Omran Center

Official business visits between Iran and Syria 2019-18

Executive Summary

-

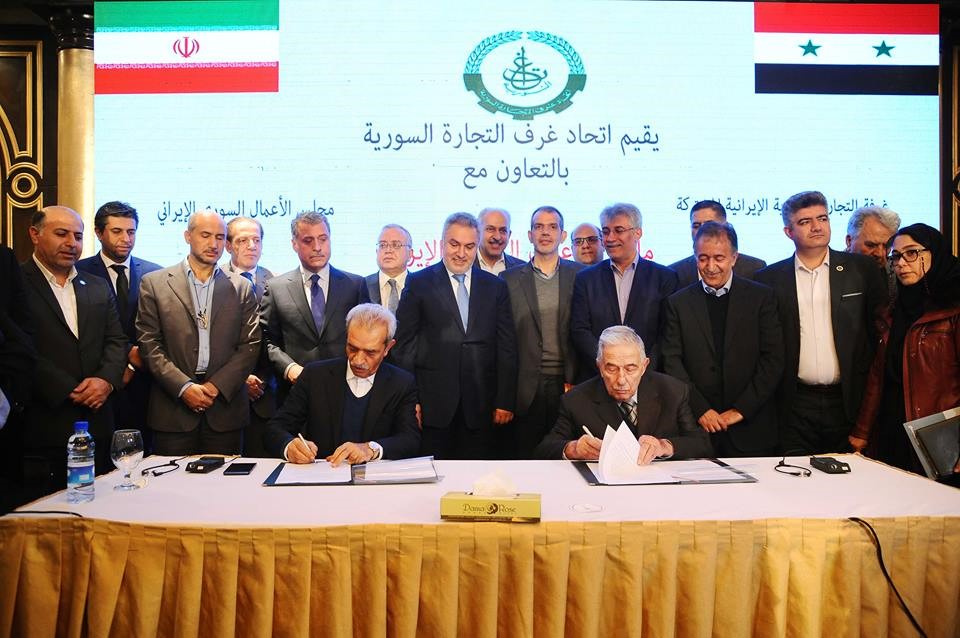

The Syrian-Iranian Business Forum opened in Damascus in January 2019. In attendance were Ishaq Jahangiri, the first vice president of the Islamic Republic of Iran, and Syrian Prime Minister Imad Khamis, as well as a broad swathe of businessmen and company representatives from both countries. This was the first official economic meeting between the two countries that took place in Syria in 2019.

-

In October 2018, a delegation of Syrian businessmen headed by Mohammad Hamsho, secretary-general of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce, traveled to Tehran. There they met with deputy minister of roads and construction for the Iranian cities of Akbar, Fakhri, and Kashan to discuss ways to expand cooperation between the private sectors in Syria and Iran in various economic, developmental, and industrial fields.

-

The 2018 delegation and the 2019 Business Forum events are the key pillars for the development of a stronger economic relationship between Iran and Syria.

-

An economic relationship between Iran and Syria did exist in previous years, but it was largely conducted quietly behind the scenes due to the challenging political and military conditions. With the improving conditions and the re-emergence of the Syrian-Iranian Business Forum, it has become easier for Iran to increase its economic role in Syria.

-

The Syrian-Iranian Business Forum is expected to play an influential role in Syria in 2019. Iran will increase its dependency on local Syrian brokers to do its business in the country so that its activities will not be detected and targeted by sanctions.

This report will provide a brief overview of the October 2018 and January 2019 economic visits between Syria and Iran and what resulted from them. Future reports will focus in greater depth on the Syrian-Iranian Business Forum activities in Syria in 2019.

The Re-emergence of the Syrian-Iranian Business Forum

In October 2018, a 50-person delegation of Syrian businesspersons and Parliament members visited Iran to participate in the Syrian-Iranian Business Forum. The delegation, which was headed by Mohamed Hamsho, Secretary General of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce, met with Iranian officials to discuss customs, investment, stock exchange, development projects, and free trade agreements.

This visit was the first of its kind since 2011. It happened after the Iranian ambassador to Damascus put significant pressure on the Syrian regime to stimulate economic relations and commercial trade between Syria and Iran, especially after the reopening of Syria’s southern Nasib border crossing with Jordan. Tehran wants to use Syria as a terminal to export Iranian goods to Arab markets through the Nasib crossing.

Iran also hopes to build relationships with prominent pro-regime Syrian merchants in order to establish business partnerships and apply for investment contracts. One example is the growing partnership between Iran and the businessman Mohamed Hamsho following the latter's purchase of the Sultan Company's share in the Syrian-Iranian automotive manufacturing company "Siamco.

The Syrian delegation to Tehran followed a number of preparatory visits by Iranian economic and political delegations to Damascus. It also followed a visit by the Syrian Minister of Electricity to Tehran, during which he announced the conclusion of various agreements related to the construction and maintenance of power plants in Latakia, Aleppo, and Deir Ezzor.

One of the most important outcomes of that visit to Tehran was the signing of an MOU between the Syrian delegation and the Tehran Chamber of Commerce for cooperation in various fields. The Syrian delegation also obtained initial approval from the Iranian side to reduce tariffs on 88 different Syrian exports from 4% to 0%.

| Position | State | Name |

| Secretary-general of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | Syria | Muhammad Hamsho |

| Member of Syrian parliament | Syria | Hussein Ragheb |

| Manager of the Federation of Syrian Chambers of Commerce | Syria | Firas Jijkli |

| Businessman | Syria | Hassan Zaidou |

| Syrian Ambassador in Iran | Syria | Adnan Mahmoud |

| Member of Syrian Exporters Union | Syria | Iyad Muhammad |

| Member of Syrian parliament | Syria | Muhammad Kheir Suriol |

| Chairman of the Supreme Committee for Investors in the Free Zone | Syria | Fahd Darwish |

Syrian businessmen who attending the Syrian-Iranian business council meeting

Syria and Iran sign 11 agreements and memorandum of understanding

A number of Iranian officials and private sector representatives visited Damascus in January 2019 for the 14th session of the Syrian-Iranian High Joint Committee. Prior to this meeting, a number of Syrian officials and businesspersons had visited Tehran in preparation. The committee session in Damascus produced 11 signed agreements and memorandums of understanding (MOU) in various sectors:

-

Investment: An MOU for cooperation between the Syrian Investment Commission (SIC) and the Iranian Organization for Investment, Economic and Technical Assistance.

-

Transportation: An MOU between the General Establishment of Syrian Railways and the Iranian railways.

-

Economic: An agreement on long-term strategic economic cooperation.

-

Government: An MOU regarding the meetings of the High Joint Committee.

-

Trade: An MOU between the Syrian Ministry of Economy and Foreign Trade and the Iranian Ministry of Industry, Trade and Mine.

-

Construction: An MOU related to public works and construction.

-

Geomatics: An MOU between the Syrian General Organization for Remote Sensing and the Iranian National Geographical Organization.

-

Entertainment: An MOU for enhanced cooperation between the General Establishment for Cinema in Syria and Iran’s Cinema Organization.

-

Culture: An executive program for cultural cooperation was signed between the Syrian Ministry of Culture and the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance for the years 2019, 2020, and 2021.

-

Banking: An MOU regarding information exchange related to money laundering and terrorism financing was signed between the Syrian Anti-money Laundering and Counter-terrorist Financing Commission and the Iranian Money Transfer Unit.

-

Education: An executive program in the educational field was signed for the years 2019, 2020, and 2021.

Profiling Top Private Security Companies in Syria

Executive Summary

- Before May 2013, private security companies’ tasks and activities in Syria were basically limited to securing shopping malls, banks, and concerts.

- The growing need for legal armed forces not bound by government regulation led to the issuance of Legislative Decree No. 55.

