Analyzing Iranian-Orchestrated Attacks on U.S. Bases in Syria and Iraq Post Gaza War

Introduction

The landscape of Middle Eastern conflict underwent a notable evolution in the aftermath of the Gaza War, with the Islamic Resistance in Iraq (IRI) emerging as a significant player in the matrix of Iranian-backed military operations. This report scrutinizes the pattern of IRI-initiated strikes on U.S. installations in Syria and Iraq and evaluates the corresponding U.S. military responses within the framework of the broader geopolitical contest that unfolded post the Gaza War.

The data compiled within this document have been meticulously sourced from the following authoritative resources:

1. Official Statements and Bulletins: Data was sourced directly from the Islamic Resistance in Iraq's official Telegram channels, associated Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) factions, formal press releases from the United States, and attack chronologies developed by Dr. Hamid Hamed, a recognized expert on IRGC and PMU activities in the region(1).

2. Strikes Specifics: Detailed strike coordination’s were obtained by the author of the report using ArcGIS.

3. Report Visual: Map, Charts, Data Tables, were created by the author of the report using ArcGis, Power Pi, and Adobe Illustrator.

The Emergence of the Islamic Resistance in Iraq: Coordination and Operations

The term “Islamic Resistance in Iraq” first came to prominence following the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, initially serving as an umbrella term for various Sunni armed factions known for their production of visual media and official statements. This collective identity waned as Shiite militant groups, backed by Iran, gained dominance. On October 21, 2023, the “Islamic Resistance in Iraq” reemerged in the spotlight when armed factions under this banner executed missile and drone strikes on U.S. military installations in Syria and Iraq. These attacks were a direct response to the Israeli offensive in the Gaza Strip in October 2023, which received U.S. support.

Unlike its initial formation in 2003, the reconstituted Islamic Resistance in Iraq, also referred to as Al-Muqawama al-Islamiyah fi al-Iraq, has evolved into a formidable coalition of militias with deep ties to Iran. Operating actively within Iraq and extending its influence into Syria, this alliance has become a pivotal force in the regional geopolitical arena. It challenges U.S. interests and presence through a sophisticated network of operations, employing military tactics to assert its influence and achieve its objectives across the Middle East(2). During the October 2023 conflict between Israel and Hamas, the Islamic Resistance in Iraq demonstrated its strategic capabilities and intentions by launching coordinated strikes against U.S.-aligned targets. These operations underscored the coalition's role as a significant actor in the broader regional conflict, capable of conducting complex military actions across borders. The group's involvement in these strikes aligns with Iran's regional goals and its commitment to countering U.S. military influence and policies in the Middle East.

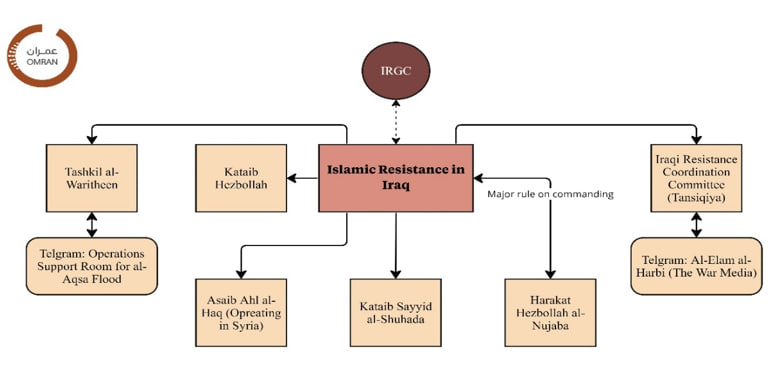

Figure (1): Islamic Resistance in Iraq Structure at the Time of Formation

The Islamic Resistance in Iraq's command structure showcases an advanced level of organization and coordination, significantly influenced by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF), the IRGC-QF plays a crucial role in orchestrating the activities of the coalition, bringing together various Iraqi militia groups under a unified command for strategic purposes (3).

The strategic operations carried out by the coalition during this period were characterized by their high degree of coordination and sophistication, highlighting the group's ability to mobilize and execute military strategies effectively. These actions were not only aimed at challenging U.S. interests in the region but also demonstrated the coalition's capacity for significant military engagement. The ability of the coalition to extend its operations to Syria further exemplifies its broad reach and the transnational nature of its objectives.

The adoption of the “Islamic Resistance in Iraq” as a collective term is particularly noteworthy, echoing the nomenclature historically used by Iran-backed Iraqi armed groups. This branding strategy not only strengthens the collective identity of these militias but also acts as a unifying label that embodies their shared ethos of resistance. Prominent groups within the coalition, such as Kataib Hezbollah, Asaib Ahl al-Haq, and Kataib Sayyid al-Shuhada, have refrained from claiming separate operations within their usual areas of influence. This suggests a strong sense of unity within the coalition, emphasizing its role as a comprehensive representation of Iran-backed resistance efforts in Iraq (4).

Overview of Attacks Against U.S. Bases in Syria and Iraq by the IRI

Between October 18, 2023, and February 28, 2024, a total of /190/ attacks were reported against U.S. military bases in Syria and Iraq. The Islamic Resistance in Iraq (IRI) claimed responsibility for the majority of these incidents, showcasing a blend of conventional and innovative tactics in their operations. The group's arsenal featured medium-range missiles (al-Aqsa 1), drones (Qasef-2K/Shahed 101), and suicide drones, reflecting a strategic evolution and experimentation in their approach to combat. While the bulk of these assaults took place in Iraq and Syria, a handful were also recorded in Jordan, targeting vital strategic assets such as airbases, oil fields, and critical locations housing U.S. forces. These sites, heavily fortified with advanced defense mechanisms and artillery, underscore the strategic significance of the targets chosen by the IRI.

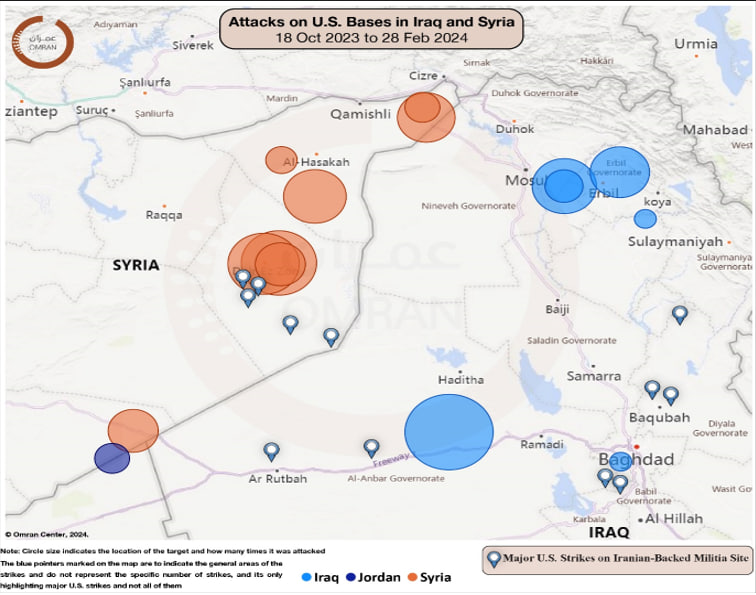

Map (1): Locations of the Attacks on U.S. Bases in Syria, Iraq, and Jordan – 18 Oct 2023 to 28 Feb 2024

Post-Gaza War Attacks on U.S. Bases

In the aftermath of the Gaza conflict, the IRI launched its initial assault on October 18, 2023, executing simultaneous strikes on the Ain Asad Airbase and the Harir US Base in Iraq. The Ain Asad Airbase emerged as a focal point, enduring /37/ documented attacks. The Harir US Base and Erbil Airport also ranked high on the IRI's target list, suffering /15/ and /5/ attacks, respectively. The IRI's tactics were marked by diversity and sophistication, employing Iranian-manufactured drones, artillery, and long-range missiles to execute their strategic objectives(5-6-7) Shifting focus to Syria, the al-Omar Oil Field and Conoco Gas Field were subjected to a combined total of /49/ attack. This strategic focus on targeting facilities near the border between the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and areas controlled by the Syrian regime “Area of Iran high presence and influence” in Deir Ezzor highlights the IRI's strategic priorities. Military bases such as the Shadadi US Base and the al-Tanf US Base were also significantly targeted, receiving /17/ and /10/ attacks, respectively, further emphasizing the strategic pattern of the IRI's operations across the region. A detailed breakdown of the targets can be found in the Appendix.

