Omran Center

The Syrian Security Services and the Need for Structural and Functional Change

Executive Summary

Systemic, functional, and structural change in the security services is a crucial issue that awaits objective solutions that take into account the rapidly shifting circumstances and variables throughout Syria. Because security reform is a complex process, it will be remedied – in light of Syria’s particular situation – by neither pre-packaged reform theories nor theses that ignore the nature and importance of national security while overlooking the necessity of cohesion and preventing collapse. Rather, theories are needed that entail a professional nation-wide effort consistent with local, regional, and international security requirements as well as the nation’s overarching goal: the construction of a coherent security sector.

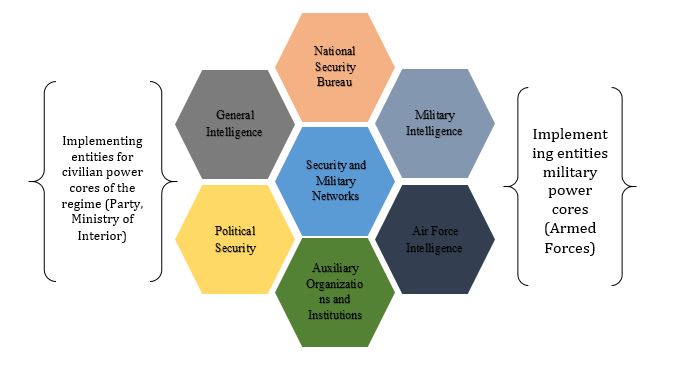

This study finds that the Syrian state does not possess a “security sector” from a technical definition perspective sufficient enough to deserve reform. As it stands, security work in Syria falls into two categories: The first concerns forces of control and repression. Among these are the Air Force and Military Intelligence Directorates, which are divisions of the Syrian Army and the Armed Forces; the General Intelligence Directorate, which is a division of both the National Security Bureau and the ruling party (the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party), while political security forms a division of the Ministry of Interior. The second category is military-security networks (such as the Republican Guard, the 4th Armored Division, and the Tiger Forces) that bear the responsibility of engineering the security process, determining its relationships and foundations, ensuring the regime’s security, and carrying out all measures and operations within society whenever there is sign of a security threat. Accordingly, two flaws and aberrations can be identified: The first relates to the security structure’s fragmentation, which in the past has helped curtail community activity, while also limiting its progress and development. The second issue relates to the function of these services, which is characterized by fluidity and boundlessness, with the exception of its permanent role consolidating and bolstering the regime’s stability. Indeed, any reform process of these services must target their function and structure at the same time.

Security is necessary and important in the context of any transition process, but this is particularly the case in a place like Syria, which operates as one of the sensitive regional and international counterbalances. To be sure, it is the most important of the state’s functions, whether in terms of maintaining social stability, protecting the country, or preserving its identity and culture from any encroachments. This need for security underscores that it is out of the question to dismantle security services, end their work, and not rebuild a national alternative with a cohesive structure and functions, as some are proposing. This is particularly true for the next phase of the new Syria, which has seen an increase in schemes that seek to cut across its national borders. Thus it seems that the requirement most consistent with the dualism of both rejecting the existing approach and confirming the necessity of security is the restructuring of the security services in the next phase so that they keep pace with those of developed countries that serve both the citizens and the nation.

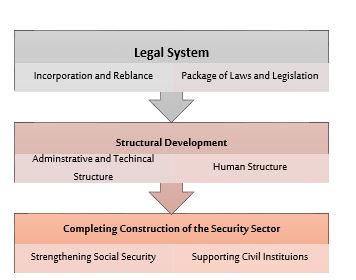

This study shows that restructuring measures should be based on principles of change, smooth transition, and cohesion – for fear that a sudden change could have repercussions for the cohesion of the country. This will ensure that the security services resume working within the national framework and complement state institutions. Certainly, these measures are a reflection of a series of political arrangements that signal the real desire for change and political transition. Consequently, they are void of any competitive, acquisitive or authoritarian calculations. To this end, the study proposes three phases for carrying out the reform and development process: The first phase relates to the legal system, which will ensure the principles of integration, rebalance, change of function, and strengthened oversight. The second phase is linked to the development of the human, administrative, and technical structures. As for the third stage, it will comprise a set of measures that aim to complete the construction of a cohesive and functional security sector.

Introduction

Ever since the Ba’ath Party came to power in Syria in 1963, its Military Committee has relied entirely on the intelligence services as a tool for strengthening its governance and entrenching its base. During the reign of Salah Jadid towards the end of the 1960s, Abd al-Karim al-Jundi (President of the Security Services and the National Security Bureau at the time) followed the policy of kidnapping and torturing the party’s opposition. After coming to power in March 1971 following his coup November 1970, Hafez al-Assad used the security services to control security, politics, culture, the economy, and even religion, turning them into powerful appendages of his authority that pervaded the nation, society, and public life. His son, Bashar al-Assad, did not deviate from this path, as these apparatuses continue to follow all of the same policies that endeavored to limit citizens’ activities by using security restrictions and surveillance. These institutions, in addition to the military establishment, were the regime’s first and last lines of defense by virtue of their firm discipline and operational engineering, which enabled them to create the Syrian Army’s sectarian structure. This has enabled the army to control leadership and power centers populated by Alawites and those who owe their absolute loyalty to the regime. This type of engineering became clear following the disagreement between Hafez al-Assad and his brother Rifaat, who almost overthrew him in the 1980s. Following the event, Assad restructured the army and security services, adjusting security operations so as to consolidate his rule and undermine both political movements as well as the overt and covert ways for people to reject his regime.

In 2011, the Syrian uprising broke out having been caused largely by a hidden, yet growing, popular discontent directed towards the security services’ destructive and authoritarian practices that denied even of the most basic human rights. The security services followed these developments – seeing the gatherings of demonstrators as no more than “riff-raff, rebels, and terrorists” – and served as the main force to carry out policies of repression and systematic violence against the revolutionary movement. With the spread of the movement and the sharp spike in the level of the conflict, the international community has desperately attempted to put established rules in place to initiate a “political process” along a negotiated path. However, this process is still stalled as of the time that this study was prepared. All signs indicate that the necessary political solution, according to the international community, includes “preserving state apparatuses, chief among them the institutions of security and defense.”

As mentioned above, the study of Syria’s security situation, as well as discussion about the need for functional and organizational change in the security services, represent a compound problem that must be unpacked. Indeed, any political path that anticipates solutions to the Syrian crisis without taking into account the security component – along with its excesses and questions about its role in the Syria’s transition and future – will not work. Therefore, this study attempts to provide an accurate description of the security services’ current functions and program so as to touch upon the most significant levels of discernable deficiencies, as well as the conclusions that can be derived from this that will help create an objective picture of the security issue for the future.

Assumptions: The study proceeds from a number of assumptions, namely:

- Any transition process that is not accompanied by a systemic change in its security services so as to render it capable of protecting the political transition will only represent superficial change that will not strengthen social and political stability and only consolidate the pillars of the ruling regime.

- The reform process’s connection to engineering a Geneva-brokered political solution is a key structural link. Thus, the more that the solution is set up for a true process of change, the more it will clearly influence the reform process and transformation.

- The reform process does not work without positive engagement from both international and regional actors, particularly after the Syrian “crisis” became the international issue par excellence. This requires vigorous national efforts, which include enlisting regional and international actors to support and fund the political and transition processes as well as their accompanying reform policies.