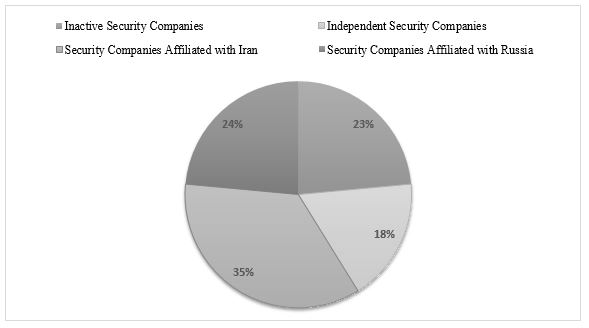

- The Syrian regime’s international allies (Iran and Russia) found what they were looking for in the private security companies.

- Iran used private security companies to institute Iranian presence and influence in sensitive areas in Syria without worrying about whether they can maintain this presence in the future, because private security companies are part of a registered Syrian company.

- Iran used these security companies to maintain presence on the strategic (Baghdad-Damascus) highway in the eastern desert of Syria.

- Russia used private security companies to legalize some local militia fighters that it recruited due to the lack of Syrian army manpower.

- After the reconciliation of some ex-Free Syrian Army (FSA) factions with the Syrian government, Russia had limited choices regarding how it could use these reconciled fighters. At first, Russia used the 5th Corps, which created issues because many Syrian army forces refused to fight alongside ex-FSA fighters. That pushed the Russian military to use these private companies such as the “ISIS Hunters” in order to mobilize and take advantage of the ex-FSA manpower.

Introduction

There are many private security companies in Syria. These companies provide special protection for anyone who needs security services. Some of these companies provide types of services that do not fall under the category of “security” and are instead more like private military operations, such as role played by the “ISIS Hunters” against ISIS in the Syrian desert.

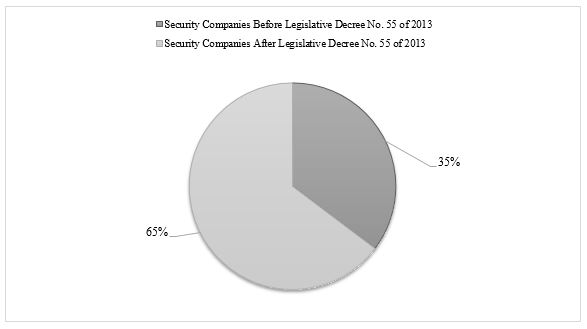

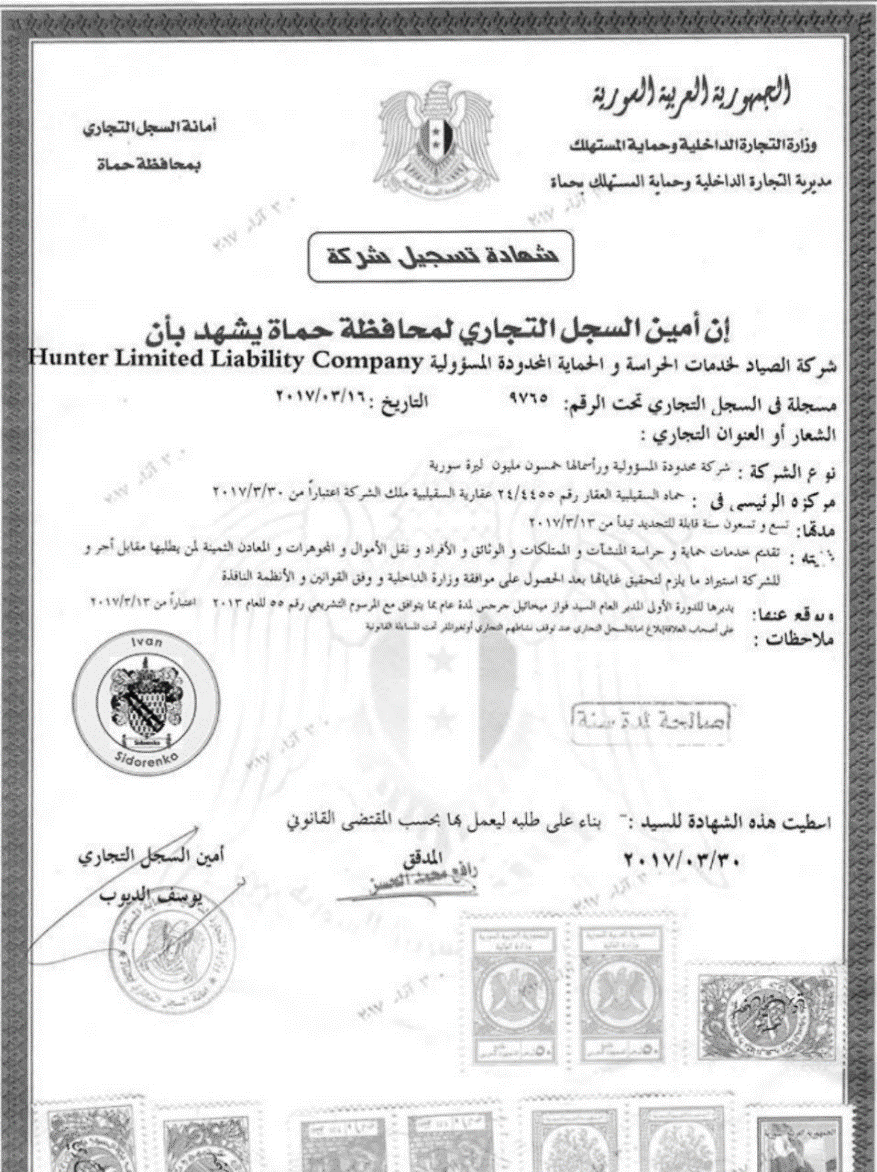

On 5 August 2013, the Syrian president issued Legislative Decree No. 55 regarding licenses for private protection and security companies. Before Decree No. 55, the number of the private security companies in the country was limited. The few private security companies that did exist were primarily funded by well-known businessmen and their main duties were providing security to banks, shopping malls, and sometimes musical concerts. Starting in early 2017, new private security companies began to emerge with much important tasks as well as stronger international allies or even foreign indirect ownership.([1])

Legislative Decree No. 55 of 2013

Agencies and sectors that are concerned with Legislative Decree No. 55:

- Ministry of Interior

- National Security Office

- Companies working in the field of protection, private custody, and the transfer of valuables such as money, jewelry, and precious metals.

In order to receive a license, a private security company must meet the following conditions:

- Be fully owned by holders of Syrian Arab nationality.

- Have capital of no less than fifty million Syrian pounds (SP).

- Its headquarters must be in the same area of operations.

- Be registered in the Commercial Register.

Additionally, the owners, partners, and management of the company shall be required to:

- Have been an Arab-Syrian for at least five years.

- Be at least 35 years of age.

- Have at least a high school certificate.

- Have no expulsion or dismissal from public service on their record.

Private security companies are classified into three categories:

1st category: companies that have 801 guards and above.

2nd category: companies that have between 501-800 guards.

3rd category: companies that have between 300-500 guards.