This period of heightened activity by the IRI against U.S. bases in Syria and Iraq not only demonstrates the group's operational capabilities and strategic intent but also highlights the evolving landscape of military engagement in the region, with implications for both regional stability and international security dynamics.

| WK No. | Year | Start Date | End Date | Total Attacks by Week | %Attacks by Week | Total Attacks by Month | %Attacks by Month | Attacks in Syria | Attacks in Jordan | Attacks in Iraq |

| WK42 | 2023 | 18-10-23 | 24-10-23 | 13 | 7% | 28 | 15% | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| WK43 | 2023 | 25-10-23 | 31-10-23 | 15 | 8% | 10 | 0 | 5 | ||

| WK44 | 2023 | 01-11-23 | 07-11-23 | 20 | 11% | 51 | 27% | 14 | 0 | 6 |

| WK45 | 2023 | 08-11-23 | 14-11-23 | 15 | 8% | 11 | 0 | 4 | ||

| WK46 | 2023 | 15-11-23 | 21-11-23 | 9 | 5% | 3 | 0 | 6 | ||

| WK47 | 2023 | 22-11-23 | 28-11-23 | 7 | 4% | 2 | 0 | 5 | ||

| WK48 | 2023 | 29-11-23 | 05-12-23 | 4 | 2% | 48 | 24% | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| WK49 | 2023 | 06-12-23 | 12-12-23 | 16 | 9% | 9 | 0 | 7 | ||

| WK50 | 2023 | 13-12-23 | 19-12-23 | 9 | 5% | 7 | 1 | 1 | ||

| WK51 | 2023 | 20-12-23 | 26-12-23 | 4 | 2% | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| WK52 | 2023 | 27-12-23 | 02-01-24 | 15 | 8% | 8 | 0 | 7 | ||

| WK01 | 2024 | 03-01-24 | 09-01-24 | 10 | 5% | 47 | 26% | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| WK02 | 2024 | 10-01-24 | 16-01-24 | 12 | 6% | 6 | 0 | 6 | ||

| WK03 | 2024 | 17-01-24 | 23-01-24 | 8 | 4% | 4 | 0 | 4 | ||

| WK04 | 2024 | 24-01-24 | 30-01-24 | 17 | 9% | 8 | 1 | 8 | ||

| WK05 | 2024 | 31-01-24 | 05-02-24 | 4 | 2% | 16 | 8% | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| WK06 | 2024 | 06-02-24 | 12-02-24 | 6 | 3% | 6 | 0 | 0 | ||

| WK07 | 2024 | 13-02-24 | 19-02-24 | 3 | 2% | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| WK08 | 2024 | 20-02-24 | 28-02-24 | 3 | 2% | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 190 | 109 | 4 | 77 | |||||||

| 57% | 2% | 41% |

Table (1): IRI Attacks Breakdown 18 October 2023 to 28 February 2024

Strategic Dynamics and Retaliatory Patterns in U.S.-IRI Conflict: A Timeline Analysis

Late October to Mid-November 2023: Retaliatory Dynamics in Deir Ezzor

The initiation of U.S. strikes on October 27, followed by further actions on October 30 and November 9, 2023, marks a period of increased military activity, notably during weeks 42 to 45. This escalation aligns with the visit of the U.S. Secretary of State on November 5, suggesting a deliberate pattern of engagement and possibly an effort to demonstrate U.S. determination. The temporal correlation between these U.S. military operations and the surge in attacks indicates a retaliatory dynamic, highlighting the conflict's reactive nature, where U.S. actions prompt immediate countermeasures by opposing factions.

December 2023 to January 2024: Escalation Following U.S. Airstrikes

A NOTICEABLE INCREASE IN ATTACKS IN WEEK 49 AND CONTINUING INTO EARLY JANUARY 2024 CORRELATES WITH U.S. AIRSTRIKES ON DECEMBER 23 AND SUBSEQUENT JANUARY OPERATIONS TARGETING NUJABA ATTACK CELLS AND THEIR LEADERS. THIS PATTERN SUGGESTS A CYCLE OF REPRISAL FOLLOWING U.S. MILITARY INTERVENTIONS. THE FLUCTUATING ATTACK RATES IN RESPONSE TO U.S. ACTIONS REVEAL A CONTINUOUS LOOP OF ACTION AND RETALIATION, EMPHASIZING THE DIFFICULTY OF SECURING A LASTING DE-ESCALATION THROUGH MILITARY MEANS ALONE.

Late January 2024: The Rukban (Tower 22) Attack and Its Aftermath

THE SIGNIFICANT UPTICK IN ATTACKS DURING WEEK 04, CULMINATING IN THE RUKBAN ATTACK ON JANUARY 28 THAT RESULTED IN SEVERAL U.S. CASUALTIES, FOLLOWED BY KATAIB HEZBOLLAH'S SUSPENSION OF ATTACKS ON JANUARY 30, REPRESENTS A CRITICAL JUNCTURE. THIS PAUSE IN HOSTILITIES MAY HAVE CONTRIBUTED TO A DECREASE IN ATTACKS AGAINST U.S. BASES, AS OBSERVED IN THE SUBSEQUENT REDUCTION IN WEEK 05. THIS SERIES OF EVENTS UNDERSCORES THE INTRICATE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DIRECT CONFRONTATIONS WITH CASUALTIES AND THE STRATEGIC DECISIONS BY MILITANT GROUPS TO TEMPORARILY CEASE OPERATIONS, EITHER FOR REASSESSMENT OR AS A TACTICAL PAUSE IN ANTICIPATION OF THE U.S. RESPONSE TO THE (TOWER 22) INCIDENT.

Early February 2024: U.S. Airstrikes and Strategic Implications

In early February 2024, the United States launched airstrikes on over /90/ locations in Syria and Iraq, targeting the operational capabilities of Iran-backed militias. Among the key figures targeted were two commanders from Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba, including the military operations director, Abu Baqr al-Saeedi. These actions are part of a broader U.S. strategy aimed at countering Iranian influence and militia activities in the Middle East, reflecting the intricate balance of military power, strategic interests, and regional dynamics. The U.S. justified these strikes as self-defense measures to protect its forces from Iranian-backed group attacks, emphasizing a focus on terrorist entities supported by the IRGC and avoiding Iraqi state forces to minimize collateral damage and prevent an escalation with Iraqi authorities.

Late February 2024: Strategic Pause by Militant Groups

A significant development occurred when Akram al-Kaabi, the General Secretary of al-Nujaba within the Popular Mobilization Forces and the Islamic Resistance in Iraq, announced a temporary cessation of hostilities against U.S. bases by his group and other IRI factions. This pause, described as a tactical repositioning rather than an end to hostilities, indicates a strategic recalibration by the militias in response to U.S. military pressure. This move suggests a nuanced interplay of tactics, signaling, and strategic adjustments by both U.S. forces and Iranian-backed groups, highlighting the ongoing complexity and unpredictability of the regional security landscape (8).

Pattern of the Attacks: IRI's Leading Role in Targeting U.S. Bases

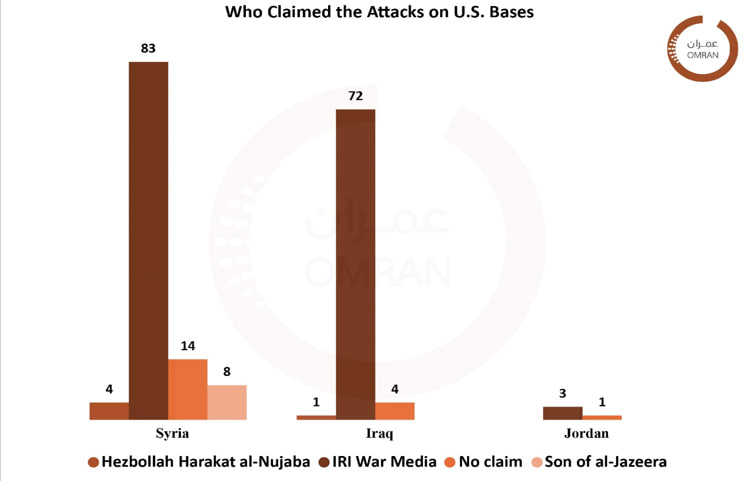

Between October 18, 2023, and February 28, 2024, U.S. military bases located in Syria, Iraq, and Jordan were subjected to a total of /190/ attack. The IRI has been identified as the primary perpetrator, claiming responsibility for /158/ of these incidents. This represents approximately 83% of the total attacks, highlighting the IRI's dominant operational presence and its aggressive posture towards U.S. forces in the region. Additionally, Hezbollah al-Nujaba has acknowledged their role in /5/ specific events, which accounts for nearly 3% of the overall attacks. These targeted operations by Hezbollah al-Nujaba were reportedly in direct retaliation to U.S. strikes on their leadership and facilities.

The emergence of the “Son of Al-Jazeera” armed group, responsible for /8/ attacks or about 4% of the total during this period, marks a notable development. Although their involvement is relatively minor, these attacks were distinctly aimed at SDF personnel at U.S. bases or checkpoints within Deir Ezzor. Insights from sources in Deir Ezzor suggest that these incidents are linked to the ongoing tensions between Arab tribes and SDF/Asayish forces in the region. The volatile security environment, further destabilized by the IRI's actions, has led to several significant assaults, particularly near the Al-Omar oil field and Conoco gas field in Deir Ezzor, resulting in numerous SDF casualties.(9) However, /19/ incidents, accounting for 10% of the total, remain unclaimed. The absence of attribution for these attacks might reflect a strategic choice by certain groups to maintain operational secrecy or a deliberate decision to avoid recognition to prevent potential retaliatory or political consequences (10).