- The study adopts the principle that the nation’s monopoly on central functions related to sovereignty (such as security, defense, and international affairs) is essential. That said, the study is applicable to scenarios where Syria’s territorial unity is preserved whether through the principle of administrative decentralization or some forms of federalism where the central state maintains the operation of central security services.

- The reform process runs into severe opposition from both the security services themselves as well as the networks of the ruling regime on account of the “objectivity” of defending their interests, which the reform process will reconfigure on all levels, particularly with regards to organization and institutionalization. This reform will transfer the security services’ interests to authorities tasked with overseeing and monitoring both mechanisms of funding and all other planning processes.

Study Approach: This study follows both descriptive and behavioral approaches to show the philosophy and reality of the security services, their current organizational and functional nature, as well as the desired outcome. In identifying flaws and structural setbacks, the study relies on interviews with officers, individuals, and dissident security experts. Their insights constitute an essential documentation for finding out information about security operations and their methods, which the study considers to be a key foundation for the cohesion of the security services and their complete loyalty to the regime. Moreover, the study uses a comparative method in presenting its examination of the most important security reform experiences in Arab Spring countries in order to measure them against Syria, explore their most important lessons and conclusions, and carry them over as necessities that should be recognized and taken into consideration during Syria’s own security reform process.

Previous Studies: The most important studies published concerning security reform issues in Syria can be summarized as follows: The first is entitled Syria Transition Roadmap, published by Syrian Expert House and the Syrian Center for Political and Strategic Studies in 2013, the ninth chapter of which details the restructuring of Syria’s security services by surveying the following:

- The most important security services have revealed their role through policies of systematically repressing the Syrian uprising and have been documented carrying out its worst massacres.

- The general goals, initiatives, and mechanisms of reform.

- A proposal for a new Syrian security system based upon dissolving all security services with the exception of the police forces, which had a detailed explanation devoted to them that recommends restructuring the internal security forces.

That said, this study was completed in the context of the ongoing conflict in 2013, which has subsequently become more complex in light of certain types of crimes, the sheer volume of accumulating security issues, and the number of security threats from either religious or ethnic sources that have begun to overlap. Moreover, these complications are further compounded by the appearance of specific challenges, some of which relate to the continuing effects of security reform in Arab Spring countries, not to mention the multiple actors and stakeholders in areas of Syria that experience relatively stable forms of governance and local administration.

Similarly, the “Day After Project” designed to support democratic transition in Syria in 2013 published an important chapter on “Reforming the Security Sector,” which proposed dissolving the current security services and establishing new intelligence agencies (both for military and foreign affairs). The project proposes a 14-month timetable for initiating reforms based on the theory of jettisoning the security structure and establishing new security formations assigned local security functions, such as that of civilian police forces. The study subjected the security landscape to deconstruction and restructuring theories while at the same time pointed to the absence of a so-called “security sector.” The study further indicates that all security services are divisions of control belonging to different institutions, the most important being the army, Ministry of Interior, and the Ba’ath Party. Based on this view, the main actors in control of security and its institutions are networks engineered by the regime so as to ensure that these institutions serve to strengthen its authority. In this way, the regime relies on specific Alawite families that compete amongst themselves to show their loyalty and maximize their private interests. This structure makes it a strategic matter to break up these security networks while simultaneously creating a cohesive security sector based on the necessity of functional and structural change to the security services.

Yezid Sayigh’s Carnegie Center studies, which monitor and analyze the dynamics of security reform in Arab Spring nations, constitute an essential perspective that this study relies on to extract the most significant obstacles and issues that resist reform processes. His most important studies include: Crumbling States: Security Sector Reform in Libya and Yemen and Dilemmas of Reform: Policing in Arab Transitions. In these studies, Sayigh deconstructed the security reform processes in these countries, which he saw as faltering for several reasons. Perhaps the most prominent factors he identified were the legacies of dictatorial and factional regimes and the politicization of transition processes. Moreover, he recognized the significance of these governments’ focus on terrorism and their unwillingness to take on any other serious security agenda or consider the political economy dilemmas of this process, particularly with regards to costs.

I. The Security Reality During Assad’s Rule

The Emergency Law enacted in 1962 and the declaration of a State of Emergency on 8 March 1963, along with subsequent constitutional amendments introduced under Hafez al-Assad in 1973 allowed the security services to exceed the powers granted to them by the laws and decrees under which they were created. They thus became a means to impose repression, commit acts of torture, restrict freedoms, and suppress public opinion, and moreover inflict heavy setbacks on Syrian society. As a concept, “security” means constant research and investigation for the sake of stability and civil cohesion. Under Hafez al-Assad, however, this principle was completely ignored and replaced by a conception of the security services as the private security of the ruling authority, whereby security agencies and other military and civilian sectors were either subjected to its control or created from scratch in order to control domestic interactions on all levels and forcibly exclude them from effective participation in the public sphere.

Philosophy of Security Work:

A survey of security work and conduct during the rule of Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar al-Assad reveals that the philosophy of security activity involved a binary of: loyalty to the regime and private interests, which constituted the real guarantee that they would remain the principal actor in all domestic interactions and an absolute bulwark of the ruling regime.

The main features of this philosophy are as follows:

1.Absolute Powers and the Link Between Community Activity and Security Trends:

The security services have received complete independence and wide-ranging powers in all aspects of political, economic, service, and social life as well as have adopted several methods of intervention. Perhaps the most important method is devotion to the principle of so-called “Approvals and Security Studies.” The essence of this principle is that it gives the security services the right to “object” to all community practices and demands, which results in intrusion into the simplest aspects of everyday life, from obtaining a street vendor’s license, to registering real-estate and inheritance information, to holding membership to parliament, to promoting army officers, forming cabinets, or even appointing judges. Just getting a public sector job, no matter how small or large, is contingent upon security research results that are determined to be positive towards the regime’s political position.

2.Competing for Loyalty and Inter-Agency Hostility

In asserting his control over the security services, Hafez al-Assad relied on the strategy of generating hostility and creating an atmosphere of competitiveness between the different security agencies and their senior officials. Performance indicators were linked to standards of absolute loyalty and obedience. In order to create a special interest sphere for security officials, they were given access to all levers of the state, which provided them with obscene wealth. At the same time, an entire file was prepared for each and every “corrupt individual and transgressor,” which facilitated the process of seamlessly terminating them if their ambitions grew too large. As for the era of Bashar al-Assad, he went about sowing conflict and mutual competition within his areas of influence and control. Control over border passages was distributed so that each one was subordinate to a specific security agency that rules and controls it and its revenue. Accordingly, boarder passages with Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey are each respectively subordinate to the General Intelligence Directorate, Air Force Intelligence Directorate, Military Security, and Political Security.

3.Compounded Fear of the Security Forces:

Over time, the condition of fearing security, embodied by the culture of fear propagated by the security services themselves, grew by leaps and bounds, as did weariness about surveillance within institutions. This transpired as a contradictory sectarian structure was enshrined within the decision-making centers of each government branch. Moreover, this pervasive fear spread as the culture of “reporting” deepened in society and within the security establishment itself – as making mistakes, whatever they may be, was constantly feared. Within the community, restrictions proliferated that hampered people’s activities, keeping them bound and fearful of taking any collective or individual action. As for internal fear, it comes from signs of negligent performance of either security tasks or any action in which loyalty and belonging to the ideology and doctrine of the “nation’s leader” is minimized.