Top Private Security Companies and their International Allies

| English Name | Arabic Name | License Date | HQ | International Relations |

| Professionals Company | شركة المحترفون | 29 April 2012 | Damascus | Independent |

| Shorouk | شركة شروق | 12 November 2012 | Damascus | Independent |

| Al-Husn | شركة الحصن | 23 March 2013 | Latakia | Independent |

| Qasioun | شركة قاسيون | 28 October 2013 | Damascus | Iran |

| IBS | IBS | 27 November 2013 | Damascus | Iran |

| Al-Watania | شركة الوطنية | 28 March 2016 | Damascus | Russia |

| ISIS Hunters | صيادين الدواعش | 16 March 2017 | Hama | Russia |

| Al-Qalaa | شركة القلعة | 10 October 2017 | Damascus | Iran |

| Al-Areen | شركة العرين | 19 October 2017 | Damascus | Russia |

| Sanad | شركة سند | 22 October 2017 | Damascus | Russia |

| Fajr | شركة فجر | 02 January 2018 | Aleppo | Iran |

| Alpha | شركة ألفا | 15 February 2018 | Aleppo | Iran |

| Al-Hares | شركة الحارس | 08 May 2018 | Damascus | Iran |

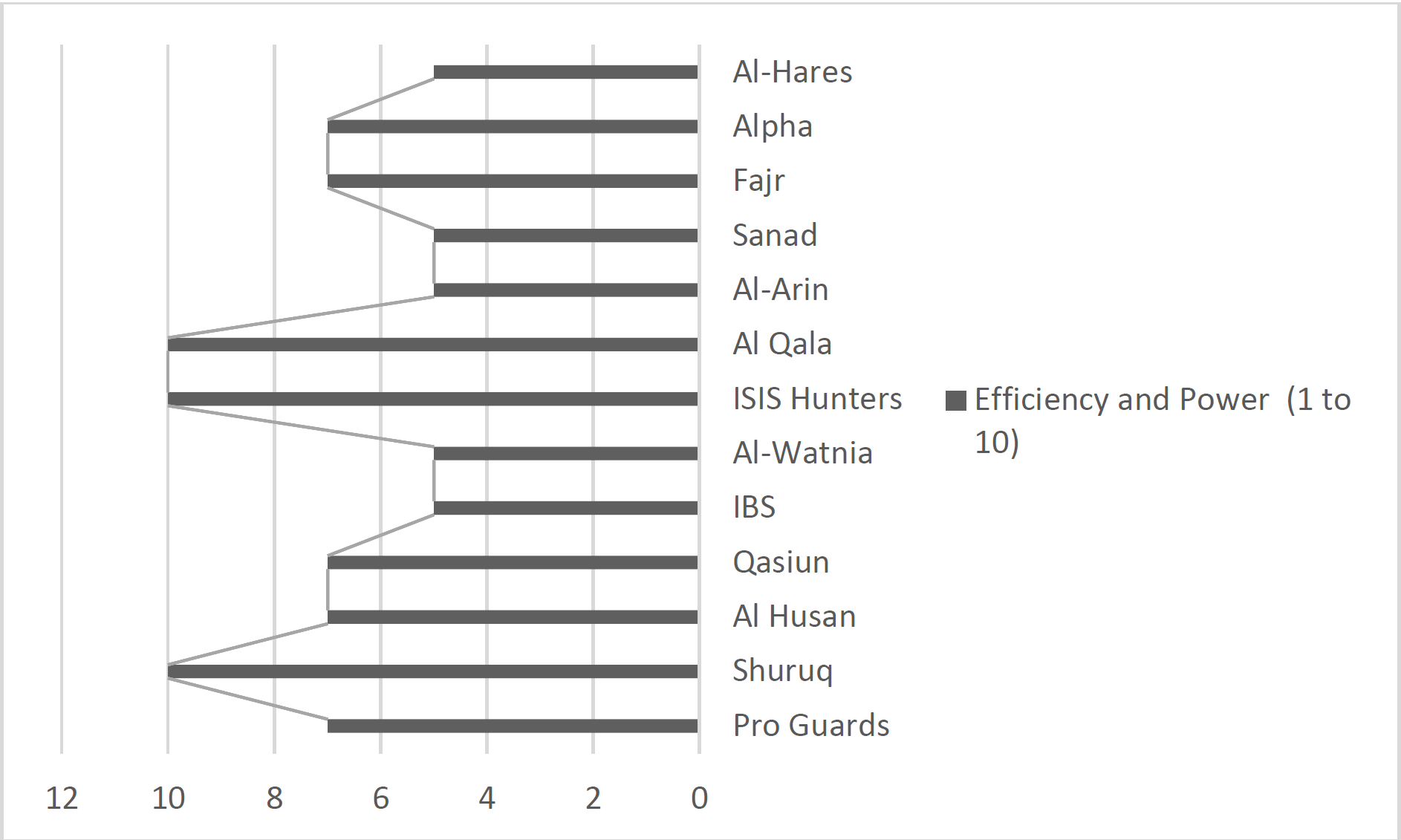

The power of each company is related to the number of secured locations it has, the type of operations it does, and the weapons and armored vehicles that it owns.

Shorouk Company for Security Services (Independent)

Shorouk was established on 12 November 2012. It is run by retired state security officers and its guards have played a major role in suppressing many demonstrations in Damascus. The company has maintained its independence despite the fact that Iran has made several offers to the company’s board members to try and gain their loyalty. Shorouk’s headquarters is in the governorate building in al-Zahra, Damascus.

| Shorouk Company Board Members | |

| Retired Brigadier | General Gamal el-Din Habib |

| Retired Brigadier | Brigadier Ragheb Hamdoun |

| Retired Lieutenant | Colonel Ali Younis |

These officers, known for their good relations with Hafez Makhlouf and Yasser Qashlq, played an essential role in the events of Hama in 1982. The most important of these officers is Ali Younis, who was the most powerful figure in state security before retiring as a lieutenant.

| Main Contracts in 2017/2018 | |

| Name | Location |

| Al-Khair markets | Ein Tarma - Damascus countryside |

| Restaurant and nightclub Areas | Bab Touma in Damascus city |

| Sham City | Kafr Suseh in Damascus city |

| Cusco Mark | Restaurant chain in Damascus and Aleppo cities |

| Ski Land | Shami Village |

| Al-Badia Cement Factory | Abu Shammat area in al-Dumayr |

Shorouk has more than 2,000 employees, including the administrative and security personnel, and they all wear a special uniform with a logo of the company.

The security personnel are paid according to their specific tasks, with a salary range between 1,500 to 4,000 SP per day.

ISIS Hunters (Affiliated With Russia)

ISIS Hunters is a private security company formed, funded, and trained by the Russian military in Latakia to fight ISIS in the Syrian desert on the beginning of 2017, and after that the Wagner group took over responsibility for their training. ([2])

Originally, the ISIS Hunters’ main task was protecting the liberated gas and oil fields in western Palmyra, along with the weapons storage facilities near the T-4 Military Airport.

However, the activities of the ISIS Hunters quickly expanded into combat engagements including the liberation of the city of Palmyra and then crossing the Euphrates to clear ISIS from its eastern bank.

In its initial stages, the ISIS Hunters served more as a private entity within the Syrian Army (Russian military advisor in Khmeimim airbase instructed that) and its only task was to fight ISIS. This role changed after the company’s official registration in March 2017 under Decree 55.

In 2018, ISIS Hunters became more like a private security company but they maintained special privileges to use the army’s equipment because of their initial role fighting ISIS.

After the Syrian military and its allies captured Palmyra in 2017, the Russian-backed ISIS Hunters were tasked with guarding the town against the return of ISIS, clearing the environs, retaking the Palmyra gas fields, and keeping roads such as the Homs-Palmyra highway open. When the Syrian military and its allies lifted the siege of the Deir Ezzor military airport on 10 September 2017, the ISIS Hunters were occupied with clearing the area around Kusham on the east bank of the Euphrates, around 15 kilometers southeast of Deir Ezzor city. On 17 November 2017, the ISIS Hunters announced that they had fully secured Kate Island north of the city of Deir Ezzor and captured 250 ISIS fighters.

Currently, the ISIS Hunter main tasks include: securing the pipelines in eastern Homs, maintaining a presence in al-Talaa Camp in Deir Ezzor, and securing all the checkpoints between the Syrian regime and Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Deir Ezzor province. Their most recent military activity was a very limited role in the battles of Eastern Ghouta in 2018.

Al-Qalaa Company for Security Services (Affiliated with Iran)

Al-Qalaa Company was established on 10 October 2017 and is managed by the Syrian businessman Mohammed Dirki. Like several other similar companies, in the beginning al-Qalaa had a very limited scope of work. In February 2018, a group of security men and women from al-Qalaa in black uniforms equipped with small machine guns were spotted in the Sayyida Zainab Distract of Damascus. Their main role was to secure a Shi’ite convoy from Iran, Lebanon, and Iraq that was visiting the Shi’ite holy sites. Iran’s main reason for creating and funding al-Qalaa was to protect these pilgrimage convoys, after several incidents in which Shi’ite convoys were targeted by in improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in Damascus city.

