Omran Center

Syrian Refugee Employment in Turkey

According to official statistics, the Turkish Republic hosts nearly 3.5 million Syrian refugees, more than any other country. A number of studies show that a vast majority of these refugees will remain in Turkey permanently, even if the situation in Syria becomes stable and return becomes a possibility. Despite this trend, however, government institutions and organizations have failed to establish a sustainable framework for integrating Syrian refugees into Turkish society. Although the Turkish government addresses some specific areas of need, many refugees must take responsibility for securing their own livelihoods. Due to a gradual decrease in international aid and the long-term presence of Syrians in Turkey, it has become more difficult for refugees to find suitable employment opportunities. Whereas issues of housing, education, health, and food are related to problems of capacity and bureaucracy, the issue of livelihoods is more closely linked to the legal framework and the perception of Syrian refugee employment among Turkish citizens. This problem is not only a humanitarian issue but a political one, both nationally and globally.

For Syrian refugees, employment is more than a job. It has a significant and sustainable impact on an individual’s life, future, and ability to integrate into a new society. Unemployment, however, is a significant problem in Turkey. Some estimates indicate that working-age people in Turkey account for more than 50 percent of the population, yet the unemployment rate exceeds 17 percent, according to the Livelihood Observatory. Moreover, in response to the influx of Syrian refugees in Turkey, an insufficient amount of funds has been allocated to livelihoods sector to enable Syrians to build their livelihoods in Turkey. According to the 2016-2017 plan of Syria's humanitarian response, the amount of funding available for the livelihoods sector was $11 million (USD), but the funding requirement was $92 million (USD). As a result, the Turkish government has faced significant challenges, creating employment opportunities for Syrian refugees, integrating and organizing refugees in the labor market, and addressing problems between refugees and their employers.

There are a number of obstacles that prevent Syrian refugees from developing their livelihoods. Most notably, legal procedures related to the employment of Syrian refugees lack clarity and integrity. In addition, there is poor communication between Syrian civil society organizations and the Turkish government, as well as a lack of representative bodies demanding employment rights for refugees.

Most Syrians live in Turkey under temporary protected status, which fails to ensure certain protections. In fact, Turkish labor laws that apply to Syrian refugees are inadequate and inefficient. Due to difficult financial conditions, refugees are vulnerable to exploitation, including unfair compensation. In addition, refugees performing physical labor at work face a higher risk of injury, yet some employers do not provide them with health or social insurance.

To overcome existing obstacles, all actors in the livelihoods sector should collaborate to create appropriate mechanisms that enable Syrian refugees to secure jobs and develop their livelihoods. Specifically, the Turkish government should create a database, accessible to all relevant parties, for Syrian employment opportunities and establish appropriate mechanisms to assess the qualifications of Syrian refugees. In addition, the government should implement vocational training programs for secured employment and establish a union for Syrian workers under the supervision of the Turkish Workers Syndicate. The government also should support Syrian refugee recruitment agencies and provide them with necessary funding and facilities. To support small business and micro-enterprisesfor Syrian refugees, government agencies should provide appropriate facilities. They also should facilitate banking and investment procedures for Syrians to expand their ventures and create new jobs, and they should utilize the financial resources and expertise of Syrians abroad in order to develop Syrian livelihoods in Turkey. In addition, the government should establish joint large-scale industrial projects connecting Syrian and Turkish investors.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) should identify and develop mechanisms to sustain livelihood programs and ensure their growth. They should establish a cooperative fund to provide small grants to entrepreneurs, and they should conduct community awareness and education campaigns to inform Syrian refugees about their rights and responsibilities in the labor market. In addition, NGOs should establish programs to help at-risk refugees find employment opportunities. They also should create sustainable initiatives that enable coordination and cooperation between Syrian and Turkish employers. These programs should produce joint economic projects in all sectors and support vocational training and rehabilitation programs for Syrian refugees. In addition, these programs should ensure that Syrian refugees are not exploited due to legal status or physical condition.

With the significant and lasting presence of Syrian refugees in Turkey, temporary solutions are no longer viable, especially as more and more refugees enter the labor market. Unless concerned parties in the Turkish government work to develop sustainable solutions, refugees and their host communities will face serious problems, such as increased tension between refugees and the local population, as well as social and economic instability. On the other hand, the employment of refugees will benefit the Turkish workforce and economy, while ensuring a promising future for Syrians in Turkey.

Workshop in Geneva:"Strategies for State Building in Syria"

Omran for Strategic Studies and Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP) hosted in Geneva a workshop entitled ‘Strategies for State Building in Syria,’ for a focus on centralisation and decentralisation formulas that fit post-war Syria. The workshop is part of the Syria and Global Security Project, jointly run by the GCSP and Omran. The project aims to offer a platform for collective informed discussions on Syria that could build bridges between experts and researchers in order to bring peace and security to Syria and the region.

The workshop brought together 21 experts and researchers from Germany, Norway, Russia, Syria, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States. The participants gathered for two days on 1-2 February, 2018 to exchange views on potential trajectories of state building in Syria. The workshop discussed the geo-strategic context for political reform, as well as, political, administrative, financial and security aspects of centralisation and decentralisation.

For more details, a report on the workshop is planned to be published soon on this website.

