Events

Establishing a National Farmers’ Association (NFA) in Opposition- Held Areas

Introduction

In opposition-held territories, the agricultural sector suffers from a variety of complex challenges. Among those challenges is that supply exceeds demand due to poor planning, absence of refrigerated storage facilities, weak purchasing power, absence -or limited- presence of food production factories, and the absence of export channels. Although some exports have moved from Syria to Turkey, they remain limited in quantity and continuity. Most sellers were left with no choice but to sell their products at unfairly low prices, with a high cost of production and export logistics, leaving them with little if any margins of profit. Such challenges have prevented agricultural production from employing the necessary workforce and strengthening the food cycle throughout the years. The current governance dynamics prevents farmers from securing effective solutions, and therefore the farming community continues to endure losses. This has drastically affected the development of the agricultural sector within these regions.

The following paper covers some of the agricultural sector's challenges and proposes recommendations to empower its sustainable growth. The outlined recommendations may offer some solutions to achieve the minimum level of recovery of costs and create a plan of action.

Accumulated Challenges

The problems faced by the agricultural sector, whether in terms of supply or demand, can be summarized as follows:

Governing bodiesignored the calculations of the absorptive market capacity (demand) of agricultural crops, which increased the financial losses and caused a weak valuation of the sector. For example, based on a 2020 study by the General Organization of the Seed, for onions and potatoes crops, the General Organization for Seed Multiplication estimated the surplus local onions production at 25% and local production of potatoes at 19%. The percentage was estimated without considering the worker's wages, as farmer hardly earns $100 per hectare of onions, while their loss is $1,668 per hectare of potatoes.

In addition to inaccurate calculations, farmers also endure difficulties in exporting produce. Exporting agricultural products from opposition areas to regime-held districts is neither easy nor feasible because of the high transportation costs and bribes to guards at regime-held checkpoints. For example, a kilo of onions in al-Bab area is estimated at the writing of this paper at 200 Syrian Pounds but reaches 500 S.P in Damascus' markets(1) There are also high costs and difficulties in exporting produce from opposition-held territory to Turkey. In June 2018, the opposition areas exported only 4,000 tons of potatoes to Turkey, even though the local production of potatoes was around one million tons. Among the difficulties is the local council’s low capacity to facilitate exports with Turkey. Usually, Turkish authorities show interest in importing commodities from the opposition area, requesting lentils, chickpeas, pistachios, pomegranates, cherries, potatoes and onions, according to their needs in cooperation and coordination with local councilswho mediate between the Turkish government and local Syrian fermers(2)

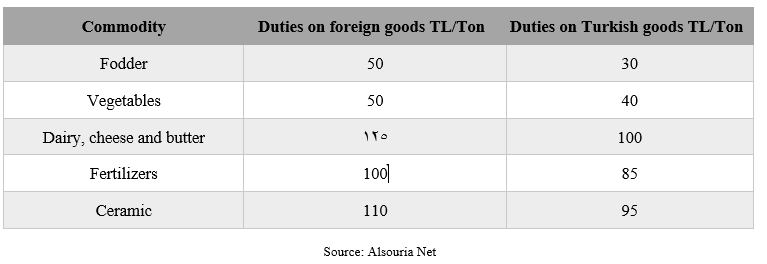

Furthermore, current procedures implemented by Syrian Interim Government do not accurately facilitate the market balance between goods imported from abroad and those produced locally. This leads to the dumping of produce by the local market due to imported items creating a surplus in the market. This became relatively frequent after March 2021, when the Syrian Interim Government reduced customs costs for Turkish goods entering the areas of Aleppo countryside through the Al-Salama, Al-Ra'i, Jarablus, Al-Hamam, Tal Abyad and Ras Al-Ain crossings, as the following table shows(3)

It is evident that the agricultural sector is suffering for a multitude of other reasons. These reasons include the negative impact of the industrial sector, high costs of raw material, lack of accessibility to energy sources such as water, electricity, and fuel, the low purchasing power of citizens, and the unstable security environment. Water has become an issue across the region, but Al-Bab in particular, has suffered from lack of water due to the digging of random wells and draining of the strategic water reserves.