4.Duties Related to the Ruling Regime’s Security

Totalitarian and autocratic states impose major duties and burdens on the security services, which bring them into alliance with the ruling regime. These duties connect their fates with the survival of the regime, putting the regime’s security ahead of its internal security issues on different social, political, safety, and economic levels. This has increased the number of abuses committed by security services, inflated their roles in carrying out repression, and deepened their connection to systematic legal and human rights violations. Over the past few decades, a certain security doctrine has been propagated that justifies the transformation of the state’s security functions into a goal in and of itself that is separate from the rest of the roles and functions of the state. The allocations for essential state functions, such as education and health services, have in many cases been reduced so as to provide greater resources for security, which maintains its survival at the helm. In this way, it ignores the foundations for building security services, which should be preserving the security, peace, and the stability of the nation and its citizens.

5.Restricting Political Activity

Throughout Assad’s rule, the security strategy has aimed to promulgate the philosophy of separating society from politics, both in word and deed, rendering it the exclusive domain of the ruling family and its supporters while denying and marginalizing the middle class and subjecting its intellectuals and innovators to strict surveillance. This approach has effectively linked the middle class to several organizational structures that fall under the umbrella of the Ba’ath Party, thus making it interact with, and become influenced by, only a small partisan circle. Those who fall outside of this circle, are numerous and unsuccessful because of their lack of access to state tools and mechanisms, not to mention their direct targeting at the behest of security institutions.

The security services strove to reduce politics to the figure of Hafez al-Assad in theory, practice, and approach, while also working on disseminating “his values and achievements” among all society’s classes and institutions. This focus bordered on deification, which resulted in an absence of true political representation, instead replacing it with another deceptive and rigid politics based on authoritarian and self-interested balancing acts and calculations.

6.Exhausting and Overwhelming Bureaucratic Structures

The regime has relied on a policy of controlling the capital city and the rest of Syria’s provinces according to the principle of overwhelming their administrative, service, and social structures with a massive number of branches, each with different overlapping and contradictory authorities and multiple functions. This has generally left citizens to come up with their own living solutions within the margins opened up by “red lines,” “national security,” and “national unity” cultures that have left them susceptible to exhaustion if they stray outside of them. It may reach the point that citizens continue to turn to the security services over a long period of time without ever getting their problems attended to, simply because mutual coordination between these services has been eliminated without any legislative or legal action. Furthermore, most branches dispatch several agents to follow and monitor the work of other official security services. This lays the foundation for contradictory policies, favoritism, and deepens the culture of reporting, which aims to either let a certain agent carry out other agents’ work or to coordinate with them to ignore “offenses committed” for their own collective benefit.

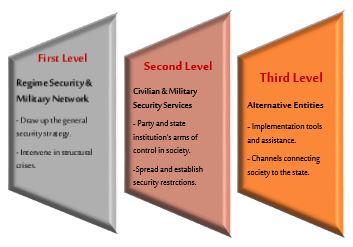

As a general outcome, the philosophy of security work in Syria is based on enshrining a group of security rules, customs, and standards that completely bind Syrian society, render it immobile, and push it to deduce the limits of what is permissible and forbidden when it is not exposed to regime security. This process has always involved intervention from security and defense institutions to manage political and government affairs until they literally become the source for laws that govern society. This hampers the developmental or reformative action that restructures the authoritative system of action and links its functions to serving citizens and their advancement. The figure on the left clarifies the levels of security work and shows the role each plays within this philosophy.

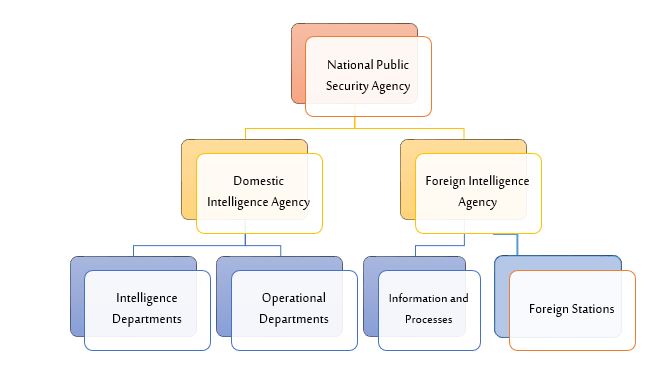

Security and Intelligence Services: Tasks and Structure

The security and intelligence services are comprised of four general directorates that are supervised by the National Security Bureau (NSB). The main headquarters for all of the services is located in the capital and includes four central branches. Falling under this directorate are branches located in every province that contain offices with specializations corresponding to those of the central branches. In other words, the branch is a microcosm of the general administration. The figure below clarifies the security services’ general structure.

1. National Security Bureau (NSB)

This is the office that took the place of its former counterpart by virtue of Presidential Decree No. 36 in 2012 shortly after the bombing of “the Crisis Cell operation room in the National Security building” in 2012 which was responsible for the security agency’s plan to counter the uprising and protest movement. The NSB was assigned the task of “drafting security policies in Syria” and presided over by the former director of the Directorate of Intelligence Major General Ali Mamlouk.

The Regional Command of the NSB was previously presided over by Mohammed Saeed Bakheitan, who is considered one of the members of the old guard that kept their leadership seats in the Ba’ath Party’s 10th Regional Congress alongside Farouk al-Sharaa, General Hasan Turkumani, and Major General Hisham Ikhtiyar. The former NSB had been subordinate to the regional command of the Ba’ath Party, convened weekly, and decided on a number of important issues pertaining to the country’s security. After the 2012 Presidential Decree, the NSB was made directly subordinate to the President’s Office and, under Mamlouk’s leadership, it shifted from being responsible for coordinating the security services and submitting general periodic reports and summaries to being more focused on leadership and guidance.

2. General Intelligence Directorate (GIC)

The General Intelligence Directorate (GIC) was previously named “State Security” and established by Decree no. 14 in 1969 after Hafez al-Assad assumed power. The directorate is directly subordinate to the president under the name “Unit 1114” without going through any state body or ministry except when coordinating with the NSB. The GIC encompasses 12 central branches in addition to active sub-branches in each province. Furthermore, the directorate includes the Higher Institute for Security Sciences, which was established in 2007 so that state representatives and diplomatic missions undergo intensive security trainings. The GIC is notable by its large number of civilian contractors and its officers, who are assigned by the Ministries of Defense and Interior.

According to the law that established the GIC, it is a civilian department even though all active military personnel are commissioned by the Ministries of Defense and Interior and hence report to them financially and organizationally. As for other civilian members of GIC, they are subject to the State’s uniform workers code. Accordingly, military officers overwhelmingly dominate positions of power, leadership, and agenda-setting posts, while civilians carry out administrative work in branches under the authority of military personnel. The percentage of Alawites among managers and heads of departments is approximately 70%, whereas the remainder belong to other sects. Recruits in the Syrian Army are selected to go to the directorate and tasked with guarding and protecting administrative workers.

Structure of the General Intelligence Directorate

- Director of the GIC: Appointed by Presidential Decree, the current director is Major General Mohammed Dib Zaitoun, who was appointed by Presidential Decree in 2012 following the tenure of Major General Ali Mamlouk, who was then appointed president of the NSB.

- Deputies to the GIC Director: There are multiple deputies working under the GIC Director, each of which is appointed by decree and his or her powers, specializations, and rights, and duties are determined by a resolution issued by the director. Current deputies include Major Generals Mohammed Khalouf and Zuhair al-Hamad.

