Rateb

Assad’s Officers’ Companies… Disclosure, Accountability, and Reallocation

Introduction

Following the fall of the Assad regime, a critical opportunity has emerged to conduct thorough and methodical security vetting operations targeting all commercial enterprises. These operations, grounded in official documentation issued by state ministries, aim to uncover companies linked to former regime officers and other human rights violators—whether registered in their own names or under those of family members. The process includes tracing the assets and financial flows of these entities, followed by the freezing of their holdings as a necessary interim measure. This would allow for a comprehensive legal review and the adoption of appropriate decisions regarding their status, ultimately ensuring the protection of national resources and their redirection toward serving the public interest ([1]).

The Assad regime’s security apparatus long sought to maintain strict secrecy around itself. However, this veil of secrecy began to erode following the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, as defections and leaks exposed a significant documents and information. These disclosures made it possible to trace both the formal and informal networks of the regime and to better understand the nature of relationships among its officers—within state institutions and beyond.

Before the regime's collapse, a substantial body of verified data had already been collected—particularly concerning officers under international sanctions([2]). The findings revealed that many of these individuals owned companies operating across various sectors, either directly or through relatives. This stands in clear violation of the previous Military Service Law, which explicitly prohibited voluntary military personnel from engaging in commercial activities, whether directly or by proxy. These findings suggest that some of these companies may have been established under official direction, as part of a systematic exploitation of power for personal gain or to serve the interests of the regime itself ([3]).

This paper seeks to establish a framework for addressing commercial activities linked to officers of the Assad regime and their family members. It does so by analyzing the motivations behind the creation of these enterprises and the objectives they were intended to serve. In addition, the paper outlines proposed future measures—including asset freezes and the redirection of resources toward national development. It also includes case documentation of several companies involving relatives of officers implicated in human rights violations.

Notably, the establishment of these companies was not merely a response to temporary economic hardship. Rather, it was driven by a combination of factors aimed at securing personal financial interests for regime officers and generating alternative revenue streams to sustain the regime amid declining official resources and mounting sanctions pressure. These companies also formed part of a broader strategy to ensure the continuity of power—by circumventing sanctions and reinforcing the regime’s intertwined networks of economic and security influence.

The Economic and Strategic Objectives Behind Establishing These Companies

The companies linked to regime officers were not merely conventional economic ventures. Rather, they served multiple functions—generating profit, providing protection, and advancing the regime’s security interests. This is evident in a set of underlying objectives :

Money Laundering

The scale of violations and crimes committed by the Assad regime—through its officers and security personnel—is no longer in question. These abuses extended far beyond systematic killing and torture to include widespread financial extortion and the imposition of informal levies, including the blackmail of detainees’ families. Such practices became a primary source of income for regime officer([4]).

These commercial enterprises played a significant role in laundering money under a legal veneer on behalf of regime officers. The funds laundered through these companies stemmed from a range of illicit sources—including extortion, bribery, administrative and financial corruption, and the systematic looting of abandoned cities, commonly referred to as “area custodianship” following the forced displacement of residents. This also included proceeds from smuggling operations conducted both within and beyond Syria’s borders, as well as from the drug trade—particularly captagon—which has become one of the regime’s most prominent sources of illicit financing.

Monopoly and the Elimination of Competitors

These companies contributed to consolidating monopolistic control over state-linked contracts and tenders, with security influence playing a pivotal role in awarding such deals to businesses owned by regime officers or their commercial fronts. Competing firms were systematically excluded, enabling these companies to reap enormous profits at the expense of public resources—under a legal framework that appeared procedurally sound.

The pervasive lack of financial transparency—both within these companies and across state institutions—further obstructed access to reliable data on executed contracts, significantly limiting efforts to trace transactions or hold those involved accountable.

Security Dimensions of Concealment

The establishment of some of these companies served clear security objectives—namely, concealment and operating on behalf of the regime. Certain contracts with state institutions, particularly those involving security agencies, required the involvement of front companies that maintained a high degree of apparent credibility. This structure enabled the concealment of direct ties between these entities and security institutions, allowing them to evade sanctions by exploiting the lack of detailed knowledge about such affiliations in several countries.

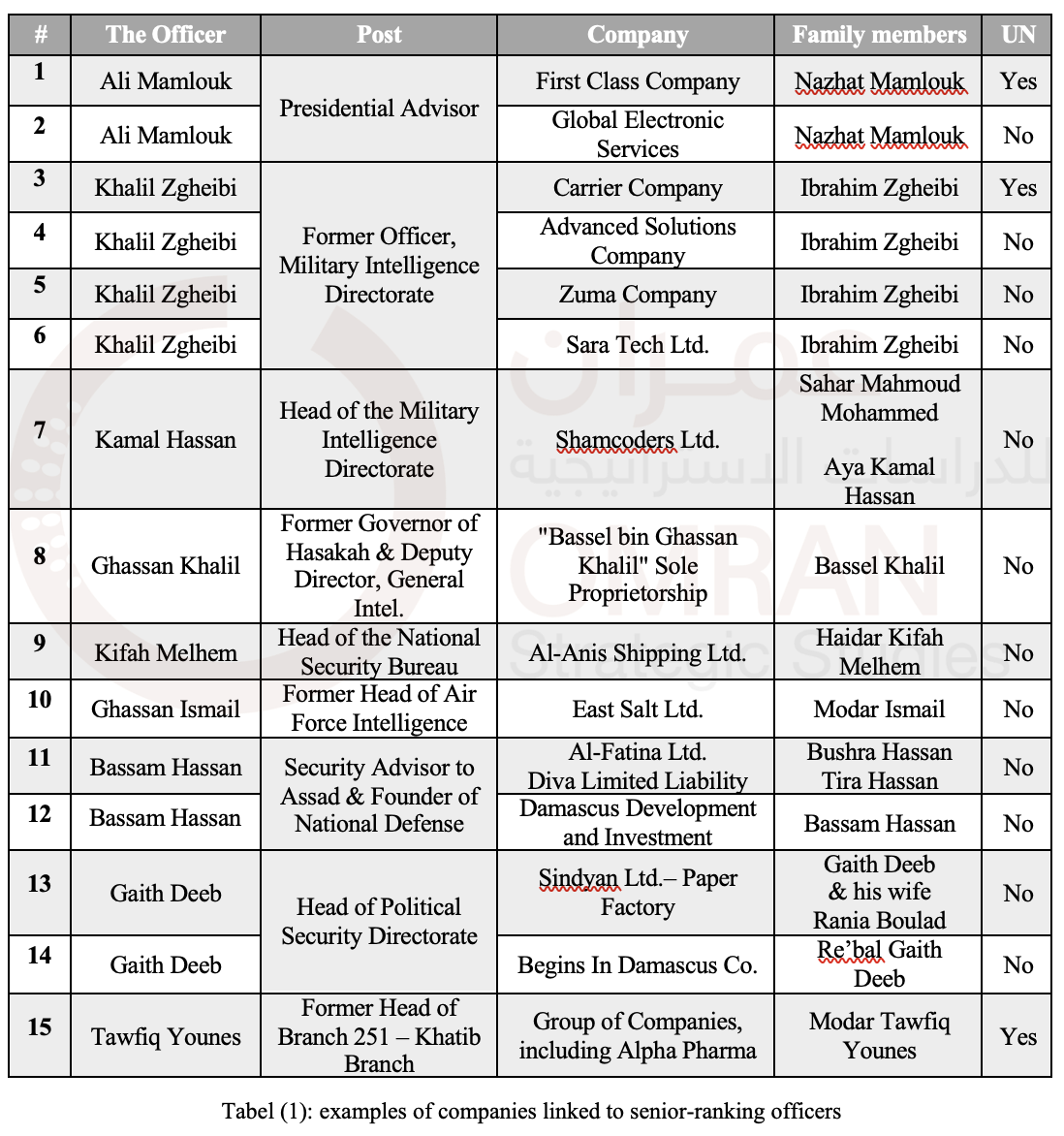

For instance (see appendix), “Sahar Mahmoud” and “Aya Hassan” established a company named ShamCoders, which specializes in software development and technology imports([5]). In reality, the company is owned by the wife and daughter of Major General Kamal Hassan, the long-standing head of Military Intelligence, who has been under U.S. sanctions for years. Those behind the company leveraged this structure to bypass international monitoring and continue their commercial activities out of public view.

Expansion into International Institutions and Circumvention of Sanctions

The activities of regime-affiliated companies were not limited to the domestic market. Many expanded their reach to penetrate international institutions and circumvent sanctions regimes through commercial fronts and complex economic networks that are difficult to trace. These companies engaged in the following practices:

Contracting with International Organizations

A significant number of these companies benefited from United Nations procurement contracts. Several UN agencies purchased supplies or paid for services provided by these firms, despite being aware of their connections to regime security officers. Over the years([6]), these officers exerted subtle pressure on UN agencies and personnel—ranging from implicit threats to direct intimidation, as well as exploiting corruption among certain staff members or leveraging personal relationships with officers.

One notable example is the daughter of Major General Hussam Louka, then-head of the General Intelligence under the Assad regime. She was employed by the UN in Syria([7]), reflecting a broader pattern of security influence embedded within international institutions.

Furthermore, according to UN procurement databases, the organization contracted with companies linked to high-ranking officers from Syria’s security services (see appendix). These include Al Daraja Al Oula (First Class), a company owned by Nazhat Mamlouk, the youngest son of Major General Ali Mamlouk—former head of the National Security Bureau and top security advisor to Bashar al-Assad. Contracts also involved companies owned by the son of Brigadier General Khalil Zgheibi, an officer in the Military Intelligence Directorate.