Establishing a National Farmers’ Association (NFA) as a First Step

In order to understand the issues and minimize its negative impacts, there needs to be direct communication and support with non-governmental civil bodies in the agricultural sector. Among those bodies are farmer cooperatives. Communication with both official and non-official institutions to create a strategic plan to regulate agricultural production would achieve national interests and local production and agricultural capital sustainability. To achieve that, the area may establish a National Farmers’ Association (NFA) as a non-profit, non-governmental, agricultural association that brings together local farmers’ associations and agricultural societies and unions scattered in the region outside the government control. The NFA would employ experts and build communication networks across institutions and organizations, such as the Directorate of Agriculture in the Syrian Interim Government, the Organization for Seed Multiplication, local councils, and the Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry, and relieforganizations. It will also be tasked to develop an integrated plan to help such institutions to better manage the agricultural sector in terms of quantity and quality, supply and demand while adopting a trademark for local agricultural crops, health specifications, and quality management that conform to international standards.

To enhance communications, the NFA may issue quarterly reports that include an economic index to measure the growth of the agricultural sector to enhance the values of transparency.

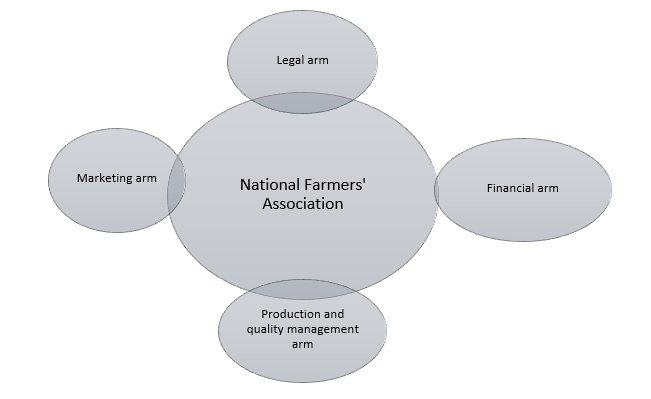

As shown in the figure below, the NFA would be a public body comprised of farmer unions/ associations from every city and town who select a national entity. This new entity would then establish the supporting offices that include: (1) a Legal Office to consider the affairs of agricultural licenses and property rights, control the investment process, issue instruments, and control violations. (2) Marketing Office promotes products and projects to investors and investment entities, negotiates with governments, and signs memorandums of understanding and work protocols to promote agricultural crops and secure consumption channels. (3) Production Management Office that will adapt the production plan to the market needs of food, industry, storage, export and other needs, (4) Financial Office that will be responsible for the transactions, financial liquidity, and the funding and crediting process.

The NFA can preliminarily work in four tracks:

A. Trademarking for Syrian Agriculture

This track includes structuring the agricultural process as a whole and attaining a certificate of confidence from farmers in their willingness to work with the NFA. This process will allow farmers to be included in a registry that will be followed up with regularly.

The other step is to stamp the crop with the NFA's “stamp” to indicate that the product conforms to international health and agricultural specifications. This will enhance the NFA’s control and trust in Syrian communities and abroad. These two steps will motivate the farmer to return to his land and gain greater confidence in both his/her work and product.

B. Regulation of the production process

The failure to consider the balance between supply and demand has led significant increases or decreases in prices. The NFA would intervene to advance the calculations around production to determine the quantity of production, demand, and whether consumption, manufacturing, or exporting, are the necessary response. Through these proper calculations, the NFA would be better able to manage the production process costs and prevent financial losses for farmers eventually.

C. Policy Recommendations to Local and International Actors

Through its reach and capacity, the NFA will be able to issue recommendations on the agricultural sector in Syria to key stakeholders. The NFA would submit recommendations to the Syrian Interim Government, communicating them to relevant governance bodies. This will help enact protectionist policies that limit the import of any product similar to the specifications of the local one, thus reducing the dumping of local produce and harm to farmers. Recommendations may include imposing taxes and duties on every imported product similar to the local product. This will protect the local product, raise its competitiveness, and diversify markets.

D. Product Marketing

For the marketing process, the NFA should focus on two aspects: (1) the legal basis of contracts and covenants for agreements between two parties. The agreement documents will be in accordance with the international legal framework, and (2)the NFA will strengthen the assets of power and negotiation with Turkey on imports and exports to and from opposition areas, including the transit of local products through Turkey’s territory for exports abroad.