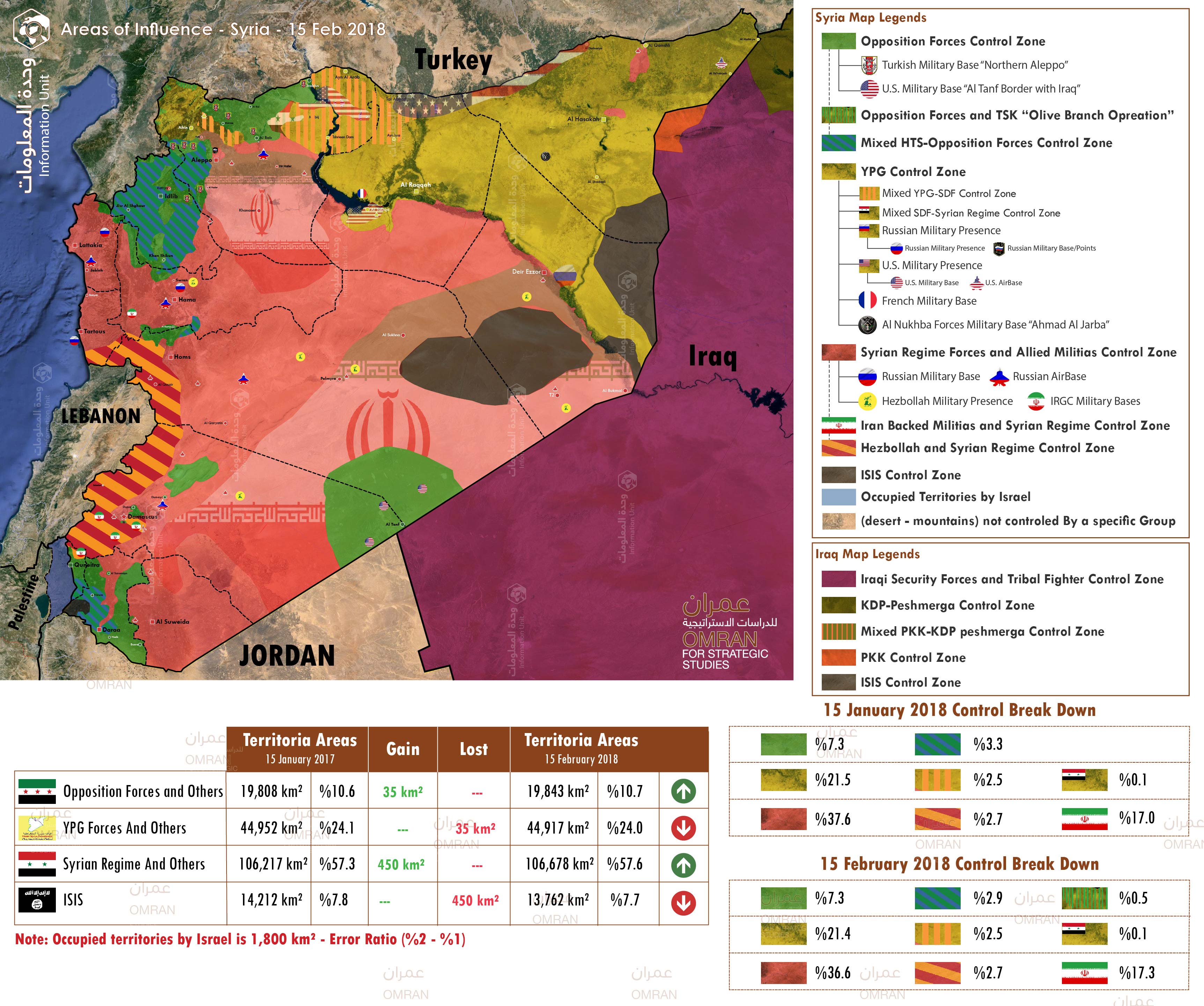

Map of Control and Influence in Syria February 16, 2018

Map of Control and Influence in Syria:

- Turkish Armed Forces (TAF) and the Free Syrian Army (FSA) captured several locations in the western region of Afrin from the YPG/YPJ. Separately, reports emerged claiming that the TAF and the FSA had deployed additional troops and equipment west of the Jandaris district indicating an upcoming offensive.

Pro-YPG sources said that Kurdish forces had repelled Turkish attacks in the districts of Rajo and Bulbul, and claimed that more than 20 Turkish-backed fighters were reportedly killed there.

February 5: A massive Kurdish military convoy entered the Afrin region to support the YPG in its fight against the Turks. As a result, many issues were raised:

- The number of vehicles that left Manbij was 36, but 41 entered Afrin, meaning five extra vehicles joined the convoy from areas controlled by pro-Iran forces.

- After the convoy entered Afrin from a checkpoint in Nubl and Zahraa, areas controlled by pro-Iran forces, multiple Iranian weapons were spotted in the possession of Kurdish forces. Below is a full list of these weapons.

2. Syrian regime and pro-Iran forces, as well as US-backed forces, are reportedly amassing troops and fortifying their positions in the Euphrates region. According to both pro-opposition and pro-government sources, the two sides are preparing for possible skirmishes in the area.

3. February 10: Israeli airstrikes destroyed nearly half of the Syrian regime’s air defenses, according to the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, which cited “senior Israeli Defense Forces officials” in the article on February 14. An Israeli F-16 was shot down during the airstrike; however, Israeli officials considered the operation a success.

February 12: AnIsraeli military official said that an Iranian drone shot down 10 February 2018, ago was based on a US stealth RQ-170 UAV, which was captured by Iran in 2011. Iran started production of this drone in 2016.

Meeting entitled “Local Councils and Security Sector Reform in Syria”

The representatives of various public institutions and diplomats serving in the Embassies in Ankara attended the meeting as well as OMRAN and ORSAM representatives. Two reports prepared by OMRAN Center experts with respect to the local councils and security sector in Syria were presented at the meeting.

Workshop entitled: Syrian military & political trajectories in 2018

Omran Center for Strategic Studies held a special briefing at its new office in Washington, DC, on Thursday, January 25. Dr. Sinan Hatahet, a research fellow at Omran Center, and Dr. Ammar Kahf, executive director of Omran Center, each delivered a presentation on Syrian military and political trajectories in 2018. They discussed patterns of local governance and the influence of domestic actors and cross-border groups in Syria.

This presentation marks the official launch of Omran DC, which will serve as a companion of its headquarters in Istanbul. Through its publications and workshops, Omran DC seeks to inform sustainable solutions to existing challenges, concerning security and military reform, local governance and administration, Iranian and international influence in Syria, and national political issues. Omran DC is a Partner in Residence with New America, a think tank dedicated to a range of public policy issues.

Military and Security Structures of the Autonomous Administration in Syria

Executive Summary

The military bodies that are part of the Autonomous Administration in northeastern Syria receive their inspiration from a number of factors related to the political leanings of the parties that control the region. Thus, the group extracts its legitimacy, not from local demands for its presence, but instead from the urge to achieve certain political ends, including local empowerment and establishment. There are two main references for the group’s project. First, the project references the political ideals of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and Tev-Dem, formerly known as Rojava KCK, which contributed to the formation of the military units there. Second, it references the direct connection of the military units to the administrative, legal, and executive bodies of the Autonomous Administration.

- The organization into a united structure of the military groups loyal to the PYD happened during two time periods. First in 2004, small groups were formed after the protest movement at the time. These groups were formed in villages and did not form into any official military group as part of the PYD untilthe recent Syrian revolution. The majority of the party’s military activities were directly aligned with the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK), especially on issues like recruitment. The second time period is best identified by the organization of military forces into a united force, known as the Syrian Youth Movement, which was led by Khabat Derik.

- Military control over the armed forces of the Autonomous Administration is due to a combination of internal factors, including a joint effort between the Assad regime and the Autonomous Administration to establish stability, as well as support from outside actors, such as the international coalition. These factors did not result in a degradation of the group’s autonomy.

- The YPG and YPJ are the backbone of the military forces in the Autonomous Administration. They depend upon the PKK for their training and military planning. Their force is estimated to comprise between 20,000 and 30,000 fighters. To maintain military hierarchy and organizational structure, they depend on the experiences and advice of the PKK. The YPG also created two academies, one for men and women respectively. The academy for women is called “Martyr Sheelan Academy.”

