Early Economic Recovery in Opposition Controlled Areas between 2018 -2022

Introduction and Methodology

Early economic recovery aims to support local communities in returning to a stable and normal life, including preventing the community from returning to violence. The Early Recovery Report monitors projects implemented over a period of six months and is issued semi-annually, focusing on the main cities and towns in the "Euphrates Shield","Afrin" and Idlib governorate, which is witnessing remarkable economic activity, within 11 sectors which are: social services, transportation, electricity, water and sanitation, housing and construction, agriculture and livestock, finance, industry, trade, internal displacement, and communications.

The report relied on the official identifiers of local councils and organizations operating on Facebook and Telegram. The data was analyzed according to two levels, the first at the level of economic sectors, and the second by geographical level. Among the monitored areas in the countryside of Aleppo: Marea, A'zaz, al-Bab, Jarabulus, Akhtarin, Qabasin, Bza'a, Afrin, and Al Atarib. In Idlib Governorate: Idlib, Harem, Sarmada, Ma'arrat Misrin, Hazano, Salqin, Armanaz, Termanin, Atme, Al-Dana, Kah, Deir Hassan.

The report aims to analysis and understand the following:

- Monitor the dynamics of the activities and works carried out in the region, thus measuring the development of local economies, and comparing regions and sectors with each other.

- Exploring the ability of local and international actors to create a safe environment for living and working, and the ability of local councils to play a governance role and sign memoranda of understanding with companies and organizations that contribute to providing with the necessary projects.

Distribution of Projects According to Sectors

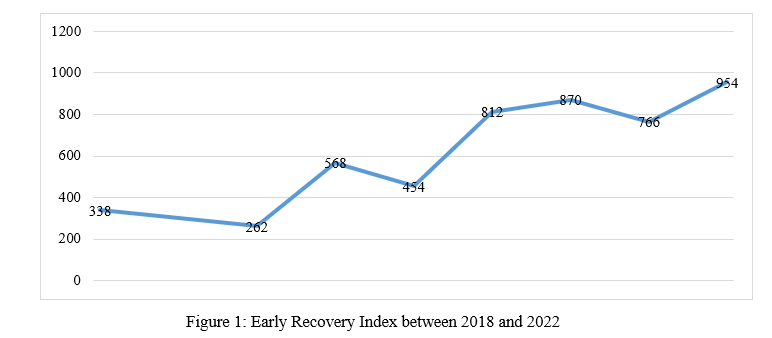

Overall, 5,024 projects were implemented in the countryside of Aleppo and Idlib between 2018 to 2022 through eleven economic sectors. The number of projects rose slowly with 338 projects in the second half of 2018 to 954 projects in the first half 2022 as shown in Figure No. (1) below.

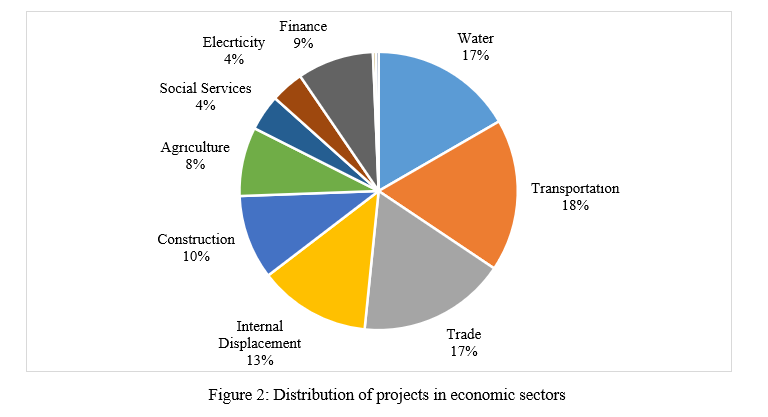

The highest percentage of projects were implemented in the transportation sector compared to the other sectors, as shown in Figure No. (2). These projects mainly contributed to the restoration of main and secondary roads destroyed by the war. These roads were vital to connecting villages and cities and facilitating civilian movement and trade. Water, sanitation, and trade projects came in second and third with 17% each, and the internal displacement sector ranked fourth at 13%.

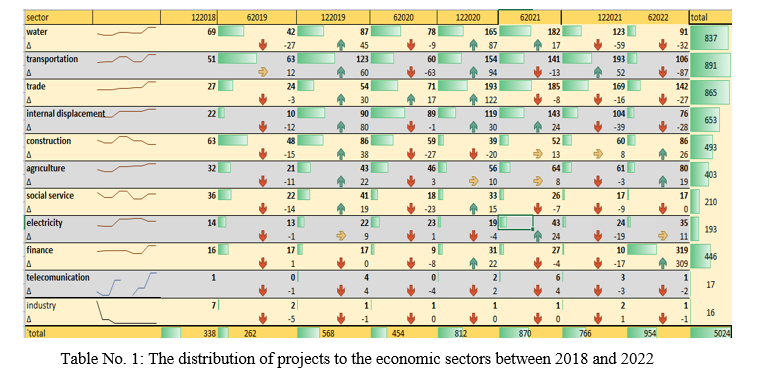

In more detail, Table No. (1) shows the sectoral survey on recovery projects during the observed period, where 891 projects were implemented in the transportation sector, 865 projects in the trade sector, followed by the water and sanitation sector with 837 projects. These projects were central to the recovery process in the region as they extended new water and sewage networks, repaired old networks, performed periodic maintenance, and repaired faults if they occur, such as paving roads, sidewalks, and commercial markets with asphalt and stone. Although these projects are still referred to as relief, they supported 1,293 camps, with a massive number of internally displaced persons, to access support and services. Projects related to construction were relatively low, around 487 projects were implemented, that included residential complexes for those displaced and the issuing of licenses for commercial and residential buildings. Agriculture projects were also lower, as farmers are reluctant to farm, there were only 403 projects during the observed period. The industrial, communications, and finance sectors are also suffering at the bottom of the index, due to the security situation and lack of investment in the region.

Distribution of Projects According to Regions

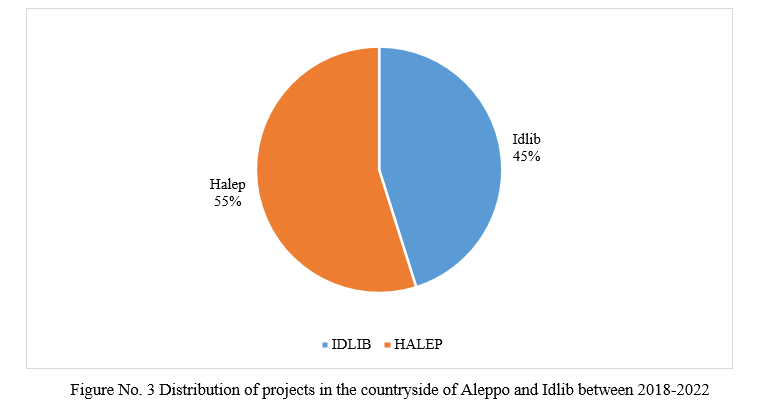

Figure No. 3 shows the distribution of projects between the countryside of Aleppo and Idlib between 2018 and 2022. The countryside of Aleppo had the largest percentage of projects with 55% about 2,757 projects were implemented in many towns and cities, most notably Azaz, Al-Bab, Afrin, Jarablus, Qabasin, Bza’a, Marea and others. The remaining 2,267 were executed in Idlib, Sarmada, Dana, Atma, Harem and others in Idlib governence.

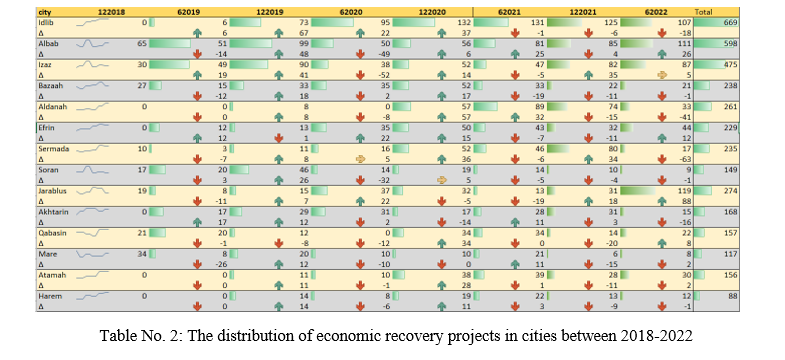

Table No. 2 shows the detailed distribution of projects at the level of towns and cities, where the city of Idlib appears at the top of the index with 669 projects, most of them in the sectors of internal displacement and trade. The city of Al-Bab, in the countryside of Aleppo ranked second with 598 projects in the sectors of housing, construction, trade, water and sanitation, and then Azaz with 475 projects in the sectors of water, transport, and electricity. A number of factors contributed to the discrepancy in the number of projects in cities and towns, including population density, displaced people and organizations, the centrality and importance of some cities before the revolution, the location of towns and cities on trade lines or near crossings, security situation, and lastly the concentration capital in some cities more than others.

