Omran Center

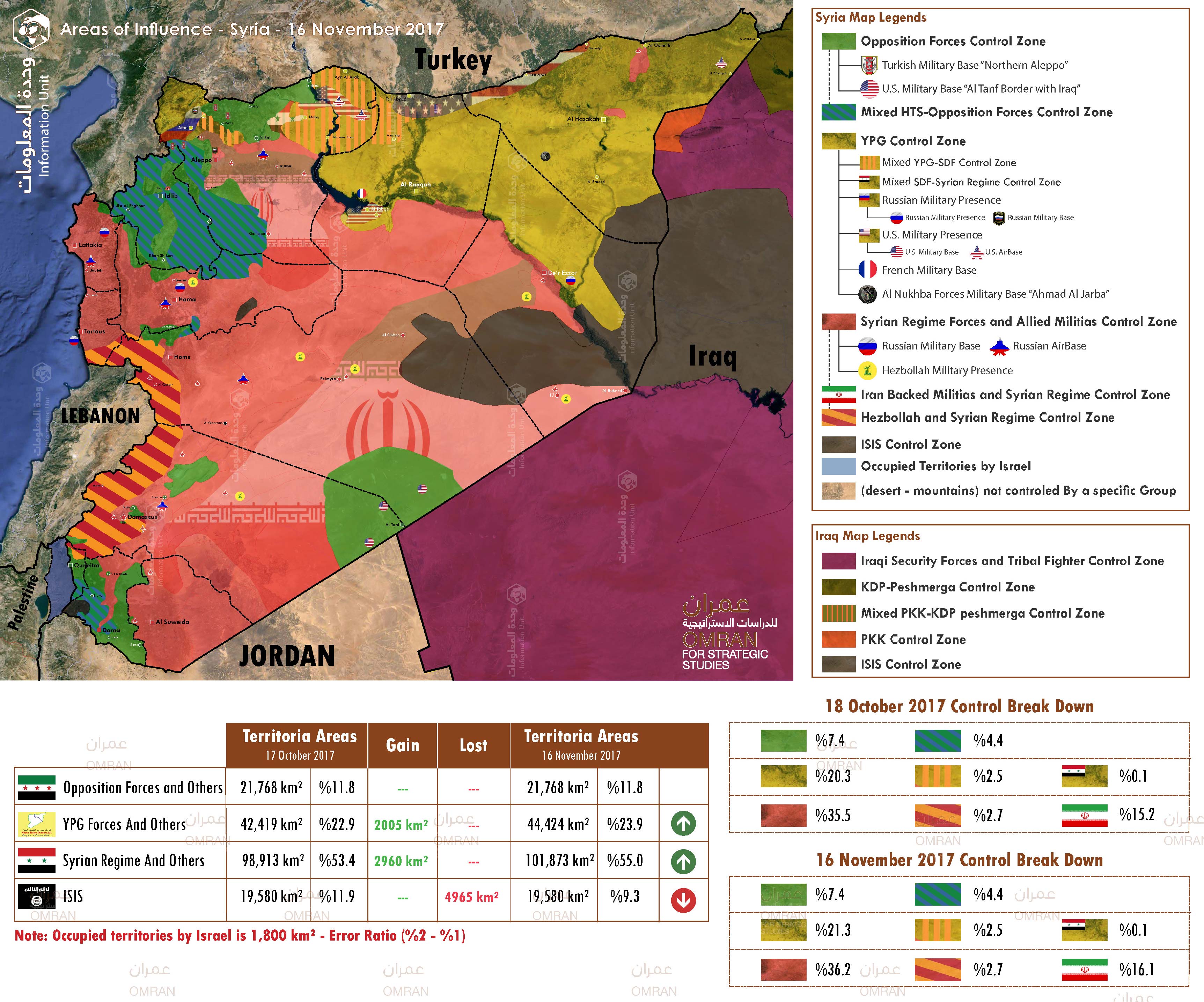

Map of Control and Influence: Syria "16 November 2017"

Damascus

- November 11, unconfirmed reports indicated that Jaish Al-Islam and the Government of Russia reached an agreement stipulating Jaish Al-Islam’s future role as the sole military and political actor in Eastern Ghouta.

