Rateb

The Security Scene in Sweida: Context and Expected Outcomes

After being accused of kidnappings, the regime-backed Fajer militia experienced wide-scale hostility from local Sweida groups and had their headquarters seized. This may signal growing discontent with the Syrian regime's role in Sweida's deterioration.

Background

Located in southwest Syria and home to over half a million people, Sweida province has become a refuge for internally displaced persons and its host population. Sweida is predominately composed of those who identify as Druze. Their religious and ethnic identity fueled their strong inter-community tie and unified front prior to 2011. In 2011, a visible divide surfaced in Sweida between those who remained loyal to the regime, those who supported the protest, and those who wished to keep the province neutral. The Syrian regime capitalized on the growing fear, proclaiming that only the Syrian regime could protect the Druze community from the majority takeover. Although a divide in political perspective exists, the tensions between the community in Sweida subsided.

Although the formal administrative governance structures are affiliated with the Syrian regime, the community has maintained partial independence. Unwilling and unable to open another battlefront, the Syrian regime has mitigated incidents to prevent growing opposition in the Druze community. Most Druze religious leaders guided the community towards a more neutral position to maintain ties and stability. Although some in Sweida prefer to remain in opposition to the regime or neutral, there are also those that actively proclaimed their loyalty to the Syrian regime, such as the notorious colonel Issam Zaher Eddin(2) or in establishing an independent militia, such as "Fajer(3)"

Sweida's demographic composition has allowed it to retain partial independence from the Syrian regime. Given Sweida's unique ethnic, religious and political dynamics, the Syrian regime has granted it partial independence. Among the oral agreements with the Syrian regime, is the halt to military conscription. Although unannounced and not formally publicized, young men in Sweida are not forcefully detained and conscripted. This compulsory military service requirement is implemented diligently in all other regime-controlled regions. This means that men in Sweida, as long as they are confined to the province's borders, will not be actively hunted and forced to battle fronts. This does not mean the regime has not tried to pressured men from Sweida to join the military.

In negotiations with Sweida leaders, Russia, on multiple occasions, has presented the Dara'a scenario(4) to support regime military operations in the south, but the people of Sweida have been able to refuse with little repercussions. The hesitation by the Syrian regime to act directly and aggressively in the province, has also allowed citizens in opposition some freedom to express dissent. This includes protests, establishing civil society organizations, and relief non-profits.

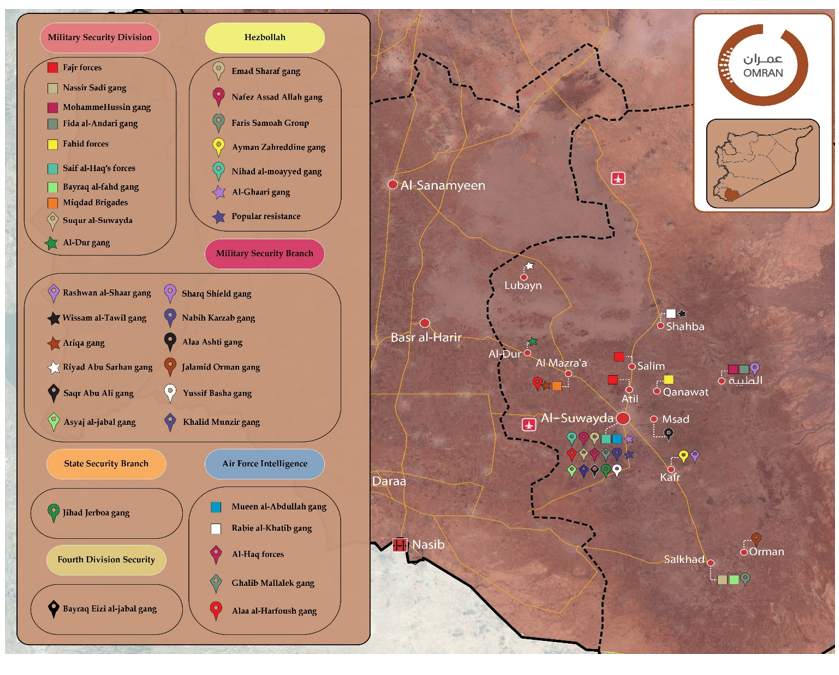

Although Sweida is a unique situation with partial independence, Syrian regime security remains widely present. The regime supported several loyal but independent militias and fueled the intelligence apparatus, and its leader Kifah Millhem(5) to continue surveillance of the region.

Recent widespread anti-regime sentiment in Sweida province has begun to unravel. The most recent revolt occurred in July 2022, the Druze leaders called for unity and attempted to expel the regime loyal, and Iran-backed, Fajer militia after suspicion of kidnapping civilians. Several of Sweida's local military groups united in 2018 under the name "Asharayan Alawhad" to maintain security. Iran-backed forces targeted this group through assassinations.

Residents of Sweida were already facing increased pressure due to the deteriorating economic and security situation, and local armed groups decided to react to Fajer militias' latest violation. After clashes and multiple deaths, the local groups that opposed Fajer surrounded their headquarters. Although Russia attempted to intervene, local groups claimed it was an internal issue and proceeded to its intensive response to Fajer militia's actions. Such resistance by local groups in Sweida may escalate, as tensions continue to rise from the economic and security deterioration.

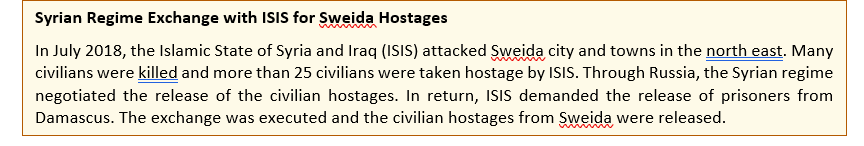

Negotiations are expected with Russia's help to subside the recent tensions. It is expected that the Syrian regime and Russia will intervene to decrease tensions from rising in south Syria. Similar interventions occurred during a prisoner exchange with ISIS in July 2018. Tensions rose in Sweida, as they believed the regime was purposefully exposing them to ISIS attacks. To maintain the peace, the regime completed a prisoner exchange with ISIS to release civilian hostages from Sweida.

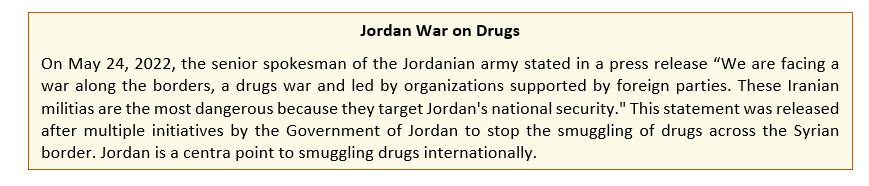

Drug trafficking in Sweida is a noteworthy contributor to rising resident opposition to Iran and regime-backed groups. Sweida has become a central region for Hezbollah and Iran to grow and trade drugs, with an intricate network internationally. According to in-depth reports completed by COAR Global(6) captagon(7) exports from reached a market value of 3.46 billion USD. Multiple local news outlets(8) in Sweida have reported on the drug crisis in the province, highlighting the many drug workshops present to produce captagon. Civilians from Sweida are recruited to work in the drug workshops, and a portion of the profits go to the Iran and regime backed militias to fund arms and vehicles. The Government of Jordan recently released a statement declaring war on drugs, showcasing the growing problem in the region.