- Information Branch 255: This branch is tasked with obtaining all political, economic, and social information and to monitor the religious, partisan, and media sectors. Information is collected to this branch from the other central branches, provincial branches, and other sources. This information is then archived and utilized by GIC. Thereafter, resolutions are issued such as travel bans and ordering the “arrest” of citizens whom the directorate’s branches have incriminated.

- Investigative Branch 285: This is a central branch that specializes in investigating transmitted information from branches, sources, and agents. Most detainees arrested by provincial branches are referred to Branch 285 after they have been questioned by investigation departments. It has become customary that the president of this branch, as well as most of the investigators in it, are Alawite.

- Counter-Terrorism Branch 295: Otherwise known as the Najha Branch, this branch specializes in dispatching consignments of volunteers to work on behalf of the GIC. Additionally, the branch trains individuals within the GIC (namely military personnel) in military and security sciences, works on increasing their levels of fitness and physical capabilities, and trains them to carry out their main missions of raiding, kidnapping, assassinating, and counterterrorism. This branch was among the first that the GIC relied upon to suppress the protest movement in Daraa and Baniyas.

- Counter-Espionage Branch 300: This branch specializes in keeping tabs on foreigners and those suspected of working with foreign actors. This branch also surveils government and private institutions that work abroad and observes the work and relationships of political parties and politicians. This branch has a working relationship with the Technical Branch as well as the telecom company SyriaTel, which is owned by Rami Makhlouf.

- External Branch 279: This branch is tasked with managing the external intelligence stations in embassies and consulates around the world. It investigates incoming information that pertains to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and any other ministries that carry out foreign missions and deployments. Moreover, the branch closely monitors and surveils Syrian expatriate citizens and all of their political and social activities.

- Technical Branch 280: This branch is authorized to conduct eavesdropping, communications jamming, and technical surveillance missions. It also helps other branches with all of their technical support needs and carries out engineering, electrical, and mechanical works in the GIC and its branches. Its most important departments include wired and wireless communication equipment, computers, intelligence gathering, mail monitoring, encryption, internet, the Ghadir Project, and the satellite jamming project.

- Internal Branch 251: This is the name of the GIC branch in the capital Damascus, and is responsible for counter-intelligence work within Syria, particularly in Damascus and its suburb. The branch has an essential role in appointing government officials, presidents of unions and chambers of commerce, general managers of public corporations, university staff and heads, party trustees, as well as the appointment of key government positions in all divisions and ministries. Furthermore, it has become customary for the president of this branch to be exclusively Alawite. Former presidents include Bahjat Sulaiman, Mohammed Nasif, and Tawfik Younis and, currently, Ahmed Dib serves as the branch’s president. The branch houses a department known as Department 40, which is, based on its powers and engagements, considered to be a total directorate, the management of which has long been run by Hafez Mahklouf.

- Training (or Ghouta 290) Branch: It is authorized to run all training programs that aim to improve the GIC’s staff knowledge and skills relating to either theoretical security sciences, management, technology, or technical training.

- Economic Branch 260: This branch monitors and investigates all economic and administrative activities by citizens, private companies, institutions, commissions, or publicly-owned corporations.

- Branch 111: Reports to the GIC director’s office, and organizes all affairs directly supervised by the director and is involved in all other branches’ matters. Most of those employed in this branch are Alawite.

- GIC Provincial Branches: These branches are located in the different provinces and given a three-digit number, each of which contains departments analogous to those of the central branches in Damascus. These branches have the same competencies as their central counterparts and perform the same work, however within the confines of their province. Every branch operates and oversees divisions, departments and sub-units scattered throughout their province, as each town or village has a security officer who is responsible for it, conducts security studies, and is tasked with calling on other security branches. In this way, the GIC oversees every region and comprises thousands of agents, informants, and delegates in every city, village, as well as public and private institutions.

3. Military Intelligence Directorate (MID)

The Military Intelligence Directorate (MID) falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Defense administratively, financially, and in terms of obtaining armaments. However, the Minister does not have any authority over it. Conversely, the MID is involved with appointing the Minister of Defense, his deputies, chiefs of staff, and dictates the transfer of army officers and personnel. Meanwhile, the MID’s chief is appointed by the president. Upon its establishment, the MID was made responsible for military units, borders, as well as the security of officers, personnel, and military installations. The Chief of the MID is currently Mohammad Mahla, who was appointed in 2015 following his predecessor Rafiq Shahadah’s tenure.

The MID, which is considered to be the Syrian Army and Armed Forces’ security division in society, goes by the motto “safeguarding the principles and values of the establishment,” which it uses as a pretext to instill an ethos that “Assad’s army is sacred.” At the same time, this approach is used to justify its role as an overseer and partner of other security services in their efforts to police local activity via determinants that bolster the regime’s authority. The directorate’s officers – the majority of which herald from a variety of different military units – are tasked with monitoring the behaviors of military personnel based on standards of loyalty and adherence to the regime’s command. The MID also constantly investigates any potential reform initiatives that may be carried out by commissioned or non-commissioned officer ranks, volunteers, and conscripts.

Structure of the Military Intelligence Directorate

First: Central Branches operating in Damascus:

- Branch 291: This is the administrative affairs branch, also known as the Personnel or Headquarters Branch. Several functions are assigned to the branch relating to the MID’s activities, central archive, human resources files and reports, as well as monitoring the performance of MID itself to prevent any breaches from within. The self-assessment of MID by this branch plays a significant yet supplementary role in the promotion, demotion, expulsion, or transfer of employees within MID.

- Branch 293: This branch is responsible for Officers’ affairs and security. From a practical perspective, it functions and acts as a security network/bureau on its own and not necessarily as a branch of MID. The branch handles evaluation and surveillance issues and monitors all army officers. Moreover, the branch plays an essential role in promoting, removing, and transferring army officers and appointing them to their departments. The branch chief has the ability to directly contact the President of the republic and submit reports directly to him.

- Branch 294 (Security Forces Branch): Tasked with surveilling the operation and movement of armed divisions as well as all armed forces (with the exception of the Air Force and Air Defense). This branch handles records of military bases and units, as well as artillery divisions and their levels of combat readiness and loyalty. Security officers in charge of military units are more loyal to this branch than their military units’s leadership. It is should be mentioned that all moves by army units must be approved, and coordinated by this branch. Finally, it assumes a supervisory power over military police and its divisions that are attached to military units and divisions.

- Branch 235 (Palestine Branch): This is one of the oldest and most important branches in the MID. Branch 235 is tasked with (both domestic and foreign) responsibilities equal in size to those of an entire intelligence directorate. While the branch is supposed to concentrate on countering threats by Israel and specializing in matters related to Palestinian organizations both domestically and abroad, its responsibilities have expanded significantly to include pursuing and infiltrating Islamic organizations, as well as trying to steer and control them through its own counter-terrorism department. This branch is also specialized in surveilling Palestinian refugees located in Syria. In fact, a sub-unit of the branch called the Commando Officers Unit specializes specifically in Palestinian Liberation Army affairs as well as those of armed Palestinian movements that are officially stationed in Syria (these include the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) founded by Ahmed Jibril).

- Information Branch: This branch focuses on data gathering and evaluation of all affairs relating to MID’s work and prepares different studies and reports related to this effort. The branch comprises many different departments, including a department for religions and political parties. It surveils local and international audio, visual, written, and internet media activity, and also works directly and indirectly with media outlets on matters of interest to the MID.