Recommendations

Local councils and organizations have implemented important projects that pushed the early economic recovery process forward. Indicators of stability are also more apparent than before. With over four years of monitoring economic recovery activities, reports have highlighted the strengthened national negotiation papers while contracting investment companies to bring in investments. Furthermore, the industry, agriculture, communications, and finance sectors remain a significant challenge in the region’s recovery and attracting funds and investments. This is due to the lack of policies and laws necessary to enhance confidence in the local economy and products, the shortage of raw materials, high prices of raw materials, and the decline in purchasing power, in addition to the fact that the region remains trapped in relief projects.

Among the report's recommendations is to support local councils with good governance policies and implementation within each sector. This would ensure and support workflow, helping them be more attractive for investments. Support in the financial sector would revitalize the other sectors and create a comprehensive identity for the region within the agricultural and industrial sectors. As a result employment oppoturnities would increase, thus supporting residents with more jobs and a sustainabile livelihood.

Workshop | The Security structures in the liberated areas

On November 28, 2019, in Gaziantep, the Stabilization Committee in partnership with KALmec (Kalyoncu Middle East Research Center) has held a workshop entitled ‘’the Security structure in the liberated areas’’.

In the second section the Executive Director of Omran for Strategic Studies Dr. Ammar Kahf, talked about the security structure in the region. He asserted that the figures given in the presentation prepared by the Stabilization Committee are correct; he said we are sure because we have been working for two years now to collect information on bombings and terrorist attacks taking place in the region. He also said we should work to regulate relationship and strengthen coordination between the military, police and civilians through focused sessions on reference, governance, transparency, organization and administrative control.

The Workshop attended by the Syrian Interim Government’s Minister of Justice and the representative of Syrian Interim Government’s Interior Ministry, alongside Heads of Local Councils, representatives of civil & military police forces, representatives of Military factions, lawyers, Judges and CSO representatives in the northern countryside of Aleppo. As they are directly concerned with the security issues in the liberated areas in North of Syria.

Centralization and Decentralization in Syria: Concepts and Practices

Introduction

After seven years of conflict between the people and the Assad regime, Syria is now going through a difficult phase. The nature of the conflict has transformed whereby the role and effectiveness of local actors has been greatly maringalized compared to an increasing role for international state and non-state actors. The role of armed opposition factions has diminished as international military, administrative, and political influence has grown. These armed opposition actors are also in a phase of turmoil as they struggle to survive or integrate under direct international custodianship, after having previously received support from the Northern or Southern Operations Rooms. This process follows the series of meetings in Astana and Sochi, and after the political bodies were domesticated into official negotiating bodies that support the interests of countries with direct influence over them. At the same time, direct Russian influence came to dominate the political, military, economic, and administrative spheres. As a result, the concept of the unified framework of the "regime platform" versus the "opposition platform" in accordance with the Geneva II concept was discarded through the creation of several negotiating platforms on the sides of the opposition, the regime, and the Syria Democratic Forces (SDF).

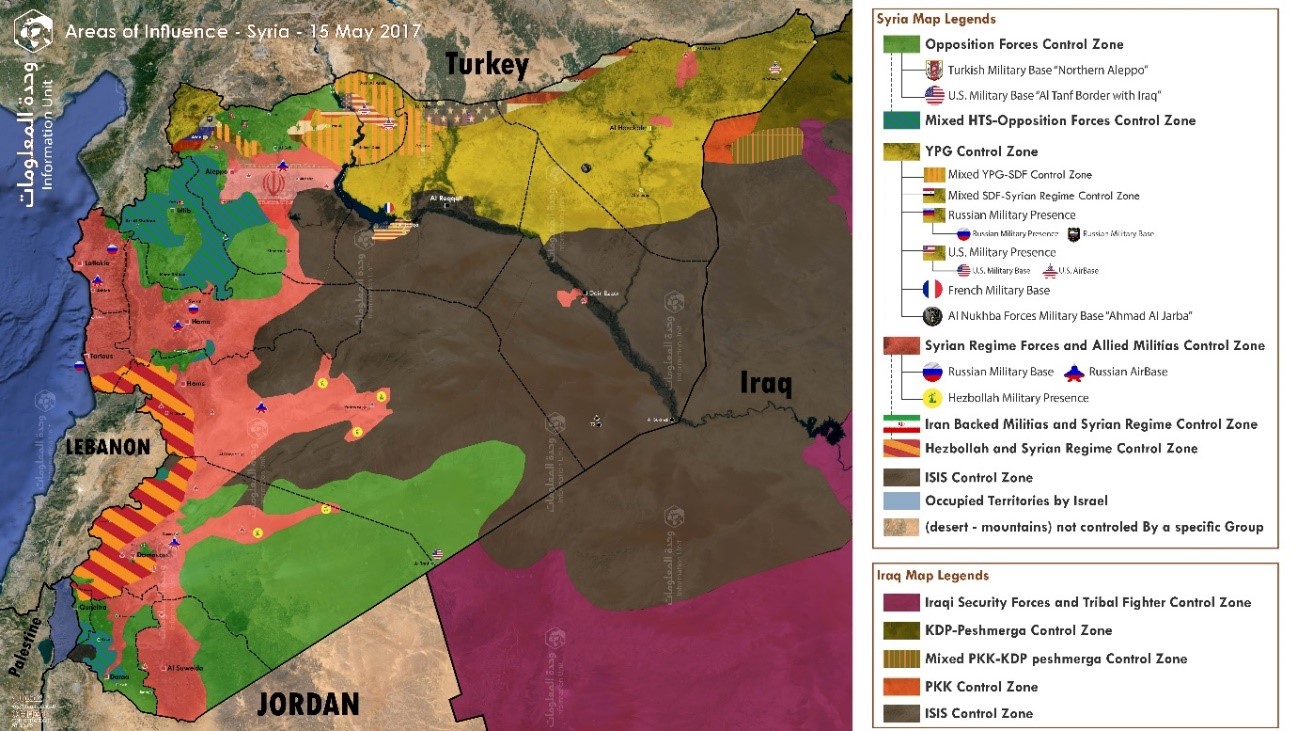

At the same time as these political changes were happening, the areas of influence and control on the ground were consolidated in 2018 into the north and northwestern portion under Turkish control, the northeast under the U.S. and SDF control, and southwestern Syria under the influence of the U.S. and Jordan, allowing Israel to strike any sites that it deems threatening. The areas of siege and opposition group control have been eliminated. International and regional influence has thus become more distinct, as efforts to control and integrate both armed opposition and pro-government groups continue.

This new phase is characterized by a complex series of partial deals that build on one another, and the arrangements among the state actors are developing in a "step by step" policy approach. The "counter-terrorism" framework that was used to justify the entry of these countries into Syria, is no longer a justification for their continued presence and influence: the U.S. is increasingly focused on the "Iranian threat;" Turkey is focused on "fighting the PKK" and security its borders; Israel justifies its interventions with the need to protect its borders against the "Iranian threat" and to prevent the transfer of weapons and fighters toward its borders; and Jordan is now also interested in protecting itself against the “Shi’ite crescent".

In light of this new landscape, contributing writers to this book discuss several aspects of Syria's current form of governance and how experiences on the ground in the different areas of influence converge or diverge from the concepts of centralization and decentralization, both vertically and horizontally. Towards this end, the chapters of this book first clarify the concepts and forms of decentralization and the way they are applied in post-conflict countries. They highlight the important role that agreeing on the form of governance and power sharing is an important factor in maintaining territorial unity and in shepherding negotiations to a more relevant stage of the new post-conflict reality. Next, the authors delineate decentralization in terms of its political, security, financial, and developmental functions, and review the constitutional and legal foundations of administrative and political decentralization in Syria. Finally, the authors present the experiences and applications of governance since 2011 in the regime-controlled areas and opposition-controlled areas, as well as in the SDF-controlled in northeast areas of the Democratic Autonomous Administration. Woven throughout the book are comparative descriptions of the experiences from Iraq, Lebanon, and other countries emerging from conflict, to see what lessons can be learned from the ways that these countries have negotiated the distribution of powers between central and local administrative units.

This book aims to help lay out a path towards the restoration of the legitimacy lost by all parties in Syria through the organization of local governance tools based on the experience of local councils. Local councils have tended neither towards excessive forms of decentralization nor to authoritarian centralization, but have instead followed a path that strengthens local structures and sets limits to central state authorities by granting powers rather than delegating them. At this stage, it is essential to work in parallel on strengthening the central government while also safeguarding and reinforcing the gains of the local councils through constitutional guarantees and a new local governance law. This book also stems from recognition of the need to shift away from limited centralized negotiations among the two “sides of the conflict” through a constitutional process followed by general elections, towards a negotiation based on power-sharing arrangements. Local governing bodies and other local actors should be engaged in the process of deciding which functions and authorities are mandated to the central institution versus the local governing units.