After the Syrian military and its allies recaptured more of the Syrian desert and Eastern Homs Desert they simply required more forces to secure these areas, in April 2018 the Syrian Interior Ministry (and Russia) approved al-Qalaa to be equipped with advanced weaponry in order to assist other groups such as the ISIS Hunters in securing the road, pipelines, and other locations in the desert.

Immediately after al-Qalaa was granted this contract, they received 25, 4x4 advanced trucks equipped with heavy machine guns, and were deployed to eastern Homs, southern Raqqah, and parts of the main Deir Ezzor-Homs highway.

Short Promotion video published on April 2018, https://goo.gl/c9ErhM

During the 2018 Damascus International Fair, al-Qalaa general manager talked about how the company had expanded their services and starting in May 2018, they provided the following:

- Protection of facilities.

- Protection of Shi’ite convoys.

- Protection of commercial convoys.

- Engineering Unit.

- Anti-Narcotics Unit.

- Emergency Unit.

- Support Unit for military operations.

([1]) Indirect ownership: the company only provides security tasks for Iran and Russia, despite being owned and managed by Syrians.

([2]) "Wagner group" is a Russian paramilitary organization associated with Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch and close associate of President Vladimir Putin. Vagner commanders have fought for the company both in Syria and, before that, in support of Russia-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine.

Transformations of the Syrian Military: The Challenge of Change and Restructuring

Executive Summary

- Throughout its history, the Syrian military has gone through a number of stages in its structural and functional evolution. These include processes undertaken based on the need to develop the military’s professional and technical capacity, or as required for the domination and control of the regime over the army, or as dictated by the war conditions. But since Hafez al-Assad took power, the military has become a major actor in local “conflicts,” whether as a result of the social composition of the military and the sectarian engineering efforts started by Hafez al-Assad and continued by Bashar al-Assad, the special privileges granted to military members, or as a result of the military doctrine that is customized for the preservation of the regime and not based on national ideals. Some of the most significant structural and human changes in the history of the Syrian military took place between 2011 and 2018. These shifts included the entry of auxiliary non-Syrian forces, both individuals and groups, which completely changed the role of the “army” from that of a traditional national army into a force used primarily to protect the ruling regime.

- As a result of the unexpected outbreak of military operations across the country against a popular uprising, there was a significant increase in the number of amendments made to laws governing the military establishment in order to address gaps in those laws. Some of the laws were ignored in favor of custom and tradition. This was reflected in the promotion and evaluation of officers based on sectarian or regional affiliations. The introduction of a partial mobilization in Syria without official certification of the decision as a result of the events starting in 2011, and the issuance of a new mobilization law at the end of 2011, supported the regime's efforts to distribute mobilization tasks to all state institutions and departments. Previously, the last law on mobilization had been issued in 2004.

- At the outset of the uprising in Syria, the military's deployments were characterized by complete chaos. The regime's use of local and foreign militias, in addition to the Iranian and Russian regimes, transformed this deployment from complete chaos to a more organized chaos. The regime was able to recapture many villages and cities based on a strategy of collective punishment, scorched earth offensives, and guerrilla warfare. The Syrian regime's use of local and foreign militias led to an imbalance in the structure and responsibilities of the army during the revolution, so that the military became a more Alawite-dominated institution because of its reliance on its Alawite members. Most of the officers were corrupt, and that corruption became much worse during the years of revolution, causing the military to become increasingly distant and isolated from society. This pushed the officers to collude with corrupt networks within the regime and to exploit them to achieve further gains and accumulate wealth.

- In 2018, the military landscape witnessed many major transformations, most notably the division of the country into three main international spheres of influence, each of which contained a diverse mix of local political powers. In the first sphere controlled by the regime, there were indicators of increased Iranian and Russian influence, as well as an attempt to consolidate the militia scene, with some being dissolved and others linked to Iran being integrated and merged with others. In the second sphere: includes the armed opposition forces in northern Syria backed by Ankara, the map of relevant armed actors became more disciplined and contained under the framework of the Astana talks. Opposition forces displaced from southern and central Syria were restructured by Ankara in support of the Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch operations. In the third sphere: the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) continued to perform their security and military functions under the self-administration project and its legal framework. At the same time, their negotiations with the Assad regime continued, leaving their options wide open and making it more likely that the situation would get more complicated because of the lack of a clear policy from the Americans who supported the SDF on the one hand and pushed for further negotiations on the other.

- The regime’s attempts to reduce and contain the roles carried out by Iranian and local militias were not comprehensive or well organized. On one hand, many Iran-backed militias became integrated into the official regime military structure following the formalization of Iranian operations in Syria, which did not reduce or contain its power or impact. On the other hand, the overall reintegration strategy was not adhered to especially with regards to local militias or groups that settled through reconciliation agreements, as the objective of conducting operations against opposition forces is still prevalent and dominating deployments. This process of reintegration will face further obstacles that will greatly hinder any restructuring process as a result of the deep infiltration of such militias and the diverse roles they play in society and within the security sector.

- The data and indicators examined by the papers contained in this book highlight the deep and significant impact of transformations in the military institution both in the medium and long terms. These transformations are observed in the structural and functional imbalances of the military institution especially as it faces a deficit of power, capacity, and resources. Furthermore, the regime’s military institution has become one of many other actors in the scene and often held hostage to local and international networks of power, whether it is the Russian or Iranian or other local groups. It is also restricted in its capacity because its imbalanced societal composition, has not adopted political neutrality, and the ideological party doctrine that dominates. All this necessitates a rebuilding strategy that is absent from the current regime’s agenda as well as its allies in favor for superficial rehabilitation for the purpose of regaining control of territory and society.

- In the face of the current frame of reference that guide the reform course of the military institution, the absence of a national agenda or vision should be noted. This vision should stipulate the requirements for the reform process, most important of which is the political process and change, depoliticizing the military institution, protecting political life from military interferences, and the reinforcement of healthy and normal civil-military relations that enhance its performance.

Introduction

Based upon the need to redefine the roles of the Syrian military institution in light of the profound transformations in the concept of nation-state, Omran Center for Strategic Studies launched this research project to further analyze those transformation and address the challenge of change and restructuring. The approach first deconstructs and assesses the functions and structures of the Syrian army, its doctrine, and causes behind its involvement and interference in social and political affairs in accordance with the regime’s philosophical vision of domination and totalitarian control. The papers contributed by researchers in the first phase of this project are as follows:

- The Syrian Army 2011-2018: Roles and Functions

- Military Actors and Structures in Syria in 2018

- Stability and Change: The Future of the Military in Syria

- Annex Report 1: Significant Transformations in the Army: 1945-2011

- Annex Report 2: Laws and Regulations Governing the Military After 2011.

The outputs of papers and reports in this book assess indicators of instability in the map of military actors and measure its impact on the centrality of defense and security functions and the future end game for the nodes of power within the military after possible reintegration processes. It also focuses on the relationship between the military and political spheres, in the sense that it evaluates the potential for military actors to contribute to various avenues of reform, including the redistribution of power in a legally decentralized manner. Similarly, it also looks at the changing political situation and the positions taken by regional and international backers of armed groups, which influence the decisions of military actors, leaving them with limited options.

This book first outlines the main historical developments in the Syrian military in order to establish a more comprehensive understanding of the shortfalls in the military structures and how they developed. It also looks at the most important laws and amendments related to the military establishment and how they have evolved over time. The book also describes how the military leadership used these laws after the start of the Syrian revolution to recruit fighters to the military that were completely loyal to the ruling regime.

The papers and reports in this book try to answer a number of key questions such as: does the military in its current state embody features of effectiveness, adopt a national outlook, have the capacity and ability required to preserve and promote the outputs of a political process, and able to create and promote conditions for stability? Addressing these questions necessitated first to recognize the positioning of reform policies within the current and future military institution agenda, and to assess the presence or lack of a cohesive and stable structure after the profound transformations it witnessed. Finally, the book outlines an initial vision for a framework for reform that would allow this institution to be a catalyst for societal cohesion and adopt a politically neutral position to become a source of stabilization is Syria.