- The Autonomous Administration started its reform and restructuring of its military units at the beginning of 2017. This was done in coordination with the international coalition and with American support for the Syrian Democratic Forces. The YPG, along with the SDF, also managed to take control of expansive, another factor that resulted in the need for restructuring. The structure they chose to implement is not much different than the YPG’s existing structure, since it is based on their internal bylaws. The YPG does not give accurate public information about its true numbers, but the group has suggested that it comprises approximately 50,000 fighters.

- The HPX is another main fighting force in the Autonomous Administration. This group is composed of citizens who are required to join through the forced conscription program. The Self-defense Council spearheaded these efforts after the Self-Defense and Protection Council provided confirmation through a social contract signed on January 21, 2014. The council’s bylaws were adopted by the legislative council on July 13, 2014.

- The military forces created this structure to “build a well-trained and disciplined military force that would form into an army with official recognition and organized with a clear hierarchy,” according to Rizan Kilu, a co-president of the Self-Defense and Protection Committee in Jazira.

- In Jazira Canton, there were 29 training courses offered between November 20, 2014 and July 21, 2017. In the Ain Arab Canton there were 8 training courses offered between June 6, 2016 and October 10, 2017. In the Afrin canton there were 10 training courses offered between July 5, 2015 and June 5, 2017.

- After the training program, the Self-Defense Council depends on the conscripted fighters to provide various services, offer logistical support to the YPG, and construct or renovate military academies and buildings.

- The Self-Defense Council in Afrin trains special forces at a higher rate than other cantons. These special forces are recruited and trained from among the conscripted locals. Three groups of special forces in Afrin have graduated as of the date of publication of this report.

- At age 18, males are required to serve a minimum amount of time and are not excused, unless they have special permission or they reach the age of 40. Women are allowed to volunteer.

- The Military Discipline Units of the Self-Defense Council are the military police. They pursue defectors and others who have failed to report for service. They also carry out some court orders alongside the conscription office.

- There are also a number of foreign groups that fight alongside the YPG. One such group is the International Freedom Battalion, formed in Ras Al Ayn on June 10, 2015. The members come from a number of countries and ideologies, including Turkish leftists (MLKP) and the Liberation Army of the Workers and Peasants of Turkey (TIKKO). There are also members of leftist movements from Europe that formed the Bob Crow Brigade and the Henri Krasucki Brigade.

- Some of the Christian forces in Hasakah province are allied with the YPG. Their military alliances are determined according to three main factors, 1) ethnic identity, including Christian Arabs and those with an independent Christian nationality; 2) the ethnic differences between the Assyrians, Syriac, and Armenian Christians; and 3) the different Christian dogmas and their affiliations with different churches.

- The Asayish were formed as a central security force when the People’s Council of West Kurdistan (MGRK) took over cities populated by Kurds in the area. They started their official operations after the regime pulled out of Ayn al Arab (later named Kobani), Rmeilan, Malkiye, and Deirik. Once organized, the Asayish announced their intention to submit to the power of the Kurdish Supreme Committee (DBK), comprised of the Kurdish National Council (ENKS) and the MGRK. They now consider themselves to be a part of the Syrian Democratic Council (MSD) and the Autonomous Administration’s legislative wing. They oversee a number of forces, including the local traffic police, the counter terror forces (HAT), the Women’s Asayish, security checkpoints, general security, and anti-organized crime operations.

- The Hêzên Antî Teror Asayîşa Rojavayê Kurdistanê (

- The Women’s Asayish first convened on October 26, 2016 with 500 volunteers in Ain al Arab in Jazira canton.

- The Civilians' Defense Forces, or HPC, was named for the Autonomous Administration’s role within the “core of society.” The HPC is responsible for protecting local neighborhoods and the committees that operate in the cantons. The group has its own checkpoints and actively investigates any possible threats in the cantons.

- The Roj Mine Control Organization (RMCO), which coordinates with the demining units in the Asayish, is responsible for disarming all mines, especially in the rural areas where there have been—or still are—active battlefronts. Since 2014, RMCO has cleared 51 square kilometers and destroyed 8,704 mines.

- Not only are the aforementioned military structures the backbone of the Autonomous Administration, but the alliances that the YPG made with foreign and regional powers also contribute to the effectiveness of the military structure. With the YPG as the main force in the alliance, and with the group’s growing importance, the focus quickly shifted to the fight against terror. This fact was confirmed when the International Coalition to fight ISIS in Iraq and Syria designated the YPG as its military partner, leading ground operations.

- At the establishment of the SDF, the groups present included the YPG, YPJ, Sotooro, Jaysh al Thuwar, Syriac Military Council, Sanadeed Army, Raqqa Revolutionary Front, Northern Sun Brigades, Jazeera Brigades, Freedom Brigade, and the 99th Infantry Brigade. After its formation, a number of other groups joined the SDF. These groups included the Free Officers Gathering (Hussam Awak), Manbij Military Council (Manbij Revolutionaries, Jund Al Haramayn Brigade, Euphrates Brigades Gathering, Al Qusay Brigade, Turkmen of Manbij Brigade, and Northern Sun Brigades), and the Army of Tribes. There are special forces allied with the SDF, but they are not officially part of the group.

- The formation of the SDF came two weeks after the Russian intervention in September 2015. On October 12, 2015, two days after the SDF’s formation, the spokesperson for the US Secretary of Defense announced that an American C17 landed in Hasaka province to deliver more than 100 containers of military supplies.

- According to unofficial sources, the American weapons delivery was organized by Lahor Sheikh Jinki, the nephew of the late Jalal Talabani.

- At the same time as the SDF’s formation, the YPG was expanding its control of majority-Arab territories in rural Hassaka, Raqqa, and Afrin. Only 11 days earlier, the Americans announced the termination a program to train and equip Syrians due to a decision to call back some troops from foreign training missions.

- American support for the SDF is a main factor contributing to the group’s strength and capacity. The US provides air support, protects YPG forces from attacks, and sends experts, advisers, marines, and other American troops to SDF territories.

- These trends were supported by the continued leadership of the coalition, which offered increased armed support to Syria's Democratic Forces and the YPG through the construction of a five or six military bases in the countryside of Hasaka, Aleppo, and Raqqa. The US provides three main types of support for the SDF—arms, military bases, and protection from enemy advances.

- The SDF consulted more than 500 foreign advisers, primarily from the US, France, and the UK to a lesser extent. These advisers helped train the SDF and YPG.

- There are approximately five to six moving and permanent American military bases in northern Syria.

- The SDF does not publicize accurate information about its numbers. Instead, Omran’s research team depends on public statements, which provide hints that uncover more accurate information. Often, SDF commanders speak to friendly local media and exaggerate the group’s true numbers. Rough estimates suggest that the group comprises 60,000 to 75,000 fighters.

