Rateb

Monthly Briefing on The Events of The Syrian Scene - June 2024

General Summary

This report provides an overview of the key events in Syria during the month of June 2024, focusing on political, security, and economic developments. It examines the developments at different levels.

- Politically, the normalization steps between Turkey and the Assad regime are progressing. The announcement of local elections by the Autonomous Administration has angered Turkey, increasing its threats.

- Security, violence has escalated across Syria, with 429 civilian and 700 military casualties in the first half of the year.

- Economically, the significant rise in prices continues to be a major issue, alongside increased Iranian influence in the Syrian financial sector.

Turkish Normalization with the Assad Regime: Political Transformations and Future Outcomes

The most discussed topic regarding the Syrian issue is the latest developments in Turkish rapprochement with the Assad regime. Following the Iraqi Prime Minister's statement about creating a basis for dialogue between the regime and Turkey and confirming that talks are ongoing, Turkish statements about upcoming normalization steps followed. The Assad regime has waived its previous condition of Turkish forces' actual withdrawal from Syria to merely declaring their readiness to withdraw and making commitments, according to the regime's Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad. The Turkish Foreign Minister emphasized the importance of the ceasefire between the regime and the opposition, urging the regime to rationally use this period of calm to resolve its constitutional issues, achieve peace with its opponents, facilitate the return of millions of Syrian refugees, and unite efforts with the opposition to combat terrorism, particularly the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK). Russia is intensifying efforts to expedite the normalization steps between the two sides and facilitate a presidential-level meeting between Erdogan and Bashar al-Assad, capitalizing on Turkish concerns about local elections and the entrenchment of the AANES project. Turkey is pursuing a “parallel tracks” policy to improve its relations with Moscow while preparing for the pre-US election period and the potential implications of a Trump administration on the region.

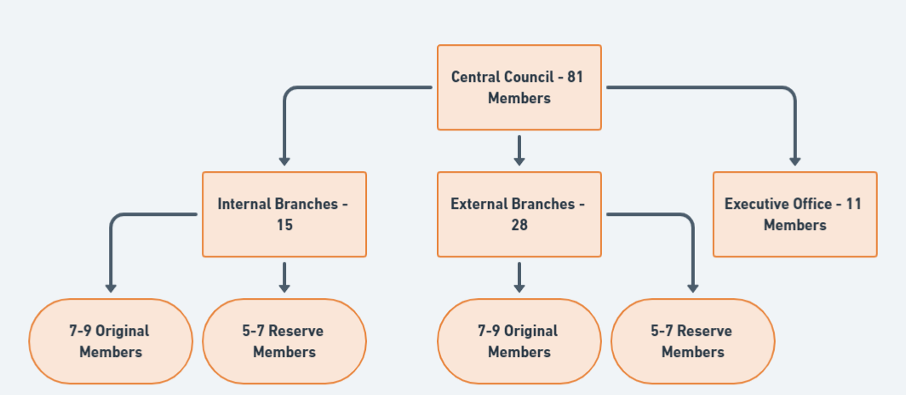

Despite the increased indications of Turkish rapprochement with the Assad regime this month, the normalization process began in late 2022 during quadrilateral talks at the security and intelligence levels under Russian auspices and Iranian participation. These talks went beyond being exceptional meetings to indicate the start of a new normalization path, though initially hindered by preconditions and external interventions. Turkey's insistence on bilateral meetings with the regime without other parties suggests it viewed the Iranian role as obstructive. As for the future of the normalization path, it still requires much time, as the proposed agenda from both sides seems complex and exceeds their capacities. Turkey aims to combat “terrorism” and dismantle the Autonomous Administration project in Northeast Syria, while the regime is unable to achieve this. The AANES 's High Election Commission announced the postponement of municipal elections, originally scheduled for June, to August in response to demands from political parties and alliances. The announcement of the elections faced Turkish rejection and threats to use force to prevent them, considering them a move towards division, as per Turkish statements. The US also declared that conditions are not conducive to conducting transparent and inclusive elections. This indicates that the postponement decision resulted from the lack of US support and serious Turkish threats, prompting local Autonomous Administration supporters to pressure for election cancellation to avoid new military operations. However, setting and then postponing the election date put the Administration in a dilemma, making it appear dependent on Turkish approval for any future entitlements in Northeast Syria. The Administration insists on postponing rather than canceling the elections, while recent Turkish moves toward normalization with the regime primarily target the Autonomous Administration project and open doors to various scenarios for the region's future.

Separately, the Negotiation Commission held its periodic meeting in Geneva, attended by several civil society representatives from within and outside Syria and Arab and European state representatives. The final statement emphasized that UN Security Council Resolution 2254 is the legitimate framework for reaching a sustainable political solution, asserting that Syria is currently unsafe for refugee returns, and rejecting “sham elections” in regime-controlled areas and those planned by the Autonomous Administration.

Increasing Indicators of Violence Escalation in Different Influence Areas

Despite Jordanian understandings with the regime and Arab pressures on the drug trafficking issue, Jordan still faces the threat of smuggling networks. Authorities foiled the largest smuggling attempt in months, seizing 9.5 million Captagon pills and 143 kilograms of hashish intended to be smuggled through Jordan to a third country.

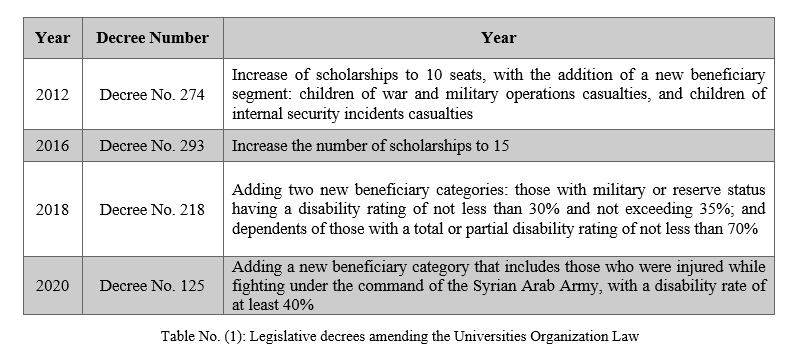

Regarding changes in the regime's military institution, following the cessation of extensive military operations and the regime's involvement in regional communication pathways, the regime seeks internal military structure changes. According to official statements, this aims to discharge reserve service members in three phases by the end of 2025, moving towards reliance on volunteers to build a professional army. Concurrently, the regime's Ministry of Defense issued an administrative order halting the recall of reserve officers aged 40 who have completed two years of service and discharging non-commissioned officers and reserve personnel who have completed six years of service.

In Suwayda, demonstrations against the regime continued, along with a campaign of posters against the People's Assembly elections scheduled for mid-July. The province also witnessed clashes between local armed groups and regime forces, sparked by the regime establishing a new security checkpoint following the abduction of 15 regime members by local groups in response to the regime's arrest of a civil activist.

In North Aleppo, the local council of Al-Bab city announced the opening of the Abu al-Zendin crossing between opposition and regime areas as an official commercial crossing to improve living conditions and enhance local economic activity. This decision coincided with increased indications of Turkish normalization with the regime and aligns with Russian understandings to open trade lines between influence areas. However, reactions varied, with traders and investors viewing it as a vital trade and movement artery and an opportunity to reduce smuggling operations and lower prices due to availability. Conversely, some residents and Syrian National Army members attacked the crossing, damaging some equipment in opposition to its opening, while several entities issued statements demanding civilian management of the crossing outside military faction control, overseen by local institutions responsible for managing the city and establishing mechanisms to secure the crossing economically and security-wise.

This month also saw a significant escalation in ongoing violence in Northeast Syria. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights documented the killing of 62 people, including 40 civilians, by various means, resulting from 37 acts of violence, including tribal conflicts, murders, about 20 operations by ISIS cells, and Turkish drone strikes. Indicators of violence have also increased across influence areas, with the Syrian Network for Human Rights documenting the killing of 429 civilians in Syria during the first half of 2024, including 65 children, 38 women, and 53 under torture. The highest proportions of victims were in Daraa 27%, Deir Ezzor 18%, and 14% each in Raqqa and Aleppo. The military death toll reached around 700 fighters in different control areas.

Continuous Price Increases Deepen the Economic Crisis

Amid the regime's economic decisions affecting living standards, the requirement for smart cardholders to open bank accounts to transfer support funds is significant. The Council of Ministers stated this step aligns with restructuring support towards targeted and gradual cash support. The regime is expected to abolish current subsidies on bread, fuel, electricity, water, and phone services, shifting the burden to the private sector due to its inability to meet living requirements, leading to significant price hikes and free market sales.

Under Presidential Decree No. 17 of 2024, Bashar al-Assad granted a one-time financial grant of 300,000 SYP (approximately $20) to retirees and government employees, including civil and military workers in the public sector. Given the Syrian pound's devaluation against foreign currencies, the grant is symbolic, covering only a few meals and failing to meet citizens' basic needs.

Clothing prices increased by 200% compared to last year due to rising cotton and yarn prices and the government's lack of intervention to control prices or support the clothing sector. Confectionery prices in Damascus markets also doubled compared to last Eid al-Adha. Despite the arrival of eight Iranian oil tankers loaded with crude oil and gas at Banias port in Tartus countryside, indicating continued Iranian support and sanctions breaches, the regime raised fuel prices amid a local fuel crisis. Due to rising fuel prices and shortages, increased temperatures, and the start of the harvest season, amperage companies in Damascus and its countryside raised kilowatt-hour prices in several areas.

The regime's shift towards export policies, away from self-sufficiency and market regulation, caused price increases. The regime's exports increased by 30% in the first half of this year compared to the same period in 2023. However, the number of Syrian fruit and vegetable trucks exported to Jordan dropped by 80% due to Jordanian restrictions amid anti-drug smuggling efforts.

Iran continues to expand its influence in the Syrian financial sector by opening institutions and banks. The Islamic City Bank, jointly owned by Iran and Syria with a capital of 50 billion SYP, recently opened, making it the fifth Islamic bank in Syria. Meanwhile, Russian tourism investors supervised the construction of two tourism facilities in Latakia province, with 50% completion. The number of Russian visitors to Syria reached 780,000 by the end of May, a 10% increase from the same period last year.

In Northeast Syria, the AANES published the 2024 budget details, with total revenues of $670 million and expenditures of $1.059 billion, indicating a projected $389 million deficit. Turkish airstrikes on SDF economic hubs, including energy infrastructure, caused estimated losses exceeding $500 million, contributing to economic paralysis. Given the estimated $1 billion expenditures, the region continues to face living crises at all levels, including rising prices, material shortages, and poor public services. Meanwhile, the SDF began delivering the first batch of wheat procured from Northeast Syria farmers to regime grain collection centers in southern Qamishli, transporting over 2,500 tons of wheat in 24 hours.

In North Aleppo, the Syrian-Turkish Energy Company raised household and industrial electricity prices to 3.6 and 4.1 Turkish liras per kilowatt, respectively, citing changes in Turkish electricity prices. The Syrian Interim Government set wheat prices in its areas at $220 per ton, $110 less than last season and the lowest price among influence areas: $310 per ton in Idlib and Northeast Syria and $360 in regime areas. This price is disproportionate to farmers' production costs. In Idlib, the “Salvation Government” reiterated financial transfer delivery regulations in the sent currency to organize the financial market, increase trust, and enhance control over financial policies and price regulation, reducing the need for black market currency conversions.

The Impact of Reduced Humanitarian Aid on Syria

Introduction

Due to the escalating crises and conflicts worldwide, the growing number of individuals requiring relief and humanitarian assistance, and the significant disparity between needs and resources(1),Syrians face complex challenges and responsibilities amidst political deadlocks. This situation necessitates an awareness of the implications for the level of services provided and the number of beneficiaries within Syria, considering the deteriorating social and economic conditions for Syrians in host countries.(2)

According to the Global Humanitarian Overview report issued by OCHA for 2024, approximately 308 million people worldwide require humanitarian assistance, necessitating $48.64 billion to aid 187.8 million people in 70 countries through 36 coordinated response plans. Only 15.3% of the plan has been funded so far, with $7.42 billion in funding, which is 35% less than the $11.40 billion recorded during the same period last year. Additionally, the total reported funding amounted to $4.34 billion, which is 42% less than in 2023 ($7.44 billion). Reported funding from major donors in the first four months of 2024 has also decreased compared to 2023.