What is particularly alarming is that the United Nations does not consistently disclose the names of all companies it contracts with in Syria. Some are listed under the generic classification of “unknown vendors.” Statistics indicate that this category accounts for approximately 18.5% of total procurement activities([8]), representing a serious transparency gap and heightening the risk that some of these companies may be linked to suppliers implicated in human rights violations.

Exploiting Reconstruction Projects and Evading Sanctions

Evasion of Western sanctions was a primary driver behind the establishment of these companies. Regime officers often created businesses under the names of relatives or close associates, using them as commercial fronts that made legal accountability significantly more difficult. This tactic complicated the efforts of both the new Syrian administration and international actors seeking to enforce sanctions, as tracking structural changes within these companies or proving their links to sanctioned officers or their family members became increasingly challenging.

Illicit enrichment operations extend beyond companies officially registered in the names of officers or their relatives. They also include expansive networks of commercial fronts operating under the influence and control of these officers. A prominent example is the business empire run by businessman Khodr Ali Taher—also known as “Abu Ali Khodr”—on behalf of Maher and Asma al-Assad, with ties extending to Bashar al-Assad himself and his advisor Yasar Ibrahim. The latter oversees a wide network of companies operating across multiple, intertwined layers of the economy, often with the help of his proxy, Ali Najib Ibrahim([9]).

These economic networks have served as a central tool for the regime to circumvent international sanctions, enabling officers and officials to continue generating vast illicit profits. This strategy allowed the regime to expand its economic reach, secure additional funding to reinforce its core power structures, and mitigate the impact of sanctions by relying on opaque commercial fronts and complex networks that are difficult to trace.

If these commercial activities are not exposed, many of these companies may eventually position themselves to benefit from Syria’s post-war reconstruction projects. By obscuring their direct links to security officers, they could gain access to lucrative contracts—allowing their owners, who played a central role in the country’s destruction by supporting the regime’s military and security approach since 2011, to profit from the rebuilding of the very infrastructure they helped dismantle.

Mechanisms for Uncovering Officer-Owned Companies and Networks

In the wake of the political shifts following the fall of the Assad regime, economic and security investigations have emerged as essential tools for dismantling the financial structures tied to regime officers and influential figures. These investigations are not solely aimed at legal accountability—they also seek to protect public resources and prevent the continued operation of looting networks and exploitative economic structures.

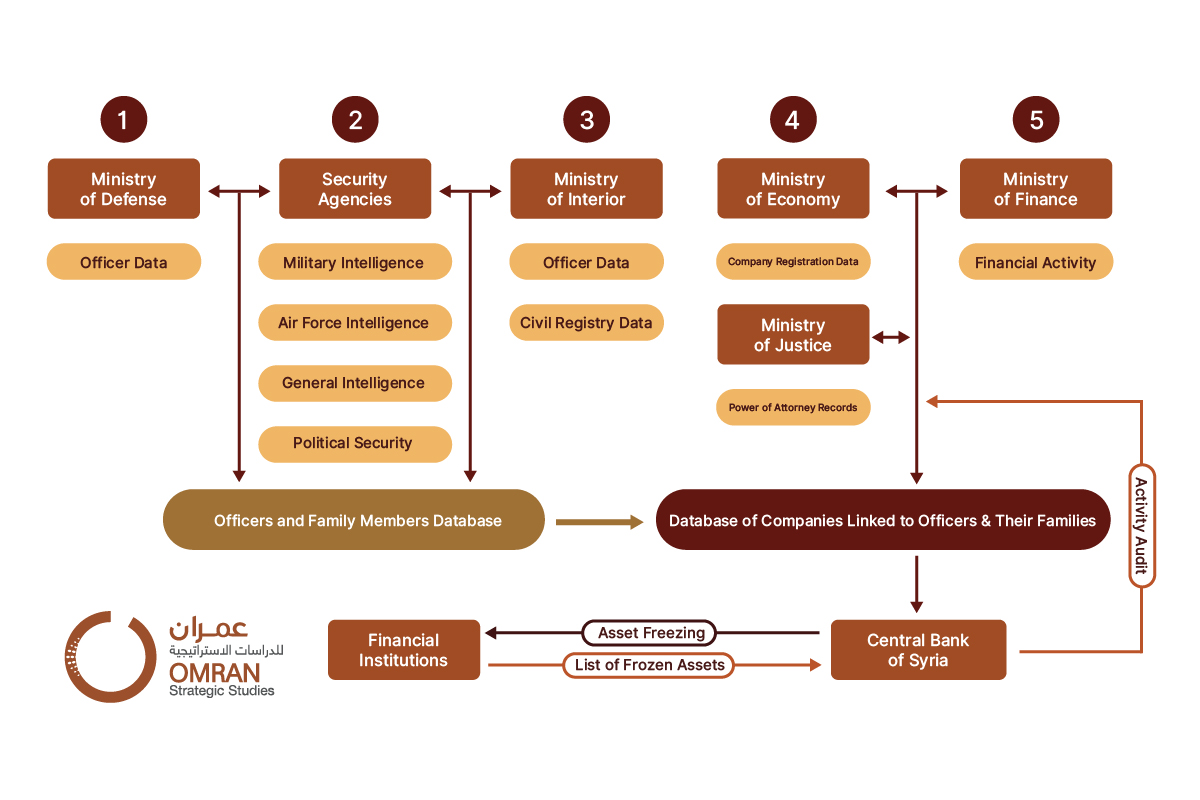

This mechanism begins with the collection of officer data from official databases—particularly those maintained by the Ministries of Defense and Interior, as well as the intelligence services. These entities serve as the primary sources for identifying officers and their official positions.

The next phase involves cross-referencing this information with civil registry records, in order to identify individuals related to these officers, including spouses, children, and siblings. This process enables the construction of a unified database linking officers to their family members, which can then be used to trace companies owned or partially controlled by them—whether directly or through indirect affiliations.

Data held by the Ministry of Economy—specifically the Directorate of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection, which is responsible for issuing business licenses. These names are then matched against the Ministry of Justice’s database to identify any corresponding legal powers of attorney. This intersection of data reveals companies owned by officers or their family members, many of which operate as fronts.

Once these companies are identified, detailed lists are forwarded to the Central Bank of Syria, which is then tasked with freezing their bank accounts and related assets as a precautionary measure, pending further investigation into their activities.

The Ministries of Finance and Economy play a joint role in this process by reviewing the financial and tax activities of the identified companies and investigating any violations or suspicious affiliations. If it is confirmed that these companies are linked to officers implicated in human rights violations—or to their family members—or that legal instruments authorize them to manage or sell assets, the relevant legal procedures are initiated to confiscate these assets in accordance with the state’s established mechanisms.

Figure (1): Mechanism for Identifying Officer-Owned Companies and Networks

This effort requires the establishment of an institutional framework that adopts the proposed mechanism and ensures coordination among relevant ministries and state institutions, drawing on data available in their official records. The objective is to create a unified database of companies registered in the names of officers, human rights violators, and their family members.

The process also necessitates technical and analytical support from specialized research centers with expertise in tracking networks of influence and commercial fronts. In this context, coordination with international bodies becomes essential to facilitate access to assets held abroad and to address the role of cross-border companies used to circumvent sanctions. The significance of this methodology lies in its contribution to transitional justice—through the dismantling of the economic structures underpinning the repressive apparatus and the prevention of their reconstitution in the future.

Future Measures to Determine the Fate of Regime-Affiliated Companies

Addressing the economic activities linked to former regime officers and officials requires a comprehensive strategic approach aimed at dismantling the networks that sustained the regime’s power. Commercial enterprises registered under the names of officers’ relatives or linked to them cannot be viewed as entities separate from the regime’s structure, nor should they be dismissed as “non-relevant” operations. Rather, these ventures operated within political and economic frameworks explicitly designed to reinforce regime control and secure its resources.

Accordingly, once these companies are identified in the initial phase, a series of follow-up measures can be initiated, including but not limited to the following:

Asset Freezing and Investigation of Economic Networks

The first step in addressing the economic activities linked to regime officers is the freezing of suspicious assets held by them and their family members. This measure should be implemented in coordination with international actors such as the United Nations and global financial institutions to ensure that both domestic and overseas assets are included.

It is recommended that a specialized legal and economic unit be established within the government to manage this file and carry out asset freezes effectively.

Reviewing Past Contracts and Projects

Reviewing the contracts and projects that have benefited these companies—particularly those linked to the state or international organizations—is a priority to prevent continued funding of these networks or their participation in future recovery and reconstruction efforts.

It is recommended that the aforementioned committee be tasked with auditing both government and international contracts signed since 2011.

Managing Frozen Assets

A clear and transparent plan must be developed for managing frozen assets in a manner that ensures their reinvestment in national development. Available options include: confiscating the assets and transferring their ownership to the state for use in development projects; restructuring the assets by converting them into productive enterprises that serve the public under government supervision; or redistributing the proceeds from asset sales to support public services such as education and healthcare. Alternatively, these funds could be directed toward reparations programs within the framework of transitional justice.