- On January 1, 2016, the SDF began recruiting fighters by accepting volunteers, offering monetary compensation, and forcing others to join through conscription. The group has trained and graduated 12 groups since February 16, 2017. The graduates were from Shadadi, Raqqa, and Deir Ezzor.

- After the formation of the SDF, new fighters directly joined the military structure, instead of joining groups that operated under the SDF banner. The SDF leadership even used force to stop people from joining such groups, as was the case with the special forces of the Tayyar Al Ghad. It is notable that the Christian Forces and the Sanadeed Army are not held to the same standard.

- The SDF structure includes the following components: the Military Council (which includes leaders from all member groups), the SDF General Commander, the General Command of the SDF (led by the General Commander and 9 to 13 members, depending on need), and the Military Discipline Committee. Unlike the YPG, the SDF did not form separate military units, except for the Jaheesh Tribe, which formed a special force of 200 tribesmen independent of the SDF.

- The SDF has not completely integrated of all their forces, for the same reasons that the Syrian opposition groups have failed to do so for six years. The groups that have joined the SDF have, in fact, not separated completely from their original structures.

- The SDF was created from a mixed alliance of groups including tribes, as well as groups that were not tribal in nature but had formed in Raqqa and rural northern Aleppo. There are also some religious groups, like Christian forces, and others built upon nationalistic visions.

- There are major differences between the main force of the SDF and the YPG, and they continue to face difficulties due to this reality. Currently, there is not active armed conflict between the YPG and other groups that are part of the SDF, but some of the problems are rooted in previous conflicts. For example, there was a conflict between the YPG and the Sanadeed Army. During the Raqqa operations there were also tensions between the YPG and the special forces controlled by the Tomorrow Movement.

- The Raqqa Revolutionaries Front is considered to be one of the oldest allies of the YPG. The group had a central role in taking control of Raqqa from the regime in March 2013.

- The SDF alliance is problematic and will continue to negatively impact local and regional developments, despite the rationale for the SDF’s, its military and security structures, and its alliance with the YPG.

To Read More Click Here

Territorial Control Map - Qunitra - 21 Dec. 2017

Iran has continued its attempts to expand in southern Syria despite international agreements aimed at curbing its role in the area. Russian and American the influential countries in southern Syria consider the arrival of Iranian militias to the Jordanian-Syrian border and the border of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights to be “a red line,” which has necessitated direct interventions. Despite this, Iran has continued its expansion as part of the encirclement, which it has pursued in recent months.

Quneitra Front and Western Ghouta Battle Timeline (November – December)

- November 3, Regime Forces and Hezbollah repelled a large attack of HTS, in "Hadr" city in the northern side of the Golan Heights.

- 17 November, Israeli tank attacks Hezbollah “Qars Nafal” position between "Hadr" & "Ain Teenah" position, in the western side of Quneitra.

- 23 November, Hezbollah takes control of South "Beit Tima" after taking control of "Halef shor" and "Tell Al Teen."

- 30 November, Hezbollah and Regime forces established full control over the strategic hills of "Taloul Barda’yah" near the occupied Golan Heights.

- 10 December, Hezbollah and Regime forces have secured their recent gains in the Beit Jinn pocket in southern Syria.

- 13 December, According to pro-regime Medias, Regime forces, and allies will continue their operations in the area until they liberate the entire pocket or local militants accept a withdrawal agreement to Idlib.

- 17 December, Members (HTS) have reportedly started withdrawing from the village of "Maghr Al Meer" to the town of "Beit Jinn" in southern Syria.

- 19 December, According to pro-regime sources, Regime Forces, and Allies reached the eastern entrance to the village of "Maghar Al Meer." However, they were not able to enter the village because they failed to capture the nearby height – Tal Marwan (Marwan Hill).

Brigade 313 "IRGC New Military Formation"

In November 2017, Daraa province has witnessed surprising competition between Iran and Regime forces around the conscription of Syrian young men from the province, as well as the formation of a new force, Brigade 313, which is under the authority of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.

Despite the Iranian-led brigade only being around for a number of months, it has attracted more than 200 young men; members who were conscripted for the formation were young men from Daraa who were known to work on behalf of the regime, who were currently promoting the force based on its benefits, and the salary, which its members received.

Enlistment takes place at the Brigade 313 headquarters in the city of Sa'Sa', and new members receive an ID, which has the logo of the Revolutionary Guard, ensuring his ability to pass through Regime forces checkpoints.

Why Reports of ISIS’ Demise Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

During the same week the U.S. and Russia declared victory over ISIS in Syria, the militant group launched a series of surprise attacks around the country. Despite the triumphant claims of world leaders, these offensives suggest such statements are a little premature.

The same day that President Vladimir Putin declared victory over the so-called Islamic State, the militant group launched a surprise offensive against government forces in Deir Ezzor province, killing up to 31 pro-government fighters in the following three days.

“In just over two years, Russia’s armed forces and the Syrian army have defeated the most battle-hardened group of international terrorists,” Putin told Russian forces on Monday during a visit to Russia’s Hmeimim air base in Syria, before ISIS attacked government positions north of the town of Boukamal, a former key stronghold for the militants.

U.S. President Donald Trump made similar victory claims on Tuesday while signing the National Defense Authorization Act into law. The bill, he said, “authorizes funding for our continued campaign to obliterate ISIS. We’ve won in Syria … but they [ISIS] spread to other areas and we’re getting them as fast as they spread.”