- Branch 211: This is named the “Signals Branch”, and is responsible for monitoring the army and security services’ wireless signals and encrypting them. The branch is also tasked with conducting technical surveys and wiretapping.

- The Computer Branch: This branch specializes in computer- and internet-related services. Its tasks include surveilling the internet, monitoring all virtual activity, intervening in hacker activity, and blocking or unblocking websites.

- Branch 225 (Communications Branch): This branch surveils all wired and wireless communication lines in the army and armed forces. It also supervises and follows up on the implementation of all communications projects in the country.

- Branch 248 (Military Investigations Branch): This branch is like the MID’s primary investigations commission for military security and considered to be the second worst branch in the MID – after the Palestine Branch – with regards to violations.

- Branch 215: This branch is also known as the raids and forced entry commandos. It differs from all other branches in that it comprises about 4,000 personnel trained in all varieties of skills utilized by Special Forces, including raiding, assassinating, kidnapping, and arresting wanted individuals.

- Patrols Branch: This branch conducts all central and peripheral leadership orders and directives regarding field security duties.

- Quneitra Intelligence Branch: Also known as Sa’sa’ Branc: It specializes in intelligence affairs in the occupied Golan Heights and PFLP forces. The branch also monitors the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) active in this area.

Second: Provincial Branches: These branches are spread throughout each province and, depending on the need, may have sub-departments, divisions and units in each administrative district of the province. Each branch is assigned a number.

A noteworthy and important observation in the MID is that approximately 80% of commissioned officers, non-commissioned officers, and personnel are Alawites, and the majority of them are commissioned by army units to MID with the exception of some conscripts who are assigned duties such as guards, gatekeepers, and raiding targeted sites. The MID is also in charge of the military intelligence school, which trains MID volunteers and personnel.

4. Air Force Intelligence Directorate (AFID)

The Air Force Intelligence Directorate (AFID) was established during the early days when Hafez al-Assad took office and remains the regime’s most loyal state body. It is famous for possessing the strongest manpower and best technical skills of all of the security directorates. AFID contains the lowest percentage of non-Alawite officers compared to other directorates. While AFID is theoretically subordinate to the Ministry of Defense in terms of its administration, finances, and armaments acquisition, the Minister of Defense does not have any authority over it. On the contrary, AFID, along with the MID, oversees the Minister’s work and has an important role in his appointment. Major General Mohammed al-Khuli has remained AFID’s head for a long period of time after Hafez al-Assad relied on him during security operations against his opponents after seizing power. This directorate’s main responsibility is to protect the Syrian Air Force, the president’s airplane, and to provide security when he is outside of the country.

Structure of the Air Force Intelligence Directorate

AFID contains six subordinate branches in Damascus, its own investigations branch, and six branches in the provinces :

- Administrative Branch: This branch is tasked with safeguarding all of AFID employee records. It also surveils its staff to prevent any security breach within it. It also has a role in the promotion, removal or transfer of employees within the directorate.

- Information Branch: Specializing in the directorate’s general information gathering and conducting various studies. This branch houses many departments, including the departments of religion and political parties. It surveils local and international audio, video, written, and internet media activity, and works directly and indirectly with media outlets concerning matters of interest to AFID.

- Investigation Branch: This operates in the capacity of the AFID’s primary investigation commission, and is infamous for being the worst branch in committing torture and other atrocious violations.

- Airport Branch: Located at the Mezzeh Airport, and is responsible for Presidential Airport security as well as the President’s airplane. Inside sources indicate that this branch is also responsible for intelligence missions related to the personal security of the president during his travels abroad.

- Operations Branch: Responsible for AFID’s domestic and international operations, including those related to the Air Force weaponry that require extensive foreign intelligence efforts. This branch coordinates with the Airport Branch when performing foreign intelligence operations related to the president’s security while he is in transit. Its agents are usually stationed at Syrian Airlines offices abroad.

- Special Operations Branch: This branch has a significant, widespread presence in all of Syria’s provinces in the form of departments. It performs combat operations with the help of requested units from the Air Defense, Air Force, military airbases, and even civilian airports, including the deployment of necessary weapons, munitions, and aircrafts.

- Provincial Branches: There are six branches in the different provinces covering all of Syria. They include:

- Regional Branch: Covers Damascus and its suburbs with headquarters in Damascus.

- Southern Region Branch: Covers Daraa, al-Quneitra, and al-Suwayda with headquarters in Damascus.

- Central Region Branch: Covers Homs and Hama with headquarters in Homs.

- Northern Region Branch: Covers Aleppo and Idlib with headquarters in Aleppo city.

- Eastern Region Branch: Covers Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa, and Hassakeh with headquarters in Deir ez-Zor.

- Coastal Region Branch: Covers Latakia and Tartus with headquarters in Latakia.

These branches each have corresponding departments spreading throughout provinces that do not house a main headquarters. They also have other departments and sub-units in other regions and administrative districts and villages according to the need.

5. Political Security Directorate (PSD)

While the Political Security Directorate (PSD) financially and administratively falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Interior, but it does not report to it in terms of its professional performance. Furthermore, PSD has a supervisory authority over the Minister of Interior, his officers and staff including all police units. In other words, it is practically independent in that it can communicate directly with the President. Indeed, this directorate is the most pervasive in society, interacts the most with civilians, is most widespread among citizens, and spans the entire country and all segments of society. Moreover, the directorate carries out copious exchanges with civilians, demanding work and construction permits approved by PSD, which has a vast reservoir of the regime’s information about citizens. This drives PSD officers and personnel to exploit their influence, accept bribes, and impose “tribute” on citizens on a massive scale. PSD officers and personnel are chosen by the Ministry of Interior, with the exception of the PSD head, who is appointed by a Presidential Decree. Major Generals Adnan Badr Hassan, Ghazi Kanaan, and Mohammed Dib Zaitoun are among the most prominent of PSD’s former chiefs. Currently, the Druze Major General Nazih Hassoun, who was appointed following the tenure of his predecessor Rustum Ghazali, serves as PSD president.

It has become customary for the PSD president to come from the security or military services’ leadership. Unlike its counterparts, the directorate is more of an administrative apparatus than a fieldwork civilian one in that it, to a large extent, serves an administrative intelligence role. Its responsibilities are entirely domestic in that it does not carry out any activities abroad like other directorates (with the exception of the Arab and Foreign Affairs Branch, which monitors Arabs and foreigners within the country). The directorate’s provincial branches are named after the provinces themselves (for example, the Political Security Branch of the Damascus Suburbs) instead of being assigned a three-digit number.

Structure of the Political Security Directorate

The directorate is made up of a number of branches in Damascus as well as the following branches located in the rest of the provinces:

- Police Security Branch: This branch handles all records pertaining to the directorate’s workers and conducts surveillance on them to prevent any internal breaches. It also plays a role in promoting, removing, and transferring PSD personnel. Of note, this branch also has files on all personnel of all ranks and functions working in the Ministry of Interior.

- Information Branch: This branch serves as a collection hub for all information and studies from other central and provincial branches. It consists of a number of different departments, including an espionage department and a department for students that concentrates on attendees and managements of universities, institutes, schools, and kindergartens. It surveils local and international audio, visual, written, and internet media activity. It also works directly and indirectly with media outlets concerning matters of interest to the PSD.

- Investigations Branch: This branch functions much like the PSD’s primary investigations authority. Central branches and those from other provinces hand detainees over to it who have committed crimes deemed serious by the regime.