Omran Center plans to launch a second phase with additional papers to be based on the outcomes of papers contained in this book as well as discussion and feedback received from participants in the workshop held in Istanbul on October 25th, 2018 to focus potentially on the following topics:

- Sectarianization mechanisms in the Syrian military.

- Power nodes and networks in the Syrian military.

- Management of surplus manpower: a case study of the 4th and 5th corps.

- The military judicial system.

- Non-technical challenges in the reform of the military establishment.

For More Click here

An Assessment of Idlib DMZ after 75 Days

Introduction

On 7 Sep 2018, when the Tehran talks ended between Turkey, Russia, and Iran it was obvious that there was no final agreement or disagreement amongst the Astana international players. Everything became more vague except for the postponement of any ground operation by the Regime and it’s allies against Idlib and its surrounding. The Russians decided to postpone any ground attack for the following reasons:

- Buy more time for all the Astana actors to reach for a deal that suits everyone and serves them in a way that does not affect each other's.

- The lack of manpower that is loyal to the Russians in the northwest and that are needed to fill Idlib in case of a ground attack, which will give the chance for the Iranian-backed militias to expand their control to Idlib and Western Aleppo.

Prior to the DMZ agreement, both Turkey and Russia committed to taking several steps in Idlib, which formed the solid base for the initial step of the DMZ. Following are the most significant actions done by Turkey and Russia during the first two weeks of Sep 2018:

- The Turkish observation points cleared their surrounding from any Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) presence.

- Turkey informed al-Jabha al-Watnia factions to stop coordinating with HTS and not to form any kind of joint military operation rooms.

- Russia announced that it took control of the three internal crossing borders between regime and opposition areas "Abu al-Duhur, Mourk, and Qalat al-Madiq," and informed the 4th division and LDF forces to evacuate the area.

The DMZ Specifications

On 17 Sep 2018, Putin and Erdoğan held a meeting regarding Idlib and agreed to establish a DMZ in Idlib, Northern Hama, and Western Aleppo with the following specifications:

- 15 to 20 km zone running along the borders of the Idlib region will be safe from Syrian and Russian air force attack and will be in place by 15 October.

- Heavy weapons including tanks, mortars, and artillery will be withdrawn from the zone by 10 October. ([1])

- This agreement will prevent a large-scale Russian/Syrian ground attack on Idlib and its surrounding.

The agreement was at the time of the announcement the best case scenario for both Turkey and Russia, but mostly it is important for 3.5 million civilians living inside Idlib – on paper the agreement is solid but implementing will not be an easy task.

The DMZ under the Test

The agreement faced many challenges even before it started, several point needed to be addressed by the Russians and the Turks before October 2018. Following are the most threats that directly or indirectly affected the DMZ in OCT and NOV 2018:

-

Al-Jabha al-Watnia are not the only ones who control Idlib and its surrounding, several factions have large presence in the area, and some of them are considered extremists (HTS, Huras al-Dien, Ansar al-Islam – the region also has independent FSA factions, independent jihadist factions, ISIS cells).

-

The Salvation Government which is affiliated with HTS, administratively controls 75 locations (Cities and Villages) in Idlib and it’s surrounding.

-

The Turkish borderline with Syria is totally controlled by HTS including Bab al-Hawa – also HTS controls 2 out of 3 internal border crossings with the Regime areas inside Idlib. Controlling the crossing gate means sizable Income.

-

The Iranian-backed militias have a large presence in Aleppo province and in Northern Hama which the Russians had to insure that their presence would not cause future problem, which as expected didn’t happen, the Russian couldn’t reduce the amount of the Regime and Iranian-backed militias artillery attacks on the DMZ and couldn’t even prevent several ground attacks by them

HTS official statement in regard of the DMZ

On the 14th of October, HTS published a statement clarifying their position regarding the DMZ. ([2]) The statement was vague and didn’t include direct decisions. HTS mainly tried to achieve the following from this statement:

- Win more time to try fixing its own structure and solve the problems between the Syrian and non-Syrian fighters within HTS.

- Give positive signals by seeming to appreciate the efforts and not being a spoiler yet warning against Russian tricks or manipulation.

- HTS warned against any Russian tricks in regard to the DMZ, by that they implied that they accept the deal but do not want to anger the Jihadi side whom HTS gave positive signals to in the first point of the statement about holding on to Jihad

- HTS mentioned the populist protests and said it will give a final decision on the agreement after meeting and consulting with revolutionary sides; this is to show that they supposedly don’t have a problem with the civic movement in Idlib anymore.

HTS extremists, partly led by the Egyptian "Abu al-Yaqzan", refused to accept the DMZ agreement especially because of regime violations and continuous attacks in Hama northern countryside and Western Aleppo countryside where HTS clashed with al-Jabha al-Watnia and captured 25 fighters (majority from Ahrar al-Sham).

Major incidents in the DMZ and surrounding area from 17 Sep to 10 Nov

- 18 Sep 2018, southern Idlib and northwest Hama witnessed 9+ attacks by regime artillery after the signing of the Russian and Turkish agreement. All the attacks happened in the DMZ and caused the death of 13 civilians.

- 21 Sep, A major explosion occurred in the Hamdaniyah district of Aleppo city. Regime media accused opposition groups of targeting the Military Academy.

- 23 Sep, Hurras Al-Din published an official statement rejecting the Turkish and Russian DMZ agreement.

- 06 Oct, Al Jabha al-Watnia started to withdraw its heavy weaponry from Kafr Naha in western Aleppo.

- 06 Oct, Heavy clashes between HTS and al-Jabha al-Watnia (JWT) in Mirnaz village, causing the death of Seven JWT fighters and five HTS fighters.

- 16 Oct, (Huras al-Din, Ansar al-Din, Ansar al-Tawhid, Jamaat Ansar al-Islam) formed a new operations room to continue fighting against the regime and the Iranian-backed militias, These four factions are listed as extremists.

- 21 Oct, JWT repelled an attack from the LDF and 4th Division fighters near the village Kherbet Al-Naqus in Sahel al-Ghab at Northern Hama.

- 25 Oct, JWT repelled an attack from al-Quds Brigade (LDF) near Kafr Hamrah in western Aleppo.

- 29 Oct, Regime forces bombed Mourk city for the first time since the DMZ agreement. The Turkish Observation Points (OP) is only 0.8 KM far from the city.

- 01 Nov, Jaish Abu Baker (HTS) carried out an attack against a regime location in the eastern Idlib countryside. Pro regime news agency announced the death of six soldiers.

- 02 Nov, The Mourk internal crossing (located on M5), between the opposition & regime controlled areas was reopened. The crossing is controlled by the Salvation Government from the opposition side, and by the 4th Division and Russian Military Police on the regime side.

- 08 Nov, Twenty-three fighters from Jaish al-Izza were killed after the regime and Iranian-backed militias attacked in the village of al-Zilaqiat in northern Hama.

- 09 Nov, JWT launched an attack against the regime position in Mhardeh, killing at least six soldiers from the 5th Corps & 2nd Brigade.

- 10 Nov, HTS "al-Easayib al-Hamrah" launched an attack against regime positions in Halfaya in retaliation for the attack in al-Zilaqiat.

- 10 Nov, Hezbollah participated in al-Zilaqiat attack but until now they didn’t announce any death among their fighters and even if they did they won't declare on which front the fighters were killed.

- 16 Nov, Huras al-Din launched an attack on regime locations near Jurin in Sahel al-Ghab.

- 24 Nov, Regime forces used heavy "240 mm rocket" while targeting Jarjanaz in Idlib, which is part of the DMZ (3 children & 2 women killed).

- 24 Nov, Pro regime news agency reported a gas attack in al-Khaldia district in Aleppo, The substance is currently unknown and it resulted in no deaths so far, with 41 injured according to the regime's state media.