Local and Regional Implications

This reduction will have several implications for Syria on the local level, such as worsening living conditions, increased migration waves, heightened militia activity, the growth of the war economy, and involvement in illicit activities such as drug and arms trafficking. Additionally, societal violence, including theft, kidnapping, and extortion, will negatively impact local security and stability indicators.

On the regional level, economic pressures on host countries will increase, leading to a higher likelihood of these countries pushing Syrian refugees to return voluntarily or forcefully and taking measures to tighten restrictions on them. Additionally, the risk of drug trafficking in neighboring countries (Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, Iraq) may increase, using their territories as transit points to the Gulf and Europe.

Syrian actors in the relief and development field will face several direct challenges, including:

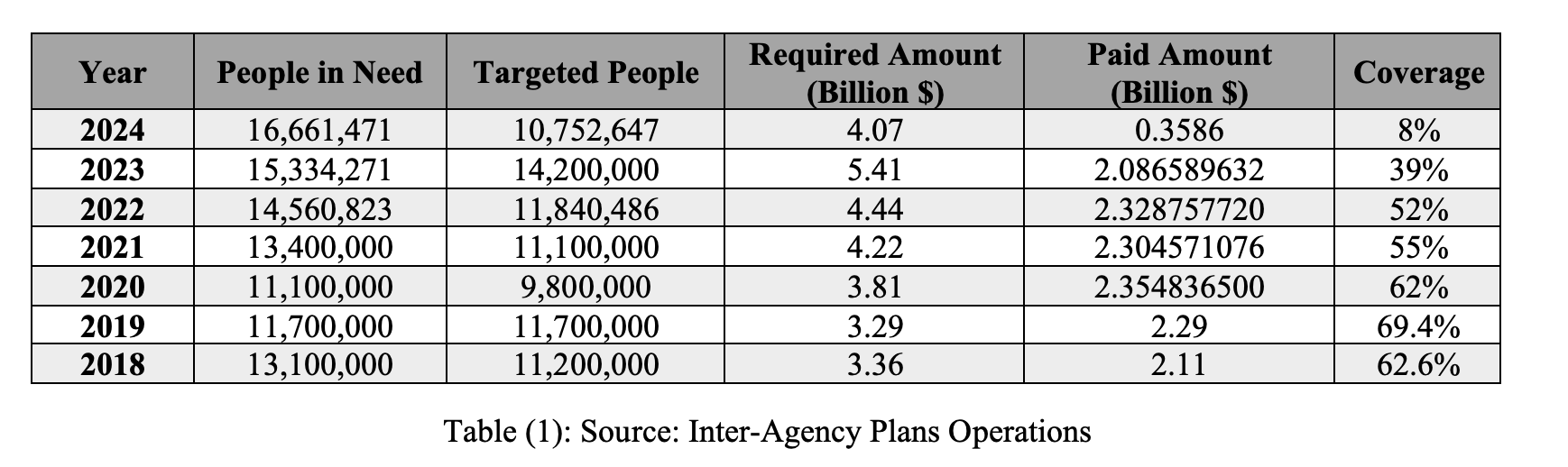

- Severe Food Security Crisis: The reduction in humanitarian funding since 2023 to $2.1 billion (39% of needs) led the World Food Program (WFP) in mid-2023 to reduce the number of people receiving aid from 5.5 million to 3.2 million (a 40% reduction) starting in July 2023. The program announced the cessation of its general food aid across Syria in January 2024 due to severe funding shortages, marking the seventh and largest reduction since the program began its work in Syria.

- Increased Needs: According to United Nations estimates, around 16.7 million people need humanitarian assistance, up from 15.3 million in 2023, the highest number since 2011. Among them, 7.2 million people are internally displaced in scattered areas, including 2.05 million in overcrowded camps.

- Severe Funding Shortages: Only 8% of the required funds have been received, with $358 million collected out of the $4.07 billion needed by May 2024 to meet the immediate humanitarian needs of 10.8 million targeted individuals. Many local organizations in northwestern Syria have had to halt numerous service programs, lay off dozens of employees, and close offices in various towns and cities in the countryside of Aleppo and Idlib.

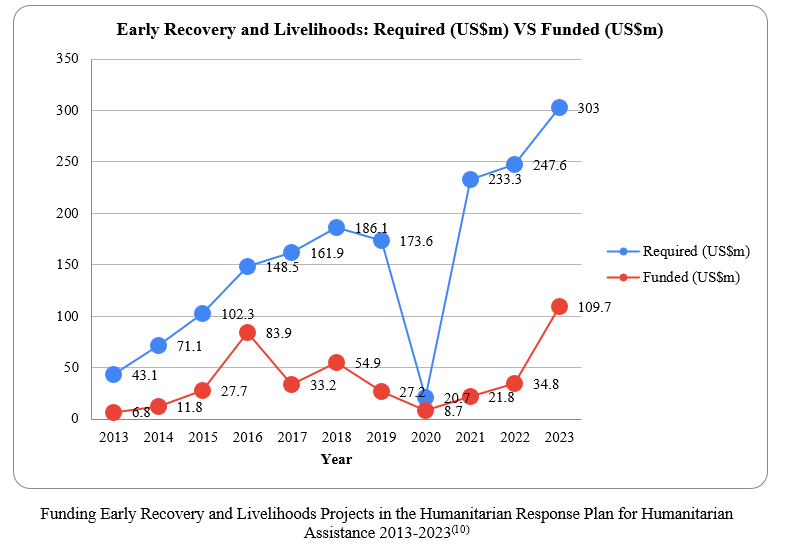

The following table shows the gradual increase in people in need of humanitarian assistance between 2018 and 2024, in contrast to the decrease in the percentage of funding received compared to the required funding, from 62% in 2018 to 39% last year and 8% this year:

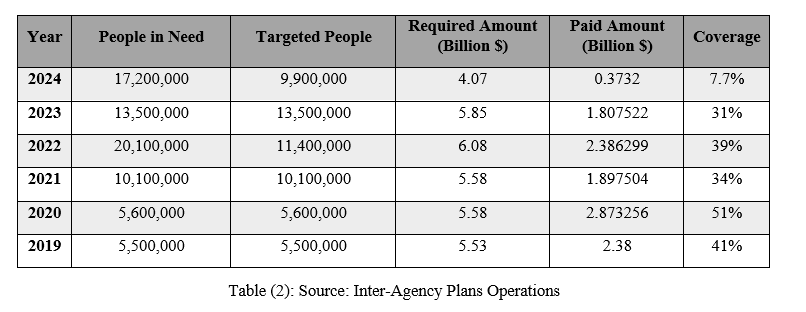

Increased Pressure on Services in Host Countries: It is expected that more than 19 million people will need assistance in 2024, including about 6.4 million refugees and 12.9 million affected members of the host community. Due to reduced funding and the need to prioritize strategically, the collective funding request for 2024 has been reduced to $4.1 billion compared to $5.8 billion in 2023 after reviewing requirements based on priority needs. As a result of the increasing funding crisis, the number of Syrian refugee families in Lebanon receiving cash assistance has been reduced to about one-third in 2024. The World Food Program in Jordan announced a reduction in its monthly food aid to 465,000 refugees in mid-July 2023 and excluded about 50,000 others from monthly assistance due to funding shortages.

The following table shows the increase in people in need of humanitarian assistance in the five host countries (Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, Iraq, and Turkey) against the decrease in coverage between the required amount and the paid amount.

Deterioration of Services (Water, Sanitation, Care, Electricity, Education): The deteriorating services for displaced individuals in collective centers will increase the risk of resorting to negative coping strategies. About 2.3 million women of reproductive age, including 500,000 pregnant and lactating women, will lose access to essential reproductive and maternal healthcare. Additionally, 2.5 million out-of-school children will miss the opportunity to return to school, threatening the future of an entire generation and depriving children of their basic right to education(3).

Strategic Recommendations

Despite donor pledges during the eighth Brussels Conference for "Supporting the Future of Syria and the Region" amounting to €7.5 billion ($8.1 billion), with $3.8 billion allocated for 2024 and $1.3 billion for 2025, the importance of addressing the potential for funding cuts and reduced aid remains significant. Syrian actors in the political, humanitarian, and developmental sectors must urgently address this challenge through several policies:

- Operational Alliances: These alliances ensure organizational independence while enhancing cooperation and coordination for effective project execution, preventing activity and project duplication.

- Syrian-Designed Comprehensive Response and Recovery Plan: Syrian actors should develop a comprehensive plan as a reference for response and recovery priorities, updated annually.

- Multi-Dimensional Advocacy Policies: Alongside traditional advocacy, innovative advocacy through coalitions can enhance benefits and broaden advocacy efforts both geographically and sectorally.

- Economic Empowerment Policies: Develop statistical and information collection tools, support small and medium-sized projects, and provide vocational training to create job opportunities, thereby reducing dependence on external aid. Implement basic infrastructure projects (water, sanitation, electricity, health, education) to enhance economic recovery and improve living conditions.

Conclusion

International involvement is crucial in Syria's response and recovery efforts. However, the capabilities, networks, and experience of Syrian actors can drive the development of an executive vision for the region's requirements, transitioning them from implementers to planners and implementers simultaneously.

([1]) The disparity between needs and requirements reached an unprecedented level of $31 billion by the end of 2023, with a total paid amount of $24.28 billion, or 43% of the required amount estimated at approximately $56 billion.

([2]) The year 2023 ended laden with significant difficulties and challenges faced by the world, starting with the earthquake that struck Syria and Turkey in February, followed by the conflict in Sudan in April, which left 30 million people in need. Additionally, the Israeli aggression on Gaza resulted in the deadliest humanitarian crisis in the sector since the Rwandan genocide in 1994. Alongside all these crises, conflicts continued in Syria, Ukraine, Afghanistan, Yemen, Congo, Haiti, and other regions.

([3]) Resident Coordinator and Humanitarian Coordinator Mr. Adam Abdelmoula Press Briefing on the humanitarian situation in Syria, 22-03-2024. Link: https://2u.pw/EGrZ56mr

Protests in Al-Suwayda in Syria: Security Challenges and Persistent Demonstrations

Executive Summary

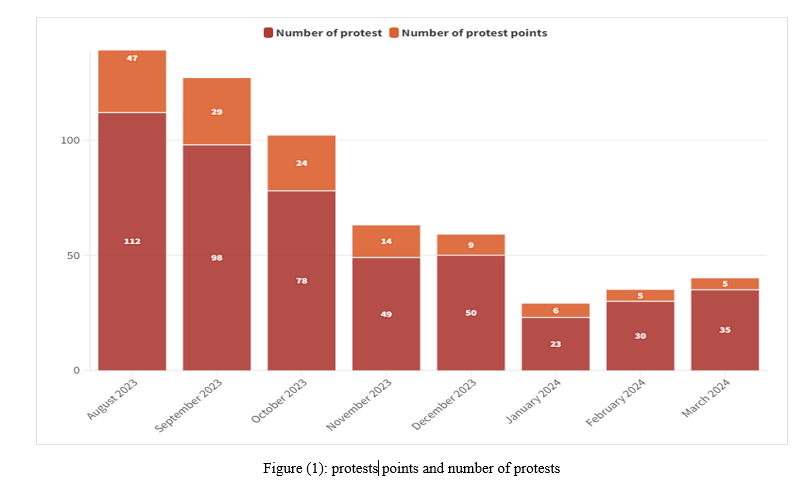

- The uprising in Al-Suwayda Governorate reached its eighth month by April 2024, advocating for economic improvements and political transition in Syria through the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 2254. The protests called for the overthrow of the regime and the removal of its security hold over the city, including demands to shut down Ba'ath Party headquarters. The extent of the protests has fluctuated, expanding, and contracting in response to shifts in the dynamics of the movement in Al-Suwayda and the varying positions of spiritual and religious authorities after the first month. The three religious’ leaders, Hikmat Al-Hijri, Hamoud Al-Hannawi, and Yousef Al-Jarbou, unanimously agreed on the necessity of economic reforms. However, Sheikh Yousef Al-Jarbou's stance more closely aligned with the Assad regime's narrative in the governorate. He also led the Druze religious authority during regime events, coinciding with his regular meetings with leaders of several militias opposing the movement in the governorate.