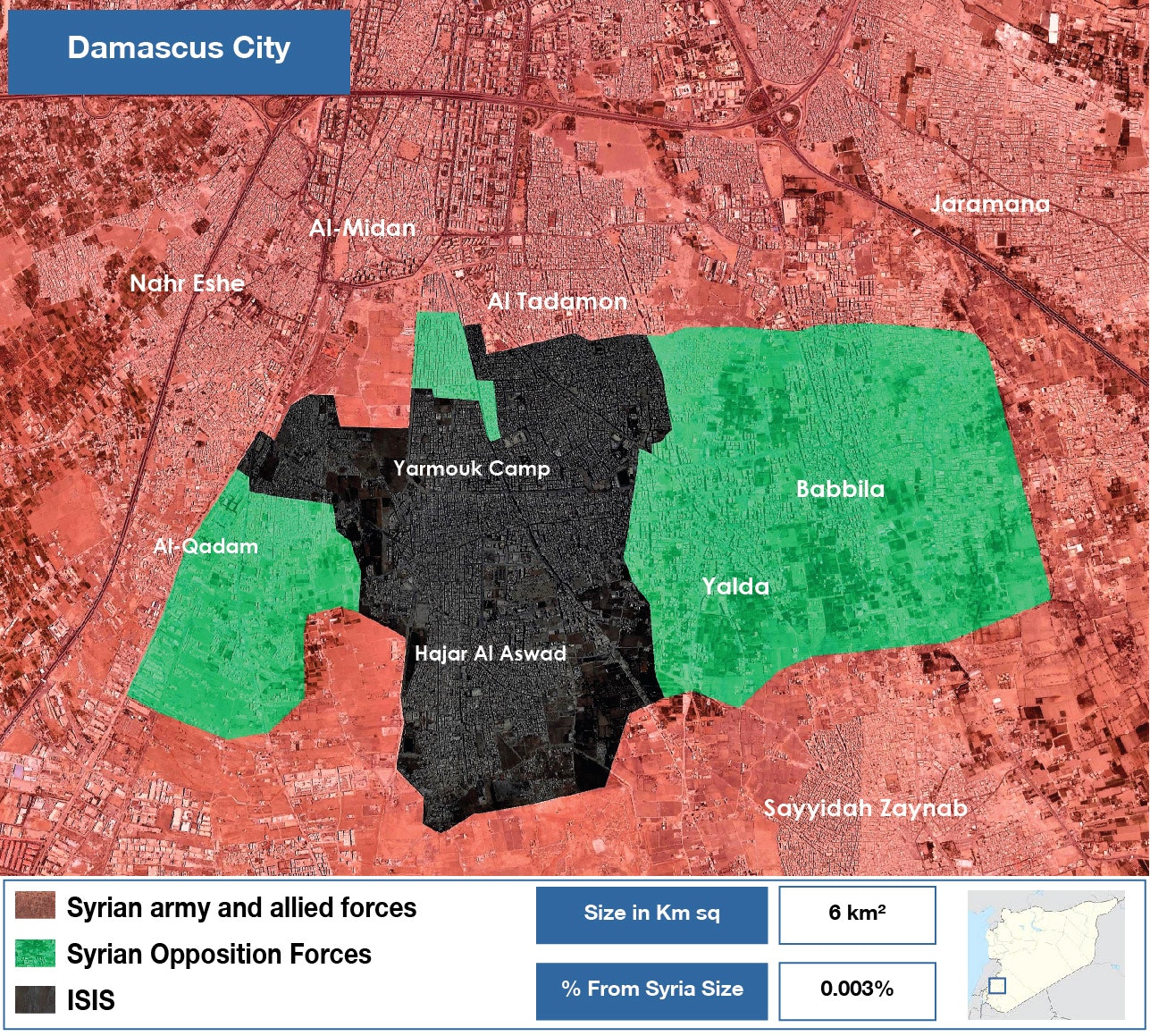

The following day, however, ISIS militants engaged in clashes with a Pentagon-backed rebel group near a U.S. base in al-Tanf in southwest Syria. Militants near the Palestinian Yarmouk camp south of Damascus also launched an attack on government positions in the nearby al-Tadamon neighborhood, seizing 12 buildings. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights described it as the largest offensive south of the capital “in months.”

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS south of the Syrian capital, Damascus.

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS south of the Syrian capital, Damascus.

By Omran for strategic studies -Nawar Oliver

While it’s unclear if ISIS timed the attacks as a response to the U.S. and Russian statements, the militant’s new offensives serve as a reminder that it may be too soon to sound the death knell for ISIS in Syria, experts said.

At the height of its power in 2015, ISIS commanded territory in Iraq and Syria larger than the size of Ireland. This year, however, separate Russian and U.S. military campaigns pushed militants out of all their major strongholds across the two countries. While Putin and Trump call this a complete defeat others remain skeptical.

“I think that there’s a bit of ambiguity and confusion with regard to what a defeat might look like,” Simon Mabon, a lecturer in international relations at Lancaster University and co-author of The Origins of ISIS, told Syria Deeply.

“Whilst some will talk of a military defeat and the liberation of Syrian-Iraqi territory, the bigger and arguably much trickier struggle is about defeating the ideology and preventing the group – or a manifestation of it – from re-emerging,” Mabon said.

Earlier this month, Sergei Rudskoi, a senior Russian military officer claimedthat “not a single village or district in Syria under the control of ISIL.”

According to the SOHR, ISIS still controls 3 percent of Syrian territory, or 5,600 square kilometers (2,162 square miles). ISIS is present in southern Damascus, in “large parts” of the Yarmouk camp as well as in parts of the al-Tadamon and al-Hajar al-Aswad neighborhoods, where they are battling government forces.