The chapters of this book were contributed by several researchers who differ in their approaches, but they all agree on the need to develop a decentralized Syrian model that avoids the reductive binary approach of political decentralization / administrative decentralization or federalism, and one that is based on the sharing of powers and functions, thus transitioning Syria’s system of governance from local administration to local governance. There is no doubt that further development and discussion of these ideas is required, but we present this effort as a starting place for a dialogue in the Syrian community on the most authentic or locally developed form of governance for Syria, which after years of adhoc decentralization, has become more localized than ever before.

Finally, it is important to note that most chapters were written in late 2017 and early 2018, which was before the change of control of Damascus suburb, northern Homs and the southern front. The arguments for a tailored and customized Syria-centric decentralization model put forth are still valid regardless of the controlling armed party.

Executive Summary

Chapter one of the book focuses on the concept of decentralization and illustrates the differences among countries when it comes to choosing how they exercise administrative authority. Every country’s approach to governance is influenced by its political and social conditions, as well as the maturity and depth of its democratic practices. The need to shift towards a decentralized system becomes apparent after examining factors related to a state’s nature, size, and degree of political stability. Decentralization becomes a necessity for stability in some countries because of its core idea: the distribution of power and functions of state institutions between the central governments and local administrative units. This conceptualization reaffirms the fact that the transformation to fully decentralized system may be risky for many governments, despite the promise that decentralization holds as the solution for most conflicts in developing countries such as those in the Arab world. Chief among these problems is the need to expand the political and economic participation of citizens. Still, given the ethnic and sectarian diversity and complex nature of countries, decentralization can be a threat to state unity.

Chapter two describes political functions of the state in a decentralized system and how it is practiced in different versions of decentralization. Political functions of the state take many forms depending on the degree of decentralization and mode of local governance. The far end of a decentralized governance system continuum appears in the practice of full political decentralization (full federalism), where provinces and regions have their individual constitutions and laws, exercise special legislative, executive, and judicial powers, and influence federal government policy through a political oversight authority and through their representatives in the legislative branch councils. Local governments, meanwhile, exercise specific roles in these functions under the partial political decentralization within their constitutionally-vested authority. These roles are primarily related to domestic policy-making and the development of local rules and regulations that do not contradict federal legislations. In administrative decentralization modes of governance, the practice of political functions and duties is reduced to a great extent as it focusses exclusively on administrative and executive functions of local governing institutions. Local administrative units would then be fully subordinated and controlled by the central administration in the capital. In partial administrative decentralization modes of local governance, political functions completely disappear from local units.

According to chapter three of this book, the exercise of legislative and judicial functions within a decentralized system will require reforms in the Syrian judicial branch, such as: the restructuring of the Supreme Judicial Council to ban the executive branch from holding membership in it and stop its interference, and the repeal of laws that encroach on public rights and freedoms with judicial not executive branch oversight. Assessing the current form and content of the Syrian Constitution in terms of centralized or decentralized approaches highlights centralism as highly visible and grants authority to the presidency (which has broad constitutional powers) to override all other authorities and functions of the state. Instead, the principles of separation and distribution of powers should be applied to three independent bodies in order to create balance and cooperation between them. With regard to legislative duties in Syria, this paper shows that the Constitution has broadly granted legislative duties to the People's Council of Syria (Parliament) and the President of the Republic, transforming the mandate of the Parliament from drafting laws to ratification of presidential laws. Reforming this imbalanced structure requires redefining the scope and mandate of the Parliament, abolishing the broad powers granted to the President, and reducing the centrality of legislation process and parliament. There needs to be a shift toward some kind of decentralization that divides future legislative functions in a balanced approach between the exclusive jurisdiction of the legislative branch, and the jurisdiction of the executive branch for all that is not stated in text of the constitution.

The fourth chapter focuses on security functions in decentralized systems. In the context of conflict-ridden or post-conflict countries, it is critical and necessary to re-assess national security functions: their applications, mechanisms for implementation and governance, and how security roles are distributed at different levels of government. This paper emphasizes that the redistribution of security duties and authorities in decentralized countries (in accordance with the lessons from stable and unstable countries) may result in a more efficient and coherent security architecture depending on who and how such a process is executed and whether by means of national actors, cross boarder actors, or international actors. In the search for a governing framework of the Syrian security sector within a decentralized system, independent intelligence agencies should have a clear mandate of intelligence gathering only (except for police forces and anti terrorism units that can arrest citizens) and an identified geographical jurisdiction. Local governing bodies should be constitutionally mandated to provide local security services and conduct police functions and duties locally. The assessment and identification of security threats and risks and the counter strategy to such risks should be developed locally and shared with central agencies for coordination.

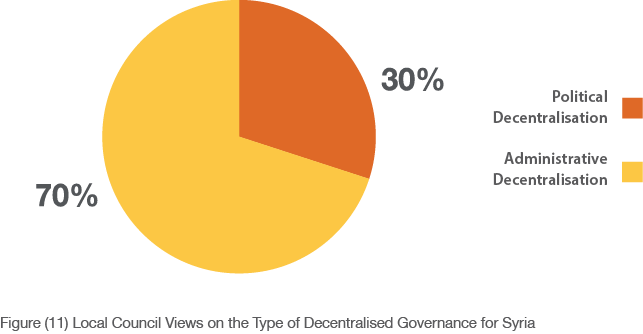

The fifth chapter highlights the dialectical relationship between decentralization and its role in local development in countries emerging from conflict. Local development is one of the most important determining factors in whether or not decentralization is adopted in these cases. While some of post-conflict countries have reached acceptable rates of economic and social development after moving to a decentralized system, others have not. This disparity may be due to factors linked to each country’s particular local development process and adopted form of decentralization. This paper emphasizes that in the context of the Syrian situation, the country has suffered from the absence of a clear developmental model for decades. This has led to major developmental imbalances at the central state level, which are most evident in the developmental disparities between Syrian governorates. The adoption of a model of administrative decentralization in Syria will help to mitigate this disparity by empower local communities to participate in the local development process.

The sixth chapter, which deals with financial decentralization, emphasizes the fact that the successful implementation of decentralized systems of government in post-conflict countries depends largely on their ability to establish regulatory frameworks for financial decentralization and mechanisms for the collection, distribution, and disbursement of financial resources at various levels of government and administration. Successful implementation also requires substantial reforms in fiscal policy in general and in spending policies in particular. This paper finds that that the model for allocating financial resources to the local administrative units out of the state budget in Syria has many flaws. It is necessary to grant administrative units greater financial independence and to define metrics for successful financial decentralization to measure whether these units are meeting developmental requirements and making effective contributions to economic and social stability in their regions.

The seventh chapter examines the reality of local administration in regime-controlled areas. It illustrates the dominance of the central government in the local administration systems in regime-controlled areas, the growing influence of the Baath party, and the increasing influence of local Iran-backed forces in the operations of some local administrative units. This paper finds that the service sector crises in the areas of local administration units are indicative of their lack of funding, dysfunctional mechanisms, and insufficient personnel, forcing them to rely on the central government to conduct their affairs. It also argues that the regime is not interested in decentralization – which runs counter to its desire to retain centralized control – but it does use decentralization politically as a bargaining chip for negotiations with the international community, particularly the Europeans. The regime also attempted to manipulate the boundaries of the electoral constituency of administrative units to change administrative districts and weaken opposition areas by preventing them from winning elections in their areas while rewarding loyalists.

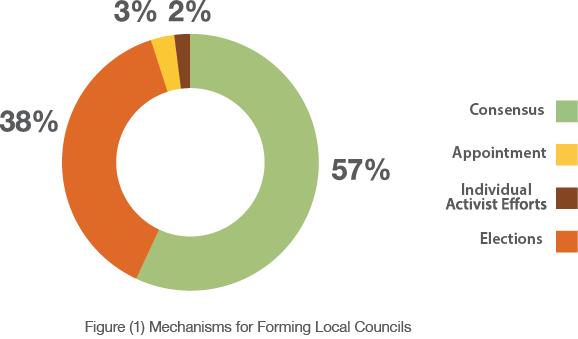

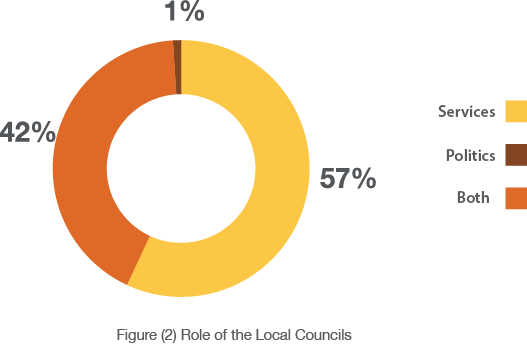

The eighth chapter focuses on the reality of governance in Syrian opposition-controlled areas. It reaches several conclusions, the most important of which is that local councils have undergone changes in terms of structure, mechanisms of formation, and function, as their organizational structures have stabilized and they rely increasingly on the elections for their membership. They have also been able to consolidate their service roles, compared to their role in local security and politics. The financial file is one of the primary challenges facing local councils as they cope with growing financial deficits, due both to the nature of revenues and expenditures, and also their lack of financial systems or laws regulating their budgets. This chapter explains how the long duration of the conflict, the transformations in its nature, the push towards coexistence, and the survival of the regime have all stimulated competition between local actors, of which the local councils were one of the most prominent players due to their political value and local legitimacy. As a result of the way the local councils have dealt with these challenges and threats, they face one of three scenarios in the foreseeable future: vanishing entirely, forming regional or cross-regional self-administrations, or continuing the current independent local units structures.