- Patrols and Surveillance Branch: Employing a large number of personnel, this branch is tasked with carrying out patrols in Damascus and its suburbs. The branch conducts raids, makes arrests, and supports provincial branches when assigned.

- Parties and Entities Branch: This branch monitors the activities of political parties deemed “friendly,” which include the Ba’ath Party and even some opposition and hostile parties. Additionally, the branch monitors all political opposition activity and so-called terrorist groups, surveils mosques, churches, and all religious activities and functions, and grants permits to imams, preachers, mosque servants, and religious teachers. Moreover, it issues licenses to charitable and civic organizations and surveils both pro- and anti-regime meetings, conferences, and celebrations.

- Economic Security Branch: All information relating to public, private, and joint public-private economic ventures and activities collected by provincial branches is funneled to this branch, which also monitors all government departments. Additionally, it submits periodic presentations to the President of the Republic on economic activities and indicators. It archives information on employees who have been arrested for work-related reasons, and surveils employees’ religious lives.

- Correspondence Records Branch: This branch receives correspondence from all branches, departments, and other bodies and redirects them to intended recipients after PSD president’s review.

- Arab and Foreign Affairs Branch: All information related to foreigners and Arabs in Syria is handled by this branch. It receives and processes reports from outside of the country. It specializes in granting approvals for residence permits of foreigners as well as approving and monitoring their economic and social activity in Syria.

- Information Systems Branch: It houses the physical and digital personal records on all Syrian citizens, Arabs, and foreigners gathered by the central and provincial branches.

- Administrative Affairs Branch: Coordinating with the Ministry of Interior, this branch is tasked with fulfilling the central and provincial branches’ needs of weapons, munitions, equipment, furniture, facilities, and purchases.

- Signals Branch: This branch is tasked with the fulfillment of requests for the procurement of different types of wired and wireless communication devices for all branches, while also surveilling communications within the PSD and Ministry of Interior.

- Vehicles Branch: This branch is tasked with fulfilling the requests of all other branches for vehicles and its attachments.

- Provincial Branches: The PSD has a branch in each of the 13 provinces, except for al-Quneitra Province, which is covered by the Damascus Suburbs Branch that has a department called the “Quneitra Department.” Each of these branches also has sub-departments and divisions located throughout Syria in every administrative district. This enables it to provide security for the entire country and monitor all citizens. The branch’s departments and divisions recruit citizen informants from the general population who operate in their respective areas of residence. Informants submit their reports to their respective department or division that in turn archives and organizes it then forwards to the specialized branch in the province.

It is worth mentioning that most of those who belong to the PSD are graduates of police academies and colleges and interact directly with citizens to conduct special reports and studies. The percentage of Alawites in the PSD and its branches is less than their percentage in other directorates according to estimates by PSD defectors.

The Regime’s Military-Security Networks

The ruling regime has assigned the task of security strategies oversight to certain military units that profess absolute loyalty to the regime primarily as a result of special arrangements followed in the recruitment of its human resources by relying mostly on Alawites, as well as the nature of tasks assigned to them including inter-agency and intra-agency oversight. The regime also grants these units unrestricted powers to firmly put in check aspects relating to criminal and societal security that are not within the jurisdiction of the traditional official police force. One can assess the regime’s security policy by closely analyzing these networks that were mastered and attached directly to the regime. The most important units include:

First: Republican Guard

The Syrian Republican Guard Forces (RG) are considered the most prominent of the Syrian Army’s elite divisions as well as its most heavily armed. Their main task is to protect the capital from any internal or external threats. Thus, they are the only military unit allowed to enter Damascus.

Confirmed information on the RG is scarce, however some reports indicate that they are distinguished by their strong armaments. Furthermore, they are composed of nearly 10,000 soldiers spread throughout several different brigades and its officers are given a portion of Syrian oil revenues to maintain their loyalty. The establishment of the RG dates back to the end of the 1970s after armed clashes broke out in Hama and Aleppo between Hafez al-Assad’s regime and his Muslim Brotherhood opponents.

The RG maintain a high degree of Bashar al-Assad’s confidence, as he has pursued the same approach as his father in terms of appointing leadership positions of its brigades and regiments to members of specific Alawite families in Syria. For instance, at present, Major General Bassam al-Hassan heads the RG, which are tasked primarily with protecting Damascus City and preventing any local or foreign forces opposed to the regime from evolving within the city. The RG also dictates security rules and relationship schemes that govern inter-branch engagements as well as the relationship between citizens and the regime on the other hand. It is also considered to be the official state body responsible for the coordination of military and militia activities in Syria after the outbreak of the uprising, including the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, Lebanese Hezbollah, and Shiite Iraqi militias.

As the RG’s leadership is considered among the most prominent leaders nationally, its forces has intervened and thwarted serious threats and societal security risks including the Kurdish Uprising in 2004, the Alawite-Ismaili clashes in 2005, as well as Druze-Bedouin conflict in 2001. The RG forces are organized with several regiments and brigades operating independently but report administratively to the leadership of the RG. Its units and divisions are known with names and numbers ranging from 101-106. The most prominent include the following:

- Security Bureau, led by Brigadier General Bassam Merhej.

- 101 Security Regiment: Most of its leadership is from the Khair Baik family.

- 104 Airborne Regiment: Directed towards the Presidential Palace in Damascus.

- 105 Regiment: Known as the president’s lounge, as it was led first by Bassel al-Assad, then Bashar al-Assad, and then Manaf Tlas led it until his withdrawal from the army.

Perhaps the most important reasons behind the strength and cohesive nature of the RG that binds its forces together (which some security experts see as capable of carrying out a bloodless coup) are the following:

- The Alawite connection, which serves as the only guarantor of the RG and the regime’s continuity.

- Internal competitiveness.

- Departments tasked with surveilling one another.

- Direct lines of communication to the President.

- Maintaining the processes of appointing of dismissing RG’s leadership exclusively within the mandate of the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and the Armed Forces (Bashar al-Assad).

Second: The 4th Armored Division

This a division of the Syrian Army subordinate to the First Corps. It receives special training and support to make it the regime’s strategic safeguard. It was founded during the rule of Hafez al-Assad when his brother Rifaat, who led the “Defense Companies” responsible for the Hama massacres in 1982, established it. The Defense Companies were later integrated and merged into the Division after Rifaat was “exiled” in 1984.

According to French media sources, the 4th Armored Division consists of 15,000 fighters, the vast majority of which are Alawite. Moreover, the division is considered to be among the top units of the Syrian Army in terms of training and artillery, possessing the most up-to-date heavy weaponry, such as Russian T-72 Tanks.

The Division is made up of several brigades and regiments with headquarters at the main gateways of Damascus. The 555th Paratrooper Regiment led by Brigadier General Jamal Yunes, the 154th Regiment led by Brigadier General Jawdat Ibrahim Safi, the 40th Armored Brigade, and the 138th Infantry Brigade are all stationed in Muadamiyat. Zabadani, on the other hand, is home to the following battalions: military police, chemistry, engineering, monitoring, and training camp. Meanwhile, the 41st Armored Brigade is stationed in Yaafour and the 42nd Brigade is located in al-Sabboura. It should be noted here that all leaders of these brigades and regiments are Alawite. The 4th Armored Division’s forces’ most important responsibilities and security functions include:

- Nominating officers to be commissioned at security directorates according the criteria of possessing absolute loyalty to the regime and sectarian identity.