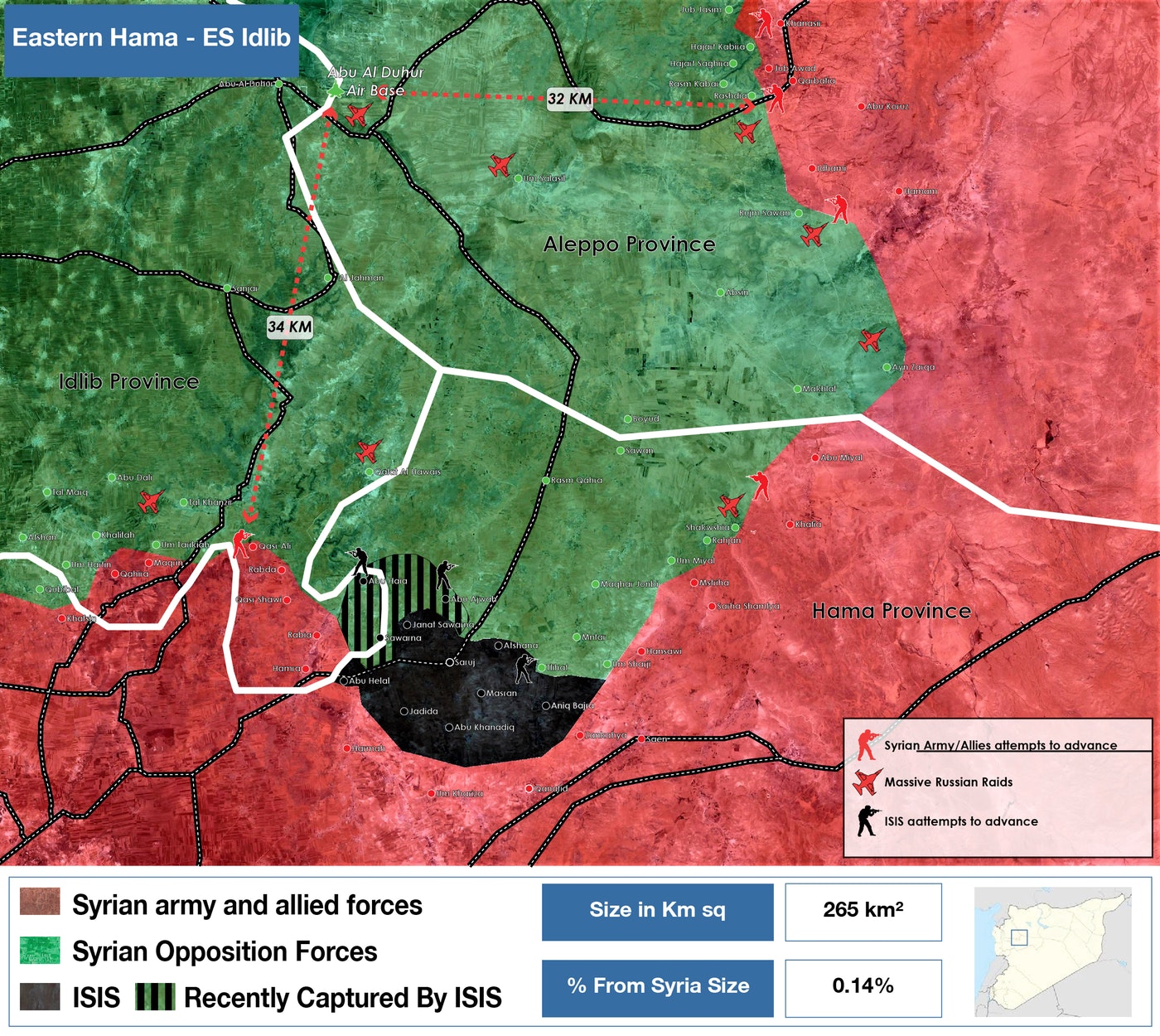

ISIS is also active in desert regions east of the government-held town of Sukhana in Homs province as well as in a small enclave in northeast Hama, where it is engaged in fighting with the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham alliance.

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS in Hama province.

By Omran for strategic studies -Nawar Oliver

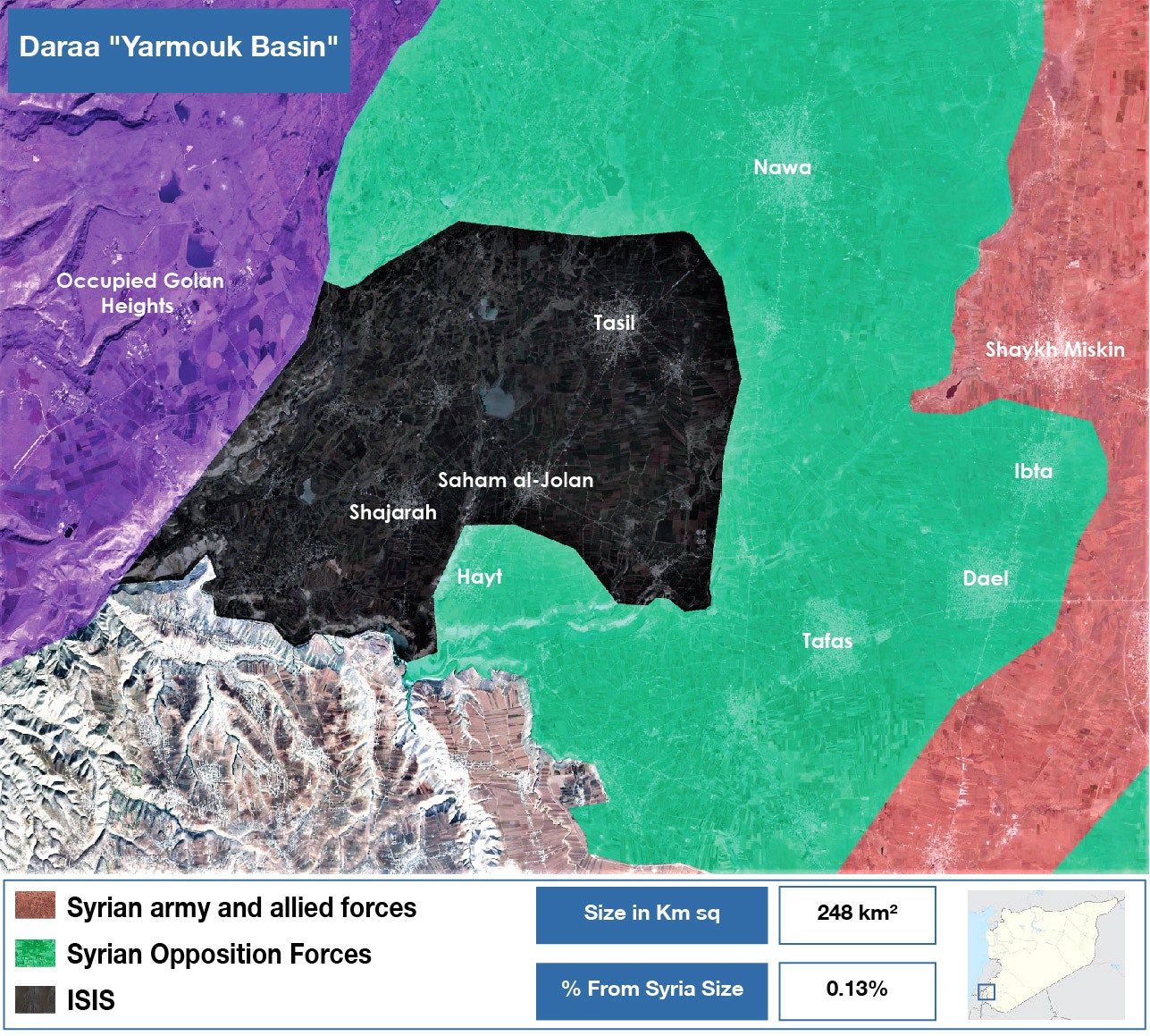

Militants also control at least 18 towns and villages in Deir Ezzor province, where it is battling both the Syrian government and the U.S. backed Syrian Democratic Forces. In Syria’s southern province of Daraa, ISIS controls a small enclave close to the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, where it has previously clashed with rebel forces.

A map of control showing territory held by ISIS in the southern province of Daraa.

By Omran for strategic studies -Nawar Oliver

Some White House staff and French President Emmanuel Macron said they were wary of Russia’s claim of victory on the ground. “We think the Russian declarations of ISIS’ defeat are premature,” an unidentified White House National Security Council spokeswoman told Reutersin a report published Tuesday.

“We have repeatedly seen in recent history that a premature declaration of victory was followed by a failure to consolidate military gains, stabilize the situation, and create the conditions that prevent terrorists from reemerging,” she said.

The militant’s last vestiges of territory are coming under severe strain by a wide array of rivals. It is only a matter of time before militants are driven to rugged hideouts in Homs and in the Euphrates Valley region. But as military battles subside across the country, a slow-grinding and methodical campaign should kick off to prevent an ISIS resurgence.

“To properly talk of a victory over the group, the conditions that gave rise to them must be eradicated. By that, I mean that people must improve their living conditions, be granted better access to political structures and to be able to exert their agency in whatever way they wish,” Mabon said.