- November 12, a UN inter-agency convoy entered Duma city, Duma subdistrict, through Al-Wafideen crossing in coordination with SARC and the ICRC.

- November 15, Ahrar al-Sham launched an attack on the regime forces stationed in the management of vehicles in Harasta, the attack came in response to the regime's repeated attacks on Eastern Ghouta.

Important Note:The humanitarian situation in Eastern Ghouta continues to deteriorate. Bread pack prices reached 1,900 SP, 1kg of rice is currently at 4,000 SP, and most day-to-day essentials are scarce in public markets.

Southern Front

- November 12, Unconfirmed reports suggest the Jordan-based Military Operation Center (MOC) has disbursed its last payment to Southern Front Alliance combatants, as well as its final arms and munitions delivery.

Al Hasakeh

- November 9, SDF established full control over Markada city, in Markada subdistrict, Al Hasakeh governorate.

Important NoteMarkada was considered as the last major city controlled by ISIS in the governorate. Moreover, SDF control over Markada secures its control over the eastern bank of Euphrates River in southern Deir Ez Zor, as well as oil and gas in the area. Nevertheless, reprisal attacks by ISIS combatants remain possible.

- November 12, YPG-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) reportedly handed 52 Russian Chechen individuals, thought to be families of ISIS combatants, to the Government of Russia.

Aleppo

- November 12, Clashes and shelling continued in western rural Aleppo governorate between Noureddine Zinki, a prominent armed group in northern Idlib and northwestern Aleppo, and Hayat Tahrir Al Sham (HTS).

Important Note Clashes reportedly ensued after Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham attempted to prevent combatants who defected from Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham from joining Noureddine Zinki in Hayyan and Andan, in Haritan subdistrict, which is controlled by both groups. During the clashes.

- November 13, Syria Regime and aligned forces, allegedly to include Russia, carried out airstrikes on Atareb city, Atareb subdistrict in northwestern Aleppo governorate. Various media sources and local sources have reported casualties at approximately 70 individuals, while several sources reported that at least one airstrike targeted a market in central Atareb city as well as a police station.

Deir Ez Zor/Al Raqqa

- November 8, Syria Regime and Pro-Iran Militias reportedly took control of the Abukamal border crossing, located on the Syria-Iraq border in southeastern Deir Ez Zor governorate.

Important Note as of November 5, Hashd Sha’bi, an Iraqi Hashd Sha’bi militia, took control over Al-Qaim town and its nearby border crossing, opposite Abukamal along the Iraqi-Syria border.

- November 11, SDF reportedly controlled Basira, in Basira subdistrict, and its vicinity, located approximately 32 km south of Deir Ez Zor city.

Important Note 69,047 individuals have been displaced from Abukamal subdistrict to SDF-controlled areas in northern and eastern Syria due to clashes between Syrian Regime forces and ISIS.

Internship Opportunities at Omran

Available fields for Interns

- Research Assistantship.

- Data Monitoring, collection, and analysis.

- Translation and copy editing of research / reports between English-Arabic-Turkish.

- Marketing, Graphic design and Multimedia Production.

Requirements

- Senior Students or graduates in humanities fields of political science, economics, sociology, public policy and governance, translation, or other related humanities fields with focus on Syria and the region.

- Should be able to read and write fluently in English. Knowledge of Arabic or Turkish is a preference.

- Should provide a statement of purpose outlining his/her research interests and the field they would like to work with at Omran.

For Specific Inquiries on the Omran Internship Program, send your resume and research interests to: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