Appendix A:

([1]) Original paper published on August 8, 2022, in Arabic, https://bit.ly/3wtvLaD

([2])Issam Zaher Eddin, originally Druze from Sweida, was appointed as a major general in the Syria Republic Guard. He played a major role leading many regime offensives.

([3])A regime loyalist militia group that is backed by Iran and is accused of abducting and sparking clashes with local groups.

([4]) In the Dara’a scenario, after regime invaded and conquered the territory from the opposition in 2018, Russia proposed an alternative to the security structure. Instead of forcefully conscripting the young men in the region to join regime military and battle fronts, Dara’a created its own military group “5th Falaq group” to support regime security.

([5]) Appointed in March 2019, Kifah Millhem was appointed by the Bashar Al-Assad as the new chief of the Military Intelligence Directorate. He is suspected to be responsible for the deaths of thousands and a war criminal.

([6]) https://coar-global.org/2021/04/27/the-syrian-economy-at-war-captagon-hashish-and-the-syrian-narco-state/

([7]) Captagon is a manufactured drug that acts as an alternative to amphetamine and methamphetamine

([8])الجيش الأردني يقتل 4 أشخاص ويحبط تهريب كميات مخدرات كبيرة آتية من سوريا, 2022 May 22, https://www.alquds.co.uk/الجيش- الأردني- يقتل -4- أشخاص

Governance in Post-2011 Syria: Challenges & Opportunities

Omran Center for Strategic Studies, Istanbul Medipol University Center for Mediterranean Studies (AKAM) and Black Sea Strategic Research Association (KASAM) are pleased to announce the international conference titled “Governance in Post-2011 Syria: Challenges & Opportunities” which will take place at Istanbul Medipol University, November 15, 2022. The conference will shed light on the reality of governance and its emerging models in Syria, in addition to addressing the changing dynamics and their future repercussions on the country under the current conflict conditions.

We will be accepting proposal submissions in English, Arabic and Turkish until September 10, 2022.

For more details:

Proposal form link:https://bit.ly/3S2y9i2

Participation standards and required conditions: https://bit.ly/3BagD5u

Anuual Report 2021

Established in 2013 in Turkey with presence in Syria, and an office in Washington, DC.

Publishes in-depth studies, analytical maps, and policy recommendations on Syrian and regional security, politics, economics, and local governance.

Hosts conferences, workshops, and seminars, bringing together scholars from around the world.

Omran's Impact

Through continuous engagement with public opinion and decision makers, providing a range of solutions and policies that drive political change and stability.

Social Engagement

- Reaching approximately 732.409 people interested in Syrian affairs on social media platforms.

- Interacting with 44 local, regional and international media outlets to inform the public on Syrian affairs.

- 26 institutions have republished Omran’s work as a major source of information.

- 12,047 people engaged in meetings and dialogues

- 12 agencies republished outputs of Omran, while 31 local and international institutions relied on the center’s outputs as a main source for their published materials.

- 109 field meetings and activities inside Syria with local activists, including Ihsan’s protection centers, Local Councils and Chambers of Commerce and Industry.

- 40 local, regional, and international media organizations engaged with the aim of informing the public on the developments and events of the Syrian issue.

Engagement with Decision Makers

- 61 events with local activist's networks, Syrian NGOs, civil society organizations, lawyers, military experts, and scholars.

- 28 research meetings with Arab and international research centers and think tanks.

- 117 meetings/events with representatives of local, regional, and international states and political figures.

Research Collaboration

- 28 research products published by Arab and international intellectual institutions.

- 18 research consultations for researchers and students working on Syria.

- 66 workshops in collaboration with research centers, institutions, and other parties.

Dr. Ammar Kahf | How important is the conflict in Syria to the EU?

Dr. Ammar Kahf, executive director of the Omran Center for Strategic Studies, commented on the Brussels donor conference, saying, "The pledges were better than expected, except that the focus was always on the aid approach rather than the systematic empowerment approach that the Syrian people need to create more jobs.

For More: https://bit.ly/39vJMvY

Normalizing with the Assad regime, Different Approaches at Different Levels

From the beginning of the Syrian uprising, several Arab countries were almost unanimous in isolating the Syrian regime to punish it for its violations of Arab League resolutions and the rights of the Syrian people. This approach was translated by Qatar’s leadership in the Arab League and the important support of Saudi Arabia and post-revolutionary Tunisia and Egypt into a resolution that led to the suspension of the regime’s membership in the Arab League in November 2011.

In the following years, most Arab countries called on the regime to stop military operations against civilians, and some of them even played a greater rolein actively seeking regime change in diplomatic manners and by supporting and financing the opposition. However, in the coming years, political changes occurred in some Arab countries such as in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, causing a departure from regime change politics to the restoration of pre-Arab spring MENA security order, thus affecting the regional attitude towards the Syrian regime.

Egypt resumed consular relations in 2013, when most Arab countries took a stand against the Syrian regime, but has not fully normalized its relations with the regime to date. This shows that Egypt prioritizes the stability of the Syrian regime in its foreign policy, as Egypt distrusts the opposition and considers it a proxy for Turkey. Moreover, Egypt prefers to work with the army and considers it more reliable.

The UAE and Jordan, on the other hand, were on the opposite side and supported the Syrian opposition to varying degrees, but after the Russian intervention in 2015, the situation on the ground had changed, which, along with other factors such as the UAE’s attempt to counter Turkey and contain Iran with a different approach in Syria, led to a change in the countries’ priorities in their foreign policy toward Syria. In 2018, the UAE and Bahrain reopened their embassy in Damascus and resumed relations with the Syrian regime. The UAE wants to normalize its relations with the Syrian regime in order to have relations with all parties on the ground.

Similarly, when the Syrian opposition lost control of southern Syria in 2018 and signed reconciliation agreements, Jordan reopened its border with Syria with some restrictions, as it had done before 2015, Jordan has not completely severed relations with the Syrian regime, but it has downgraded its representation. It normalized its relations only in October 2021 after a telephone conversation between King Abdullah and Bashar al-Assad, which was expected after King Abdullah’s speech on CNN during his visit to Washington and after his meeting with President Biden.

Looking at the factors behind this action, the first one seems to be the economic factor, because the country is in a difficult economic situation, aiming at normalization and cross-border trade, as the Arab gas pipeline will help the Kingdom’s economy. In addition, the security factor is not as important as the economy, but it plays a role because the Kingdom is concerned about stability on its northern border and normalization will help in security coordination with the Syrian regime to prevent possible threats.