E.Developing the Finances surrounding the Agricultural Sector

The lack of financial institutions, such as banks, in opposition areas, has contributed to decreased sources of credit and created a fragile environment for funding and payments. The exchange rate and prices are constantly fluctuating. The NFA can design a financial program that regulates the credit and funding process based on the environment and situation. This includes signing work protocols with organizations, companies and banks, opening bank credits in Turkey and other countries to facilitate the payment and receipt process, and issuing special farming financial instruments(4) to be sold to Syrian investors at home and abroad with the guarantee of the NFA. The NFA can also direct funds to support the food industries sector and various industries in the agricultural sector.

Conclusion

Although establishing a new body is difficult for the local community, it is fairly necessary. The costs of establishing the NFA is minimal compared to the depletion witnessed by Syria’s agricultural sector. The region will reap the fruits of this work, not only by finding nearby and far markets for selling products but also by increasing confidence in the Syrian product, organizing the production process of agriculture, funding food facilities and factories, enhancing the local supply chain, and finally pushing the process of early economic recovery forward. This will present an opposition governance model capable of creating “stability” within a particular aspect

([1]) The farmer sells a kilo of onions for 200 pounds, and the cost of transporting it to Damascus is 300 pounds, Syria TV, 26-01-2021, link: https://bit.ly/3CSLdyA

([2]) Turkey starts importing potato from war-torn Syria, 27-6-2018, link: https://cutt.ly/zRC8lhw

([3]) “The Interim Government” announces a reduction of customs duties of Turkish goods, Alsouria Net website: 14-03-2021, link: https://cutt.ly/XRC3zs3

([4]) Sukuk: Securities from the Islamic Sharia-compliant financing tools. The instrument is linked to specific projects and investment opportunities that are already existed or under construction. The instrument is equal to the value of a share in an ownership, and the holder of the instrument takes profits and has the right to participate in the management, capital, and trading. There are many types of instruments in Islamic Sharia, known as Sukuk (instruments),such as al-Mudaraba, al-Murabaha, al-Istisna’a, al-Musakah, al-Muzara’a, Ijara, services, and others.

Briefing on Latest Developments in Idlib

I. Introduction

Both Turkey and Russia agreed to a ceasefire in Idlib starting at midnight on March 5th,2020. At the time, both sides saw this agreement as representing the least worst case scenario to preserve its interests on the ground and prevent further escalation between different actors. On one side, the Russians and regime forces heavily escalated systematic attacks on civilians and basic infrastructures driving over 1.1 million civilians towards the Turkish borders, hence putting pressure on Turkey and indirectly on Europe. The regime aided by the Russian airforce regained control over vacated villages in the Idlib province and was advancing on more heavily populated areas. On the other hand, after several attacks by the regime against Turkish military forces, the Turkish army heavily escalated its presence and equipment in southern Idlib and broke away with previously agreed “rules of engagement” by attacking regime and Iranian backed forces to stop its advance and prevent further displacement of the civilian population. The agreement hence, was a temporary freeze of operations by all sides. It included the following core elements:

• A ceasefire from the morning of March 6, 2020 along the frontline.

Regime artillery continued to target several locations in the vicinity of the new buffer zone north of the M4, Sources confirmed that 56 violations done by the Regime March 6 to March 31 of the same month.

• Establishing a security corridor six kilometers north and six kilometers south of the main international highway in Idlib "M4," which links the cities controlled by the Syrian Regime in Aleppo and Lattakia, and open an internal crossing between the Regime and Opposition held areas.

Because of the new Corona (COVID19) and the fear of an outbreak of the disease, the interm government in Idlib decided to close all the internal and external borders in Idlib and western Aleppo, but in April 17, 2020 HTS announced its intention to open a commercial crossing with the regime that links both Saraqib and Sarmin, which met with widespread disapproval among civilians and demonstrated near Sarmin objecting to the matter.

• Joint Russian-Turkish patrols to be deployed along the M4 road, starting March 15.

As of April 18, 2020, no full joint patrols were conducted for the entire route for security and logistical reasons. A group of civilians built tents along parts of the road, refusing the passage of Russian patrols, while some military factions took advantage of the situation and worked to further destabilize the security situation. Sources of the Information Unit at Omran Center confirmed that these factions are affiliated with HTS. HTS has been taking steps to indirectly create problems and then present itself as part of the solution in an attempt to legitimize its presence in any future security architecture.