- The protests peaked in August 2023 but gradually subsided, eventually concentrating in Karama Square in Al-Suwayda and the towns of Al-Qrayya and Salkhad. The decline can be attributed to the shift of people from the rural areas of the city towards the main squares to intensify the gatherings. Additionally, militias active in the eastern and western rural areas of the governorate resumed their involvement in drug trafficking to the Jordanian borders. These militias have threatened the movement several times, fearing that the protests might threaten their trade or that they might later be targeted by the protesters themselves.

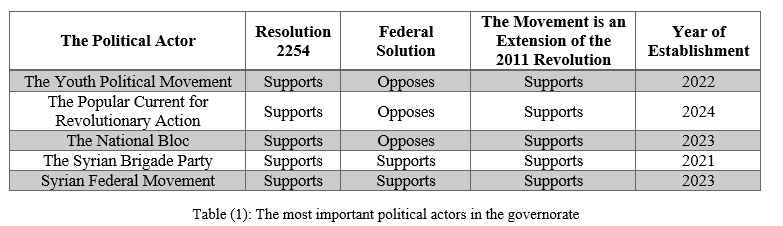

- The disagreement among the political factions in the governorate manifested in the proposed administrative structure of Al-Suwayda. All political factions in the governorate agreed on the necessity of economic reforms. However, the suggestion by the Syrian Brigade Party and Syrian Federal Movement to federalize Al-Suwayda was a point of contention for the other factions, who viewed it as an attempt to impose a political vision on the movement that would lead to a partial political solution not encompassing other Syrian provinces.

- The anticipated scenarios for the movement fall within three main axes: The first is the proposal by the Syrian Brigade Party to implement federalization in Al-Suwayda as an administrative solution for the governorate. This solution is seen as a threat to the movement because it is associated with the experience of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Northeast Syria, which opened a confrontation front with the Turkish government, as it threatens Turkish national security. Additionally, the movement is regarded as another separatist attempt in southern Syria, giving the Assad regime a pretext to use violence in the governorate. The second scenario involves the movement's ability to create shared spaces either with other regions, aiming to align local demands with national demands that extend beyond the geography of the provinces outside regime control, or even to initiate dialogue with neighboring countries concerning their security concerns, such as the production and smuggling of Captagon, particularly concerning Jordan. The third scenario sees the regime continuing to operate on a no solution basis while the effectiveness of Captagon smuggling routes in the governorate continues. This, combined with the lack of expansion of the movement, might prompt militias involved in the trade to destabilize the city's security if the movement becomes a threat to their smuggling operations.

Introduction

The uprising in Al-Suwayda Governorate continued into its eighth month by April 2024, demanding economic improvements and political transition in Syria through the implementation of Resolution 2254. The protests have called for the overthrow of the regime and an end to its security grip on the city, including demands to close the Ba'ath Party headquarters. This paper aims to examine the events in Al-Suwayda from July 2023 to March 2024, analyze the map of actors influencing the movement, understand its extension and response to security changes in the region, evaluate the role of religious authorities, and explore future directions for the field scenario in Al-Suwayda.

Changing Intensity of Protests and Multiple Factors

Since the beginning of the uprising, the extent of the protests in Al-Suwayda has varied, influenced by changing security and field events that the movement has undergone. Additionally, the varying stances of the spiritual authorities after the first month have influenced some of the movement's demands. These authorities have unanimously agreed on the necessity of economic reforms in the governorate, while their positions on the political demands related to political reform and the implementation of Resolution 2254 have differed.

Sheikh Youssef Al-Jarbou's position has closely aligned with the regime's narrative in the governorate(1). He criticized the political demands of the demonstrators as incorrect and led the Druze religious authority during the regime’s events and activities from August 2023 to February 2024. On October 12, 2023, he participated in the morning of the martyrs of the Military College in Homs.(2) Sheikh Youssef also held frequent meetings with Safwan Abu Saad, the governor of the Damascus countryside, who is originally from Suwayda, and dealt with local militias that posed a threat to the movement and protesters in the city. His dealings with the leaders of the Saif al-Haq militia, Radwan and Muhannad Mazhar, who were heavily involved in drug trafficking and security unrest, were of particular importance(3).

While Sheikhs Hamoud Al-Hannawi and Hikmat Al-Hijri's positions were closer to the popular movement, they varied in their opposition to the regime's authority in the governorate. Sheikh Hamoud Al-Hannawi participated in several protests and supported the public demands, urging people to demand their rights in a clear and bold voice. Meanwhile, Sheikh Hikmat Al-Hijri remained committed to his narrative that the political and economic demands of the protesters must be met, alongside his calls for local factions to protect the movement, thereby preserving civil peace and preventing the protests from turning into violent conflicts between the protesters and the regime forces in Al-Suwayda. The divergence in the positions of religious authorities, on the one hand, and the Assad regime's choice of a no-solution strategy, relying on time to diminish the movement after the protests failed to expand beyond Al-Suwayda to Daraa or other regime-controlled cities, on the other hand, led to a shift in the momentum of the protests in terms of number and spread across the villages of the governorate.

Figure (1) shows that the protests peaked in August 2023, after which the protest sites gradually receded to concentrate mainly in Karama Square in Al-Suwayda and the towns of Al-Qrayya and Salkhad. The decline is attributed to people moving from the rural areas of the city towards the main squares to intensify gatherings, especially on Fridays. Additionally, militias active in the eastern and western rural areas of the governorate returned to their activities in drug trafficking and its transfer to the Jordanian borders. These militias have threatened the movement several times, fearing that the protests might jeopardize their trade or that they might later be targeted by the demonstrators themselves.

Efforts to Organize the Movement and the Interwoven Demands

Some community elements in Al-Suwayda began organizing themselves into political entities with the onset of the Syrian revolution in 2011, but most remained inactive due to the specific conditions imposed by the city on Assad's regime behavior towards it. The regime avoided direct confrontation with local factions or religious authorities to ensure that a southern opposition pocket comprising Al-Suwayda, Daraa, and Al-Qunaitra did not form against it. Additionally, these entities did not join the traditional opposition represented initially by the Syrian National Council and later by the Syrian Coalition. However, as the movement in Al-Suwayda crystallized over several waves, the longest of which began in August 2023, some political components in the governorate became more active, and their demands became clearer, organized around three axes: the administrative structure of the governorate and its relationship with the central authority in Damascus, the nature of the required political reforms, and the extent to which the demands align with those of the 2011 revolution and international resolutions, especially Resolution 2254, which mandates a political transition in Syria.

Table (1) illustrates the key political actors in the governorate and their positions on the previously mentioned axes. It shows a consensus among political entities on the necessity of political transition, affirming that the popular movement in the governorate is part of the broader narrative of the 2011 popular movement with similar political and economic demands. However, the political disagreement among these components lies in their divergent views on Al-Suwayda's role within Syria's governance structure. The Syrian Brigade Party, established in 2021, believes that federalization is the most effective solution for political reform in Syria. This view is supported by several local political currents in the governorate, along with the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) based in Northeast Syria, which welcomes the proposal. This proposal aligns with their broader vision of implementing a federal solution in Syria and exporting it to other regions like Al-Suwayda, thus potentially strengthening the SDC narrative if it can export its model to other areas with unique ethnic or racial characteristics. (4)

The popular movement has sustained its demands for political change and necessary economic reforms, alongside efforts to disassociate the Ba'ath Party from the state apparatus in the governorate. Protesters have moved towards permanently closing the party's headquarters or even converting some into public service facilities. This is juxtaposed with a strong emphasis on the need to protect state service institutions, which should remain neutral and not become entangled or influenced by the ongoing protests.

Protesters have closed several Ba'ath Party headquarters in Al-Suwayda city and its countryside, totaling 27 headquarters by the beginning of March 2024. Ten of these were transformed into service centers for the citizens of the governorate(5)In response, the Assad regime maintained its narrative that the presence of the party's headquarters is linked to the presence of service institutions in the city, which led it to reduce the operational capacity of its service institutions as a reaction to the closure of the party's headquarters. As the popular movement continued, demonstrators gathered in front of some service institutions and closed some of them in protest against their nominal and ineffective role in the governorate(6).

Regarding the stance of political actors in the movement, they attempted to protect state institutions, emphasizing their neutrality, and ensuring they were not targeted. However, some political currents sought to create alternative service and security bodies in the city. The Syrian Brigade Party initially established a Counter-Terrorism Force led by Samer Al-Hakim, but this initiative was met with a security campaign by the regime's Military Security, which resulted in the disbanding of the force and the killing of Al-Hakim in June 2023. Subsequently, the party announced the establishment of several service offices such as a water authority, a rapid medical intervention office, and civil defense. These establishments were part of the Brigade's efforts to introduce the concept of self-administration to the movement, capitalizing on the service vacuum left by the regime's absence in the city. However, the idea of these institutions did not gain popularity among other political currents due to their rejection of a partial political solution limited to Al-Suwayda rather than extending to other Syrian provinces.

Local Scenarios within a Turbulent Regional Environment

Since its inception, the Al-Suwayda movement has been closely tied to rapidly changing regional dynamics, manifesting in three main areas: first, the trade and production of Captagon; second, the normalization process with the Assad regime; and third, the presence of Iranian forces in Syria and the increasing frequency of Israeli attacks on these forces. Future regional changes could also influence the expansion or contraction of the movement based on the positions of neighboring countries regarding the proposed scenarios. On the local level, the potential scenarios include three possibilities: the risks associated with proposing self-governance, the movement's ability to open new spaces for cooperation both internally and externally, and the potential for the movement to be dominated and redirected.

· The First Scenario involves the Syrian Brigade Party's proposal for federalism in the city, which poses a risk to the movement by associating it with the SDF experience in Northeast Syria, which has opened a confrontation front with the Turkish government. This proposal also raises fears that the movement could be viewed as another separatist attempt in Syria, similar to the SDF's demands for an independent area, thereby strengthening its international stance in advocating for turning Syria into federations. This scenario would provide the Assad regime with a pretext to use violence in the province to assert control over Al-Suwayda under the guise of protecting Syrian territorial integrity. Previously, the Assad regime had no clear justification for using violence against the movement due to the unique demographic composition of the city and its reliance on two elements for the movement's decline. The first is linked to local groups causing security disturbances, and the second bets on time for the movement's recession and cessation if the demonstrators fail to form political forces or establish a national coordinating framework among all regions outside Assad's control.

· The Second Scenario entails the movement's ability to create shared spaces with other areas, aiming to align local demands with national demands that transcend the geography of the provinces outside regime control. This could involve transforming economic and political demands into a unified discourse, potentially revitalizing the political process, or even initiating dialogue with neighboring countries to address their concerns. An example of this is reassuring Jordan, which considers the smuggling of Captagon from Syrian territories as one of the most significant threats to its national security and is seeking solutions to halt its flow across its borders.

· The Third Scenario is based on the regime's reliance on a no-solution approach, while the effectiveness of Captagon smuggling routes continues in the province. With the Al-Suwayda movement not expanding beyond the governorate, local militias linked to the regime and Iran might destabilize the city's security if the movement threatens their smuggling operations. These militias are integral parts of the Captagon supply, production, and smuggling chains.

In conclusion, it is not possible to definitively predict one scenario over others without considering international variables, such as the war on Gaza and the ongoing Israeli raids on Iranian positions in Syria, as well as the perspectives of local political currents on the future of the movement and the city. The proposal for federalization within the movement would face Turkish opposition to prevent the Al-Suwayda movement from becoming a lever that the SDF might later exploit. Additionally, the way Jordan handles the Captagon issue and its potential coordination with local factions like the Men of Dignity Movement (Rijal Al-Karama) could protect the movement and open up other cooperative prospects with Jordan, potentially having economic or political dimensions in later stages. The challenge for the movement's coordinators and local factions remains in their ability to present a political front that reflects their demands and is consistent with the broader Syrian context, particularly as regional countries shift their focus in Syria to security motivations after previously supporting the movement and its political demands.