2021, the beginning to regime regional re-integration

In the last quarter of 2021, more precisely on November 9, 2021, the Foreign Minister of the United Arab Emirates, Abdullah bin Zayed, visited Damascus as the highest UAE official since the beginning of the Syrian uprising in 2011. The visit came at a time when the idea of normalizing relations between Arab countries was discussed among Arab officials, and some expressed this on various occasions. In addition, Jordan’s King Abdullah spoke to Bashar al-Assad by phone in October last year, removing doubts about relations between the two countries.

At the same time, Egypt, which has maintained close relations with the Syrian regime in recent years, has not yet fully normalized its relations. So, if we look at the approach of each country, we can examine the differences between these three actors in the region-Egypt and the UAE, Jordan-in terms of timing and level, as well as their advocacy for the Syrian regime. Timing shows how long these countries have been linked to the regime, while level shows how deep these links are. Advocacy shows which countries are committed to the regime’s return to the Arab world.

As for the level, not all countries that normalize with the regime do so to the same degree. Egypt has played a role in supporting the Syrian regime, although it has not yet fully restored its relations with the country. There are several reasons for this, such as the desire to maintain relations with the Gulf States, as they have led the front against the Assad regime.

Egypt’s main objective is to view this relationship from a political and security perspective. The UAE, on the other hand, is looking at the relationship from an economic and political perspective. They want to participate in the reconstruction process in the coming years. Therefore, its normalization process with the Syrian regime has taken place without any conditions.

Although it has not severed its relations with the regime, Jordan has taken positions close to the Syrian opposition over the past decade, but has kept its border open with the Syrian regime for economic reasons. The Kingdom believes that normalizing its relations with the regime will help its economy recover and that it wants to play a role in resolving the conflict. Jordan has also sought to reactivate the bilateral agreement with Syria on various issues such as water. It also wanted to reactivate the Arab Gas Pipeline to reach Lebanon through Syria, which is part of the kingdom’s ambitions to become an energy hub in the region.

What sets Jordan apart, however, is that it is not only Jordan that wants to engage with the regime, but also brings along other countries that have the same idea of changing the regime’s behavior through concessions and vice versa. It is an approach that has met with the approval of the Biden administration. As part of its strategy to manage the Syria conflict by focusing on changing the regime’s behavior rather than regime change, this administration’s new approach to Syria is the opposite of the previous administration, which pursued a policy of maximum pressure.

In March 2022, another important UAE rapprochement with the Syrian regime took place, namely Bashar al-Assad’s visit to the country. This visit is considered very significant, mainly because it was al-Assad’s first visit to an Arab country since the beginning of the uprising. The visit can be analyzed from various points of view, such as future investments, the possibility of the regime’s return to the Arab League, and Iran’s influence.

The possibilities of reinstating the Syrian regime in the Arab League

In terms of support for the Syrian regime, not all of these countries are equally committed to Syria’s return to the Arab League in order to normalize the country’s relations with the world, but we can see some differences. In late January this year, Arab League Secretary General Ahmed Aboul Gheit said that Syria’s return to the Arab League was not discussed at the consultative meeting of Arab foreign ministers in Kuwait. He later added that Syria’s return to the Arab League depends on consensus among Arab countries. These are indications that a return is unlikely at the next summit.

The irony is that Egypt is playing a role in the Syrian regime’s return to the Arab League but has not yet fully normalized its relations with the Asaad regime, which could happen in the near future. As mentioned earlier, Egypt sided with the Syrian regime under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, and the two countries have since restored consular relations.

The UAE changed its stance on Syria after 2015 until it normalized its relations with the regime. After that, they began to support the Assad regime and promote the normalization of their relations with other countries in the region. They went even further by calling for the lifting of sanctions imposed on Syria.

In Jordan, however, we see a different approach that accepts the current status quo in Syria as a reality. For example, Jordan does not fully side with the regime in the Syrian conflict, but rather seeks to benefit from the opening of its relations with the Syrian regime on an economic level and restore the situation to what was before the border between the two countries. In doing so, it advocates its approach to Syria “step by step” as a comprehensive plan for dealing with the regime.

Ultimately, these approaches are similar in some respects, but they are not identical. This means that not all of the approaches these countries are taking have the same goals. Moreover, not all countries approaching the Syrian regime can be considered allies of the regime; rather, it is about their needs.

Finally, these approaches are similar in some respects, but they are not identical. This raises the question of which of these approaches will be successful and how this will affect the situation on the ground. To what extent these approaches will be able to bring the Syrian regime back to the Arab League.

So far, these approaches have not been able to change the position of Riyadh and Doha in terms of normalizing relations with the Syrian regime, which may show how effective these processes have been so far. On another level, will the relations between the Syrian regime and the international community remain the same? Will we see some changes in the position of some countries like the U.S., or could other approaches be taken?

The Autonomous Administration: A Judicial Approach to Understanding the Model and Experience

As the central state authority declined, in favor of the emergence of sub-state formations including ethnic and religious ones, along with international and regional interventions, several local governance models have emerged across Syria as reflected by the dynamic military map. This led to the disappearance of some models and the decline of others, whereas other models achieved relative and cautious stability. In this regard, the “Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria” falls within the last category as it developed through several phases until it reached its current model. Although many years have passed since the actual declaration of the Autonomous Administration with its various institutions and bodies, the level of governance and nature of administration in these institutions and bodies remain problematic and questionable. Thus, this study seeks to explore the nature of the administration and the level of governance in this developing model using the judicial authority as an entry point, as it is considered one of the most prominent indicators. The impact of court processes is not limited to the judicial field, nor does it reflect the legal interest alone; it also offers several indicators on the political, administrative, security, economic, and social levels. Therefore, the study examines the judiciary system of the AA, its structure, various institutions, legal foundations, in addition to the employees working in and running those institutions and their qualifications. The study also attempts to explore the effectiveness, efficiency, and working mechanisms of this system, as well as its impact on North-Eastern Syria, in addition to the complex problems in that region (political, tribal, ethnic and “terrorism”).

Establishing a National Farmers’ Association (NFA) in Opposition- Held Areas

Introduction

In opposition-held territories, the agricultural sector suffers from a variety of complex challenges. Among those challenges is that supply exceeds demand due to poor planning, absence of refrigerated storage facilities, weak purchasing power, absence -or limited- presence of food production factories, and the absence of export channels. Although some exports have moved from Syria to Turkey, they remain limited in quantity and continuity. Most sellers were left with no choice but to sell their products at unfairly low prices, with a high cost of production and export logistics, leaving them with little if any margins of profit. Such challenges have prevented agricultural production from employing the necessary workforce and strengthening the food cycle throughout the years. The current governance dynamics prevents farmers from securing effective solutions, and therefore the farming community continues to endure losses. This has drastically affected the development of the agricultural sector within these regions.

The following paper covers some of the agricultural sector's challenges and proposes recommendations to empower its sustainable growth. The outlined recommendations may offer some solutions to achieve the minimum level of recovery of costs and create a plan of action.