- Providing the Military and Air Force Colleges with a special list of names of people to be admitted. For the most part, this list primarily favors members of the 4th Armored Division and secondly serving members of other security agencies. This process is carried out in coordination with Branch 293 (Officers Affairs).

- The 4th Armored Division’s Security Office, which is headed by Brigadier General Ghassan Bilal (Maher al-Assad’s chief of staff), regularly coordinates with all other security directorates and directly examines any security incidents in the country’s provinces. The bureau also sends reports from its sources and officers to the main security agencies for them to take necessary action and notify the bureau as to what measures are being taken.

- The Security Office carries out investigations in all sensitive cases that directly threaten the cohesion of the security network or pose a risk to top regime officials.

- The division has a major role in the appointment of security branch chiefs, particularly those in Damascus.

To complete this summary, it should be noted that the 4th Armored Division is the only power whose responsibilities are limited to areas outside of Damascus. Its headquarters is located in as-Sabboura and it is not permitted to enter the capital, which stems from the concept of military sectors organizational structure with assigned responsibilities. Currently, Brigadier General Maher al-Assad leads the division and most of its officers are connected in some way to the RG, Ministry of Defense, Officers’ Affairs Bureau, and the Officers Branch.

Third: Tiger Forces (cross-military and security unit forces):

The “Tiger Forces” is a cross-agency special unit that intersects through military and security agencies. It is structured with three main elements: security and military core, volunteer and recruited Alawite manpower, and a customized administrative framework (Ministry of Defense) with an unrestricted authority to freely operate. This force has a wide margin of action and was formed to carry out a number of military and security duties, which include:

- Quickly intervening and responding to security changes and developments. The nature of these forces allows it to make decisions without the military establishment bureaucracy. Its forces are flexible, capable and have broad powers to act.

- Eliminating any risks or security threats against the Alawites and their spheres of influence in collaboration with military units and militias stationed nearby.

- Providing assurances to Alawites with the active presence of Alawite Tiger Forces, thus blocking any attempt or intention to mobilize any opposition within the sect.

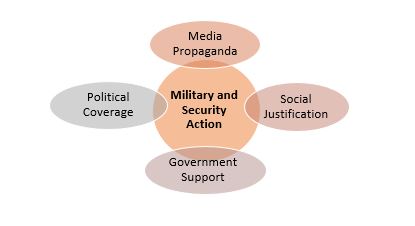

The Tiger Forces were formed as an alliance between AFID, the army, and the 4th Armored Division in 2013. They receive clear social support from most Alawites, funding from Rami Makhlouf’s Bustan Association, and coverage from state media outlets. Led by Brigadier General Suheil Al Hassan, the Tiger Forces enjoy a wide range of authorities and powers, including the ability to mobilize all state institutions – including civilian and military airports – to carry out their duties. Tiger forces have intervened in most areas of military conflict, including the Damascus Suburbs, Hama, Idlib, Homs, or the Latakia suburbs.

Auxiliary Agencies

These are a group of official state agencies already existing or recently formed for the purpose of blocking and curtailing the revolutionary movement’s work and supporting central agencies with updated and accurate information. The presence of these agencies is indicative of the transformation and deployment of executive branch institutions to serve the interests of the regime and its security agencies of infiltrating and weakening revolutionary forces and push it to change coarse away from its intended objectives. Some of these agencies and bodies include:

1. Communications Directorate (CD)

This directorate was formed in early 2011 after the outbreak of the Syrian uprising. It is closer to being a special task force comprised of: Landline and Cellular Communications Surveillance Branch (known as Branch 225 of the MID), Signals Branch 211, Technical Branch from the GID, and other technical branches in other directorates, in addition to al-Ghadeer Project that is under Iranian Management. All wiretapping and jamming projects stationed in different directorates were also merged into this directorate.

Its primary mission is to surveil all landline and cellular communications, internet, and television programs concerning topics on the revolutionary movement. The directorate also furnishes other security agencies with information collected from monitored communications, grants licenses for importing communication devices, and resolves conflicts between different directorates. It is also clearly noted that most recruits to this newly formed directorate are Alawite.

2. Security Units in the Ministry of Interior

Since the start of the uprising, all personnel and employees in the Ministry of Interior have been enlisted as informants for the PID. Furthermore, the ministry was tasked with the responsibility of helping and aiding some security branches by making arrests, conducting raids, and breaking up sit-ins by force of arms.

3. Political Party Services (Ba’ath Party)

These are divisions, sections, and branches of the Ba’ath Party spread throughout Syria and tasked with collecting security-related information and reports and providing it to the security directorates and the NSB. The regulated deployment of Ba’ath Party leaders and members in society helps the regime control all social activities and trends, particularly by granting the party complete powers of oversight, coordination, and surveillance over its auxiliary grassroots organizations, such as the Revolutionary Youth Union, the Students Union, the Workers’ Unions, and the like.

4. Security Officers Stationed with Military Units

In every military unit, from the corps, directorates, and divisions, to the smallest military unit, there is a security services officer who is stationed there to secretly surveil everything that occurs within his unit among his officer colleagues, his superiors, subordinates, and even their families and civilian acquaintances. The deployed officers submits reports pertaining to the simplest matters of everyday affairs to the MID or the AFID so that they, in turn, can investigate the issue further. Most of the time, the MID and AFID carry out their measures without verifying the credibility of the information in such reports.

5. National Defense Forces and People’s Committees

After the spark of the Syrian uprising, the Syrian regime, with direction from Iran and coordination with the RG, resorted to forming so-called National Defense Forces or People’s Committees, which transformed during the crisis from military bodies to auxiliary security institutions with their own special prisons and investigation commissions. These groups are essentially an army of mercenaries, crime lords, and unemployed citizens who have been hired to fight alongside the army and the security services. These individuals enrolled in the National Defense / People’s Committees not out of belief or faith, but to earn an illegal livelihood by carrying out theft, looting, blackmailing, and kidnapping. In addition to their work as informants for the army and security services, most of the time the information they provide is frivolous and sectarian, the goal of which is to prove their loyalty to Assad. These reports cannot be contested by other agencies and are rather taken as is and used as bases for random arrests and even murders.

Based on what has been previously mentioned, it is noticed that all of the Syrian state’s facilities and institutions during Assad’s rule are essentially at the disposal and control of the security services directorates that serve the President’s interests, other individual interests, or both at the same time.

Evaluation of Security Performance in Syria

The abuses and violations committed by Syrian security agencies have mounted on all levels: socially, economically and politically to the extent it has become a systematic and a well-known culture and practice expected by all security officers and agencies. These abuses can be categorized on five levels, all of which create a climate of suppression and corruption in society. These levels are listed below:

1. Working without a Plan

Security work has been bound by the objective of tracking “direct violations” and monitoring social and economic functions according to fluid standards not regulated by any specific legal foundation. Furthermore, upon examining duties and performance outcomes of security agencies it becomes clear there is no indication of any strategic plan on all levels:

- Planning: Upon observing the dynamics of security agencies’ work, there isn’t any linear course of action that it follows, except for the further empowerment of the regime. There is no official assessment of the real power possessed by directorates, but in fact there is an exaggeration of the tasks and responsibilities of those institutions. There is no objective needs assessment study that every directorate conducts according to industry standards relating to objectives and capacities. Security work is rather closely linked with militarizing the civilian population to turn them into security agents and informants, which in turn made these agencies a locus of concealed unemployment.