The ninth chapter analyzes the reality of governance in the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. It shows that lack of transparency is a key feature of service delivery, financial administration, and the management of strategic resources within the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. The process of forming legislative councils (mandated to pass laws) in these areas was based on partisan consensus that relied primarily on the literature and system of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM). Laws passed by these legislative councils, such as laws related to self-defense, changes to school curricula, and civil status laws, are problematic. A review of the structure of the DAA and its legislative and executive bodies, shows the presence of a partisan political project that is being forced on the local population through its security and military apparatuses. This paper concludes that the DAA, though able to impose a unique governance model, still suffers from problems of representation, legitimacy within its population, and a lack of competent personnel, and it has failed to eliminate the local and regional concerns arising from this project.

The tenth and final chapter of this book proposes a unique Syria-customized decentralized framework, one that takes into account the importance of achieving stability. It highlights the importance of refocusing international negotiations on two parallel tracks: negotiations policies to strengthen central state institutions in order to create conditions for peace and stability, and empowering local governance models through local negotiations on power sharing of authorities and functions of the central state with local administrative units. They must also revisit the basic Geneva Communiqué according to the principle of power sharing agreements between the center and periphery and not only a central agreement where the opposition and regime share authority. This means prioritizing internationally-monitored elections over any other track, beginning with local administration elections.

In order to ensure the success of the elections, essential actions are required from the different parties with regards to the restoration of the functionality of police and local courts. It is therefore necessary to begin drafting a new law for local administration (decentralization) to allow locally-elected authorities to have full control over the work of the police and administration of local courts.

The opportunity exists for local councils to legitimize their structures and negotiate new authorities, guaranteeing a decentralized model that provides expanded authorities to the councils and governorates, based on the strength of their electoral legitimacy. This chapter emphasizes the need to empower the tools and foundations of local governance both constitutionally and legally, and to ensure that the countries with a presence on Syrian soil help push the negotiations to a peace-building stage and guarantee relative stability on the ground until an agreement on the various security arrangements is concluded.

for More Click Here: http://bit.ly/2B2Vxqd

Meeting entitled “Local Councils and Security Sector Reform in Syria”

The representatives of various public institutions and diplomats serving in the Embassies in Ankara attended the meeting as well as OMRAN and ORSAM representatives. Two reports prepared by OMRAN Center experts with respect to the local councils and security sector in Syria were presented at the meeting.

The Role of Jihadi Movements in Syrian Local Governance

Executive Summary

-

Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), exemplifies how international extremist jihadi organizations, such as Al Qaeda, have evolved in Syria. Informed by the experiences of Al Qaeda and other jihadi groups in Iraq, HTS has developed a governance strategy that depends on building support from the local Syrian population.

-

In Idlib province (Syria), a few local administrative bodies that provide critical social services are affiliated with HTS. Others are affiliated with Ahrar al Sham and Jaysh al Fateh. Some, however, are affiliated with opposition Local Councils and civil society organizations.

-

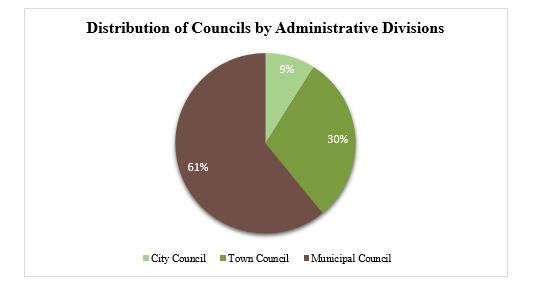

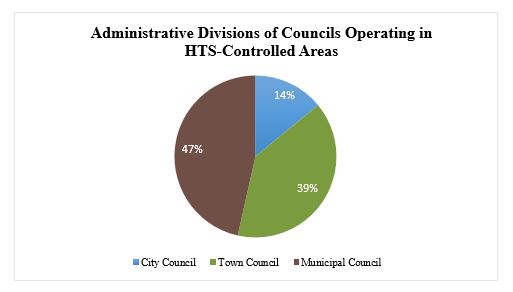

Local Councils are responsible for local administration of services in coordination with the Syrian Interim Government. Currently, there are 156 Local Councils operating in Idlib province with the following administrative divisions: 9% City Councils, 30% Town Councils, and 61% Municipal Councils. Of these Local Councils, 86 operate in HTS-controlled areas—14% City Councils, 39% Town Councils, and 47% Municipal Councils.

-

Equipped with the combined experiences of its affiliated jihadi groups, HTS aims to gradually establish a permanent presence in Syria and create a state under “Islamic law” in one of three forms, an emirate, Islamic state, or caliphate.

-

HTS’ local governance strategy depends on three elements, 1) providing social services, 2) enacting coercive policies of public order, and 3) propagating its religious and political ideology. To support this strategy, HTS operates through four main bureaus, 1) General Administration for Services, 2) Military and security operations wing, 3) Dawah and Guidance Office, and 4) Sharia courts.

-

HTS establishes a relationship with the local population through cooperation (mutual interests), containment and infiltration policies, or exclusionary measures. The type of relationship is determined by HTS’ strength and control in a respective community, available resources, local support network, the strength of Local Councils, and the presence of other armed groups that support and protect Local Councils.

Introduction

Extremist Jihadi movements aim to seize territory in order to govern it; however, each movement has a different perspective on the type of governance, level of institutionalization, and mechanisms necessary to fulfill its vision for governing the territory. Some jihadi movements, such as the Islamic State, are aggressive and force a specific ideology on local communities. They spend less time providing basic goods and services, attending to the needs of the community, or managing their views on life or Islam. Other groups, such as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)([1]), pursue a relationship with the local communities based on mutual interests, managed by a combination of positive and negative incentives.

HTS, which formed from multiple jihadi groups including Al Qaeda, developed with essential insight and experience from various fronts of the “Global Jihad.” HTS used a combination of the following strategies to establish an effective local governance structure: providing social services, executing policies of coercion, and spreading its ideology—all through a specifically crafted structure cementing its presence in Syrian society for the long term.

No group understands the dangers of HTS efforts to establish local governance better than the Local Councils([2]), which in this case are faced with an extraordinary challenge. This study analyzes the possible impact of the HTS’s local governance on the Local Councils in Idlib province. This province was chosen for the case study for the following reasons: 1) it is the only province that is nearly completely outside of the control of Assad central state; 2) its geographic location, connecting coastal Syria with central and northern regions and Turkish border, is significant; 3) it has the most Local Councils of any other province controlled by opposition forces; and 4) it is the main stronghold for the HTS.

First, this study compares the governance methods of the HTS and Local Councils in the areas under HTS control. Second, this study explains how the HTS became involved in local governance and how it interacts with the Local Councils.

This study is part of a larger effort to understand the state of governance in all Syrian territories in order to reach a consensus on how to deal with these new circumstances during and after the political transition. This study compares local governance policies of HTS and the opposition Local Councils beginning with a description of how the HTS was formed and its involvement in local governance bodies. Next, this study offers a description of Local Councils that operate in HTS-controlled territories and examines the relationships between the Local Councils and the HTS. This study concludes with a number of recommendations on how to empower Local Councils in areas under HTS control to avoid their cooptation. This study was conducted based on interviews with Local Council members and analysis of open source information such as news articles, reports, and social media postings.

Formation of HTS: Specifically Crafted Structure

Some argue that HTS is merely a façade for Jabhat al Nusra (see section one below on the formation of Jabhat al Nusra), which attempts to curtail local and international pressure after the fall of Aleppo and the start of the Astana talks. Others claim that HTS is loyal to its core Al Qaeda leadership, and the reason for adopting the name HTS reflects recommendations from its central leadership to integrate into the local communities. Finally, some attribute the formation of HTS to a culmination of various groups competing to represent the “Syrian Jihad.” Because these perspectives offer only a partial understanding, our study provides a comprehensive analysis of HTS structure and governance as a major byproduct of Al Qaeda, a constantly changing cross-border Salafi Jihadi movement.

HTS has focused on the following major themes in order to establish itself in local communities: its relationship with the international community, jihadi experiences in Iraq, its relationship with Al Qaeda, competition with other rebel groups, and local support.