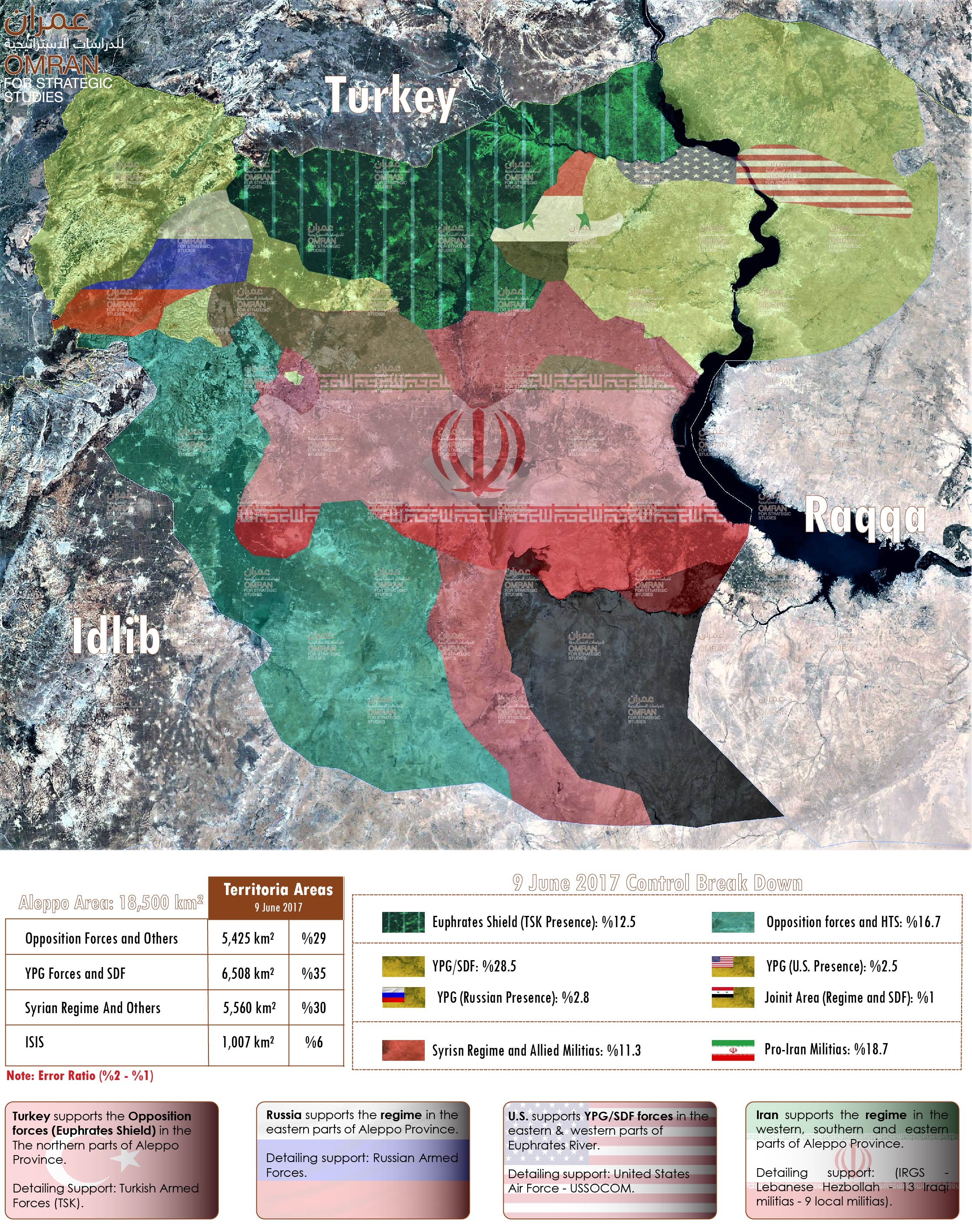

Map of Control and Influence: Aleppo Province "9 June 2017"

Battle of Deir ez-Zor & Raqqah September & October 2017

- October 9, Syrian Democratic Forces reportedly continued their advance in the eastern Deir-Ez-Zor governorate, capturing Mweileh town in Sur subdistrict, located north of Sur city.

- October 10, Syrian Regime offensive is largely dependent on Russian aerial coverage; the Russian Foreign Ministry announced that 150 daily Russian airstrikes had targeted ISIS bases in Mayadin city.

- October 15, SDF spokesperson announced that all willing combatants have evacuated the city; however, the likely destination of potential ISIS-affiliated evacuees is currently unknown. Furthermore, the SDF-led ‘Wrath of Euphrates’ operation against ISIS has led to SDF control over most neighborhoods in Ar-Raqqa city amidst heavy aerial support by the U.S.-led coalition, resulting in a high rate of civilian displacement.