- 25 Nov, Russia warplanes conducted 21 raids on western and southern Aleppo; it was the first Russian attack since 17 Sep the day of the DMZ signing.

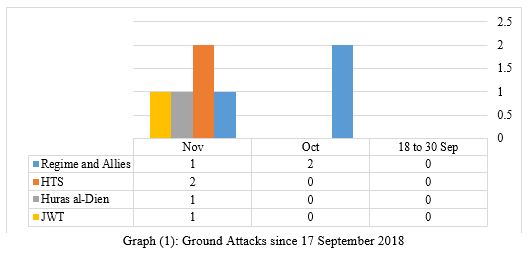

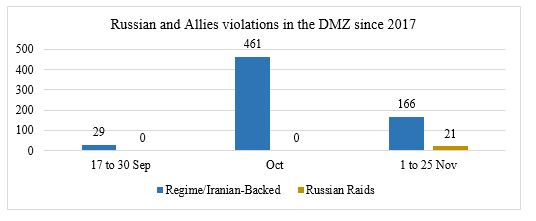

Below is a graph of the violations from the regime and Iranian-backed militias as well as the opposition forces and other groups inside Idlib and its surrounding:

Conclusion

The Sochi agreement regarding the situation in Idlib between Turkey and Russia should be considered as an interim agreement imposed by considerations of the situation on the ground and the western / American refusal of any large-scale Russian operation in Idlib. From the Russian point of view, the agreement is a tool for managing the Russian-Turkish relationship on the one hand, as well as to test the western / American position on the other hand. For Turkey, the agreement serves as a tool to contain risks and minimize losses and to a lesser extent a bargaining tool with Russia and America. The Sochi agreement is under extreme pressure, as Iran is actively working to be part of this agreement by exerting pressure on the ground through its militias, like the Zalaqiyat, in north Hama. The internal situation in Idlib has contradictions that seem to be fairly under control so far but this does not eliminate the possibility of exploding at any time via the external stimulation or the result of conflicting calculations (gain and loss) of local forces.

Despite the foregoing, the Sochi agreement is not expected to collapse in the short term, although it may have changed in terms of its parties and field actions, and the foregoing does not eliminate the possibility of limited changes in field control in specific areas, or may alter the field arrangements in those areas; nor will it eliminate the persistence of mutual violations, which reinforce the above-mentioned Russian-Turkish coordination following the recent targeting of Aleppo.

The Turkish-American relationship is not in harmony with regard to the East Euphrates and Manbij, which leads Turkey to resort to the Russians and push Moscow to maintain this agreement.

([1]) 18 September 2018 – The Guardian - https://goo.gl/LC8YeU

([2])Daily News – 15 Oct 2018 - https://goo.gl/yBu41X

Navvar Shaban | What can be achieved by the US Turkey joint patrols near Manbij

On the 09 th of November, Omran Dirasat military expert Navvar Shaban participated in TRT strait Talk show talking about:Turkey has stepped up its attacks on YPG targets in northern Syria, while also conducting joint patrols with the US in areas where the terror group operates.

Emerging Security Dynamics and the Political Settlement in Syria

Omran Center for Strategic Studies collaboration with The Syracusa International Institute, held a workshop on “Emerging Security Dynamics and the Political Settlement in Syria” in Syracusa, Italy, on 18-19 October.

The workshop brought together experts from UN, EU, France, Germany, Switzerland, US and many regional countries. The vibrant discussion tackled various issues including: future of the DMZ agreement in the north, the logic of the Iranian presence in Syria, the political economy of militias, and local security imperatives impact on peacebuilding.

This workshop is the one of many workshops hold under "The Syria and Global Security Project" who is co-run by Omran Center for Strategic Studies and Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP). It aims to offer a platform to build common ground and bridge the gap between the main stakeholders in the Syrian conflict.

Centralization and Decentralization in Syria: Concepts and Practices

Introduction

After seven years of conflict between the people and the Assad regime, Syria is now going through a difficult phase. The nature of the conflict has transformed whereby the role and effectiveness of local actors has been greatly maringalized compared to an increasing role for international state and non-state actors. The role of armed opposition factions has diminished as international military, administrative, and political influence has grown. These armed opposition actors are also in a phase of turmoil as they struggle to survive or integrate under direct international custodianship, after having previously received support from the Northern or Southern Operations Rooms. This process follows the series of meetings in Astana and Sochi, and after the political bodies were domesticated into official negotiating bodies that support the interests of countries with direct influence over them. At the same time, direct Russian influence came to dominate the political, military, economic, and administrative spheres. As a result, the concept of the unified framework of the "regime platform" versus the "opposition platform" in accordance with the Geneva II concept was discarded through the creation of several negotiating platforms on the sides of the opposition, the regime, and the Syria Democratic Forces (SDF).

At the same time as these political changes were happening, the areas of influence and control on the ground were consolidated in 2018 into the north and northwestern portion under Turkish control, the northeast under the U.S. and SDF control, and southwestern Syria under the influence of the U.S. and Jordan, allowing Israel to strike any sites that it deems threatening. The areas of siege and opposition group control have been eliminated. International and regional influence has thus become more distinct, as efforts to control and integrate both armed opposition and pro-government groups continue.

This new phase is characterized by a complex series of partial deals that build on one another, and the arrangements among the state actors are developing in a "step by step" policy approach. The "counter-terrorism" framework that was used to justify the entry of these countries into Syria, is no longer a justification for their continued presence and influence: the U.S. is increasingly focused on the "Iranian threat;" Turkey is focused on "fighting the PKK" and security its borders; Israel justifies its interventions with the need to protect its borders against the "Iranian threat" and to prevent the transfer of weapons and fighters toward its borders; and Jordan is now also interested in protecting itself against the “Shi’ite crescent".

In light of this new landscape, contributing writers to this book discuss several aspects of Syria's current form of governance and how experiences on the ground in the different areas of influence converge or diverge from the concepts of centralization and decentralization, both vertically and horizontally. Towards this end, the chapters of this book first clarify the concepts and forms of decentralization and the way they are applied in post-conflict countries. They highlight the important role that agreeing on the form of governance and power sharing is an important factor in maintaining territorial unity and in shepherding negotiations to a more relevant stage of the new post-conflict reality. Next, the authors delineate decentralization in terms of its political, security, financial, and developmental functions, and review the constitutional and legal foundations of administrative and political decentralization in Syria. Finally, the authors present the experiences and applications of governance since 2011 in the regime-controlled areas and opposition-controlled areas, as well as in the SDF-controlled in northeast areas of the Democratic Autonomous Administration. Woven throughout the book are comparative descriptions of the experiences from Iraq, Lebanon, and other countries emerging from conflict, to see what lessons can be learned from the ways that these countries have negotiated the distribution of powers between central and local administrative units.

This book aims to help lay out a path towards the restoration of the legitimacy lost by all parties in Syria through the organization of local governance tools based on the experience of local councils. Local councils have tended neither towards excessive forms of decentralization nor to authoritarian centralization, but have instead followed a path that strengthens local structures and sets limits to central state authorities by granting powers rather than delegating them. At this stage, it is essential to work in parallel on strengthening the central government while also safeguarding and reinforcing the gains of the local councils through constitutional guarantees and a new local governance law. This book also stems from recognition of the need to shift away from limited centralized negotiations among the two “sides of the conflict” through a constitutional process followed by general elections, towards a negotiation based on power-sharing arrangements. Local governing bodies and other local actors should be engaged in the process of deciding which functions and authorities are mandated to the central institution versus the local governing units.

The chapters of this book were contributed by several researchers who differ in their approaches, but they all agree on the need to develop a decentralized Syrian model that avoids the reductive binary approach of political decentralization / administrative decentralization or federalism, and one that is based on the sharing of powers and functions, thus transitioning Syria’s system of governance from local administration to local governance. There is no doubt that further development and discussion of these ideas is required, but we present this effort as a starting place for a dialogue in the Syrian community on the most authentic or locally developed form of governance for Syria, which after years of adhoc decentralization, has become more localized than ever before.