HTS developed its current structure as a result of three phases:

1.Jabhat Al Nusra – January 2012-July 2016

Jabhat al Nusra was formed in January 2012 with help by Al Qaeda’s branch in Iraq. The group adopted a patchwork of religious ideologies reviewed by Al Qaeda’s central branch. The leader of Jabhat al Nusra, Abu Muhammad Al Jolani, made it clear that he wanted to avoid mistakes made during the Iraqi Jihad, and declared his commitment to Al Qaeda’s newfound ideology. In the beginning, Jabhat al Nusra refrained from publicly affiliating itself with Al Qaeda despite its public praise for the group. It also avoided international attention by presenting itself as a native Syrian organization. Jabhat al Nusra immersed itself in the local communities and concerned itself with society’s general demands, such as standing up to the Assad regime. The group also took advantage of the revolution to expand its presence in Syria, exercise its military strength, and create mutual alliances with the locals. The group also benefited from a significant boost in membership after the Assad regime released prisoners affiliated with jihadi movements.([3])

However, Jabhat al Nusra also has faced a number of challenges:

- Jabhat al Nusra’s designation as a terror group by the United States in January 2012 and by the United Nations in 2013

- Conflict with Al Qaeda in Iraq in April 2013 following the establishment of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levent (ISIL) and its subsequent caliphate in March 2014

- Jabhat al Nusra’s public acknowledgement of its loyalty to Al Qaeda, and the negative reaction from Syrian revolutionaries as a result

- Russian intervention in Syria in September 2015

Jabhat al Nusra dealt with all of these challenges and eventually adapted into a new organization in July 2016 under the name Jabhat Fateh al Sham (JFS)([4]).

2.Jabhat Fateh al Sham (JFS) – July 2016-January 2017

Al Jolani personally announced the termination of Jabhat al Nusra and the formation of Jabhat Fateh al Sham (JFS), emphasizing that the new entity would have no ties to Al Qaeda. He explained that the organization made this decision to meet the demands of the Syrian people, who wanted to protect and strengthen the “Syrian jihad” and avoid claims from the international community that Al Qaeda elements exist in the Syrian opposition([5]) . It seems Al Jolani intended to improve the group’s relationship with the international community by announcing its independence from Al Qaeda and insisting upon its closeness to local communities. This new group presented an opportunity to regain local support for the jihadi project, for which support had dwindled following a series of Russian, regime and US led international coalition military strikes on opposition-controlled areas under the pretense that Al Qaeda-linked Jabhat al Nusra forces were present in the area. This new group also sought to appease some locals who were displeased with Jabhat al Nusra’s interference in local affairs, which had created popular unrest.

JFS also emerged as a result of competition between Jabhat al Nusra and Ahrar al Sham ([6]), to dominate the “Syrian jihad.” Al Jolani wanted to put pressure on Ahrar al Sham by draining its resources through a new jihadi coalition and bringing into question its jihadi qualifications.

But the presence of Abu Abdullah al Shami and Abu al Faraj al Masri, who are Al Qaeda linked Jihadi leaders inside Syria that were also affiliated with Jabhat Al Nusra, during Al Jolani’s announcement confirmed Al Qaeda’s implicit influence on JFS and provided the new group with credibility among jihadist organizations.

JFS endured repeated attempts to isolate and eliminate the group, especially following the eastern Aleppo deal (12/13/2016), Ankara’s cease fire deal (12/30/2016) and the Astana meetings (01/23/2017). The international community ultimately designated JFS as a terror group, even though it included non-terrorist factions close to the West, such as Nur al Din al Zinki. To prevent being targeted by the international community, JFS had no choice but to announce the formation of HTS at the start of 2017.

3.HTS – January 2017

HTS formed from a combination of opposition groups in northern Syria at the end of January 2017. These groups included JFS, Nur al Din al Zinki, Jabhat Ansar al Din, Jaysh al Muhajireen wal Ansar, and Liwa al Haq. A number of jihadi and Salafi leaders joined HTS, as well, including Abdul Razaq al Mahdi, Abu al Harith al Masri, Abu Yusuf al Hamwi, Abdullah al Muhaisni, Abu al Tahir al Hamwi, and Musleh al Iyani.

Furthermore, HTS emerged due to the continued competition between Jabhat al Nusra and Ahrar al Sham. HTS attracted more than 25 opposition fighting groups from its competitors, 16 of which came from Ahrar al Sham([7]). Ahrar also lost a number of its prominent leaders to HTS including Abu Saleh Al Taha and Abu Yusuf al Muhajir.

The new group confirmed Al Jolani’s intentions to firmly establish the jihadi project in Syria and salvage its legitimacy. HTS adopted many of the revolutionary slogans used in local revolutionary circles([8]). Through its media campaign, HTS expressed approval for a conditional political negotiation and demonstrated a willingness to fight the “Khawarij,” who are a historically marginal yet significant group of Muslims that are considered more extreme and radical.

HTS comprises approximately 19,000 to 20,000 members, including administrators, fighters, and religious figures. HTS has a significant presence in some Syrian territories with well-known bases and checkpoints. In other areas, HTS has a limited presence where it merely patrols the area. HTS forces operate in Idlib province, southern and western Aleppo, Jarood al Qalamoon, eastern Ghouta, and Daraa province, minimally. (See map below for reference.)

Figure 1: Map of Territories in Syria as of May 15, 2017

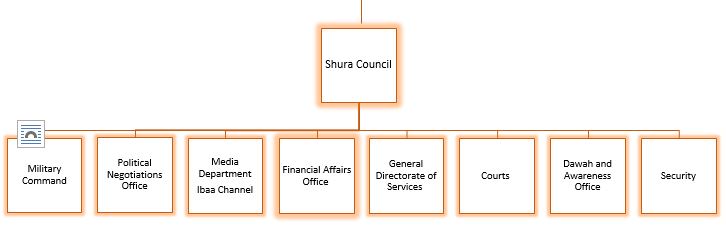

Based on information surveyed and interviews, HTS operates through eight divisions, namely military, security, services, religious law, courts, media, finances, and politics. For each of these divisions, there is an office organized under the leadership of the “Shura Council.”

General Commander of HTS

Figure 2: HTS Command Structure

The HTS administrative structure suggests that the group is organized and tied directly to a central leadership body, which implies that HTS aims to establish a permanent Islamic governing structure. This structure is a direct threat to the Local Councils, the primary entities leading efforts to rebuild the nation.

HTS Management of Territory and its Relationship with the Local Councils: Road to Permanence

Jihadi movements with military wings seek to administer the territories they control in order to achieve their goals, but each movement differs in its approach to governance. In an attempt to avoid conflict, some jihadi movements focus on providing social services rather than forcing a particular ideology on local communities. Other groups take the opposite approach, regularly forcing locals to accept a specific ideology in order to secure a permanent presence. Here, it is important to shed some light on HTS’s experience with local governance, the methods and resources it requires to effectively govern, and its relationship with Local Councils in HTS-controlled territories.

HTS Perspective on Local Governance: Picking from the Most Successful Jihadi Practices and a Pragmatic Approach

HTS aims to establish a permanent presence gradually and to create an Islamic governing structure, such as an emirate, an Islamic State, or a caliphate. HTS’s governing structure is a collection of best practices gathered from its affiliate groups and other jihadi groups around the world ([9]).

In its attempts to establish a permanent presence through an Islamic governance structure, HTS affords the local community a status of great importance. HTS considers the local community a key actor, which has the capacity to carry forward the HTS project or bring it to an end. For this reason, HTS employs a number of strategies to gain support from the local community, such as 1) providing social services, 2) enacting policies of coercion, and 3) spreading a radical s ideology. Several factors that distinguish HTS from other groups include its level of presence and control in the areas it governs, the amount of resources invested in its governing structure, the results achieved, and the people responsible for making decisions and carrying out the project.

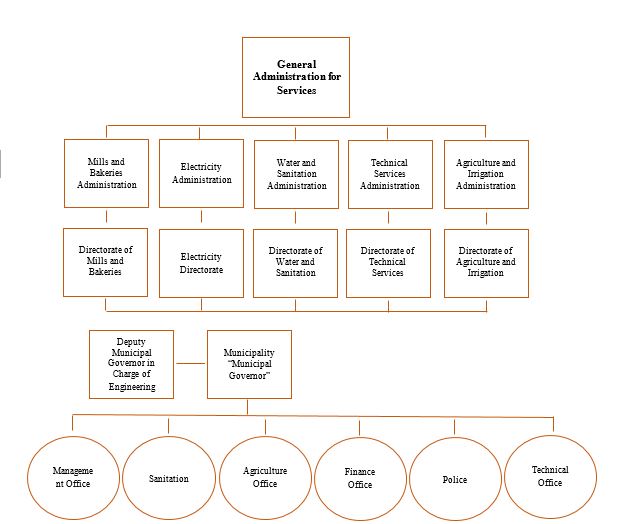

1.Providing social services: General Administration for Services

The General Administration for Services is responsible for providing social services in HTS territories. The administration was formed under Jabhat al Nusra in 2013, when the organization decided to separate from the Islamic Administration for Services ([10]). The General Administration for Services is made up of several divisions established based on general geographical distribution (Idlib, Aleppo, Hama, etc). These divisions, similar to ministries, are connected to specific service offices, such as the Border Services Office, Desert Services Office, and Aleppo City Services Office. All of the offices are managed by a municipal administration, under the authority of the General Administration for Services. These local offices carry out the policies of the General Administration for Services ([11]). Through these offices, HTS interacts with the local community by providing important services. Some of these communities include Harem, Salqeen, Darkoush, and Talmins. In areas where HTS does not control the municipal offices, the General Administration for Services either directly coordinates with established service structures (via Local Councils) or independently provides the necessary services)[12]). If HTS is unable to provide services then Local Councils provide them, but HTS still maintains a significant influence over them ([13]).