([1]) Contrary to Druze references: Sheikh Yousef Jarbou confirms his alignment with the Syrian regime, Al-Quds Al-Arabi, 30/08/2023, https://bit.ly/3J4naBg

([2]) Yousef Jarbou in Homs to condole the regime for the casualties of the "Military College," Al-Souria Net, 12/10/2023, https://bit.ly/4cHbGRR

([3])Suwayda: Groups linked to Military Security threaten to suppress the movement, Al-Madina, 09/11/2024, https://bit.ly/3vWaM3q

([4]) SDC supports the demands of Al-Suwayda protesters for self-administration and holds the Syrian government responsible for the deteriorating conditions, Al-Yawm TV, 21/08/2023, https://bit.ly/4aKKa4C

([5]) The pages of political currents, Al-Suwayda 24 page, and several local news networks were monitored, and data was cross-referenced among them during the period from August 2023 to March 2024.

([6])Protesters shut down several government departments and institutions, including the Directorate of Telecommunications and the Directorate of Agriculture, in protest against "the lack of response from government bodies to the demands of the citizens in Suwayda," Al-Suwayda 24 Facebook page, 05/11/2023, https://bit.ly/4aGTqpV

Monthly Briefing on The Events of The Syrian Scene

General Summary

This report provides an overview of the key events in Syria during the month of May 2024, focusing on political, security, and economic developments. It examines the developments at different levels.

- Politically, the trajectory of Arab normalization with the Assad regime remains volatile. The Arab League summit's statement and the suspension of the Arab Contact Committee reveal a more cautious Arab stance towards opening up to the Assad regime. Meanwhile, diplomatic normalization appears more stable, evidenced by Saudi Arabia appointing an ambassador to Damascus.

- Security, instability persists across Syria due to the Iranian-Israeli proxy war on Syrian soil and the presence of various militias in regime-controlled areas, along with local actor conflicts and their unstable models.

- Economically, all regions in Syria are suffering from an economic crisis exacerbated by the decisions of controlling authorities, with attempts to boost investment in northern Syria.

The Path of Arab Normalization with the Assad Regime: Challenges and Limited Progress

The path of Arab normalization with the Assad regime faces significant difficulties and challenges that the intervening parties struggle to address. Notably, the Arab Liaison Committee's meeting, intended to communicate with the regime, was canceled after Damascus failed to respond to inquiries regarding Captagon smuggling and other issues. Additionally, a meeting between the regime's foreign minister and his Jordanian counterpart, Ayman Safadi, yielded no progress on the Arab Committee's requests.

Despite Bashar al-Assad's attendance at the regular Arab summit held in Bahrain, without a scheduled speech, the final statement emphasized the necessity of resolving the Syrian crisis in accordance with Resolution 2254. This includes the transition process, ensuring Syria's security, sovereignty, and territorial integrity, fulfilling the aspirations of its people, eradicating terrorism, and providing a dignified and safe environment for the voluntary return of refugees. Reflecting the limited Arab openness, the Assad regime ceded hosting the next summit to Iraq. These developments indicate a more cautious and deliberate Arab approach to normalization with the Assad regime, reassessing the implications of opening up further in light of growing concerns that additional incentives to Assad could yield counterproductive results.

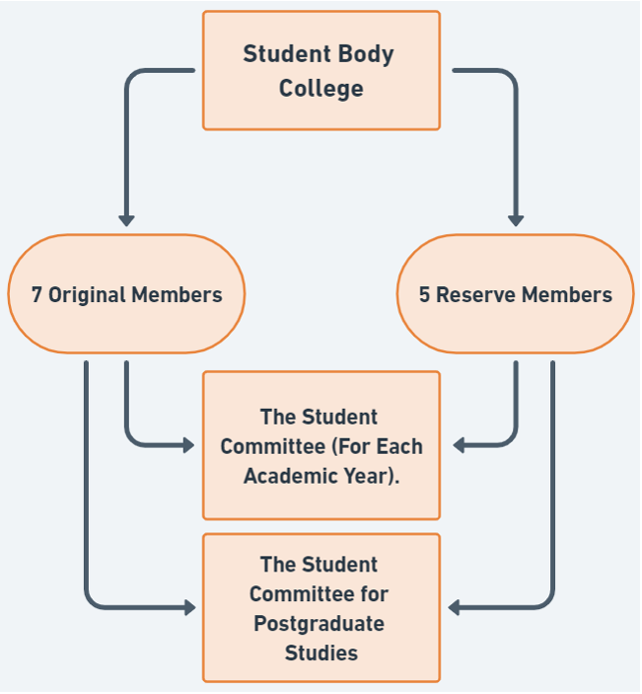

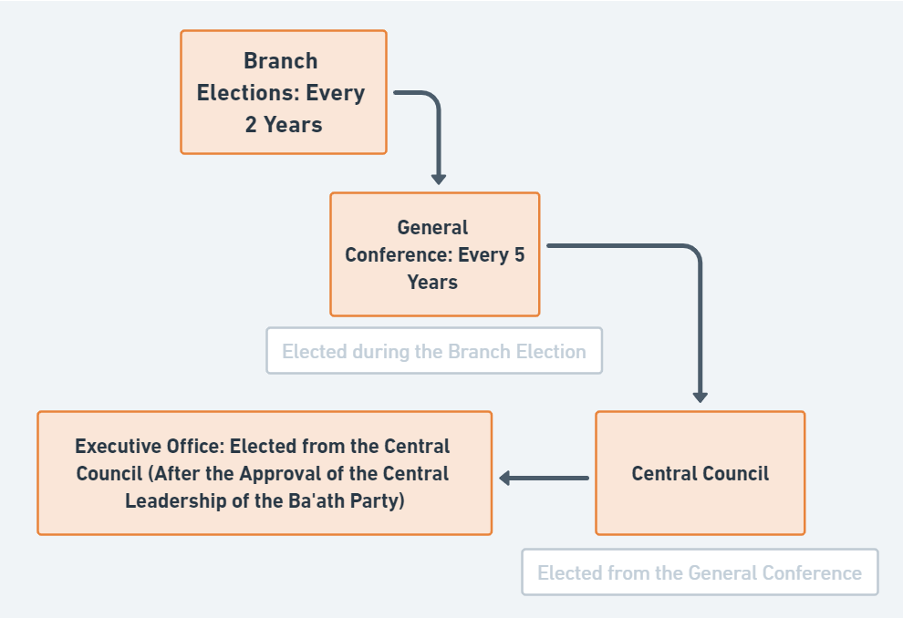

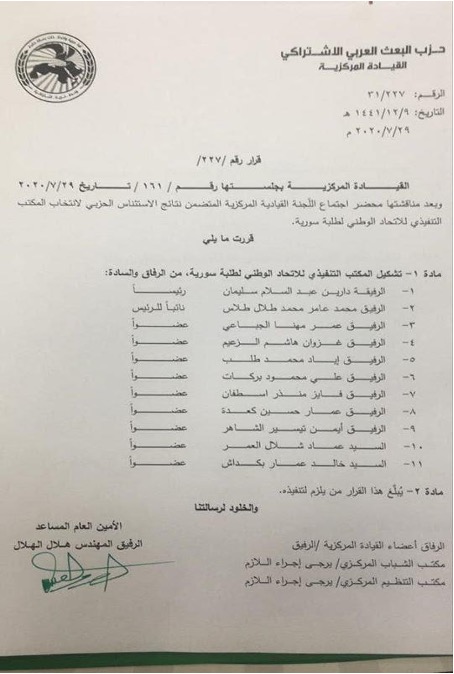

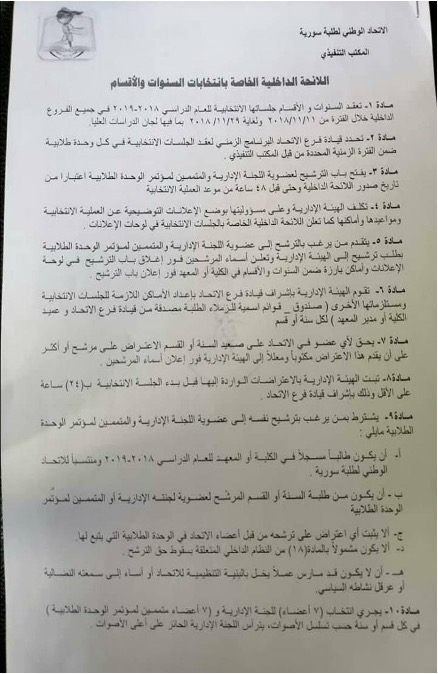

Locally, within the context of formal structural changes initiated by the regime, Bashar al-Assad participated in the expanded meeting of the Central Committee of the Arab Socialist Baath Party. The meeting resulted in Assad's re-election as Secretary-General of the party and the election of 14 new members to the central leadership. Additionally, members of the party's Central Committee at the provincial level and the new Control and Inspection Committee were elected. However, these changes are merely organizational adjustments within the party's structure, aimed at recycling the regime's allies to maintain the Baath Party's control over Syria's political and social landscape. These steps do not seem to contribute to genuine reforms that could satisfy Syrian parties and lead to a comprehensive political solution.

In northeastern Syria, the Autonomous Administration is making efforts to fortify the home front ahead of the municipal elections scheduled for the first half of July. Mazloum Abdi, the commander-in-chief of the SDF, held a series of meetings with Arab tribal sheikhs and notables in Deir Ezzor, where he acknowledged mistakes made by his forces during the pursuit of ISIS elements and pledged to release detainees and compensate those affected. This coincides with the issuance of the Autonomous Administration law on administrative divisions in preparation for local elections. The announcement of these elections has sparked significant controversy locally, regionally, and internationally. The US State Department stated that the conditions for free and fair elections in northeastern Syria are not met, while Turkey considers these elections a threat to its territorial integrity and national security. Under the new Administrative Divisions Law, northeastern Syria is now considered a single region divided into seven main districts. These laws and procedures are part of the administration's attempts to gain legal legitimacy over the region and establish a new status quo for future negotiations with other conflict parties in Syria. Additionally, these steps send messages to achieve political and field gains, raising concerns about the social, political, and legal consequences for Syrians residing in areas under the administration's control and the future of Syria in general.

Escalating Security Challenges in Syria

The security dilemma in Syria continues to worsen, with the country serving as a battleground for the Iranian-Israeli conflict. Israeli aircraft have targeted sites of Iranian militias in southern Damascus, Daraa, and Qusayr in Homs province, as well as a building managed by the regime's security forces on the outskirts of Damascus. These raids resulted in the deaths of 11 militiamen, including Syrians and Lebanese. In contrast, the "Islamic Resistance in Iraq" of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards carried out seven attacks targeting Israeli military sites in the occupied Syrian Golan. Additionally, an explosive device detonated in Damascus' Mezzeh neighborhood, killing one-person, injuring others, and burning cars. This marks the second such explosion in the same area within two months. In southern Syria, assassinations and clashes persist. Two regime forces members were killed by explosive devices planted in their cars north of Daraa. The regime has launched repeated security campaigns in the province, ostensibly to pursue wanted individuals involved in targeted attacks. However, mutual targeting and assassinations continue, affecting regime forces and former opposition fighters. These security policies have failed to establish stability in southern Syria. Meanwhile, weekly demonstrations in as-Suwayda persist despite the regime's attempts to intimidate protesters by sending large military reinforcements.

In Idlib, popular protests against Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) have escalated. HTS's attempts to peacefully contain these protests by promising reforms have failed. This month, HTS forcibly dispersed a sit-in in central Idlib, with security elements assaulting protesters with hands and batons. Abu Muhammad al-Julani, HTS's commander-in-chief, justified this action by stating that HTS had warned against any disruption to public interests and rules, considering most of the protesters' demands as already met. HTS's failure to end the protests peacefully has led to the use of force in an attempt to intimidate protesters, though they seek to avoid excessive violence to prevent expanding the protest area and gaining new supporters who have remained neutral.