Chart (1): Analyzing Responsibility for Attacks on U.S. Bases - 18 October 2023 to 28 February 2024

Overall Implication and Strategic Assessment

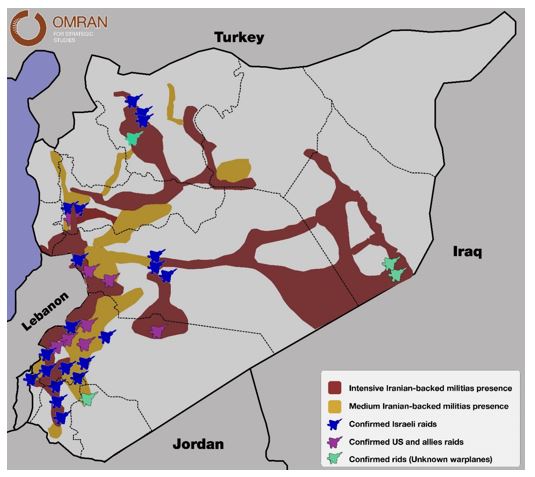

The intricate geopolitical landscape of the Middle East, marked by the Islamic Resistance in Iraq's (IRI) calculated strikes on U.S. interests, showcases a nuanced Iranian strategy of employing proxy groups to extend its sphere of influence across the region. From October 2023 to January 2024, the IRI's assertive military operations have underscored its pivotal role within Iran's broader strategy of exerting pressure across the Middle East. This approach mirrors the tactics of other Iranian-backed militias in southern Syria against northern Israel, Hezbollah's activities in the same area, and the Houthi campaigns in Yemen and against Israeli targets. The synchronized efforts of these proxies, under Tehran's direction, represent a multifaceted campaign aimed at bolstering Iran's bargaining position against the United States. The uniformity of these operations across various fronts highlights a coherent Iranian strategy designed to project power and gain leverage(11).

In response, the United States has adopted a containment strategy aimed at mitigating IRI attacks and curbing broader Iranian influence, favoring management of regional tensions over escalation. This measured military response reflects a strategic choice to maintain the status quo while avoiding the onset of a larger conflict that neither the U.S. nor Iran desires. (12) The U.S. strategy extends beyond direct military engagements to include collaborative efforts with regional allies. From October 7, 2023, to March 5, 2024, Israel executed /41/ strikes on Iran-affiliated targets, significantly undermining their operational capabilities. These operations resulted in the destruction of several key locations and the assassination of /15/ high-ranking IRGC commanders, with the IRGC's War-Media unit confirming the deaths of /10/ of these figures. Moreover, Jordan's initiatives against armed groups in southern Syria, alongside joint UK-U.S. operations targeting the Houthis in Yemen, play a crucial role in the overarching U.S. strategy to counter Iranian influence in the region. These collaborative actions underscore a comprehensive approach to mitigating the challenges posed by Iran and its proxies, emphasizing the importance of international partnerships in addressing regional security concerns (13-14).

This multilateral approach underscores a concerted effort to challenge Iranian interests from multiple angles, thereby bolstering the effectiveness of U.S. containment strategies. Through both independent and coordinated actions, a comprehensive U.S.-led initiative aims to limit Iranian expansion without precipitating a wider conflict. In this complex environment, both Iran and the U.S. leverage their respective alliances and capabilities to exert influence and secure advantages, setting the stage for a potential return to diplomatic negotiations. Both nations, recognizing the risks of escalating a sustained pressure campaign into a more significant conflict, seem inclined towards dialogue. This strategic perspective acknowledges that while pressure tactics can be maintained temporarily, they do not serve the long-term interests of either party and pose the risk of sparking a broader confrontation that both sides are eager to avoid.

Conclusion

In summary, the activities of the Islamic Resistance in Iraq (IRI) from October 2023 to February 2024 mark a critical juncture in the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East, characterized by a nuanced blend of military actions, strategic positioning, and diplomatic efforts. The IRI's bold initiatives, including numerous attacks on U.S. interests and its synergy with Iran's regional goals, underscore its pivotal role in the complex geopolitical tapestry of the Middle East. These events not only pose challenges to the U.S.'s strategic interests in the region but also mirror the larger power struggle between the U.S. and Iran, a contest played out through proxy groups and tactical military engagements.

The IRI's advanced organizational structure, strategic operations, and unified branding as a resistance movement reflect a deliberate strategy of military and political engagement. This strategy is emblematic of Iran's broader aim to utilize proxy forces as tools of regional dominance, seeking to assert influence and gain strategic advantages over the United States. The sequence of assaults followed by U.S. and allied counteractions highlights a persistent cycle of action and reaction, emphasizing the difficulties in securing enduring peace and stability in the region solely through military means.

This era of heightened conflict and strategic interaction between the IRI, the U.S., and their allies accentuates the need for a comprehensive approach that goes beyond conventional military responses. Such an approach must integrate diplomatic initiatives, political solutions, and regional collaborations to adeptly address the multifaceted challenges facing the Middle East. The primary objective should be to de-escalate tensions, avert a wider conflict, and strive for a lasting peace that tackles the root causes of the ongoing cycle of violence and retribution. The events spanning late 2023 to early 2024 serve as a vivid reminder of the delicate power equilibrium in the region and the paramount importance of strategic diplomacy in reducing the risk of further escalations and ensuring long-term stability.

([1]) Islamic Resistance in Iraq and other affiliations accounts on Telegram Platform. (To better understand how the present any positive/negative developments for their followers)

([2]) The Islamic Resistance in Iraq...a coalition of armed groups to support the “Al-Aqsa Flood”, 5 February 2024. Al-Jazzera https://shorturl.at/gmqL8

([3]) The Islamic Resistance in Iraq, October 17, 2023. Hamdi Malik, Michael Knights, https://bit.ly/3wFASrj.

([4]) Profile: Al-Warithuun, September 13, 2022 (Updated on October 2023), The Washington Institute, Michael Knights, Hamdi Malik, Crispin Smith, https://bit.ly/3P5obfV.

([5]) Signs of Iranian Coordination in Iraqi Base Attacks and Messaging, The Washington Institute, Post October 17, 2023. Analyzes the coordination behind attacks on US bases in Iraq, emphasizing Iranian involvement.

([6]) The "Islamic Resistance" in Iraq: We attacked 3 American bases in Iraq and Syria with missiles and drones, 24 February 2024 https://shorturl.at/txDMY

([7])Syria & Yemen, The Iran Primer, United States Institute of Peace, October 18, 2023. Insights into drone and rocket attacks by Pro-Iranian militias in Iraq and Syria.

([8]) A movement affiliated with the “Iraqi Resistance”: We continue to target Zionist sites, February 25, 2024, Al-Quds https://shorturl.at/nKX14

([9]) Anti-U.S. Attacks Linked to the Sons of Jazira and Euphrates Movement, The Washington Institute, October 27, 2023. Hamdi Malik, Michael Knights https://bit.ly/3P7xoEt.

([10]) Iran Update, October 23, 2023, Institute for the Study of War, October 23, 2023. Discusses Iranian activities and positions in relation to the ongoing conflict.

Iran Update, October 24, 2023, Institute for the Study of War, October 24, 2023. Analysis of Iran's information operations and their i

mpact on the conflict.

Iran Update, November 18, 2023, Institute for the Study of War, November 18, 2023. Briefs on recent threats and attacks by Iranian-backed militias against US forces.

([11]) “The calm before the storm and surprises are coming.” Al-Nujaba escalates its rhetoric against the American forces in Iraq, 26 February 2024. Sputnik https://shorturl.at/xLVY6

([12]) Assessment of Security Threats to U.S. Military Installations in the Middle East Post-Gaza Conflict, U.S. Department of Defense, https://www.defense.gov

([13]) U.S. launches strikes in Iraq, Syria, nearly 40 reported killed, February 04, 2024. Reuters https://bit.ly/3wE3v8d

([14]) US Strikes Stoking Tensions with Iraq, February 06, 2024. Jeff Seldin, Voice Of America, https://bit.ly/49AcqGq.

Significant Economic Cooperation Between The Syrian Regime and Iran During 2018-19

Executive Summary

Iran, a major ally and enabler of the Syrian regime, is increasingly engaged in competition over access to the Syrian economy now that there are new opportunities for lucrative reconstruction contracts. This report sheds light on the economic role played by Iran in Syria through its local representatives and Iranian businessmen. It also explores the (limited) impact of the European Union and U.S. Treasury sanctions on Iran's economic instruments in Syria.

Introduction

Iran has invested heavily in the protection of the Syrian regime and the recovery of its territories. Iran’s main objectives in Syria have been to secure a land bridge between its territory and Lebanon, and to maintain a friendly regime in Damascus. Much of Iran’s investment has been military, as it has financed, trained, and equipped tens of thousands of Shi’a militants in the Syrian conflict. But Iran has also made major financial and economic interventions in Syria: it has extended two credit lines worth a total of USD 4.6 billion, provided most of the country's needs for refined oil products, and sent many tons of commodities and non-lethal equipment, notwithstanding the international sanctions imposed on the regime. In exchange for its commitment to ensuring Assad’s survival, Tehran has expected and demanded large concessions in terms of access to the Syrian economy, especially in the energy, trade, and telecommunications sectors.

Key Iranian Companies

Iran has provided crucial economic assistance to the Assad regime in order to prevent its fall and to ensure that it can meet its fuel needs. In return, Iran demanded access to significant investment opportunities in key sectors of the Syrian economy, notably: state property, transportation, telecommunications, energy, construction, agriculture, and food security.

Since 2013, the Iranians have aided Assad through two main channels. First, it extended two lines of credit for the import of fuel and other commodities, with a cumulative value of over USD 4.6 billion. In order to position itself strategically as the lynchpin of the Syrian economy, Iran restricted the benefactors and implementers of these credit lines to its own national companies. It can thus continue to provide the regime with a lifeline in terms of goods and energy supplies, but in return it can control key parts of the Syrian economy.

The following list includes major Iranian companies that have announced a return to business-as-usual in Syria. Each brief overview gives a description of the company’s involvement in Syria, followed by basic information about the company.