Accumulated Challenges

The problems faced by the agricultural sector, whether in terms of supply or demand, can be summarized as follows:

Governing bodiesignored the calculations of the absorptive market capacity (demand) of agricultural crops, which increased the financial losses and caused a weak valuation of the sector. For example, based on a 2020 study by the General Organization of the Seed, for onions and potatoes crops, the General Organization for Seed Multiplication estimated the surplus local onions production at 25% and local production of potatoes at 19%. The percentage was estimated without considering the worker's wages, as farmer hardly earns $100 per hectare of onions, while their loss is $1,668 per hectare of potatoes.

In addition to inaccurate calculations, farmers also endure difficulties in exporting produce. Exporting agricultural products from opposition areas to regime-held districts is neither easy nor feasible because of the high transportation costs and bribes to guards at regime-held checkpoints. For example, a kilo of onions in al-Bab area is estimated at the writing of this paper at 200 Syrian Pounds but reaches 500 S.P in Damascus' markets(1) There are also high costs and difficulties in exporting produce from opposition-held territory to Turkey. In June 2018, the opposition areas exported only 4,000 tons of potatoes to Turkey, even though the local production of potatoes was around one million tons. Among the difficulties is the local council’s low capacity to facilitate exports with Turkey. Usually, Turkish authorities show interest in importing commodities from the opposition area, requesting lentils, chickpeas, pistachios, pomegranates, cherries, potatoes and onions, according to their needs in cooperation and coordination with local councilswho mediate between the Turkish government and local Syrian fermers(2)

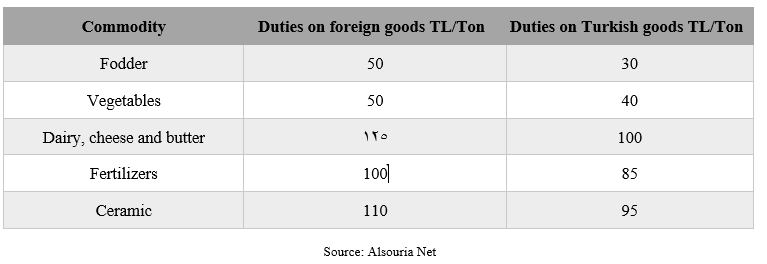

Furthermore, current procedures implemented by Syrian Interim Government do not accurately facilitate the market balance between goods imported from abroad and those produced locally. This leads to the dumping of produce by the local market due to imported items creating a surplus in the market. This became relatively frequent after March 2021, when the Syrian Interim Government reduced customs costs for Turkish goods entering the areas of Aleppo countryside through the Al-Salama, Al-Ra'i, Jarablus, Al-Hamam, Tal Abyad and Ras Al-Ain crossings, as the following table shows(3)

It is evident that the agricultural sector is suffering for a multitude of other reasons. These reasons include the negative impact of the industrial sector, high costs of raw material, lack of accessibility to energy sources such as water, electricity, and fuel, the low purchasing power of citizens, and the unstable security environment. Water has become an issue across the region, but Al-Bab in particular, has suffered from lack of water due to the digging of random wells and draining of the strategic water reserves.

Establishing a National Farmers’ Association (NFA) as a First Step

In order to understand the issues and minimize its negative impacts, there needs to be direct communication and support with non-governmental civil bodies in the agricultural sector. Among those bodies are farmer cooperatives. Communication with both official and non-official institutions to create a strategic plan to regulate agricultural production would achieve national interests and local production and agricultural capital sustainability. To achieve that, the area may establish a National Farmers’ Association (NFA) as a non-profit, non-governmental, agricultural association that brings together local farmers’ associations and agricultural societies and unions scattered in the region outside the government control. The NFA would employ experts and build communication networks across institutions and organizations, such as the Directorate of Agriculture in the Syrian Interim Government, the Organization for Seed Multiplication, local councils, and the Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry, and relieforganizations. It will also be tasked to develop an integrated plan to help such institutions to better manage the agricultural sector in terms of quantity and quality, supply and demand while adopting a trademark for local agricultural crops, health specifications, and quality management that conform to international standards.

To enhance communications, the NFA may issue quarterly reports that include an economic index to measure the growth of the agricultural sector to enhance the values of transparency.

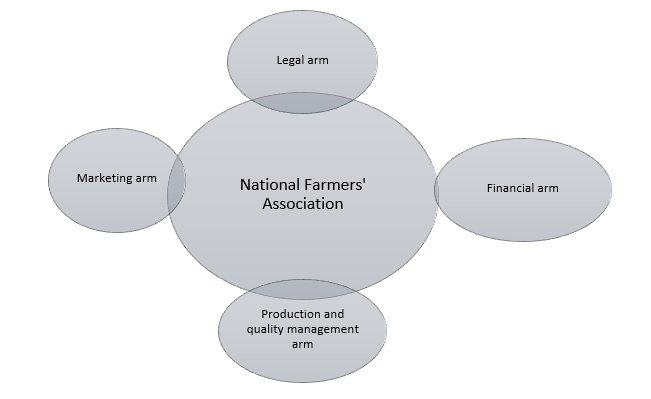

As shown in the figure below, the NFA would be a public body comprised of farmer unions/ associations from every city and town who select a national entity. This new entity would then establish the supporting offices that include: (1) a Legal Office to consider the affairs of agricultural licenses and property rights, control the investment process, issue instruments, and control violations. (2) Marketing Office promotes products and projects to investors and investment entities, negotiates with governments, and signs memorandums of understanding and work protocols to promote agricultural crops and secure consumption channels. (3) Production Management Office that will adapt the production plan to the market needs of food, industry, storage, export and other needs, (4) Financial Office that will be responsible for the transactions, financial liquidity, and the funding and crediting process.

The NFA can preliminarily work in four tracks:

A. Trademarking for Syrian Agriculture

This track includes structuring the agricultural process as a whole and attaining a certificate of confidence from farmers in their willingness to work with the NFA. This process will allow farmers to be included in a registry that will be followed up with regularly.

The other step is to stamp the crop with the NFA's “stamp” to indicate that the product conforms to international health and agricultural specifications. This will enhance the NFA’s control and trust in Syrian communities and abroad. These two steps will motivate the farmer to return to his land and gain greater confidence in both his/her work and product.

B. Regulation of the production process

The failure to consider the balance between supply and demand has led significant increases or decreases in prices. The NFA would intervene to advance the calculations around production to determine the quantity of production, demand, and whether consumption, manufacturing, or exporting, are the necessary response. Through these proper calculations, the NFA would be better able to manage the production process costs and prevent financial losses for farmers eventually.

C. Policy Recommendations to Local and International Actors

Through its reach and capacity, the NFA will be able to issue recommendations on the agricultural sector in Syria to key stakeholders. The NFA would submit recommendations to the Syrian Interim Government, communicating them to relevant governance bodies. This will help enact protectionist policies that limit the import of any product similar to the specifications of the local one, thus reducing the dumping of local produce and harm to farmers. Recommendations may include imposing taxes and duties on every imported product similar to the local product. This will protect the local product, raise its competitiveness, and diversify markets.