In northeast Syria, Turkish artillery targeted several villages near the town of Tal Tamr in al-Hasaka countryside, and the shelling extended to villages in the countryside of Manbij city. In Deir Ezzor, the SDF conducted a security screening campaign in various areas and bombed several towns and villages west of the Euphrates River under the control of regime forces and Iranian militias, resulting in civilian injuries. Additionally, the SDF launched a security operation in the city of al-Busaira, east of Deir Ezzor, which led to the death of an Iraqi ISIS leader. The number of ISIS operations in the area has declined, coinciding with increased security measures and reinforced military checkpoints.

Attacks by tribal fighters on SDF headquarters and checkpoints in Deir Ezzor also decreased significantly during the second half of May 2024. This decrease followed heavy shelling by the SDF on villages and towns near the city of Mayadeen, believed to be a haven and staging point for tribal fighters. The SDF's strategy in dealing with tribal fighters appears to have two main approaches. Locally, the SDF is attempting to re-engage with Arab tribes by increasing the frequency of meetings between SDF leaders and tribal notables, providing incentives to tribal leaders, and promising to improve services in the region. From a security perspective, the SDF is pressuring pro-regime forces and tribal fighters by bombing their gathering places and launching operations south and west of the Euphrates to incite local populations against them and increase the regime's burden in containing these fighters.

Economic Empowerment Initiatives and Challenges in Northern Syria

To highlight new patterns of humanitarian intervention and opportunities for social and economic empowerment, Syrian, Arab, and international organizations held a conference aimed at enabling investment in northern Syria. The conference recommended forming working groups to visit UN and international donor organizations and establishing an economic empowerment fund.

In northeastern Syria, the Autonomous Administration raised fuel prices: the price of diesel for agriculture reached /1,050/ SYP, heating diesel reached /1,150/ SYP, and a jar of domestic gas rose to /153,000/ SYP. Additionally, the price of a bread bundle increased from /900/ to /1,400/ SYP after the price of flour sold from mills to ovens was raised in all regions of northern and eastern Syria. In Manbij, the People's Municipality completed the first phase of equipping the industrial city, the largest of its kind in northern and eastern Syria, which will include shops and factories for the food, wood, and metal industries. The Autonomous Administration also concluded a deal with the Assad regime, obliging the supply of half a million tons of wheat at /36/ US cents per kilogram, while the administration priced the purchase of wheat from local farmers at /31/ US cents per kilogram. This deal is expected to yield financial gains for both parties: the regime will acquire wheat without incurring supply and storage costs, and the Autonomous Administration will achieve a profit rate of at least /3/ cents per kilogram of wheat, securing funds to cover the salaries of its civil and military employees.

Meanwhile, the regime government raised fuel prices: gasoline octane 90 reached /12,500/ SYP per liter, octane 95 rose to /14,368/ SYP per liter, and free diesel reached /11,996/ SYP per liter. The Economic Committee of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers called for a tax of /$25/ per imported solar panel. The Ministry of Internal Trade imposed new taxes on imported items, including white sugar and solar panels. Prices of commodities, vegetables, and fruits in Damascus increased by /70%/ compared to the same period last year, yet the regime resumed exporting vegetables and fruits to Gulf countries. The decisions to raise fuel prices and increase taxes have driven up consumer goods prices amid low purchasing power and a deteriorating economic situation, with many families relying on cash transfers from relatives abroad to meet basic living needs.

At the 8th Brussels conference, donor countries pledged /€7.5/ billion in donations, grants, and loans: /$3.8/ billion for 2024 and /$1.3/ billion for 2025. However, concerns about potential funding cuts and reduced aid highlight the urgent need for actors in political, humanitarian, relief, and development sectors to address these challenges through policies focused on economic empowerment and developing response and recovery plans aligned with new challenges.

Indicators of Early Economic Recovery in NW Syria in 2023

Executive Summary

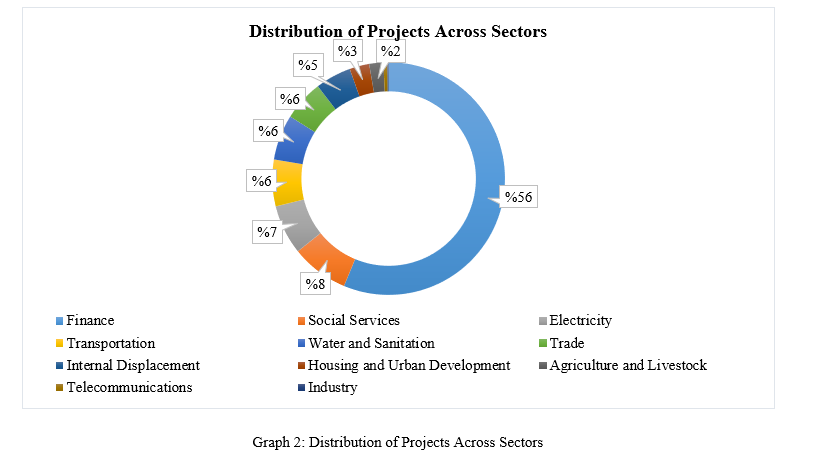

- Throughout 2023, northwestern Syria, particularly Aleppo and Idlib provinces, witnessed the implementation of 5,178 projects. The finance sector was in the lead registering 2,914 projects, followed by 413 projects in social services sector. The electricity sector accounted for 357 projects, transportation and communications for 338 projects, and water and sanitation services for 327 projects.

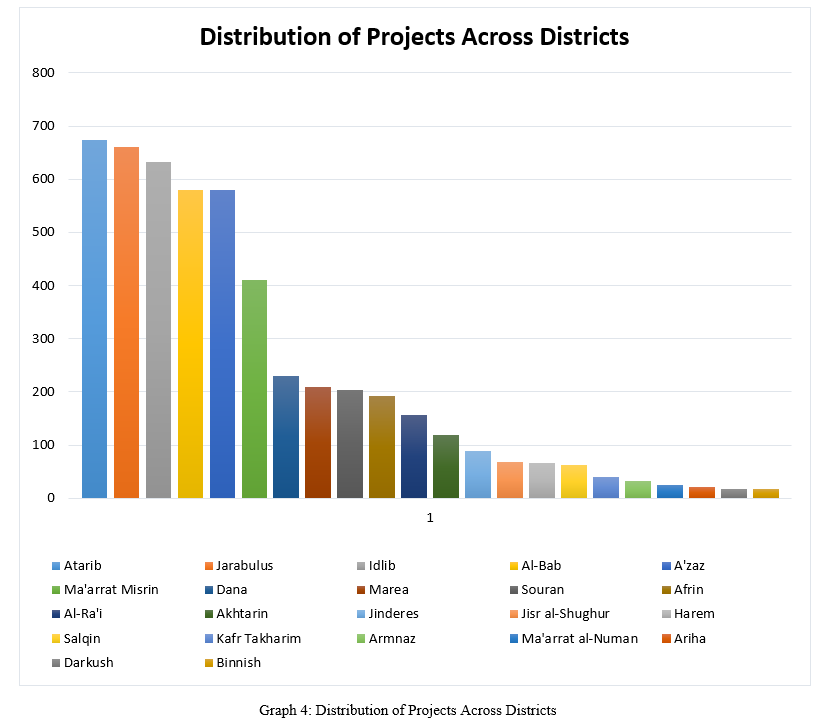

- Approximately 68% of these projects were conducted in rural Aleppo. Atarib was the most active locality, followed by Jarablus with 661 projects, and Idlib with 636 projects.

- Following the catastrophic earthquake that struck Syria and Turkey on February 6, 2023, local councils and organizations swiftly moved beyond the initial shock. They managed to carry out diverse projects across various sectors, demonstrating the resilience of the local community in challenging circumstances.

- Efforts were focused on social services and internal displacement sectors to address the earthquake's impact and meet the needs of displaced populations. This included reconstructing schools and hospitals and establishing new facilities to improve living conditions and integrate displaced individuals into new communities.

- The agriculture and livestock sector continues to face significant challenges due to drought, rising cost of raw materials, and the migration of farmers. These issues make agricultural activities non-viable, reduce productivity, and threaten food security.

- The industrial sector faces numerous challenges, including the lack of essential legal documents such as establishment certificates, customs declarations, and health certificates. Additionally, high raw material and energy costs, along with marketing obstacles, further complicate the situation.

- The report proposes several measures and recommendations, including expanding efforts in the finance sector by supporting medium-scale and innovative projects that can drive production, generate employment opportunities, and increase income levels. It advocates for reduced electricity rates for factories to enhance the resilience and competitiveness of local products. Furthermore, it suggests offering financial and material incentives to manufacturers, removing marketing barriers, and broadening access to financial systems to stimulate industrial production and commercial activity.

The report faces a series of technical and research challenges, such as intermittent military tensions in Idlib and rural Aleppo, which directly threaten the "early recovery" process by delaying or halting project implementation. The absence of a statistical institution capable of collecting and organizing necessary data and providing accurate figures forces researchers to rely on monitoring activities conducted by organizations and local councils, a method that may lead to discrepancies in evaluating the recovery level.

Additionally, researchers encounter challenges due to the lack of comprehensive documentation of all activities by local councils and organizations on their official platforms due to security reasons. Moreover, there is a complete absence of data covering the private sector’s activities in the area, adding complexity to understanding and evaluating the full economic situation. It is also worth mentioning the ongoing controversy surrounding the funding of early recovery activities by the international community, which perceives such funding as potentially empowering the regime and contributing to reconstruction efforts. This could lead to the regime exploiting international recovery funds and politicizing them. Furthermore, there is a notable deficiency in international funding for recovery compared to funding for humanitarian needs.

This report defines "early recovery" based on several periodic reports by Omran Center since 2019. The concept refers to the efforts and projects conducted by governance bodies and non-governmental organizations aimed at rebuilding and enhancing economic and social capacities in the aftermath of a conflict. It helps bridge the gap between the humanitarian aid phase and the reconstruction phase, all in pursuit of achieving sustainable stability in a fragmented society and reducing dependency on external assistance.