- October 15, Syrian Regime forces and Allied Militias, supported by Russian aerial and ground forces, continued their advance south of Deir-Ez-Zor city, Syrian Regime forces, advanced into Al Mayadin city, Al Mayadin subdistrict, located 43.8 km south of Deir-Ez-Zor city.

- October 17, About 400 Islamic State (ISIS) members, including foreign fighters, have in recent weeks surrendered to U.S. backed forces in ISIS former Syrian stronghold Raqqa; inside source confirmed that the ISIS Syrian fighters were transferred to "Ayn Issa" Camp, while the foreign fighters were transferred to "Suluk" Military headquarter.

- October 18, Syrian Democratic Forces reportedly captured the several villages from ISIS, 7 KM eastern side of Deir-Ez-Zor City.

Important Note: As of the end of September, nearly 708,000 individuals are reported to still remain in ISIS-held communities in Deir-Ez-Zor governorate. This includes approximately 120,000 individuals in ISIS-held northern Deir-Ez-Zor governorate between Tabni, Tabni subdistrict, Deir-Ez-Zor City and the Euphrates River; 68,000 individuals in the ISIS-controlled western Deir-Ez-Zor governorate from Khasham in Khasham subdistrict to Markada across Khabour River; 120,000 in southern Deir-Ez-Zor governorate from Hajin to Abukamal; and nearly 400,000 individuals in the central Deir-Ez-Zor governorate.

Workshop on Cooperation Prospects in Institutional Reform and Restoring Stability in Syria

Omran Center for Strategic Studies organized a workshop in partnership with and hosted by the Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP). The workshop discussed international cooperation prospects on institutional reforms necessary to restore stability in Syria. This workshop took place at GCSP on 21-22 September 2017.

The workshop brought together 35 experts and researchers from the US, Russia, Germany, the UK, France, Australia, Switzerland, and Syria. The participants gathered for two days to exchange views on stability in post-war Syria.

The vibrant discussions focused on the place of Syria in the West-Russia global power contest; institutional reforms within the political transition; prospects of cooperation on reconstruction; local governance; de-radicalization and counter-terrorism; and disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR).

The workshop is part of the Syria and Global Security project, jointly run by Omran and GCSP. It is an initiative to offer a platform for collective informed discussions on Syria that eventually could build bridges between experts and researchers in order to bring peace and security to Syria, and the region.

ISIS Areas of Control in Eastern Syria and Western Iraq "Nov 2017"

- October 26, SDF forces had opened fire on civilians, originally from Al-Minshiye neighborhood, who were demonstrating in the vicinity of Al Raqqa city and demanding to return to their homes.

- October 27, Syrian Regime Forces and Allied Militias advance from eastern Homs governorate (T2), currently 65 km west of Abukamal.

- October 27, YPG-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) established full control of the At-Tanak oil field, located 35 km southeast of Mayadin city, in southern rural Deir Ezzor governorate, after the withdrawal of ISIS forces from the area.

- October 29, Syrian Regime Forces and Allied Militias continued their advances into ISIS-held areas in Deir Ezzor city and took control of Al-A’rfi and Al-Ommal neighborhoods.

- October 30, Syrian Regime Forces and Allied Militias continued their advances toward Abukamal city in southern Deir Ezzor governorate, amidst heavy clashes with ISIS forces, clashes center in Quriyeh, Ashara subdistrict, located 65 km north of Abukamal city.

- October 30, ISIS combatants withdrew toward the Syrian-Iraqi border after an agreement between the SDF and local tribes, whereby ISIS will evacuate from the eastern bank of Euphrates River to Abukamal city, and hand over the control of these communities to SDF-affiliated Deir Ezzor military council and the Sha’ytat Tribe.

Important Note: The Sha’ytat Tribe is internally divided, as some are aligned with Government of Syria forces, while others are aligned with the SDF.

- October 31, Al Raqqa city remains inaccessible to humanitarian actors due to the significant presence of Explosive Remnants of War (ERW). The humanitarian situation in the area is reportedly extremely dire as there are no functioning bakeries or markets in the city; a serious lack of healthcare and electricity; and very little potable water due to the destruction of many of the remaining wells in the city.