D. Product Marketing

For the marketing process, the NFA should focus on two aspects: (1) the legal basis of contracts and covenants for agreements between two parties. The agreement documents will be in accordance with the international legal framework, and (2)the NFA will strengthen the assets of power and negotiation with Turkey on imports and exports to and from opposition areas, including the transit of local products through Turkey’s territory for exports abroad.

E.Developing the Finances surrounding the Agricultural Sector

The lack of financial institutions, such as banks, in opposition areas, has contributed to decreased sources of credit and created a fragile environment for funding and payments. The exchange rate and prices are constantly fluctuating. The NFA can design a financial program that regulates the credit and funding process based on the environment and situation. This includes signing work protocols with organizations, companies and banks, opening bank credits in Turkey and other countries to facilitate the payment and receipt process, and issuing special farming financial instruments(4) to be sold to Syrian investors at home and abroad with the guarantee of the NFA. The NFA can also direct funds to support the food industries sector and various industries in the agricultural sector.

Conclusion

Although establishing a new body is difficult for the local community, it is fairly necessary. The costs of establishing the NFA is minimal compared to the depletion witnessed by Syria’s agricultural sector. The region will reap the fruits of this work, not only by finding nearby and far markets for selling products but also by increasing confidence in the Syrian product, organizing the production process of agriculture, funding food facilities and factories, enhancing the local supply chain, and finally pushing the process of early economic recovery forward. This will present an opposition governance model capable of creating “stability” within a particular aspect

([1]) The farmer sells a kilo of onions for 200 pounds, and the cost of transporting it to Damascus is 300 pounds, Syria TV, 26-01-2021, link: https://bit.ly/3CSLdyA

([2]) Turkey starts importing potato from war-torn Syria, 27-6-2018, link: https://cutt.ly/zRC8lhw

([3]) “The Interim Government” announces a reduction of customs duties of Turkish goods, Alsouria Net website: 14-03-2021, link: https://cutt.ly/XRC3zs3

([4]) Sukuk: Securities from the Islamic Sharia-compliant financing tools. The instrument is linked to specific projects and investment opportunities that are already existed or under construction. The instrument is equal to the value of a share in an ownership, and the holder of the instrument takes profits and has the right to participate in the management, capital, and trading. There are many types of instruments in Islamic Sharia, known as Sukuk (instruments),such as al-Mudaraba, al-Murabaha, al-Istisna’a, al-Musakah, al-Muzara’a, Ijara, services, and others.

The Chain of Command in the Syrian Military: Formal and Informal Tracks

Executive Summary

- This paper provides an illustrative overview and assessment of the chain of command inside the Syrian Military and Armed Forces, while also noting the impact of both formal and informal tracks. It also explains the impact of the regime’s allies intervention in military decision making.

- Interactive figures visualize the decision-making lines within the chain of command, illustrating who occupies the most critical positions in the army, security services, and the Syrian Ministry of Interior. It also presents identification cards of the most influential leaders within that chain.

- Military and security decision-making within the regime’s structures is an ambiguous and complex process. All powers belong to the “President of the Republic,” yet the structure consolidates elements of sectarian fanaticism, security arrangements and façade, and allies’ military interventions in appointments, structures and roles.

- The regime’s complex nature allows for familial and sectarian fanaticism to intervene with the security structure. This has allowed for the bypassing the formal chain of command and the bureaucratic mechanism. The flow of commands then favors many loyalties and those connected.

- The military intervention of the regime’s allies, particularly Russia and Iran, has impacted the Syrian military and security’s chain of command. The regime’s allies have been able to influence decision making through formal tracks and unofficial networks.

- The chain of command within the Syrian armed forces are divided into several levels, starting with the Commander in Chief, the Minister of Defense, the National Security Bureau, Intelligence, the Ministry of Interior, and then the military units.

- Despite the growing Iranian and Russian influence on the military and security institutions, Bashar al-Assad, as the “President of the Republic and Supreme Commander of the Army and Armed Forces,” still formally controls the chain of command and the flow of orders.

- The Chief of Staff position has been vacant since 2018, which is a precedent that the Syrian army has not witnessed since its establishment. This vacancy raises questions on the impact of an allies intervention and overruling over the chain of command within Syrian military institutions.

Introduction

When Syria’s popular protests sparked in 2011, the Syrian regime quickly used the military to suppress demonstrations initially and then confront the armed opposition fighters. This prolonged the military conflict and directly impacted the human resources of many military units. Military units suffered from defections, escape, non-joining, and the killing, wounding, and capturing of many soldiers. As a result of the successive military operations by opposition fighters in the early years of the revolution, the army also struggled on a logistical level, with equipment and its headquarters became strained. The military units were also affected by the redeployment operations carried out by the regime. The redeployment operations re-organized the regime’s military units, moving them from their original base location to other districts within Syria. This prompted the establishment of new formations by including units of different subordination within a new military body or unit.

On the other hand, the regime’s allies, Russia and Iran, were able to influence the general structure of the army and armed forces to varying degrees after their direct military intervention. For example, Iran formed militias outside the military structure and later incorporated relatively small local militias within military divisions giving Iran military influence within the ranks of the Syrian military. On the other hand, the Russian intervention had a more significant and more profound impact. Moscow supervised the training, armament, and development of military plans for most army units and formations, restructured some military units, and founded new military formations that are linked to Russia directly.

The mentionedchanges led to transformation in the army’s structure and power nodes, directly affecting the chain of command and the military hierarchy for orders within official or unofficial networks.

This paper seeks to shed light on the chain of command and decision making flow within official and unofficial networks, with a focus on the regime’s allies influence on the Syrian military institution as a whole. The “interactive figure” illustrates the path of commands through the Syrian military structure within theessential positions in the army, security services, and the interior ministry. The “interactive figure” also provides identification cards for the leaders of these units, and uncovers the subordination of each unit within the chain of command and orders.

Supreme Commander of the Army and Armed Forces

As “President of the Republic and Supreme Commander of the Army and Armed Forces” per Article /105/ of the 2012 Constitution, Bashar al-Assad is the anchor point, the beginning of the chain of command, and the source of official orders. The Minister of Defense, General Ali Abdullah Ayoub, the Head of the National Security Bureau, Major General Ali Mamlouk, and the Minister of Interior, Major General Muhammad Rahmoun, are linked to him directly.

All appointments and promotions of commanders, directors, chiefs, and officers of all army and armed forces units, including the security services, are carried out through decrees and decisions issued personally by Bashar al-Assad. This happens at two levels: first, a routine bureaucratic level represented in issuing periodic promotions, transfers, and appointments according to the chain of command and official orders, and by consulting the National Security Bureau and the intelligence services, each according to its competence without any interference by the civil state agencies and institutions. The second level is through managing the equilibriums of the relationship with the regime’s allies and making appointments that take these relationships into account.