Khatam al-Anbia Construction Base

Has demonstrated an interest in carrying out reconstruction work on Syria infrastructure.

Khatam al-Anbia Construction Base is involved in construction projects for Iran's ballistic missile and nuclear programs. It is listed by the UN as an entity of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), with a role “in Iran's proliferation-sensitive nuclear activities and the development of nuclear weapon delivery systems” (Annex to U.N. Security Council Resolution 1929, June 9, 2010). The company is under the command of Brigadier General Ebadollah Abdollahi.

Khatam al-Anbia conducts civil engineering activities, including road and dam construction and the manufacture of pipelines to transport water, oil, and gas. It is also involved in mining operations, agriculture, and telecommunications. Its main clients include the Ministry of Energy, Ministry of Oil, Ministry of Roads and Transportation, and Ministry of Defense.

Since the company’s founding in 1990 it has designed and implemented approximately 2,500 projects at the provincial and national levels in Iran. It currently works with 5,000 implementing partners from the private sector. An IRGC official recently revealed that a total of 170,000 people currently work on Khatam al-Anbia’s projects and that in the past 2.5 years it has recruited 3,700 graduates from Iran’s leading universities.

Company officials for Khatam al-Anbia include IRGC General Rostam Qasemi and Deputy Commander Parviz Fatah. Other personnel reportedly include Abolqasem Mozafari-Shams and Ershad Niya.

MAPNA Group

- Supplying five generating sets for gas and diesel operations (credit line)

- Construction of a 450 MW power plant in Latakia (credit line)

- Implementation of two steam and gas turbines for the power plant supplying the city of Baniyas (credit line)

- Rehabilitation of the first and fifth units at the Aleppo power plant (credit line).

MAPNA is a group of Iranian companies that build and develop thermal power plants, as well as oil and gas installations. The group is also involved in railway transportation, manufacturing gas and steam turbines, electrical generators, turbine blades, boilers, gas compressors, locomotives, and other related products. The Iran Power Plant Projects Management Company (MAPNA) was founded in 1993 by the Iranian Ministry of Energy. Since 2012, the group has been led by Abbas Aliabadi, former Iranian Deputy Minister of Energy in Electricity and Energy Affairs.

In 2015, MAPNA sealed a USD 2.5 billion contract, Iran’s largest engineering deal to date, to supply Iranian technical and engineering services for the construction of a power station in Basra in southern Iraq.

Mobile Telecommunication Company of Iran (MCI)

A contract to build Syria’s third mobile network (suspended).

MCI is a subsidiary of the Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI), which is partially owned by the IRGC. MCI brings in approximately 70 percent of TCI’s profits. MCI provides mobile services for over 1,000 cities in Iran and has approximately 66 million Iranian subscribers. It provides roaming services through partner operators in more than 112 countries.

Iranian Companies Active in Syria in 2019

Table 1: List of all Iranian companies with ongoing contracts in Syria - 2019

| Name | Arabic Name | Main Activity | Agreement | Headquarters Address |

| Safir Noor Jannat | سفير نور جنات | Food industries, detergents, and electronics | An old MOU dating back to 2015 to supply Syria with flour | No. 8, Mohamadzadeh st., Fat-h- highway 4Km. Tehran |

| Behin Gostar Parsian | بهين كستر بارسيان | Food industries | No information | Unit 5. No 14. Shahid Gomnam Street. Fatemi Sq. Tehran |

|

Peimann Khotoot Gostar Company جزء من مجموعة PARSIAN GROUP |

بيهين غوستار بارسيان | Electrical power, electronics, and technology | 2017 MOU with the batteries companies in Aleppo, the General Company for Metallurgical Industries in Barada, and Sironix, to carry out electricity projects in several locations in Syria. | Tehran Province, Tehran, District 22, No: 5, Kaj Blvd, 14947 35511, Iran |

| Feridolin Industrial & Manufacturing Company | شركة فريدولين | Electrical appliances | No information | ----- |

| Tadjhizate Madaress Iran. T.M.I. Co. | ---- | Decor and furnishings | No information | No. 198, Dr. Beheshti St., After Sohrevardi Cross Rd., 157783611, Tehran, Iran, Tehran |

| Trans Boost | ترانس بوست | Electricity | Electrical transformer station (230 66 20 kV) in the Salameh, Hama area | ---- |

| B.T.S Company | بي تي سي | Import and export, and commercial brokerage | No information | ------ |

| Nestlé Iran P.J.S. Co. | شركة نستله | Food industries | Supply of milk to Syria for the time being | 6th Floor, No.3, Aftab Intersection, Khoddami St., Vanak Sq., Tehran, Iran |

Recruiting Local Partners (Iran vs. Russia)

Iran and Russia have been competing over the reconstruction of Syria and the potentially lucrative investment opportunities that come with it because both countries hope to recoup some of their outputs from years of supporting the Assad regime and also because both hope to maintain their influence in the post-war era. Both Tehran and Moscow are therefore striving to win over major players in the Syrian political and economic spheres whom they hope to rely on to facilitate their business deals and ensure their respective interests. Consequently, both countries have established economic councils to oversee their ventures and to organize relations with their respective Syrian partners.

The following descriptions of the Syrian-Russian and Syrian-Iranian business councils cover their structures, the total number of members, the most prominent players, and the companies affiliated with their members.

The Syrian-Russian Business Council

The Syrian-Russian Business Council (SRBC) includes 101 Syrian businessmen and a number of Russian counterparts. It is divided into seven committees covering the main sectors of the economy:

- Engineering

- Oil and gas

- Trade

- Communications

- Tourism

- Industry

- Transportation

The Syrian membership of the SRBC includes many influential names, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Members of the Syrian-Russian Business Council

| Notable Names | Total Number of Businessmen |

| Samir Hasan (Chairman, SRBC) | 101 |

| Jamal al-Din Qanabrian (Deputy Chairman, SRBC) | |

| Mohammed Abu al-Huda al-Lahham, (Secretary, SRBC) | |

| Fares al-Shehabi (Businessman) | |

| Mehran Khunda (Businessman) | |

| Bashar Nahad Makhlouf (Businessman) |

Of these figures, three are particularly prominent:

- Jamal al-Din Qanabrian has served as a member of the Consultative Council of Syria’s Council of Ministers since 2017 (the Council presents proposals and consultations to the government on economic and legislative affairs). He is also a member of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

- Samir Hassan, the chairman of the Syrian-Russian Business Council, is a partner in Sham Holding Company, which is owned by Rami Makhlouf.

- Mohammed Abu al-Huda al-Lahham, also a member of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce, is believed to have strong ties with Dhul-Himma Shalish, the powerful Syrian construction mogul and cousin and personal guard of Hafiz al-Assad.

The SRBC also employs a number of Syrian businessmen of Russian nationality, most notably George Hassouani, who was formerly involved in oil and gas deals with ISIS.

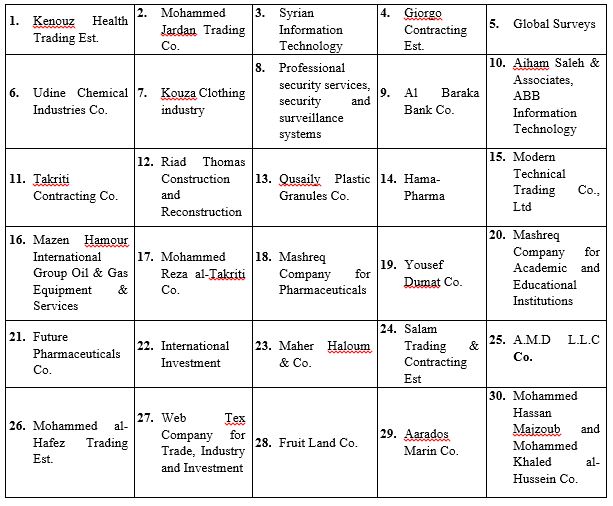

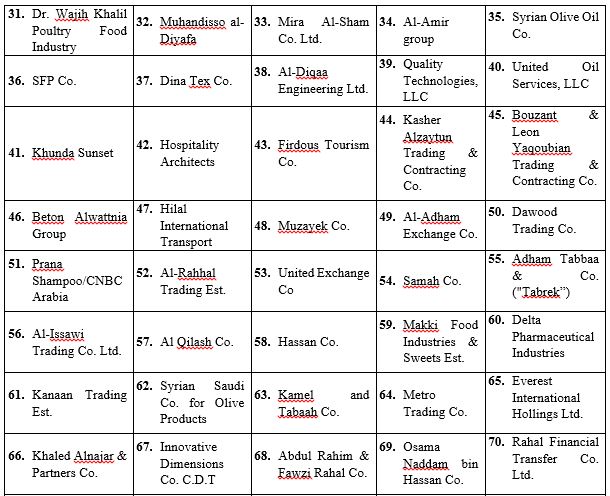

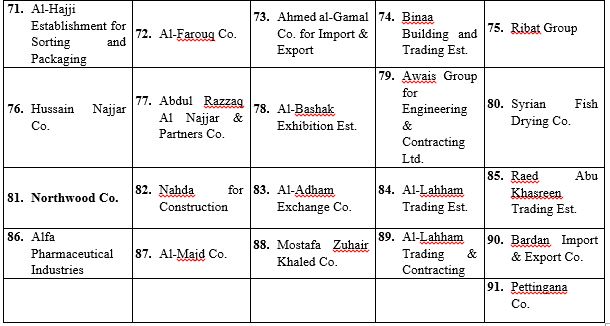

The number of Syrian companies included in the Syrian-Russian Business Council is estimated at 91. These companies are involved in import and export, general trade, textiles, clothing, petrochemicals, energy, and, in a small number of cases, private security operations (see Table 3).