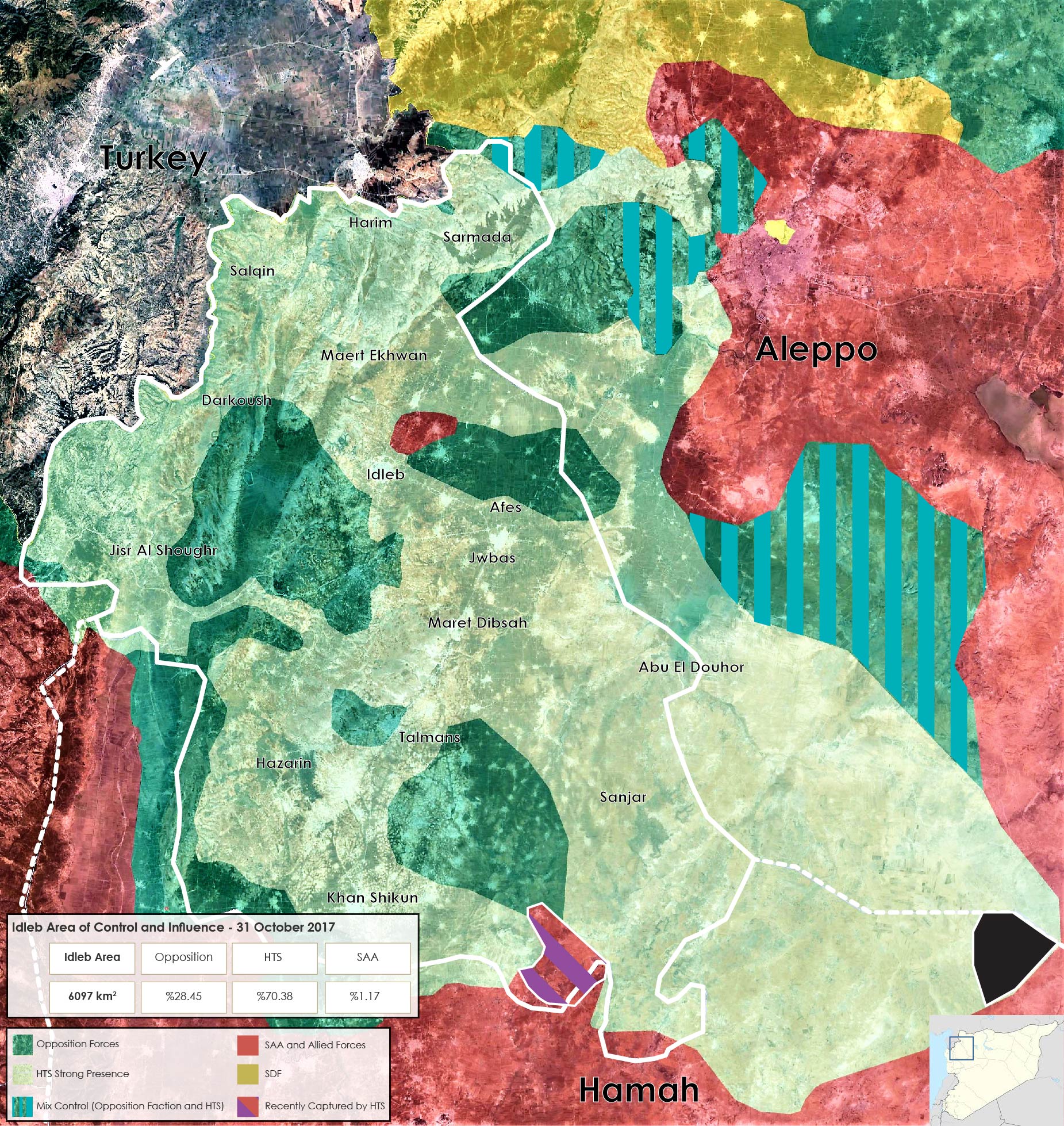

Turkey Eyeing Further Expansion in Northern Syria, Say Rebels

Turkey said last week that its campaign in Idlib was nearly complete, but recent talk over further expansion in Aleppo’s countryside signal that its operations in northern Syria may be far from over.