Although the decision-making mechanisms and hierarchy are clearly outlined, they are not binding for Assad to follow. He exceeds the issuing orders of any party, assisted by a broad power afforded to him by the constitution and laws regulating the army’s work. Additionally, the complex nature and structure of the regime (security, family, and sectarian considerations) often makes the decision-making mechanism a highly ambiguous process.

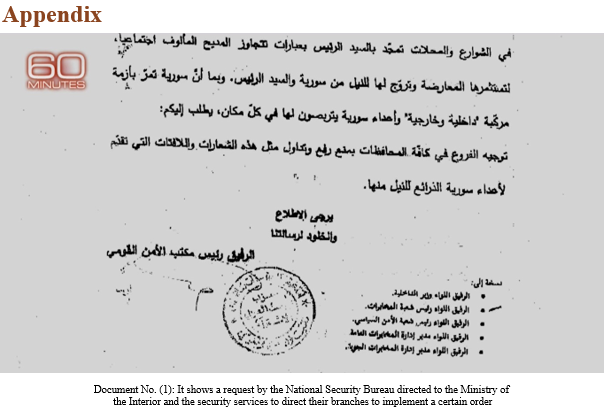

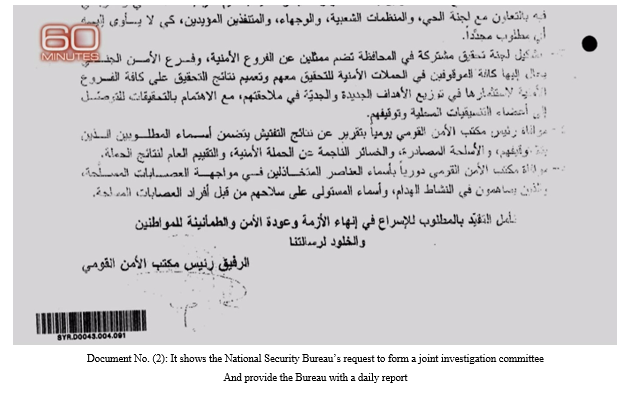

National Security Bureau and Intelligence Services

The National Security Bureau, headed by Major General Ali Mamlouk since July 2012, serves as the primary hub that links, supervises, coordinates, and directs the work of security.The Bureau holds a critical advisory role to Bashar al-Assad in all issues related to national security, negotiations, and other internal and external security affairs. Four main security agencies operate under its advisory with their various subordination; the Military Intelligence Division, Air Force Intelligence Department, General Intelligence Directorate, and Political Security Division.

The Military Intelligence Division reports directly to the General Staff, while the Air Force Intelligence Department belongs administratively to the Air Force and Air Defense Command. These two agencies are the largest and most powerful intelligence agencies that belong “officially” to the Ministry of Defense. On the other hand, the General Intelligence Directorate, also known as “State Security,” reports directly to the President of the Republic. The General Intelligence Directorate coordinates directly with the National Security Bureau. In terms of the Political Security Division, it belongs administratively to the Ministry of Interior. Nevertheless, the Minister of Interior does not have any actual powers over the Political Security Division’s work, and only coordinates its administrative and logistical aspects. Instead, the Political Security Division is the one that monitors the entire Ministry of Interior, starting with the Minister of Interior and ending with the ministry’s most minor elements.

The heads of the four security agencies and their branches are appointed personally by the President of the Republic, without any interference by the civil state institutions or even informing them. The commanders of the Military and Air Intelligence agencies must be from the army’s ranks. As for the leaders of the General Intelligence and Political Security agencies, some of them may be secondment to the Ministry of Defense or the Ministry of Interior, in order to work in these agencies, which applies to all officers working in the intelligence services.

Currently, major generals that lead these four offices are; Kifah Melhem, Head of the Military Intelligence Division, Ghassan Ismail, Head of the Air Force Intelligence Department; Hussam Louka, Head of the General Intelligence Directorate; and Ghaith Deeb, Head of the Political Security Division. All of them are Military College graduates. Since their establishment in the 1970s (in their current form), the Military and Air Intelligence Agencies have been headed by officers from the Alawite sect, while officers in the General Intelligence and Political Security may be from other sects.

Ministry of Defense

Since the beginning of 2018, the Ministry of Defense has been led by General Ali Abdullah Ayoub, a successor to General Fahd Jassim Al-Freij. The Minister of Defense is appointed by the President of the Republic and Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Armed Forces. The prime minister never interferes in this process. The Minister of Defense holds the position of Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Armed Forces, as a Deputy Prime Minister, and a member of the Central Command and the Central Committee of the ruling Baath Party. The Ministry of Defense mainly supervises the General Staff and several offices and departments affiliated with it. It also coordinates with the ministries and state institutions on the affairs of the army and the armed forces in the aspects that require coordination.

General Staff

The Chief of the General Staff of the Army and Armed Forces is usually occupied by the rank “General” and is appointed by the President of the Republic and Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Armed Forces. The Chief of Staff is also treated as a minister by the Military Service Law of 2003 and its amendments. He is the officer who controls the Ministry of Defense at a later time. This is a common trend, as all defense ministers since 1967 served as chiefs of the General Staff, before pursuing Minister of Defense.

Since July 2012, General Ali Ayoub had held the position of Chief of Staff, but was later named Minister of Defense at the beginning of 2018. Since then, the position of Chief of Staff has remained vacant. This is an extraordinary situation that the Syrian army has not witnessed since its establishment in 1946,which raises many questions about how military operations are managed throughout the country during a “war.” Currently a chief of staff is not present to manage those operations. Sources indicate that the Russians (and Iranians) have assumed tasks related to the chief of staff in military operations through the Russian operations room located in Damascus (in the headquarters of the General Staff).The Minister of Defense assumes the administrative tasks of the Chief of Staff. The vacancy of this sensitive position during the existing circumstance indicates a significant defect in the chain of command and orders. However, the interference of the regime’s allies in this position outlines the impact they have on the chain and the depth of their intervention. Their interferences may be breaking the centralization and bureaucracy of the regime’s military decision making, swaying decisions in their favor. The chief of staff is the central position of the “Army and Armed Forces,” and it supervises and commands all corps, divisions, and combat units, as well as a large number of departments and divisions.

Corps, Divisions, and Military Units

All military corps, divisions, and units within the chain of command and orders report to the Chief of the General Staff. The “interactive figure” shows how the five military corps and the divisions affiliated with them are distributed. Additionally, the military divisions, bodies, and departments report directly to the General Staff without subordination to any corps.

All corps, divisions, and departments - except for the 18th Division - are currently led by Alawite sect officers from four governorates (Latakia, Tartous, Homs, and Hama). The position of the corps commander is almost a formal administrative position, while the division commander has more power due to his direct command of the combat military unit, and this power varies according to the division’s number and the nature of its military tasks.

From another perspective, these units still maintain their party formation and are linked to the ruling Baath Party until now, including branches, divisions, and party cells. The military personnel are still generally prevented from affiliating politically with anything other than the Baath Party, despite the abolition of Article 8 of the Constitution.