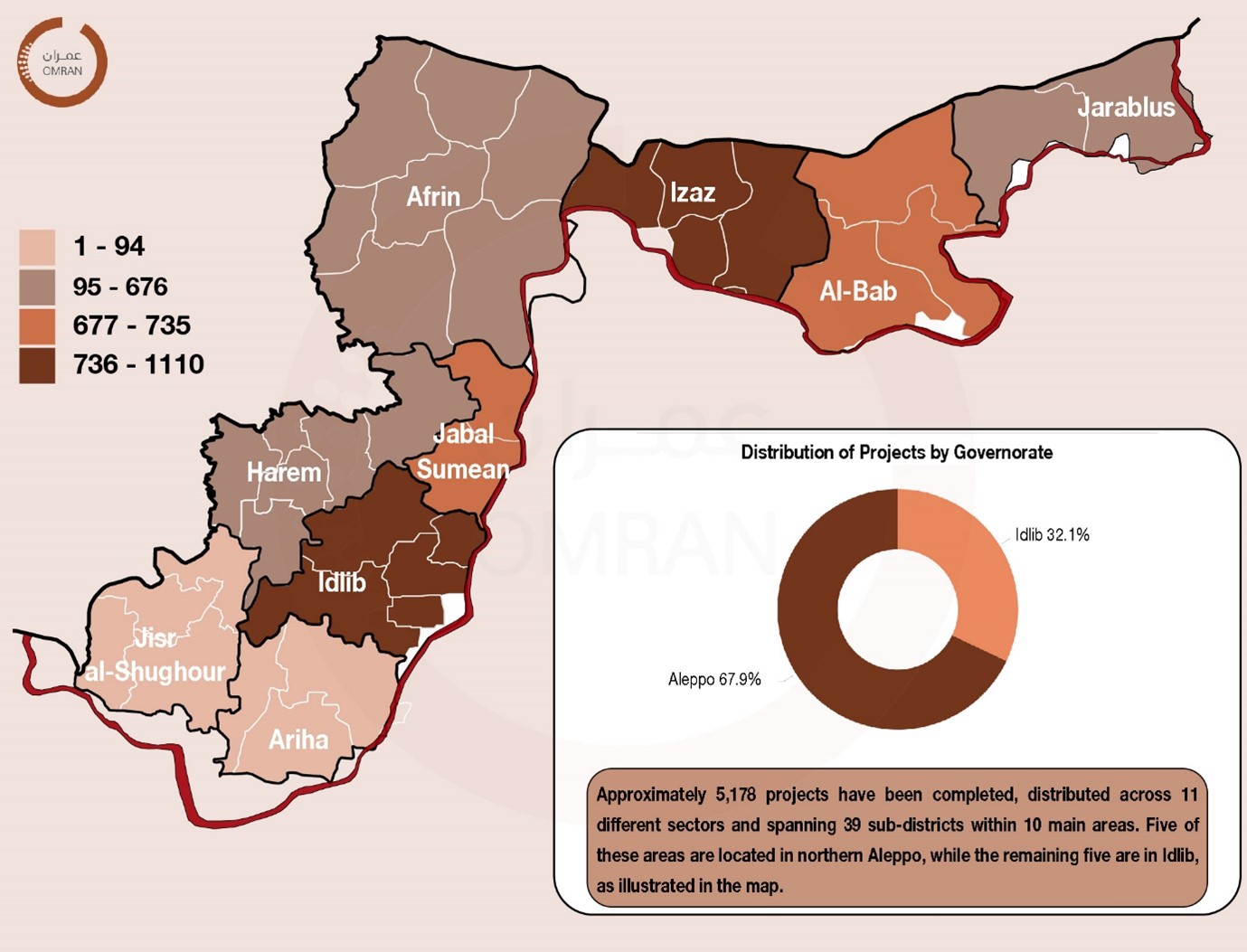

A Comprehensive View of Achievements in 2023

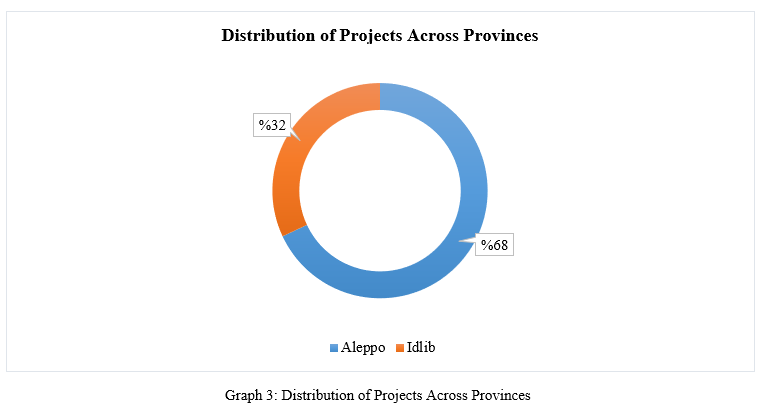

In 2023, northwestern Aleppo and Idlib provinces, governed respectively by the Syrian Interim Government and the "Syrian Salvation Government," witnessed the implementation of 5,178 projects, as indicated by the map below. This represents a 10% increase compared to the previous year, 2022.

The finance sector was the most active, realizing 2,914 projects, followed by the social services sector with 413 projects and the electricity sector with 357 projects. The transportation and communications sector, along with water and sanitation, also saw significant activity, with 338 and 327 projects respectively. Meanwhile, the trade sector executed a total of 292 projects.

The data shows that rural Aleppo accounted for the largest portion of executed projects, with 68% (3,518 projects), compared to 32% (1,661 projects) in Idlib. This indicates a concentrated focus on developmental efforts in rural Aleppo over Idlib.

A deeper look into the distribution of projects across various regions and districts reveals that Atarib was the most active locality, followed by the cities of Jarablus, Idlib, A'zaz, and Al-Bab, as shown in Figure 4. The geographical concentration of projects in certain areas can be attributed to multiple factors: the presence of organizations in these districts, high population density, and large displaced populations, which increase the need for humanitarian and developmental projects. Additionally, favorable conditions for implementing projects in terms of security, available infrastructure, labor force, and proximity to logistical support centers further facilitated project implementation.

Among the significant events of 2023 that impacted the "early recovery" process was the devastating earthquake on February 6, 2023, which struck 137 cities and towns in rural Aleppo and Idlib, affecting over 1.8 million people, causing the deaths of 4,540 civilians, injuring about 12,000 individuals, and leaving 67 people missing. The disaster prompted the displacement of approximately 300,000 people, predominantly children and women. The earthquake also resulted in material losses, including the destruction of 433 schools and 73 health facilities, and the complete destruction of 1,867 buildings, with 8,731 homes and buildings partially damaged, according to figures from the "Support Coordination Unit".

In response to the earthquake, prominent organizations announced the formation of a "Joint Operations Alliance" consisting of "The Syrian Forum," "The Syrian American Medical Society," and "The Syrian Civil Defense" to coordinate efforts in addressing the disaster. Additionally, the Qatar Development Fund pledged support for the construction of a comprehensive city to shelter 70,000 people in northern Syria.

Economically, the transit fees for traders entering Turkish territories increased from $2,200 to $5,000 annually, which may impose financial burdens on traders and industrialists, potentially Shrinkage industrial and commercial businesses. A commercial court was established in Sarmada, Idlib, aimed at resolving commercial disputes among traders registered with the chambers of trade, covering intellectual property, bankruptcy, disputes related to commercial papers, currency exchange, commercial remittances, and banking activities.

Local councils in rural Aleppo seek alternatives for providing power at reasonable prices amidst the increasing suffering of residents and entities from rising electricity prices. They threatened electric companies to terminate contracts and applied increasing pressure, resulting in reduced subscription fees to 2.77 Turkish lira for homes and 3.17 TL for commercial in Jarablus, Afrin, and A'zaz, down from 4.24 TL for homes and 5.75 TL for commercial.

The Ministry of Finance in the Interim Government launched the first investment conference, aiming to develop the region, contribute to improving living standards, and increase employment opportunities. The Interim Government and the "Syrian Salvation Government" set the price of durum wheat at $330 per ton and soft wheat at $285 per ton, which is $100 less than the pricing in the "PYD" area, while the price in areas controlled by the regime is $222. Lastly, fluctuations in the Turkish lira negatively affected economic life and significantly slowed down commercial activity in Idlib and rural Aleppo.

A Look at the Sectors of Early Economic Recovery

In 2023, organizations implemented 2,914 projects within the finance sector, focusing particularly on areas such as A'zaz, Jebel Saman, Jarablus, Idlib, and Al-Bab, which saw the highest number of projects. The significant emphasis on the finance sector is due to the continuous operations of the “Hayat Fund,” “Syria Recovery Trust Fund,” and other organizations involved in direct cash interventions.

The growing interest in the finance sector plays a pivotal role in stimulating the economic recovery of the area by providing the necessary liquidity and supporting small and medium-sized enterprises, which in turn contributes to job creation and increases productivity. It also enhances social stability by enabling residents to improve their financial income, reduce poverty, diversify income sources, and reduce dependency on humanitarian aid and economic activities, increasing their resilience to economic shocks. Moreover, it develops the financial infrastructure of the area through the establishment of financial institutions capable of offering diverse financial services, encourages innovation, and entrepreneurship to develop emerging projects.

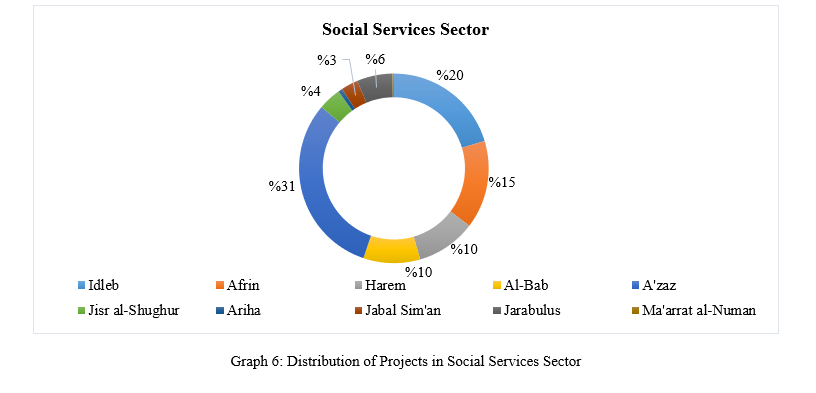

In the social services sector, 413 projects were implemented during 2023, marking an increase compared to previous years. This increase is primarily attributed to the urgent need to rehabilitate the health and education infrastructure severely damaged by the devastating earthquake on February 6. Organizations concentrated most of their budgets on repairing schools, hospitals, and public facilities such as bakeries, markets, and shops, which were either completely or partially damaged. New schools and hospitals were established, including Amanos University in Afrin, which encompasses several departments such as the College of Health Sciences, Nursing, Anesthesiology, Laboratory Analysis, and Radiography. This step underscores the critical importance of education in the processes of recovery and social rebuilding. Additionally, the removal of debris and damaged buildings continued, as civil defense teams executed a three-phase earthquake response plan. The first phase involved emergency response to search for survivors and retrieve the bodies of victims, clearing roads, securing risks from collapsing walls, and finally, debris removal.

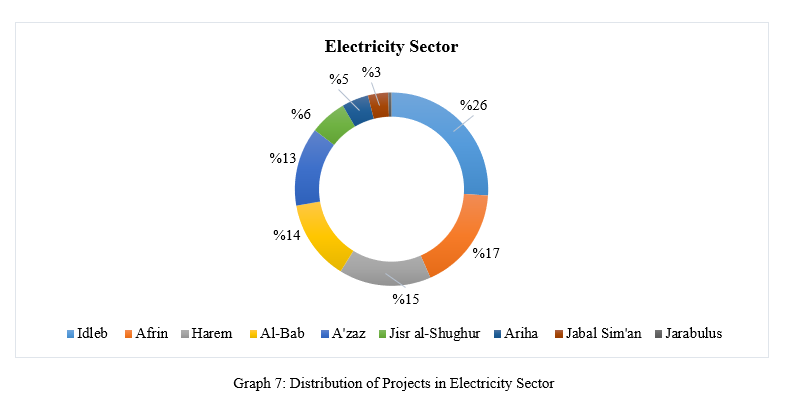

357 projects were implemented within the electricity sector, particularly in Idlib, A'zaz, and Afrin. These projects included the rehabilitation of the electrical infrastructure through the maintenance of electric poles and transformers, the preparation and maintenance of medium and low voltage power lines, the installation of meters, and the extension of cables. The projects also included street and residential area lighting. Moreover, the reliance on renewable energy continued as organizations installed solar power systems for schools and hospitals, reflecting the pursuit of sustainability and the reduction of dependence on traditional energy sources.

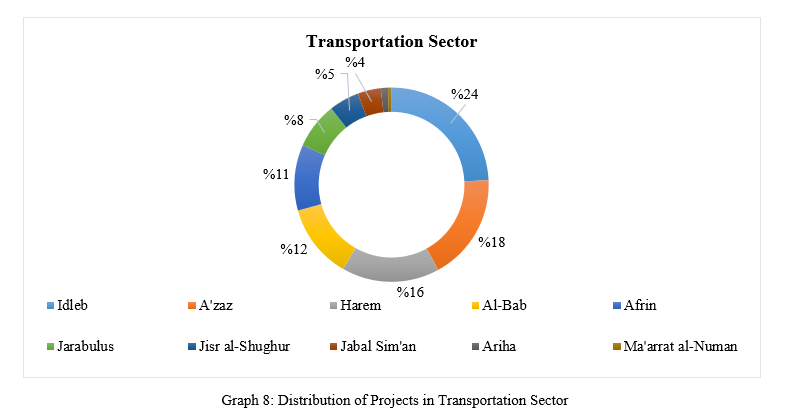

The transportation sector saw 338 projects, with Idlib, A'zaz, Harem, Al-Bab, and Afrin being the areas with the most projects completed. The continuous focus on these projects aimed at improving the infrastructure of roads in vital areas, reflecting the importance of the road network between cities and towns. This focus plays a pivotal role in facilitating the movement of goods and individuals, enhancing the connections between communities and markets, improving access to essential services, and bolstering the ability to reach educational and healthcare services. Among the main roads paved are: the international road connecting Idlib with Bab al-Hawa, the eastern corniche road in Ma'arrat Misrin spanning 800 meters, the road between Darkush and Ain al-Zarqa, the road between Kafr Karmin and Atarib, the road between Sarmada and Harem stretching 9,500 meters, and the third Afrin bridge, which is 1,650 meters long.