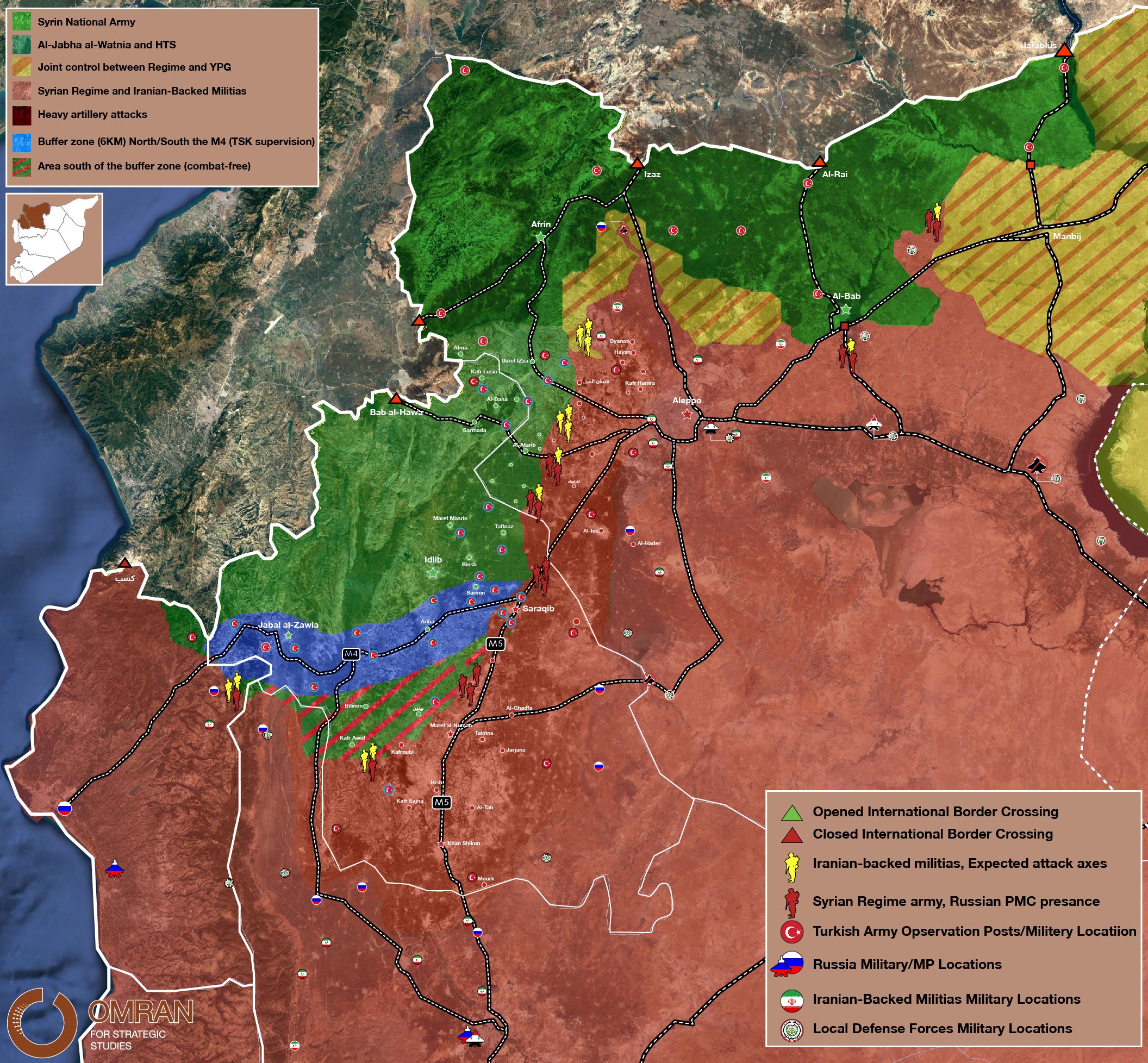

II. Updated map of control in Idlib and its surrounding areas

Updated Control map of Control in Idlib by Information Unit in Omran Centre – 18 April 2020

III. Major developments of the "M4" agreement

A. Turkey’s four current goals

1. Preventing the threat of Corona (COVID19) especially in IDP camps. This can be observed through the strict measures at border crossings, reducing to the maximum interactions with locals, pushing IHH organization to improve its plans, as well as high engagement by AFAD.