On the other hand, both the Iranian and Russian military interventions influenced the military units and their leaders and officers. Russia had the most significant and powerful influence on a large number of units such as the Fifth Corps, the Republican Guard, the 17th Division, the 25th Division, the Air Force Command, and Air Defense.Furthermore, the Russian military advisors have penetrated all military units from divisions to battalions. Unlike Russia, Iran is satisfied with good relations with some commanders and officers of specific units due to some interests with the commanders of these units, such as Fourth Division, Fourth Corps, and Ninth Division) and some branches of the intelligence agencies.

Conclusion

After 2011, it is apparent that the Syrian army’s chain of command and orders has been greatly affected by several factors and variables. The most significant being the regime allies’ intervention in the military and its growing impact. The foreign interventions are primarily connected to Russia’s influence, more than Iran, as Russia is involved in the official circles of influence and informal networks. Sometimes Russia influences by bypassing outlined decision-makers in the chain of command, breaking the traditional centralized decision making mechanisms. This has illustrated the regime’s inability to control all military units effectively.

Despite the growing Iranian and Russian influence on the military and security institutions, Bashar al-Assad, as the “President of the Republic and Supreme Commander of the Army and Armed Forces,” still formally controls the chain of command and orders.However, this formal control does not imply complete control over appointments and the flow of orders. These may be influenced by regime’s allies according to their respective balance of interests and needs.

Bashar al-Assad has taken steps to reduce the influence of his allies on the military establishment, attempting to show a centralized chain of command. Before Russia’s intervention, this was the situation and was showcased through periodic military appointments that tried to mitigate the impact of interconnected networks. Chiefs of Intelligence agencies enjoy relative stability due to the unique nature of the work entrusted to them and the difficulty of assigning these positions to all officers. On the other hand, the promotions and appointments processes are still executed in a non-professional manner. The decisions are governed by loyalty, which above all, is linked to sectarian fanaticism that continues to penetrate the army from top to bottom.

Despite all its complexities and mixed dynamics, the military chain of command is a critical component of the Syrian regime. As the anchor point and head of the command, Bashar al-Assad assumes direct responsibility for the decisions made after 2011, including violations committed by the army and security services against civilians, documented massacres, and the use of internationally prohibited weapons including chemical weapons.

Dr. Ammar Kahf | Syrian opposition and Assad regime agree to Russian-brokered agreement for Daraa al-Balad

Dr. Ammar Kahf, Executive Director of Omran Center for Strategic Studies shared his analysis on TRT World regarding recent developments in Daraa al-Balad, the current talks brokered by the Russians, and the humanitarian conditions.

on the recent talks between the Syrian opposition and the Syrian regime in under the direct supervision of the Russian.

For more: https://bit.ly/3zWV6cQ

The situation in Daraa is dire. Here’s how it might play out.

In a symbolic blow to the anti-government uprising born in Daraa in 2011, the Bashar al-Assad regime and Iran-backed militias are once again attempting to violently subdue the Syrian provincial capital, which is considered the birthplace of the revolution that began a decade ago.

The most recent round of clashes was sparked by Syria’s May 31 illegitimate presidential elections. Several of Daraa province’s cities refused to participate in the elections and civilians took to the streets in protest.

On the day of the elections, the Syrian regime was forced to move the election center from the Baath Party Division building in Nawa city to the district center in the middle of the security square, where branches of the regime security agencies are located. This prompted the flight of most of the working members of the party’s division to the capital, Damascus, for fear of being targeted.

As a result, several neighborhoods in Daraa province were placed under a brutal siege. In late June, the Fourth Division of the Syrian army and other regime forces encircled the city and cut off all roads leading to Daraa al-Balad in the south, preventing the entry of food and medicine as well as the entry or exit of civilians. The regime and its allies proceeded to cut off electricity, water, and communications. One checkpoint remains open for residents, but it is under the control of the Military Security Branch and the Mustafa al-Kassem militia—a troubling scenario for civilians.

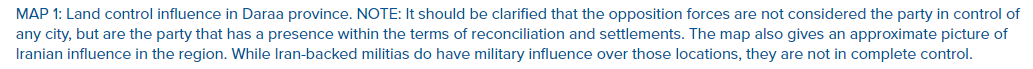

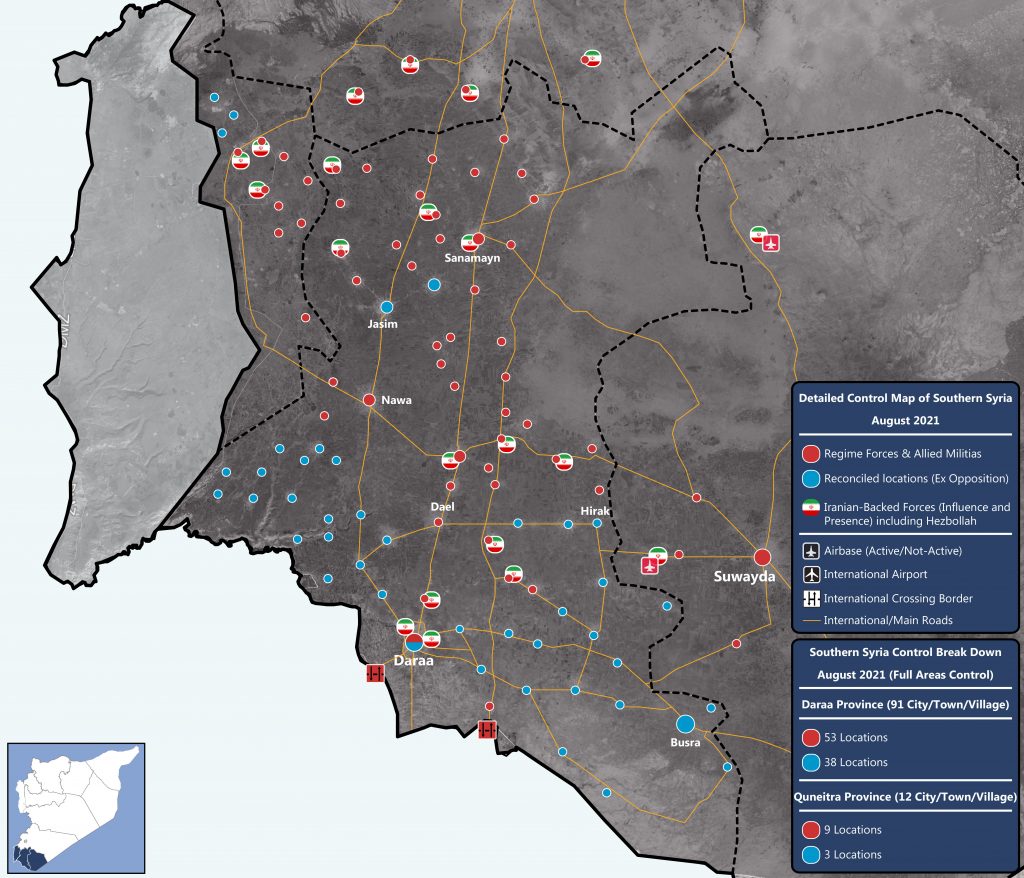

Daraa hasn’t witnessed a military campaign like this since the regime took control of the province in July 2018. Following that takeover, the region was divided into settlement areas, as happened in Daraa al-Balad, Busra al-Sham, Tafas, and other areas under regime control (MAP 1). Members of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) remained, forming sleeper cells, such as the Popular Resistance in the south—an armed group from Daraa province that was formed in November 2018—in several towns that refused the terms of a settlement with the regime, which exposed them to attacks. Other formations of the FSA joined the Fifth Corps—a volunteer-based force—under direct Russian control. The most prominent outgrowth was the Sunni Youth Forces, which now forms the forces of the Eighth Brigade in the Fifth Corps.