“To fully defeat ISIS, such conditions must be addressed, preventing grievances from emerging that force people to turn to groups such as ISIS as a means of survival,” he added.

However, with military operations against militants still underway, there has yet to be any significant attempt to battle the ideological residues of the group or address the grievances that led to its emergence.

In an attempt at countering ISIS’ ideology, activists and Islamic scholars set up the Syrian Counter Extremism Center (SCEC)in the countryside of Aleppo in October. However, the so-called terrorist rehabilitation center has limited funding, giving it little ability to prevent the return of ISIS, especially after hundreds of ISIS-affiliated militants and defectors flocked to opposition-held areas in northern Syria in recent months.

Iraq, whose military also declared victory over ISIS this month after driving militants from their major strongholds, is already confronting a possible return of the extremist organization, in a further indication that claims of victory are premature.

According to the Iraq Oil Report, a new armed group, hoisting a white flag that bears a lion’s head, has recently appeared in disputed territories in northern Iraq. Citing local leaders and Iraqi intelligence, the report claimed that some members of the new group are known to have been members of ISIS. This has given rise to fears that ISIS may be “regrouping and rebranding for guerrilla warfare,” the report said.

A regrouping of ISIS would not come as a surprise, especially since militants can still capitalize on grievances in marginalized Sunni communities across Iraq and Syria.

“Across both states, Sunnis had been persecuted and marginalized, politically and economically, along with the physical threat to their very survival,” Mabon said.

“Whilst many are fearful and angry of ISIS, the deeper issues of marginalization and persecution remain.”

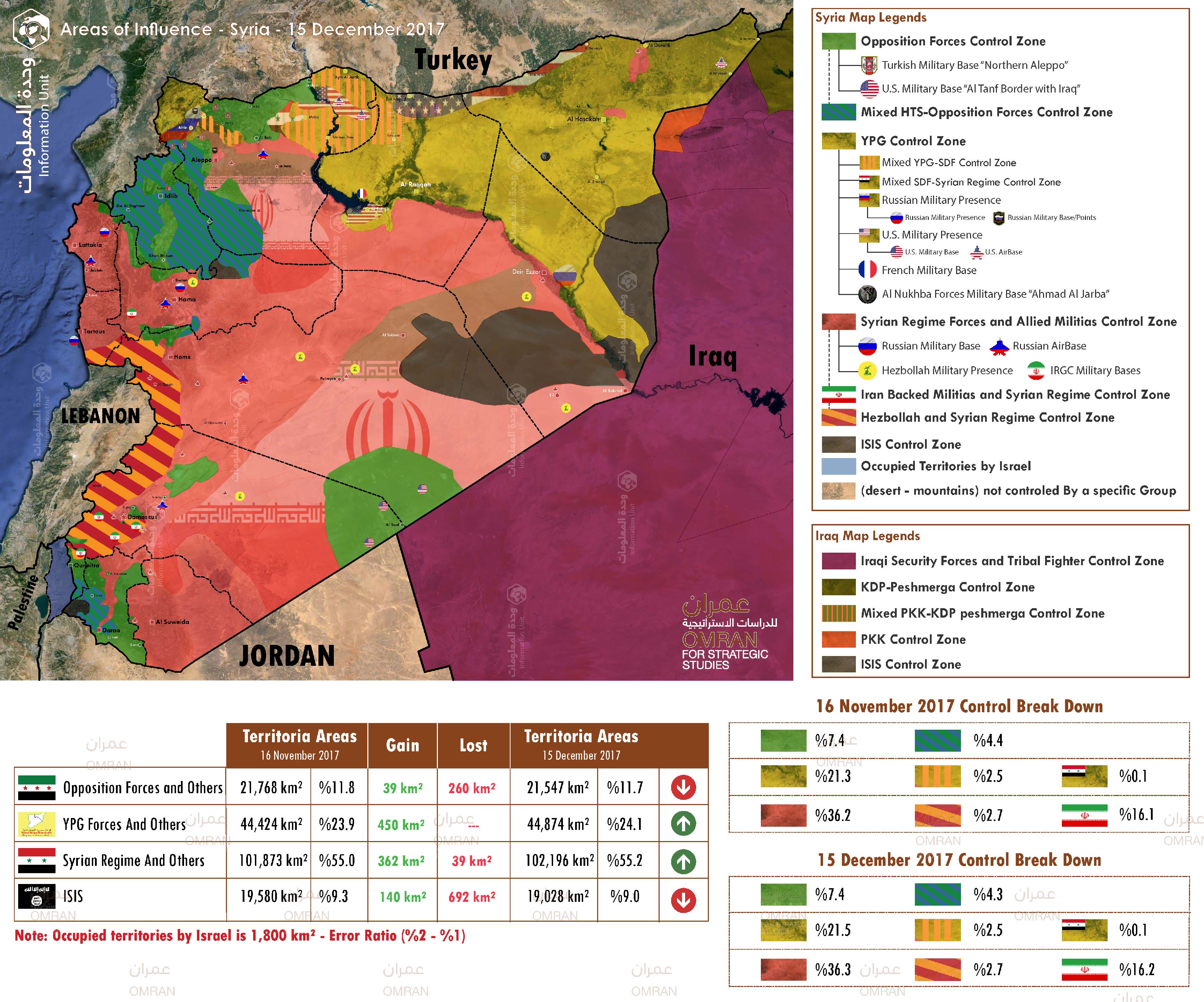

Map of Control and Influence: "Syria 15 December 2017"

Damascus

- December 7, inside sources, reported that Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham-affiliated combatants who were not pre-war inhabitants of Eastern Ghouta will be evacuated to Idleb governorate in the coming weeks. This development is pursuant to an agreement reached between armed opposition groups in the area and the Government of Russia.

- December 8, media sources indicated that representatives from the Syrian Regime have reached an agreement on the terms of a reconciliation agreement with the Negotiation Committee of Raheiba, in Raheiba subdistrict, in the eastern Qalamoun region of Rural Damascus governorate.

Important Note The most important terms reportedly included: implementation of a ceasefire in exchange for the entry of basic humanitarian aid and water; the establishment of a Syrian Regime local governance structure and the dissolution of all local opposition administrative structures.

- December 10, media sources claimed several ISIS commanders have evacuated Yarmouk camp and Hajar Aswad over the past month. Unconfirmed reports indicate they have relocated to ISIS-affiliated Jaish Khaled Ibn Al-Waleed-controlled areas of southern Syria.

- December 12, Clashes have continued in the vicinity of Bait Jan, in Bait Jan subdistrict in Western Ghouta, between opposition forces and Syrian Regime backed by Pro-Iran Militias. At present, advances by both parties remain tentative.

Important Note The humanitarian situation in Eastern Ghouta continues to deteriorate. Bread pack prices reached 1,900 SP, 1kg of rice is currently at 4,000 SP, and most day-to-day essentials are scarce in public markets.