Figure 3: Structure of the General Administration for Services ([14])

HTS knows well the importance of providing services to the local community in order to garner support and recruit new volunteers. HTS also knows that if it can provide basic services, it may weaken its competitors. Furthermore, if community members receive services from HTS, they may be more willing to accept the organization’s coercive methods of spreading its ideology. HTS cannot afford the high costs of providing all necessary services, so the group focuses on providing only the most important ones, such as electricity and water, through which it can significantly influence the Local Councils ([15]). In the meantime, HTS can diversify the kinds of services it offers as more resources become available, if such provisions will help the organization establish a permanent presence in the territories it controls.

HTS employs local civilians in social services jobs in order to maintain positive relations with the community ([16]). As for funding the services, HTS depends on its external support networks, both from the central leadership and from its supporters. HTS also levies taxes on the local community. Additionally, people passing through HTS-controlled territories must pay a road tax, which is especially lucrative in the crowded areas of northern Syria and along important supply lines( [17]) . Furthermore, organizations that want to operate in HTS territories must also pay for protection and permission to operate there ([18]). HTS also collects fines from those who violate its rules. In addition, HTS also buys and sells properties.

2.Policies of coercion: Violent and non-violent tactics

HTS also resorts to coercive measures against its adversaries. The organization justifies its coercive policies against those engaged in immoral acts, cooperating with the West or the Assad regime, and when applying Sharia law. HTS uses military force to execute its coercive policies, evidenced by its operations against opposition groups in northern Syria, including the Jabha Shamiya, Fastaqim, Suqoor al Sham, Jaish al Islam, and Jaish al Mujahideen ([19]). HTS security branches ([20]) also force locals to adopt the group’s worldview, and they punish those who do not comply.

HTS uses indirect coercion and non-violent means to force its worldview on the locals and create a shared ideology. This strategy is managed by HTS’s Dawah and Guidance Office, which is responsible for spreading the group’s ideology, and the media office, which is responsible for generating propaganda. The two offices organize and offer religious courses and programs in mosques and public places, where they can spread HTS ideology and organize protests against their competitors ([21]).

3.Ideology: The duality of courts and advocacy

Informed by the experiences of Al Qaeda, HTS gradually implements Islamic law, or Sharia, to avoid clashing with local populations ([22]). HTS depends on a two-pronged approach, comprising the courts and Dawah, to gain support from the locals. On one hand, HTS has inherited a court system established by Jabhat al Nusra in Salqeen, Sarmada, and Darkoush. By controlling the courts, HTS gains the locals’ trust by implementing policies according to its interpretation of Islamic law ([23]). This position of power also allows the group to act with impunity by exploiting religious ideology to justify unpopular actions, such as commandeering public goods or property, or those of its competitors ([24]). On the other hand, HTS depends on its Dawah and Guidance Office ([25]) to conduct ideological campaigns to convince local communities to support its project and adopt its vision. HTS has demonstrated greater success in spreading its ideology in rural areas compared to more populated areas in Idleb province, such as Muarat al Noman, Saraqeb, and Kafranbal. These areas have well-developed civil societies making it much more difficult for HTS to infiltrate them.

HTS’s Relationship with Local Councils: An Approach Based on Mutual Interest

Amid the ongoing conflict in Syria, Idlib province is significant for several reasons. First, it is the only province that is nearly completely liberated. Second, it is positioned in a strategic geographic location, connecting coastal Syria with central and northern regions. Third, it has the most Local Councils of any other opposition-controlled area. Fourth, and finally, it is the main stronghold of the HTS. Our description of the services provided in Idlib province includes the Civilian Services Administration of Jaysh al Fateh, the Committee for Services Management of Ahrar al Sham, the General Administration for Services of HTS, the Interim Government’s service offices, and the Local Councils, as well as other civil society organizations. There are currently 156 local sub-councils operating in Idlib province ([26]).

Figure 4: Distribution of councils by administrative divisions

There are also a number of councils in the villages and rural areas of Idlib province that are not recognized as full-fledged councils by the Interim Government’s Ministry of Local Administration or the Idlib Provincial Council. These councils were formed by either the leaders of these localities seeking support from aid organizations or military groups attempting to increase their legitimacy among the locals ([27]).

There are 81 Local Councils operating in territories heavily controlled by HTS in Idlib province. They are categorized by following administrative divisions. (Please see the figure below.)

Figure 5: Administrative Divisions of Councils Operating in HTS Controlled Areas

A large number of these councils are affiliated with the Provincial Council of Free Idleb, which is a part of the Syrian Interim Government ([28]). Some of these councils have no affiliation with the Interim Government. The remaining 450 the councils, including those in Harem and Salqeen, are affiliated with the HTS-controlled General Administration for Services.

All of the councils differ in their effectiveness and their roles within the community according to the following factors: capacity, legitimacy, size of the administrative unit, military operations, and its relationship with HTS. Each council aims to provide basic services to its communities including humanitarian aid, infrastructure renovation, health care, sanitation, education, civil defense, local security, and civil society organizations.

The local councils finance their endeavors through a number of sources, the most important of which are cash donations, work project grants, or in-kind donations. The support they receive from the Provincial Council—and the Interim Government overall—is limited and inconsistent. Therefore, Local Councils must generate funds through local taxes, investments in public property, and income from development projects. In addition, the Local Councils, especially those directly affiliated with HTS, receive both financial and logistical support from the HTS General Administration for Services ([29]) .

It seems that HTS acknowledges the significance of the Local Councils, and for this reason, it provides services and develops close relationships with the local community, international community, and parties providing financial support to humanitarian aid and development projects in Syria. Each of these entities are essential players in implementing a future political solution.

HTS’s goal to establish a state under Islamic law conflicts with the political goals of the Local Councils, which form the essential basis for a state. For this reason, HTS pursues a relationship of mutual interest with the Local Councils governed by the following principles: 1) the level of permanence and dispersion, 2) availability of resources, 3) amount of local support, 4) central role of Local Councils and their legitimacy, and 5) Local Council partners.

Based on these principles, the HTS adopted the following approach:

- Cooperation “mutual interests”: HTS develops relationships with the Local Councils based on areas of mutual interest, such as electricity and water—both of which the General Administration for Services controls ([30]). HTS and the Local Councils negotiate the terms of their agreements ([31]), and in some cases HTS may request money, services or logistical services from the Local Councils in exchange for electricity or water ([32]). In other cases, the General Administration for Services may provide Local Councils with logistical or financial support for certain projects ([33]). In territories where HTS does not exercise full control, such as Saraqeb, the organization must build a relationship with the Local Council in order to become a part of the armed coalition responsible for controlling the territory ([34]). HTS also prefers cooperative mutual interest-based measures in places such as Muarat Al Noman, where it does not have a majority of the local support ([35]). Because Local Councils are able to choose whether to align with HTS or its competitors in providing services to the community ([36]), HTS must cooperate with the Local Councils and avoid unwanted interference in local affairs ([37]).

- Containment and infiltration: HTS aims to contain and infiltrate Local Councils to use as a tool[38] in its efforts to forge a permanent presence in the region. HTS uses this strategy in territories where it exercises full control and has a military advantage. HTS also employs this tactic in regions where it does not have the resources to control administrative bodies that provide local services. In areas where HTS has strong local support, such as the rural areas of Idlib, the organization increases pressure on the Local Councils, especially when the councils are ineffective. HTS contains and infiltrates Local Councils by planting HTS-affiliated individuals on the council ([39]) or demanding that an HTS-appointed representative attain a seat on the council ([40]). HTS also employs subtler tactics by influencing the process ([41]) of making a decision within any given council or carrying it out ([42]). (Refer to endnotes for elaboration from Local Council members).

- Exclusion: In places where there is no resistance, where HTS exercises complete control of a territory, the organization terminates all Local Council operations and replaces them with its own structures ([43]). This strategy is especially true in high-value territory, near main supply lines and areas near the border, such as Harem and Darkoush. HTS also adopts this strategy in 1) areas where local support is contested, 2) areas with poor local services, and 3) areas in which Local Councils refuse to allow HTS to play any role, such as in Sanjar ([44]) and Salqeen([45]).

Strengthening the Local Council System: Civil Society, Effective Management, and Resources

Idlib is critical as a case study to measure the performance of Local Councils and the potential for development in the future. In general, Local Councils in Idlib face a number of challenges due to a lack of resources, fierce local competition, and conflicting policies of various parties involved in the Syrian conflict. Local Councils operating in areas under HTS control face the possibility of termination due to HTS’s policies of coercion and infiltration.