A map of control in northeast Syria, showing front lines between the opposition, Kurdish forces and the Syrian government. By Omran Center -Nawar Oliver

After establishing a presence in northern Idlib and western Aleppo over the past month, Turkish troops and Turkey-backed rebels are now looking to expand their area of control along the border by moving further east into Aleppo’s countryside, a rebel spokesman told Syria Deeply.

Although Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan said last week that his country’s operation in northeast Syria was nearly complete, Ankara recently dispatched reconnaissance teams to new areas, and some rebels reported being in talks to hand over their positions to Turkish forces, according to a military spokesman for the Syrian opposition faction Nour al-Din al-Zenki.

Ankara began its cross-border operation with the purported aim of enforcing a de-escalation zone in Idlib, which was agreed upon by Russia, Turkey and Iran in the Kazakh capital of Astana in September. So far, its troops have deployed only in areas separating the opposition and Kurdish forces. The Turks have not moved into front-line areas between rebels and the Syrian regime.

According to Abdul Salam Abdul Razzaq, Turkey is looking to replicate this strategy further east. He told Syria Deeply that Nour al-Din al-Zenki had already agreed to hand over its positions in rural Aleppo to Turkish forces.

He added that although it had not been determined exactly where the Turkish troops would be stationed, Ankara was looking to establish observation posts in the Sheikh Aqil Mountains, located in the al-Bab district, which Turkey liberated from the so-called Islamic State last year.

Ankara has also dispatched reconnaissance teams to Nour al-Din al-Zenki positions in the adjacent districts of al-Tamoura and Anadan, northwest of Aleppo city, but had not yet taken them over, Abdul Razzaq said. The military spokesman also cautioned the agreement could fall through if Aleppo residents objected to the Turkish presence.

It was not immediately clear what Nour al-Din al-Zenki stands to gain from the agreement. “Turkey’s deployment in Idlib is part of the de-escalation zone agreement reached in Astana, and Zenki is a signatory to this deal,” Abdul Razzaq simply said.

When asked about the significance of these positions, Abdul Razzaq said they were a clear indicator of Turkey’s attempts to encircle the Kurdish-held region of Afrin. “If the Turkish army’s priority was ensuring de-escalation, then Ankara should have first deployed on the front lines between the opposition and the regime, instead of on the front lines with Kurdish separationists,” he said. “Everyone knows that Kurdish forces are Ankara’s greatest concern when it comes to its southern borders.”

Speaking to his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) last month, Erdogan said that although Turkey’s Idlib operation was nearly complete, “the Afrin issue is ahead of us … We can come suddenly at night. We can suddenly hit at night.”