2. Increasing Turkish Military posts defense and sending more vehicles and soldiers in the past weeks to establish new posts in Jabal al-Zawyie and al-Ghab Plain.

3. Opposition factions: restructuring National Liberation Front (NLF) by arresting and demoting corrupt commanders, requesting from each faction to call fighters to training camps to compare numbers of fighters and ending any possible connection between groups and other countries in order to ensure order and containment.

4. The M4 agreement with Russia: Turkey is pushing hard for the joint patrols on M4, which has been facing obstacles through sit-in demonstrations by some local actors with direct threats from HTS sub-entities. Turkey is carefully trying to end this situation without using force and by negotiating with the locals. Resolving this situation is a top priority before May in order to prevent any Russian military acts.

B. Positions of local and international actors in Idlib

1. The joint patrols along the M4 highway is Russia’s main priority. There were little if any statements by Russia calling upon Turkey to implement the agreement during February-April, unlike early January. Russia is focusing on dealing with the Corona pandemic and countering increased ISIS threats in eastern Homs, Daraa, and Deir Ezzor.

2. Several news sources indicated that the UAE is pushing the regime to launch a new attack on Idlib and giving promises to fund such an operation. Russia asked the regime not to launch any attack after regime unilaterally and without consulting the Russians sent reinforcements to Idlib.

3. The presence of Iranian-backed militias in Idlib is less than other areas in Syria. However, for Iran to establish a foothold it needs to send more fighters and to launch a limited attack. IRGC-affiliated militias are present in Kafrnabel but are not the main attacking force. Once again, Iran is using its old methods: initial expansion in new areas followed by provision of basic services for local communities.

4. The recent Turkish/Russian agreement put further pressure on HTS by pushing it to re-share power in Idlib with NLF. Furthermore, the Turkish heavy military presence and the deal with the Russians is making Jihadist inside HTS angry and pushing them to breakout. This can be seen in the resignation of Abu Malek al-Talli, and the sit-in protests on the M4 by offshoot members of HTS.

5. HTS has been taking steps to restructure itself, and started by forming 3 new divisions and mixing the hardcore jihadist groups with other less radical members under the leadership of local members.

6. HTS seems to attempts to contain and weaken the more extreme elements within its ranks in order to reduce the risks of possible defections and ensure a future smooth transition from a Jihadi group to a political Islamist group. It is also taking steps to continue its local control over governing bodies such as the Salvation Government.

IV. Future directions

1. There will most likely not be a major regime attack in the near future and even from the opposition side too.

2. May is the month of action for the Turkish sides in order to get ready of the difficult situation surroundings the M4 agreement.

3. The area is witnessing more Iranian-backed militias activities, those activities will increase I. The future in different levels (Economic, Security and military)

4. COVID19 is not the main concern for the local and international actors in Idlib; positive reading is confirmed from the Opposition held areas in Idlib.

Navver Saban | Humanitarian Situation in Idlib

Navvar Saban a Military expert at Omran for Strategic studies talked to TRT WORLD about the dire humanitarian situation in Idlib and possible refugee influx to Turkey. Where Russian and Syrian regime forces seized dozens of towns and villages from northwestern Syria, with the latter vowing to recapture Idlib. That caused mass displacement with more than 235,000 civilians fleeing their homes.

Syrian refuges in Turkey and the current security situation

Navvar Saban, Omran Center military expert and the Information Unit manager participated in a workshop on 20June 2019, about Syrian refuges in Turkey and the current security situation, which is the main reason behind the large number of refugees in Turkey. The workshop title was (The Integration of Syrian Refugees in Turkey) and was organized by (The German Marshall Funds of the United State (GMF) & the Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey (TEPAV)

Saban gave a brief introduction about the security and military situation in Syria in the beginning of his session, and went on to give a deeper clearer idea about:

1) Who are the Syrian refugees (ethnic, socioeconomic, and background)

2) Conditions forced them to leave Syria.

3) Problems they face in Turkey. Why they don’t want to go back.

4) Issues faced in regards integration

Navvar Shaban | What can be achieved by the US Turkey joint patrols near Manbij

On the 09 th of November, Omran Dirasat military expert Navvar Shaban participated in TRT strait Talk show talking about:Turkey has stepped up its attacks on YPG targets in northern Syria, while also conducting joint patrols with the US in areas where the terror group operates.