The following are general recommendations on how to strengthen Local Councils, especially those operating in areas dominated by HTS and those that are losing credibility among the local population. In order to prevent the Local Councils from falling prey to HTS’s strategy (mutual interest-based cooperation, containment and infiltration, and exclusion), Omran for Strategic Studies offers these recommendations:

- Productive Civil Society: Establish a strong civil society to support and collaborate with the council to prevent HTS from taking control of local administrative bodies. To build a productive civil society in Syrian communities, consider the following steps:

- Teach the local population civil society empowerment skills through trainings and workshops on civil society activism and work.

- Create opportunities for open dialogue, such as town hall meetings, in order to increase communication between civil society organizations and the Local Councils operating in areas controlled by HTS militarily.

- Build public interest on issues of mutual concern, such as resisting efforts by armed groups, including HTS, to get involved in civil society activities. Local radio shows or newspapers can help achieve this step.

2.Effective Local Administration: Councils should have a clear structure and effective governance system that is protected from infiltration and capable of maintaining its operations in HTS-controlled areas. Consider the following steps:

- Assist the Provincial Council of Idlib in streamlining all of its projects, solely through the offices of the Interim Government.

- Provide training and financial/logistical support to the councils operating in HTS-controlled areas.

- Protect areas that the Assad regime, its allied militias, and Russian forces attack—which they justify by claiming that the areas are under HTS control.

3.Improved Local Resources: It is important to develop the financial and human resources available to Local Councils to prevent them from having to negotiate with HTS for shared control. In order to improve and increase the councils’ available resources, consider the following steps:

- Offer technical and theoretical training to qualified candidates to provide the council with necessary expertise. This includes for example trainings on good governance and public sector management.

- Provide council members with consistent salaries.

- Create new markets by developing alternative sources of electricity outside of HTS control.

- Create a fund to invest in for-profit endeavors that would help generate funds for the council.

- Train council members on how to manage public property and property taxes.

Conclusion

HTS is taking advantage of local administration to garner public support in an attempt to establish a state of its own under their version of “Islamic law”. Informed by the experiences of other jihadi groups and recommendations from Al Qaeda, HTS has formulated its own strategy for local governance. The approach combines positive and negative reinforcement measures, in order to secure support from the local community, through a perceived flexible administrative structure that can adapt as the situation in Syria changes. HTS poses a great danger for the stability of future Syria and the region because it seeks to establish a permanent grassroots presence through its local governance strategies—the foundation upon which to form a state—but the organization faces a number of challenges. To HTS, Local Councils are a significant asset because of the critical services they provide, even though the interests of HTS and Local Councils are often in competition. HTS also recognize that Local Councils are the official channels through which funds for aid and development will flow, both now and in the future. For these reasons, HTS pursues a relationship of mutual interest with the Local Councils. At times, HTS adopts a policy of cooperation when they are unable to take over full control; otherwise, HTS contains and infiltrates or excludes Local Councils altogether. HTS’ strategy threatens the existence of Local Councils and demands a serious effort to support these councils.

In order to maintain influence, Local Councils must effectively provide public services, gain support and legitimacy from the local communities, and institutionalize their cooperation with local forces pursuing a free and modern nation state. Furthermore, Local Councils must establish a clear and direct relationship with the Provincial Councils and the Interim Government. And, finally, Councils should attain adequate financial resources and depend less on donors. Only then will Local Councils be capable of overpowering HTS and supporting the creation of a free and modern nation state.

([1]) Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, commonly referred to as Tahrir al-Sham and abbreviated HTS.

([2]) Local Councils refers to the councils that are part of the Ministry of Local Administration under the Syrian Interim Government.

([3]) Charles Lister, Profiling Jabhat al-Nusra, Brookings, Date: July 27, 2016. Link https://goo.gl/otk0JT

([4]) JFS refers to Jabhat Fateh al Sham formed in January 2017

([5])Al Jolani outline four main goals of JFS, 1) ruling with God’s religion and establishing justice among the people, 2) uniting the forces of the mujahedeen and liberating the Levant from the regime and its allies, 3) protecting the Syrian jihad and continuing it in all legitimate ways, 4) relieving the suffering of Muslims and addressing their concerns at all costs, and 5) providing a peaceful and respectable life for people in the Islamic state. See the Announcement of JFS by Abu Muhammad Al Jolani, You Tube 07/28/2016 https://goo.gl/wDz7Os

([6]) Harakat Ahrar al Sham al Islammiya, commonly referred to as Ahrar al Sham, is a coalition of multiple Islamist and Salafist groups that joined to form a single group in 2011.

([7])Aaron Lund, The Jihadi Spiral, Carnegie Center, 02/28/2017 https://goo.gl/8ShXrp

([8])Ahmad Abazaid, The Great Competition: Ahrar Al Sham vs HTS https://goo.gl/Efr7qu

([9]) Daniel Green , Al Qaeda’s Soft Power Strategy in Yemen, The Washington Institute 01/23/2013 https://goo.gl/L8SGqq

([10])Challenges facing the local administration in Aleppo, Aljazeera, 3/31/2014, https://goo.gl/GmzdYc

([11])Announcement by the General Administration for Services/Office of the Technical Services on the Border in the Town of Harem, Official page of the Town of Harem, 04/20/2017, https://goo.gl/o8Yz6O

([12])Cooperation between the local council in Kafar Daryan with the General Administration for Services to connect an electricity line, Official page of the local council in Kafar Daryan, 10/19/2016 https://goo.gl/iOXzgP، and an electricity station in Saraqib, Radio al Kul, 2017/30/03 https://goo.gl/uO5bvg

([13])A member of the local council of the town of Sinjar mentioned that the council was structurally affiliated with the HTS controlled General Administration for Services on 05/17/2017.

([14])Structure of the Harem Town Council affiliated with the General Administration for Services, Official page of the Harem Town Council, 05/21/2016https://goo.gl/NfRXBG

([15])Maintenance work on the electricity stations in Al Zarba, Official page of the General Administration for Services. 05/01/2017 https://goo.gl/lpDP2K

([16])The Talmans Local Council President Fadel Burhan Omar said that there was a difference in the way HTS dealt with the Local Councils compared with Jabhat Al Nusra. Previously, the organization operated using military figures, but now it uses civilians. This information was gathered during an interview conducted over social media on 04/27/2017.

([17])Charles Lister, Profiling Jabhat al-Nusra, Brookings, July 27, 2016. https://goo.gl/otk0JT

([18])Information gathered through an interview conducted over social media with an individual working with civil society organizations in Idleb province on 05/22/2017.

([19]) Al Jolani’s Latest Plan: Fighting in Search of a Policy, Ahmad Abazaid, Idrak, 02/09/2017, https://goo.gl/4sTImj

([20]) HTS: Similar to Regime Prisons with Ideological Torture, Sultan Jalabi, Al Hayat, 05/13/2017, https://goo.gl/RWHsLq

([21]) Protests in Idleb in support of HTS and rejecting Astana 4, Micro Syria, 05/12/2017,https://goo.gl/cOJ6z7

([22]) Al Qaeda’s Shadow Government in Yemen, Daniel Green, Washington Institute, 12/12/2013https://goo.gl/qYjOeG

([23]) The Courts Ban the Sale of Any Real Estate Belonging to Muslims, Zaytouna Newspaper, 01/04/2017https://goo.gl/ANWN6c

([24])Yasir Abbasmay, How Al Qaeda Is Winning In Syria. War on the Rocks. 10/05/2016. https://goo.gl/kUSDvF

([25]) The Official Page of the Dawah and Guidance Office of Jabhat al 08/04/2016, https://goo.gl/JeMqU8

([26])An interview conducted via social media with Muhammad Khattab, Head of the Local Councils Administration in the Provincial Council of Idleb on 05/19/2017

([27]) Interview conducted via social media with Muhammad Salim Khudr, Local Council Member and PR Officer, 05/19/2017

([28])Naser Hazbar, former president of the Local Council in Muarat Al Noman, indicated that the council is structurally affiliated with the Interim Government and the Provincial Council in an interview via social media on 05/22/2017.

([29])The General Administration for Services is thanked for offering its support to make the water supply network operational again, Official page of the town of Kulli on Facebook, 02/21/2017 https://goo.gl/Zlaejz

([30])Said Gazoul, Sarmada Council in Idleb Pumps Water Again After Electricity Returns, SMART News, 07/21/2016, https://goo.gl/Udyai6

([31])Interview conducted via social media with Usama Hussein, former president of the local council in Saraqeb 05/21/2017

([32])Interview conducted via social media with Naser Hazbar, former president of the local council in Muarat Al Noman, 05/22/2017

([33])General Administration for Services helps the local council in Abu Thuhoor to create a garbage dump, 04/11/2017 https://goo.gl/xtIATZ

([34])In an interview conducted via social media with the former president of the local council in Saraqeb, Usama Hussein, he confirmed that a number of armed groups operated in the area, including Liwa Jabhat Thuwar Saraqeb, Ahrar al Sham, and HTS. Liwaa Jabhat Thuwar Saraqeb has been the main force since it is considered local, 05/21/2017.