The complex reality of influence and control after the 2018 settlement

Despite the Assad regime’s control over Daraa since the 2018 settlement, the reality on the ground indicates that there are three spheres of influence in the province. The first is the area considered the center of negotiations between the opposition and regime, which is under direct Russian supervision. In this area, the regime maintained institutional control but was denied a security presence. The second sphere of influence comprises of settlements where the regime has all-out military control, such as Bosra al-Harir, al-Harak, Saida, and surrounding towns, as well as western areas like Jassem and Newa. Lastly, the third includes areas seized by the regime without signing a settlement agreement, such as Dael, Inkhil, and al-Hara.

Iran’s consolidation of influence in Daraa is one significant implication of this power diffusion. Via the Fourth Division, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and militias deployed in Daraa, Iran has successfully expanded its influence in the south and established a military presence in strategic locations near Syria’s southern border. Recent developments are further evidence of Russia’s failure to contain Iran in Daraa. While the Russians led the initial negotiations, Iran subsequently upended the process, empowering local allies to take military control of the province.

Daraa developments in light of the regime’s army being dispersed between Russia and Iran

Beginning on June 25, regime forces imposed a complete siege on the neighborhoods of Daraa al-Balad (inhabited by approximately fifty thousand people): the internally displaced camp, Palestinian refugee camp, al-Sad Road, and the farms in the areas of Shiah, al-Nakhla, al-Rahiya, and al-Khawani. The siege is meant to punish civilians for ongoing demonstrations since 2018 and the refusal of Dara al-Balad residents to participate in the voting process. As the dispute escalated, the Central Committee of Daraa al-Balad met with Russian General Assad Allah, who threatened to storm dissenting neighborhoods but agreed to prevent Iran-backed forces from taking military action in the city.

After several meetings between the Central Committee and regime, the two parties agreed to hand over the remaining light weapons of former FSA fighters who are not part of the Fifth Corps in exchange for lifting the siege imposed on Daraa al-Balad and an end to the regime’s military campaign there. The two sides also agreed to construct a new settlement to clarify missing or gray areas in the 2018 settlement.

However, the agreement has not been implemented so far due to several obstacles created by Major General Husam Louka, the head of General Security Directorate, Brigadier General Ghaith Dalah, commander of the Fourth Division, and Syrian Defense Minister Ali Ayoub—all of whom have stated that the regime’s goal is absolute control over the entire neighborhood of Daraa al-Balad. This proclamation upset the Russians, who know Iran is escalating the conflict and attempting to strengthen the control of its local allies near the Syrian and Jordanian borders.

It is possible to deduce several important points from the rapid developments in Daraa al-Balad during the past week:

- The non-interference of the Russians during the military operation via airstrikes gave ex-FSA fighters ease of movement. The Russians’ lack of intervention may also explain their unwillingness to complicate the situation of the opposition-held areas in the north, and not to assist the Iranian allies on the ground to advance in a way that would hurt the fragile agreement between Russia and Turkey there.

- The fall of many regime military points and checkpoints within hours to the hands of ex-FSA using only light weapons indicates the fragility of the regime army’s structure in these locations. This fragility is due to their dependence on untrained fighters and/or a collapse of the soldiers’ morale.

- The rapid response of other settlement locations—blocking roads and attacking regime security points—in the eastern and western countryside of Daraa contributed greatly to the dispersal of the regime’s focus on a specific geographic area.

- The media campaign that started at the beginning of the siege on Daraa al-Balad incited international responses. The United States and the European Union issued several official statements condemning the campaign and calling for an immediate ceasefire.

Amidst this military escalation on Daraa al-Balad and the eastern and western countryside and the continuation of negotiations between the Central Committee and the regime, Daraa faces several scenarios.

A new settlement and forced displacement

The way the Assad regime dealt with the cities of Tafas and al-Sanamayn could foreshadow what happens in Daraa al-Balad in the coming days. After the regime attack on the city of al- Sanamayn in March, Russia intervened through the Fifth Corps to resolve the conflict and imposed a truce that ended with the deportation of fighters to the north; those who stayed have had to hand over weapons. In January, the same scenario occurred in Tafas, after the regime demanded that the people hand over light and medium weapons and that those who wished to leave Daraa go north.

According to this scenario, Russia may intervene to end the attack on Daraa al-Balad, put an end to the military operation, and sign a new agreement. However, the details and terms depend on the size of the Assad regime’s losses in the coming days. This seems to be the most realistic scenario for the regime, considering its accelerated losses and negotiations with the Central Committee of Daraa.

The area under the shadow of the Fifth Corps

The FSA’s recent success will give it an upper hand at the negotiating table. The Central Committee may negotiate a stop to the escalation in all towns and cities in return for stopping the military campaign, lifting the siege, and deploying checkpoints for the Fifth Corps in Daraa. Although this scenario is possible, it requires the approval of Russia and Jordan and it is unlikely that Iran and the regime will accept this scenario, which would threaten their control in the south.

Return to the 2018 settlement

If the Russians do not intervene in the coming days to stop the regime’s military campaign and the FSA continues to maintain the military escalation line and preserve its gains on the ground, the regime may turn to pre-June 25 conditions to prevent further losses and the further bolstering of the opposition. The situation at the time gave the regime full administrative control over the area but with very limited security control.

Worst case scenario: absolute control by the regime without any reconciliations or settlement

This scenario is best for the Assad regime and its ally Iran, which does not favor Russia. It depends on launching a vast military campaign on the neighborhood and imposing absolute control without referring to any new settlements, which will result in a massive campaign of arrests for the residents and will not even allow them to flee to the north of Syria. This scenario is preferable for Iran because it will create a large vacuum in the region that can be exploited by local allies at the administrative, military, and security level, which will therefore pose a major challenge to Russia in regard to controlling the Iranian presence near the Syrian and Jordanian borders.

In the long run, this scenario will enhance the fragility of the security situation in the region for an array of reasons. This includes: an increase in assassinations against Iran’s allies in the region; the high incidence of clashes between members of the Eighth Brigade and Iran’s allies; and an increase in the number of Israeli attacks on Iran-backed forces. In sum, this scenario is considered the worst for Daraa and its people because it serves only Iran and its local allies from the regime.