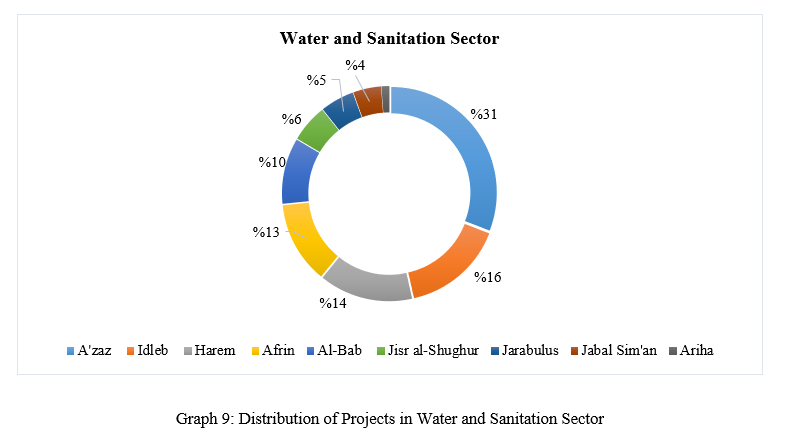

Within the water and sanitation sector, 327 projects were implemented. One of the most prominent projects in this sector was the inauguration by the Syrian Interim Government of a solar energy system for drinking water pumping stations in Al-Bab. This project, costing an estimated 2 million euros, has a production capacity of 1.15 megawatts, making it the largest service project of its kind. It utilized 2,547 solar panels to serve approximately 200,000 residents in Al-Bab, supported by the “Syria Recovery Trust Fund.” The use of solar energy to operate water pumping stations represents a major effort towards transitioning to renewable energy sources and environmental sustainability.

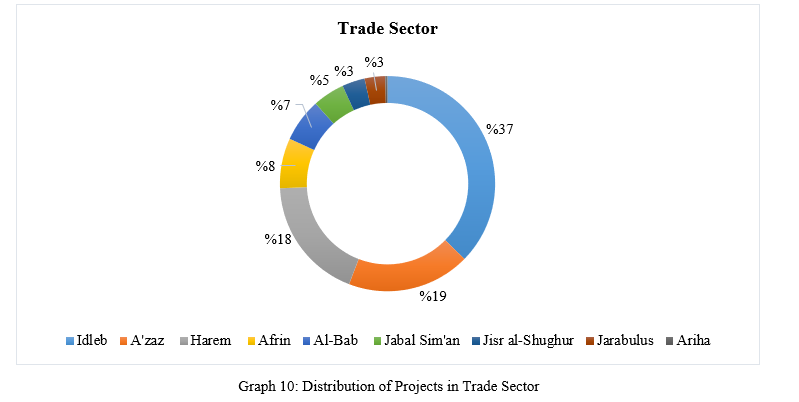

The trade sector saw approximately 292 projects implemented, with the majority concentrated in Idlib, reflecting its significance as a major commercial hub in the area. The projects executed in this sector encompassed a range of economic and service activities, including the tender contracts issued by organizations to supply various goods and execute various services. These included the supply of water, diesel fuel, electrical and medical equipment, book printing, stationery, and communication equipment, as well as car rental and other essential services. The reliance on tenders as a mechanism for implementing these projects enhances the standards of transparency and efficiency in selecting the best offers, thereby maximizing the possible value from available resources. It also facilitates cooperation between international and local organizations and the private sector, thereby strengthening the role of partnerships in the economic recovery process.

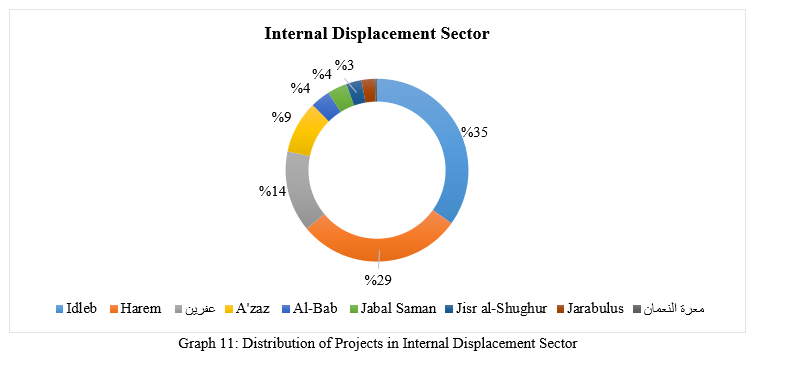

In the internal displacement sector, 256 projects were implemented, with a focus on Idlib, Harem, Afrin, A'zaz, and Al-Bab. These areas host the largest displaced populations and have become focal points for implementing projects aimed at improving infrastructure and living conditions for the displaced. The projects executed covered various aspects of essential services within the camps, including paving roads with gravel to facilitate movement and access, extending sewage networks to ensure sanitation and public health, and renovating homes to provide safer and more comfortable shelters.

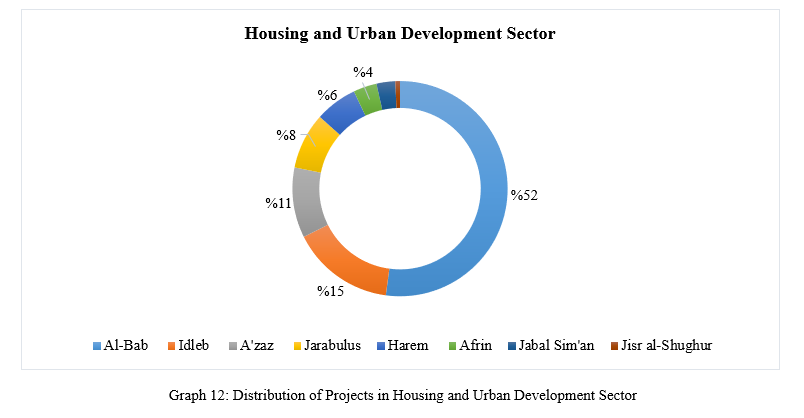

In 2023, 142 projects were carried out in the housing and construction sector, with the city of Al-Bab leading with 74 projects, as seen in previous reports, due to the common licensing granted for the construction of residential and commercial buildings. Organizations established several residential complexes aimed at improving living conditions for people residing in camps by relocating them to new buildings equipped with all essential services. These include the Al-Salam Complex, the third Al-Bonyan Residential Complex, and the villages of Rahma, Balsam, Al-Nasr, Qa'rqalbin, and Rawafid Al-Khair. The continuation of these projects is intended to alleviate the pressure on overcrowded camps and provide a relatively better living environment for the IDPs.

In the agriculture and livestock sector, 102 projects were implemented with notable support from the “Syrian Recovery Trust Fund.” This included the launch of an agricultural project aimed at supporting farmers in the cultivation of irrigated wheat over an area of 2,000 hectares, spread across towns and cities such as Al-Ghandoura, Al-Ra'i, Bza'a, Marea, and A'zaz. The Humanitarian Relief Authority provided support to 950 wheat farmers in Northern Rural Aleppo by supplying necessary agricultural inputs such as wheat seeds, superphosphate fertilizer, urea fertilizer, and diesel for irrigation, along with cash vouchers covering the costs of farming, irrigation, and harvesting. These efforts reflect a commitment to enhancing food security and supporting the local economy through the development of the agricultural sector, which is a fundamental pillar for the economic recovery of the region. It also contributes to creating job opportunities for farmers and enhancing their resilience against economic challenges. The importance of agricultural projects as drivers of economic growth and stability in rural communities is highlighted through the provision of resources and technical support to farmers, enabling them to improve their productivity and the quality of their crops, leading to self-sufficiency and reduced dependency on food imports.

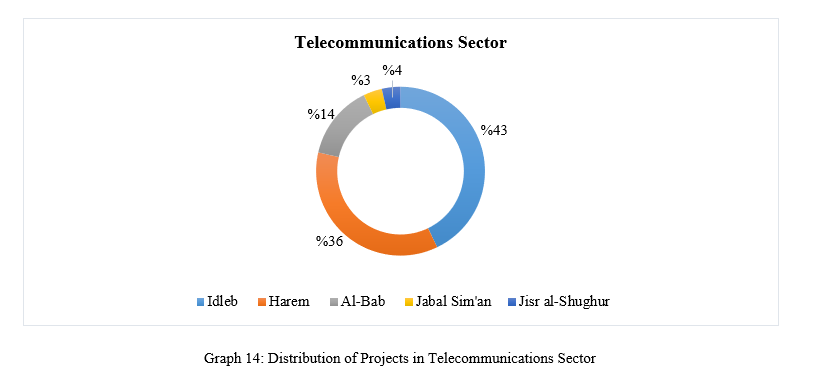

In the telecommunications sector, 28 projects were implemented, including improving and expanding the telecommunications and internet infrastructure. Key projects featured the maintenance of main and subsidiary cables in the town of Binnish, with capacities of 450 lines for the main cable and 550 for the subsidiary, and the expansion of a subsidiary network for landline and internet services on Thalatheen Street in the city of Idlib. Additionally, the university communications center underwent expansions to the landline and internet networks to cover new areas such as Douar Al-Fallahin, along with extending internet cables throughout the city streets. The "Syrian Salvation Government" also launched mobile telecommunication services under the name SYRIA PHONE. This project represents a step towards enhancing communication services in Idlib. Providing strong and reliable communication networks is essential for achieving economic and social development, as it opens new prospects for education, business, and online services.

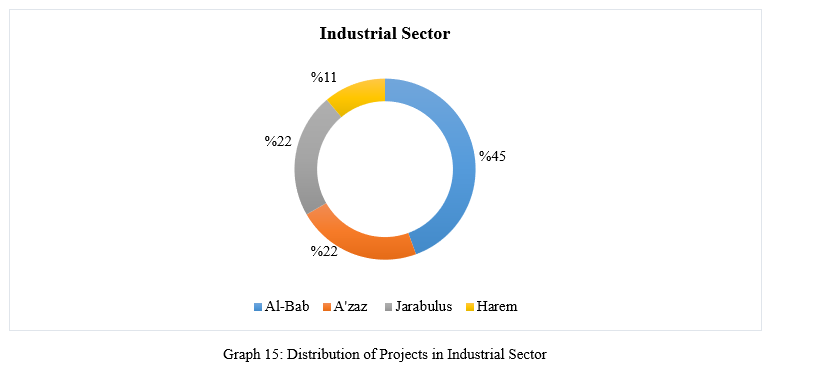

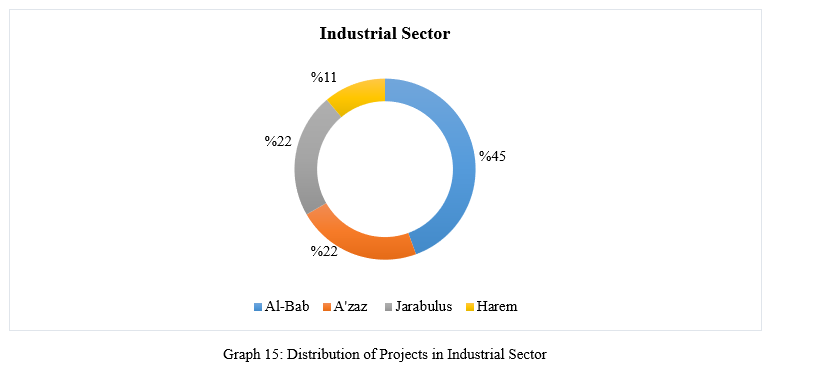

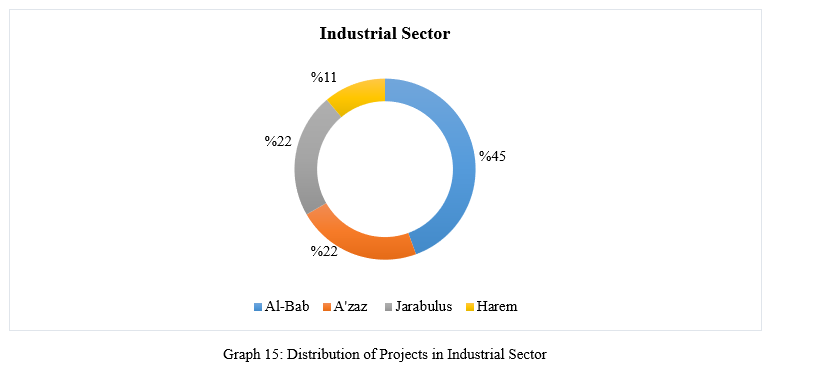

Finally, in the industrial sector, nine industrial projects were implemented in the area. Among these projects were the establishment of a factory for producing powdered infant milk in the industrial area of Al-Ra'i, a diaper production facility in Jarablus, and the first iron and profile production factory. Additionally, a cement factory in Al-Ra'i and an Indomie factory in the industrial city of Bab al-Hawa were established. Efforts were also made to complete the industrial city in A'zaz and to open the industrial city in Marea. Despite the industrial sector being a key pillar in recovery and a vital part of the economic stability strategy, which reduces dependence on imports and enhances competitiveness, the region still faces significant challenges that hinder the development of the industrial sector.