Table 3: Companies in the SRBC

The Syrian-Iranian Business Council

By comparison, Iran has had less success with its business council venture than Russia. The Syrian-Iranian Business Council (SIBC) was established in March 2008, and was initially led by Hassan Jawad. It was reconstituted in 2014 with nine members, as shown below in Table 4.

Table 4: Members of the SIBC

| Notable Names | Total Number of Businessmen |

| Samer al-Asaad (President, SIBC) | b |

| Iyad Mohammed (Treasurer, SIBC) | |

| Mazen Hamour (Businessman) | |

| Osama Mustafa (Businessman) | |

| Hassan Zaidou (Businessman) | |

| Khaled al-Mahameed (Businessman) | |

| Abdul Rahim Rahal (Businessman) | |

| Mazen al-Tarazi (Businessman) | |

| Bashar Kiwan(Businessman) |

Some of these figures have significant economic influence:

- Mazen al-Tarazi is a prominent businessman with investments in the tourism sector as well as in real estate (including the project to redevelop Marota City in western Damascus). He has founded a number of companies in Syria, Kuwait, Jordan and elsewhere that offer services in oil well maintenance, advertising, publishing, paper trading, and general contracting. He also owns a number of newspapers, including Al-Hadaf Weekly Classified in Kuwait, Al-Ghad in Jordan, and Al-Waseet in Jordan.

- Iyad Mohammed is the Head of the Agricultural Section of the Syrian Exporters' Union.

- Osama Mustafa is a member of the People's Assembly, where he represents Rural Damascus Governorate. He served as Chairman of the regime’s Rural Damascus Chamber of Commerce between 2015-2018.

The number of companies owned by Syrian businessmen who are members of the SIBC board is estimated at 10 (see Table 5).

Table 5: Companies Owned by SIBC Members

|

Abdul Rahim & Fawzi Rahal Co. |

Al-Sharq Bank |

| Al-Shameal Oil Services Co. |

National Aviation, LLC |

| Rahal Money Transfer Co. |

Ebdaa Development & Investment Co. |

|

Mazen Hamour International Group |

Development Co. for Oil Services |

|

Dagher & Kiwan General Trading Co. |

Concord al-Sham International Investment Co. |

Because of the relatively small number of Syrian members of the SIBC, Iran is making additional efforts to woe Syrian businessmen. According to private sources, Syrian businessmen are seeking contracts with Iranian companies in return for being granted a share of the value of the contract. Table 6 shows key Syrian figures engaged with Iran.

Table 6: Syrian Businessmen Engaged with Iran

| Name | Position | Name | Position |

|

1.Faisal Talal Saif |

Head of the Suweida Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

2.Mohamed Majd al-Din Dabbagh |

Head of the Aleppo Chamber of Commerce |

|

3.Jihad Ismail |

Head of the Quneitra Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

4.Abdul Nasser Sheikh al-Fotouh |

Head of the Homs Chamber of Commerce |

|

5.Tarif al-Akhras |

Head of the Deir Ezzor Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

6.Osama Mostafa |

Head of the Rural Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

|

7.Adeeb al-Ashqar |

Merchant from the Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

8.Kamal al-Assad |

Head of Latakia Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

9.Albert Shawy |

Merchant |

10.Hamza Kassab Bashi |

Head of Hama Chamber of Commerce |

|

11.Amal Rihawi |

Director of International Relations at the Commercial Bank of Syria |

12.Mohammed Khair Shekhmous |

Head of the Hasaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

13.Elias Thomas |

Merchant |

14.Wahib Kamel Mari |

Head of the Tartous Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

15. |

Merchant |

16.Qassem al-Maslama |

Head of the Daraa Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

17.Saeb Nahas |

Merchant |

18.Aws Ali |

Merchant |

|

19.Ghassan Qallaa |

Head of the Federation of Chambers of Commerce |

20.Iyad Abboud |

General Manager of MOD |

|

21.Louay Haidari |

Merchant |

22.Ayman Shamma |

Merchant |

|

23.Mohamed Hamsho |

Secretary-General of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce |

24.Bassel al-Hamwi |

Merchant |

|

25.Mohamed Sawah |

Head of the Syrian Exporters Union |

26.Khaled Sukar |

Merchant |

|

27.Mohamed Keshto |

Head of the Union of Agricultural Chambers |

28.Sami Sophie |

Director of the Latakia Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

|

29.Marwa al-Itouni |

Head of Syrian Businesswomen |

30.Salman al-Ahmad |

Union of Syrian Agricultural Chambers |

|

31.Mustafa Alwais |

Rami Makhlouf 's partner |

32.Samir Shami |

Syrian Exporters Union |

|

33.Nahed Mortadi |

Merchant |

34.Gamal Abdel Karim |

Merchant |

|

35.Nidal Hanah |

Merchant |

36.Zuhair Qazwini |

Merchant |

|

37.George Murad |

Merchant |

38.Mohammed Ali Darwish |

Merchant |

|

39.Ghassan al-Shallah |

Merchant |

40.Nasouh Sairawan |

Merchant |

|

41.Mousan Nahas |

Merchant |

42.Anwar al-Shammout |

Owner of Sham Wings Co. |

|

43.Mounir Bitar |

Merchant |

44.Bashar al-Nouri |

Merchant |

|

45.Abdullah Natur |

Merchant |

46.Sawsan al-Halabi |

Director of a construction company |

|

47.Tony Bender |

Merchant |

48.Manaf al-Ayashi |

Foodco for Food Industries |

|

49.Maysan Dahman |

Merchant |

50.Khaled al-Tahawi |

Merchant |

|

51.Samer Alwan |

Blue Planet Energy Co. |

52.Saied Hamidi |

Oil and gas sector |

|

53.Roba Minqar |

Clothing industry |

54.Randa Sheikh |

Clothing industry |

|

55.Harout Dker-Mangi |

Merchant |

56.Alya Minqar |

Merchant |

Iran’s Role in Key Sectors

Iran seeks to obtain lucrative investment opportunities in different sectors of the Syrian economy, whether through tenders or monopolies. The main sectors in which Iran is trying to get full access are: agriculture, tourism, industry, reconstruction, and private security.

Agriculture

- Iran’s ability to match Russia’s investments in the Syrian agricultural sector has been significantly limited by the international sanctions imposed upon it. Since 2013 Iran has extended Syria two credit lines with the total value of USD 4.6 billion, aimed mostly at agriculture. Here is a list of Iranian investments in the sector:

- Supply of wheat since 2015 through the Safir Nour Jannat company"سفیر نور جنت".

- An agreement with the Syrian government to establish a joint company to export surplus Syrian agricultural products.

- An investment of USD 47 million for the second phase of implementation of the Iranian credit line to establish a plant to produce animal food, vaccines, and poultry products.

- A contract to build five mills in Syria at a cost of US 82 million in the provinces of Suweida and Daraa.

- A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Syrian General Organization of Sugar (Sugar Corporation) to establish a sugar mill and a sugar refinery in Salha in Hama in 2018.

- A 2018 MOU between the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Agriculture and the Iranian companies Nero and ITM for the import and distribution of 3,000 tractors.

Tourism

The tourism sector is considered one of the most vital sectors in the Syrian economy: it constituted a 14.4 percent share of Syria’s GDP in 2011 (US 64 billion). It has of course been heavily affected by the war, and tourism revenues decreased from SYP 297 billion (around USD 577 million) in 2010 to SYP 17 billion (around USD 33 million) in 2015, while tourism infrastructure suffered a loss of nearly SYP 14 billion (around USD 27 million) over that same period.

Tehran’s investment in Syria’s the tourism sector has been mostly in religious tourism. For instance, the Syrian Minister of Tourism signed a MOU with the Iranian Hajj Organization in 2015 to bring Iranians and others into Syria for religious tours. There are now estimated to be 225,000 religious tourists from Iran, Iraq, and the Gulf countries visiting Syria each year, and they bring in around SYP two billion (around USD 3.9 million) in revenue.

Industry

The industrial sector contributed 19 percent of Syria’s GDP in 2011, and has suffered losses estimated at USD 100 billion during the war. Iran has several industrial facilities in Syria. These are concentrated in the automobile sector, where they include the Syrian-Iranian International Motor Company and Siamco. Iran has also invested in the glass industry in Adra industrial city. The Iranian Saipa group announced a growth in sales of 11 percent in 2017 in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Azerbaijan. Car sales in Syria reached a significant level: although it was a third of 2018 sales in Iraq so far, 50,000 cars were sold in Syria last year.

Iran has tried to obtain contracts from the Syrian government in the industrial sector, and a number of MOUs have been signed. They include:

- A 2017 MOU between the Iranian company Bihin Ghostar Persian and General Organization for Engineering Industries to rehabilitate several companies: General Company for Metallic Industries–Barada (located in al-Sabinahis a town in southern Syria, administratively part of the Rural Damascus Governorate), SYRONICS (located in Damascus) and the battery factory in Aleppo.

- A 2017 MOU between the Syrian Cement and Building Materials Company in Hama and the Yasna Trading Company of Iran for the supply of spare parts.