International Cooperation

The government should coordinate with United Nations agencies and countries supporting Syria’s political transition to ensure that assets located abroad are accurately identified and included in accountability efforts. This coordination may involve requesting technical and legal assistance to trace and freeze concealed assets. It is also advisable to broaden the scope of these efforts to include cooperation with international financial institutions to track financial flows linked to the former regime and ensure they are not used for illicit purposes.

Conclusion

These measures should be embedded within the broader framework of transitional justice, which seeks to achieve accountability and prevent impunity for perpetrators of violations—while focusing on dismantling the networks of corruption and exploitation that served as pillars of the former regime. The transitional phase provides the legal and moral foundation for addressing these companies and their beneficiaries, whether through judicial investigations, asset recovery mechanisms, or economic policies aimed at preventing the reemergence of financial influence rooted in the machinery of repression.

Moreover, integrating these efforts within the framework of transitional justice ensures transparency and accountability, while safeguarding the rights of all parties within fair legal standards. The ultimate goal of this process goes beyond accountability—it also includes protecting public resources and redirecting them toward national development. This requires the adoption of rigorous, data-driven methodologies and comprehensive investigations capable of uncovering companies linked to officers and officials implicated in human rights violations in Syria.

Appendix:

Interactive Figure (1), showcases examples of companies linked to security agencies, the military, and their family members.

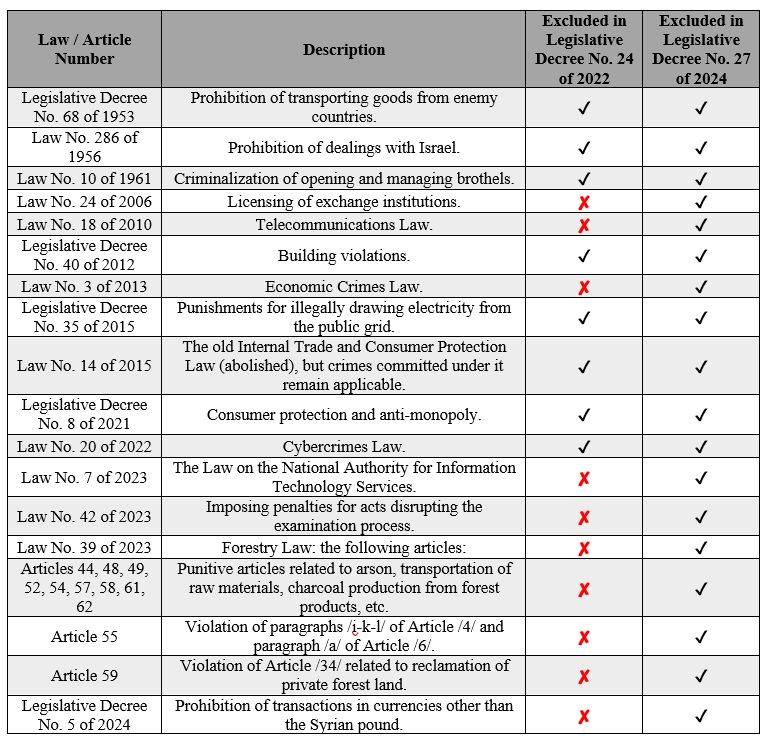

The following table provides examples of companies associated with senior-ranking officers from the security agencies, the military, and their family members:

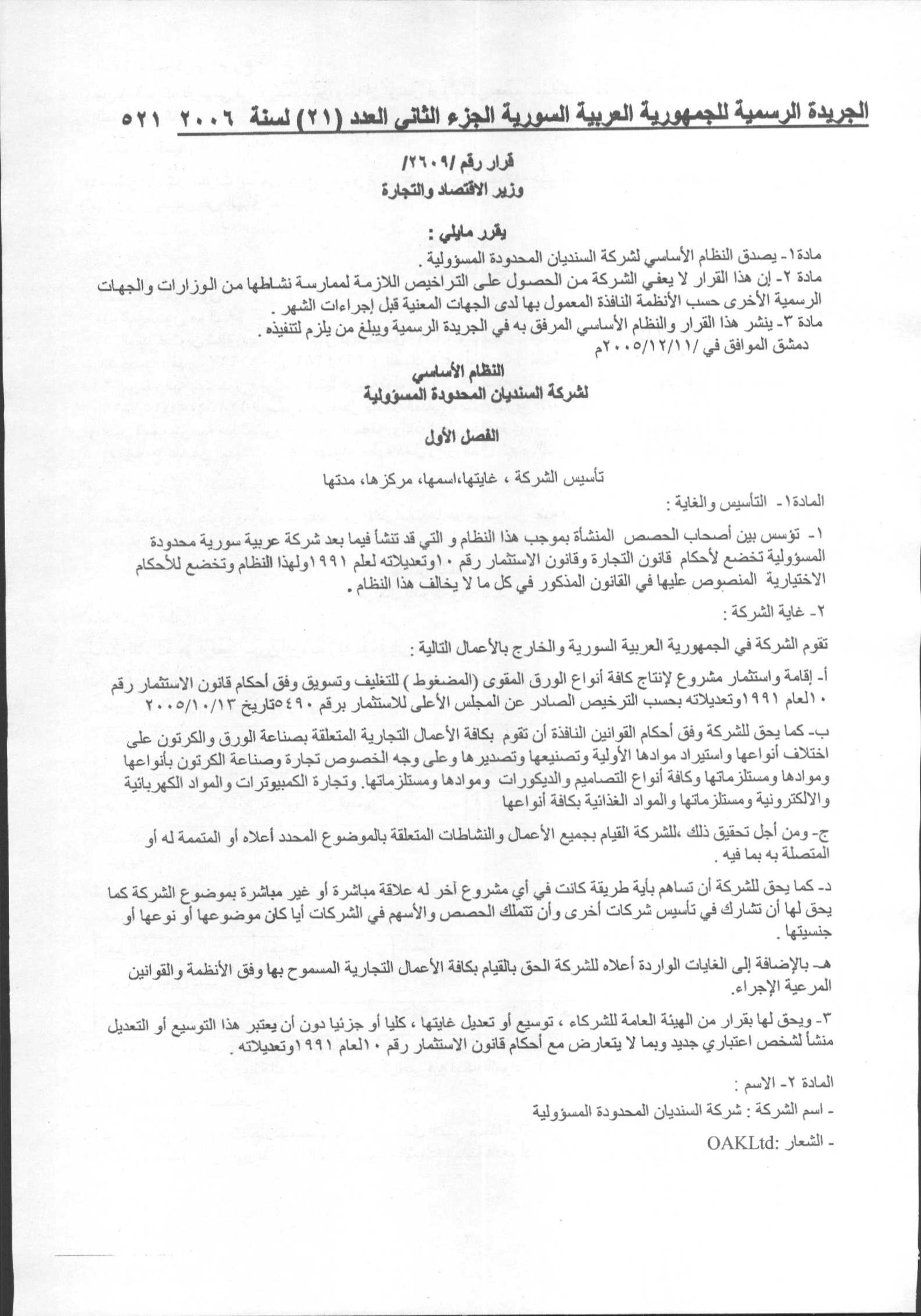

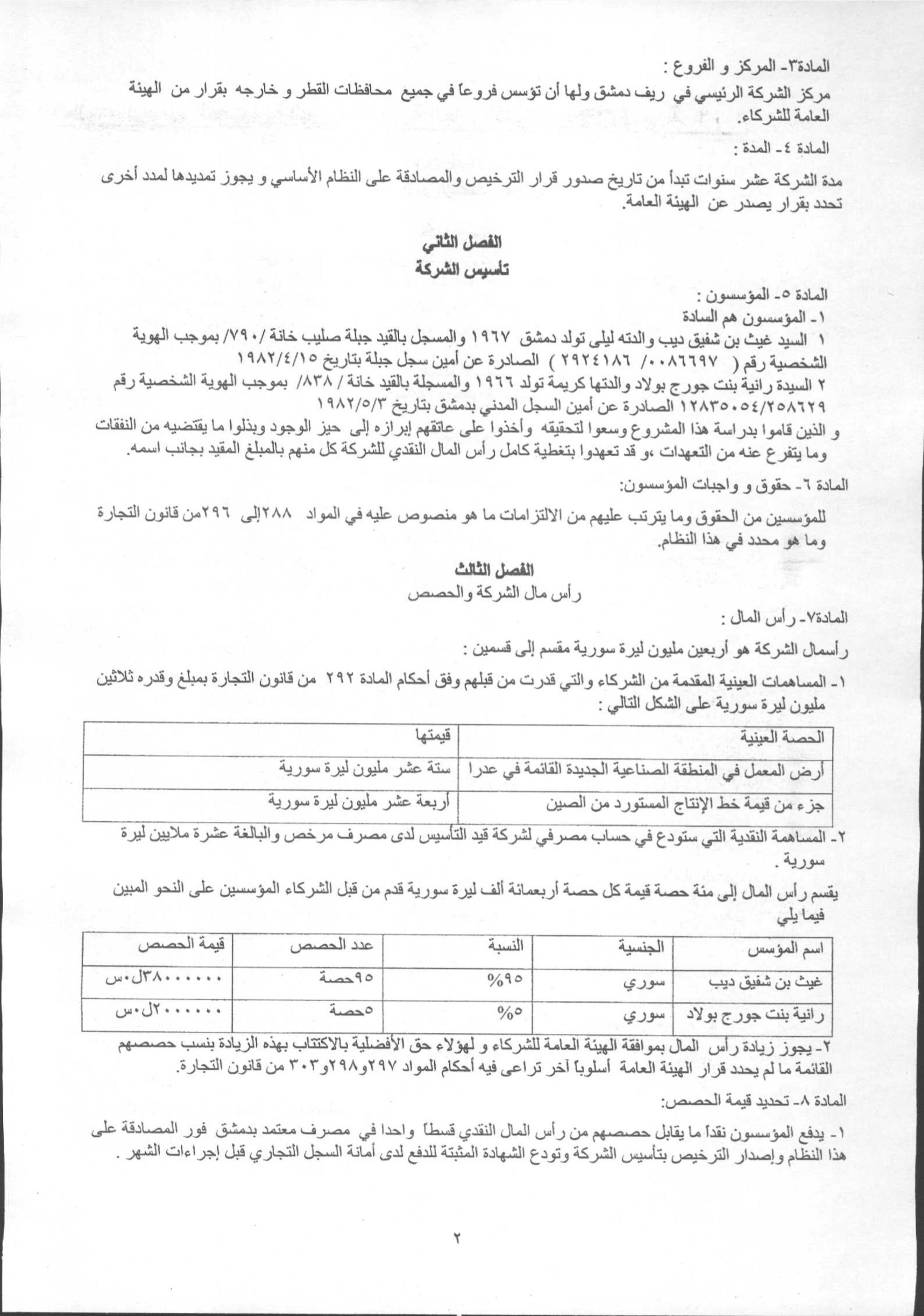

An example of one such company is Sindyan Ltd, owned by Major General Gaith Deeb and his wife, Rania Boulad. Established as a paper manufacturing plant in late 2005, the company’s initial capital exceeded one million USD—at a time when the exchange rate stood at approximately 50 Syrian pounds to the dollar. Notably, Gaith Deeb, who then held the rank of lieutenant colonel, had a monthly salary that did not exceed 200 USD at best.

An official document issued in the Official Gazette – Part II – Issue No. 21 of 2006

([1]) “Syria Orders Freezing of Bank Accounts Linked to Assad Regime” Al Jazeera Net, published on 23/01/2025. Link: https://bit.ly/4hvv9Xg

([2]) The Syria Sanctions Policy Program (SSPP) 2023–2024: An initiative by the Syrian Forum aimed at enhancing the effectiveness of Western sanctions on the Assad regime. Implemented in cooperation with the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks and the Omran Center for Strategic Studies. Link: https://bit.ly/42pam3o

([3]) “Legislative Decree No. 18 of 2003 – Military Service Law”, Syrian Parliament, published on 21/04/2003. Link: https://bit.ly/3GyL0Cq

([4]) “Fraud and Financial Extortion of Families of Detainees and the Forcibly Disappeared” , Association of Detainees and the Missing in Sednaya Prison (ADMSP), published on 16/11/2021. Link: https://bit.ly/40NGufH

([5]) “Shamcoders LLC,” Official Gazette, Issue No. 24, Part 2, dated 22 June 2023. Syria Report. Link: https://bit.ly/3PS8317

([6]) “UN Procurement Contracts in Syria: A Network of Corruption?” Observatory of Political and Economic Networks and the Syrian Legal Development Program, published in November 2022. Link: https://bit.ly/4hroi0Q

([7]) Diana Rahima, “How the Syrian Regime Pressures the UN to Hire Relatives of Its Officials”,Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, published on 10/03/2023. Link: https://bit.ly/4hxclXO

([9]) “A Syrian Craft: Assad’s Regime Uses Shell Companies to Evade Sanctions”, Syria TV, published on 22/03/2022. Link: https://bit.ly/3CnF0zA

President Trump’s Sanctions Rollback Signals Major Shift in Syria Policy

President Trump's decision to lift sanctions on Syria is a historic development with potentially far reaching impact on Syria and the broader region. Syria has been under multiple tiers of sanctions going back to its 1979 designation as a State Sponsor of Terrorism. Additional sanctions were levied because of its occupation of Lebanon and former President Bashar al-Assad's human rights violations against the Syrian people. The announcement, if implemented fully, would see the lifting of restrictions on financial transactions with the Syrian Central Bank and other financial institutions doing business with or in Syria. This could significantly impact the ability to attract and facilitate foreign direct investment, a requirement for any meaningful reconstruction projects. With hundreds of thousands of destroyed or damaged housing units and a debilitated essential services infrastructure, the infusion of foreign capital to fund the reconstruction effort is desperately needed.

Syria's economy, which was mainly driven by agricultural and light manufacturing production, in addition to oil production prior to the war, is ripe for investment and has the potential to begin contributing to the regional economy in quick order. Syria's labor market will likely get a boost from sanctions relief as domestic and foreign reconstruction projects commence. Before this happens, U.S. agencies and regulatory bodies will need to move expeditiously to implement the President's decision. Certain sanctions and designations of Assad-affiliated entities and figures are expected to remain to ensure that they are not allowed to benefit or to escape accountability. In addition, Congressional support will be needed, especially in regards to suspending, and eventually ending sanctions under the Caesars Civilians Protection Act which placed secondary sanctions on entities or countries that conducted commercial activities with the Syrian state.

Wa'el Alzayat

Aggregating Power: The Territorial Orders of Syria

Executive Summary

In the wake of the Assad Regime’s collapse on the 8th of December 2024, Syria stands at a critical crossroads, as it presents both opportunities for reform and risks of further fragmentation. Previously, management of the territorial system of Syria was heterogenous despite the State’s hegemonic outlook. The central state applied diverse formulas for managing the territory focused mainly on building loyalty to the Baath regime rather than focusing on the efficiency and effectiveness of administration to serve local communities. During the upheaval of the Syrian revolution and the ensuing conflict, authorities in Damascus transformed the territorial system in Syria. Many of the areas that fell outside the control of the central regime adopted their own territorial orders. Today, amid the uncertainty surrounding the country's future, there is an urgent need to revisit and understand the territorial structures of Syria—examining their historical trajectories and evolving geography leading up to November 2024. This understanding is crucial for guiding future efforts in restructuring the territorial order in an effective manner; this will be essential for reorganizing the country’s territorial hierarchies, administrative borders, and political economy in a manner that supports sustainable reconstruction and fair representation of Syria’s diverse communities.

As such, this paper proposes an analytical framework to approach the complex spatial dynamics of Syria's territorial orders, examining how they were shaped by historical legacies, centralization efforts, and the impact of 14 years of conflict, influencing governance practices and everyday life across the country. Aggregation in this context refers to the consolidation and concentration of authority at various levels of territorial administrations within set boundaries, shaping the interactions between central and local authorities. Whereas other papers in this series will focus on governmental and formal and informal political dimensions of territories, this paper will focus on spatial manifestations looking into distribution of administrative units, internal borders, and population densities.

The paper begins with an overview of the historical roots of territorial governance in Syria, summarizing its evolution from Ottoman administrative reforms seeking balanced centralisation, through the strong asymmetries imposed by the French Mandate and into post-independence highly centralized governance models. Most importantly, we discuss how territorial systems were divided in two separate overlapping frameworks that were never reconciled, mainly the territorial units (governorates, districts and sub-districts) and the municipal units (cities, towns, and townships). Dynamically changing administrative divisions were persistently used as mechanisms to consolidate central authority and exert control over diverse and often fragmented territories. Societal and regional divisions were often exacerbated by introducing and reinforcing strong spatial asymmetries, which served as tools for managing or manipulating local populations and resources in return.

The paper places a critical focus on the Decree 107 of 2011 as the existing legal framework for managing the local governance. This law will be the point of departure to reform the system of territorial governance in Syria. Understanding how the law was implemented to demarcate the local administration units will be critical for any reform process in the future. The said decree aimed to promote decentralization by granting greater autonomy to Local Administrative Units (LAUs). In theory, it offered a pathway to increased local agency in managing local affairs, transparency, and civic participation. However, in practice, central control remained entrenched, as the central government retained the power to dissolve councils, manipulate their formation, and reconfigure territorial boundaries to serve its political interests. This led to imbalances and disparities in the distribution of councils, limiting genuine local autonomy and fostering dependency on central authority as the ultimate arbiter in local affairs. Rather than achieving meaningful decentralization, the implementation of Decree 107 often reinforced existing hierarchies and patronage networks, undermining the law's intended reforms.

Conflict further fragmented Syria’s territorial governance, giving rise to distinct models of local governance under various de facto authorities. Each governance model tried to adapt to unique political, social, and regional considerations, resulting in disparate approaches to administration, resource allocation, and public service provision. Today, despite the fall of the Assad regime, the legacy of fragmented spatial geometries highlight the challenges of reunifying the territory, adjusting regional disparities and achieving a viable cohesive governance model. In this context, Decree 107 serves as the starting point in understanding the territorial framework and setting a baseline for comparison between the divided areas, as a first step in developing a new unified framework.

By interrogating the spatial dynamics of territorial orders, this paper illuminates the dual role of territorial governance structures as instruments of control and as reflections of socio-political realities. The study underscores the importance of re-designing territorial orders using new spatial demarcations that could balance political authority, administrative efficiency, and local identity. Such designs must prioritize inclusivity, equitable service delivery, and meaningful local autonomy to foster stability, cohesion, and sustainable development. Ultimately, the success of territorial governance in Syria will depend on its ability to adapt to shifting socio-political realities while addressing historical asymmetries, finding commonalities in the various territorial models and harmonizing differences to promote a more equitable distribution of power and resources. We conclude with a series of recommendations for the future of territorial orders in Syria:

- Tackling Systemic and Historical Imbalances: Addressing entrenched disparities to ensure equitable distribution of resources, authority, and representation across all regions.