Southern Front

- December 7, Hezbollah and Pro-Iran militias have reportedly deployed reinforcements to Jidya and Deir Eladas, located west and north of As-Sanamayn in Northern Daraa.

Al Hasakeh

- December 8, media reports claimed the U.S.-led international coalition sent a sizeable weapons shipment to the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). This shipment reportedly entered Al-Hasakeh governorate through the Syria—Iraq Fishkabour border crossing.

Important Note Last weapons shipment to enter the area was reportedly delivered on November 23, on November 24, President Trump reportedly informed President Erdogan that the U.S. intended to end its support to the SDF in Syria.

- December 12, humanitarian conditions in Shaddadah camp have continued to deteriorate. Of note, Shadadah camp is located between Al-Hasakeh city and Shadadah town. Reports indicate the total number of IDPs in the camp is now at least 6000 individuals, 90% of which were displaced from Deir Ez-Zor governorate on account of ongoing military operations.

Important Note The camp’s inhabitants reportedly suffer from a lack of basic food items, especially bread, as well as limited WASH and medical support. Unconfirmed reports indicate that around 150-200 people have been evacuated to Damascus each week since the start of December for medical treatment. Generally speaking, IDPs in Al-Hasakeh governorate continue to experience difficult conditions, especially given the limited capacity of existing camps to host all those displaced from Deir Ez-Zor governorate as well as worsening seasonal weather conditions.

Aleppo

- December 6, inside sources, indicated that airstrikes targeted Al-Azzan mountain, located 19 km south of Aleppo in the vicinity of Azzan town, Jebel Saman subdistrict. According to these sources, the attacks were launched by the Government of Israel and targeted an Iranian backed militia (Badr Organization) military base established in 2015.

Important Note December 1 and 4, Israeli airstrikes also targeted Government of Syria-controlled munitions storage facilities located between Kisweh and Sahnaya, south of Damascus city, and in Jamraya, in Qudsiya subdistrict.

- December 9, the Syrian Interim Government issued a statement claiming to have held a meeting with 37 opposition forces representatives in northern rural Aleppo, which concluded with an agreement to establish a ‘National Army’.

Idlib

- December 10, the Salvation Government issued a statement in which it announced the Syrian Interim Government would have 72 hours to evacuate all of its offices in Idlib governorate.

Important Note this comes after a statement on December 9, in which the Syrian Interim Government’s Head of Public Relations was cited as having described the Salvation Government as a terrorist organization.

Russia’s Brittle Strategic Pillars in Syria

With unreliable allies and a lack of experience with local power dynamics, Russia’s influence in Syria is built on fragile foundations

With political control fragmented among local powerbrokers in Syria, Russia’s overreliance on the Assad regime to protect its interests is a strategic threat. Despite current intersecting interests, neither the regime nor its Iranian allies are reliable partners. Competing and conflicting interests may finally come to a head once a political solution begins to take shape and Syria embarks on reconstruction, particularly in light of new regional arrangements.

Belying Vladimir Putin’s claim during his surprise visit to Syria that Russia is pulling back, these factors have in fact driven Russia to work to develop new tools that will enable it to maximize its gains and safeguard its interests in Syria.

Russian strengths and weaknesses

Russia reportedly has seven military bases housing approximately 6,000 individuals in Syria, and an estimated 1,000 Russian military police spread throughout the de-escalation zones and areas recently reclaimed from the opposition as a result of reconciliation agreements. Russia has also entrusted several private security forces with the task of carrying out special missions ostensibly in its war against ISIS and with protecting Russian energy installations and investment projects; these include the paramilitary group, ChVK Vagner, which, according to sources, has around 2,500 individuals on the ground in Syria.

But Russia realizes that it is not strong enough to guarantee its interests in Syria on its own and that it must rely on local partners to do so. Hence, Moscow is making efforts on two separate fronts. One is vertical – aiming to establish lasting influence within state institutions, particularly the military and security apparatus – by investing in influential decision makers, such as General Ali Mamlouk, director of the Baath Party’s National Security Bureau, and General Deeb Zeitoun, head of Syria’s General Intelligence Directorate, two of the most prominent security men.

The other is horizontal in nature. Russia is keen to develop relationships with local powerbrokers directly in order to build inroads with local communities with a view to balancing Iran’s growing influence within Syrian society. These relationships could be used as leverage to sway political negotiations towards Russian interests, while also recruiting them as local partners and guarantors for Russian investments.

Reaching out

The Russian Reconciliation Centre for Syria at Hmeimim Airbase plays a key role in communications with local powerbrokers; however, the communication mechanism and those responsible for it vary according to who controls the relevant areas. In coordination with the National Security Bureau, Russia has been able to engage with local powerbrokers in regime-controlled areas, including various political parties, local dignitaries and religious and tribal leaders, through Reconciliation Centre staff. It has also been able to communicate with the Kurds via military and security channels like Hmeimim Airbase and the Russian Ministry of Defence or via political channels managed by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in coordination with Hmeimim.

But Russia faces a dilemma communicating with local powerbrokers in opposition controlled areas and dealing with the influence of multiple regional actors. To overcome those challenges, it has employed several mechanisms to communicate with these groups in an attempt to co-opt them, using important political figures such as Ahmad Jarba to communicate with local leadership in besieged areas like Homs and Eastern Ghouta, and resorting to local reconciliation committees (primarily made up of local dignitaries and technocrats associated with the regime) that possess their own communication channels that can be used to communicate with the local opposition, as was the case in Al-Tel shortly before the Free Syrian Army’s withdrawal.

According to an activist from northern Homs, Russia is also very much dependent on cadres of Chechen Muslim military police, fluent in Arabic, to communicate with local leaderships. In addition, Moscow has used Track II diplomacy to network with local powerbrokers and open up back channels through relationships with regional powers.

Russia has so far employed the ‘carrot and stick’ model when communicating with local powerbrokers to ensure its influence, offering up benefits like security protection and financing, while guaranteeing them a place at the negotiating table and a share of reconstruction revenue. But based on past form, more heavy-handed measures to pressure local powerbrokers, such as making them targets of future military operations or playing on local rivals to marginalize or giving preference to one group over another in a political solution and reconstruction arrangements, remain on the table.

Enduring challenges

Although it has made strides stabilizing its military presence and legitimizing its security arm in Syria, Russia still faces challenges generating leverage within state institutions and Syrian society where Iran opposes Russia's efforts. The regime’s many centres of power, reliance on militias and weak institutions limit Russia’s efforts to consolidate its influence in the rest of Syria. Similarly, Moscow is finding it difficult to communicate with Syria’s many powerbrokers and differentiate between their demands, references and allegiances to other regional powers – making Russia’s strategic pillars in Syria all the more fragile.