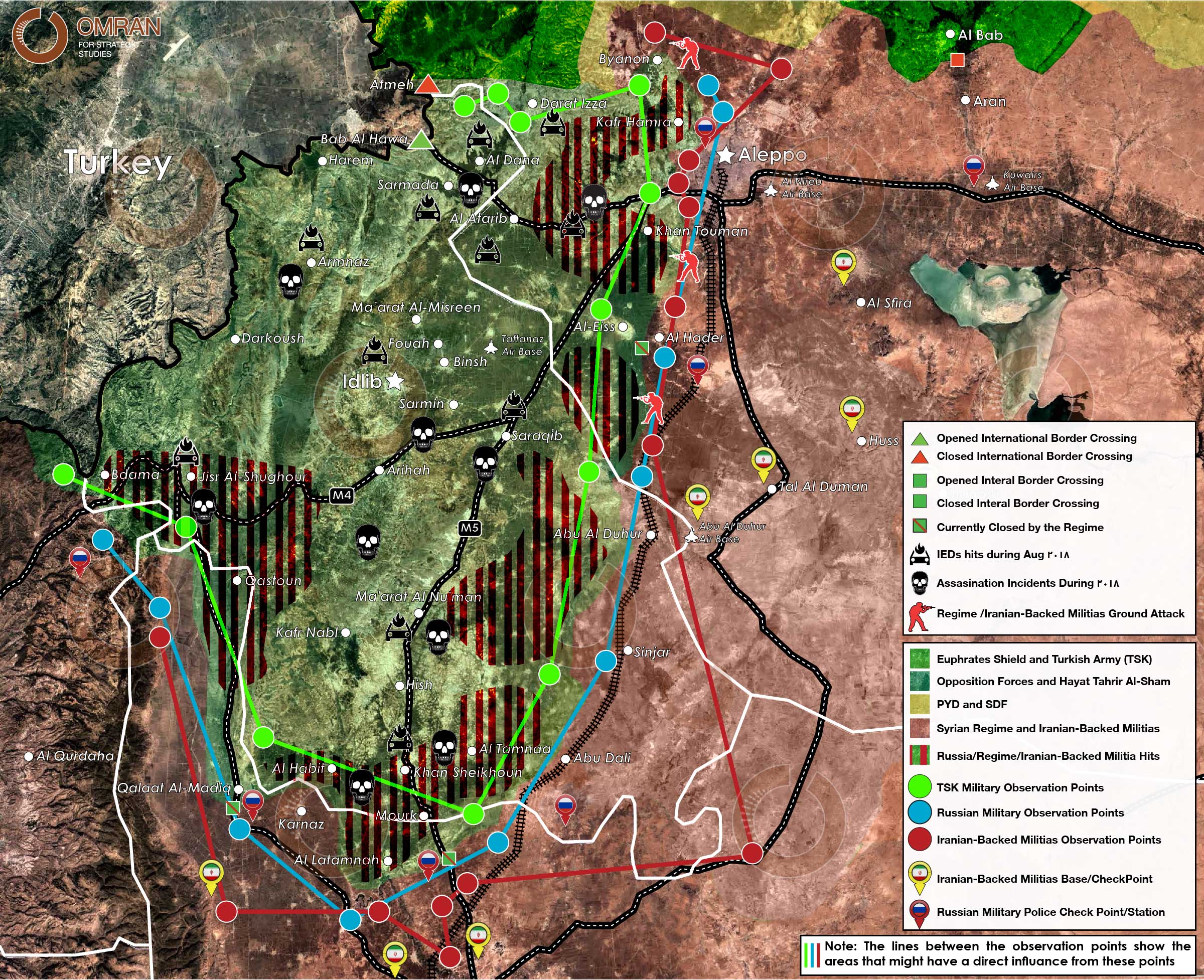

Area of influence Map of Idlib and its surroundings

Map 1: Updated situation map of Idlib, western Aleppo and northern Hama

- Iranian-backed militias’ military bases.

- Russian military police checkpoints around Idlib province.

- International Highways crossing Idlib province (M4 and M5).

- International border crossings with their current operating status and internal border crossings with their current operating status.

- Areas targeted by regime forces, Russian air force, and Iranian-backed militias’ artillery in August 2018.