([35])Naser Hazbar, former president of the local council in Muarat Al Noman, described previous Al Nusra and HTS efforts to force the locals to accept it as the main provider of services instead of the Local Council; however, the legitimacy that the council enjoyed and the support of the local civil society prevented the success of those attempts, 05/22/2017

([36])Yasir Abbasmay, How Al Qaeda Is Winning In Syria. War on the Rocks. 10/05/2016. https://goo.gl/kUSDvF

([37])Usama Hussein, former president of the local council in Saraqeb, confirmed that the Local Councils gained legitimacy by providing services, supporting civil society, and benefiting from a strong civil society movement in Saraqeb. The presence of political parties in Saraqeb also contributed to the Local Councils’ legitimacy. These were key factors in preventing HTS and other groups from interfering in council affairs, 05/21/2015

([38])Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi. Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and Civil Society in Jabal al-Summaq. Syria Comment. Date 04/04/2017. https://goo.gl/ackML9

([39])Interview conducted via social media with Fadel Burhan Omar, President of the Local Council of Talmanas, DATE

([40])Yasir Abbas. Another "State" of Hate: Al-Nusra's Quest to Establish an Islamic Emirate in the Levant. Hudson Institute, Date: 04/29/2016. https://goo.gl/NTA6Li

([41])One of the members of the local council in Kafar Tkharim indicated that if the HTS wanted to influence the council in any way, it would resort to pressuring the council to change certain decisions. The interview was conducted via social media on 04/29/2017.

([42])Meeting of the local councils in the Misni district to discuss why the water project was cancelled by HTS, Official page of Majdalia Local Council on Facebook, 04/25/2017 https://goo.gl/h5PyMF

([43]) Omar Abdul Fattah, Sinjar in Idlib: JFS detains President of the Local Council Because it Does Not Recognize His Position, 03/01/2017 https://goo.gl/6r18s0, and after HTS refused the formation of the council it chased down members of the Salqeen civilian council and detained some of them as well, 02/21/2017, https://goo.gl/e8v1wz

([44]) Omar Abdul Fattah, Sinjar in Idlib: JFS detains President of the Local Council Because It Does Not Recognize His Position, 03/01/2017 https://goo.gl/6r18s0

([45]) HTS raids homes of local council member in Salqeen and detains a few, Zaytouna Newspaper, 02/22/2017, https://goo.gl/zejypf

Geopolitical Realignments around Syria: Threats and Opportunities

Abstract: The Syrian uprising took the regional powers by surprise and was able to disrupt the regional balance of power to such an extent that the Syrian file has become a more internationalized matter than a regional one. Syria has become a fluid scene with multiple spheres of influence by countries, extremist groups, and non-state actors. The long-term goal of re-establishing peace and stability can be achieved by taking strategic steps in empowering local administration councils to gain legitimacy and provide public services including security.

Introduction

Regional and international alliances in the Middle East have shifted significantly because of the popular uprisings during the past five years. Moreover, the Syrian case is unique and complex whereby international relations theories fall short of explaining or predicting a trajectory or how relevant actors’ attitudes will shift towards the political or military tracks. Syria is at the center of a very fluid and changing multipolar international system that the region has not witnessed since the formation of colonial states over a century ago.

In addition to the resurrection of transnational movements and the increasing security threat to the sovereignty of neighboring states, new dynamics on the internal front have emerged out of the conflict. This commentary will assess opportunities and threats of the evolving alignments and provide an overview of these new dynamics with its impact on the regional balance of power.

The Construction of a Narrative

Since March 2011, the Syrian uprising has evolved through multiple phases. The first was the non-violent protests phase demanding political reforms that was responded to with brutal use of force by government security and military forces. This phase lasted for less than one year as many soldiers defected and many civilians took arms to defend their families and villages. The second phase witnessed further militarization of civilians who decided to carry arms and fight back against the aggression of regime forces towards civilian populations. During these two phases, regional countries underestimated the security risks of a spillover of violence across borders and its impact on the regional balance of power. Diplomatic action focused on containing the crisis and pressuring the regime to comply with the demands of the protestors, freeing of prisoners, and amending the constitution and several security based laws.

On the other hand, the Assad regime attempted to frame a narrative about the uprising as an “Islamist” attempt to spread terrorism, chaos and destruction to the region. Early statements and actions by the regime further emphasized a constructed notion of the uprising as a plot against stability. The regime took several steps to create the necessary dynamics for transnational radical groups (both religious and ethnic based) to expand and gain power. Domestically, it isolated certain parts of Syria, especially the countryside, away from its core interest of control and created pockets overwhelmed by administrative and security chaos within the geography of Syria where there is a “controlled anarchy”. It also amended the constitution in 2012 with minor changes, granted the Kurds citizenship rights, abolished the State Security Court system but established a special terrorism court that was used for protesters and activists. The framing of all anti-regime forces into one category as terrorists was one of the early strategies used by the regime that went unnoticed by regional and international actors. At the same time, in 2011 the regime pardoned extremist prisoners and released over 1200 Kurdish prisoners most of whom were PKK figures and leaders. Many of those released later took part in the formation of Jabhat al-Nusra, ISIS, and YPG forces respectively. This provided a vacuum of power in many regions, encouraging extremist groups to occupy these areas thus laying the legal grounds for excessive use of force in the fight against terrorism.

The third phase witnessed a higher degree of military confrontations and a quick “collapse” of the regime’s control of over 60% of Syrian territory in favor of revolutionary and opposition forces. Residents in 14 provinces established over 900 Local Administration Councils between 2012 and2013. These Councils received their mandate and legitimacy by the consensus or election of local residents and were tasked with local governance and the administration of public services. First, the Syrian National Council, then later the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces were established as the official representative of the Syrian people according to the Friends of Syria group. The regime resorted to heavy shelling, barrel bombing and even chemical weapons to keep areas outside of its control in a state of chaos and instability. This in return escalated the level of support for revolutionary forces to defend themselves and maintain the balance of power but not to expand further or end the regime totally.

During this phase, the internal fronts witnessed many victories against regime forces that was not equally reflected on the political progress of the Syria file internationally. International investment and interference in the Syrian uprising increased significantly on the political, military and humanitarian levels. It was evident that the breakdown of the Syrian regime during this phase would threaten the status quo of the international balance of power scheme that has been contained through a complex set of relations. International diplomacy used soft power as well as proxy actors to counter potential threats posed by the shifting of power in Syria. Extremist forces such as Jabhat al-Nusra, YPG and ISIS had not yet gained momentum or consolidated territories during this phase. The strategy used during this phase by international actors was to contain the instability and security risk within the borders and prevent a regional conflict spill over, as well as prevent the victory of any internal actor. This strategy is evident in the UN Security Council Resolution 2042 in April 2012, followed by UNSCR 2043, which call for sending in international observers, and ending with the Geneva Communique of June 2012. The Geneva Communique had the least support from regional and international actors and Syrian actors were not invited to that meeting. It can be said that the heightened level of competition between regional and international actors during this phase negatively affected the overall scene and created a vacuum of authority that was further exploited by ISIS and YPG forces to establish their dream states respectively and threaten regional countries’ security.

The fourth phase began after the chemical attack by the regime in August of 2013 where 1,429 victims died in Eastern Damascus. This phase can be characterized as a retreat by revolutionary military forces and an expansion and rise of transnational extremist groups. The event of the chemical attack was a very pivotal moment politically because it sent a strong message from the international actors to the regional actors as well as Syrian actors that the previous victories by revolutionary forces could not be tolerated as they threatened the balance of power. Diplomatic talks resulted in the Russian-US agreement whereby the regime signed the international agreement and handed over its chemical weapons through an internationally administered process. This event was pivotal as it signified a shift on the part of the US away from its “Red Line” in favor of the Russian-Iranian alignment, which perhaps was their first public assertion of hegemony over Syria. The Russian move prevented the regime’s collapse and removed the possibility of any direct military intervention by the United States. It is at this point that regional actors such as Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia began to strongly promote a no-fly zone or a ‘safe zone’ for Syrians in the North of Syria. During this time, international actors pushed for the first round of the Geneva talks in January 2014, thus giving the Assad regime the chance to regain its international legitimacy. Iran increased its military support to all of Hezbollah and over 13 sectarian militias that entered Syria with the objective of regaining strategic locations from the opposition.

The lack of action by the international community towards the unprecedented atrocities committed by the Syrian regime, along with the administrative and military instability in liberated areas created the atmosphere for cross-border terrorist groups to increase their mobilization levels and enter the scene as influential actors. ISIS began gaining momentum and took control over Raqqa and Deir Azzour, parts of Hasaka, and Iraq. On September 10, 2014, President Obama announced the formation of a broad international coalition to fight ISIS. Russia waited on the US-led coalition for one year before announcing its alliance to fight terrorism known as 4+1 (Russia, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Hezbollah) in September 2015. The Russian announcement came at the same time as ground troops and systematic air operations were being conducted by the Russian armed forces in Syria. In December 2015, Saudi Arabia announced the formation of an “Islamic Coalition” of 34 largely Muslim nations to fight terrorism, though not limited to ISIS.