- Leveraging Cities as Localized Cross-Geography Constants: Utilizing urban centres as anchors of stability and development, fostering connectivity and cohesion across fragmented territories.

- Balancing Peripheral Orders: Harmonizing the relationships between central and local authorities to promote inclusivity, efficiency, and local empowerment in governance.

For More: https://bit.ly/3DgYrue

Governance Challenges in the Upcoming Phase: General Concepts

Introduction

There is no doubt that the success of the Military Command in overthrowing the Assad regime depended on several factors, not least of which were military preparation and training. However, there are other essential and objective factors that were no less significant, even if they were not directly apparent. One such factor is the decline and collapse of public services and governance in regime-controlled areas, alongside the widespread corruption. In contrast, the general conditions in areas under the control of the Salvation Government demonstrated an ability to deliver services and achieve swift justice in a manner consistent with local societal values, providing these areas with a competitive advantage.

The relative success of the Salvation Government in governance before the fall of the regime can be attributed to the following factors:

- Discipline and the Moral Code of Personnel: This factor may seem weak within traditional governance literature, but it played a crucial role during the siege and war endured by the region. A cohesive Moral Code helped maintain order and limit chaos.

- Reducing Governance Layers: By exercising direct authority with the population. This required providing citizens with close access to decision-making centers without passing through multiple administrative layers, particularly in judicial matters.

- Government Focus on Regulation: while leaving service provision to non-governmental organizations and the private sector. This approach saved essential resources for the government and allowed their allocation to developmental purposes, even under conditions of war and siege. It is worth noting that many fundamental governance functions, such as statistical tools and planning, remained suspended as they were considered secondary priorities.

- A High Degree of Alignment with Local Cultural and Religious Values: The government’s value framework and the religious and ethical references of the population were in close alignment; this enhanced the government’s ability to manage societal disputes and balancing varying interests through coordination with existing community leaders and local societal structures.

- Monetary Control of a Small Economy: the control of economy in a contained geographical area was relatively easy and manageable; it allowed for direct supervision and regulation of money flow, and helped curb inflation to some extent.

As a result, essential and critical expertise was accumulated, which may prove beneficial in various areas of state management in the future. However, these experiences cannot be directly transferred when expanding the governance framework from Idlib to the rest of Syrian territory without reconsidering several fundamental factors and adjusting assumptions.

Key Challenges in Expanding Government Operations

The government will face immediate, medium-term, and long-term challenges in the upcoming phase, which cannot be addressed by merely extrapolating the Idlib experience to the rest of the country. Instead, there is a need to delve deeply into the structural reasons behind Idlib’s success rather than focusing solely on its technical modalities, due to the following reasons:

- The moral code, self-regulation, and cohesion that characterized the governance bodies in Idlib will not be available in governance structures plagued by neglect, corruption, and nepotism. Furthermore, the competent individuals within these structures will still require indirect monitoring mechanisms, which cannot be provided by the direct oversight methods that the Salvation Government traditionally relied on to combat corruption. Syria’s administrative structure will require approximately 2,000 senior national level managers and around 10,000 mid-level managers. The central authority, represented by the current Interim Government (comprised mainly of personnel from the Salvation Government), will not be able to monitor them directly. The new government will face significant challenges in selecting, training, monitoring, and holding personnel accountable through intermediary oversight mechanisms. These oversight systems, such as the Central Commission for Control and Inspection and the Central Financial Control Authority during the previous regime, were among the core pillars of corruption. Each time an intermediary governance level is introduced to combat corruption, it must itself be monitored; otherwise, it risks becoming part of the corruption system.

- There is no doubt that the traditional structure of local administration in Syria requires a comprehensive reassessment of its levels, size, and administrative divisions. In Idlib, the Salvation Government abolished the governorate level in administration, opting instead to manage major municipalities (each roughly the size of a subdistrict). This approach cannot be replicated in other governorates, and efforts must be made to unify local administrative levels to ensure consistency. The government, operating from Damascus, will not be able to exert centralized control, nor will it be feasible to consolidate smaller municipalities into larger ones across all governorates at once, particularly given the legacies of the conflict and the divisions left by years of strife among local communities. At the same time, the country cannot be managed in an asymmetrical manner.

- Non-governmental organizations have been able to provide essential and high-cost services, such as healthcare and certain educational services, through resources provided by Syrian expat communities abroad and international donors. However, it will not be possible to significantly expand these resources. Until the central government can sustainably provide these resources to local communities, a critical challenge will lie in the fair and transparent distribution of incoming resources to Syria. The provision of services will significantly determine the new government’s acceptability in the not-so-distant future. The government will need approximately $10 billion annually to restore basic infrastructure and provide services at an acceptable level. Donor funding of this scale will not be available, and the initial contributions made by Qatar and Turkey will not suffice to meet these needs in the long term.

- Balancing societal interest will pose a significant challenge in areas where cultural and ethical values do not align with the government's moral foundations. Syrian communities cannot be governed solely on the basis of overt religious and ethnic allegiances, as each group has its own contradictory social levers and customs representing competing interests and clashing local leadership and patronage networks (many of which transcend specific ethno-sectarian groups). Agreements with certain community leaders will not guarantee the satisfaction of other leaders. Thinking in terms of ethno-sectarian groups will place the new government in unfamiliar dilemmas, unlike those faced in Idlib, where religious and cultural groups were relatively limited in geographic and spatial terms. Disputes and competition within local communities will consume the administration’s time and cause stresses unless sufficient space is allocated for local communities to engage in dialogue and negotiate the representation of their diverse and conflicting voices in the future.

- The recovery of the Syrian economy will; be another key issue. Syria’s economy is diverse and complex; it cannot be managed using the inflation control tools applied in Idlib. There will be significant demand for consumer goods in the upcoming phase, with the commercial and industrial sectors competing to meet these needs (the former advocating for lifting customs restrictions, while the latter initially seeking protectionist measures). This competition will, in turn, generate demand for various financial operations, which the government must balance through centralized regulatory mechanisms. Even if financial transactions were managed by the private sector within a free market system, foreign exchange management and national balancing of the accounts will be necessary to control inflation. Currently, the sharp demand for the Syrian pound, driven by the return of refugees and expatriates, has supported the stability of the currency. However, once reconstruction and investment activities begin, the volume of financial resources in the markets will cause rapid flow of cash into the markets and will induce significant inflation (though foreign exchange rates may remain stable). While this growth will eventually create job opportunities and enable Syrian families to regain their economic capacities, the benefits of this economic growth will spread slowly compared to the anticipated rise in inflation. This means that approximately 60% of the population will face the risk of food insecurity in the short to medium term. A rapid safety net must be established to prevent public dissatisfaction with the current government from escalating into widespread discontent within a few weeks.

- Reconstruction will require resources that are currently unavailable and unlikely to be secured through donor contributions, particularly in light of ongoing sanctions (with over-compliance with sanctions, extending far beyond their literal terms). GDP estimates have dropped from $58 billion in 2011 to around $20–22 billion today (considering that part of today’s GDP is linked to the war economy, non-militarized economy may actually not exceed $18 billion). The current economy is highly contracted, and investments in reconstruction will create significant opportunities for accelerated growth as well as risks of growth happening at the expense of vulnerable groups, as noted above. To recover the lost GDP, Syria will require annual growth of approximately 6–7%, which is achievable initially in a contracted economy that suddenly opens up to new investments (albeit with the accompanying risks of inflation). However, this growth rate will taper off over time and cannot be sustained beyond 4–5% in subsequent years, even under the best circumstances. Consequently, recovering lost GDP will not likely be achievable before 2040, even with open investment markets.

The losses to the Syrian economy can be divided into three components:

- Direct material losses: Estimated at around $125–150 billion, representing the value of destroyed assets, including housing, services, infrastructure, factories, and more.

- Indirect economic losses: Estimated at approximately $200–300 billion, representing the loss of production that could not be realized due to direct material losses.

- Lost opportunity costs: Estimated at roughly $400 billion, representing the value of potential growth that could have been achieved if the revenues lost to economic damage had been reinvested in the Syrian economy.

At best, the Syrian economy could recover the first two components within 15–20 years. However, this projection requires a delicate balance between demands for growth with social protection needs. Tax rates must be calculated with precision to encourage investment on one hand, while also ensuring the provision of public services to safeguard social welfare and support pro-poor growth on the other. The new government's announcement of a free market and minimal taxation would reassure investors, but it risks sparking a hunger uprising if socially and legally acceptable frameworks for social solidarity and guarantees for protecting the most vulnerable groups are not set up soon.

Balancing Stability and Legitimacy

The Salvation Government acquired the de-facto legitimacy to manage the Interim Government under what is referred to in constitutional literature as revolutionary legitimacy. This form of legitimacy allows it to lead the transitional phase under the banner of maintaining stability. However, legitimacy has another dimension—legality or de jure legitimacy—derived from the coherence of the governance system, starting with the constitution, followed by laws, and ending with implementation and community participation. Without the de facto legitimacy, the de-jure one will not likely be established, and without de-jure legitimacy, the de-facto one will not endure politically and will become meaningless.

There are fundamental issues that must be addressed to provide mechanisms for building de jure legitimacy in line with the structural challenges the new government will face in the coming phase. These include:

- Establishing constitutional legitimacy and national dialogue: This should be conducted within a participatory and inclusive framework. Although this process may take time to mature, it must begin swiftly.