Results and Recommendations

The report addresses the efforts of early economic recovery in northwest Syria during 2023, focusing on the activities of local councils and organizations across 11 sectors. It covers improvements in sectors such as finance, agriculture, trade, and services, in addition to ongoing challenges in infrastructure and economic stability. From the data presented in the report, several conclusions related to recovery efforts in the region can be drawn, including:

- Overcoming the Earthquake's Effects: Despite the extensive destruction caused by the earthquake, the area managed to implement approximately 5,178 projects, underscoring the local community's resilience and recovery from the disaster's shock. The continuation of projects by local councils and NGOs contributes to the gradual transition from relief and humanitarian aid to early recovery. In this context, it is crucial to expand advocacy efforts to attract the attention of the international community and donors towards recovery, highlighting the importance of projects in all sectors and achieving economic and social stability in the area.

- Enhancing the Role of the Finance Sector: The finance sector played a significant role in supporting the early economic recovery process in 2023, providing job opportunities and diversifying household income sources. Financing small and medium-sized projects and providing direct financial support to families will contribute to economic independence and job creation. To ensure sustainability and optimal impact, it is essential to develop effective monitoring and evaluation systems and establish training programs to enable beneficiaries to manage their projects successfully.

- Improving Infrastructure: Projects implemented in the transportation, communications, water, and sanitation sectors played a pivotal role in supporting the area's economic recovery, particularly in road repairs and improving water supplies. However, challenges arising from population density and ongoing shelling targeting infrastructure, alongside drought issues, necessitate a more significant international effort in these sectors.

- Supporting Agriculture and Livestock: The agriculture sector faces complex challenges due to drought, rising raw material prices, labor migration, and reduced profitability of agricultural activities due to obstacles in exporting and marketing products. To address these challenges, it is crucial to support this sector by providing subsidized seeds, feed, equipment, and pesticides to reduce production costs, enhance crop marketing, integrate crops into food industries, and develop initiatives to promote them in foreign markets.

- Stimulating Industrial Growth: Providing a stable environment will attract significant investments and facilitate the operations of existing factories and workshops in the area, encouraging industrialists to relocate their operations from areas adjacent to Turkey to rural Aleppo and Idlib. This can only be achieved through reducing electricity prices, offering material and financial incentives to manufacturers, developing effective marketing and export strategies, and accessing the international financial system more extensively.

- Encouraging Small and Medium Enterprises: Given the current economic situation, it is essential to focus on developing workshops and small and medium-sized projects in the region, particularly in technical and computing fields, which are characterized by their flexibility, adaptability, and potential for marketing beyond borders.

- Addressing the Shortage of Humanitarian Aid Funds: Given the shortage of humanitarian aid funds from the international community, the region faces an urgent challenge that calls for adopting diverse and innovative financing strategies to achieve a degree of economic independence. Therefore, governance bodies and organizations should enhance investment tools, build a private sector and financial institutions, and conduct advocacy campaigns in expatriate countries to gather the necessary funding to implement economic plans.

In conclusion, the Interim Government, Local Councils and non-governmental local organizations managed the recovery phase with reasonable effectiveness in terms of resources, governance, and organization, despite the severe crises experienced in the region, especially the earthquake disaster on February 6, 2023. The implemented projects played a pivotal role in driving early economic recovery and ongoing development since the relative stabilization of the region after the years 2016 and 2018. However, there is an urgent need to develop an effective mechanism for an overall economic plan for the entire region (synchronized with other regions) that ensures the adoption of a specific economic model based on well-considered decisions and policies. This plan should address profound challenges such as the crisis of missing legal documents, water, electricity, industry, the financial environment including currency, pricing, and financial institutions, improving conditions for the displaced, and establishing a comprehensive legal framework to deal with vital issues and casesTop of Form.

Early Recovery Trust Fund in Syria: A Technical Approach With Political Implications and Associated Risks

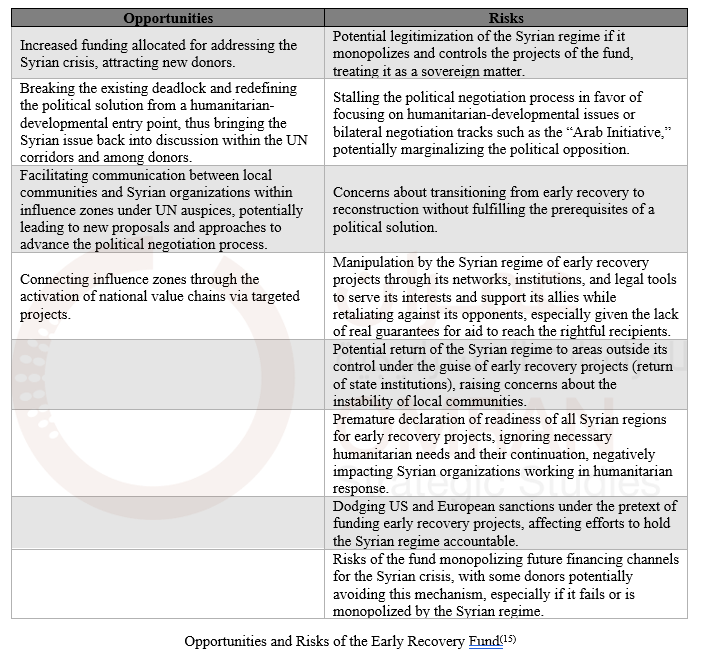

The topic of early recovery is currently a focal point among UN circles and donor entities, as well as among Syrian parties, individuals, institutions, and organizations. In this context, the United Nations, through the Office of the Humanitarian Coordinator in Damascus, announced its approach to establishing an Early Recovery Fund. This announcement has been accompanied by leaks and rumors regarding the fund, its operational mechanisms, and its funding size. Additionally, the announcement has sparked reactions and discussions among donors and Syrians alike. This situation necessitates an initial analysis of this proposal, examining the opportunities it presents and the risks it entails, ultimately leading to recommendations that could guide the fund's operations and ensure the achievement of its intended goals.

Early Recovery: A Problematic Concept and a Syrian Perspective

The concept of early recovery in post-conflict areas is highly debated within humanitarian circles, NGOs, and among donors, primarily due to the absence of a standardized recovery framework for post-conflict scenarios. This gap contrasts sharply with the well-established frameworks for post-disaster recovery. The varying perspectives and distinct demands of stakeholders on early recovery in Syria contribute to its dynamic nature, and continuously shaped by both political and humanitarian considerations throughout the stages of conflict. This puts forward a unique opportunity for Syrians to develop an approach that reflects their specific realities in a more holistic methodology.

In 2008, the United Nations Early Recovery Cluster published its initial Guidance Note on Early Recovery, defining it as "a multidimensional recovery process initiated from a humanitarian context, guided by development principles aimed at leveraging humanitarian programs to foster sustainable development opportunities. The objective is to cultivate self-reliance mechanisms, uphold national ownership, and ensure resilience throughout the post-crisis recovery phase. This process includes the restoration of all essential services such as livelihoods, shelter, governance, security, rule of law, and environmental and social dimensions, with a particular focus on the reintegration of displaced populations(1)Also, TheGlobal Cluster for Early Recovery (GCER) offered an expanded definition, describing early recovery not merely as a phase but as “a thorough, multidimensional process that commences early in the humanitarian response. It focuses on bolstering resilience, restoring, or enhancing capacities, and addressing enduring issues that contributed to the crisis rather than exacerbating them, alongside a suite of programs designed to aid the transition from humanitarian relief to development.(2)While The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) characterized early recovery as “an approach that meets recovery needs emerging during the humanitarian phase of an emergency, where saving lives remains a critical and immediate priority. Early recovery initiatives support affected communities in safeguarding and reinstating essential systems and service delivery, building upon initial response efforts, and establishing a foundation for prolonged recovery. The outcomes of these early recovery efforts include creating robust foundations for resilience post-crisis, fostering sustainable development solutions led by national or local entities, and rebuilding community capacities(3).

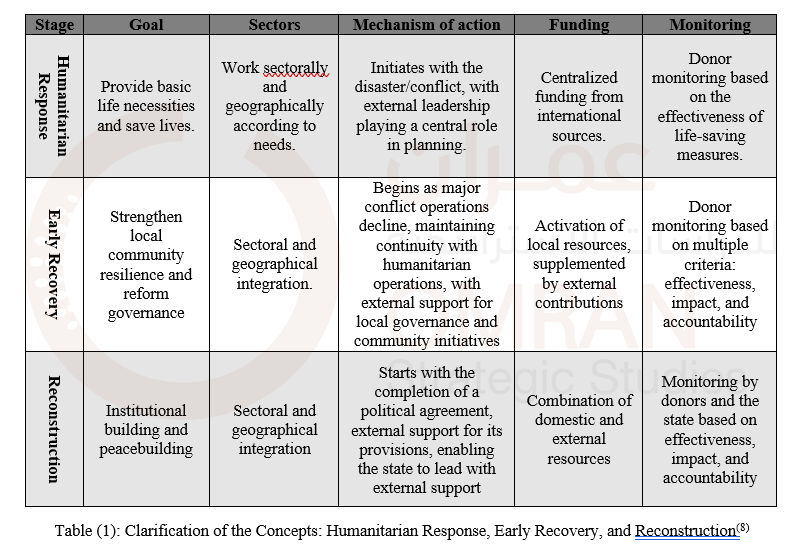

From these definitions, it is evident that Early Recovery is a multidimensional approach that builds on humanitarian response, aiming to stabilize communities and enhance their adaptive capacities. However, there is debate about the content and scope of early recovery. De Vries and Specker argue that early recovery is a period between the humanitarian phase during and immediately after a conflict and the medium to long-term development phase. While some researchers and humanitarian agencies define the first three years after the end of a conflict as the timeframe for early recovery, according to the UNDP program, early recovery can begin even before the conflict parties reach a political settlement(4).

Early recovery in post-conflict situations is closely associated with the stakeholders involved in recovery and their interests. This makes the transition from conflict to peace not merely a technical approach and practice but a highly political process in which principles, priorities, and concepts vary. This variability is highly evident in the Syrian context and explains the diversity of approaches to this concept. Some argue that the early recovery process should begin once the conflict has ended, in response to attempts by the Syrian regime to initiate this process before achieving a political solution. It aims to establish peace and stabilize “state institutions” through a mix of different policies. There are at least four main threads that form the foundational concepts of “early recovery.(5)

- Humanitarian aid frameworks;

- Economic growth and development;

- Peacebuilding and human security;

- Governance models and state-building.