Finally, it is important to note that most chapters were written in late 2017 and early 2018, which was before the change of control of Damascus suburb, northern Homs and the southern front. The arguments for a tailored and customized Syria-centric decentralization model put forth are still valid regardless of the controlling armed party.

Executive Summary

Chapter one of the book focuses on the concept of decentralization and illustrates the differences among countries when it comes to choosing how they exercise administrative authority. Every country’s approach to governance is influenced by its political and social conditions, as well as the maturity and depth of its democratic practices. The need to shift towards a decentralized system becomes apparent after examining factors related to a state’s nature, size, and degree of political stability. Decentralization becomes a necessity for stability in some countries because of its core idea: the distribution of power and functions of state institutions between the central governments and local administrative units. This conceptualization reaffirms the fact that the transformation to fully decentralized system may be risky for many governments, despite the promise that decentralization holds as the solution for most conflicts in developing countries such as those in the Arab world. Chief among these problems is the need to expand the political and economic participation of citizens. Still, given the ethnic and sectarian diversity and complex nature of countries, decentralization can be a threat to state unity.

Chapter two describes political functions of the state in a decentralized system and how it is practiced in different versions of decentralization. Political functions of the state take many forms depending on the degree of decentralization and mode of local governance. The far end of a decentralized governance system continuum appears in the practice of full political decentralization (full federalism), where provinces and regions have their individual constitutions and laws, exercise special legislative, executive, and judicial powers, and influence federal government policy through a political oversight authority and through their representatives in the legislative branch councils. Local governments, meanwhile, exercise specific roles in these functions under the partial political decentralization within their constitutionally-vested authority. These roles are primarily related to domestic policy-making and the development of local rules and regulations that do not contradict federal legislations. In administrative decentralization modes of governance, the practice of political functions and duties is reduced to a great extent as it focusses exclusively on administrative and executive functions of local governing institutions. Local administrative units would then be fully subordinated and controlled by the central administration in the capital. In partial administrative decentralization modes of local governance, political functions completely disappear from local units.

According to chapter three of this book, the exercise of legislative and judicial functions within a decentralized system will require reforms in the Syrian judicial branch, such as: the restructuring of the Supreme Judicial Council to ban the executive branch from holding membership in it and stop its interference, and the repeal of laws that encroach on public rights and freedoms with judicial not executive branch oversight. Assessing the current form and content of the Syrian Constitution in terms of centralized or decentralized approaches highlights centralism as highly visible and grants authority to the presidency (which has broad constitutional powers) to override all other authorities and functions of the state. Instead, the principles of separation and distribution of powers should be applied to three independent bodies in order to create balance and cooperation between them. With regard to legislative duties in Syria, this paper shows that the Constitution has broadly granted legislative duties to the People's Council of Syria (Parliament) and the President of the Republic, transforming the mandate of the Parliament from drafting laws to ratification of presidential laws. Reforming this imbalanced structure requires redefining the scope and mandate of the Parliament, abolishing the broad powers granted to the President, and reducing the centrality of legislation process and parliament. There needs to be a shift toward some kind of decentralization that divides future legislative functions in a balanced approach between the exclusive jurisdiction of the legislative branch, and the jurisdiction of the executive branch for all that is not stated in text of the constitution.

The fourth chapter focuses on security functions in decentralized systems. In the context of conflict-ridden or post-conflict countries, it is critical and necessary to re-assess national security functions: their applications, mechanisms for implementation and governance, and how security roles are distributed at different levels of government. This paper emphasizes that the redistribution of security duties and authorities in decentralized countries (in accordance with the lessons from stable and unstable countries) may result in a more efficient and coherent security architecture depending on who and how such a process is executed and whether by means of national actors, cross boarder actors, or international actors. In the search for a governing framework of the Syrian security sector within a decentralized system, independent intelligence agencies should have a clear mandate of intelligence gathering only (except for police forces and anti terrorism units that can arrest citizens) and an identified geographical jurisdiction. Local governing bodies should be constitutionally mandated to provide local security services and conduct police functions and duties locally. The assessment and identification of security threats and risks and the counter strategy to such risks should be developed locally and shared with central agencies for coordination.

The fifth chapter highlights the dialectical relationship between decentralization and its role in local development in countries emerging from conflict. Local development is one of the most important determining factors in whether or not decentralization is adopted in these cases. While some of post-conflict countries have reached acceptable rates of economic and social development after moving to a decentralized system, others have not. This disparity may be due to factors linked to each country’s particular local development process and adopted form of decentralization. This paper emphasizes that in the context of the Syrian situation, the country has suffered from the absence of a clear developmental model for decades. This has led to major developmental imbalances at the central state level, which are most evident in the developmental disparities between Syrian governorates. The adoption of a model of administrative decentralization in Syria will help to mitigate this disparity by empower local communities to participate in the local development process.

The sixth chapter, which deals with financial decentralization, emphasizes the fact that the successful implementation of decentralized systems of government in post-conflict countries depends largely on their ability to establish regulatory frameworks for financial decentralization and mechanisms for the collection, distribution, and disbursement of financial resources at various levels of government and administration. Successful implementation also requires substantial reforms in fiscal policy in general and in spending policies in particular. This paper finds that that the model for allocating financial resources to the local administrative units out of the state budget in Syria has many flaws. It is necessary to grant administrative units greater financial independence and to define metrics for successful financial decentralization to measure whether these units are meeting developmental requirements and making effective contributions to economic and social stability in their regions.

The seventh chapter examines the reality of local administration in regime-controlled areas. It illustrates the dominance of the central government in the local administration systems in regime-controlled areas, the growing influence of the Baath party, and the increasing influence of local Iran-backed forces in the operations of some local administrative units. This paper finds that the service sector crises in the areas of local administration units are indicative of their lack of funding, dysfunctional mechanisms, and insufficient personnel, forcing them to rely on the central government to conduct their affairs. It also argues that the regime is not interested in decentralization – which runs counter to its desire to retain centralized control – but it does use decentralization politically as a bargaining chip for negotiations with the international community, particularly the Europeans. The regime also attempted to manipulate the boundaries of the electoral constituency of administrative units to change administrative districts and weaken opposition areas by preventing them from winning elections in their areas while rewarding loyalists.

The eighth chapter focuses on the reality of governance in Syrian opposition-controlled areas. It reaches several conclusions, the most important of which is that local councils have undergone changes in terms of structure, mechanisms of formation, and function, as their organizational structures have stabilized and they rely increasingly on the elections for their membership. They have also been able to consolidate their service roles, compared to their role in local security and politics. The financial file is one of the primary challenges facing local councils as they cope with growing financial deficits, due both to the nature of revenues and expenditures, and also their lack of financial systems or laws regulating their budgets. This chapter explains how the long duration of the conflict, the transformations in its nature, the push towards coexistence, and the survival of the regime have all stimulated competition between local actors, of which the local councils were one of the most prominent players due to their political value and local legitimacy. As a result of the way the local councils have dealt with these challenges and threats, they face one of three scenarios in the foreseeable future: vanishing entirely, forming regional or cross-regional self-administrations, or continuing the current independent local units structures.

The ninth chapter analyzes the reality of governance in the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. It shows that lack of transparency is a key feature of service delivery, financial administration, and the management of strategic resources within the Democratic Autonomous Administration (DAA) areas. The process of forming legislative councils (mandated to pass laws) in these areas was based on partisan consensus that relied primarily on the literature and system of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM). Laws passed by these legislative councils, such as laws related to self-defense, changes to school curricula, and civil status laws, are problematic. A review of the structure of the DAA and its legislative and executive bodies, shows the presence of a partisan political project that is being forced on the local population through its security and military apparatuses. This paper concludes that the DAA, though able to impose a unique governance model, still suffers from problems of representation, legitimacy within its population, and a lack of competent personnel, and it has failed to eliminate the local and regional concerns arising from this project.