- Economic recovery and restoration of services: This is the most significant challenge and includes ensuring salaries and wages not only for public sector employees. Raising public sector salaries alone will create inflation in other sectors that cannot be contained in the short term.

- Reforms to the local administration system and the organization of local councils' operations: Governance systems have developed differently across various areas, even within regime-controlled zones, where each region was managed according to distinct local parameterss despite the existence of a unified legal text in the form of Decree 107 of 2011.

- Organizing Civil Society Operations: Establishing practical partnerships with non-governmental organizations to provide a social safety net is crucial. This does not mean limiting civil organizations to relief work. While relief efforts are urgently needed in the short term, such work does not generate economic multipliers or create job opportunities. It is essential not to rely entirely on relief efforts. Civil society organizations are a fundamental part of creating a positive environment for the return of investment in Syria and should not be restricted solely to charitable activities.

- Reconstruction of Cities and Towns: Many cities and towns will require rapid preparation to regulate construction activities, ensure public safety, protect public property, and provide infrastructure. The Syrian planning system is not equipped to quickly address these challenges, particularly as, in recent years, it has shifted its focus toward real estate development projects while neglecting the right to housing for displaced populations.

- Community Reconciliation: Transparent and localized mechanisms are essential for addressing issues of social peace. These mechanisms must engage with existing community structures in all their diversity and avoid reducing them to a single type of sectarian leadership.

Subsequent papers will be issued to outline these mechanisms in detail and foster dialogue around their activation.

Tribe and Power in Syria: History and Revolution

Introduction

The history of Syrian geography is inseparable from the history of its tribes, which settled in the Levant and its Baadiyah (deserts and steppes) during ancient pre-Christian times. As the geography changed, so did ruling regimes,; tribes also experienced significant political and structural transformations, forming a historically extended social system with evolving features still observable today.

An examination of Syria's political history, both ancient and modern, reveals that tribes and tribalism are both key factors in social, political, and power dynamics; often embodying power itself. Arab and other tribes established kingdoms, emirates, and states, ruling regions across different historical periods. They engaged in conflicts, alliances, and submission with various authorities, possessing elements that made them a governance system predating many ancient and modern structures. Through these interactions, their social structures evolved, transitioning from nomadic to semi-settled, with the latter eventually merging into cities and becoming fully urbanized. The latter shift is harder to trace compared to the more distinct nomadic structures.

With Syria's integration into the modern state system, pivotal transformations occurred within tribal and clan structures due to various successive changes (economic, political, social, military, legal). These cumulative effects were evident in the tribes and clans, starting with their economic patterns, which were dismantled as they were either willingly or forcibly moved from a nomadic to a settled, agricultural-based economy. This shift led to a change in their historical roles, most of which were lost to the nation-state, which confined them within new borders, stripping them of the open geography that had historically been a key source of their strength.

The tribe adapted to the modern state structure embracing the new dynamics. Depending on the shifting powers, the role and position of tribes and clans evolved: sometimes as a disruptive or competing alternative; and at other times as a strong ally with considerable influence in rural areas, counterbalancing urban families and notable figures. In many cases, tribes served as a broad social basis, forming much of Syria's rural landscape, which, in turn, acts as a crucial social and economic backbone, a field for mobilization, and an experimental ground for political elites and ideological parties. Through these changes, the structure and roles within tribes shifted, affecting the nature of "tribal leadership" embodied by sheikhs and princes—both in their political roles and their ties to the social fabric. This fabric gradually transformed into more stable rural structures with diverse economic patterns, fostering a new social sphere where the “sheikh” no longer held sole authority.

Traditional nomadism gradually declined, with tribes settling geographically and adopting regional identities. Local sheikhdoms and tribal notables emerged, while tribe members engaged in agriculture, trade, and state jobs; altering settlement patterns, and weakening traditional tribal cohesion. This shift moved the tribe/clan concept from a political-organizational role to a socio-cultural one, reshaping social relations and levels of solidarity, now influenced by geographic, economic, developmental, and political factors.

Within Syria's diverse tribal landscape, the northern tribes are particularly notable for their influence, extensive geographic reach, and border-specific dynamics, with cross-ethnic and cross-sectarian structures. Many quickly engaged with these elements when the Syrian revolution began in 2011, followed by military, security, and economic repercussions. The state's withdrawal from most regions subsequently tested the tribes' ability to assume roles in local governance.

During these phases, tribes emerged as a significant social force, reacting to events with diverse political stances, reflecting cumulative impacts on their structures. Initially, when peaceful protests started tribal groups mobilized independently of traditional authorities (sheiks, princes, notables) and then shifted towards militarization marked by overlapping regional tribal interactions. As the Assad regime waged open war on the social fabric of the revolting areas; distinct zones of influence emerged, divided among local, regional, and international actors. This fragmented tribal geography turned tribes into key, cross-regional social structures, and a field of competition.

Unlike the peaceful phase, militarization intensified tribal representation at all levels, creating vertical and horizontal divisions within tribal structures and reviving tribal leadership as a local player with political, military, and social roles. Tribes, heavily engaged in Syria’s events, were also among the most impacted by military, security, and economic fallout, especially through forced displacement—unprecedented in modern Syrian history. After 2016, as the regime and its allies reclaimed opposition areas, military actions receded northward to Aleppo and Idlib, which became hubs for successive waves of internal displacement, both within these governorates and from other parts of Syria.

In this complex context, within the north-west opposition enclaves after 2016, a new organizational trend emerged: the establishment of “tribal councils”. Most tribes established their own councils, functioning as administrative bodies with diverse responsibilities, thereby reducing reliance on the sheikh’s traditional leadership. This shift promoted tribal presence in a new organized form, partially reviving the tribal spirit and roles. Notably, the initiative extended beyond Arab tribes to Kurdish and Turkmen clans. However, the councils' roles remain limited, and their impact on the tribal structure and traditional leadership remains ambiguous, as this move is unprecedented in Syria’s tribal landscape.

Thus, the post-2011 period marks a pivotal phase in Syrian state history and its social structures. Examining tribes over twelve years of conflict reveals interactions of prominent local social structures during a critical period. This study enhances a body of longstanding research, as tribes have long shaped the region’s intellectual heritage, particularly in Syria Occupying a significant place in sociological, anthropological, and political studies. Tribes often serve as interpretive tools for major political events or as frameworks for understanding local conflict dynamics. However, this study diverges from such an approach. It does not view tribalism as a lens for the Syrian conflict nor explores tribal influence on it; rather, it examines the conflict's impact on tribes and their varied responses across its phases, consequences, and actors.

This study first seeks to explore the history of tribes and clans within Syrian geography, especially in the north-west. Examining their historical relationships with various successive authorities, structural shifts, and the changes that shaped their current forms. It proceeds to map the tribal structures across Aleppo and Idlib, identifying their current geographic and demographic distribution. The study also analyzes their diverse roles and interactions (political, military, social) after 2011, emphasizing key impacts, particularly the complex effects of forced displacement. Lastly, it explores the emergence of "tribal and clan councils" as a new organizational phenomenon within Syria’s tribal framework post-2016, defining their roles, influence on traditional tribal governance, and effectiveness within the social structure.

In line with these objectives, the study/book is methodologically and analytically structured into three chapters. Chapter One serves as an introduction and review of the history of tribes and clans within Syrian geography generally, with a focus on Aleppo and Idlib. It examines their historical relations with successive authorities, structural transformations, and various shifts leading to their current forms. This chapter adopts a systematic historical periodization across seven key phases: an overview of the region’s ancient history and tribes, the Ottoman era, the Arab government under King Faisal, the French colonial period, the era of national independence, the union with Egypt, and the Ba'ath periods—first under the early Ba'ath regime, then under Hafez al-Assad, followed by the first decade of Bashar al-Assad's rule.

Within this broad historical scope, the study identifies several key variables to track and assess across each era and phase, including: active tribes in the north, the nature of their relationship with central authority and the factors shaping it, evolving roles of tribes and clans, tribal conflicts and interrelations, structural shifts—economic, social, political, and legal—and their impacts, major tribal migrations and displacements within the region, factors driving urbanization and settlement, and shifts in the concept of tribal leadership.

Chapter Two picks up where the first left off, examining tribal and clan interactions with the Syrian revolution post-2011 through its various phases, actors, repercussions, and impacts. This chapter is divided into four sections. The first section explores the demographic, economic, and cultural conditions of tribal areas in Aleppo and Idlib on the eve of the revolution, mapping the presence of twenty-five tribes encompassing 220 clans, alongside twenty-seven independent clans of diverse ethnicities (Arab, Kurdish, Turkmen, Circassian, Gypsy). A field survey identifies approximately 2,033 geographic points where these tribes and clans are concentrated across administrative units (cities, towns, villages, neighborhoods, and key farms).

Following this mapping, the section delves into the motivations and forms of tribal and clan participation in the early stages of the 2011 uprising. It then moves to the phase of militarization, analyzing tribal armed groups in Aleppo and Idlib. The study documents over twenty-three tribal military groups allied with the Assad regime and more than thirty-eight groups aligned with the opposition between 2012 and 2020, as well as the influence of jihadist organizations and their relationships with local tribes. The section concludes by examining the non-military roles tribes and clans played during the conflict, particularly their adaptation to local governance as state authority receded, leaving administrative functions vacant in these areas.