In 2018, the Syrian-Iranian Business Council submitted a proposal for the participation of Iranian companies in the rehabilitation of Syria’s public industrial sector. In addition, the Iranian Ministry of Industry has expressed a wish to establish a cement production company in Aleppo as part of the second phase of implementation of the Iranian credit line.

Reconstruction and Infrastructure

The construction sector contributed 4.2 percent of Syria’s GDP in 2011 and then suffered a losses of USD 27 billion over the next six years. Syrian infrastructure has taken a similarly heavy hit as a result of the conflict, with losses valued at around at USD 33 billion, including over three million destroyed houses or housing units.

Iran’s interests in reconstruction—as with tourism—have a religious tinge and are mainly focused on the areas around sacred Shi’a shrines. For instance, Iran has been asking the Syrian regime for large concessions in Daraya, the old city of Damascus, Sayida Zainab, and Aleppo. Thus far Iran has mostly relied on Syrian intermediaries to purchase real estate, businessmen such as Bashar Kiwan, Mazen al-Tarazi, Mohammad Jamul, Saeb Nahas, Muhammad Abdul Sattar Sayyid, Daas Daas, Firas Jahm, Nawaf al-Bashir, and Mohammad al-Masha'li. Tehran has also relied on Syrian associations such as Jaafari, Jihad al-Binaa, the al-Bayt Authority, and “the Committee for the Reconstruction of the Holy Shrines" to expand and acquire new land in or near the holy sites in Damascus, Deir Ezzor, and Aleppo.

Sanctions against Syria and their Effect on Iran

The ongoing conflict in Syria has prompted international outcry and condemnation, as well as a long list of "red lines" and sanctions. The sanctions currently in place against Syria include an oil embargo, restrictions on certain investments, a freeze of the Syrian central bank's assets within the European Union, and export restrictions on equipment and technology that might be used for repression of Syrian civilians.

The problem with the sanctions on Syria is that they are ill suited to address the situation, in which sanctions are unlikely to work due to the ongoing war. The EU took significant steps very early in the Syrian conflict, essentially deploying its entire sanctions toolbox in less than one year, in contrast to its more common step-by-step sanctions approach. After a few years, the EU realized that this approach was rushed and ineffective and was forced to backtrack on some measures. This learning process showed the EU that an arms embargo is not necessarily the best first way to address a conflict situation.

Appendix

Syrian Companies Affiliated with Iran

| Name | Arabic Name | Main Activity | Agreement |

|

Abdul Rahim & Fawzi Rahal Co. |

شركة عبد الرحيم وفوزي رحال | معمل مواد بناء، تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير | حماة/طيبة الإمام، سوريا. |

| Ebdaa Development & Investment Co. | شركة إبداع للتطوير والاستثمار | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير | ريف دمشق |

|

Development Co. for Oil Services |

شركة التنمية لخدمات النفط | الخدمات النفطية | ------ |

| Obeidi for Construction & Trade | شركة عبيدي وشريكه للتجارة والمقاولات | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، المقاولات | فندق الداما روز بدمشق |

| Talaqqi Company | شركة تلاقي | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، مستحضرات التجميل | دمشق، كفرسوسة، عقار رقم 2463/ 87 |

| Nagam al-Hayat Company | شركة نغم الحياة | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، الخدمات الاستشارية | ريف دمشق، يلدا/ دف الشوك/ العقار رقم 507 |

| IBS for Security Services | ---- | --- | --- |

| Al-Hares for Security Services | شركة الحارس للخدمات الأمنية | خدمات الأمن والحماية الشخصية | دمشق |

| Mobivida L.L.C | شركة موبي فيدا | تجارة الأجهزة الإلكترونية، الهواتف المحمولة والإكسسوار، وتطوير خدمات الهواتف والإنترنت | دمشق |

| Al-Mazhor Company for Construction | شركة المظهور التجارية | تجارة عامة، استيراد وتصدير، المقاولات | دير الزور |

| Al Najjar & Zain Travel & Tourism Company | شركة النجار وزين" للسياحة والسفر | السياحة الدينية | نبل، مقابل مستوصف نبل عبارة الضرير / محافظة حلب |

Top Syrian Businessmen Affiliated with Iran

| Under EU Sanctions? | Under U.S. Sanctions? | Visited Abu Dahbi(UAE) in Jan 2019? | Main Position | Closeness of Relationship with Iran | Name in Arabic | Name |

| - | Yes | Yes | Secretary-General of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | High | محمد حمشو | Mohammad Hamsho |

| - | - | - | Member of Syrian Parliament | High | حسين رجب | Hussein Ragheb |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | حسان زيدو | Hassan Zaidou |

| - | Yes | Yes | Member of Syrian Parliament | High | محمد خير | Muhammad Kheir Suriol |

| - | Yes | Yes | Member of Syrian Exporters Union | High | إياد محمد | Iyad Muhammad |

| - | Yes | Yes | Manager of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | High | فراس جيكلي | Firas Jijkli |

| - | - | - | Chairman of the Supreme Committee for Investors in the Free Zone | High | فهد درويش | Fahd Darwish |

| - | - | - | Syrian Ambassador to Iran | High | عدنان محمود | Adnan Mahmoud |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Medium | عامر خيتي | Amer Khiti |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | علاء الدين خير بيك | Alla Ed din Khair Bik |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Low | جورج مراد | George Murad |

| - | Businessman | Low | منير بيطار | Munir Bitar | ||

| Yes | Yes | - | Works in SDF-controlled area and has relationship with Samir al-Foz | High | محمد القاطرجي | Mohamed al-Qtrji |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | علي كامل | Ali Kamil |

| - | - | Yes | Al-Matin Group General Manager | Medium | لبيب إخوان | Labib Ikhwan |

| - | - | - | Businessman | High | سامر علوان | Samir Alwan |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Medium | ناهد مرتضى | Nahid Murtda |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Medium | مصان النحاس | Musan al-Nahas |

| - | - | Yes | Businessman | High | ربى منقار | Ruba Munqar |

| - | - | - | Businessman | Low | هاروت ديكرمنيجان | Harot Dikrmnjyan |

Iranian influence within the Regime Army.. 2017/18 strikes that targeted Iran in Syria

Introduction

Iran was present in Syria from the very beginning of the revolution and was a strong supporter of the Syrian regime, In addition to providing the regime with weapons, soldiers, advisors, money, and political support, Iran also brought in sectarian fighters from countries including Afghanistan, Iraq, and Lebanese to form militias and fight alongside the regime.

Today in 2019, Iran's role in Syria appears to be expanding even further. Iran’s strategy has entered a new phase in which it recruits Syrians loyal to the regime to fight under direct administration and command of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), relying on local defense forces and newly formed military brigades.

Iran’s Most Significant Influences in the Syrian Army

Local Defense Forces (LDF) and National Defense Forces (NDF): A Comparison

The National Defense Forces (NDF) was established in 2012 under the direct supervision of Iran to serve as an auxiliary militia force for the Syrian army. By the end of 2017, a similar group known as the Local Defense Forces (LDF) was established in Aleppo governorate, specifically in its eastern countryside. The LDF consisted of several small local militias operated directly under the supervision of Iran, but without any legal status in Syria. Iran established and supported the LDF and linked its structure to the structure of the Syrian army, avoiding the error that occurred when the NDF were established. Recently, LDF members have been able to resolve their legal status and join the Syrian army, but their time in the LDF is not counted as time in the army's service.

On 6 April 2017, a memorandum from the "Organization and Administration Division / Branch of Organization and Armament" was issued to the General Commander of the Army and the Armed Forces, Bashar al-Assad, in order to suggest ways to formalize the status of Syrians, both civilians and military, who have worked with the Iranian side throughout the crisis. President Bashar al-Assad signed that document, in agreement, in April 2017.([1])

The document was signed by the head of the "Organization Division" Maj. Gen. Adnan Mehrez Abdo, the Chairman of the General Staff of the Army and the Armed Forces, General Ali

Ayoub, the Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and the Minister of Defense, General Fahd Jassim al-Fereij.

According to the document, the committee examined the organization of these forces from the aspects of "organization, leadership, combat, and material guarantee, rights of the martyrs, wounded and disappeared, sorting out the affairs of those commissioned who have avoided obligatory and reserve service and deserters, and the civilians working with the Iranian side." It recommended the following proposals:

- First: To organize the military and civilian elements who are fighting with the Iranian side as part of the local defense brigades in the governorates. The document includes a table showing the numbers of personnel who dodged compulsory and reserve service, deserters, civilians, and their status by governorate. The total number of troops is 88,733.

- Second: To resolve the situations of military deserters and those wanted for the compulsory and reserve service, and to transfer and appoint them to the local defense brigades in the governorates. This should include those whose situations have already been settled and are already working with the Iranian side as part of the local defense regiments. The document lists the numbers of those individuals as 51,729.

- Third: To organize volunteer contracts for civilians working with the Iranian side in the armed forces for a period of two years, regardless of the conditions of volunteerism in force in the armed forces. The document lists the number of civilians working with the Iranian side as 37,400.

- Fourth: To resolve the situation of the 1,650 officers in the 69 Officers Course who are currently working with the Iranian side in the governorate of Aleppo.

- Fifth: The leadership of local defense regiments working with the Iranian side in the governorates should remain with the Iranians in coordination with the General Command of the Army and Armed Forces until the end of the crisis in Syria, or until a new resolution is issued.