- Sites of IEDs and assassination incidents that occurred in Idlib and western Aleppo Province in August 2018.

Notes:

- M4 and M5 highways are considered one of the main strategic targets for any possible attacks from the Regime and his Iranian allies.

- Internal border crossings are trading hubs between areas under regime control and areas under opposition control. Currently these borders are closed by the regime for different reasons, except "Qalat Al-Madiq" in Sahel Al-Ghab was partially opened in the last few days to allow the last IDPs convoy from the south to enter Idlib.

- On 13 August, Russian Military Police took over both "Qalat Al-Madiq and Mourek" corresponding internal border crossing sites in regime areas replacing the Syrian Army’s 4th Division (Affiliated with Iran).

Al-Qaeda Affiliate and Ahrar al-Sham Compete for Control in Idlib

"This special report was published byMiddle East Institute , in collaboration with Omran for Strategic Studies, andOPC- Orient Policy Center"

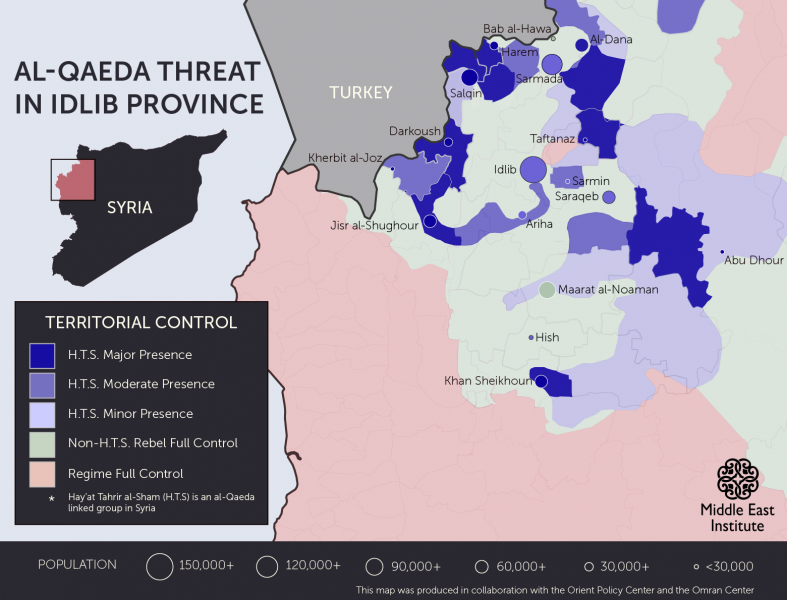

Idlib is currently the site of increasing competition between the two most dominant armed coalitions, the al-Qaeda-linked Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (H.T.S.) and Ahrar al-Sham. The province has witnessed limited airstrikes since a de-escalation agreement, which came into effect on May 5, was brokered by Russia, Turkey, and Iran at the Astana talks. Idlib was one of four areas labeled as a de-escalation zone.

The agreement has, however, prompted a contest between H.T.S. and Ahrar al-Sham, with both groups vying to increase their influence and control new areas. The competition between them has three dimensions: military, economic, and social.

For strategic, economic, and military reasons, H.T.S. has focused efforts on controlling vital towns, specifically along the Syrian-Turkish border on the western side of the province. H.T.S. fighters that shifted to the region from losses in Aleppo and Homs were deployed carefully in areas where the al-Qaeda affiliate wanted to increase influence, particularly along the northwestern border.

The “smuggling” route along the border from Harem to Darkoush is totally controlled by H.T.S., which uses it to transport oil and other goods. The mountainous nature of the area and its many caves also allow H.T.S. to thwart any attack or attempts by Ahrar or any other group to assert control in those territories.

Though H.T.S. controls military bases in the area, such as Taftanaz, to the northeast of Idlib, and Abu Dhour, southeast of Idlib, the group faces challenges in governance. Lacking communal support and strong governing skills, H.T.S. can’t fully control major cities like Idlib, Maarat al-Noaman, and Saraqib. Even in smaller towns like Kafranbel, where civil society has been active, H.T.S. has also failed to maintain a tight grip.