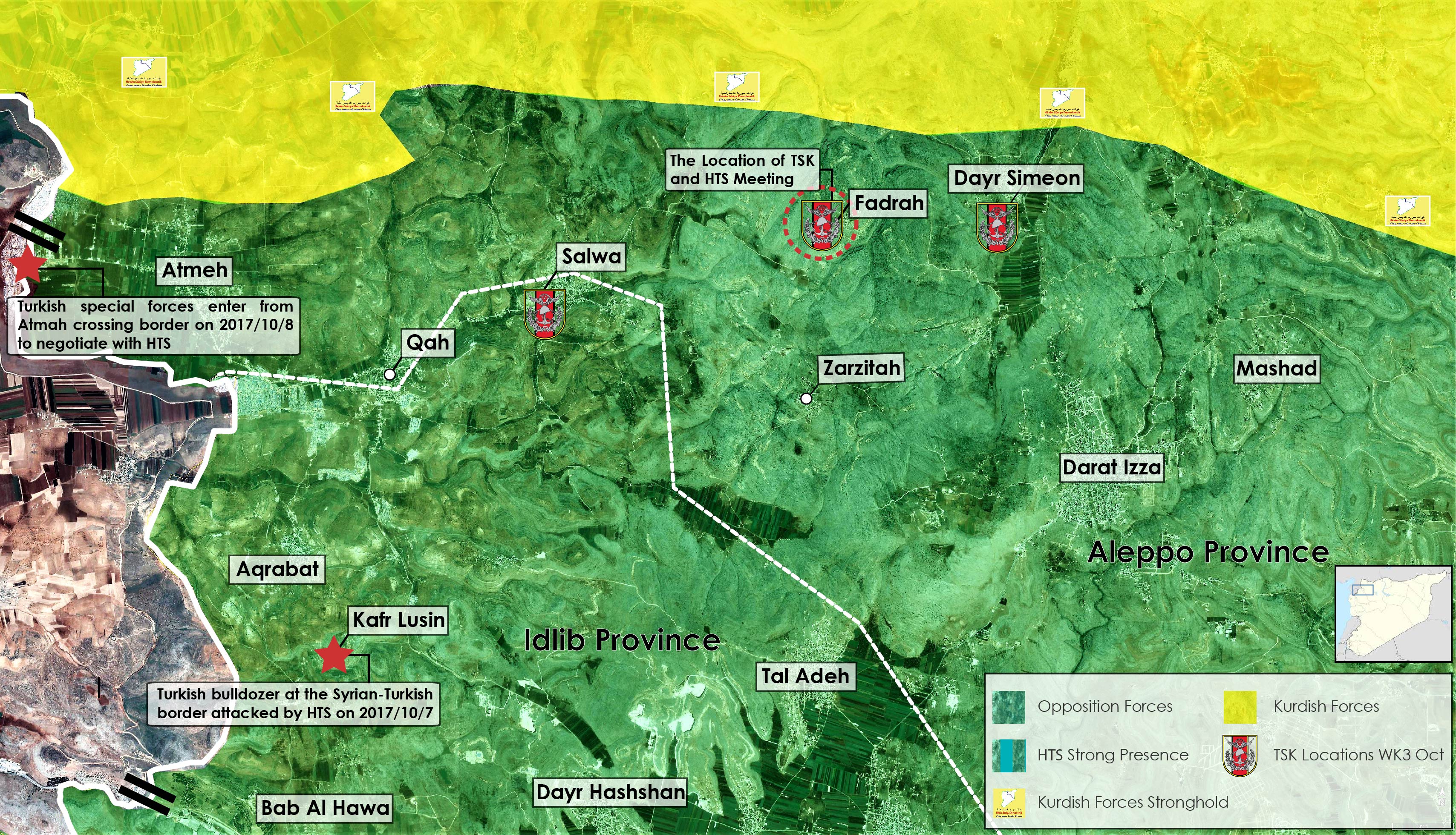

Turkish Deployment in Northeast Syria

A map showing Turkish positions in Idlib province as well as front lines between Turkish forces and Kurdish groups based in the adjacent Kurdish-held region of Afrin. By Omran Center-(Nawar Oliver)

Turkey’s planned expansion comes after weeks of operations in northern Idlib and western Aleppo that have resulted in the establishment of at least three Turkish posts in areas adjacent to the Kurdish-held region of Afrin.

Omar Khattab, a military spokesman for the Turkey-backed Ahrar al-Sham rebel group, said that Turkish deployment in Idlib has been carried out in coordination with the al-Qaida-linked Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham alliance, which withdrew from areas of Turkish operations.

Charles Lister, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute, told Syria Deeply last month that HTS agreed to surrender positions to the Turkish army to prevent a costly all-out war with Turkish troops.

Ahrar al-Sham’s military spokesman said he was not authorized to disclose the exact coordinates of these positions, but Ahmad Saoud of the Free Idlib Army’s Division 13 Brigade said Turkey has built a launching-pad base in the Sheikh Barakat Mountain in Dar Simeon.

The position is only a few miles from Kurdish militia forces based in Jendaris and is located roughly 7 miles (12km) from the Turkish borders. A video posted by the activist-run Smart News Agency on October 24 shows Turkish bulldozers and armored vehicles operating in the area.

Turkish troops have also dispatched forces to the village of Salwa, which is near the border of Afrin, according to Abdul Razzaq. The activist-run Thiqa News Agency has posted a video on social media networks showing Turkish armored vehicles moving in the area.

Rebel sources said that Turkish troops have also purportedly deployed in the village of Fadrah near the Sheikh Barakat Mountain.

Turkey’s operations in northern Syria are laying the groundwork for the establishment of a border buffer zone that stretches from the Atmeh border crossing as far east as Jarablus. Following the Euphrates Shield Operation last year, Turkish-backed forces gained control over the Jarablus, Azaz and al-Bab in Aleppo’s countryside. Current expansion in Anadan, Tammoura and Sheikh Aqil will help Turkey connect its positions in Northern Idlib with Euphrates Shield territory in Aleppo’s countryside.