- Sixth: To provide all types of military and civilian insurance for Syrians working with the Iranian side, after they are organized into the local defense regiments in the governorates, in coordination with the competent authorities.

- Seventh: The responsibility for guaranteeing the material rights of the martyrs, wounded, and missing persons who have been working with the Iranians since the beginning of the conflict should fall on the Iranian side.

- Eighth: To issue instructions to regulate the executive instructions for military and civilian personnel working with the Iranian side, after organizing them into the local defense regiments in the governorates.

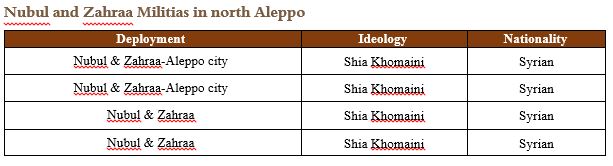

The following tables lay out the most prominent combat groups that were part of the LDF at the time of its establishment. The groups named below, in addition to several additional formations that participated in the battle of the southern Aleppo countryside in early 2018, include an estimated 45,000 fighters in total:

The LDF also spearheaded the battles against ISIS in Deir Ezzor and the southern Raqqa countryside. These are now the military,security, and administrative forces controlling the area stretching from the southern countryside of Deir Ezzor, passing through southern Raqqah, all the way to the eastern countryside of Aleppo and the Aleppo city. The following are the most important formations that joined the LDF in early 2018:

| Nationality | Deployment | Name |

| Syrian | Aleppo | Doshka Brigade |

| Syrian | Aleppo | Al-Safira Brigade |

| Syrian | Hama | Al-Berri Brigade |

| Syrian | Hama | Al-Hikma Brigade |

| Syrian | Aleppo | Al-Nayrab Regiment |

| Syrian-Iraqi-Lebanese | Aleppo - Raqqah | Islamic Resistance in Syria |

| Syrian | Homs | Al-Rida Forces |

| Syrian | Homs | Al-Radwan Forces |

| Syrian | Idlib | Suqur al-Dhaher Forces |

| Syrian | Aleppo | Khan al-Asal Eagles |

| Syrian-Iraqi | Deir Ezzor | Force 313 |

| Syrian | Hama | Al-Ghadab Christian Forces |

| Syrian | Tadmur(Palmyra) | Imam Zayb al-Abdeen Brigade |

| Syrian | Lattakia Countryside | Al-Qirsh Group |

Brigade 313: The IRGC’s New Military Formation

Iran has continued its efforts to expand into southern Syria despite international agreements aimed at limiting its role in the region. In doing so, Iran is violating the Hamburg agreement between Russia and the United States, which required Iranian troops and affiliated militias to stay at least 35 kilometers away from the Syrian-Jordanian border. ([2])

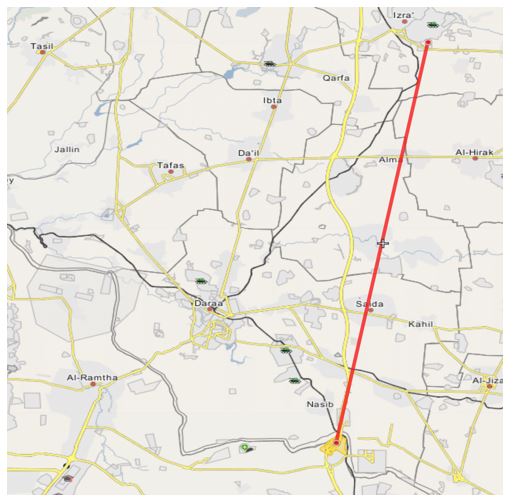

In November 2017, the IRGC established a special military body on the southern fronts of the Syrian army, called "Brigade 313." That same year, the brigade opened a recruitment center in the city of Izra'a in Daraa governorate. Through this center, Brigade 313 attracted more than 200 young Syrians from Daraa, most of whom were young people who reconciled their status with the regime in 2017. New members of Brigade 313 receive an identity card bearing the emblem of the IRGC, which ensures their ability to pass through the regime force checkpoints. Within two weeks of joining Brigade 313, recruits are enrolled in training camps in Izra'a and Sheikh Meskin.

Brigade 313’s headquarters is located about 30 kilometers from the border with Jordan and about 45 kilometers from Israel. For this reason, the brigade's location poses a direct threat to the agreement between Washington and Moscow.

Iran's efforts to recruit local elements and integrate other militias with these bodies ramped up in anticipation of international efforts to deport Iranian-backed militias containing foreign elements, mostly from Afghanistan, Lebanon, and Iraq.

Major Israel and U.S. attacks on Iranian forces and affiliated militias in Syria

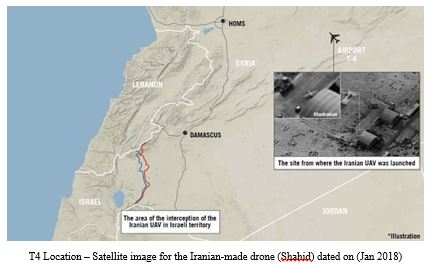

10 February 2018 – Israeli attacks

- An Israeli Apache helicopter intercepted unmanned Iranian reconnaissance aircraft that entered the Golan Heights and sirens were heard in the area of Besan, Israel.

- Following the drone infiltration, Israeli warplanes attacked Iranian targets at T4 (Tiyas) airbase in Syria.

- One of the Israeli warplanes crashed near the Galilee in northern Israel after it was hit by a missile launched from Regiment 16 in Syria, which is controlled by Iran.

Following the crash of the Israeli warplane, the Israeli Air Force responded by targeting several, locations near the administrative border between Damascus governorate and the southern governorates of Daraa and Quneitra. Specifically, Israel targeted areas where the Iranian-backed Brigade 313 forces andLebanese Hezbollah forces are stationed in the town of Al-Dimas on the Damascus-Beirut road near the Syrian-Lebanese border.

The Israeli Defense Force (IDF) media announced that seven locations were successfully destroyed (three Syrian air defense batteries and four targets belonging to Iran), and confirmed that Syrian regime anti-aircraft missiles capacity dropped to 50% after most of its locations were destroyed.

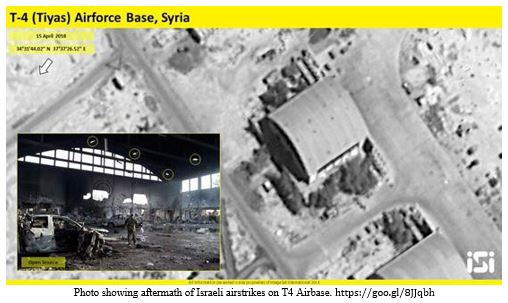

9 April 2018 – Israeli attacks

Israeli warplanes fired a number of missiles at the T4 (Tiyas) airbase from Lebanon’s airspace. Seven IRGC forces were announced dead following the attack.

Iranian locations that were targeted before, after, and during the April 2018 strikes by the U.S. and its allies

| 2018 Major hits before the US strike on Syria | |||||||

| Date | Province | Area | Location | Local Forces | International Forces | Attacker | Note |

| 10/2/2018 | Homs | Eastern Rural | Tayyas Airbase (T4) | Regime and Pro- Iran forces | IRGC and Hezbollah | Israel | Strike Destroyed: Iranian Drone - main control tower - military accommodation |

| 9/4/2018 | Homs | Eastern Rural | Tayyas Airbase (T4) | Regime and Pro- Iran forces | IRGC and Hezbollah | Israel | Strike Destroyed: Three warehouses - the death of 7 IRGC fighters |

| 2018 Major hits During the US strike on Syria | |||||||

| Date | Province | Area | Location | Local Forces | International Forces | Attacker | Note |

| 14/4/2018 | Damascus | The City | 41 Special forces HQ | No Forces | Hezbollah | Unknown | The strike is not mentioned in foreign or local media |

| 14/4/2018 | Homs | Qatyna Lake | Military Warehouse | No Forces | Hezbollah | Unknown | Hezbollah didn’t publish anything about this location |

Between 15 and 18 April 2018, after the U.S.-led attacks on Syria, two Iranian locations in Syria were reportedly targeted by unknown attacker: one in the Azzan Mountains in southern Aleppo and the other near al-Shiraat Airbase. There was no confirmation from the regime’s media regarding these attacks, only local sources confirmed seeing or hearing the explosions.

| Full list of All the Location targeted during the US hit (Confirmed or Not) | ||||

| Province | Location | Presence of IRGC | Presence of Pro-Iran | Strike Confirmation |

| Hama | Scientific Research in Misyaf | Yes | Yes | Not Confirmed |

| Homs | Hezbollah HQ North of al-Qusayr | No | Yes | Not Confirmed |

| Homs | Military Warehouse Near Qatyna lake | No | Yes | Confirmed |

| Damascus | Scientific Research in Barzeh | No | Yes | Confirmed |

| Damascus | Scientific Research in Jamraya | No | Yes | Confirmed |

| Damascus | Al-Dumyer Airbase | No | Yes | Not Confirmed |

| Damascus | Al-Kiswa Military Locations | Yes | Yes | Not Confirmed |

| Damascus | Brigade 105 | No | No | Confirmed |

| Damascus | Mazzeh Airbase | No | No | Confirmed |

| Damascus | 41 Special Forces HQ | No | Yes | Confirmed |

| Damascus | Rhayba Military Locations | No | Yes | Not Confirmed |

8 May 2018 -Israeli attacks

Israeli missiles struck the first Armored Division (Jabal Al-Mani) in al-Kiswa near the Syrian capital Damascus. The attack took place after an hour after U.S. President Donald Trump announced he was withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal. At least 13 fighters were killed in the attack; seven of them were members of the IRGC and other Iran-backed militias.