The experience of Maarat al-Noaman is an example of how local communities have played a major role in confronting H.T.S. Since February 2016, civil society has actively mobilized against al-Qaeda’s presence, first against Jabhat al-Nusra, as they were called at the time, and later against present-day H.T.S. The group was unable to control the city or defeat armed opposition groups largely due to the local community’s support for the armed groups. “It is not the armed groups there that protected civil society and the local community, it’s the community that prevented H.T.S. from defeating the armed opposition inside the city,” said Basel al-Junaidy, director of Orient Policy Center.

The only large city H.T.S. has been able to control is Jisr al-Shughour, in part because the armed groups surrounding the city are loyal to Abu Jaber, the former leader of Ahrar al-Sham who defected to H.T.S. earlier this year.

Following increasing pressure from Turkey to protect its borders, H.T.S. delegated to Ahrar al-Sham control over parts of the northwestern border near the town of Salqin. However, H.T.S. still enjoys influence there, and Ahrar still needs H.T.S. approval to appoint the leader of the group assigned to watch the border in that area.

Yet the current map could also be misleading. There are areas where H.T.S. has presence, but struggles to maintain control, and there are areas where it does not yet have a presence, but could expand power if threatened. For example, the main border crossing between Idlib and Turkey is Bab al-Hawa. It is controlled by Ahrar al-Sham, but H.T.S. controls the route leading to the crossing through several checkpoints, and has the capability to attack the border crossing and seize control at will.

In the north, Sarmada is becoming the economic capital of Idlib. H.T.S. controls most of the decision-making there with regards to regulations like money transfers, the exchange rate, and the prices of commodities like metal and oil. On the other hand, H.T.S. is weakest in southern Idlib, from the borders of the Hama province to Ariha, the social base for Ahrar al-Sham.

H.T.S. governs through its General Directorate of Services, which competes with several other entities to provide services. These competitors include Ahrar al-Sham’s Commission of Services, local councils under the umbrella of the opposition interim government, independent local councils, and civil society organizations. A recent study conducted by the Omran Center shows that there are 156 local councils in the province of Idlib; 81 of them are in areas where H.T.S. has a strong presence. As highlighted above, however, H.T.S. doesn’t enjoy equal control over all of these councils. While in some instances the group has comprised whole councils—as in Harem, Darkoush, and Salqin—in other councils, H.T.S. is only able to influence some members.

Due to the de-escalation zones agreement, H.T.S. currently finds itself in a challenging position. When the Nusra Front established its presence in Syria, it promoted itself as the protector of the people. Escalating violence helped the group gain legitimacy and sympathy, and many armed groups found a strong ally in the al-Qaeda affiliate as battles raged against the regime. As front lines become quieter, H.T.S. is beginning to lose its appeal.

The H.T.S. alliance also faces internal threats. The dynamics are changing between Nusra and the Nour al-Din al-Zenki movement, the second largest component of H.T.S. On June 2, Hussam al-Atrash, a senior leader of Zenki, tweeted that areas out regime control should be handed over to the opposition interim government, and all armed groups should dissolve. Atrash justified his suggestion as the only way for the Sunni armed opposition forces to survive. The comments irritated H.T.S. leadership, which referred Atrash to the H.T.S. judiciary. The tweets disappeared shortly thereafter.

Following that incident, H.T.S. banned all fighters from mentioning any subgroup names, like Zenki, to enforce unity. However, it is unlikely that H.T.S. will be able to maintain long-term enforcement. No opposition military alliance has been able to survive throughout the Syrian conflict, and subgroups continue to migrate from one umbrella to another for tactical reasons, seeking military protection and/or new funding opportunities.

While H.T.S. faces these internal and external challenges, it is also evolving. Its leadership clearly realized the importance of building stronger connections with local communities in order to compete with Ahrar al-Sham. H.T.S. adopted new tactics in governing. Instead of appointing foreigners or military leaders, H.T.S. has appointed local civilians as its representatives in most of the towns under its control in Idlib.

H.T.S. and Ahrar will continue to compete in governance and service provision, which is key to building loyalty, increasing influence, and widening public support. The groups are also cautiously following regional and international developments as they prepare for different scenarios. If the de-escalation agreement collapses or an external force intervenes in Idlib, all dynamics will certainly change. Ahrar and H.T.S. might confront each other, become allies, or re-shuffle their respective coalitions. The situation in Idlib is far from stable.

TRT World Interview with Ammar Kahif about Turkey's Euphrates Shield operation in Syria

Dr. Ammar Kahf Talks About Turkey's Euphrates Shield operation in Syria