce animal food, vaccines, and poultry products.

- A contract to build five mills in Syria at a cost of US 82 million in the provinces of Suweida and Daraa.

- A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Syrian General Organization of Sugar (Sugar Corporation) to establish a sugar mill and a sugar refinery in Salha in Hama in 2018.

- A 2018 MOU between the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Agriculture and the Iranian companies Nero and ITM for the import and distribution of 3,000 tractors.

Tourism

The tourism sector is considered one of the most vital sectors in the Syrian economy: it constituted a 14.4 percent share of Syria’s GDP in 2011 (US 64 billion). It has of course been heavily affected by the war, and tourism revenues decreased from SYP 297 billion (around USD 577 million) in 2010 to SYP 17 billion (around USD 33 million) in 2015, while tourism infrastructure suffered a loss of nearly SYP 14 billion (around USD 27 million) over that same period.

Tehran’s investment in Syria’s the tourism sector has been mostly in religious tourism. For instance, the Syrian Minister of Tourism signed a MOU with the Iranian Hajj Organization in 2015 to bring Iranians and others into Syria for religious tours. There are now estimated to be 225,000 religious tourists from Iran, Iraq, and the Gulf countries visiting Syria each year, and they bring in around SYP two billion (around USD 3.9 million) in revenue.

Industry

The industrial sector contributed 19 percent of Syria’s GDP in 2011, and has suffered losses estimated at USD 100 billion during the war. Iran has several industrial facilities in Syria. These are concentrated in the automobile sector, where they include the Syrian-Iranian International Motor Company and Siamco. Iran has also invested in the glass industry in Adra industrial city. The Iranian Saipa group announced a growth in sales of 11 percent in 2017 in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Azerbaijan. Car sales in Syria reached a significant level: although it was a third of 2018 sales in Iraq so far, 50,000 cars were sold in Syria last year.

Iran has tried to obtain contracts from the Syrian government in the industrial sector, and a number of MOUs have been signed. They include:

- A 2017 MOU between the Iranian company Bihin Ghostar Persian and General Organization for Engineering Industries to rehabilitate several companies: General Company for Metallic Industries–Barada (located in al-Sabinahis a town in southern Syria, administratively part of the Rural Damascus Governorate), SYRONICS (located in Damascus) and the battery factory in Aleppo.

- A 2017 MOU between the Syrian Cement and Building Materials Company in Hama and the Yasna Trading Company of Iran for the supply of spare parts.

In 2018, the Syrian-Iranian Business Council submitted a proposal for the participation of Iranian companies in the rehabilitation of Syria’s public industrial sector. In addition, the Iranian Ministry of Industry has expressed a wish to establish a cement production company in Aleppo as part of the second phase of implementation of the Iranian credit line.

Reconstruction and Infrastructure

The construction sector contributed 4.2 percent of Syria’s GDP in 2011 and then suffered a losses of USD 27 billion over the next six years. Syrian infrastructure has taken a similarly heavy hit as a result of the conflict, with losses valued at around at USD 33 billion, including over three million destroyed houses or housing units.

Iran’s interests in reconstruction—as with tourism—have a religious tinge and are mainly focused on the areas around sacred Shi’a shrines. For instance, Iran has been asking the Syrian regime for large concessions in Daraya, the old city of Damascus, Sayida Zainab, and Aleppo. Thus far Iran has mostly relied on Syrian intermediaries to purchase real estate, businessmen such as Bashar Kiwan, Mazen al-Tarazi, Mohammad Jamul, Saeb Nahas, Muhammad Abdul Sattar Sayyid, Daas Daas, Firas Jahm, Nawaf al-Bashir, and Mohammad al-Masha'li. Tehran has also relied on Syrian associations such as Jaafari, Jihad al-Binaa, the al-Bayt Authority, and “the Committee for the Reconstruction of the Holy Shrines" to expand and acquire new land in or near the holy sites in Damascus, Deir Ezzor, and Aleppo.

Sanctions against Syria and their Effect on Iran

The ongoing conflict in Syria has prompted international outcry and condemnation, as well as a long list of "red lines" and sanctions. The sanctions currently in place against Syria include an oil embargo, restrictions on certain investments, a freeze of the Syrian central bank's assets within the European Union, and export restrictions on equipment and technology that might be used for repression of Syrian civilians.

The problem with the sanctions on Syria is that they are ill suited to address the situation, in which sanctions are unlikely to work due to the ongoing war. The EU took significant steps very early in the Syrian conflict, essentially deploying its entire sanctions toolbox in less than one year, in contrast to its more common step-by-step sanctions approach. After a few years, the EU realized that this approach was rushed and ineffective and was forced to backtrack on some measures. This learning process showed the EU that an arms embargo is not necessarily the best first way to address a conflict situation.

Appendix

Syrian Companies Affiliated with Iran

| Name | Arabic Name | Main Activity | Agreement |

|

Abdul Rahim & Fawzi Rahal Co. |

شركة عبد الرحيم وفوزي رحال | معمل مواد بناء، تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير | حماة/طيبة الإمام، سوريا. |

| Ebdaa Development & Investment Co. | شركة إبداع للتطوير والاستثمار | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير | ريف دمشق |

|

Development Co. for Oil Services |

شركة التنمية لخدمات النفط | الخدمات النفطية | ------ |

| Obeidi for Construction & Trade | شركة عبيدي وشريكه للتجارة والمقاولات | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، المقاولات | فندق الداما روز بدمشق |

| Talaqqi Company | شركة تلاقي | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، مستحضرات التجميل | دمشق، كفرسوسة، عقار رقم 2463/ 87 |

| Nagam al-Hayat Company | شركة نغم الحياة | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، الخدمات الاستشارية | ريف دمشق، يلدا/ دف الشوك/ العقار رقم 507 |

| IBS for Security Services | ---- | --- | --- |

| Al-Hares for Security Services | شركة الحارس للخدمات الأمنية | خدمات الأمن والحماية الشخصية | دمشق |

| Mobivida L.L.C | شركة موبي فيدا | تجارة الأجهزة الإلكترونية، الهواتف المحمولة والإكسسوار، وتطوير خدمات الهواتف والإنترنت | دمشق |

| Al-Mazhor Company for Construction | شركة المظهور التجارية | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، المقاولات | دير الزور |

| Al Najjar & Zain Travel & Tourism Company | شركة النجار وزين" للسياحة والسفر | السياحة الدينية | نبل، مقابل مستوصف نبل عبارة الضرير / محافظة حلب |

Top Syrian Businessmen Affiliated with Iran

| Under EU Sanctions? | Under U.S. Sanctions? | Visited Abu Dahbi(UAE) in Jan 2019? | Main Position | Closeness of Relationship with Iran | Name in Arabic | Name |

| - | Yes | Yes | Secretary-General of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | High | محمد حمشو | Mohammad Hamsho |