The tenth and final chapter of this book proposes a unique Syria-customized decentralized framework, one that takes into account the importance of achieving stability. It highlights the importance of refocusing international negotiations on two parallel tracks: negotiations policies to strengthen central state institutions in order to create conditions for peace and stability, and empowering local governance models through local negotiations on power sharing of authorities and functions of the central state with local administrative units. They must also revisit the basic Geneva Communiqué according to the principle of power sharing agreements between the center and periphery and not only a central agreement where the opposition and regime share authority. This means prioritizing internationally-monitored elections over any other track, beginning with local administration elections.

In order to ensure the success of the elections, essential actions are required from the different parties with regards to the restoration of the functionality of police and local courts. It is therefore necessary to begin drafting a new law for local administration (decentralization) to allow locally-elected authorities to have full control over the work of the police and administration of local courts.

The opportunity exists for local councils to legitimize their structures and negotiate new authorities, guaranteeing a decentralized model that provides expanded authorities to the councils and governorates, based on the strength of their electoral legitimacy. This chapter emphasizes the need to empower the tools and foundations of local governance both constitutionally and legally, and to ensure that the countries with a presence on Syrian soil help push the negotiations to a peace-building stage and guarantee relative stability on the ground until an agreement on the various security arrangements is concluded.

for More Click Here: http://bit.ly/2B2Vxqd

Navvar Saban "Oliver": "There is no final agreement and no final disagreement"

Navvar Saban "Oliver", the Information Unit manager at Omran Center, recent interview entitled "Battle for Syria's last major rebel bastion on hold as Putin and Erdogan meet to discuss next moves" by Borzou Daragahi, published in the Independent

“There are 12 observation points were equipped with limited military equipment and their main role was to monitor the agreement done in Astana. at the moment when the regime started to mobilise its forces around Idlib, Turkey started to send reinforcements to some of these points.”

he also added the follwing , for the second week in a row, thousands of Syrians in the province took to the streets in peaceful, colourful demonstrations that recalled the first months of the 2011 uprising against the Assad family’s decades-long dictatorship. “For the time being, everything is postponed,” at the end he said. (There is no final agreement and no final disagreement.)

Independen: thttps://goo.gl/QxMjgt

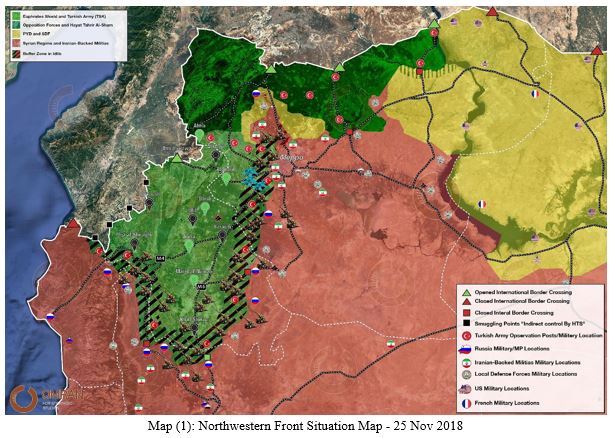

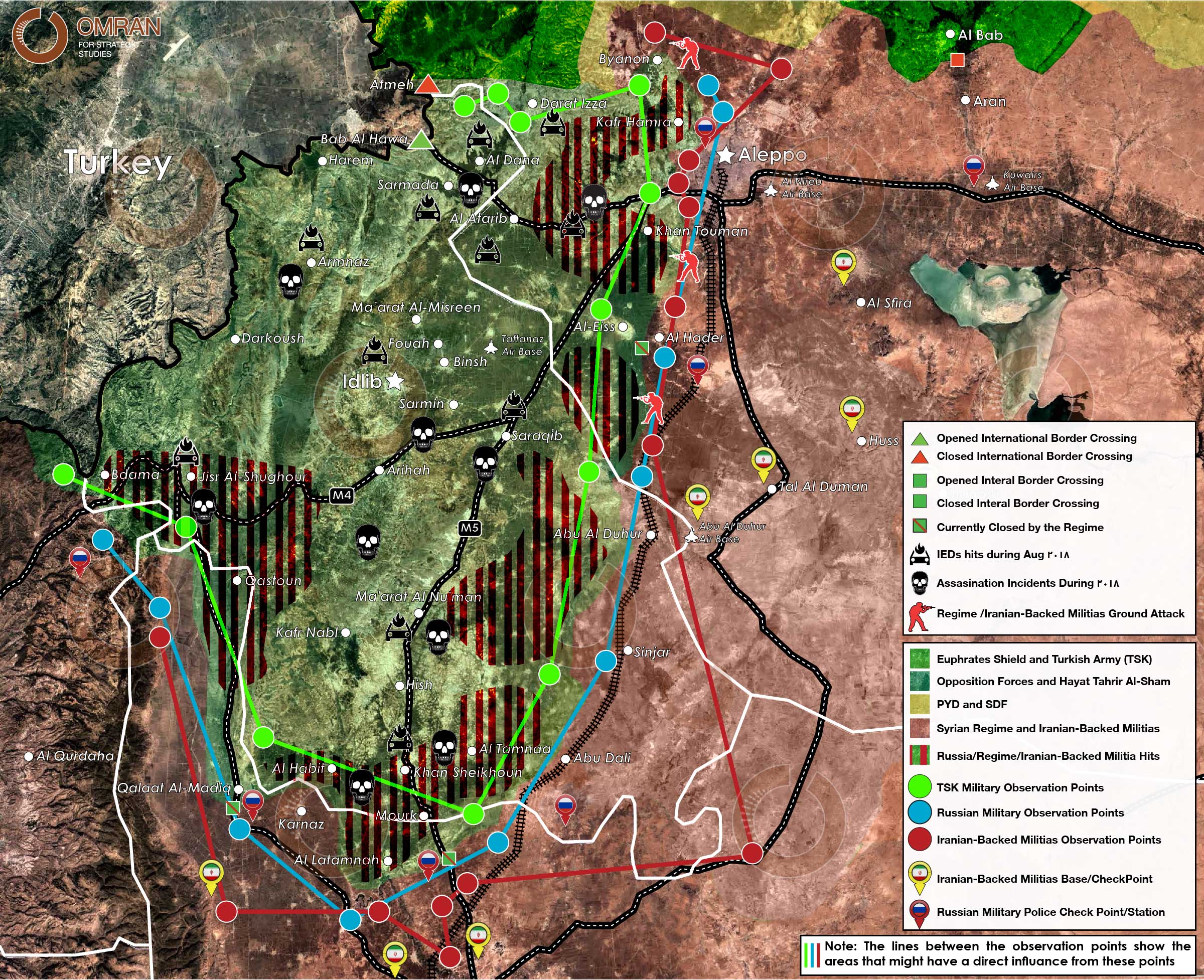

Area of influence Map of Idlib and its surroundings

Map 1: Updated situation map of Idlib, western Aleppo and northern Hama

- Iranian-backed militias’ military bases.

- Russian military police checkpoints around Idlib province.

- International Highways crossing Idlib province (M4 and M5).

- International border crossings with their current operating status and internal border crossings with their current operating status.

- Areas targeted by regime forces, Russian air force, and Iranian-backed militias’ artillery in August 2018.

- Sites of IEDs and assassination incidents that occurred in Idlib and western Aleppo Province in August 2018.

Notes:

- M4 and M5 highways are considered one of the main strategic targets for any possible attacks from the Regime and his Iranian allies.

- Internal border crossings are trading hubs between areas under regime control and areas under opposition control. Currently these borders are closed by the regime for different reasons, except "Qalat Al-Madiq" in Sahel Al-Ghab was partially opened in the last few days to allow the last IDPs convoy from the south to enter Idlib.

- On 13 August, Russian Military Police took over both "Qalat Al-Madiq and Mourek" corresponding internal border crossing sites in regime areas replacing the Syrian Army’s 4th Division (Affiliated with Iran).