Hitham Abdul Rasol, IRGC commander and developer of "Fajr-3" Iranian missile defense system, visited two Iranian locations on the same day of the attack: one in al-Zabadani and the other at the Damascus International Airport. Both of these locations are likely to host "Fajr-3" systems.

10May 2018 – Israeli attacks

After Iranian forces fired 20 rockets at Israeli military positions in the Golan Heights at night on 9 May 2018, Israeli Air Force planes entered Syrian airspace to attack dozens of Iranian targets inside of Syria. The following table lists the major locations that were targeted:

| Province | Location | Coordinates | IRGC | Pro Iran Militias |

| Damascus | Western Ghouta (Tell Harboon) | 33°21'7"N 35°52'15"E | No | Yes |

| Quneitra | Khan Arnaba | 33°10'56"N 35°52'51"E | No | Yes |

| Quneitra | Khan Arnaba (Tell al-Qubu) | 33°12'12"N 35°53'3"E | No | Yes |

| Damascus | Kanakir (Brigade 121) | 33°16'46"N 36°4'51"E | Yes | No |

| Damascus | Al-Kiswa | 33°22'58"N 36°14'5"E | Yes | Yes |

| Damascus | Al-Kiswa (1st Armoured Division) | 33°21'6"N 36°17'39"E | Yes | Yes |

| Quneitra | Khan Arnaba (Tell al-Shaar) | 33°10'29"N 35°56'34"E | No | Yes |

| Daraa | Mahji (Air Defense Base) | 32°56'8"N 36°12'34"E | No | Yes |

| Daraa | Izraa (12th Armoured Brigade) | 32°51'29"N 36°16'23"E | No | Yes |

25December 2018 – Israeli attacks

On 25 December 2018, Israel launched a series of airstrikes against military targets in Damascus and its countryside, targeting military sites and weapons stores where pro-Iranian forces were deployed. These strikes were launched in two stages and are unique in terms of timing, targets, intensity, and messaging.

These Israeli attacks were the ninth of their kind in 2018. They were the second such strikes to take place after Russia's deployment of the S-300 air defense missile system and the first since Donald Trump announced the withdrawal of U.S. forces from eastern Syria. Israel’s 25 December strikes were notable because they indicated the return of coordination between Moscow and Tel Aviv in Syrian airspace in support of their common interests in the reduction of Iranian influence and potential expansion in Syria. They were also notable because they conveyed the clear message that Israel would continue its policy of striking Iranian forces and infrastructure in Syria despite the U.S. withdrawal. The intensity and length of the attacks may also indicate Israel's readiness for a future escalation against Iran in Syria and serve to push Russia and the U.S. to deal more seriously with the dilemma of expanding Iranian influence.

Israel sees the American withdrawal from Syria as an opportunity to intensify its pressure on Iran and test Iran’s reaction. If Iran responds aggressively to Israel’s intensification, it will lead to regional escalation and pressure the U.S. to adopt more punitive policies and measures against Iran, possibly delaying the U.S. withdrawal from Syria. It may also delay Iran's plans to expand in the eastern region of Syria to counter the growing Russian presence there. However, Iran may also choose to absorb these Israeli strikes and respond either on a small scale or not at all, in order to focus on filling the vacuum in the eastern region following the U.S. withdrawal. It will encourage Israel to launch more attacks against inside Syria during the transitional U.S. withdrawal period if it is actually completed, which is a likely scenario.

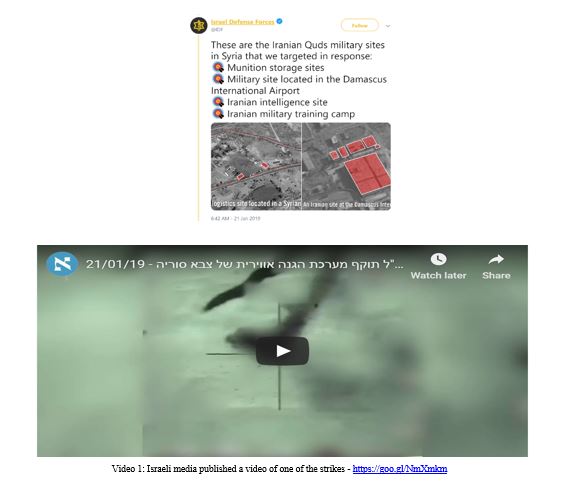

17 January 2019 – Israeli attacks

The Israeli Air Force struck some ten targets in Syria overnight from Sunday 20 January – Monday 21 January. The attack targets included arms warehouses at Damascus International Airport and other locations, and sites belonging to IRGC including an Iranian intelligence site and an Iranian training camp. The attacks were in response to a ground-to-ground missile that was fired at Israel from Syria a day earlier and intercepted.

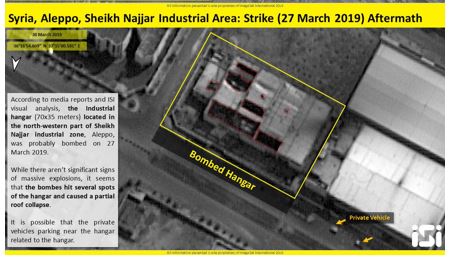

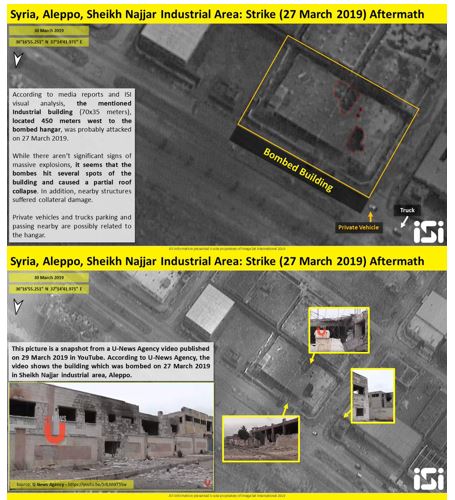

27 March 2019 – Israeli attacks

The Israeli air force launched airstrikes on the industrial zone in the northern city of Aleppo, causing damage only to materials as per the official pro-Regime news agency "SANA," while opposition sources said the strikes hit Iranian ammunitions stores and a military airport used by Iranian-backed militia's forces. ([3])

Inside sources confirmed that the Israeli airstrikes targeted two warehouses in the industrial area of Sheikh Najar. The warehouses contained light and medium ammunition, based on the type of ammunition that was heard in the blast after the airstrikes.

These warehouses are under the control of Iranian-backed militias, until now the identity of the militia, which was hit, is under investigation. However, according to previous information Badr Organization, Fatemiyoun, Hezbollah, and al-Nujbaa are based in this area.

The site of the airstrikes was locked down for seven hours then it was opened only for LDF forces and SANA, which published pictures of the site showing that the raid targeted an empty warehouse and only caused martial damage.

ISI published recent pictures of the location that was targeted, the pictures showed several damaged warehouse in the area of the airstrikes, and it's also visible that these airstrikes targeted specific locations and not a random hit in order to destroy empty buildings as per the official regime news agency statement.

Pro-Iranian accounts promote that the strike was in line with Turkey's desire to empty the towns of Nubl and Zahraa to form a Sunni belt, that's why the regime with the support of the Iranian took the decision to intensify the military presence to prevent any future Turkish military plan.

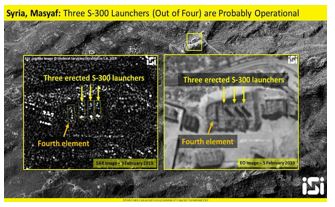

13 April 2019 – Israeli attacks

The Israeli Air Force launched airstrikes from Lebanese airspace on targets in the Syrian province of Hama. According to inside sources and Pro-Regime media, the target was a military location of IRGC and other Iranian-backed militias and the area is located between the research center and al-Talaa Camp.

In February 2019, ISI center published pictures showing the Russian S-300 surface-to-surface missile system based in Syria near the targeted area. This was the third strike in 2019 that explicitly targeted Iranian-backed militias.

The first one targeted Damascus International Airport, the second was on Aleppo airport and the industrial zone, while the latest, as we mentioned, it targeted Iranian-backed militias’ bases near the city of Masyaf in Hama province.

Conclusion

Since 2017, Iranian military sites in Syria have been continuously targeted by Israel, the U.S. and their allies. These attacks pushed Iran to find a way to protect its presence. Since 2018 Iran has been reintegrating its militias into military formations affiliated with the Syrian regime, which has led to reducing the intensity of the raids against them but did not prevent them.

In general, the raids on Iranian sites did not have a long-term impact on Iran's strategy and goals in the region. The areas under Iranian influence in Syria remain large with various levels of infiltration (military, security, social and economic). This Iranian infiltration and expansion strategy came as a precautionary measure if air strikes were to continue.

([1])Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi. Administrative Decisions on Local Defence Forces Personnel: Translation & Analysis. 3-5-2017. Link: https://goo.gl/ngXYKc

([2]) 2 The Russian-American "Hamburg Agreement" on Syria: Its Objectives and Implications, Arabs 48, 11-7-2017, https://goo.gl/hW4GAr

([3]) Location of the raid: http://wikimapia.org/m/#lat=36.2631&lon=37.255325&z=11&l=36&m=b