In another indication of Ankara seeking to entrench itself along this stretch of the border, Turkey’s state-run Anadolu news agency reported last week that Turkey has reportedly trained some 5,632 Syrian volunteers to work as police officers in the area. Some volunteers have already been dispatched to the areas of al-Bab, Azaz and Jarablus, Anadolu said.

Strait Talk: Panel discussion with Yaser Tabbara and Sinan Hatahet on the latest in Raqqa

Mr. Yaser Tabbara board member of the Omran Center for Strategic Studies. And by Sinan Hatahet answered several important question in regard of Raqqah operation and what is the current condition after U.S. and their ground Allies "PYD" took control of the city from "ISIS". Mr. Yaser talked about the current relationship between the U.S. and "PYD" specially after raising "Ocalan" picture in the city by some "PYD" fighters. Mr. Yaser also talked about the Syrian Regime reaction on "PYD" taking control of the City, and what are the possible scenarios for the Regime in regard of Raqqah

Book: Changing the Security Sector in Syria

This book is a result of a 10-month long project that included a series of papers, consultations, and workshop on security sector reform. The objective of this book is to clearly identify the relevant cognitive, political, social, and technical conditions for transforming Syria’s security structures given the current situation in Syria. An executable vision in this regard should be driven by common interests of all actors, and must divert the conflict from political competition among the warring parties—local, regional, and international—allowing them to identify compatible conditions for local security in coordination with a centralized security architecture that is also in line with regional balances. The primary research questions of this book were:

1. How compatible is the Syrian political situation with the current security sector? What are the conditions in the proposed political scenarios relating to the nature of the new political system in Syria that will prevent the repetition of previous failed attempts?

2. Do the existing security structures in the various parts of Syria under the control of varied groups have the ability to deal with constantly changing security threats? Are they changeable?

3. What roles and programs are required from the community to engage and participate in the formation and maintenance of a security strategy?

4. What is the potential for security reform in Syria and the nature, level, and goals of the plan to execute such reforms?

This book is organized in three chapters.

The first chapter sets out the main concepts and policies required for a security sector transformation. It includes steps for restructuring the security sector, and disarmament and reintegration programs, while drawing on the experiences of other post-conflict countries. Additionally, it identifies the primary catalysts for security sector transformation, such as a strong civil society and transitional justice programs.

The second chapter evaluates existing security architectures in zones controlled by the opposition, regime, and Democratic Union Party (PYD) “self-administration”. This chapter further assesses the current security structures and their effectiveness and capacity to achieve their declared security goals. It also discusses centralized and decentralized operations and functions of security.

The third chapter deconstructs challenges in transforming the security structures in Syria, in order to ultimately present a practical and achievable proposal. The last part of the chapter puts forward a proposed security vision and action plan based on a set of strategic objectives that ensure a cohesive security sector that can operate effectively and allow communities to participate in their own security operations. It also provides a timeline with three phases of reform measures— the pre-transition or “peacebuilding phase”, the transition phase, and the stability phase.

Mr. Yaser Tabbara poses the question of international accountability in Syria's war

Mr. Yaser Tabbara Researcher at Omran Center for Strategic Studies, poses the question of international accountability in Syria's war, after a regime soldier has been prosecuted for a war crime. Mohammed Abdullah claimed asylum in Sweden in 2015. But activists recognized him from online photo, smiling, surrounded by dead bodies. So, instead of receiving refuge, he got an eight-month prison sentence for mistreating corpses.

Yaser Said: 8 month for something so horrific is a little bit more than a slap on the rest, but still it is significant being the first incident of international accountability for such crimes, he added that the lack of evidence are considered a major problem and a weak link for the universal jurisdiction. He answered the question of "what about the head commander committing these crimes?"; International criminal justice lacks enforceability, the Russian and Chinese have been putting the main obstacles to the international criminal court, that is purely because political reasons.

Yaser ended the interview saying that not all soldiers should be banned from asylum, it's all depend on their acts on the ground and on what they were force to do while the regime was committing his crimes, and to attain absolute justice is something most of the Syrian have given up on