- Strategic Goals: Security services and networks are generally limited to fulfil two goals: The first is connected with the regime’s expectations and objectives mentioned above, while the second involves violent intervention in matters of societal security in order to control its parameters and not solve its problems. Several great strategic objectives are absent from current security practice, such as:

- Maintaining citizens’ identity and civic work.

- Promoting dialogue among civilian sectors.

- Economic security.

- Developing security work.

- Constructing a cohesive security sector.

- Human Resources: Training and development programs are limited to improving physical capabilities of personnel, criminology and technology education, as well as the indoctrination with the ideology of the Ba’ath Party (One leader and leading party). What the programs lack, however, are sessions that help boost the competency of security personnel either in the field of security sciences and its modern instruments and methods, or increase the level of education and familiarity with the legal system, or help build balanced relationships with the security sector.

- Budgets: Because of the absence of any clear supervisory or oversight authority, nowhere can anyone find the basis for the budget’s preparation and its sections and components as well as its calculation methods, and its consistency with the overall national economic conditions. This further reinforces assessment theories regarding these agencies on the lack of transparency, monitoring or evaluation mechanisms.

2. Legalizing Violations and Repression

Several “laws” have been coached into society’s public awareness that have been derived from the security services’ collective practice and culture, from its detainment procedures, to its investigations and accompanying inhumane methods used to extract confessions, and to its abuses of detainees. These practices were legalized and normalized, particularly after the power structure was consolidated during the events of the 1980s through practices that were engaged in by individuals and adopted by the security establishment as a whole. The most significant elements of this culture include:

- Giving security agencies open-ended authority to apprehend, search, investigate, interrogate, detain, wiretap, and arrest under martial law any citizen without receiving an approval by the judicial authority. In other words, the agencies’ power is not restricted when carrying out these operations and no branch or department has to abide by the set legal time limit when holding or detaining citizens. Accordingly, a detainee can be imprisoned for several months or years without ever appearing before a judge.

- Depriving citizens their right to request a ruling from the judiciary on the legitimacy of an arrest, blocking the right to defend detainees or appoint a lawyer during their detainment by the security services, barring detainees from knowing their fate, the charges against them, and not allowing them visitations or even knowing why they were arrested.

- Security agencies regularly exceed the legal authorities and jurisdiction stipulated by existing laws that established those agencies, and interfere in areas out of its authority of jurisdiction. An example is there interference of Military Security Directorate in the lives of civilians in matters not related to military affairs, as well as with regards to opposition movements and parties. Security agencies pressure all pro-regime political parties as well as neutral parties, and target members of opposition parties.

- Security agencies often submit requests to wiretap communications of any person or entity without abiding by legal boundaries. Any agency or directorate can wiretap any person, even if the reason is personal. Secret surveillance operations of suspects, and the video and sound clips resulting from such action, could be leaked or accessed by dishonest individuals within the security services.

- The absence of effective oversight of security officials’ work leads to major abuses being committed often resulting in the death of detainees, rape incidents, and the killing of detainees without any inquiry as to the reasons for such incidents.

- Security agencies arrest thousands of Syrians for unknown reasons, the majority of which are never handed over to the judiciary for many months. Instead they are handed over to military and counter-terrorism courts. Furthermore, there are thousands of detainees who died under torture in regime prisons.

3. Instituting Sectarianism within the Security Structures

Security agencies’ heads and commissioned officers are appointed on a sectarian and confessional basis so as to preserve power within those groups. For example, the majority of personnel and officers in AFID are Alawite, and the majority of officers and key personnel in critical departments and divisions of other security directorates are Alawites. On a secondary level, other minorities are also disproportionately appointed to key influential positions. Loyalty, rather than competence, remains the main basis for appointments. There are nonetheless sensitive positions within the security services that must remain dominated by Alawites, such as Branch 251, which is the internal branch in the GID. This also goes for the MID’s Branch 293 and the SID’s Investigation Branch. In fact, it has been impossible for any non-Alawite to head any of these branches.

4. Intentional Lack of Coordination across Agencies

The institutionalized practices of non-coordination across agencies resulted in officers and agents abusing their powers by exploiting private and public state institutions, facilities and resources. This lead to the incapacity of societal oversight, the restriction of any public engagement, and the forced nonparticipation of citizens. On the other hand, the decentralized nature of security related decision making processes such as investigating and detaining, makes citizens liable for questioning on the same matter at multiple security branches, effectively crippling any societal movement with a prevailing security culture.

5. Exploiting Authority and Spreading Corruption

The constant interference of security agencies in the work of the police force, anti-drug units, and all other institutions including civilian and service providing bureaus as well as the judiciary has contributed to the wide spread phenomenon of “blatant encroachment” by these agencies on the power and authority of both governmental and private institutions for personal interests not related to intelligence work. This has also contributed to the propagation of practices that result in personal gains and material benefits while turning a blind eye to administrative, professional, and even penal crimes. At the same time, this conduct has deepened the culture of favoritism, malicious informant reporting, and led security personnel to exploit their authority that is sanctioned by the regime, namely to blackmail businessmen, manufacturers, and investors. All of these actions stem from a lack of an oversight authority over security personnel and restricting any disciplinary actions to internal procedures dependent on the discretion of their superior officers. It should also be noted that procurement contracts for the purchase of technical equipment needed by security agencies is done secretly without government supervision through deals between officers and security agents with domestic or foreign entities. This makes corruption and embezzlement ever present and unavoidable, while cases of security information leaks for the purpose of blackmail and direct material benefit have increased due to lack of respect for confidentiality within security service departments.

II. The Need for Structural and Functional Change

Causes and Results of Deficiency

Over the past few decades, the Syrian security services have been the “big stick” in the hand of the regime and have been used, from the beginning, to deepen its authority, dominate the country, and eliminate its opponents. They have earned the terrifying reputation as the first guarantors of government stability. As a result of the role they have played in strengthening and protecting the President rule, they have gone on to significantly expand their powers by interfering in all aspects of social, economic, political, and religious life. This also has spread corruption, favoritism, and illegitimate wealth accumulation throughout the security services’ different detachments, turning them into a distinguished social class apart from the rest of society. Consequently, what makes the security services deficient is their prevailing work philosophy and security doctrine, which serves the needs of the ruler more than those of the ruled.

There are two main sources of the security service’s failings and aberrations that can be identified. The first source lies in their complex and deeply invasive structure, which has helped curb the societal activities and limited its ability to advance and develop. The second source pertains to their fluid and unrestricted functioning mechanisms, except when it pertains to the duty of protecting and preserving the regime stability.

Other reasons behind the deviation of the security agencies in Syria from fulfilling their objectives, includes the following:

- The security agencies corrupt doctrine, which stems from absolute loyalty to the head of the regime and the resulting poor professional performance.

- The serious overlap in the security agencies responsibilities and mandate often leads to conflicting practices and decisions in spite of there being a foundation for determining the competencies and powers of each apparatus and the tasks assigned to them.

- When facing other security services, the power and influence of a given security body is linked to the power and influence of its chief leader.

- The high level of competitiveness between security agencies and branches, the antipathy between them, and the race on surveilling one another in the service of the President.

- Rampant corruption in security agencies, particularly after they were tasked with countering smuggling operations in border areas, and its interferences in municipal affairs so as to block construction on farmland. This has led many to be directly involved in smuggling operations and dominating the public sector with regards to employment and appointments.

- The massive build-up of security agencies’ assets in Syria, particularly by the MID, in a way that does not correspond to the scope and volume of responsibilities assigned.