The second section of Chapter Two examines the forced displacement experienced by tribal structures in Aleppo and Idlib and its complex effects. It includes a survey of displaced areas, an analysis of the displacement context, and the parties involved, as well as documentation of major clans displaced from other Syrian governorates to Aleppo and Idlib. This section provides a detailed map of forced displacement phases in Aleppo and Idlib from 2012 to 2020, covering approximately 1,233 geographic points (cities, towns, villages, key farms) affected by varying degrees of forced displacement, along with thirty neighborhoods in Aleppo. It examines the political and military context of displacement, the actors involved, and the compounded impacts on tribes. Additionally, it includes a survey of areas where partial return has occurred, covering approximately 556 geographic points, while 707 locations remain uninhabited as of early 2023.

The third section examines the nature and extent of tribal military participation within major military formations in northern Syria up to early 2023, across various zones of control. It maps out key formations and tracks the impact of displacement on factional structures in Aleppo and Idlib, especially following the arrival of dozens of displaced factions from other Syrian regions.

The fourth section is dedicated to analyzing the emergence of "tribal and clan councils" in the north after 2016, exploring the motivations, dynamics, and contexts behind their formation. This includes a survey of around thirty tribal councils and over 130 clan councils in Aleppo and Idlib. The study then focuses specifically on the effectiveness of seventeen prominent tribal councils, assessing them first from the perspectives of council members and then from the viewpoint of tribal and clan members in the region, to gauge the scope and future of these councils and their varied impacts. Additionally, the section examines the parallel formation of "family and notable councils" in certain cities of Idlib as a counterpart to "tribal and clan councils" in the rural areas of Aleppo and Idlib.

Chapter Three presents the results of the field survey conducted by the research team, mapping the diverse ethnic composition (Arab, Kurdish, Turkmen, Circassian, Gypsy) of tribes and clans in Aleppo and Idlib. It includes fifty-two graphical maps and fifty-two statistical tables detailing each tribe, the number of associated clans in the two governorates, key family groups, and the geographic areas they inhabit, categorized according to the official administrative divisions in Aleppo and Idlib (city, town, village, neighborhood, key farms).

The study/book bases its chapters and sections on a diverse range of primary and secondary data sources. In addition to books, academic studies, historical references, documents, and archives on the region and its tribes, it relies heavily on field data as primary sources. Various research tools and methods were employed for data collection, primarily interviews and field focus sessions conducted between 2021 and 2024. These sessions involved over 780 sources from diverse groups, including tribal sheikhs, princes, and notables; aghas and dignitaries; founders and members of tribal councils; genealogists and tribal experts; social and political activists; local council members from tribes in the region; defected officers and tribal field commanders; specialists and researchers focused on regional or tribal issues; and numerous displaced individuals who participated in focus sessions on forced displacement, among others.

Key Findings and Conclusions

Based on the chapter summaries, with Chapter Two marking the start of the study’s practical findings, this paper provides a condensed overview of the study’s core findings. Key insights include: the structure, influence, and geographic distribution of tribal and clan networks in Aleppo and Idlib; their interactions with the Syrian revolution; and their varied roles in political, military, and local governance spheres. The study also examines the diverse impacts of the conflict on these structures, particularly forced displacement, and explores the emergence of tribal councils, analyzing their current and future implications. Lastly, it examines the position of tribal structures within the power dynamics and the complex relationship with authority, especially regarding the management of loyalties and the form of the state.

For More: https://bit.ly/4gO3oZG

Syria at a Crossroads: Between Hope and Uncertainty

Introduction

An armed alliance of the Haya’t Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and the mainstream Syrian opposition forces have launched a new military operation against the Assad regime and Iranian-backed militias in Western Aleppo, dubbed the “Deterrence of Aggression.” This marks the first large-scale ground offensive in Northern Syria since March 2020. (1)

Although the stated objective of the operation was to counter further escalation by the regime and Russia, following intensified airstrikes and bombardment on Northern Syria, the poor performance of regime forces allowed the HTS and the opposition to achieve significant and unexpected advances. By the end of Thursday December 5th, Syria’s opposition forces had regained control of the Aleppo province, eight years after being forced to withdraw from the city in 2016 due to the strong support provided to the Assad regime by Iranian-backed militias and Russia. Alongside the capture of Aleppo, the armed alliance has taken control of the southern countryside of Idlib and the city of Hama, where the regime had reorganized its groups and brought reinforcement to stop the collapse of its defense lines, yet to no avail.

This article gives insight into the operation's background and how Syria’s conflict reignited, the current situation on the ground explaining the reasons of the fast advancement, the military institution building of the HTS and the Syrian National Army (SNA), and the armed alliance and what does it tell the world. Lastly, it addresses the potential scenarios awaiting Syria and highlights the relevant policy implications.

The Road to the Operation

Syria is back under international spotlight and likely to remain so. Many analysists have warned that the “frozen” Syrian conflict might blow up at any moment. This article (2) explained the significant changes that were unfolding within each zone of influence, alongside the escalating violence across the country, and argued that the increasing fragility and uncertainty in Syria indicated that the status quo was unsustainable. Nevertheless, Syria has attracted far too little attention from the international community, in which the worsening humanitarian crisis was largely overlooked and less than 30% of the required funding in 2024 was provided for the humanitarian response(3).

The ‘frozen’ conflict in Syria has never been frozen. Neither the regime nor its allies have stopped the bombardment and shelling against Northern Syria, nor the HTS and opposition armed groups have ceased to launch 'raids' against the regime forces in response. Since March 2020, Northern Syria has been on the brink of open war multiple times, the most astonishing incident was the drone attack on the military academy of Homs, which killed over 100 regime soldiers, followed by a massive Russian escalation against Northern Syria(4).

Making Sense of the Shocking Operation

A few months ago, the rebel forces signaled their intentions to launch an operation toward Aleppo, releasing a video that quickly went viral within local communities. On the ground, Russia and the regime have intensified their bombardment against the local population and infrastructure in Northwestern Syria, leading to the displacement of thousands of civilians. Consequently, the sense of safety was lost due to the continuous bombardment of the regime and Russia, and the resentment and grievances among locals, particularly IDPs living in makeshift camps, was reinforced. UNHCR estimates the numbers of the internally displaced persons in Northwestern Syria to be close to 3.6 million out of 5 million, 1.9 million of whom have been living in camps and self-settled sites (5). For years, many displaced young men, and even elderly men, have been balancing work with intermittent military training. This reality illustrates why the HTS and the armed opposition set the objective of the operation as facilitating the return of displaced people to their original cities and towns(6).

The objective of the operation was set to be limited, yet the collapse of the regime’s defenses has allowed the armed alliance to advance unexpectedly fast, shocking Syrians as well as the experts who have been analyzing the Syrian conflict for more than a decade. While the institution-building efforts of the armed groups have had a considerable impact, the severe blows dealt to Hezbollah and other Iranian-backed militias by Israel since mid-September have been a decisive factor in the collapse of the regime forces on strategic fronts. Moreover, Moscow’s diverted attention in Ukraine, including the partial withdrawal of warplanes and air defense systems to reinforce its forces there, has left the regime without the robust aerial cover it previously relied on.

Other reasons also explain the impressive success achieved by the ‘Deterrence of Aggression’ campaign. For instance, many armed groups have extensive combat experience across various regions in Syria, including Aleppo and Hama, giving them a deep familiarity with the geography. This experience is further complemented by their history of numerous assaults on regime bases, as well as their involvement in laying sieges. Additionally, sleeper cells played a critical role in supporting the oppositions’ advance, providing intelligence and logistical aid during the operation. Also, the use of drones proved to be a game-changer, giving the opposition a significant advantage by enabling precise strikes on regime troops, tanks, aircraft, helicopters, bases, and even high-ranking commanders.

The operation has been carefully planned and executed on multiple levels. Armed groups have applied lessons learned from the numerous operation rooms established throughout the Syrian conflict. The planning demonstrates high tactical and operational coordination, a structured communication strategy, and a focus on service provision. This suggests significant preparation and an evolving institutional capacity.

Institution Building of the Armed Groups

Despite the Russian and regime bombardment, the relative calm since March 2020 has allowed the armed groups to reorganize and achieve a certain level of institutionalization. Much of the focus has been on the development of the HTS-backed Syrian Salvation Government (7)in Idlib and to a less extent the military capacity-building efforts of HTS. In contrast, the institutional growth and capacity-building efforts of the Syrian National Army have received far less attention. The clandestine nature of the military institutions and the suspicion that much of the online materials might be mere propaganda had contributed to keeping them under the radar. Nevertheless, the reality on the ground appeared to indicate considerable changes(8), yet it was impossible to assess the extent and influence of these changes on the battlefield.

HTS has been transforming itself into a hybrid actor by modifying insurgent tactics and claiming conventional army principles simultaneously. First, HTS has transformed its insurgent tactics, most importantly, developing its drone capabilities, which seem indispensable for the current battle. Before the current use of drones, HTS’s drone attacks have reportedly reached the Russian Khmeimim Air Base in Latakia(9) and the regime's stronghold al-Qardaha (10)

among dozens of other locations in 2023.

Second, HTS began adopting functions traditionally reserved for conventional armies, including the establishment of a military academy, a military training department, a conscription office, and a center for military studies and planning. The group has benefited from former Syrian military commanders who defected from the regime during the war; their expertise was invaluable for HTS in restructuring its armed wing and building institutions. The head of HTS, al-Jawlani, even expressed intentions to establish a defense ministry and “get out of the factionalism situation (11)"

Last year, HTS faced a challenging test of the coherence of its armed wing when it purged hundreds of its military officers, including prominent figures such as Abu Maria al-Qahtani, under accusations of espionage. Neither the killing of al-Qahtani nor the defection of another prominent figure, Abu Ahmad Zakkour, have disrupted the group’s chain of command. However, these events triggered a wave of popular protests that posed serious challenge to its local acceptance (12).

The Syrian National Army (SNA) has also been occupied with following up on institution building. Aiming at reorganizing the opposition factions under one command, the Defense Ministry of the Syrian Interim Government established a military academy, initiated a process of reorganizing the economic resources of the factions under a centralized mechanism, allocating significant resources to the military police, and established a central border guard units to counter human and illegal goods trafficking. Moreover, subgroups have been undergoing professional military training, including using drones. In addition, members of the SNA started to receive education on international humanitarian law after singing an action plan with the United Nations to end and prevent the recruitment use and killing and maiming of children. Hasan Alhamada signed the action plan for the SNA, Mohammed Walid Dowara for the Jaysh al-Islam, and Amer al-Sheikh for the Ahrar al-Sham. Al-Sheikh is one of the newly established ‘Administration of Military Operation Room’ leaders (13).

On the other hand, the regime’s institutions were grappling with severe challenges. Anonymous attacks have targeted highly securitized areas in Damascus, its outskirts, Homs, and Quneitra undermining the regime’s control in these regions (14). Additionally, the continuous targeting of regime locations by the IDF has also played a significant role in weakening its forces. The regime’s involvement in the Captagon industry and trafficking has also affected its military structure, occasionally resulting in infighting among various official and auxiliary forces (15).

The armed opposition groups have always perceived the regime to be weak and incapable of fighting a battle without the support of Russia and Iran. A high-ranking commander (military defector) expressed that “the regime is divided vertically between Russia and Iran” and that this has deeply influenced its “military structure”(16). The leader of HTS, al-Jawlani, has always propagated that the regime is weak and defeatable. Moreover, he revealed his intentions to launch an operation on various occasions. In early 2023, for instance, he said that “we are ready for battle at any time, God willing, whether in attack or defense… there will be an attack [on the regime]. We will not wait for the regime to attack us... The decision is made, but we await the appropriate time(17)."

The Armed Alliance: What Do They Tell the World?

There has been misinformation about the armed alliance, and various international media outlets have labelled them as ‘jihadists’. Much of this misinformation stems from two simple facts: First, everyone stopped paying attention to Syria, assuming that everything, including the ideological tendency of armed groups such as HTS, has remained the same. Second, the mainstream opposition armed groups have been largely overlooked because HTS has proved itself to be the dominant actor.

To tackle these points, one should first look at the profiles of the leaders of the newly established ‘Administration of the Military Operations Room’, Jamil al-Saleh, Amer al-Sheikh, and most importantly, Abu Muhammed al-Jawlani. Jamil al-Saleh is the leader of Jayish al-Izza, a former commander (major) in the Syrian Army who defected from the regime in 2012. He established his group in 2012. His motivation to fight against the regime is not merely political but also personal since he lost more than 30 members of his family member in a massacre that claimed the lives of over 70 people in al-Latamna in Hama – which made him principled in fighting against the regime and pragmatic in allying with the hardliner HTS(18). Amer al-Sheikh, the leader of Ahrar al-Sham, is from Damascus countryside. He served as the commander of Ahrar al-Sham in Daraa province before moving to Northern Syria after refusing to reconcile with the regime in 2018. In addition, he is one of the opposition commanders who signed the UN’s action plan to end and prevent the recruitment and use and killing and maiming of children (19).

Lastly, and most controversially, is Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani. A veteran jihadist who once served in al-Qaeda’s ranks in Iraq, al-Jawlani later shifted his approach by purging jihadist elements in Northwestern Syria. Pragmatic in nature, he received support from ISIS to establish al-Nusra Front, the predecessor of HTS, in 2012 before pledging allegiance to al-Qaeda to avoid being ISIS’s branch in Syria and counted on al-Qaeda’s support in his fight against ISIS. In July 2016, he rebranded his group as Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, breaking up ties with al-Qaeda under the external pressure of the airstrikes of the US-led coalition to defeat ISIS and the internal pressure of opposition armed groups. Finally, he established Haya’t Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) as a broader armed coalition in January 2017(20).

Driven by survival and appetite for power, al-Jawlani led HTS’s mission of cracking down on all rivalries, revolutionaries and Jihadists, in which HTS became the dominant force in Idlib with other secondary groups operating under the ‘al-Fateh al-Mubin’ operations room, which HTS leads. While doing so, al-Jawlani modified his narrative, claiming to represent the Syrian revolution and justifying his moves under the pretext of achieving unity and building a model for Syria. In Short, he recognized that the Islamist radical agenda wouldn’t grant his survival, let alone expand HTS’s influence to be a dominant force in Northern Syria.

The group’s transformation warrants attention indeed, but it is essential to consider its history including human rights violations, authoritarian tendencies, and practices that triggered widespread resentment and protests before (21).

Nevertheless, it is also crucial to consider that this transformation has shaped the narrative and behavior of the rebels in this battle thus far. In contrast to the first wave of the conflict in Syria, the revenge narrative is primarily absent. Moreover, Today’s rebels are more politically mature than 2015 – the painful Syrian tragedy seems to have taught them a lesson.

The HTS-backed Salvation Government’s ‘Department of Political Affairs’ has been issuing statements reflecting this political maturity's nature. Notably, the department has issued a statement communicating rebels’ commitment to protect consulates, historical and cultural sites, churches, and different (international) schools and grant the “rights of civilians from all sects and Syrian components” (22). Moreover, they went far as to call on Russia not to associate its interests with the regime, considering Moscow as a “potential partner in building a bright future for free Syria (23)" in another statement – among other statements and speeches. It seems like the rebels have come to realize that war is an extension of politics. The next few weeks will tell whether rebels will stand the test of time and prove that change has taken root.

Peacebuilding: The Mission is Not Impossible

There is no doubt that the regime is responsible for the prolonging of the conflict and the current escalation because it has continued to target civilians in recent years and refrained from engaging in a meaningful political process to open a new chapter for Syria. Assad has not been willing to compromise; he overestimated his ability to stand the test of time with his regime intact, and his strategic patience has been leading Syria into a strategic disaster.

On the other hand, the HTS, a terrorist-designated organization, will remain a debatable issue for policy analysts and policymakers – as it has always been. In 2015, Lina Khatib argued that “instead of putting Nusra [the predecessor of HTS] and the Islamic State in the same basket, the West should look beyond the Nusra Front’s ideological affiliation and encourage its pragmatism (24)." Nine years have passed, and it seems that this policy has contributed to the efforts of countering terrorism, particularly al-Qaeda and ISIS (25). Later, in 2021, Jerome Drevon and Patrick Haenni argued in favor of a conditional engagement with the group on two central matters: “HTS’s human rights track record and a clarification of its long-term vision for a political solution in Syria(26)".

Syria is indeed at a critical crossroads, with the current developments shaping its future. Several scenarios lies ahead: (1) a military victory, either in the short or long term; (2) the escalation of a regional war on Syrian soil if Assad's Iranian or Iraqi allies take a risky gamble by backing Assad militarily, undermining any near-term prospects for peace; (3) another round of a fragile frozen conflict if a ceasefire is reached without political solution; or (4) in the most hopeful scenario, a political transition that prevents further destruction and pave the way for a new chapter for Syria.

Assad must be forced to accept a political solution based on the 2254 resolution. Until then, crippling Assad’s ability to target civilians and displacing them is essential to prevent a humanitarian disaster as well as maintaining the deradicalization tendency among armed groups. In other words, the indiscriminate targeting of civilians, which has been a characteristic of Assad’s way of war, will trigger past traumas and potentially revive the narrative of revenge, causing a never-ending cycle of violence.

HTS must be pressured more to compromise its authoritarian tendency. The most effective way to achieve that is by granting a good and inclusive governance in Aleppo and Hama by supporting the Syrian civil society – the most crucial factor for driving democratic change in the long term. Finally, the international community has failed Syrians multiple times; it should not fail them once again. The historic city of Aleppo, the heart of ancient civilizations, and the city of Hama, which suffered under the regime for decades, should not be left behind.

([1]) Charles Lister, Syria’s conflict is heating up once more, 30 November 2024, https://cutt.us/JXdbA

([2]) Fadil Hanci, Syria Has Adapted to the Gaza War’s Repercussions While its Conflict Dynamics Remain Dominant, in “Regional Impact of the War on Gaza”, https://bit.ly/4cGWKlH

([3]) Syria Arab Republic, Humanitarian Response Plan, https://cutt.us/FNgge

([4]) Briefing on the Events of the Syrian Scene - October 2023, Omran for Strategic Studies, 9 November 2023, https://cutt.us/wQGmi

([5]) North-west Syria, The UN Refugee Agency, https://cutt.us/WK8Zi

([6]) Informal conversations with residents in Northern Aleppo between January-May 2024.

([7]) For on the institutional capacity of the Syrian Salvation Government see: Aaron Y. Zelin, The Patient Efforts Behind Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’s Success in Aleppo, War On The Rocks, 3 December 2024, https://cutt.us/AuSwg